Photographic images of pet or companion animals, especially in a modernist fine art context, are often seen as nostalgic or sentimental. The animal’s presence is usually highly scripted: formally arranged in the image, the animal frequently stands as a metaphor for human behavior, as an indicator of class or economic status, or as a symbol of its role as commodity item (see Baker 2001; Schlosser 2007). For many postmodern artists, pets are somehow “less than” wild animals, having given up their independence to rely on humans for their care (Baker 2000:168–169). This disparaging view within the fine arts emerges in part from ambivalence within the pet-keeping population itself. Even though pet keeping in many Western cultures is at an all-time high, and people claim that they value their pets highly and consider them as friends (Olmert 2009:242), they still often maintain an inherent prejudice, which intimates that living with and loving a pet animal is a shameful substitute for “real” or more legitimate human relationships (Levinson 1972:168; Serpell 1986:vix).

This chapter looks at the work of four women artists, all working with photographic media, whose art focuses on relationships with pet or companion animals: Martha Casanave, Barbara Dover, Carolee Schneemann, and myself. All four have chosen to include touch as an aspect of their exploration of their relationships with companion animals. Made in a deliberate and sometimes provocative manner, this choice of subject matter places them in danger of being disenfranchised in both the art and academic worlds. The choice of the domestic setting as the backdrop for their artworks, the societal association of touch with nurturance and play, and an open acknowledgment of their relationship with a pet animal have exposed these artists to the criticism of unacceptable subject matter for “serious” artists.1 Casanave, Schneemann, and myself add another complexity to the picture: We are both subject and object of our work. A photographer who chooses to photograph herself along with her pet cannot retreat safely behind the lens of her camera to manipulate the image of her subject. Instead she must grapple with the logistics of taking the picture from that awkward vantage point, giving up a measure of control in the art-making process. She also appears in front of the camera as a coequal with the animal.

Touch is an often overlooked but nonetheless crucial aspect of human-animal relationships as well as a way to express that relationship in a visual art context. Circumventing both the one-sided activity of conveying information via language, which the animal is unable to reciprocate, and the act of looking from a privileged distance, touch is instead potentially more reciprocal. It brings human and animal into physical proximity and can compel further contact. Touch by a human hand often allows both to move into a more equal eye-level view, one with the other. An unconstrained animal is free to touch back or not by her choice, and a touch provides both participants with a reciprocal exchange of visceral or embodied information about the other (Weber 1990:24–25; see also Merleau-Ponty 1962 [1945]), a felt-sense that often functions outside the patterns of language. Animals can perceive information in many different ways than we do, so the type of information exchanged through touch may be particular to each party. Touch allows for a further articulation of the physical and psychological presence of each member of the partnership. Recently, when I cupped my hand momentarily around the stomach of a pregnant cat, my entire perception of her experience was instantly altered through the information conveyed from the sensation of the hot, strangely prickly, curiously alive movement of her belly.

The human touching an animal is privy to many types of information, including data about temperament and health. I frequently touch my animals’ ears for a quick check of their temperature, feel for a scratchy coat, which would indicate a loss of health, or pick them up to get an approximate sense of their weight gain or loss. However, this type of touch “functions more like sight (i.e. cognitively) … and need not entail closeness or reciprocity” (Weber 1990:25; see also Wyschograd 1981). This cognitive touch can even have a distancing function, a way of “mastering experience and appropriating it” (Weber 1990:25). The type of touch that allows familiarity and a growing sense of the other’s mind must be more reciprocal. Polly Ullrich (1996–1997) observes a trend toward the importance of such touch in contemporary artwork. Applying the theories of phenomenologists such as Maurice Merleau-Ponty to the work of a group of postmodern artists, she foregrounds the reciprocality of touch, noting that “the most singular characteristic of touch is that in touching, one is touched in return” (p. 13). Ullrich further emphasizes the importance of these tangible affiliations by saying, “Touch implies mutuality, not dominance” (p. 13). Touch—mutual and consensual in particular—provides a unique perceptual opportunity for both participants to experience each other.

