There is little doubt that animals are conscious. Animals hunt prey, escape predators, explore new environments, eat, mate, learn, feel, and so forth. If one defines consciousness as being aware of external events and experiencing mental states such as sensations and emotions (Natsoulas 1978), then gorillas, dogs, bears, horses, pigs, pheasants, cats, rabbits, snakes, magpies, wolves, elephants, and lions, to name a few creatures, clearly qualify. The contentious issue is, do these animals know that they are perceiving an external environment and experiencing internal events? Are animals self-conscious?

Recent attempts at understanding animal consciousness (e.g., Edelman and Seth 2009) agree that nonhuman animals most probably possess “primary” (or “minimal”) consciousness. But these views also argue that, unlike humans, animals lack many (but not all) elements that make up higher-order consciousness—the capacity to reflect on the contents of primary consciousness. In this chapter I will aim at offering a more elaborate picture of this position. I will present detailed information on what is meant by “higher-order consciousness”—i.e., self-awareness. I will suggest that some dimensions of self-awareness (e.g., self-recognition, metacognition, mental time travel) may be observed in several animals, but that numerous additional aspects (e.g., self-rumination, emotion awareness) seem to be absent. Some other self-related processes, such as Theory-of-Mind, have been identified in animals, but not as the full-fledged versions found in humans. I will postulate that these differences in levels of self-awareness between humans and animals may be attributable to one distinctive feature of human experience: the ability to engage in inner speech.

Definitions, Measures, and Effects of Self-Awareness

Mead (1934) established a classic distinction between focusing attention outward toward the environment (consciousness), and inward toward the self (self-awareness). This framework was recaptured and expanded by Duval and Wicklund (1972). It became very popular in experimental social and personality psychology, where it has been guiding empirical research for more than four decades (see Carver 2003 for a review).

Unconsciousness refers to the absence of processing of information, either from the environment or the self. As previously stated, consciousness constitutes the processing of environmental information or responding to external stimuli. Cabanac, Cabanac, and Parent (2009) suggest that this kind of consciousness (the nonreflective type) could very well be present in reptiles, including tortoises, turtles, lizards, snakes and crocodiles, and in birds and mammals. These animals possess comparable brain volume (as measured by the ratio of brain to body mass), structure, and neurochemistry and, like conscious humans, exhibit emotions, feel pleasure, play, and dream.

Self-awareness is usually defined as becoming the object of one’s own attention. It represents a state in which one actively identifies, processes, and stores information about the self (Morin 2004). Self-awareness constitutes a complex multidimensional phenomenon that comprises various self-domains (e.g., thinking about one’s past and future, emotions, thoughts, personality traits, preferences, intentions; sense of agency) and corollaries (e.g., making inferences about others’ mental states, self-description, self-evaluation, self-esteem, self-regulation, self-efficacy, death awareness, self-conscious emotions, self-recognition, self-talk). Self-awareness also entails knowing that one shows some continuity as a person or entity across time and that one distinguishes oneself from the rest of the environment (Kircher and David 2003).

Initial empirical work focused on short-term effects and long-term consequences of being self-aware. Much of this research involved exposing participants to self-focusing stimuli known to remind the person of his or her object status to others—e.g., mirrors, cameras, an audience, recordings of one’s voice; such stimuli reliably produce heightened self-awareness (Carver and Scheier 1978). Other manipulations and measures of self-awareness include 1. questionnaires that assess dispositional self-focus (Fenigstein, Scheier, and Buss 1975) or spontaneously occurring fluctuations in self-awareness (Govern and Marsch 2001); 2. first-person singular pronoun use (Davis and Brock 1975); 3. self-novelty manipulation (Silvia and Eichstaedt 2004), where participants are invited to write about ways in which they differ from others; 4. word-recognition measures (Eichstaedt and Silvia 2003), where subjects are asked to identify self-relevant or self-irrelevant words as quickly as possible; and 5. match between self- and other-ratings on cognitive or personality measures to evaluate self-knowledge in healthy people (Hoerold et al. 2008) and self-awareness of deficits in patients with traumatic brain injury (Cocchini et al. 2009). Note that all these measurement techniques are inappropriate for animals because they require language; to my knowledge the most used nonverbal measure of self-awareness is self-recognition, which will be discussed in another section.

