The defences of a Russian gorod comprised earthen ramparts, ditches, walls, gates, and towers. Earthen ramparts were the key feature in artificial defensive works in Russia during the period under discussion here. Earlier fortresses either had no or very few towers. Most walls, with the exception of a few districts, were wooden up to the 15th century.

The height of earthen ramparts (osyp’) varied greatly depending on the military importance of the fortified settlement. They rarely exceeded 4m, except for in the larger cities, where they could be much higher. For example, the ramparts were about 8m high in Vladimir and 10m in Old Ryazan. The ramparts of ‘Yaroslav’s city’ in Kiev were the most formidable, reaching 16m in height and 25–30m in width at the base.

Ramparts were often built of earth or clay, or more rarely of sand or stone. Sand (being too loose) was only used in districts where earth or clay was unavailable. A rampart built of sand had to be strengthened with a wooden casing. Masonry bonded with earth or lime was extremely rare; where stone was in plentiful supply, it was easier to build a stone wall. Where hard ground was not present, only the front side of the rampart (the face of the slope) was made of it while the rear side was raised with less compact soil. To hamper the enemy attacking a rampart, its front side was often coated with clay and watered.

The top of a rampart consisted of a horizontal strip of ground on which a certain type of wall was erected. Its minimum width – if it served as a base for a palisade – was 1.3m. If the rampart had a log wall on top, the strip was naturally wider – as much as 8 or 9m, especially when it supported a wall made of two rows of log cells. Access to the top of a rampart was granted by wooden ladders or steps cut into the ground. To ensure the uninterrupted movement of the defenders along the rampart during a siege, the rear side of the rampart was paved with stone, or a horizontal terrace was built there. A stepped profile was sometimes given to the entire rear side of the rampart.

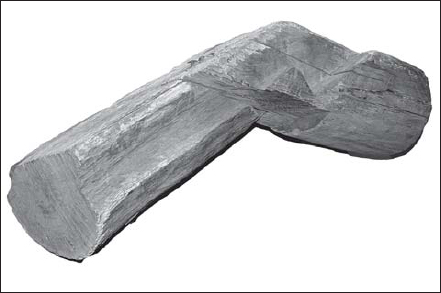

12th-century oak logs discovered in the ramparts of Vladimir. Such logs were used to build an intra-rampart structure, giving it its steepness whilst preventing the earth from sliding down. (Historical Museum in Vladimir)

As a rule, a rampart was asymmetrical in cross-section. The front slope was steeper (usually 40–45 degrees, but no less than 30 degrees) than the back one (25–30 degrees). A considerable steepening of the slope on the front side could be attained by the addition of compacted soil or by facing the rampart with stone or wood. However, in Russian fortresses preference was given to intra-rampart structures. Wooden intra-rampart structures are characteristic not only of Russian but of other Slavic fortresses as well, such as Polish and Czech ones. However, although there are some well-known exceptions, Russian intra-rampart structures differed from those found in Poland or the Czech Republic. In general terms, the typical Polish framework consisted of several layers of logs laid perpendicular to each other, the Czech structure consisted of lattice-work and sometimes featured masonry, while the Russians made use of oak-wood log cells packed with earth.

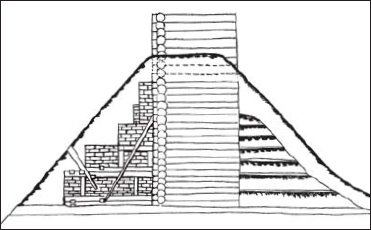

A cutaway view of the rampart of Belgorod. Oak log cells placed close to each other form the base of the rampart. The front wall of the cells was right under the crest of the rampart and found its continuation in a wooden wall on top of it. Facing the cells, in the front part of the rampart there was a wooden framework filled with mud-brick. The rear part of the rampart was strengthened with a layer of clay. The entire intra-rampart structure was covered with earth.

