P&G also had the brilliant idea of presenting Crisco to the Jewish housewife as a kosher food, one that behaved like butter but could be used with meats. Because it made kosher cooking easier, Jews adopted Crisco and margarine—imitation lard and imitation butter—more quickly than other groups, with unforeseen consequences.

Procter & Gamble’s strategy was obvious: demonize the competition, but do it in a way that would appeal to the thrifty turn-of-the century housewife, eager to be modern and clean.†

Crisco was not the first manufactured fat presented as suitable for human consumption. In 1869, Emperor Napoleon III of France offered a prize to anyone who could make a satisfactory alternative for butter, “suitable for use by the armed forces and the lower classes.” French chemist Hippolyte Mège-Mouriès invented a substance he called oleomargarine, later shortened to “margarine.” The principal raw material in the original formulation was beef fat, but in 1871, Henry W. Bradley of Binghamton, New York, patented a process for creating margarine that combined vegetable oils (primarily cottonseed oil) with animal fats. With cheaper ingredients, the margarine business promised great profits.

In Life on the Mississippi, published in 1883, Mark Twain recalls a conversation he overhears between a New Orleans cottonseed oil purveyor and a Cincinnati margarine drummer. New Orleans boasts of selling deodorized cottonseed oil as olive oil in bottles with European labels. “We turn out the whole thing—clean from the word go—in our factory in New Orleans… We are doing a ripping trade, too.” Cincinnati reports that his factories are turning out oleomargarine by the thousands of tons, an imitation that “you can’t tell from butter.” He gloats at the thought of market domination. “You are going to see the day, pretty soon, when you won’t find an ounce of butter to bless yourself with, in any hotel in the Mississippi and Ohio Valleys, outside of the biggest cities… And we can sell it so dirt cheap that the whole country has got to take it… butter don’t stand any show—there ain’t any chance for competition. Butter’s had its day—and from this out, butter goes to the wall. There’s more money in oleomargarine than—why, you can’t imagine the business we do.”2