Inducing self-awareness with self-focusing stimuli produces self-evaluation (Duval and Wicklund 1972), whereby the person compares any given salient self-aspect to an ideal representation of it. Self-criticism is then likely to occur, leading to an avoidance of the state of self-awareness or a reduction of the intraself discrepancy by either modifying the target self-aspect or by changing the ideal itself. Another effect of self-awareness is emotional intensity—the proposal that focusing on one’s emotions or physiological responses amplifies one’s subjective experience (Gibbons 1983). To illustrate, empirical evidence suggests that angry self-aware individuals behave more aggressively than nonself-aware participants. Self-awareness also increases accurate access to one’s self-concept; for instance, self-reports of self-aware individuals are more accurate. Other effects or consequences of self-awareness are heightened consistency between one’s behavior and attitudes, increased self-disclosure in intimate relationships, stronger reaction to social rejection, greater social conformity, and lower antinormative behavior (see Franzoi 1986 for references). While it is ultimately pointless to ponder if animals exposed to self-focusing stimuli would, like humans, engage in self-evaluation, “self-disclose” more, or act more ethically, it is surely intriguing to wonder if they would become more aggressive if angered or if they would react more strongly to social rejection—these are potentially observable events. Remarkably, this has never been done—i.e., trying to replicate some effects and consequences of self-awareness in animals using self-focusing stimuli. Positive results would suggest the presence of the aforementioned forms of self-awareness in tested creatures. Of course this assumes that the presence of a camera or a mirror would successfully induce self-focus in animals.

Past research also shows that self-awareness increases the likelihood of more effective self-regulation (e.g., Carver and Scheier 1981). Self-regulation includes altering one’s behavior, resisting temptation, changing one’s mood, selecting a response from various options, and filtering irrelevant information (Baumeister and Vohs 2003). Do animals self-regulate? They must be able to monitor their ongoing behavior and compare it to set goals or else they would not survive. But, given the demonstrated importance of speech-for-self in self-regulation, I would suggest that animal self-regulation is much more primal than that of humans. Vygotsky (1962 [1934]) pioneered the view that language can be used as a verbal self-guidance device, and decades of work on private speech use in problem solving, planning, and decision making support this view (Winsler 2009). In short, and depending on the content of speech-for-self, people who rely on self-talk while engaged in self-regulatory activities (as previously defined) perform significantly better than those who do not. Thus nonverbal animal and verbal human self-regulation should probably not be equated.

Although self-awareness clearly represents an evolutionary advantage, it has its setbacks as well (Leary 2004). In humans excessive self-focus creates worry, guilt, shame, jealousy, insomnia, etc., and may contribute to social anxiety (Buss 1980), depression (Pyszczynsky and Greenberg 1987), and even suicide (Baumeister 1991); unhealthy people are also known to self-ruminate (Smith and Alloy 2009). Do animals experience these psychological ailments? To my knowledge wild animals have never been observed worrying and do not seem to experience sleeping difficulties as a result. Note that some lab animals (e.g., white rats) show evidence of anxiety when asked to perform extremely difficult discriminatory tasks (Cook 1939). Maybe they can feel guilty or jealous—it’s hard to say. There is no evidence of suicide in animals (Ramsden and Wilson 2010), suggesting that nonhuman creatures may not be able to mentally represent their own death. Do animals possess a more general awareness of death? Here the evidence is mixed. On one hand, we have African elephants known to pick up and scatter the bones of deceased elephants (McComb, Baker, and Moss 2006). Perhaps these elephants are aware of death, but the bone scattering could also be seen as simple survival behavior that hides their migration routes or feeding patterns. On the other hand, the way rabbits react to the death of their companion is puzzling. While some cautiously smell the body of the deceased, others take turns lying nested against the dead rabbit, and all eventually abandon the body permanently. J. A. Smith (2005) suggests that these behaviors indicate an understanding that a partner has undergone a permanent and catastrophic change.

Animals apparently do not blush (Darwin 1872)—a physiological response typically associated with social anxiety. Rats have been shown to experience negative emotional states, or “depression,” as suggested by increased sensitivity to the unanticipated loss of food reward (Burman et al. 2008). Humans are more sensitive to reward loss than gain, but depressed individuals tend to be even more responsive to reward loss. Although pet owners may describe their cat or dog as being “depressed,” clear scientific data to this effect is still lacking. In addition, such depressive episodes, if they do exist, may have little to do with heightened self-awareness or with the animal being aware of experiencing them.