The intra-rampart wooden structure changed with time. The earliest structures of this type were discovered in fortresses built in the late 10th century under Prince Vladimir. The fortifications of Belgorod, Pereyaslavl, and some other cities belong to this type. Structures of this early period are particularly complex. The core of the structure comprised oak-wood log cells placed close to each other so that the front wall of the framework was right under the crest of the rampart. The framework was usually built in such a way that the ends of the logs protruded about 0.5m, and these jutting ends of each shell almost touched those protruding from the next shell. Facing the cells, in the front part of the rampart, a wooden carcass filled with mud-brick bonded with clay was built. Both the carcass and the oak framework were covered with earth. This construction method involved much labour, and was simplified early in the first half of the 11th century when the carcass with mud-brick was dispensed with and only a line of oak cells placed close together was left.

If a rampart was fairly broad, each cell would be long, stretched across the rampart. For extra solidity one or more walls were added, creating several small rooms. For example, the interior of the rampart built in the first half of the 11th century in ‘Yaroslav’s city’ in Kiev reveals oak cells about 19m long (running across the rampart) and 12–16m high. Each cell consists of three long transverse (to the rampart) and seven short longitudinal walls, which, together, divide the cell into 12 rooms. Despite the considerable transverse length of the cells, their facade is located right under the crest of the rampart, as usual.

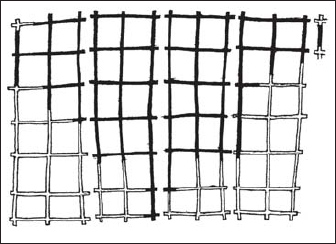

Intra-rampart log cell structures: the structure consisting of separate log cells discovered in the ramparts of ‘Yaroslav’s city’ in Kiev (left), and a solid structure of log cells (right).

Alongside the structure consisting of separate cells, another structure began to be used as early as the first half of the 11th century. The cells of this structure were consolidated by adding overlapping longitudinal logs. This framework also consisted of several rows of cells. Sometimes only the outside cells were filled with earth whereas the inside cells, overlooking the fortress court, were left hollow. The latter were used as storerooms or living quarters.

Wooden log intra-rampart structures of both types – built of separate cells or forming a continuous line – became widespread in the 11th and 12th centuries, particularly in large cities and strategically important fortresses. However, fortresses defending smaller settlements had purely earthen ramparts with no wooden framework inside. In the centuries that followed there was a tendency to simplify the wooden structures, and by the 13th–15th centuries they consisted usually of no more than a primitive oak log wall with short crossbeams directed to the rear.

A ditch was often created in front of a rampart, although it may not always have run along the entire perimeter of the fortifications. For example, in cape layout fortresses the ditch, as a rule, protected the most vulnerable mainland side, cutting the promontory off from the rest of the land; the remaining sides were protected by rivers, deep ravines, and the like.

The earth dug out in the course of making a ditch was used to raise the rampart, so the depth of the ditch generally equalled the height of the adjoining rampart, except when there already was a ravine where the ditch was to be dug, which naturally resulted in the depth of the ditch exceeding the height of the rampart. A ditch usually had a symmetrical profile with walls sloping at 30–45 degrees, with a rounded bottom. Wherever possible, the ditch was filled with water from a river, lake, or other source. When left dry, the bottom of the ditch was filled with sharpened poles. A narrow, horizontal strip of land (or berm) was left between a ditch and a rampart to prevent the rampart sliding into the ditch. These berms were usually about 1m wide.

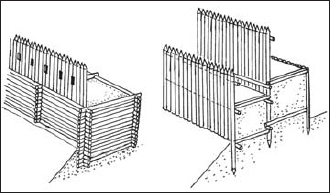

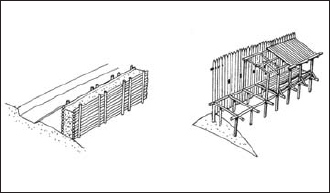

There were three main types of fortress walls: palisades (tyn or chastokol), log walls, and stone walls. The tyn was the simplest type, comprising a row of vertical or slightly inclined, sharpened stakes driven into the ground close to each other. This palisade was usually ‘two spears high’, that is, about 3–4m above ground level. The stakes were driven as deep as 0.5–1m into the ground, and according to archaeological research were 13–18cm thick. About 0.3–0.5m below their pointed ends, the vertical stakes were joined together by a horizontal pole which was either run through special apertures made in the vertical stakes or nailed to them on the outside. On the side of the fortress the palisade was provided with wooden flooring on vertical pillars. This wall-walk for the defenders was called a polati or krovat’. Sometimes a wall-walk consisted of nothing more than a number of short logs driven into the ground, making movement along it much more difficult than on planks.