Touch has been disparaged within philosophical and artistic discourses (see Weber 1990; Candlin 2006; Perricone 2007). Philosopher Renée Weber (1990) remarks, “Touch as an interactional modality has been neglected by philosophy. Especially in the last three hundred years, since the time of Descartes, only mental and verbal exchanges have been considered important” (p. 13). The tactile is somehow “less than” the visual and the auditory. Artist and museum studies lecturer Fiona Candlin (2006) argues that we need to reassess the pejorative role that touch has been accorded in the recent historiography of art in light of contemporary museum practice that emphasizes touch. She writes “We do not pass through touch to reach vision. … Once we start thinking about vision and touch as being intimately related then correlative equations of touch with body and not mind, nature and not culture, the past and not present, become equally untenable” (p. 150). Candlin urges readers to “avoid thinking of vision as being more conceptual than touch,” and reminds us to “ask how touch and the tactile qualities can lead an audience into a discussion of content” and how they can “generate meaning” (p. 152). Although not intended as such, Candlin’s points are quite helpful for a discussion of the ways that photographs of animals and humans touching can generate meaning for the viewer about animal subjectivity.

Traditional photographic representations of pet animals often convey no sense of the vibrant self-directedness and agency of the animal subjects their human companions witness on a daily basis. Traditional photographic images of pets reflect the view that animals, because they lack language, have no “voices.” The act of touch provides a unique way to dislocate the assumption that lack of language means an incapacity for agency. By introducing an avenue through which human and animal interact, that is, the sensory experience of touch, the photographer can enable the animal to exhibit a similar sense of subjectivity to that of the other subject in the frame, the human.

Photographs also pull viewers in via their own viscerally imaginal involvement. Meg Daly Olmert (2009) researches the social bonding mechanisms between humans and animals. “From day one, all social mammals learn that the warmth and touch of another is good” (p. 31). She comments later, “We and other mammals have a common social biology that allows us to approach, interact, and relax in each other’s company” (p. 220). The release of the hormone oxytocin accompanies and facilitates the bonding both between a mother and child who are touching, and between humans and companion animals. Simply viewing photographs of a subject interacting with another activates the same release of oxytocin that would be triggered by an actual interaction. Olmert notes, “Brain researchers … used fMRI imaging to see what goes on in a mother’s head when she’s looking at her baby. In their study, they don’t even have the mother look at her actual child but merely a photo of the baby. ‘Just watching’ the image of her child was enough to trigger a powerful response in brain cells loaded with oxytocin” (p. 30).

Intimate touching involves an exchange between the parties, and it cements and enriches relationships in reciprocal but difficult to fully articulate ways. Olmert writes, “Mutual touch still raises and lowers our body temperature, speeds up the healing of wounds, takes away physical and emotional pain, and often is the only way we can communicate deep feelings for which there are no words” (p. 227). Weber explores the history of the philosophical analysis of the sense of touch and in the process develops three models of touch. For her, “the most comprehensive model,” the one that not only incorporates touch as tactile stimulation or direct contact but also serves as a method of “‘reaching’ the other at some level deeper than the visible and behavioral one,” is the “field model” (1990:14). Weber begins her discussion by announcing, “My focus is … holistic. It deals with the touch of a person and person, or of person and animal—but not the touch of hand and skin, or hand and fur, nor the idea of tactile stimulation” (p. 11). For Weber, a more thoughtful analysis leads away from the idea that touch functions simply as a physiological conduit streaming information in one direction from an exterior entity. Instead it becomes a mutual, participatory action that offers two beings nuanced perceptions of the other, affirming their intrinsic relatedness and providing solace and comfort. Weber continues by explaining that the holistic field model is based on the “underlying assumption of Eastern thought. At some deep level in virtually all the Eastern metaphysics, we are all interdependent and interconnected. We’re actually not separate entities” (p. 40).

Philosopher Christopher Perricone (2007) uses art historian Bernard Berenson’s ideas about the connection between touch and the aesthetic value of art-historical masterpieces—what Berenson calls “tactile values”—as a stepping-off point for his further articulation of the deeply embodied, intrinsic, but often overlooked place that touch holds for viewers who are integrating information about artwork. For Berenson, as viewers our “tactile imagination” is stimulated when an image maker is able to activate our sense of touch or tactile sense, and this provides a “quality of life-likeness” or “material significance” to our “retinal impressions” (Perricone 2007:91). For Perricone, the ways that we know artwork and the ways that we know each other are both intimate and associated with touch and with our “animal nature” (p. 96). Like Olmert, Weber, and others who are profoundly concerned with articulating this sensation, Perricone understands touch as communicating something deeper than language or sight. “There is a ‘knowledge’ communicated through the body that produces a person’s healthy development as well as builds friendship and trust between one person and another. Knowledge of the most profound and intimate emotions is literally conveyed by touch” (p. 96).