In humans, self-awareness does not represent a uniform construct and is made up of two different tendencies (Trapnell and Campbell 1999): self-reflection, which constitutes an authentic curiosity about the self, and self-rumination, which represents anxious attention paid to the self. While it is clearly impossible to know if self-aware animals are genuinely curious about their selves, one can state with some confidence that self-rumination in animals is unlikely. Self-rumination consists in recurrent, intrusive, and disruptive thoughts. These thoughts are most probably articulated with inner speech, and, indeed, measures of self-rumination strongly correlate with the Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire (Conway et al. 2000)—in essence an inner speech scale. Animals lack inner speech, but perhaps they could “ruminate” with mental images? Self-ruminators are more likely to suffer from depression, anxiety, stress, and social phobia or withdrawal; they also experience problem-solving and concentration difficulties (Smith and Alloy 2009). Animals do not seem to present any of these problems, at least not as self-induced conditions.

Agency and Mental Time Travel

As indicated previously, self-awareness consists of various dimensions, among which are sense of agency and mental time travel. Most animals probably have a sense of agency based on representations of the relation between their action and the subsequent effects that develop through operant conditioning. This capacity allows organisms to interact with and control their own environment (Engbert, Wohlschläger, and Haggard 2008).

Mental time travel (MTT), also known as autonoetic consciousness, represents the ability to remember personally experienced events that occurred in the past and to imagine personal happenings in the subjectively felt future (Tulving and Kim 2009). It includes a “what, where, and when” (www) of events, as well as the conscious reexperiencing of oneself in the remembered event. The “remembering one’s past” portion of MTT has been assessed in various animals; in primates a typical experiment goes as follows. The animal first witnesses a unique event—e.g., seeing a familiar person doing something odd, such as stealing a cell phone. This is followed by a fifteen-minute retention interval, and then the subject is shown three photographs (two distractors and the witnessed event) and is asked to select the correct photograph depicting what he/she had seen before. A good answer is rewarded with food. Chimpanzees and gorillas perform significantly higher than chance on that type of trial (Menzel 2005). Variations of this task have been created to test MTT in other creatures such as scrub jays, magpies, and rats. They also remember the “www” of personal events, suggesting rudiments of an MTT system (Roberts and Feeney 2009). It remains impossible to determine if these animals actually mentally relive the events.

Can animals anticipate and plan for the future? The evidence is very limited and is open to alternate interpretations. Scrub jays can anticipate the need for specific food at breakfast the following day by storing seeds in novel locations where they have not encountered food before, and captive chimpanzees will cache stones they will later hurl at human visitors (Roberts and Feeney 2009). However, the possibility remains that in both cases these animals rely on semantic knowledge (generalized knowledge that does not involve anticipation of a specific event—e.g., human visitors periodically appear) rather than on genuine planning (human visitors will appear tomorrow morning). In short, it is still unclear if animals are “stuck in time” or not.

Private and Public Self-Awareness

One fundamental distinction that has been proposed early on is the difference between private and public self-focus (Fenigstein, Scheier, and Buss 1975). Self-awareness includes a knowledge of one’s own mental states (private self-aspects) such as thoughts, emotions, preferences, personality traits, opinions, goals, sensations, attitudes, etc., and visible characteristics (public self-aspects) such as one’s body, physical appearance, mannerisms, and behaviors.

Humans routinely focus on private and public self-dimensions. Do animals also focus on both private and public self-aspects? All animals must possess some rudimentary form of body self-awareness (Bekoff and Sherman 2004). They position their body parts in space so that they do not collide with nearby conspecifics and they travel as a coordinated hunting unit or flock. Also, some animals are capable of self-recognition, which requires a mental representation of one’s body (Mitchell 2002). Note that one’s body can be apprehended both as a private self-aspect (kinesthetic experience) and public self-aspect (the image of one’s body seen in a mirror). Do animals reflect on their physical appearance? Unlike humans, they do not wear body adornments such as bracelets and beads to be more attractive (Mitchell 2002). This suggests a different form of self-presentation in humans than in other animals.