Methods of using a tyn, and one of the types of fence. A tyn could be set up in two rows, one higher than the other, or combined with a log cell structure. A polati or krovat’ – a wall-walk covered with duckboards – was made behind a tyn. The tyn could have a roof.

A tyn was not necessarily just a row of stakes. It was sometimes supported to the rear by a small earthen embankment or strengthened from behind with angled logs, whose pointed ends jutted out; two rows of tyn might be built (one higher than the other); or a tyn could be combined with a log wall. Some examples of tyn were roofed. Weapons could be fired either over the top of the tyn or through loopholes.

A tyn was the only type of wooden fortification in old Slavic settlements in the 8th–9th centuries; later on it provided protection for small settlements and minor fortresses. However, this simple fortification continued to be extensively used even in large cities and strategically important fortresses. It was erected in less vulnerable sectors of defence where the natural relief of the land hampered attack, for example, along riverbanks in cape layout settlements. Moreover, for a long time the tyn remained the principal type of fortification of the okol’ny gorod/possad. The rather primitive fortifications allocated to these trading areas can be explained by the large areas of land that they occupied. Commercial activities were still closely linked to agriculture, and many citizens were engaged in cattle-breeding and farming. Thus, every homestead had a large plot of land to go with it. Walls of considerable length were difficult to create and hard to defend, and were only meant to protect the inhabitants from wild beasts, gangs of robbers, and nomadic raiders. In times of serious danger the citizens took shelter in the detinets and the okol’ny gorod was set on fire.

Another type of primitive fortification, the fence, was a rare alternative to the tyn. Fences were made of horizontally laid logs squeezed between vertical logs driven into the ground in pairs. The structure of a fence could vary, too; for example, two rows of horizontal logs with earthen filling packed between them could be held in place by vertical ones.

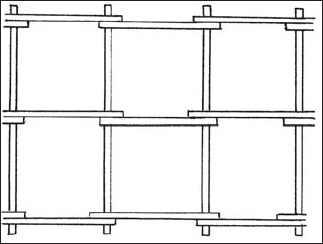

The second half of the 10th century saw the appearance of wooden log walls, created by placing log cells close to each other along the top of a rampart. The cells could have three sides, consisting of a facade stretched along the outer side of the rampart and two transverse walls, or four sides, thus taking on the appearance of a small house. These log cells were called gorodni. They were joined by cross-walls but their facades were not joined together (unlike the later tarassy-style structure).

The thickness of the log wall varied from 2m to 6m while its height was 3m to 5m. The wall usually had two floors and was covered with a roof. The upper floor had loopholes, but there were no merlons on the wall. A wall-walk (boevoy hod) ran behind a parapet supplied with loopholes. The upper part of the wall was built slightly projecting beyond the plane of the wall, so that there was a gap between the upper and lower parts of the wall. The clearance served the same purpose as hoarding or machicolations in European castles: to command the space at the foot of the wall. This overhanging projection is usually called an oblam and the entire projecting upper part of the wall the zaborola. Disputes, however, continue as to the meaning of the two terms: some consider both terms to be synonymous referring only to the projection, while others assume that zaborola stood for the whole of a wall.

Log cell walls were to be found protecting strategically important fortresses, the detinets in a large city, or the most crucial sectors of defence in other fortified settlements (such as the mainland side in a settlement situated on a promontory). Sometimes a log wall and a more primitive palisade could be found in different sectors of the same fortress.

Up until the mid 13th century most fortresses had wooden walls. In the Novgorod lands, stone fortresses first appeared as early as the 11th and 12th centuries, although these were exceptions. Stone castles could also be found in this period in Bogolyubovo (built about 1165 in the Suzdal lands) and in Kholm (1237–38, in west Volhynia). Some urban estates and large monasteries also had stone or brick walls – a choice, however, dictated by artistic and ideological considerations above all, as opposed to military necessity. Wooden walls were considered to be perfectly adequate for military purposes, and were built in most fortresses.