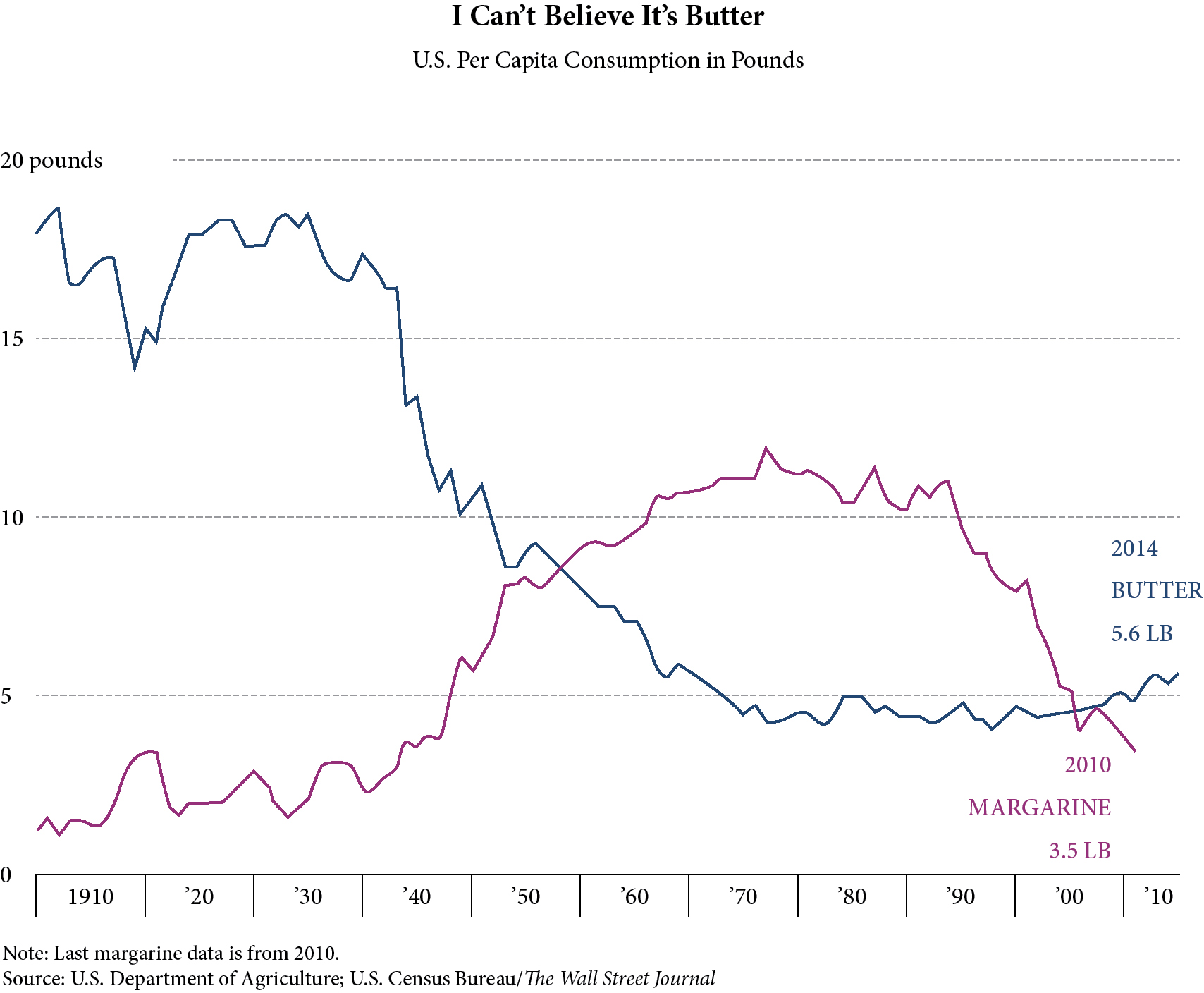

Early ads for margarine had little copy and made no claims; instead, pictures of healthy babies and pretty girls conveyed wholesome goodness. The best they could do was imply equivalence at a lower price. And there was much resistance. People still preferred butter—in part because they could make it in their kitchens. Butter consumption in 1900 was about eighteen pounds per person per year,3 or about five teaspoons per day, and probably a lot higher among farm families. Early visitors to America, such as de Tocqueville, noted that Americans were a butter-eating nation, that they put butter in or on everything including soups, sauces, meat, vegetables, porridge and puddings.4 Early cookbooks included recipes for salad dressing based on melted butter.5 People cooked in lard, bacon fat and beef dripping because that was what they had.

In the early 1900s, the chief medical concern was poor health in children—infectious disease, rickets, anemia and growth problems—problems rightly attributed to poor nutrition. On the basis of research carried out in the 1920s and 1930s, the British Medical Association recommended that all British people consume 80 percent more milk, 55 percent more eggs, 40 percent more butter and 30 percent more meat. The British government introduced free school milk—that would be full-fat milk—and encouraged the consumption of more animal foods, especially eggs.

Following this policy, childhood deaths from diphtheria, measles, scarlet fever and whooping cough fell dramatically—well before the advent of antibiotics and vaccinations. Rickets and other childhood afflictions became rare. These recommendations continued into the Second World War, when all British children received a ration of eggs, cod liver oil and orange juice. During these years, the life expectancy in England climbed to sixty years in 1930 and seventy years in 1960.6

In America as well, most American doctors recognized the value of milk, eggs, butter, liver, cod liver oil and meat in the diet. Doctors told mothers to prepare liver once a week in order to prevent anemia, and housewives judged the quality of milk by the amount of cream it contained. The American and His Food, published in 1940, listed milk, cheese, eggs, liver, fatty fish, green vegetables, raw fruits, butter and cod liver oil as “highly protective foods” and legumes, cereals, bread, nuts, sugar, jam, honey, margarine, olive oil and other vegetable oils as “nonprotective foods.”7

The Story of Crisco notwithstanding, advertisers found it difficult to make claims based on science or health benefits in this climate of common sense. They relied on price as the deciding factor. And then an innocent molecule called cholesterol entered the public consciousness. Cholesterol conveniently occurs only in animal foods, especially in saturated animal fats like lard and butter.