Do animals reflect on their unobservable mental states? It is virtually impossible to determine animals’ awareness of their own sensations, motives, opinions, or attitudes. Animals, including primates, dogs, cats, and birds, certainly experience emotions. Physiological, behavioral, and cognitive changes that spontaneously accompany affective states are remarkably similar in humans and animals (Paul, Harding, and Mendl 2005). Chimpanzees and orangutans display emotional reactions of pride, shame, and embarrassment (Tracy and Robins 2004). However, an organism may experience emotions, including self-conscious emotions, without being aware of them (Salzen 1998), and, to my knowledge, evidence for emotional awareness in animals is nonexistent. This remark also applies to animals’ awareness of preferences (e.g., food). Animals do have preferences, but there is no known way of determining if they know about their preferences. Animals also exhibit individual differences, but awareness of one’s personality characteristics in terms of traits entails linguistic representation that nonhuman creatures lack.

Metacognition

What about awareness of thoughts? Metacognition consists in thinking about thinking or cognition about cognition (Nelson and Narens 1994). Examples of metacognition in humans are becoming aware of a thought one just had or a solution to a problem one just discovered. One other case of metacognition is when we feel uncertain about some information we might possess or not—for instance: can I recall this phone number or do I need to look it up in the directory? Uncertainty responses during perceptual tasks (e.g., tone discrimination) or memory tasks (e.g., item recall) are often used in animals as an indicator of metacognition (Smith 2009). In addition to discrimination responses per se, subjects are given the possibility to decline completion of any trials they want. Doing so suggests uncertainty and probably knowledge that information is missing to adequately perform the task. Available evidence indicates that dolphins and monkeys, but not rats, make uncertainty responses in a variety of tasks (J. D. Smith 2005). Hampton (2001) reports studies on “memory awareness” showing that rhesus monkeys, but not pigeons, turn down trials when they are uncertain they will pass a memory test.

Another metacognition test consists in asking subjects to make metaconfidence judgments in which they evaluate up to what point they are confident that a previously made response is correct (Son and Kornell 2005). This requires metacognition because one has to think about one’s own knowledge (or lack thereof) when assessing one’s confidence in an answer. In a representative experiment, monkeys are asked to identify the longest of nine lines. The “metaconfidence judgment” part of the task consists in subjects making a high bet (for high reinforcement) or a low bet (for lower reinforcement) on the correctness of their previous answer. Making a high bet means that the animal is very confident in the previously given answer, and vice versa. Monkeys are indeed able to make accurate confidence judgments.

Not only do some animals decline a task because of lack of knowledge—some will also seek information when it is incomplete (Call 2005), suggesting that they are aware of not knowing. Subjects in a typical study have to choose one of two containers to obtain a reward. The experimenter places food in one of the two containers. In one situation subjects can see in which container the food is put before choosing. In another situation they do not have direct visual access to that information, but if they bend down and look under the containers they can see where the food is. Chimpanzees, gorillas, and orangutans actively seek additional information in that type of experiment by looking under the containers before choosing; dogs, however, do not.

Various experimental paradigms consequently suggest that some animals could be aware of their thoughts, although alternative nonmentalistic (first-order, as opposed to second-order) explanations are available (Carruthers 2008). Also, animals show functional parallels to human conscious metacognition, but they may not experience everything that can accompany conscious metacognitive experience in humans.

Self-Recognition and Theory-of-Mind

Most organisms that are confronted with a reflective surface react as if they were seeing another conspecific creature by engaging in a variety of social responses such as bobbing, vocalizing, and threatening. Only humans, chimpanzees, orangutans, and bonobos, elephants, dolphins, and magpies have been shown to exhibit spontaneous mirror-guided self-exploration, e.g., self-directed behaviors such as examining body parts only visible in the mirror (see Morin 2011 for a review). The aforementioned animals also pass the more formal “mark test” and will touch a red dot that has been inconspicuously applied to their brow or forehead (or throat feathers in magpies’ case). Emitting self-directed responses in front of a mirror and passing the mark test indicate self-recognition. In humans this developmental landmark is achieved between eighteen and twenty-four months of age (Amsterdam 1972).