Although Perricone’s research deals with the tactile qualities of artwork and not with the ways that humans come to know animals through touch or photographs of touch, his article pulls together important ideas for understanding the ways that physical contact conveys meaning to viewers of contemporary photography. For social mammals like humans and domesticated animals, social bonding, facilitated by mutual grooming (petting your cat, who then licks you), plays a crucial role in the formation of relationships (see Olmert 2009). The photographs discussed in this chapter are in a unique position to activate the tactile imagination given their use of touch as a bridge from animal bodies to human bodies. According to Perricone (2007), “Chances are the tactile imagination is inspired most, given the allocation of brain space and the density of receptors, by what the hand touches” (p. 92). And, for the artists in this chapter, what the hand touches is the animal next to it.

Martha Casanave: Beware of Dog

In the book Beware of Dog California-based photographer Martha Casanave (2002) recorded her interactions with her pet whippet in her home. The images are black and white and are beautifully shot with lush natural lighting. In the introduction to the book, Casanave’s written description of the dog and their life together is heavily grounded in perceptual descriptions of the dog and the dog’s behavior, e.g. “My dog always smells what’s different about me” (p. 9). At the same time, she also speaks about the limitations of the sensory information that a black and white photograph can convey to a viewer. She lists nuanced perceptual information about the dog she feels cannot be conveyed by the sight of a photograph, including smells, sounds and the feeling of touch, e.g., “the velvety feel of a whippet’s belly skin” (p. 7). However, in the next paragraph she describes how the activity of photographing the dog—“the process of paying close attention to every detail of my dog and watching her behavior closely”—became (almost) more important than the photographs produced by this activity (p. 8). I argue that for Casanave the process of paying such close attention to the whippet allowed her to develop photographic strategies or tropes that, in contrast with her stated repudiation, do allow the viewer to experience an embodied tactility or felt-sense of the dog.

Instead of conforming to established conventions for photographing pets, the artist produces images that reflect intrinsic characteristics of the animal. Casanave notes that the nature of the whippet is to alternate between periods of quietude and then intense activity: “indolence and exuberance” (p. 8), and the two discrete photographic strategies that she develops to photograph the dog reflect these modes. Only one employs touch between herself and the animal, but both utilize a visceral, embodied connection that transfers information about the animal to the viewer of the photograph. Cleverly exploiting the inherent materiality of black and white film, Casanave uses motion blur to illustrate one aspect of the animal’s persona: grainy swirls of silver trace the whippet’s rapid bursts of frantic motion, conveying to the viewer a visceral sense of the dog’s action. The dog is shown running or chasing a ball, full body, oscillating against the wide expanse of a backyard lawn and fence in streaky motion (figure 2.1). Then, in contrast with the first technique, but still communicating with the viewer through the felt-senses, the artist uses elegant, tightly composed, focused and lit images to convey the dog’s complementary moments of stasis. Photographed inside Casanave’s house, the home being the frequent site of human-companion animal encounters, the shots of the dog at rest often include the artist in contact with the animal. The artist captures minor, mundane, almost trivial moments of intimacy between dog and person, asleep, napping during the day on a sofa or bed. The tight spaces, sharp focus, accentuating the details of the dog’s coat, bony spine, nails, and whiskers, and shallow depth of field combine with the minimal background detail of the images to invite the viewer to engage with the small moments of intimacy that exist between the two.

FIGURE 2.1. Martha Casanave, “Untitled,” from Beware of Dog. Carmel, CA: Center for Photographic Art, 2002. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Although in the preface to her book Casanave writes in almost painfully tender detail about aspects of their life together, she does not refer to the dog by name. In somewhat similar fashion, she excludes her own face from the photographs, crops her body close enough that it remains relatively gender-neutral, and often fragments the dog’s face and body as well. These tropes provide a visual context for the viewer to encounter the dog with a sense of parity to the human, an unusual situation for many pet photographs. By including herself in the photographs along with the dog, Casanave is similarly unable to maintain the typical unequal power relationship formed between artist and model, in which the artist is in complete control of her subject’s representation.

