The American Medical Association at first opposed the commercialization of the diet-heart theory and warned that “the anti-fat, anti-cholesterol fad is not just foolish and futile… it also carries some risk.”37 The American Heart Association (AHA), however, was committed.

Your Heart Has Nine Lives—a little self-help book by Stamler and sponsored by the makers of Mazola Corn Oil and Mazola Margarine—showed up in the 1960s, advocating the substitution of vegetable oils for butter and other so-called “artery clogging” saturated fats. Stamler did not believe that lack of evidence should deter Americans from changing their eating habits. The evidence, he stated, “was compelling enough to call for altering some habits even before the final proof is nailed down… the definitive proof that middle-aged men who reduce their blood cholesterol will actually have far fewer heart attacks waits upon diet studies now in progress.” His version of the Prudent Diet called for substituting low-fat milk products such as skim milk and low-fat cheese for cream, butter and whole cheese, reducing egg consumption, and cutting the fat off red meats. Heart disease, he lectured, was a disease of rich countries, striking rich people who ate rich food, including “hard” fats like butter.38

It was in 1966 that the results of Dr. Jolliffe’s Anti-Coronary Club experiment were published in the Journal of the American Medical Association.39 Those on the Prudent Diet of corn oil, margarine, fish, chicken and cold cereal had an average serum cholesterol of 220 mg/dl, compared to 250 mg/dl in the meat-and-potatoes control group. Blood pressure also dropped and the Prudent Dieters lost weight. However, the study authors were obliged to note twenty-six deaths in the Prudent Diet group, including eight deaths from heart disease, versus only six deaths, none from heart disease, among those who ate meat three times a day. Dr. Jolliffe was dead by this time. He succumbed in 1961 to vascular thrombosis, although the obituaries listed the cause of death as complications from diabetes. The “compelling proof” that Stamler and others felt certain would vindicate wholesale tampering with American eating habits was not yet “nailed down.”

According to insiders promoting the diet-heart theory and the lipid hypothesis, the numbers involved in the Anti-Coronary Club experiment were too small to provide meaningful results. Dr. Irving Page urged a national diet-heart study involving one million men, in which the results of the Prudent Diet could be compared on a large scale with those on a diet high in meat and fat. With great media attention, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute organized the stocking of food warehouses in six major cities, where men on the Prudent Diet could get tasty polyunsaturated donuts and other fabricated food items free of charge. But a pilot study involving two thousand men resulted in exactly the same number of deaths in both the Prudent Diet and the control group. A brief report in Circulation, March 1968, stated that the study was a milestone “in mass environmental experimentation” that would have “an important effect on the food industry and the attitude of the public toward its eating habits.”40 But the million-man Diet-Heart Study was abandoned in utter silence “for reasons of cost.” Its chairman, Dr. Irving Page, died of a heart attack.

ALTHOUGH THE AHA HAD COMMITTED itself to the lipid hypothesis and the unproven theory that liquid vegetable oils afforded protection against heart disease, concerns about partially hydrogenated (industrially hardened) vegetable oils were sufficiently great to warrant the inclusion of the following statement in the organization’s 1968 statement on diet and heart disease: “Partial hydrogenation of polyunsaturated fats results in the formation of trans forms which are less effective than cis, cis [natural] forms in lowering cholesterol concentrations. It should be noted that many currently available shortening and margarines are partially hydrogenated and may contain little polyunsaturated fat of the natural cis, cis form.” The AHA printed one hundred fifty thousand statements but never distributed them. The shortening industry strongly objected, and a researcher named Fred Mattson of Procter & Gamble convinced Campbell Moses, medical director of the AHA, to remove the statement.41 The final AHA recommendations for the public contained three major points—restrict calories, substitute liquid oil for saturated fats like butter, and reduce cholesterol in the blood through diet.

Other organizations soon fell in behind the AHA in urging the replacement of animal fat with vegetable oils. By the early 1970s the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI), the American Medical Association (AMA), the American Dietetic Association (ADA) and the National Academy of Science (NAS) had all endorsed the lipid hypothesis, urging Americans in the “at risk” category to avoid animal fats.

Since Kritchevsky’s early rabbit studies, many other trials had shown that serum cholesterol can be lowered by increasing ingestion of liquid polyunsaturated oil.* But proof that lowering serum cholesterol levels could stave off CHD remained elusive. That did not prevent the American Heart Association from calling for “modified and ordinary foods” to support a dietary shift toward newfangled oils and away from traditional fats. These foods, said the AHA literature, should be made available to the consumer, “reasonably priced and easily identified by appropriate labeling. Any existing legal and regulatory barriers to the marketing of such foods should be removed.”42

The man who made it possible to remove any “existing legal and regulatory barriers” was Peter Barton Hutt, a food lawyer for the prestigious Washington, DC law firm of Covington and Burling. Hutt once stated, “Food law is the most wonderful field of law that you can possibly enter.”43 After representing the edible oil industry at his law firm, he temporarily left to become the FDA’s general counsel in 1971.

The regulatory barrier the AHA was referring to, and that Hutt would challenge, was the Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act of 1938, which stated that “there are certain traditional foods that everyone knows, such as bread, milk, and cheese, and that when consumers buy these foods, they should get the foods that they are expecting… [and] if a food resembles a standardized food but does not comply with the standard, that food must be labeled as an ‘imitation.’”

The 1938 Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act became law partly in response to consumer concerns about the adulteration of ordinary foodstuffs. Chief among those needing protection were butter and olive oil—foods with a tradition of suffering competition from imitation products. As the FDA’s general counsel, Hutt guided his agency through the legal and congressional hoops to establish a new “Imitation Policy” in 1973. This new policy attempted to provide for “advances in food technology” and give “manufacturers relief from the dilemma of either complying with an outdated standard or having to label their new products as ‘imitation’… [since] such products are not necessarily inferior to the traditional foods for which they may be substituted.”44 Hutt considered the word “imitation” as oversimplified, inaccurate and “potentially misleading to consumers.” The new regulations defined “inferiority” as “any reduction in content of an essential nutrient that is present at a level of two percent or more of the US Recommended Daily Allowance (RDA).” The new imitation policy meant that imitation sour cream, made with vegetable oil and fillers like guar gum and carrageenan, need not carry an imitation label as long as added minerals and artificial vitamins brought key nutrient levels up to the same amounts as those in real sour cream. Coffee creamers, imitation egg mixes, processed cheeses and imitation whipped cream no longer required the imitation label, but could be sold as real and beneficial foods, low in cholesterol and rich in polyunsaturated fatty acids.

These new regulations were adopted without the consent of Congress, continuing the trend, instituted under Nixon, of the White House using the FDA to promote certain social agendas through government food policies. This policy effectively increased the lobbying clout of special interest groups, such as the edible oil industry, and short-circuited public participation in the regulatory process. The FDA’s new imitation language allowed food processing innovations that manufacturers regarded as “technological improvements” to enter the marketplace without the onus of oversight brought on by greater consumer awareness and congressional supervision. Along with “technological improvements” the FDA ushered in the era of ersatz foodstuffs—convenient counterfeit products that were weary, stale, flat and immensely profitable.

CONGRESS VOICED NO OBJECTION TO the FDA’s usurpation of its powers, but entered the contest on the side of the lipid hypothesis. The Senate Select Committee on Nutrition and Human Needs, chaired by George McGovern during the years 1973 to 1977, actively promoted the use of vegetable oils. “Dietary Goals for the United States,” published by the committee, cited U.S. Department of Agriculture data on fat consumption, and stated categorically that “the overconsumption of fat, generally, and saturated fat in particular… have been related to six of the ten leading causes of death” in the United States. The report urged the American populace to reduce overall fat intake and to substitute polyunsaturated vegetable oils for saturated fat from animal sources—margarine and corn oil for butter, lard and tallow.45 Opposing testimony included a moving letter by Dr. Fred Kummerow of the University of Illinois urging a return to traditional whole foods and warning against consumption of soft drinks. In the early 1970s, Kummerow had shown that trans fatty acids in partially hydrogenated vegetable oil caused increased rates of heart disease in pigs.46 This was a direct challenge to the lipid hypothesis driving the country’s food choices, but his letter remained buried in the voluminous report. A private endowment allowed him to continue his research as government funding agencies such as National Institutes of Health refused to give Kummerow further grants.