THE THEORY THAT CHOLESTEROL CAUSES heart disease dates from 1779 when Caleb Parry, an English physician, published his discovery that obstructed coronary arteries caused angina pectoris or chest pain.8 In 1910 the German chemist Adolf Windaus reported that these lesions contained six times as much cholesterol as a normal arterial wall.9*

In 1912, just as Crisco was coming to market, Nikolai N. Anichkov, a Russian scientist, induced atherosclerosis—obstructions in the arteries—by feeding foods like egg yolks and purified cholesterol to vegetarian rabbits. One year later he announced the discovery that cholesterol was “the primary factor” in initiating atherosclerosis.10 (One minor detail: Anichkov fed his rabbits cholesterol dissolved in vegetable oil, not saturated animal fats. Subsequently researchers routinely used vegetable oils as a base for cholesterol to induce atherosclerosis in animals.11)

But the fabulous marketing opportunity that awaited the makers of margarine, shortening and industrial vegetable oils did not materialize until after the Second World War. In the 1950s, a new health problem emerged—not rickets or other obvious manifestations of malnutrition—but heart disease, especially sudden death from myocardial infarction or heart attack.

While turn-of-the-century mortality statistics are unreliable, they consistently indicate the fact that heart disease caused no more than 10 percent of all deaths, considerably less than infectious diseases such as pneumonia and tuberculosis. Heart disease in 1900 usually manifested as gradual heart failure after a serious case of typhoid fever, not as sudden death by heart attack. The first recorded U.S. case of myocardial infarction (MI)—the scientific term for heart attack—occurred in 192012; three thousand deaths from MI occurred in 1930. By 1960, coronary heart disease (CHD) was the leading source of mortality in the United States, causing more than three hundred thousand deaths annually. The greatest increase came under the rubric of myocardial infarction.13 What was causing this new epidemic?*

In 1950 an American doctor, John Gofman, later known for his work on the dangers of x-rays and atomic radiation, resurrected the hypothesis that blood cholesterol was to blame. He noted, “For reasons still unknown, coronary heart disease suddenly took off during the 1920s throughout the industrialised world. By the 1940s it was becoming the major cause of premature death. And nobody knew why.”14

Nobody knew why, but it was easy to theorize. One explanation was the decrease in infectious disease following the decline of the horse as a means of transport and the removal of horse manure from city streets, the installation of more sanitary water supplies, and the advent of better housing. These measures allowed more people to live to adulthood and thus made them more likely to experience a heart attack.

The other theory focused on a dietary change. Since the early part of the century, when the Department of Agriculture began tracking food “disappearance” data—or the amount of various foods going into the food supply—a number of researchers had noticed a change in the kind of fats Americans were eating. Butter consumption was declining while the use of vegetable oils, especially oils hardened to resemble butter or lard, was increasing—dramatically increasing. By 1950 butter consumption had dropped from eighteen pounds per person per year to just over ten. Margarine filled in the gap, rising from about two pounds per person at the turn of the century to about eight. Lard consumption plummeted from fifteen pounds per person per year to about three. Consumption of vegetable shortening—used in the home and in crackers and baked goods—remained relatively steady at about twelve pounds per person per year (up from zero in 1912), but consumption of liquid vegetable oil more than tripled—from just under three pounds per person per year to more than ten.15 Sugar consumption was up as well, from less than ten pounds per year in 1820 to almost eighty pounds in 1950.16 The statistics pointed to one obvious conclusion—to combat the rise in heart attacks, Americans should return to eating the traditional foods that nourished their ancestors, including meat, eggs, butter and cheese, and avoid the newfangled foods based on industrial oils (and sugar) that were flooding the grocers’ shelves.

