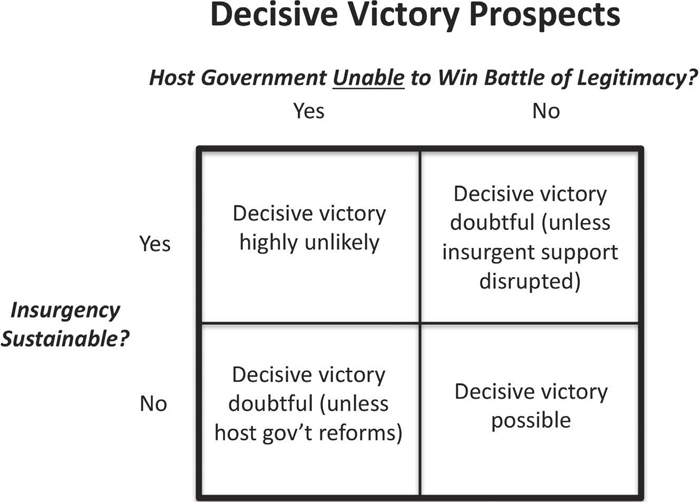

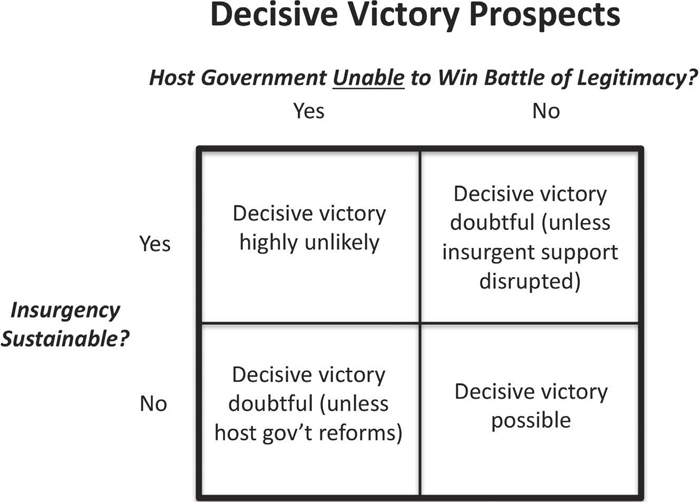

Figure 1. Critical Factors Framework

Among the many different concepts that are used to classify war and warfare, the distinction between conventional and irregular wars is one of the most basic. Conventional wars are clashes between uniformed militaries, fighting largely under the same rules, until one side wins or stalemate ensues. Of the major wars fought by the United States before September 11, 2001, nearly all of them pitted uniformed American soldiers against uniformed adversaries—notable exceptions being the American Revolution (many irregular forces fought for independence outside the control of the Continental Army), the Philippine Insurrection (1899–1902), and the Vietnam War (1964–1975).

Irregular war, by contrast, is a violent struggle among state and nonstate actors to win political legitimacy.1 The latter can be an insurgent or militant group that seeks to win the support of the population to its cause. As a nonstate actor, it often operates in and among the population; many of its members simply operate from their homes and wear everyday civilian attire, making them difficult to distinguish from civilians. The group relies on the population for recruitment, supplies, and protection. Such groups often employ guerrilla tactics to strike targets at times and places of their choosing, after which they disappear into the local population. Their goal is to wear down the conventional force.

These wars are often fought in the developing world, where local populations have major grievances against the ruling elite. Historically, irregular wars occur more often than conventional wars. These are so-called “away games” for the United States—wars in other countries—in which no existential threat exists. The comparatively small stakes involved in irregular wars make it natural for the United States to focus on conventional wars. This bias is part of what can be termed the conventional war paradigm.

The US national security establishment is organized intellectually and bureaucratically around the ability to wage conventional war. This has had major implications on how the United States develops strategy. Critically, it has shaped a mindset within the US national security establishment that sets zero-sum decisive victory as the default option for success. Once decisive victory was deemed no longer possible in the wars in Vietnam, Afghanistan, and Iraq, the United States struggled to develop a coherent alternative.

Can a strategy that aims for or implicitly assumes zero-sum decisive victory place an intervening power at higher risk of quagmire? Clausewitz’s statement above suggests this is possible.2 Competitive interaction creates complexity and uncertainty. These factors make war unpredictable and increase the risks that the intervening power will make strategy errors that undermine the likelihood of success.