Wooden log walls built in the gorodni style

This type of structure was the most popular in Rus’ between the second half of the 10th and the mid 15th centuries. The upper part of the wall projected slightly forwards as a rule, overhanging the lower part. The resulting clearance, called oblam, was designed with the same aim as hoarding or machicolations in European castles – to command the foot of the wall. The wall was usually built on top of an earthen rampart. In order to add steepness to the rampart and prevent the earth from slipping down, intra-rampart structures were often resorted to. These were wooden log cells placed inside the ramparts and usually filled with earth. Occasionally, however, rows of cells on the inner side of the rampart were left empty and used for living in, for household items, and as storerooms.

Stone defensive walls began to be widely built in the mid 13th century, but even then this was not done all over the country. In some fortresses wooden walls co-existed alongside stone ones. For instance, in the fortress of Velie built in the late 14th–early 15th centuries, one of the walls was stone, 4.4m thick, and the others were made of wood and stood on ramparts. In such timber-and-stone fortresses stone walls were reserved for defending the most vulnerable (usually the mainland) side.

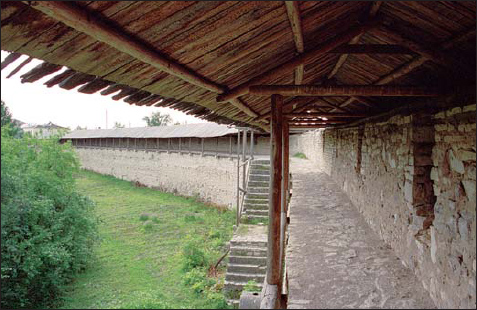

In the 13th–15th centuries the thickness of stone walls varied in different parts of the fortress, reaching 3–4m on the most vulnerable, mainland side while being only 1.5–2m in other places. The walls became thinner towards the top, were crowned with a stone parapet with rectangular merlons, and were usually covered with a gabled wooden roof. The parapet was not less than 55cm thick. The boevoy hod (wall-walk) running behind was to be at least 1.5–2m wide to allow two armed warriors to pass each other. Adding the thickness of the parapet to the width of the wall-walk, one can deduce that the minimum width of the top of the wall would have been 2m.

The second half of the 14th century saw a tendency towards increasing the height of stone walls, and from the early 15th century, with the spread of cannon, walls tended to grow in thickness. They were usually 7.5–9m high, although some were higher. External masonry, called prikladka, was added to pre-existing stone walls to thicken them. Machicolations and mural galleries with loopholes were not popular features in Russia at that period. In the mid 15th century loopholes began to appear at the foot of walls; however, these were still rare. Fire was generally effected only through the crenellations of a battlemented parapet. The top of a wall was reached by stairs inside the towers or by ladders fixed to the wall.

The boevoy hod (wall-walk) of Porkhov fortress. In Russian fortresses these were covered with gable roofs, to protect against the weather.

Stone walls by no means replaced wooden ones outright. The latter continued to prevail in fortifications. To complicate matters, the wooden walls, unlike stone ones, have not been preserved, which may give the wrong impression as to the scale of their extent. In the 14th and 15th centuries wooden walls were modified due to the development of stone-throwing engines and cannon. They became thicker, consisting not of one but of two or even three rows of logs with earth or rubble filling in between. The most common type of wall now comprised one or two rows of log cells closed on all sides, with their ground floor filled with earth or rubble. This structure had been encountered earlier (from the 10th century onwards) but only became widespread in the 14th–15th centuries.

Gates in Russian fortresses were placed in gate-towers as a rule. Primitive fortifications might have a gate that was cut out of the wall, much like a common household gate. However, in cities or strategically important fortresses gates were always located in gate-towers. In Rus’, no gates have been found in the walls between two flanking towers, with the exception of the late Kopor’e fortress, which was probably built with the participation of foreign craftsmen.

Two views of the Talavski zakhab, Izborsk fortress. This was a narrow passage 36m long and 4m wide. Today the exterior wall of the zakhab lies in ruins.

