CHAPTER 5

AA and DHA

Fats from warm-blooded animals contain lots of saturated fat, but their value doesn’t stop there—they are also unique sources of a highly unsaturated fatty acid called AA (arachidonic acid). In addition, warm-blooded animals (along with seafood) provide another important unsaturated fatty acid called DHA (docosahexaenoic acid).

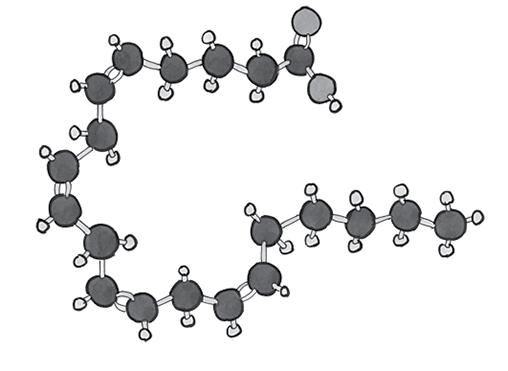

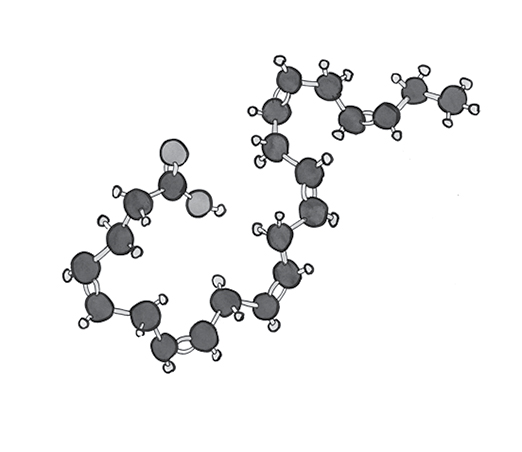

Shaped like a hairpin, AA belongs to the omega-6 family of fatty acids. It contains twenty carbons, elongated from the eighteen-carbon “parent” omega-6 molecule (linoleic acid) and desaturated from the original two double bonds to four.* Likewise DHA is a highly unsaturated “curly” molecule, which belongs to the omega-3 family and contains twenty-two carbons and six double bonds.

Arachidonic acid (AA) is an omega-6 fatty acid that contains twenty carbons and four double bonds.

DHA (docosahexaenoic acid) is an omega-3 fatty acid that contains twenty-two carbons and six double bonds.

According to Barry Sears in his popular book The Zone, arachidonic acid in food is unhealthy. AA is a precursor to the Series 2 prostaglandins or eicosanoids, which are involved in swelling, inflammation, clotting and dilation. (Prostaglandin Series 1 and Series 3 groups are said to have the opposite effect, with anti-inflammatory characteristics.) According to Sears, the Series 2 family includes “bad” eicosanoids—he warns readers against eating liver and butter, sources of arachidonic acid.1 Not only is AA inflammatory, he claims, but it “is so potent and so dangerous that when you inject it into the bloodstream of rabbits, the animals die within three minutes.”2 In fact, it is the presence of arachidonic acid in animal fats that researchers point to when they accuse animal fats of causing dangerous inflammation.