McGovern committee members were also aware of another damning unpublished study, this time on calves and cholesterol. While the study was not mentioned in the committee’s final report, it compared calves fed saturated fat from tallow and lard with those fed unsaturated fat from soybean oil. The calves fed tallow and lard did indeed show higher plasma cholesterol levels than the calves fed soybean oil, and researchers found fat streaking in their aortas. But the calves fed soybean oil showed a decline in calcium and magnesium levels in the blood, possibly due to inefficient absorption. They utilized vitamins and minerals inefficiently, showed poor growth, poor bone development, and had abnormal hearts.* More cholesterol per unit of dry matter was found in the calves’ aortas, livers, muscle, fat and coronary arteries. These findings led the investigators to an important conclusion: the lower blood cholesterol levels in the soybean-oil-fed calves may have been the result of cholesterol transfer from the blood to other tissues. The calves in the soybean oil group also collapsed when they were forced to move around, and they were unaware of their surroundings for short periods. They also had rickets and diarrhea.47 These unfortunate side effects of a vegetable oil diet in calves should have served as a warning on the effects of the diet-heart theory applied to children, but no one on the committee was paying attention.

One person who was paying attention was Mary G. Enig, a graduate student in the lipids department at the University of Maryland. When she read the McGovern committee final report, she was puzzled. Enig was familiar with Kummerow’s research, and she knew that the consumption of animal fats in America was not on the increase—quite the contrary, use of animal fats had declined steadily since the turn of the century. A report in the Journal of American Oil Chemists—which the McGovern committee did not use—showed that animal fat consumption had declined from 104 grams per person per day in 1909 to 97 grams per day in 1972, while vegetable fat intake had tripled from a mere 21 grams to almost 60.48 Total per capita fat consumption had tripled over the period, but this increase was mostly due to an increase in unsaturated fats from vegetable oils—with 50 percent of the increase coming from liquid vegetable oils and about 41 percent from margarines and shortenings made from vegetable oils.

She also knew about a number of studies that directly contradicted the McGovern committee’s conclusions that “there is… a strong correlation between dietary fat intake and the incidence of breast cancer and colon cancer,” two of the most common cancers in America. All she had to do was look to other countries. Greece, for example, had less than one-fourth the rate of breast cancer compared to Israel, but the same dietary fat intake.49 Spain had only one-third the breast cancer mortality of France and Italy, but the total dietary fat intake was slightly greater.50 Puerto Rico, with a high animal fat intake, had very low rates of breast and colon cancer.51 The Netherlands and Finland both used approximately 100 grams of animal fat per capita per day, but breast and colon cancer rates were almost twice as high in the Netherlands compared to Finland.52 The Netherlands consumed 53 grams of vegetable fat per person compared to 13 in Finland. A study from Cali, Columbia, found a fourfold excess risk for colon cancer in the higher economic classes, which used less animal fat than the lower economic classes.53 A study on Seventh-Day Adventist physicians, who avoid meat, especially red meat, found they had a significantly higher rate of colon cancer than non-Seventh-Day Adventist physicians.54

Enig analyzed the U.S. Department of Agriculture data that the McGovern committee had used and concluded that it showed a strong positive correlation between total fat and vegetable fat consumption to total cancer deaths, breast and colon cancer mortality, and breast and colon cancer incidence. The data also showed an essentially strong negative correlation or no correlation between animal fat consumption and total cancer deaths, breast and colon cancer mortality, and breast and colon cancer incidence. In other words, the data that the McGovern committee used showed that vegetable oils seemed to predispose someone to cancer while animal fats seemed to protect against cancer. She also noted that the analysts for the committee had manipulated the data in inappropriate ways—for example adding when they should have subtracted—in order to obtain mendacious results in favor of vegetable oils.

Enig submitted her findings to the Journal of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology (FASEB), in May 1978, and her article was published in the FASEB’s Federation Proceedings55 in July of the same year—an unusually quick turnaround. The assistant editor, responsible for accepting the article, died of a heart attack shortly thereafter. Enig’s paper noted that the correlations pointed a finger at the trans fatty acids and called for further investigation.

Enig’s paper sent alarm bells through the edible oil industry. In early 1979, while still a graduate student, she received a visit from S. F. Reipma of the National Association of Margarine Manufacturers. Reipma was visibly annoyed. He explained that both his association and the Institute for Shortening and Edible Oils (ISEO) kept careful watch to prevent articles like Enig’s from appearing in the scientific literature. He claimed that Enig’s paper should never have been published. While he thought that ISEO was “watching out,” he admitted, “we left the barn door open, and the horse got out.” Reipma challenged Enig’s use of the USDA data, claiming that it was in error. He knew it was in error, he said, “because we give it to them.”

A few weeks later, Reipma paid Enig a second visit, this time in the company of Thomas Applewhite, an advisor to the ISEO and representative of Kraft Foods, Ronald Simpson with Central Soya, and an unnamed representative from Lever Brothers. They carried with them—in fact, waved them in the air in indignation—a two-inch stack of newspaper articles, including one that appeared in the National Enquirer, all reporting favorably on Enig’s Federation Proceedings article. Applewhite’s face flushed red with anger when Enig repeated Reipma’s statement that “they had left the barn door open and the horse got out,” and his admission that the margarine industry had sabotaged the Department of Agriculture food data.

In spite of Enig’s efforts to right the wrongs of the McGovern committee, the Committee’s recommendations bolstered dietary trends already in progress—the increased use of vegetable oils, especially in the form of partially hydrogenated margarines and shortenings. In 1976, the FDA established GRAS (Generally Recognized as Safe) status for hydrogenated soybean oil. A report prepared by the Life Sciences Research Office of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology (LSRO-FASEB) concluded, “There is no evidence in the available information on hydrogenated soybean oil that demonstrates or suggests reasonable ground to suspect a hazard to the public when it is used as a direct or indirect food ingredient at levels that are now current or that might reasonably be expected in the future.”56 Armed with this assurance, the vegetable oil industry turned its attention to replacing animal fats with trans fats in the entire food supply.

WHILE THE U.S. GOVERNMENT ABANDONED its million-man diet-heart study “for reasons of cost,” plenty of funding became available for other studies through the National Heart, Blood, and Lung Institute (NHBLI). These studies would form the justification that allowed the scientific and popular literature promote the diet-heart theory and the lipid hypothesis.

First was the Framingham Study, ongoing for forty years, which found virtually no difference in coronary heart disease “events” for individuals with cholesterol levels between 205 mg/dL and 294 mg/dL—the vast majority of the U.S. population. Even for those with extremely high cholesterol levels—up to almost 1200 mg/dL—the difference in CHD events compared to those in the normal range was trivial.57 This did not prevent Dr. William Kannel, Framingham Study director in 1987, from making sweeping claims about the Framingham results. “Total plasma cholesterol,” he said, “is a powerful predictor of death related to CHD.”58 It wasn’t until more than a decade later that the real findings at Framingham were published—without fanfare—in the Archives of Internal Medicine, an obscure journal. “In Framingham, Massachusetts,” admitted Dr. William Castelli, Kannel’s successor, “the more saturated fat one ate, the more cholesterol one ate, the more calories one ate, the lower people’s serum cholesterol… we found that the people who ate the most cholesterol, ate the most saturated fat, ate the most calories weighed the least and were the most physically active.”59 In other words, those eating butter and other animal fats had the lowest major risk factors for heart disease—low cholesterol levels, normal body weight and high physical activity.