In addition to creating a sense of visual equality or correspondence in the frame of the photograph, the implied motion, based on touch, generated by the pair’s actions toward each other allow the viewer to respond in an embodied fashion. In one photograph Casanave appears to measure the dog’s paw, comparing it with her own hand (figure 2.2). In other photographs she gently wiggles the bones in the dog’s leg, strokes her smooth face, and cups her muzzle between her forefinger and thumb, all gestures of intimate and equalizing familiarity. The viewer can imagine Casanave exploring the dog’s body, absorbing embodied knowledge about the animal, enjoying the tactile sensations of her fur, tail, tendons, and the pads of her feet, and can experience the haptic sensations Casanave feels and transmits through her human presence in the photographs.

FIGURE 2.2. Martha Casanave, “Untitled,” from Beware of Dog. Carmel, CA: Center for Photographic Art, 2002. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Casanave’s trope of fragmenting her human and animal subjects creates meaning in the images in a number of provocative ways. The close-up, gender-neutral limbs of the dog and human subject provide a certain anonymity and thus allow the photographs to function as images about the relationship of human and companion animals, exploring ideas that are limited not just to this particular pair of subjects. In addition, the fragmentation of the bodies allows the artist to circumvent certain neotenous or nostalgic associations with photographs of pet animals in a vernacular context. In the images in which Casanave moves in close to her subjects and crops their bodies, the resulting abstraction of the forms creates a particular synchronicity for the viewer. In one image from the book, the close-cropped round of the whippet’s back so closely mimics the curve of a human shoulder as to provide a visceral jolt of surprise when the viewer realizes the form is canine and not human. This technique creates a way for the viewer of the images to enter the space of the photograph by encouraging a kinesthetic merging with the fragmented bodies in the photographs. The fragmented limbs in the image can, in effect, fuse with the viewers’ own and allow viewers to submerge themselves in the pair’s insular world without unnecessary distraction. Casanave’s images invite the viewer to focus on intimate details of the dog and human bodies and participate in the feeling of the larger wholeness of a composite human-dog being. Although perhaps counterintuitive given the fracturing of the bodies, this fragmentation and subsequent remerging ultimately give visual form to Weber’s field model of touch and its underlying assumptions about the interconnected, inseparable nature of the physical universe and its inhabitants (1990:14).

In an untitled image from the book, the sleeping whippet enfolds Casanave’s crossed leg with her own body, upturned head resting gently against her knee (figure 2.3). Often the assumption about this type of casual physical intimacy is that it is reserved exclusively for select groups of human counterparts. For example, in the book The Caring Touch, authors Pratt and Mason note: “In our society, actual physical contact as a full and free expression of intimacy is seen to occur only in two groups of people—between mothers and children and between lovers” (1981:4). Pratt and Mason point out that touch is perhaps the only form of sensory exchange that “requires some kind of contract [agreement] between the parties concerned” (p. 3). They also suggest that intimate body contact is the “starting point of all loving relationships” (p. 4). Although the contact is between human and nonhuman animal, and not human and human as Pratt and Mason presume, Casanave and her dog have established this type of contract, and, for them, touch manifests as an expression of love and care. The images create an extraordinary sense of human and nonhuman animal together in embodied physicality, beyond the place where language is necessary. Images such as Casanave’s, which implicitly value human and pet equally, help provide a framework for the articulation of ideas about our mutual importance and interrelatedness or, in the words of Alice Kuzniar, “reciprocity and a kind of intercorporeality” (Kuzniar 2006:126), which is so vital to many pet owners today.2

FIGURE 2.3. Martha Casanave, “Untitled,” from Beware of Dog. Carmel, CA: Center for Photographic Art, 2002. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Barbara Dover: Face to Face