How does self-recognition relate to self-awareness? According to Gallup (1982), emitting self-directed behaviors in front of a mirror indicates that the organism can take itself as the object of its own attention. In addition, re-cognizing oneself in front of a mirror presupposes preexisting “self-cognition” (i.e., self-knowledge, a self-concept) and therefore self-awareness. There is little doubt that self-recognition implies some form of self-awareness; rather, the question should be: What type, or what level, of self-awareness is involved? Mitchell (2002) and others suggest that self-recognition only requires knowledge of one’s body. The organism matches the kinesthetic representation of the body with the image seen in the mirror and infers that “it’s me.” This interpretation implies that an awareness of one’s own thoughts (or any other more private dimensions of the self) is not needed for self-recognition to take place. An awareness of private self-aspects does not seem relevant for self-recognition, whereas an awareness of the body is critical for self-identification in front of a mirror. Note that perhaps self-recognizing creatures do have access to their thoughts (e.g., metacognition), but passing the self-recognition test does not demonstrate this.

Theory-of-Mind (ToM) consists in attributing mental states such as goals, intentions, beliefs, desires, thoughts, and feelings to other social agents (Gallagher and Frith 2003). The social cognitive and evolutionary benefits of ToM are the ability to predict others’ behavior and to help, avoid, or deceive others as the situation dictates. Do animals engage in ToM? This represents a highly controversial question, with some claiming that primates, and possibly birds, (e.g., ravens) do (Gallup 1982; Premack and Woodruff 1978), and others denying ToM in animals altogether (e.g., Heyes 1998). A more likely scenario is that primates are capable of some forms of ToM but do not possess the fully developed human version. While early experiments on chimpanzees seemed to imply an ability to understand human goals, much subsequent work increasingly suggested that they do not appreciate human goals or visual perception, as exemplified by Povinelli and Eddy’s study (1996) in which chimpanzees begged from humans facing them, but also solicited the attention of other humans who had buckets over their heads. According to Call and Tomasello (2008), more recent evidence instead shows an understanding of goals, intentions, perceptions, and knowledge in others—but not of others’ beliefs. In a typical experiment on intention understanding, the animal observes the human experimenter trying to turn on a light with his head because his hands are occupied holding a blanket. The subject reacts to this not by imitating the experimenter’s behavior (miming turning on a light with its head) but rather by imitating the intention behind the physical constraint—by turning on the light with its hands.

Povinelli and Vonk (2003) remain skeptical and propose that chimpanzees form mental concepts of visible, concrete objects in their environments (e.g., apples, facial expressions, leopards), but not about inherently unobservable things (e.g., God, gravity, love). In ToM experiments, chimpanzees would reason solely about the abstracted statistical regularities that exist among certain events and the behavior, postures, and head movements of others (behavioral abstractions), but not about others’ unobservable mental states.