NHLBI’s Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial (MRFIT) also studied the relationship between heart disease and serum cholesterol levels, this time in three hundred sixty-two thousand men. Published in 1982, this trial found that annual deaths from CHD varied from slightly less than one per thousand at serum cholesterol levels below 140 mg/dL, to about two per thousand for serum cholesterol levels above 300 mg/dL, once again a trivial difference. Dr. John LaRosa of the American Heart Association claimed that the curve for CHD deaths began to “inflect” after 200 mg/dL, when in fact the “curve” was a very gradually sloping straight line that could not predict whether serum cholesterol above certain levels posed a significantly greater risk for heart disease. In addition, another key MRFIT finding—not reported in the media—was the unexpected fact that deaths from all causes (cancer, heart disease, accidents, infectious disease, kidney failure, etc.) were substantially greater for those men with cholesterol levels below 160 mg/dL.60

Considering the fact that orthodox medical agencies united together in their promotion of margarine and vegetable oils over animal foods containing cholesterol and saturated fat, it is surprising that researchers can cite only a handful of experiments indicating that dietary cholesterol has “a major role in determining blood cholesterol levels.” One of these was a study involving seventy male prisoners directed by Fred Mattson61—the same Fred Mattson, formerly of Procter & Gamble, who pressured the American Heart Association into removing any reference to hydrogenated fats from their diet-heart statement a decade earlier. Funded in part by P&G, the research contained a number of serious flaws: selection of subjects for the four groups studied was not randomized; the experiment inexcusably eliminated “an equal number of subjects with the highest and lowest cholesterol values”; twelve additional subjects dropped out, leaving some of the groups too small to provide valid conclusions; and statistical manipulation of the results was shoddy. But the biggest flaw was the fact that the subjects receiving cholesterol did so in the form of reconstituted powder—an artificial diet. Mattson’s discussion did not even address the possibility that the liquid formula diet he used might affect blood cholesterol levels differently than a diet of whole foods—even as other comparable studies indicated that this is the case. The culprit, in fact, in liquid protein diets appears to be oxidized cholesterol, formed during the high-temperature drying process. Oxidized cholesterol seems to initiate a buildup of plaque in the arteries.*62 It was also purified, oxidized cholesterol (usually mixed with vegetable oil) that Kritchevsky and others used in their experiments on vegetarian rabbits.

The NHLBI had argued that a diet study using whole foods and involving large numbers of Americans would be too difficult to design and too expensive to carry out, but the agency did have funds available to sponsor the massive Lipid Research Clinics Coronary Primary Prevention Trial (LRC-CPPT) in which all subjects were placed on a diet low in cholesterol and saturated fat. The researchers divided the subjects into two groups, one of which took a cholesterol-lowering drug and the other a placebo, but placed both groups on a low-cholesterol, low–saturated fat diet. Working behind the scenes, but playing a key role in both the design and implementation of the trials, was the same Dr. Fred Mattson.

An interesting feature of this particular study was the fact that a good part of the trial’s one-hundred-and-fifty-million-dollar budget was devoted to sessions in which trained dietitians taught both groups of study participants how to choose “heart-friendly” foods—margarine, egg replacements, processed cheese, baked goods made with vegetable shortenings—in short, the vast array of manufactured foods awaiting consumer acceptance. As both groups received dietary indoctrination, study results could support no claims about the relation of diet to heart disease. Nevertheless, when the results were released, both the popular press and the medical journals portrayed the Lipid Research Clinics’ trials as the long-sought proof that animal fats were the cause of heart disease. Rarely mentioned in the press reports was the ominous fact that the group taking the cholesterol-lowering drugs had an increase in deaths from cancer, stroke, violence and suicide.63

The Lipid Research Clinics’ researchers claimed that the group taking the cholesterol-lowering drug had a 17 percent reduction in the rate of CHD, with an average cholesterol reduction of 8.5 percent. This allowed LRC trials director Basil Rifkind to claim that “for each 1 percent reduction in cholesterol, we can expect a 2 percent reduction in CHD events.” The statement was widely circulated even though it represented a completely invalid representation of the data, especially in light of the fact that when the lipid group at the University of Maryland analyzed the LRC data, they found no difference in CHD events between the group taking the drug and those on the placebo.64 Ironically, just three years later, the Framingham Study group published follow-up data on the original Framingham subjects. Their finding: for each 1 percent mg/dl drop of cholesterol there was an 11 percent increase in coronary and total mortality. In other words, the lower the cholesterol levels of the participants, the greater their risk of death.65

A number of clinicians and statisticians participating in a 1984 Lipid Research Clinics Conference workshop were highly critical of the manner in which the LRC researchers had tabulated and manipulated the results. The conference, in fact, went very badly for the NHLBI, with critics of the lipid hypothesis almost outnumbering supporters.

Dissenters were again invited to speak briefly at the NHLBI-sponsored National Cholesterol Consensus Conference held later that year, but their views were not included in the panel’s report, for the simple reason that the NHLBI staff generated the report before the conference convened. University of Maryland researcher Dr. Beverly Teter discovered this fact when she picked up some papers by mistake just before the conference began, and found they contained the consensus report, already written, with just a few numbers left blank. Kritchevsky represented the lipid hypothesis camp with a humorous five-minute presentation, full of ditties. Edward Ahrens, who pioneered earlier research to assess how dietary fats and cholesterol affected blood levels of cholesterol, nevertheless raised strenuous objections about the “consensus,” only to have the conference organizers tell him that he had misinterpreted his own data, and that if he wanted a conference to come up with different conclusions, he should pay for it himself.

The 1984 Cholesterol Consensus Conference final report was a whitewash, containing no mention of the evidence that conflicted with the diet-heart theory and the lipid hypothesis. Dissenting attendees found their names listed as speakers, but with no record of what they said.

One of the blanks was filled with the number two hundred. The document defined all those with cholesterol levels above 200 mg/dL as “at risk” and called for mass cholesterol screening, even though the most ardent supporters of the lipid hypothesis had surmised in print that two hundred forty should be the magic cutoff point. Such screening would, in fact, be required on a massive scale as the federal medical bureaucracy, by picking the number two hundred, had declared a large portion of the American adult population as “at risk.”* The report advocated the avoidance of saturated fat and cholesterol for all Americans now defined as “at risk,” and specifically advised the replacement of butter with margarine.

The Consensus Conference also provided a launching pad for the nationwide National Cholesterol Education Program, which had the stated goal of “changing physicians’ attitudes.” NHLBI-funded surveys had determined that while the general population had bought into the diet-heart theory and the lipid hypothesis, and was dutifully using margarine and buying low-cholesterol foods, the medical profession remained skeptical. All doctors in America received a large “Physicians Kit,” compiled in part by the American Pharmaceutical Association, whose representatives served on the NCEP coordinating committee. Doctors were taught the importance of cholesterol screening, the advantages of cholesterol-lowering drugs and the unique benefits of the Prudent Diet. Every doctor in America received a packet of NCEP materials, which recommended the use of margarine rather than butter. The men in white coats now served as hucksters for the vegetable oil industry.