In Face to Face, a 2007 mixed-media installation and photographic series, Australia-based artist Barbara Dover creates photographic renderings of dyads of human and nonhuman animals. Dover (2007b) writes about human relationships with pets in a way that is reminiscent of Renée Weber’s ideas of relatedness, emphasizing “interdependent and interconnected” natures (1990:40). However, where Weber underscores touch rather than vision as the sense that activates this mutuality, Dover prioritizes the gaze—not our gaze at the animal, but a mutual gaze returned and completed by the eyes of the pet. In her photographs of people and their pets, Dover attempts to demonstrate reciprocal eye contact between the participants. Human and animals lay, sit, or stand comfortably together, situated in close proximity, one casually touching the other. However, it is touch rather than a gaze that provides a more or less constant point of contact; more often than not the gaze between human and animal is interrupted in some way, as when one of the participants turns his head or alters position. Certainly for the viewer, who may not even be able to see the eye contact between the two because of the camera angle, the perceptual link is maintained not by sight but by touch.

Arranged in a grid system, her large-scale black and white images are accompanied by objects and drawings on transparent tracing paper overlaying various sections of the photographs. Conceptually layered throughout Dover’s images are ideas about the emotion, self-awareness, and sentience embodied by the animals and transmitted to the humans through the locus of their contact. The objects she includes provide a physical manifestation of her conceptual constructs by reinforcing ideas about relatedness and further enhancing the haptic quality of the images. The tracing paper drapes against the photographs, and the other objects, often extremely tactile in nature, are piled and stacked together and then further joined with lengths of twine or ribbon. For many of the Face to Face images, Dover presents the human-animal pairs in series of sequential photographs. The settings for the photographs are domestic: bedrooms, suburban backyards or decks, or, in the case of the horses, exterior landscapes with trees. The moments the artist captures are quiet, transitory, and private. The photographs demonstrate the sense of camaraderie and ease that exists between the two figures, and, in many ways, they overtly refuse the conventions that have been established in the history of pet photography. None of the figures is highly posed. Unlike conventional pet photography, which requires the animal to mug for the camera, neither human nor pet appears overly conscious of the camera at all. Filmic in nature, the serial imagery enables viewers to see the pairs interacting over time. Their responses—humorous, playful, whimsical, or warm—are conveyed to the viewer both by facial expressions and by the gentle, mutual, consensual nature of the touch, which activates the viewer’s tactile imagination and allows her to share in the palpable, tangible connections between the two participants.

Other photographs in the series are large-scale, full-body representations of human and companion animals looking each other in the eyes. In these cases the artist floats the figures on a white background, removing any surrounding distractions, and allows the viewer to feel as if he is witnessing the private interaction between the figures (figure 2.4). Unlike Casanave, Dover includes the faces of both her subjects; and in the large-scale single images she titles the photographs with the subjects’ names. Thus, although we have less information about each pair than Casanave provides to us about herself and her whippet, we are given images that are much more specific in nature: specific to a particular human-animal dyad and to a particular incident of contact. The photographs are approximately life size, and Dover provides access to a felt-sense or visceral quality through the tactility of the objects she includes with the photographs. In (face to face) entwined the girl and the horse appear on eye level, taking up equal shares of the frame, and look as if they are playfully nuzzling each other back and forth (figure 2.5). Nestled together on the floor in front of the photographs are long bundles of human and horse hair. The objects extend the installation into the physical space of the gallery and link the viewer to the tactility of the action taking place in the photographs above, just as the tracing paper loops off the wall linking the photographs to the bundles of hair. The bundles extend Weber’s “reach” from a simple touch to an entwined relatedness, binding horse and girl together metaphorically as well as physically.

FIGURE 2.4. Barbara Dover, (face to face) Taku and Victoria, 2007. Giclee print, pencil, 1120 x 1800 mm. www.barbaradover.com.

FIGURE 2.5. Barbara Dover, (face to face) entwined, 2007. Giclee print, tracing paper, pencil, human hair, synthetic hair, horse hair, 1800 x 1120 x 700 mm. www.barbaradover.com.

FIGURE 2.6. Barbara Dover, (face to face) Betty and Julie—heart to heart, 2007. Giclee print, tracing paper, pencil, 1800 x 1120 mm.www.barbaradover.com.