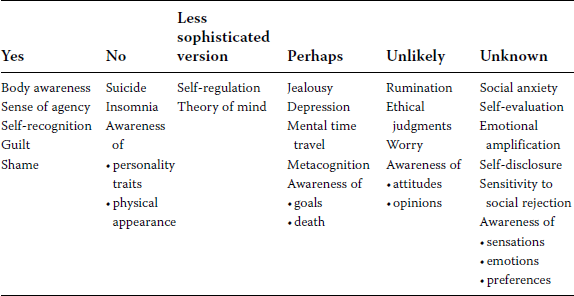

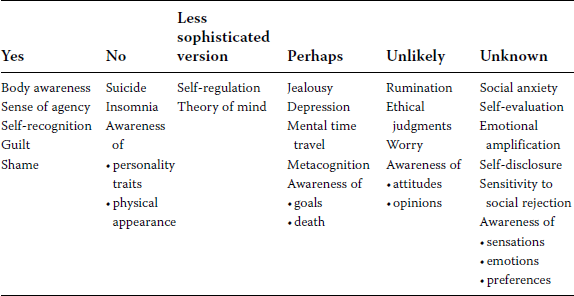

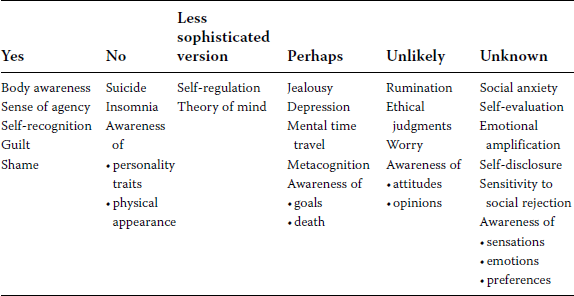

In this chapter I raised the question What are animals conscious of? Table 16.1 summarizes my analysis. I suggest that some animals are conscious of their body (as measured by self-recognition) and of being the agent behind their actions (sense of agency). Animals seem to be unaware of various private and public self aspects (e.g., traits, physical appearance, attitudes), and some might know about their thoughts (metacognition) as well as their past and future (MTT). Unlike humans, who can experience negative states resulting from excessive self-focus, animals do not appear to worry, ruminate, or self-destruct. However, like humans, animals seem to engage in self-regulation and ToM, but these represent less refined versions. Take note that the last “unknown” column contains quite a few self-related processes, indicating that our knowledge of animal self-awareness is still precarious. This analysis supports the widespread view that self-awareness differences in humans and animals are not radical and come in degrees.

TABLE 16.1. What Self-Aspects and Processes Are Animals Aware Of?

Why is self-awareness less sophisticated in animals? The lack of language in animals is often cited, but I propose more specifically that it is the absence of inner speech in animals that should be credited. Inner speech is known to contribute to the development of self-awareness in humans (e.g., DeSouza, DaSilveira, and Gomes 2008). Self-directed speech allows us to verbally label our internal experiences and characteristics; as a result, these become more salient—more conscious. A significant positive correlation exists between diverse validated scales measuring the frequency of private self-focus and use of inner speech (see Morin 2005 for a review); accidental loss of inner speech following brain injury impedes self-awareness (Morin 2009). In light of this evidence, I would predict that linguistically tutored apes, such as those trained by Savage-Rumbaugh, Fields, and Taglialatela (2000), should exhibit heightened self-awareness, assuming that speech-for-self automatically follows social speech.

I would like to thank Breanne Hamper, Petra Kamstra, and Jack Robertson for their helpful editorial comments on previous versions of this chapter.

References

Amsterdam, B. 1972. “Mirror Self-Image Reactions Before Age Two.” Developmental Psychobiology 5:297–305.

Baumeister, R. F. 1991. Escaping the Self. New York: Basic Books.

Baumeister, R. F., and K. D. Vohs. 2003. “Self-Regulation and the Executive Function of the Self.” In M. R. Leary and J. P. Tangney, eds., Handbook of Self and Identity, pp. 197–217. New York: Guilford.

Bekoff, M., and P. W. Sherman. 2004. “Reflections on Animal Selves.” Trends in Ecology and Evolution 19:176–180.

Burman, O. P., R. M. A. Parker, E. S. Paul, and M. Mendl. 2008. “Sensitivity to Reward Loss as an Indicator of Animal Emotion and Welfare.” Biology Letters 4:330–333.

Buss, A. H. 1980. Self-Consciousness and Social Anxiety. San Franscisco: Freeman.

Cabanac, M., A. J. Cabanac, and A. Parent. 2009. “The Emergence of Consciousness in Phylogeny.” Behavioural Brain Research 198:267–272.

Call, J. 2005. “The Self and Others: A Missing Link in Comparative Social Cognition.” In H. S. Terrace and J. Metcalfe, eds., The Missing Link in Cognition: Origins of Self-Knowing Consciousness, pp. 321–342. New York: Oxford University Press.

Call, J., and M. Tomasello. 2008. “Does the Chimpanzee Have a Theory of Mind? Thirty Years Later.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 12:187–192.

Carruthers, P. 2008. “Meta-cognition in Animals: A Skeptical Look.” Mind and Language 23:58–89.

Carver, C. S. 2003. “Self-Awareness.” In M. R. Leary and J. P. Tangney, eds., Handbook of Self and Identity, pp. 179–196. New York: Guilford.

Carver, C. S., and M. F. Scheier. 1978. “Self-Focusing Effects of Dispositional Self-Consciousness, Mirror Presence, and Audience Presence.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 36:324–332.

——. 1981. Attention and Self-Regulation: A Control Theory Approach to Human Behavior. New York: Springer.

Cocchini, G., A. Cameron, N. Beschin, and A. Fotopoulou. 2009. “Anosognosia for Motor Impairment Following Left Brain Damage.” Neuropsychologia 23, no. 2: 223–230.

Conway, M., P. A. R. Csank, S. L. Holm, and C. K. Blake. 2000. “On Assessing Individual Differences in Rumination on Sadness.” Journal of Personality Assessment 75:404–425.

Cook, S. W. 1939. “The Production of ‘Experimental Neurosis’ in the White Rat.” Psychosomatic Medicine 1:293–308.