IN NOVEMBER 1986, THE JOURNAL of the American Medical Association published a series on the Lipid Research Clinics’ trials, including “Cholesterol and Coronary Heart Disease: A New Era,” by longtime American Heart Association member Scott Grundy, MD, PhD.66 The article is a disturbing combination of euphoria and agony—euphoria at the forward movement of the anti-cholesterol juggernaut, and agony over the elusive nature of real proof. “The recent consensus conference on cholesterol… implied that levels between 200 and 240… carry at least a mild increase in risk, which they obviously do,” wrote Grundy. This directly contradicted an earlier statement in which Grundy claimed that the cause-and-effect connection was strong. Grundy called for “the simple step of measuring the plasma cholesterol level in all adults… those found to have elevated cholesterol levels can be designated as at high risk and thereby can enter the medical care system… an enormous number of patients will be included [italics added].” Who benefits from “the simple step” of measuring and monitoring cholesterol levels in all adults? Hospitals, laboratories, pharmaceutical companies, the vegetable oil industry, margarine manufacturers, food processors and, of course, medical doctors, just to name a few. “Many physicians will see the advantages of using drugs for cholesterol lowering,” wrote Grundy, even though “a positive benefit/risk ratio for cholesterol-lowering drugs will be difficult to prove.” In the thirty years since Grundy’s prediction, sales of cholesterol-lowering drugs have reached fourteen billion dollars per year, even though a positive risk/benefit ratio for such treatment has never emerged from the studies. Physicians, however, have “seen the advantages of using drugs for cholesterol lowering” as a way of creating patients out of healthy people.

Grundy was equally inconsistent about the benefits of dietary modification. “Whether diet has a long term effect on cholesterol remains to be proved,” he stated, but “public health advocates furthermore can play an important role by urging the food industry to provide palatable choices of foods that are low in cholesterol, saturated fatty acids, and total calories.” Such foods, almost by definition, contain liquid or partially hydrogenated vegetable oils containing trans fatty acids. Grundy knew that the trans fats were a problem, that they raised serum cholesterol and contributed to many diseases—he knew because a year earlier, at his request, Mary G. Enig, PhD, then in private practice, had sent him a package of data detailing numerous studies that gave reason for concern, which he acknowledged in a signed letter as “an important contribution to the ongoing debate.”67

Shortly thereafter, the Surgeon General’s Report on Nutrition and Health emphasized the importance of making low-fat foods more widely available. Project LEAN (Low-Fat Eating for America Now), sponsored by the J. Kaiser Family Foundation and a host of establishment groups—such as the American Heart Association, the American Dietetic Association, the American Medical Association, the USDA, the National Cancer Institute, Centers for Disease Control and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute—announced a publicity campaign to “aggressively promote foods low in saturated fat and cholesterol in order to reduce the risk of heart disease and cancer.”68

Meanwhile, studies contradicting the diet-heart theory and the lipid hypothesis continued to accumulate. In 1988, the statistician Russell Smith, PhD, in consultation with Edward R. Pinckney, MD, published a summary of all the diet and cholesterol studies to date. Diet, Blood Cholesterol and Coronary Heart Disease: A Critical Review of the Literature catalogs the many papers that received no attention from the media, most of which refuted the cholesterol dogma or were inconclusive. In summary, Smith stated, “One need not go beyond the food consumption studies to know that the diet-CHD hypothesis is totally and unequivocally incorrect. These studies, combined with common knowledge, demonstrate clearly that the foods targeted by the NHLBI/AHA alliance as raising blood cholesterol and, therefore, indirectly causing atherosclerosis, decreased (animal fats) or remained constant (dietary cholesterol) during the ‘epidemic.’ The only trend which paralleled the recorded CHD mortality curve was that of vegetable fats… Attributing the ‘epidemic’ to animal fat consumption… is totally illogical and defies even the most elementary principles of scientific reasoning.”69

Regarding the presentation of the cholesterol theory in the media, Smith was scathing: “Many hundreds and probably thousands of articles on diet and heart disease have been published in the last fifteen years in newspapers and magazines. Almost none of these articles have accurately reflected the known scientific facts, and many have given the public totally false or highly misleading information.”70

For example, the press did not report on a multiyear British study involving several thousand men, published in 1983, half of whom were asked to reduce saturated fat and cholesterol in their diets, to stop smoking and to increase the amounts of unsaturated oils such as margarine and vegetable oils. After one year, those on the “good” diet had 100 percent more deaths than those on the “bad” diet, in spite of the fact that those men on the “bad” diet continued to smoke! But in describing the findings, the study’s author ignored these results in favor of the politically correct conclusion: “The implication for public health policy in the U.K. is that a preventive programme such as we evaluated in this trial is probably effective.”71

Numerous surveys of traditional populations have also yielded information that is an embarrassment to proponents of the diet-heart theory. For example, a study comparing Jews when they lived in Yemen and ate fats solely of animal origin to Yemenite Jews living in Israel, whose diets contained margarine and vegetable oils, revealed little heart disease or diabetes in the former group but high levels of both diseases in the latter.*72 A comparison of populations in northern and southern India revealed a similar pattern. People in northern India consumed seventeen times more animal fat, but had an incidence of coronary heart disease seven times lower than people in southern India.73 The Masai and kindred tribes of Africa subsist largely on milk, meat and blood. They are free from coronary heart disease and have low blood cholesterol levels.74 Eskimos eat liberally of animal fats from fish and marine animals. On their native diet they are free of disease and exceptionally hardy.75

Colin Campbell, coauthor of the famous China Study, claims that his extensive study of diet and disease patterns in China found that those on plant-based diets suffered fewer health problems than those whose diets contained large amounts of animal foods. However, the researchers actually discovered that people living in the region in which the populace consumed large amounts of whole milk had half the rate of heart disease as several districts with low levels of animal consumption.76 Several Mediterranean societies have low rates of heart disease even though fat—including highly saturated fat from lamb, sausage and goat cheese—comprises a large portion of their caloric intake. The inhabitants of Crete, for example, are remarkable for their good health and longevity.77 A study of Puerto Ricans revealed that, although they consumed large amounts of animal fat (mostly as lard), they had a very low incidence of colon and breast cancer.78 A study of the long-lived inhabitants of Soviet Georgia revealed that those who ate the most fatty meat lived the longest.79 In Okinawa, where the average life span for women is eighty-four years—longer than in the rest of Japan—the inhabitants eat generous amounts of pork and seafood and do all their cooking in lard.*80 None of these studies appears in feature articles in the New York Times.

Researchers often attribute the relative good health of the Japanese, who have the longest life span of any nation in the world, to a low-fat diet. Although the Japanese eat few dairy fats, the notion that their diet is low in fat is a myth; rather, it contains moderate amounts of animal fats from eggs, pork (in popular foods like Spam), chicken, beef, seafood and organ meats. What they do not consume (or at least did not consume until recently) is a lot of vegetable oil, white flour or processed food (although they do eat white rice). The life span of the Japanese has increased since the Second World War with an increase in animal fat and protein in the diet.81 Those who point to Japanese statistics to promote the low-fat diet fail to mention the fact that the Swiss live almost as long on one of the fattiest diets in the world. Tied for third in the longevity stakes are Austria and Greece—both with high-fat diets.82