In (face to face) Betty and Julie—heart to heart a cat lies across a woman’s chest (figure 2.6). The viewer encounters the visceral sense of the weight of the cat on the woman’s chest. The proximity between cat and woman, the fact that the cat is clearly comfortable enough to stay on the woman’s chest for a protracted period of time with the photographer present, the smile on the face of the woman, and the body language of the cat all indicate a sense of ease, comfort, and reciprocal trust between human and companion animal. Thus the artist shares with the viewer intimate, private moments of contact between the animal and human that would normally not be available to an outsider.

In this series Dover locates in her art making a concern for human-animal relationships and “the moral responsibility we have for animals” (2007b:2), especially for companion animals, and is insistent that the visual strategies she employs be reflective of that sense of responsibility. “The essence of such mutuality, sharing, participation and connection creates a context of care and responsibility, a context appropriate to the visual exploration of the animal-human relationship” (Dover 2007a:22). Dover foregrounds in her work the conviction that relationships she depicts between animals and humans are “unmistakably reciprocal and participatory between the animal and human” (p. 22). We might again turn to Renée Weber to explicate Dover’s intentions. Weber’s philosophy of touch borrows philosopher Martin Buber’s distinction between an I-Thou and an I-It way of relating to others (pp. 26–27). Weber links the I-It mode of interacting physically with another being to “manipulation and handling,” while the I-Thou mode corresponds to touch in the holistic sense of “acceptance and mutuality. It is a living relationship, with its own dimensions of space and time” (p. 26). In the Face to Face series, Barbara Dover creates a space for the human-animal pairs she photographs to demonstrate their mutuality and connection.

Carolee Schneemann: Infinity Kisses

While pioneering feminist performance artist Carolee Schneemann has incorporated cats into her artwork since the 1960s, two bodies of work, Infinity Kisses I and Infinity Kisses II, in which she photographically documented her interactions with two cats, have gained her particular notoriety. During the 1980s and ’90s, both her cats, Cluny and Vesper, woke Schneemann daily with extended periods of licking her lips and mouth. While Schneemann shocks viewers with the transgressive content of the images, she nonetheless opens up a new avenue for artists and viewers alike who are investigating animal psychology. Circumventing language altogether, Schneemann’s photographs privilege the exploration of actions of touch initiated by the animals. These actions, recorded photographically, are experienced by the viewer through powerful sensory experiences of their own. Encountering the images, viewers involuntarily feel the cat licking the inside of their own mouths.

Schneemann kept a 35mm film camera next to her bed and photographed the cats and herself. She held the camera out without looking through the lens finder to include the two of them, and so the framing of the shots is variable and somewhat arbitrary (Schneemann 2002:264). Schneemann displays the photographs in the form of a grid of images, and in 2008 produced a short movie that juxtaposes the 35mm images with enlarged details of the photographs (figure 2.7). Each cat appears on top of the artist, straddling her chest with his paws; both usually have their eyes closed, and saliva runs down Schneemann’s chin at times. Schneemann’s nightclothes and the pattern of her bedsheets vary from image to image, and for the most part Cluny and then Vesper appear to take the place of a human lover. Schneemann was accused of bestiality and obscenity with this work, and certainly she allows her cats to act in a manner that is outside of generally accepted social bounds (Weintraub 1998:133). However, Schneemann accepts the actions of the cats and, in fact, welcomes them as indicative of the close interspecies bond she felt with both Cluny and Vesper (Weintraub 1998:130, 133). By doing so, Schneeman refuses to negate the part her cat is playing in directing certain aspects of their relationship, as she would have had she disallowed the cat’s unconventional behavior (unconventional from a human standpoint). Schneemann says, “The cat is an invocation, a sacred being, profoundly devoted to communicating love and physical devotion, and the cat is self-directed” (2002:215).

For Schneemann’s work, touch must be contextualized within her forty-year career as a feminist performance artist, a career in which the corporeal and the tactile have played highly significant roles and within which Schneemann has situated her relationships with her cat companions (Schneemann 2002:10). She credits the inspiration for her first performance piece to her cat Kitch (Schneemann 1997:7), and has incorporated cats as part of her performance pieces and films since that time. Schneemann uses the tactile, the corporeal to tell her stories, to convey her ideas. Because language separates human and animals, she has always been open to modes of communication that replace language: psychic connections, messages in dreams, corporeal and sensual transfers of mental or emotional content (Schneemann 2002:273, 279). The taboo has been part of the ground Schneemann has worked since her career began, and from the first her cats have been part of her creative milieu, as has her sexuality.