Even as the evidence pointed to the dietary shift toward oils and sugar as a cause, researchers continued to align themselves behind the idea that cholesterol was to blame for the epidemic. In 1954 a young researcher from Russia named David Kritchevsky repeated Anichkov’s rabbit experiment. Kritchevsky agreed with the original findings: cholesterol added to vegetarian rabbit chow caused the formation of atheromas. In the same year, Kritchevsky published a paper describing the beneficial effects of cholesterol-free polyunsaturated fatty acids—found in liquid vegetable oils—for lowering cholesterol.17

Another early researcher was Dr. Edward H. Ahrens. For decades, Ahrens conducted research on blood cholesterol levels to determine whether a dietary change could prevent atherosclerosis. His research showed that the substitution of liquid vegetable oils for solid animal fats could reduce levels of the villainous cholesterol molecule, at least for the duration of short-term human experiments. The discovery did not show that liquid oils could lower the rate of heart disease, but many used it as justification for urging a switch from saturated animal fats to liquid polyunsaturated oils.*

Much credit for popularizing the cholesterol theory of heart disease goes to the persuasive and strong-willed Ancel Keys, a University of Minnesota researcher. His various epidemiological studies made him the most famous scientist in the nutrition world as he championed the idea that saturated fats raise cholesterol and therefore cause heart attacks. It was Keys, more than any other, who promoted the idea of the Mediterranean diet as low in fat and cholesterol, and rich in vegetables and beans. These conclusions came from dietary surveys carried out in Italy, Greece and middle Europe in the early 1950s, when these populations were still recovering from the wartime shortages—and they were carried out during Lent!18 The idea that the Italian diet—rich in cured pork products, cheese and meat—is low in saturated fat contradicts all the evidence. Keys fancied himself a gourmet but does not seem to have enjoyed linguine Alfredo or pepperoni pizza during frequent sojourns in Italy.†

Another member of this rogue’s gallery was Jeremiah Stamler, MD, the doctor credited with introducing the term “risk factors” into the field of cardiology. Listed as an author on over four hundred papers, starting in 1948 with a study entitled, “The effect of a low fat diet on the spontaneously occurring arteriosclerosis of the chicken,”19 and continuing to 2015, Stamler insists even today that dietary cholesterol raises serum cholesterol, a premise that has faded with overwhelming findings to the contrary. Even during the heyday of cholesterol research, Stamler was highly selective in the studies he cited to justify his assertions. In a 1988 paper Stamler maintained that dietary cholesterol “has a substantial impact on blood cholesterol.” As proof, he cited seven studies, and ignored many others. Two of these were irrelevant liquid diet studies and the remaining five indicated trivial effects of dietary cholesterol.20 When the International Atherosclerosis Project found no relationship between diet and degree of arterial obstruction or proneness to heart disease, he continued to insist that “a highly significant correlation was found between intake of fat and severe atherosclerosis at autopsy.”21 In 1963, sponsored by Mazola Corn Oil and Mazola Margarine, Stamler coauthored a booklet called Your Heart Has Nine Lives, urging people to substitute vegetable oils for butter and other “artery-clogging” saturated fats.22

Dr. Frederick Stare, head of Harvard University’s Nutrition Department for over forty years, added to the confusion surrounding cholesterol and saturated fat. He wrote a popular syndicated column that promoted the consumption of polyunsaturated oils and urged readers to reduce consumption of saturated fat and dietary cholesterol by avoiding eggs, meat and butter. In one 1969 column he stated, “To my knowledge, I’ve never heard of too much polyunsaturated fat for man.”