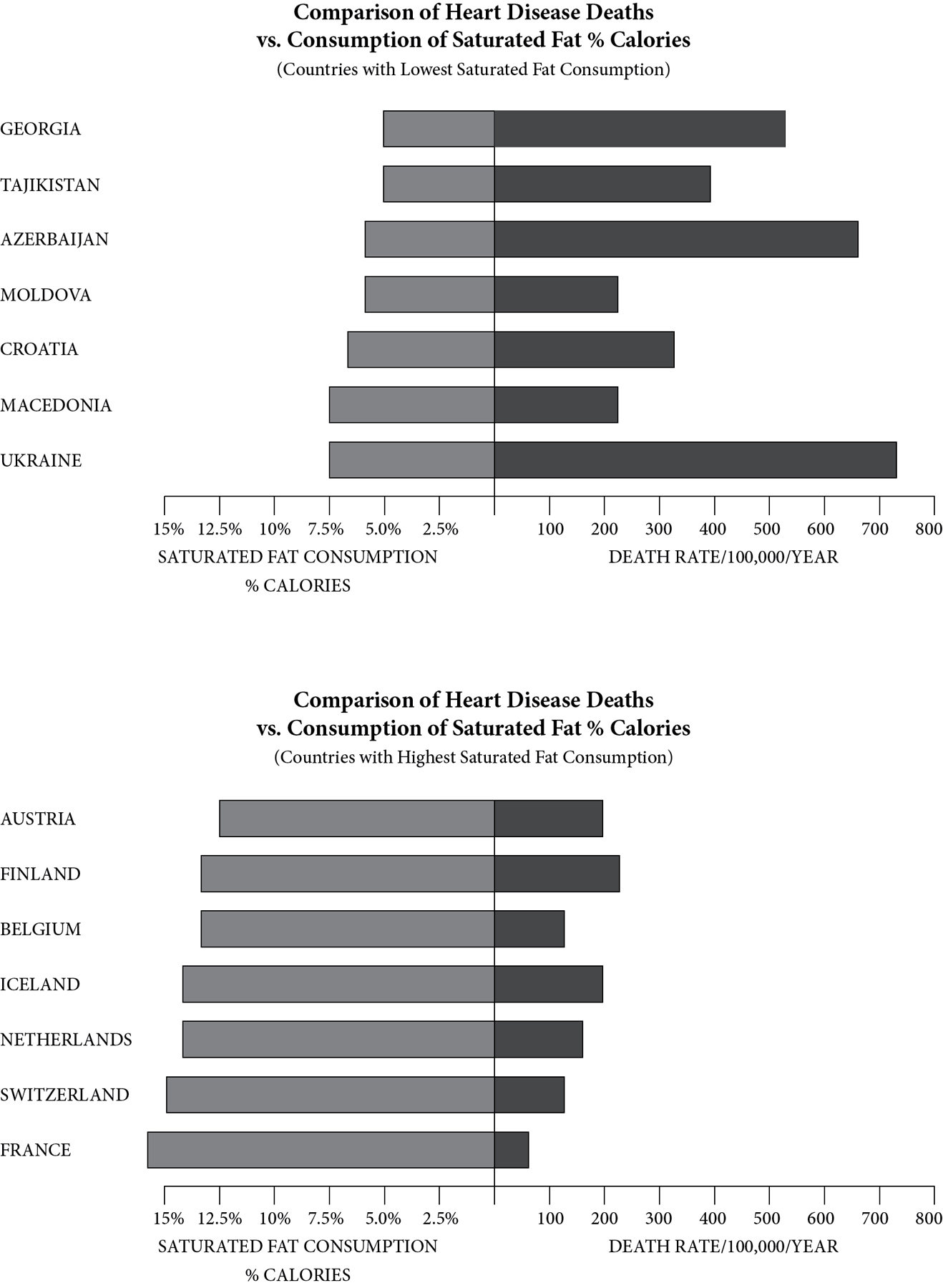

As a final example, let us consider the French. Anyone who has eaten his way across France has observed that the French diet is loaded with saturated fats in the form of butter, eggs, cheese, cream, liver, meats and rich pâtés. Yet the French have a lower rate of coronary heart disease than many other Western countries. In the United States, over three hundred of every hundred thousand middle-aged men die of heart attacks each year; in France the rate is half of that, at one hundred forty-five per hundred thousand. In the Gascony region, where goose and duck liver form a staple of the diet, this rate is remarkably low: eighty per hundred thousand.83 This phenomenon has gained international attention as “The French Paradox.” But other European countries show paradoxical patterns as well. The highest rates of saturated fat consumption in Europe occur in France, followed by Switzerland, the Netherlands, Iceland, Belgium, Finland and Austria. Yet these same countries have the lowest rates of death from heart disease in Europe, while the countries with low rates of saturated fat consumption have higher rates of CHD.84

In spite of these glaring facts, the campaign to promote vegetable oils had worked very well. By the 1990s, the promoters had succeeded, by slick manipulation of the press and of scientific research, in transforming America into a nation that was well and truly oiled. Consumption of butter had bottomed out at about 4 grams per person per year (about one teaspoon per day), down from almost 18 grams at the turn of the century. Use of lard and tallow was down by two-thirds. Margarine consumption had jumped from less than 2 grams per person per day in 1909 to about 11 in 1960.85 Since then margarine consumption figures have changed little, remaining at about 11 grams per person per day—perhaps because knowledge of margarine’s dangers has been slowly seeping out to the public. However, for many years most of the trans fats in the American diet weren’t from margarine alone, but from shortening used in fried and fabricated foods. American shortening consumption of 10 grams per person per day held steady until the 1960s, although the content of that shortening had changed from mostly lard, tallow or coconut oil—all natural fats—to partially hydrogenated soybean oil. Then shortening consumption shot up and by the 1990s had tripled to almost 30 grams per person per day.

Source: U.S. Department of Agriculture

But the most dramatic overall change in the American diet was the huge increase in the consumption of liquid vegetable oils, from slightly less than 2 grams per person per day in 1909 to over 30—a fifteenfold increase. Now that the dangers of hardened trans fats have become common knowledge, Americans are consuming more liquid vegetable oils than ever.

BY THE EARLY 1980s, ONLY one large source of saturated animal fat in American fast food remained—the tallow in fast-food fryers. McDonald’s and other fast-food restaurants used beef or lamb tallow, and with good reason.* Highly saturated tallow is stable, can be reused many times, and gives a delicious, crispy final product. That was soon to change, thanks to the Center for Science in the Public Interest (CSPI).

One of America’s most influential and vocal consumer-advocacy group, CSPI was founded in 1972, the year that Michael Jacobson, CSPI’s executive director, published Eaters’ Digest, a book filled with anti-saturated-fat rhetoric.

CSPI’s 1988 publication, Saturated Fat Attack, condemned a long list of processed foods said to be made with coconut oil, palm oil, tallow, butter or lard. (Actually, processors used mostly partially hydrogenated oil for snack foods and baked goods, but often included a small amount of other fats and oils, which were, of course, listed on the label.) There were a few holdouts on the list, however: Hi Ho Crackers were made with coconut oil, Uneeda Biscuits were made with lard, Sara Lee Croissants were made with butter, and Pepperidge Farm used a blend that contained a lot of coconut oil.86

But it was the fast-food chains that received the brunt of Jacobson’s wrath, because they used a blend of 91–95 percent beef fat or 100 percent palm oil for frying. Jacobson and CSPI orchestrated well-publicized demonstrations in front of McDonald’s and a postcard campaign to the corporate offices of the fast-food chains to protest the use of these “artery-clogging” saturated fats for frying.

CSPI launched its campaign against “saturated” frying fats in 1984 and continued its efforts into 1986 when the organization added “tropical oils” to the list of supposed villains in the American diet. The campaign was successful; most fast-food restaurants soon switched to partially hydrogenated shortening. Movie theaters gave in very quickly as well—replacing the villainous coconut oil in their popcorn with shortening containing artificial butter flavor.†

While problems with trans fats in partially hydrogenated oil were well known at this time, CSPI continued to defend them throughout the decade. A 1987 article by Elaine Blume, published in CSPI’s Nutrition Action newsletter, read like oil industry propaganda. Blume wrote: “From margarine to Tater Tots, partially hydrogenated vegetable oils play a major role in our food supply… In fact, hydrogenated oils don’t pose a dire threat to health… Improving on Nature… Manufacturers hydrogenate… these vegetable oils so they won’t become rancid while they sit on shelves, or during frying… it seems unlikely that hydrogenation contributes much to our burden of heart disease… The fact that hydrogenated oils appear to be relatively benign is cause for thanks, because these fats are everywhere.”

Blume was at it again in March 1988 with another article, “The Truth About Trans.” In it, she claimed: “Hydrogenated oils aren’t guilty as charged… All told, the charges against trans fat just don’t stand up. And by extension, hydrogenated oils seem relatively innocent… As for processed foods, you’re better off choosing products made with hydrogenated soybean, corn, or cottonseed oil.” This article was widely disseminated; Michael Jacobson provided it as a handout to members of the Maryland legislature during hearings when the University of Maryland lipids research group tried to introduce labeling of trans fatty acids in the state.