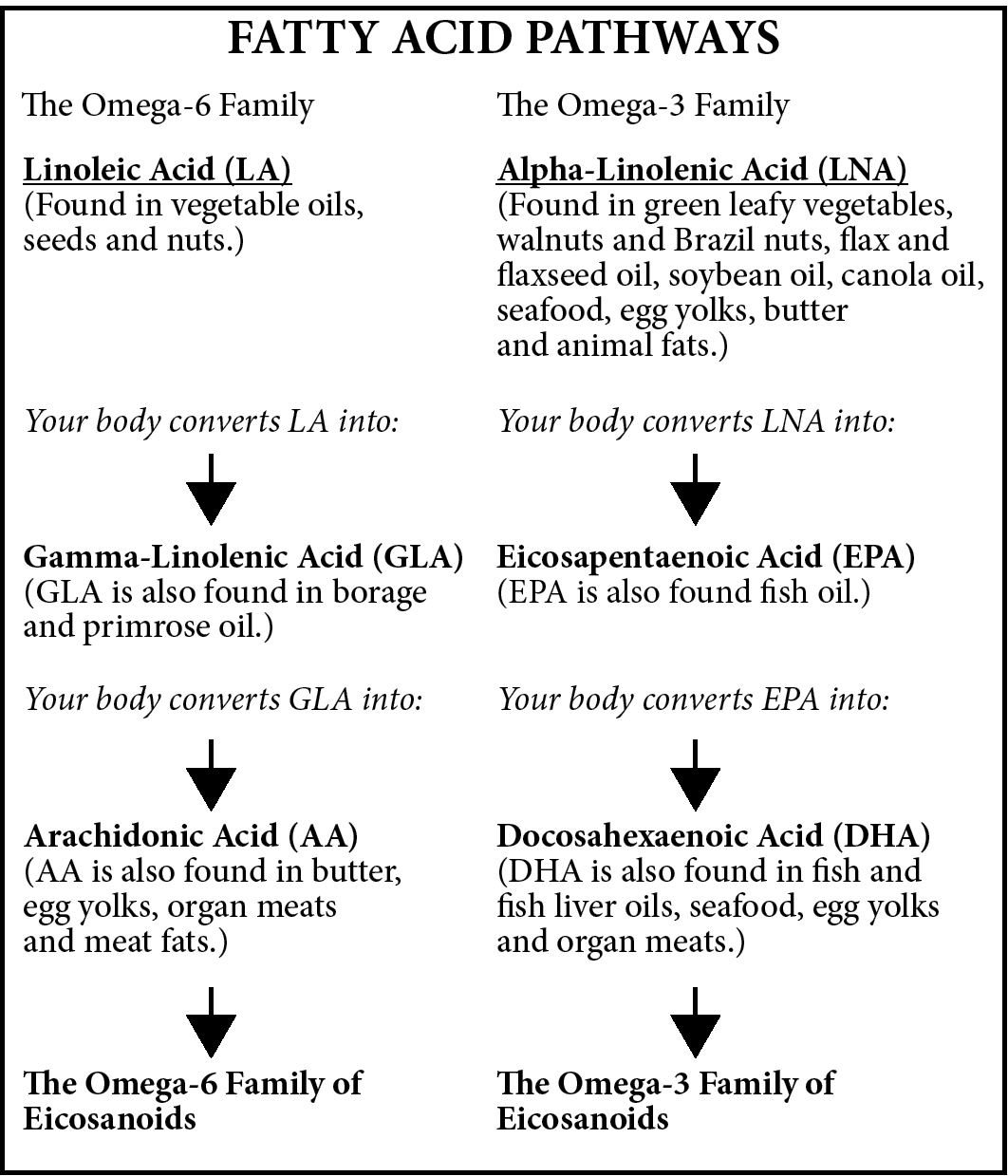

In principle, our bodies can make AA out of eighteen-carbon linoleic acid and DHA out of eighteen-carbon linolenic acid. However, many factors can interfere with this conversion, and some people even lack the enzymes to make these changes. Our best option is to obtain AA and DHA from food.

Fortunately, humans and animals get the AA they need by eating food or by making it, not by injecting it into the bloodstream. And to say that AA is inflammatory represents a simplistic view of the complex interactions that create inflammation in the body—a process, by the way, that is highly necessary for our survival.* Like all systems in the body, the many eicosanoids work together in an array of loops and feedback mechanisms of infinite complexity. AA is pro-inflammatory in situations requiring inflammation and anti-inflammatory in situations requiring suppression of inflammation.

Arachidonic acid deficiency actually produces a number of inflammatory symptoms, including dandruff, hair loss, infertility and irritated, red, sore, swollen and scaly skin.3 Over-the-counter nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) work by inhibiting supposedly “inflammatory” compounds made from arachidonic acid, ironically with several inflammatory side effects. One side effect is intestinal pathologies, which closely resemble celiac disease in laboratory animals when given gluten or even egg white,4 and they interfere with the resolution of autoimmune conditions.5

Our bodies can make AA from the “parent” omega-6 fatty acid, but we do so slowly and inefficiently, and in many circumstances—nutrient deficiencies, malnutrition, diabetes, low thyroid function, genetic defects—we cannot make it at all. In these common situations, arachidonic acid is “essential,” meaning that we must get it from food. Egg yolk—especially duck egg yolk—and liver are our best sources of AA, followed by butter and meat fats like lard—all “forbidden” in government dietary guidelines.6 AA occurs in most meats—probably as a component of the cell membrane—and also in seafoods. Poultry and poultry fat are excellent sources, with highest levels most probably in duck and goose fat.