A huge imbalance in the correlation of military forces, for instance, could lead an intervening power to place excessive faith in military force to achieve decisive victory. Insurgents recognize these imbalances and seek to minimize opponent strengths while exploiting inherent vulnerabilities. Thus, insurgent forces tend to wage wars of exhaustion that avoid decisive battles. They focus on population control and support. They use violence both to wear down stronger opponents and to communicate their own relevance and staying power.3

The military contest tends to gain the most attention, but the political, diplomatic, and economic dimensions of the conflict tend to be more decisive.4 An intervening power that prioritizes the military effort heightens the risk of making self-induced errors. The mixed record of counterinsurgencies, even those with external support from sophisticated western powers, suggests that strategies based primarily upon military factors can increase the likelihood of failure.5

Political scientist Chris Paul and his colleagues at RAND were fascinated by this paradox and sought to determine the key to successful counterinsurgency. They analyzed 71 insurgencies since 1944 for common themes, approaches, and practices that led to the counterinsurgents’ success. They classify 42 as insurgent wins (a 59 percent success rate), and tally 29 for the counterinsurgent (a 41 percent success rate).6 Their study led them to examine the salience of 24 counterinsurgency approaches, and then to arrive at a scorecard of 15 good and 11 bad practices.7

Each counterinsurgent win, they point out, had two critical factors. First, successful counterinsurgents were able to reduce significantly the tangible support for insurgency. The keys were external sanctuary and indigenous support. Second, the host nation had to be committed to winning the battle of legitimacy in contested and insurgent-controlled areas. The absence of one factor or the other consistently led to a counterinsurgent loss.8

Tangible support is the ability of the insurgency to recruit manpower, obtain matériel, sustain financing, gather critical intelligence, and have access to sanctuary.9 The ability of the insurgents to sustain such tangible support almost perfectly correlates to the outcome of the war. Tangible support is not necessarily the same as popular support. A counterinsurgent can have the support of the majority but still not win if the insurgency sustains enough tangible support to pose a material threat to the government.10 These findings are reinforced in Jason Lyall’s analysis of 286 insurgencies: material support was one of the top three determinants of the war’s length and outcome.11 If the counterinsurgents failed to reduce the tangible support available to the insurgency significantly, the result was a loss in every case. In only two cases did the counterinsurgent disrupt tangible support and still lose.12

The second critical factor is the commitment of the host nation to win the battle of legitimacy. Perverse practices that demonstrate failure of resolve include maximizing personal wealth and power at the expense of the state and citizenry, protecting unfair divisions of power and support, extending the conflict to bilk external supporters, and/or avoiding combat.13 Governments motivated by such perverse incentives become predatory and exclusionary; in so being, they alienate significant portions of the population and create grievances that feed into the tangible support of the insurgency. Put succinctly, the problems articulated above undermine the legitimacy of the government.

Host nation governments experiencing such problems become unable to regain and retain support in contested and insurgent-controlled areas. Paul and his colleagues found 17 cases in which the host nation lacked commitment to winning the battle of legitimacy.14 The host nation lost each time. In 26 of 28 wins, the host nation government met the critical test of commitment in the early phases of the conflict.15 This suggests that highly damaging predatory and exclusionary practices become entrenched over time, making reform more difficult. At some point, reversing such problems may become impractical.

External intervention seems unable to overcome unfavorable critical factors. In 28 cases, an external actor intervened to support a host nation government battling an insurgency. Externally supported counterinsurgents won no more often than wholly indigenous counterinsurgents.16 Not a single intervention by a great power prevailed if one or both critical factors remained unfavorable, as seen in the cases of Vietnam (1960–1975), Afghanistan (1978–1992; 2001–2016), and Iraq (2003–2016).17

Figure 1. Critical Factors Framework

The presence of an unfavorable critical factor did not exclude the possibility of decisive victory. In some cases, the counterinsurgent managed to change the unfavorable variable. The insurgent’s tangible support was sufficiently disrupted in Sierra Leone (1991–2002), Uganda (1986–2000), and Turkey against the PKK (1984–1999).18 The governments of Senegal (1982–2002), Peru (1980–1992), and Angola (1975–2002) enacted a sufficient number of reforms to succeed.19

In sum, two critical factors appear to be salient: is the insurgency sustainable and is the host government unable to win the battle of legitimacy in contested and insurgent-controlled areas? Figure 1 above illustrates the likely outcomes against those factors. If both answers are yes, then the probability of the host nation achieving a decisive victory—even with external intervention—is highly unlikely.