But by 1990, CSPI could no longer defend the indefensible. In October of that year, Bonnie Liebman, CSPI director of nutrition, published an article, “Trans in Trouble,” which referred to recent studies by Dutch scientists showing that trans fats raised cholesterol. “That’s not to say trans fatty acids are artery-cloggers,” she wrote; “the fats in our foods may affect cholesterol differently than those used in the Dutch experiment… The Bottom Line… Trans, shmans. You should eat less fat… Don’t switch back to butter… use a soft tub diet margarine.”

On October 20, 1993, CSPI had the chutzpah to call a press conference in Washington, DC, and lambast the major fast-food chains for doing what CSPI coerced them into doing, namely, using partially hydrogenated vegetable oils in their deep-fat fryers. On that date, CSPI reversed its position after an onslaught of adverse medical reports linking trans fatty acids in these processed oils to coronary heart disease and cancer. Instead of accepting the blame, CSPI claimed that the fault lay with the major fast-food chains, including McDonald’s, Burger King, Wendy’s and Kentucky Fried Chicken, because they “falsely claim to use ‘100 percent vegetable oil’ when they actually use hydrogenated shortening.”*

According to the CSPI press release, “In 1984, CSPI organized the first national campaign to pressure fast-food restaurants and food companies to stop frying with beef fat and tropical oils, which are high in the cholesterol-raising saturated fats that increase the risk of heart disease. After six years of public pressure—including full-page newspaper ads placed by Nebraska millionaire and cholesterol-crusader Phil Sokolof—the industry finally relented in 1990. But instead of switching to vegetable oil for frying, CSPI’s research shows, the companies opted for hydrogenated shortenings, which have a longer shelf life and can be used longer in deep-fat fryers.”

In December 1992, Liebman wrote: “We’ve been crying ‘foul’ for some time now, as the margarine industry has tried to convince people that eating margarine was as good for their hearts as aerobic exercise… And we warned folks several years ago that trans fatty acids could be a problem… That’s especially true now that we know that trans fatty acids are harmful, but we don’t know how much trans are in different foods.” Of course, CSPI had issued no such warning, but had defended trans fats for more than five years. And they offered no apology for falsely demonizing traditional fats. “Don’t switch back from margarine to butter,” wrote Liebman, “try diet or whipped margarine… use a liquid margarine.”

CSPI’s campaign was wildly successful. It is impossible to measure the suffering and grief that Liebman and Jacobson—as leaders of the major nutrition “activist” consumer organization—have inflicted on many millions of an unknowing public. Thanks to CSPI, healthy traditional fats almost completely disappeared from the food supply, first replaced by manufactured trans fats known to cause many diseases, and then more recently, by dangerously rancid liquid oils. Jacobson was equally successful going after the popcorn in movie theaters so that this good dietary source of coconut oil—one of the supremely healthy fats on the planet—disappeared. “Today,” bragged Jacobson, “‘no tropical oils’ is a badge of honor worn by many food packages.”

Who benefits from the ongoing campaign against saturated fat? First and foremost, the soybean industry. Eighty percent of all oil, whether partially hydrogenated or liquid, used in processed foods in the United States comes from soybeans, as does 70 percent of all liquid oil sold in bottles to consumers. CSPI claims that its support comes from subscribers to its Nutrition Action newsletter, which continues even today to issue hysterical warnings against “artery-clogging” fats in steak, whole milk and fettuccine Alfredo. The one million subscribers provide more than 70 percent of CSPI’s thirteen-million-dollar annual income, according to one report, but CSPI is extremely secretive about the value of its assets, the salaries it pays and the use of its revenues. If CSPI has large donors, they’re not telling who they are, but in fact, in CSPI’s January 1991 newsletter, Jacobson notes that “our effort was ultimately joined… by the American Soybean Association.”87

Once the idea that saturated fats cause heart disease took hold, other modern diseases fell in line. The official organizations to combat stroke, Alzheimer’s, cancer, diabetes, autoimmune disease, multiple sclerosis, obesity and even infertility found an easy scapegoat in saturated fats, using evidence that is even sketchier than that used to indict saturated fats for heart disease—anything to deflect attention away from the truly dangerous ingredients in the modern industrial diet.

ON APRIL 30, 1996, SENIOR researcher David Kritchevsky received the American Oil Chemists’ Society’s Research Award in recognition of his accomplishments as a “researcher on cancer and atherosclerosis as well as cholesterol metabolism.” His accomplishments include coauthorship of more than three hundred seventy research papers, one of which appeared a month later in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition.88 This “Position paper on trans fatty acids” noted, “A controversy has arisen about the potential health hazards of trans unsaturated fatty acids in the American diet.”

The controversy dates back to 1954. In the rabbit studies that launched Kritchevsky on his career, the researcher actually found that cholesterol dissolved in Wesson oil “markedly accelerated” the development of cholesterol-containing low-density lipoproteins; and cholesterol fed with shortening gave cholesterol levels twice as high as cholesterol fed alone.89 The unavoidable conclusion: vegetable oils, and particularly partially hydrogenated vegetable oils, are bad news.

But Kritchevsky’s “Position paper on trans fatty acids” took no position at all. Studies have given contradictory results, said the author, and the amount of trans in the average American diet is very difficult to determine. As for labeling, the study claimed, “There is no clear choice of how to include trans fatty acids on the nutrition label. The database is insufficient to establish a classification scheme for these fats.” There may be problems with trans, said the senior researcher, but their use “helps to reduce the intake of dietary fats higher in saturated fatty acids. Also, vegetable fats are not a source of dietary cholesterol, unlike saturated animal fats.” Kritchevsky and his coauthors concluded that physicians and nutritionists should “focus on a further decrease in total fat intake and especially the intake of saturated fat… A reduction in total fat intake simplifies the problem, because all fats in the diet decrease and choices are unnecessary… We may conclude,” wrote Kritchevsky and his colleagues, “that consumption of liquid vegetable oils is preferable to solid fats.”

Two years later, a symposium entitled “Evolution of Ideas about the Nutritional Value of Dietary Fat” reviewed the many flaws in the lipid hypothesis and highlighted a study in which mice fed purified diets died within twenty days, while whole milk kept the mice alive for several months.90 One of the participants was David Kritchevsky, who noted that the use of low-fat diets and drugs in intervention trials “did not affect overall CHD mortality.” Ever with a finger in the wind, this influential Founding Father of the lipid hypothesis concluded thus: “Research continues apace and, as new findings appear, it may be necessary to reevaluate our conclusions and preventive medicine policies.”

Fast-forward to the present, when many scientists and writers have exposed the manipulation and fraud in heart disease research: the establishment is sticking to its story. Cholesterol and saturated fat, particularly saturated animal fat, remain public enemy number one, the greatest villains in the Western diet. Trans fats are largely gone, but liquid vegetable oils—possibly more dangerous—have taken their place, used in fried foods, processed foods and “healthy” soft spreads.

MUCH OF WHAT AMERICANS BELIEVE about nutrition and have put into practice comes from popular magazines, which for decades have derived a large portion of their advertising revenues from the industrial food industry—think back to advertisements for Crisco in the 1912 Home Directory. Today, the practice continues to shape American eating habits.