FIGURE 2.7. Carolee Schneemann, “Infinity Kisses—The Movie,” 2008. Video still from self-shot photographic series. Copyright © Carolee Schneemann.

Julia Schlosser: Contact

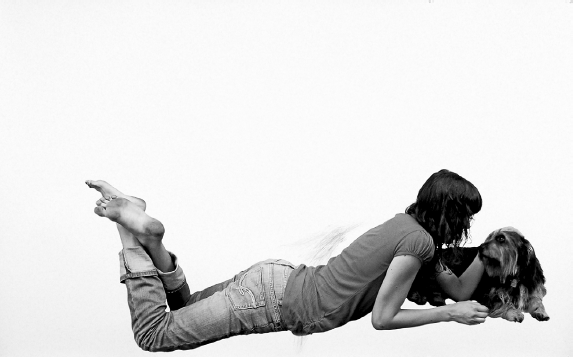

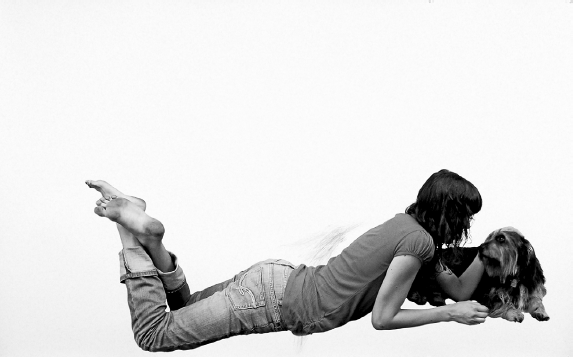

I end this chapter with a discussion of a body of my own photographic work, which, like that of the artists previously discussed, explores the complex relationships between pets and humans in the space of the home, both my home and those of others. In the series Contact I investigate the nature of touch as it occurs between human and companion animals on a daily basis (figure 2.8). This kind of touch often takes place in the course of daily tending activities. As people feed, groom, play with, or move their animals from one location to the next, they frequently exchange mutual contact, developing daily patterns of habitual interaction. Because I was interested in the transient touch connections that happen many times daily, such as a pat on the head, rub on the leg, or stroke of the tail, I wanted to be as unobtrusive as possible when I visited the homes of my subjects. It was important to me that I did not knowingly frighten or control the animals I was photographing. I neither scripted their movements nor body positions, carried large lights nor intrusive equipment, nor manipulated them overtly.

For this series of photographs, I used a Spectra Polaroid camera with a macro or close-up lens. The camera is small, with a soft on-camera flash, and can be operated with one hand, and the Polaroid medium allowed me to view in the moment what I was photographing. To isolate transitory instances of contact between people and their companion animals, I often took pictures without looking through the lens of the camera. This strategy allowed for coincidence and spontaneity to play a large role in the images. Rarely does the face of the human or animal show in the picture, and, because of the nature of the close-up lens, body parts are fragmented and mixed together. The space within the photographs is often ambiguous, as is the particular action taking place in the image (figure 2.9). These momentary glimpses of contact between pet and human allow the viewer to imagine the entirety of the scene and form her own open-ended sense of meaning about the animal and human subjects in the images. The small, grainy photographs, muted color palette, fragmentary nature of the figures, and spatial ambiguity all develop a unique visual vocabulary for the depictions of animals. This way of seeing animals offers an alternative to the overly processed images of commercial photographers, which often reflect less of the nature of the animals being photographed and more of the desires of the humans for conventional representations.

FIGURE 2.8. Julia Schlosser, “Untitled (Alice with Sam),” from the series Contact, 2005. Archival pigment print scanned from Polaroid, 6¾” × 5½“. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Pet owners come to know the minds of the animals they live with, and the animals come to know their owners’ minds, in myriad ways: by paying attention to the everyday behavior patterns of each other, by watching and listening to each other’s reactions when confronted with new situations (for example, those created by other people and animals), and by engaging in touch. My emphasis has been on knowledge gained through touch, touch through play, mutual social grooming, tending, and care (figure 2.10). The sensory functions of touch and sight are profoundly interconnected, facilitating the formation of social connections or bonds between humans and domesticated animals. I believe that the intertwined nature of touch and sight, and the strong social connection that humans share with companion animals, allow photographs of humans and animals touching to create a special nexus of embodied perception for the viewer.