Arachidonic acid is an important constituent of cell membranes, particularly abundant in the brain, muscles and liver. It is involved in cellular signaling and is necessary for the repair and growth of skeletal muscle. Thus, body builders have high requirements for AA, as do pregnant and lactating women, infants and growing children. Higher concentrations of AA in muscle tissue may also be correlated with improved insulin sensitivity.7

A key role of this maligned fatty acid is the formation of tight cell-to-cell junctions in the skin and intestinal tract, which can then act as physical barriers against toxins and pathogens.8 It is AA in the cells lining the gut that allows our immune system to react to food proteins with tolerance instead of mounting an immune response,9 and to make important molecules called lipoxins that help resolve existing inflammation.10 It’s no wonder that we are seeing so many food intolerances in our fat-phobic era, as children brought up on low-fat diets, and adults avoiding animal fats do not have the basic material they need to create a healthy, impervious gut wall. Without arachidonic acid, the gut wall can become leaky—and so can our skin. Without tight cell-to-cell junctures, the skin loses water and becomes dry and flaky. Our skin needs many compounds to be healthy, but one of the most important for glowing, buttery skin is AA.

Arachidonic acid is one of the most abundant fatty acids in the brain, and is present in similar quantities to its omega-3 cousin docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). The two molecules account for approximately 20 percent of the brain’s fatty acid content.11 Neurological health requires sufficient levels of both DHA and AA. Among other things, arachidonic acid helps to maintain cell membrane fluidity in the hippocampus, the seat of memory formation.12 It works to protect the brain from oxidative stress13 and also activates a protein involved in the growth and repair of neurons.14

Bodybuilders know about AA, often taking it as a supplement. A placebo-controlled study found that supplementation of arachidonic acid (1,500 milligrams per day for eight weeks) increased lean body mass, strength and anaerobic power in experienced resistance-trained men.15 Another study found that 1,000 milligrams per day of arachidonic acid for fifty days enhanced anaerobic capacity and performance in exercising men.*16

We know that omega-3 fatty acids can protect us against heart disease, but so can omega-6 AA. A meta-analysis by Cambridge University looking for associations between heart disease risk and individual fatty acids reported a significantly reduced risk of heart disease with higher levels of omega-3 EPA (eicosapentaenoic acid) and DHA, but also with omega-6 AA.17

As mentioned, key signs of AA deficiency include dry, scaly, itchy skin, hair loss and dandruff, but these often clear up easily by eating good fats like butter and egg yolks. Other consequences of AA deficiency include reproductive difficulties, digestive disturbances, food intolerances, kidney disease, inability to maintain weight, poor immunity and poor growth in children. Ironically, even though AA is considered “inflammatory,” deficiency can result in inflammation.18

What’s clear is the fact that the demonized fats like butter, egg yolks, poultry fat and lard supply vital factors like AA for growth and health—conventional dietary advice has led health seekers down the wrong road!

UNLIKE THE LESSER-KNOWN ARACHIDONIC ACID, DHA is almost a household word. Popular wisdom rightly values DHA for brain function.

As with AA, our bodies can, in principle, make DHA from the eighteen-carbon omega-3 fatty acid. But in practice, this is a slow and inefficient process, and many people lack the enzymes needed to elongate and desaturate the parent molecule. These “obligate carnivores” must obtain their DHA fully formed from seafood, as well as from organ meats, egg yolks and animal fats like butter.19 Babies get DHA from mother’s milk, which ranges from a trace (0.07 percent) to greater than 1 percent, depending on the mother’s diet.20 A growing body of research indicates that DHA in the diet of infants and growing children contributes to optimal neurological development and keen vision.21

DHA serves as a primary structural component of the human brain, cerebral cortex, skin, sperm, testicles and retina. DHA deficiency is associated with cognitive decline22 and depression—the brain tissue of severely depressed patients often shows reduced DHA levels.23 Other studies have indicated that DHA benefits a range of nervous system functions, cardiovascular health and potentially other organs; supplements may be of benefit for stroke victims. DHA appears important in the formation of the acrosome, an arc-like structure on the top of sperm, which is critical in fertilization because it houses a variety of enzymes that sperm use to penetrate an egg.24

While skin problems, digestive disorders and food intolerances can indicate AA deficiency, DHA deficiency manifests primarily as neurological disorders including numbness and tingling, weakness, pain, psychological disturbances, poor cognitive function and difficulty learning. Other signs of deficiency include poor visual acuity, blurred vision, poor immunity, poor growth and inflammation.25 Our tissues use DHA to synthesize compounds called “resolvins,” which help bring inflammation to an end when it is no longer needed.26 A number of investigators have postulated that DHA deficiency may be a major cause of widespread declines in cognitive function, increases in mental disorders and epidemic levels of degenerative disease.