He knew how to play fast and loose with the science: in a promotional piece specifically for Procter & Gamble’s Puritan Oil, he cited two experiment and one clinical trial as showing that high blood cholesterol is associated with coronary heart disease (CHD).23 However, neither experiments had anything to do with CHD, and the clinical trial did not find that reducing blood cholesterol had any effect on CHD events. Nor was he bothered by any conscience for consistency. In 1986, he published a letter to the editor in FDA Consumer claiming, “far too much emphasis to the hazards of saturated fat and dietary cholesterol and not enough to the hazard of too many calories is given by the magazine.” In a 1989 letter to the editor of the Journal of the American Medical Association he asserted that “The [blood] cholesterol factor is of minor importance as a risk factor in cardiovascular disease.”*24

Irving Page served as president of the American Heart Association (1956–57) and in 1961 coauthored—with Ancel Keys, Jeremiah Stamler and Frederick Stare—the American Heart Association’s revised dietary guidelines. The new guidelines recommended that Americans reduce the consumption of total fats and cholesterol and increase the amount of polyunsaturated fats, this despite the fact that Page and Stare had previously published papers showing that the increase in coronary heart disease mirrored the rise in consumption of vegetable oils.25 Only a few years earlier, Keys had proposed the theory that the increasing use of hydrogenated vegetable oils might actually be the underlying cause of heart disease.26

The 1968 AHA statement went further and quantified just how much fat and cholesterol people should be eating, with recommendations to limit cholesterol to 300 milligrams per day (typical diets contain 600–800 milligrams per day) and total fat to 30–35 percent of calories, comprised equally of saturated, polyunsaturated and monounsaturated fatty acids (typical diets contain 40–80 percent of calories as fat). These recommendations remain even to the present, enshrined in the USDA Dietary Guidelines.

It was these early researchers who formulated the “diet-heart theory” (that dietary choices can affect cholesterol levels in the blood) and the “lipid hypothesis” (that blood cholesterol levels determine proneness to heart disease). The appeal to the industrial oil industry was obvious—seed oils, as opposed to animal fats like butter, tallow and lard—contain no cholesterol and very little saturated fat. If feeding polyunsaturated oils from vegetable sources lowered serum cholesterol in humans, at least temporarily, and feeding vegetarian animals cholesterol caused plaque buildup in their arteries—oils were the clear solution! Using this shaky science, researchers put forward the idea that Americans could avoid heart disease by reducing animal products in their diet and lowering their cholesterol by substituting polyunsaturated oils. And this line of argument just happened to prove a boon to those who produced products that could substitute for butter, cream, eggs and lard.

Procter & Gamble was the first in the industry to capitalize on this opportunity brought forth by this new theory of heart disease prevention. In 1948, P&G made the American Heart Association (AHA) the beneficiary of their popular “Walking Man” radio contest, which the company sponsored. The show raised almost two million dollars for the organization and transformed it (according to the AHA’s official history) from a small, underfunded professional society into the powerhouse it remains today.27 Originally founded in 1924 to study the effects of diseases like rheumatic fever on the heart, the organization morphed into the most influential advocate for a diet low in cholesterol and saturated fat. Their advice, even today, is unwaveringly fat-phobic: avoid butter, cream, ice cream, egg yolks and whole milk in favor of industrial seed oils, soft margarines, skinless chicken breasts, lean meat, egg whites and low-fat salad dressings.28 The AHA remains the main force in the war on animal fats—with no concern about the consequences.

IN THE YEARS THAT FOLLOWED, a number of population studies demonstrated that the animal model—especially one derived from vegetarian animals like rabbits—was not a valid approach for studying the problem of heart disease in human omnivores. As early as 1936, pathologists K. E. Lande and W. M. Sperry at Harvard University looked at cholesterol levels and degree of coronary artery occlusion in individuals who had died a sudden death. They found no correlation; there were individuals with low cholesterol and a high degree of occlusion and individuals with high cholesterol and a low degree of occlusion.29