FIGURE 2.9. Julia Schlosser, “Untitled (Pepy with Hazel),” from the series Contact, 2005. Archival pigment print scanned from Polaroid, 6¾” × 5½“. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Using photography, these four artists have explored the possibilities of understanding animals through the vehicle of the body. Each captures a point of contact between animal and human subjects, an intersection between animal and human bodies. The act of contact, this moment of embodied knowledge, is then transferred to the viewer through the viewer’s own felt-senses. Absent communication with language, touch is one avenue by which humans and animals learn about each other (and their worlds) and form relationships. Aware that domesticated pet animals often welcome human contact, these artists are free to explore the rich and complex data communicated from established and incidental patterns of contact with animals. This knowledge, intuitive and subtly nuanced, is transmitted directly to viewers through their felt-senses. For companion animals, touch is one of the primary methods with which they can communicate with humans, and more focused observation of the ways they express themselves through touch provides for wide-ranging and perhaps validating evidence of their minds.

FIGURE 2.10. Julia Schlosser, “Untitled (Sebastian with Julia),” from the series Contact, 2005. Archival pigment print scanned from Polaroid, 6¾” × 5½”. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Notes

This chapter is dedicated to Claire, who touched my life. I am very grateful to Bob and Julie for their discerning editorial skills and gently relentless encouragement. Thanks also to the artists for their generosity in allowing reproduction of their artwork in this publication.

References

Baker, S. 2000. The Postmodern Animal. London: Reaktion.

——. 2001. Picturing the Beast: Animals, Identity, and Representation. Champaign: University of Illinois Press.

Candlin, F. 2006. “The Dubious Inheritance of Touch: Art History and Museum Access.” Journal of Visual Culture 5, no. 2: 137–154.

Casanave, M. 2002. Beware of Dog. Carmel, CA: Center for Photographic Art.

Dover, B. 2007a. Eye to Eye. Dubbo, AUS: Western Plains Cultural Centre.

——. 2007b. Interrogating Gaze. Townsville, AUS: Pinnacles Gallery.

Kuzniar, A. A. 2006. Melancholia’s Dog: Reflections on Our Animal Kinship. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Levinson, B. M. 1972. Pets and Human Development. Springfield, IL: Thomas.

Merleau-Ponty, M. 1962 [1945]. The Phenomenology of Perception. Trans. C. Smith. New York: Humanities.

Olmert, M. D. 2009. Made for Each Other: The Biology of the Human-Animal Bond. Cambridge: Da Capo.

Perricone, C. 2007. “The Place of Touch in the Arts.” Journal of Aesthetic Education 41, no. 1: 90–104.

Pratt, J. W., and A. Mason. 1981. The Caring Touch. London: HM+M.

Schlosser, J. 2007. “The Postmodern Pet: Images of Companion Animals in Contemporary Photography and Video.” Masters thesis. California State University, Northridge.

Schneemann, C. 1997. More Than Meat Joy: Performance Works and Selected Writings. Ed. B. R. McPherson. Kingston, NY: McPherson.

——. 2002. Imaging Her Erotics: Essays, Interviews, Projects. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Serpell, J. 1986. In the Company of Animals. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ullrich, P. 1996–1997. “Touch This: Tactility in Recent Contemporary Art.” New Art Examiner 24 (December/January): 10–15.

Weber, R. 1990. “A Philosophical Perspective on Touch.” In K. E. Barnard and T. B. Brazelton, eds., Touch: The Foundation of Experience, pp. 11–43. Madison, CT: International Universities Press.

Weintraub, L. 1998. “Interspecies Eros.” In M. Seppälä, J. P. Vanhala, and L. Weintraub, eds., Animal. Anima. Animus, pp. 128–137. Pori: Pori Art Museum.

Wyschograd, E. 1981. “Empathy and Sympathy as Tactile Encounter.” Journal of Philosophy 6:25–42.