For an external power, this table can be highly useful in determining whether or not to intervene on behalf of a host nation. If both factors are negative, it might be wiser for the external power to remain uninvolved, or to devise a strategy that aims for a negotiated outcome or transition.

On the other hand, if the insurgency is not sustainable (i.e., tangible support is effectively disrupted or nonexistent) and the government can take and retain contested and insurgent-controlled areas, the chances for a decisive victory improve significantly. External support could expedite the host nation’s victory.

Decisive victory, of course, is not the only way to succeed. Insurgencies can end in a negotiated settlement—that is, a “mixed” outcome in which neither side forces the other to surrender but one does relatively better in attaining its aims. Paul and his colleagues code that actor as the winner. The reality does not need to be so binary; multiple actors can be considered successful if their aims are attained durably. This is particularly true for an intervening power that probably has less at stake than the local actors. Theoretically, a negotiated settlement in which the host nation government remains intact, the insurgency becomes part of the polity and is no longer under military threat from the intervening power, and the government and insurgency agree to measures that protect the intervening power’s interests could be viewed as a win-win-win outcome.

An intervening power could also transition security responsibility for an ongoing conflict to the host nation, and then proceed to withdraw. This is premised on the “crossover” point: as the foreign counterinsurgent degrades the insurgency and builds the capacity of the host nation’s security forces, the latter will become capable of defeating the insurgency. Once this threshold is reached, the foreign force can withdraw knowing that the partnering host nation is capable of succeeding on its own, or with minimal support.

Paul et al. identify six cases in which an intervening power adopted the transition method; out of these six, the government won only twice.20 While this is too small a sample size to draw inference, as the authors themselves recognize, it is nevertheless possible to articulate some hypotheses.

The importance of the host government’s ability to win the battle of legitimacy suggests that a transition strategy should place greater weight on factors that improve or prevent damage to legitimacy rather than on fighting the insurgency. Otherwise, the theoretical crossover point might never occur. As discussed in more detail later, a strategy that initially seeks a decisive victory but then changes to transition may require that the intervening force shifts its strategic and operational priorities.

The critical factors above are important characteristics of a conflict. Policymakers and strategists should consider them when determining which war termination outcomes are feasible. If both critical factors are unfavorable, the external power should avoid seeking decisive victory unless there are compelling reasons to believe the factors can be reversed. Otherwise, aiming for a different outcome or declining intervention altogether are the better choices.

While weighing the likelihood of success, the external power should also consider the element of time. The average (mean) duration of the 71 insurgencies since 1944 was 128 months (10.7 years), while the median duration was 118 months, or 9.8 years. Counterinsurgent wins tend to take longer than losses (132 months versus 72 months).21 The potential costs in blood, treasure, and time should factor in strategic decision-making.

These calculations should also inform interventions that seek to replace an existing regime with a new, friendlier one. In such cases, the intervening power must ensure that the two factors do not become unfavorable in the aftermath. If a sustainable insurgency develops or the host nation becomes predatory and exclusionary, there is a low likelihood that regime change will result in a decisive victory.

The introductory chapters have outlined a taxonomy of successful war termination outcomes for irregular war interventions, how these could factor in the policy and strategy processes, and the conditions under which decisive victory is possible.

The US government, however, has no organized way of differentiating successful war termination outcomes and their role in policy and strategy considerations. This is creating three systemic errors that have heightened the risk of major irregular war interventions becoming quagmires. First, the presumption that success requires decisive victory is restricting policy options, placing undue emphasis on the use of military force, and inducing military-centric strategies that have low probabilities of success. Second, the US government has difficulty modifying losing or ineffective strategies due to cognitive obstacles, political and bureaucratic frictions, and entrapment by the host nation. Third, as the war drags on, public support wanes, and the administration gives up on decisive victory, the United States forfeits critical leverage in announcing a withdrawal and a desire to seek negotiations or transition. The insurgency calculates that its leverage will be higher after the US military leaves and thus resists negotiating an end to the conflict. The host nation government, meanwhile, has become so dependent upon US financial and military support that transition becomes unrealistic. The United States thus becomes trapped in conflicts longer than may be necessary. The following case studies will illustrate the consequences of these errors.