Darwin, C. 1872. The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. London: John Murray.

Davis, D., and T. C. Brock. 1975. “Use of First Person Pronouns as a Function of Increased Objective Self-Awareness and Prior Feedback.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 11:381–388.

DeSouza, M. L., A. DaSilveira, and W. B. Gomes. 2008. “Verbalized Inner Speech and the Expressiveness of Self-Consciousness.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 5, no. 2: 154–170.

Duval, S., and R. A. Wicklund. 1972. A Theory of Objective Self-Awareness. New York: Academic.

Edelman, D. B., and A. K. Seth. 2009. “Animal Consciousness: A Synthetic Approach.” Trends in Neurosciences 32, no. 9: 476–484.

Eichstaedt, J., and P. J. Silvia. 2003. “Noticing the Self: Implicit Assessment of Self-Focused Attention Using Word Recognition Latencies.” Social Cognition 21: 349–361.

Engbert, K., A. Wohlschläger, and P. Haggard. 2008. “Who Is Causing What? The Sense of Agency Is Relational and Efferent-Triggered.” Cognition 107, no. 2: 693–704.

Fenigstein, A., M. F. Scheier, and A. H. Buss. 1975. “Public and Private Self-Consciousness: Assessment and Theory.” Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 36:1241–1250.

Franzoi, S. L. 1986. “Self-Consciousness and Self-Awareness: An Annotated Bibliography of Theory and Research.” Social and Behavioral Sciences Documents 16, no. 1: listing 2744, 1–53.

Gallagher, H. L., and C. D. Frith. 2003. “Functional Imaging of ‘Theory of Mind’.” Trends in Cognitive Science 7, no. 2: 77–83.

Gallup, G. G., Jr. 1982. “Self-Awareness and the Emergence of Mind in Primates.” American Journal of Primatology 2:237–248.

Gibbons, F. X. 1983. “Self-Attention and Self-Report: The ‘Veridicality’ Hypothesis.” Journal of Personality 51:517–542.

Govern, J. M., and L. A. Marsch. 2001. “Development and Validation of the Situational Self-Awareness Scale.” Consciousness and Cognition 10, no. 3: 366–378.

Hampton, R. R. 2001. “Rhesus Monkeys Know When They Remember.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 98:5359–5362.

Heyes, C. M. 1998. “Theory of Mind in Nonhuman Primates.” Behavioral and Brain Sciences 21, no. 1: 101–134.

Hoerold, D., P. M. Dockree, F. M. O’Keeffe, H. Bates, M. Pertl, and I. H. Robertson. 2008. “Neuropsychology of Self-Awareness in Young Adults.” Experimental Brain Research 186, no. 3: 509–515.

Kircher, T., and A. S. David. 2003. “Self-Consciousness: An Integrative Approach from Philosophy, Psychopathology, and the Neurosciences.” In T. Kircher and A. S. David, eds., The Self in Neuroscience and Psychiatry, pp. 445-473. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Leary, M. R. 2004. The Curse of the Self: Self-Awareness, Egotism, and the Quality of Human Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

McComb, K., L. Baker, and C. Moss. 2006. “African Elephants Show High Levels of Interest in the Skulls and Ivory of Their Own Species.” Biology Letters 2:26–28.

Mead, G. H. 1934. Mind, Self, and Society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Menzel, C. 2005. “Progress in the Study of Chimpanzee Recall and Episodic Memory.” In H. S. Terrace and J. Metcalfe, eds., The Missing Link in Cognition: Origins of Self-Knowing Consciousness, pp. 188–224. New York: Oxford University Press.

Mitchell, R. W. 2002. “Subjectivity and Self-Recognition in Animals.” In M. R. Leary and J. P. Tangney, eds., Handbook of Self and Identity, pp. 3–15. New York: Guilford.

Morin, A. 2004. “A Neurocognitive and Socioecological Model of Self-Awareness.” Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs 130, no. 3: 197–222.

——. 2005. “Possible Links Between Self-Awareness and Inner Speech: Theoretical Background, Underlying Mechanisms, and Empirical Evidence.” Journal of Consciousness Studies 12, no. 4–5: 115–134.

——. 2009. “Self-Awareness Deficits Following Loss of Inner Speech: Dr. Jill Bolte Taylor’s Case Study.” Consciousness and Cognition 18, no. 2: 524–529.