The American Council on Science and Health, which describes its mission as ensuring “that peer-reviewed mainstream science reaches the public, the media, and the decision-makers who determine public policy,” tracks nutrition reporting in major magazines. In a 2001 report, fourteen out of twenty magazines received a rating as “excellent” or “good” sources of nutrition advice. (The three magazines rated excellent were Parents, Cooking Light and Good Housekeeping.) The report recorded as good news the fact that “for the first time since these surveys began, no magazine ranked as a poor source.” What this means is that the food industry has control of all the major magazines, and not one of them can be expected to publish anything but the conventional dogma that saturated fat is bad for all ages, even babies and little children.91

At eatingwell.com you can read today about the daily diets of six “nutrition experts,” as virtuous as virtuous nutrition experts can be. Lots and lots of low-fat foods in these diets—oyxmoronic low-fat sour cream and low-fat cheese—whole-grain foods like granola and whole wheat pasta, tofu, fish, 2 percent milk, and politically acceptable fast food like veggie burgers. Most of them admit to giving in to temptations like chocolate, ice cream, white bread, cake or pretzels. One “expert” drinks six diet sodas per day.

This advice is no different from what comes out of our universities, which are also recipients of food industry largesse. An August 2008 Health and Nutrition Letter from Tufts University, sent to students and dietitians, provides a list of thirty dietary suggestions, including lots of vegetables; lots of whole grains with just a very thin smear of spread on your bread; cooking in vegetable oils, no butter; less meat; more canned beans; less salt; and iced tea, black coffee or mineral water to drink. The article recommends eating from a small plate, never eating everything on your plate and never, ever eating seconds. The author does not provide any suggestions on what to do when the cravings hit just before bedtime, when the body tries to compensate for this virtuous starvation diet by making you eat a half-gallon of ice cream or a whole bag of potato chips.

Tufts nutrition professor Alice Lichtenstein has sided with the food processing industry throughout her career. As Americans make attempts to avoid processed foods, Lichtenstein declares that it is fine to reformulate real foods like meat and milk into low-fat versions “because you are focusing specifically on taking out saturated fat. But for other products such as cookies and brownies, it’s not that useful.” In other words, it’s okay for consumers to consume lots of industrial fats and oils in baked goods, but not the natural fats in cheese and meat.92

What happens when you try to eat according to the current U.S. government guidelines? The San Francisco Chronicle reported on a group of four food and wine staffers from their offices who took the following mission upon themselves: “Spend two weeks following the US government’s new [2010] dietary guidelines, glow smugly with the virtue and newfound health, then report on the findings.” After fourteen days of chickpeas, skim milk, soy milk, rice cakes, kale and carrot sticks, the intrepid group discovered that they all felt “constrained and deprived.” Blake Gray, one of the participants, summed it up: “I miss the pure pleasure of choosing the food that sounds most delicious and savoring each morsel without wondering what kind of oil it was cooked in. If I have to give some years off my life for this pleasure, I’m willing to do it—if only I knew in advance how many years I’m forfeiting.” The group also found that following the guidelines was very difficult to do, requiring the help of calorie, fat and sodium lists to figure out whether they could have an additional piece of cheese or a cookie for dessert; and while the guidelines did steer them away from junk food, they found it difficult to reach their vegetable and grain quota. One participant observed that it was hard to “round people up for a nice meal of chick-pea stew,” noting that she felt more isolated, with the world looking “a bit bleak.” In short, hiding behind a pile of platitudes against processed foods, the guidelines offer a useless plan for real people living in the real world who want to eat real food.93 With the vegetable oil industry pulling the strings in the background, the universities, the media, medical institutions and the government all sing the same sad song, making every effort to mislead a very confused public, which ricochets between virtuous, abstemious eating and indulgence in processed foods.

REDUCTIONIST TUNNEL VISION CAN LEAD to ludicrous conclusions, a prime example being the 2008 Overall Nutritional Quality Index (ONQI), developed by a “panel of twelve of the nation’s foremost experts on nutrition” at Yale University’s Griffin Prevention Research Center. The august experts rated commonly consumed foods on a scale of one to one hundred, with one hundred being the “healthiest,” using a complex mathematical formula that looks at selected nutrients in a particular food, as well as the amount of fat, sugar, sodium, cholesterol, calories, glycemic load and other factors. The top-rated food under the ONQI system? Broccoli! All but one of the foods rated ninety and above are fruits and vegetables—radish gets a ninety-nine—the exception being nonfat milk with a ninety-one. Meats and seafood range from the twenties to the eighties in this system, with the lower numbers assigned to fatty cuts of meat such as baby back ribs and chicken wings. Obviously nonnutritious foods such as Popsicles, cheese puffs and sodas received ratings below twenty, but so do healthy traditional foods like fried eggs, salami and bacon.94 Nutrient-dense foods—prized by traditional cultures as absolutely necessary for optimal health and normal reproduction—don’t even show up in the ONQI list: butter, organ meats, fish eggs, cod liver oil and whole raw dairy products from grass-fed cows. It would be interesting to feed one group of laboratory rats a diet of high-rated foods such as broccoli, radishes and nonfat milk, and another group of rats a diet of low-rated foods such as fried eggs, salami and bacon, and compare the results. The scale system “will allow busy parents and others who care about nutrition a quick, at-a-glance way to see what food item is ultimately the healthiest without having to read every label.”95 An ominous statement! Can we expect to see the ONQI replace food labels sometime in the future?

A news item celebrating the eighty-fifth anniversary of Frigidaire’s electric refrigerator recently listed the contents of the fridge, then and now. In 1918: a bottle of whole raw milk, eggs, lard, cream, churned butter, homemade lemonade, homemade cottage cheese, apple butter, homemade jelly, fresh meat. Today: one gallon reduced-fat ultrapasteurized and homogenized milk, eggs, fat-free margarine, flavored nondairy creamer, sports drinks, squeezable yogurt, colored ketchup, bagged salad, ice cream and frozen dinners. In other words, in 1918, Americans ate real food including plenty of animal fats; today Americans eat mostly processed food and the animal fats have largely disappeared—only eggs have survived the food Puritan finger wagging, probably because fake eggs are just too disgusting for words.

The biggest change during the last few decades is reflected in milk consumption patterns. In 1945, Americans consumed nearly forty-one gallons of whole milk per year, compared to only eight gallons per person today. Consumption of lower-fat milks was fifteen gallons in 2001, up from four gallons in 1945 and six gallons in 1970.96 The change reflects more than thirty years of constant industry propaganda against animal fats as well as greatly increased intake of soft drinks and juice, which have largely replaced milk in children’s diets. A 2002 study found that 51 percent of the average American child’s daily liquid intake is made up of sweetened beverages, which is one of the likely reasons that obesity is steadily increasing.97

However, one recent and surprising trend is a rise in butter consumption over the last few years—not by leaps and bounds, but steadily upward—both in the United States and in Europe. This shift in consumption patterns may explain a resurgence of anti–saturated fat messages in the United States and overseas.

Britain’s Food Standards Agency launched a “health” campaign in February 2009 costing over three million pounds to “raise awareness of the health risks of eating too much saturated fat,” and lamenting the fact that “the UK is currently eating 20 percent more saturated fat than UK Government recommendations.”

The highly coordinated campaign included a forty-second TV advertisement in which a “jug of saturated fat is poured down the sink, overloading and blocking a kitchen pipe to vividly bring to life the message that too much saturated fat is bad for your heart.”* Print ads encouraged Britons to cut the fat off their meat, switch to lower-fat dairy products, and use vegetable oils instead of butter when cooking.98 The campaign referred to a 2008 government report that claimed “more than 3,500 premature deaths could be avoided every year” if Britons consumed within the guideline daily amount of saturated fat.

In New Zealand, newspaper articles have urged the population to eat less bacon and sausage, avoid butter and pastries containing butter, and take children off full-fat milk after the age of two “to avoid clogging their arteries.” One university professor has even called for a tax on “poison” butter.99

What modern dietary advice has done is whiplash most Americans between two extremes—between a puritanical low-fat diet and processed pornographic food, loaded with industrial fats and oils. A diet of skinless chicken breast, dry whole grains and unbuttered vegetables is bound to create cravings, which are most often met by indulging in junk food. Americans seesaw between virtuous eating and consuming a whole Sara Lee coffee cake alone in the evening hours when the body sends powerful messages signifying hunger even though the stomach is filled.