A much publicized 1955 report on artery plaques in American soldiers killed during the Korean War showed high levels of atherosclerosis, but another report—one that did not make it to the front page of the New York Times—found that Japanese natives had almost as much pathogenic plaque—65 percent versus 75 percent—even though the Japanese diet at the time was lower in animal products and fat.30 A 1957 study of the largely vegetarian Bantu found that they had as much atheroma as other races from South Africa who ate more meat.31 A 1958 report noted that Jamaican blacks showed a degree of atherosclerosis comparable to that found in the United States, although they suffered from lower rates of heart disease.32 A 1960 report noted that the severity of atherosclerotic lesions in Japan approached that of the United States.33 The 1968 International Atherosclerosis Project, in which over twenty-two thousand corpses in fourteen nations were cut open and examined for plaques in the arteries, showed the same degree of atheroma in all parts of the world—in populations that consumed large amounts of fatty animal products and those that were largely vegetarian, and in populations that suffered from a great deal of heart disease and in populations that had very little or none at all.34 These studies pointed to the likelihood that the thickening of the arterial walls is a natural, unavoidable process. The diet-heart theory and the lipid hypothesis put forward by American researchers did not hold up to these population studies, nor did it explain the tendency to fatal clots associated with myocardial infarction.

But the lipid hypothesis had already gained enough momentum to keep it rolling, in spite of the contradictory studies that were showing up in the scientific literature. In 1957, Dr. Norman Jolliffe, director of the Nutrition Bureau of the New York Health Department, initiated the Anti-Coronary Club, in which a group of businessmen, ranging in age from forty to fifty-nine years, were placed on the Prudent Diet. Club members used corn oil and margarine instead of butter, cold breakfast cereals instead of eggs, and chicken and fish instead of beef. A control group of men the same age ate eggs for breakfast and had meat three times a day. Jolliffe, an overweight diabetic confined to a wheelchair, was confident that the Prudent Diet would save lives, including his own.

That same year, 1957, the food industry initiated advertising campaigns that touted the health benefits of products low in fat or made with vegetable oils. A typical ad read: “Wheaties may help you live longer.” Wesson recommended its cooking oil “for your heart’s sake,” and a Journal of the American Medical Association ad described Wesson oil as a “cholesterol depressant.” Mazola advertisements assured the public that “science finds corn oil important to your health.” Medical journal ads recommended Fleischmann’s Unsalted Margarine for patients with high blood pressure. Such advertising continued unabated through the 1960s and 1970s. A 1970 ad for Fleischmann’s “Golden Corn Oil” Margarine, appearing in the Journal of the American Medical Association, showed a heart wrapped in a Fleischmann’s Margarine wrapper with the headline, “Eat to your heart’s content.” The text sauntered along in the same jaunty, pseudoscientific style as The Story of Crisco. “According to latest medical opinion, a low-saturated-fat, low-cholesterol diet is still one of the best ways to a man’s heart. Such diets invariably include a vegetable oil margarine—like Fleischmann’s.”

The vegetable oil industry soon discovered a foolproof advertising technique: get the guys in white coats to do your advertising for you. Dr. Frederick Stare, head of Harvard University’s Nutrition Department, came first, promoting vegetable oils in his syndicated column. Later, Dr. William Castelli, director of the Framingham Study, provided an endorsement for Procter & Gamble’s Puritan Oil; Dr. Frederick Stare also promoted Puritan. Dr. Antonio Gotto, Jr., former president of the American Heart Association, sent a letter promoting Puritan Oil to practicing physicians—printed on letterhead from the De Bakey Heart Center at Baylor College of Medicine.35 The irony of Gotto’s letter is that De Bakey, the famous heart surgeon, coauthored a 1964 study involving seventeen hundred patients, which also showed no definite correlation between serum cholesterol levels and the nature and extent of coronary artery disease.36 In other words, those with low cholesterol levels were just as likely to have blocked arteries as those with high cholesterol levels. But while studies like De Bakey’s moldered in the basements of university libraries, the vegetable oil campaign took on increased bravado and audacity.