MANY OF US ARE ALREADY familiar with the concept of balancing omega-6 and omega-3 fatty acids in the diet. The modern diet contains about twenty times more omega-6 than omega-3, whereas the ratio should be more like two or three to one. Of even more importance is a balance of the elongated and desaturated versions of omega-6 and omega-3: AA and DHA. Too much of one will result in deficiency symptoms of the other. In addition, too much EPA, the other common elongated omega-3 fatty acid, found mostly in seafood and fish oil supplements, can result in deficiency symptoms of both AA and DHA.

Vegetarians and vegans have substantially lower levels of DHA in their bodies,27 and often resort to fish oil supplements to correct the imbalance. Unfortunately, short-term supplemental fish oils have been shown to increase EPA, but not DHA. In addition, such supplementation leads to decreased levels of AA.28 It isn’t a long-term solution.

Our bodies use the same enzymes to convert the parent omega-3 fatty acid to DHA as they use to convert the parent omega-6 fatty acid to AA. An excess of one precursor can therefore outcompete the other for the enzymatic machinery. Large amounts of either parent omega-6 or omega-3—from the consumption of vegetable oils (high in omega-6), flax oil (high in omega-3) or even fish oil (high in EPA) will cause the cell to make fewer of these enzymes, resulting in deficiencies of either AA or DHA.29

This competition and cellular confusion can be avoided altogether by providing small amounts of preformed AA and DHA through the diet—and the key point is that these come from animal fats: egg yolks, organ meats, butter, animal fats, fatty fish and small amounts of cod liver oil or shark liver oil. Avoiding polyunsaturated vegetable oils and including adequate saturated fat in the diet will ensure that these highly unsaturated fatty acids are protected from oxidation and incorporated and preserved in the body. Other dietary factors that ensure the right balance of DHA and AA include avoiding refined sugar, consuming adequate calories and protein and plentiful intake of vitamin B6, biotin, calcium, magnesium and fresh, whole foods abundant in natural antioxidants. Deficiencies of DHA and AA are commonly linked with alcoholism, diabetes, insulin resistance, certain genetic variations and strict vegetarianism.30 Liberal amounts of egg yolks, butter and liver containing preformed arachidonic acid provide protection against the adverse effects of too much EPA (often the result of taking lots of fish oil supplements). The key is balancing nutrient-dense foods from land and sea—organ meats, egg yolks and animal fats like butter for AA, which nourishes the skin and digestive tract, and seafood, including small amounts of cod liver oil, for DHA, which nourishes the nervous system, the brain and the eyes.

Unfortunately, current dietary advice urges people to eat “good” polyunsaturated oils (soybean, corn, safflower, canola, olive and sunflower) along with supplements of fish oil. “Fats found in fish and plants may help older adults liver longer,” say the headlines.31 This combination is a recipe for deficiencies of both AA and DHA since the omega-6 fatty acids in vegetable oils and the EPA in fish oil can interfere with the body’s own production of AA and DHA.

IN THE EARLY 1980s, NASA sponsored scientific research to find a plant-based source of DHA for long-duration space flights. The researchers discovered that certain species of marine algae could produce an oil that contains both DHA and AA (sometimes called ARA).32 These plant-derived, industrially produced versions are used in many DHA and AA supplements, and they are also added to baby formula. A number of studies have found problems with the algae-derived supplements, such as digestive disorders and neurological problems including hearing loss, with no real benefit to growing infants.33 Nurses have described infant formula to which manufactured AA has been added as the “diarrhea formula,” and the FDA has received hundreds of reports of adverse reactions in babies.34 Women given DHA derived from egg yolks had higher levels of DHA in their milk than mothers given DHA derived from algae.35 The plant-based AA and DHA are extracted with toxic hexane, and traces always remain in the product.36 And it is highly likely that the industrially processed versions of these fragile fatty acids are highly oxidized—in other words, rancid.

This is just one of many examples in which plant-based or plant-derived substitutes for animal products fail to make the grade. It remains much better—and much more fun—to get the AA and DHA we need from delicious animal foods like pâté and caviar. In fact, many delicious traditional food combinations provide the synergistic combination of DHA from the omega-3 family with AA from the omega-6 family: lox and cream cheese, caviar and sour cream, liver and bacon, salmon with béarnaise sauce, and Welsh rarebit made with egg yolks and cream. Such foods not only taste delicious; they also nourish the body and mind.