The only solution to such chaotic eating patterns is to return to a diet that provides our bodies with the nutrients they need, including saturated animal fats and the many nutrients they contain. The prescription for what ails the American eating dysfunction is butter, egg yolks, cream, whole milk, cheese, rich pâtés, fatty meats and chicken with succulent skin.

THE EXPERTS TELL US THAT saturated fat is bad because it raises cholesterol levels. But it seems that no matter what Americans are eating, experts say our cholesterol levels are too high. Hence the push for cholesterol-lowering statin drugs, the greatest boondoggle the pharmaceutical industry has ever enjoyed. Statin drugs bring many billions dollars per year on the premise that they save lives and have few side effects.100 Are cholesterol-lowering drugs actually helping anyone other than the pharmaceutical companies?

In February 2015, the journal Expert Reviews in Clinical Pharmacology published a review article entitled, “How statistical deception created the appearance that statins are safe and effective in primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease.” Authors David M. Diamond and Uffe Ravnskov conclude that although cholesterol-lowering statin drugs effectively reduce cholesterol levels, they fail to improve heart disease outcomes; they also describe how statin advocates have used deceptive statistical manipulations to create the false appearance that cholesterol reduction results in a reduction in heart disease.

According to Ravnskov and Diamond, statin advocates use a statistical method called relative risk reduction (RRR) to misuse and manipulate the data. This method amplifies any trivial way statin drugs could possibly benefit heart disease. The authors also describe how the directors of the clinical trials on statin drugs succeeded in hiding the drugs’ significant, toxic side effects.

According to Ravnskov and Diamond, what has emerged, after thirty years of statin promotion, is the fact that these cholesterol-lowering drugs increase the risk of cancer, cataracts, dementia, diabetes and muscular-skeletal diseases—side effects that more than offset any possible, trivial benefits. In fact, in one of the most positive clinical trials on statins, researchers used statistical deceptions to transform a possible 1 percent heart benefit into a supposed 36 percent benefit through a meaningless relative risk reduction estimate. In the widely publicized JUPITER study, researchers misleadingly transformed a minuscule 1 percent benefit into a 54 percent benefit.101 A second study, published in the same journal, indicates that statins may actually cause atherosclerosis and heart failure.102

Researcher David Evans has compiled the overall mortality of participants in the thirty-three statin trials to date (2015). The difference in the percentage of people alive at the end of the trials in the carefully selected treatment groups and in the control groups (which almost always have more smokers) in all the trials is trivial. When the total number of people in each trial is taken into account, the data reveal that 0.61 percent more people were alive who were taking statins at the end of the trials than the people taking a placebo.103 The only sensible conclusion, after three decades of study, is that taking cholesterol-lowering medication will not prolong your life and may plague your later years with a number of painful and debilitating side effects.

Yet in what can only be described as nationwide insanity, statin pushers are now citing two studies as justification for putting people with “normal” cholesterol levels on statins. Millions more Americans now get prescriptions for cholesterol-lowering statin drugs because they also lower C-reactive protein (CRP), a marker for inflammation. One study is the above mentioned JUPITER study, in which the statin Crestor was said to “dramatically cut deaths, heart attacks and strokes in patients who had healthy cholesterol levels but high levels of a protein associated with heart disease.”104

In reality, the actual differences in outcome in the JUPITER study were very small, with the difference in mortality between the statin and the control groups after nearly two years only 0.25 percent; and researchers stopped the trial early, just as the projected overall mortality of the statin group was about to surpass that of the placebo group. The selection process for trial participants was so rigorous that it screened out eight of ten senior citizens recruited, for conditions like inflammatory disease and for “unstated reasons.” The stock of AstraZeneca, maker of Crestor, climbed 45 percent after JUPITER was halted.*

The second study doctors relied upon to justify statin prescriptions took place at UCLA. The study revealed that half of over one hundred thirty thousand hospital admissions for heart disease had normal levels of LDL-cholesterol—the so-called bad cholesterol. By the tortured logic of statin-numbed brains, this allowed researchers to claim that the ideal LDL level was set too high and the “majority of people would be recommended to take a statin.”105

Meanwhile, research published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences suggests that cholesterol-reducing drugs may indeed reduce brain function. According to Yeon-Kyun Shin, a biophysics professor in the department of biochemistry, biophysics and molecular biology, studies indicate that the drugs may keep the brain from making cholesterol, thereby affecting the machinery that triggers the release of neurotransmitters. “Neurotransmitters affect the data-processing and memory functions,” says Shin. “In other words, how smart you are and how well you remember things.”106 Another study found that obese men taking statins had a fifty percent increase in prostate cancer.107 Statin promoter Professor Sir Richard Peto of Oxford University dismissed the findings as a “statistical fluke.”

It is truly incredible the lengths to which scientists invested in the lipid hypothesis will go to explain away all the contradictions to their theory. They even have a creative explanation for the French paradox. According to Timo Strandberg from the University of Oulu, Finland, “Fewer coronary deaths during the 1970s and 1990s in France than in Britain (or in the US) were simply reflecting much lower saturated fat consumption and lower cholesterol levels in France during earlier decades. While saturated fat consumption started to increase in Britain from the late 19th century and reached a plateau during the 1930s, this increase did not happen in France, a Mediterranean country, until from the 1970s.”108 What are you smoking, dear Timo? Many Americans visited France in the 1970s and the 1990s and remember the pleasure of French full-cream cheeses, whipped cream, soufflés and plates swimming with butter. Even today, saturated fat consumption by the French is the highest in Europe, while rates of heart disease are the lowest.109 According to Professor Strandberg, the low levels of heart disease in France today are due to the use of cholesterol-lowering statin drugs. “Eating lots of cream cheese and butter-rich croissants may not be so dangerous if you are on a statin,” says the professor. What’s really dangerous is advice from academics so blinded by their own dogma that they cannot distinguish fact from fiction, and who continue to promote the very low-fat or wrong-fat diets that are obviously killing us.

Doctors in the United States write over two hundred fifty million prescriptions for cholesterol-lowering statin drugs per year, despite the long list of side effects: memory loss, cognitive decline, Parkinson’s disease, muscle wasting, back pain, heart failure, weakness, impotence and fatigue.110 Now another can be added to the list: diabetes. A study published in the Archives of Internal Medicine, which looked at data gleaned from the Women’s Health Initiative, found a nearly 50 percent increase in diabetes among longtime statin users.111 A 2011 analysis in the Journal of the American Medical Association112 and a 2010 analysis in The Lancet113 also found a higher risk of diabetes among those taking cholesterol-lowering drugs. Doctors may be hemming and hawing, but they continue to prescribe them. “I don’t think there’s any debate remaining, particularly in the higher doses, about whether statins slightly increase the risk of developing diabetes,” says cardiologist Steven Nissen of the Cleveland Clinic. Yet he claims that statins are “among the best drugs we’ve got.”114 Even a spokesperson for the American Diabetes Association (ADA) urges the continuation of statins. “Every medication has risks and benefits,” says Vivian Fonseca, president of the ADA, “but you don’t want people to have heart attacks because they are so worried about getting diabetes.”115

YOU CAN’T HELP BUT WONDER whether the folks involved in this tragic chain of events—from the eager beaver copywriter composing ads for Crisco, to the men in white coats who lied about the results of the Lipid Research Clinics’ trials, to the dietitian-nuns foisting low-fat diets on growing children—you can’t help but wonder whether they ever had a twinge of conscience, whether they ever heard the heart knocking softly on the back door of the brain. But as Upton Sinclair once said, “It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it.”

But achieving good health in this atmosphere of confusion does depend on understanding the fact that saturated fat and cholesterol are not dietary villains but vital factors in the human diet.