——. 2011. “Self-Recognition, Theory-of-Mind, and Self-Awareness: On What Side Are You On?” Laterality 16, no. 3: 367–383.

Natsoulas, T. 1978. “Consciousness.” American Psychologist 33, no. 10: 906–914.

Nelson, T. O., and L. Narens. 1994. “Why Investigate Metacognition?” In J. Metcalfe and A. P. Shimamura, eds., Metacognition: Knowing About Knowing, pp. 1–25. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Paul, E. S., E. J. Harding, and M. Mendl. 2005. “Measuring Emotional Processes in Animals: The Utility of a Cognitive Approach.” Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 29, no. 3: 469–491.

Povinelli, D. J., and T. J. Eddy. 1996. “What Young Chimpanzees Know About Seeing.” Monographs of Social Research in Child Development 61:1–152.

Povinelli, D. J., and J. Vonk. 2003. “Chimpanzee Minds: Suspiciously Human?” Trends in Cognitive Science 7:157–160.

Premack, D., and G. Woodruff. 1978. “Does the Chimpanzee Have a Theory of Mind?” Behavioral and Brain Sciences 1, no. 4: 515–526.

Pyszczynsky, T., and J. Greenberg. 1987. “Self-Regulatory Perseveration and the Depressive Self-Focusing Style: A Self-Awareness Theory of Reactive Depression.” Psychological Bulletin 10:122–138.

Ramsden, E., and D. Wilson. 2010. “The Nature of Suicide: Science and the Self-Destructive Animal.” Endeavour 34, no. 1: 21–24.

Roberts, W. A., and M. C. Feeney. 2009. “The Comparative Study of Mental Time Travel.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 13:271–277.

Salzen, E. A. 1998. “Emotion and Self-Awareness.” Applied Animal Behaviour Science 57:299–313.

Savage-Rumbaugh, S., W. M. Fields, and J. Taglialatela. 2000. “Ape Consciousness—Human Consciousness: A Perspective Informed by Language and Culture.” American Zoologist 40:910–921.

Silvia, P. J., and J. Eichstaedt. 2004. “A Self-Novelty Manipulation of Self-Focused Attention for Internet and Laboratory Experiments.” Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, and Computers 36:325–330.

Smith, J. A. 2005. “‘Viewing’ the Body: Toward a Discourse of Rabbit Death.” World-views 9, no. 2: 184–202.

Smith, J. D. 2005. “Studies of Uncertainty Monitoring and Metacognition in Animals and Humans.” In H. S. Terrace and J. Metcalfe, eds., The Missing Link in Cognition: Origins of Self-Knowing Consciousness, pp. 247–271. New York: Oxford University Press.

——. 2009. “The Study of Animal Metacognition.” Trends in Cognitive Sciences 13, no. 9: 389–396.

Smith, J. M., and L. B. Alloy. 2009. “A Roadmap to Rumination: A Review of the Definition, Assessment, and Conceptualization of This Multifaceted Construct.” Clinical Psychology Review 29:116–128.

Son, L. K., and N. Kornell. 2005. “Metaconfidence Judgments in Rhesus Macaques: Explicit Versus Implicit Mechanisms.” In H. S. Terrace and J. Metcalfe, eds., The Missing Link in Cognition: Origins of Self-Reflective Consciousness, pp. 296–320. New York: Oxford University Press.

Tracy, J. L., and R. W. Robins. 2004. “Show Your Pride: Evidence for a Discrete Emotion Expression.” Psychological Science 15:194–197.

Trapnell, P. D., and J. D. Campbell. 1999. “Private Self-Consciousness and the Five-Factor Model of Personality: Distinguishing Rumination from Reflection.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 76:284–304.

Tulving, E., and A. S. N. Kim. 2009. “Autonoetic Consciousness.” In P. Wilken, T. Bayne, A. Cleeremans, eds., The Oxford Companion to Consciousness, pp. 96–98. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Vygotsky, L.S. 1962 [1934]. Thought and Language. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Winsler, A. 2009. “Still Talking to Ourselves After All These Years: A Review of Current Research on Private Speech.” In A. Winsler, C. Fernyhough, and I. Montero, eds., Private Speech, Executive Functioning, and the Development of Verbal Self-Regulation, pp. 3–41. New York: Cambridge University Press.