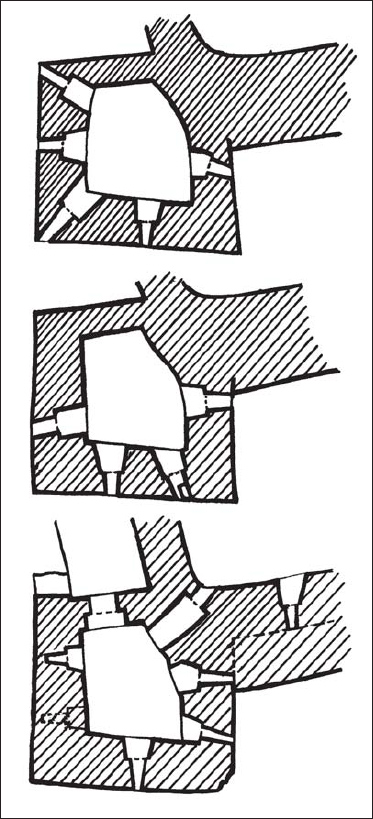

Plan of a vylaz (secret exit) in the wall of Izborsk fortress. A vylaz was made in a wall to allow sorties. A vylaz in a stone wall consisted of a passage inside the wall camouflaged on the exterior with a thin masonry wall that was broken down at the moment a sortie was begun.

Until the very end of the 15th century towers in Russian fortresses narrowed markedly towards the top. For example, the Temnushka Tower in Izborsk fortress, seen here, has a truncated cone in shape. Visible in the foreground are the ruins of the outer wall of the Nikolski zakhab that started at this point.

In the 10th–12th centuries gate-towers were the only towers in a fortress, with the exception of watchtowers, which were rare. The gate in a gate-tower was placed on the same level as the rampart’s base, so the tower itself, sitting considerably below the walls, looked as if it was cut into the rampart, and barely rose above the walls. Nor was the tower designed for flanking fire, leading many researchers to consider it an unusual form of a gate rather than a tower, and that in fortresses of the period there were no towers whatsoever. It should be noted that chroniclers are of the same opinion: gate-towers were merely called gates, not towers.

These gate-towers were mostly made of wood and covered with hip roofs (i.e. roofs with four or more sloping sides). It was only in the large cities like Kiev or Vladimir that gate-towers were made of stone or brick. Here, in addition to their military function, they served as triumphal arches symbolizing the wealth and greatness of the city, and were often embellished with decorations. In Kievan Rus’ a tradition began of accommodating a small chapel in gate-towers, which served no defensive function; or sometimes an icon was placed above the gate instead. Chapels and icons were believed to secure ‘heavenly protection’ for the town. This tradition survived in Russian fortifications until quite recently, such as in the Siberian ostrogs of the 18th–19th centuries.

Interior view of the Malaya Tower of Porkhov fortress. The exit onto the walls here is on the rear side of the tower, on the level of the wall-walk. There would be a temporary wooden platform here, which could be easily destroyed in the event that the enemy seized the wall.

While prior to the 14th century the gate was usually placed on the mainland side, after this it was built on one of the sides less vulnerable to attack. The gateway in earlier fortresses, and later on in minor ones, ran perpendicular to the rampart. From the 12th century onwards, however, parts of the rampart flanking the entrance were sometimes shifted, so that the gateway ran parallel to the ramparts. As a result the enemy would find themselves trapped in a narrow passage between the ramparts. In the 14th and 15th centuries this idea developed into an intricate gate complex called a zakhab. This was a long, narrow, often winding corridor between walls, where the enemy found themselves under cross-fire. The zakhab usually had two gates: one at the entrance and the other at the exit from the corridor, with the outer gate at a right angle to the inner one where possible. In many cases the zakhab was additionally strengthened with a tower placed next to the outer gate, or above one of the gates, or in the middle of the zakhab corridor. Zakhabs could be present in both stone and wooden fortresses. The remains of stone ones can be found at Izborsk, Ostrov, Porkhov and Pskov.

Loopholes in the Vyshka Tower. This was one of the four circular towers of Izborsk fortress, which were built in the late 14th century and modernized in the early 15th and then early 16th centuries. The loopholes are clearly arranged not one above the other but in a ‘chessboard’ fashion, to eliminate dead ground. On the left, between the storeys, are three square sockets left by the beams of the ceiling.

The arrangement of loopholes in the ground, first, and second storeys (tiers) of the Talavskaya Tower in Izborsk fortress. Note that the arrangement of the loopholes is not repeated. They all face different directions, thus commanding every area in front of the tower.

From the 14th century onwards gates were provided with portcullises, usually made of iron although examples survive of wooden ones with iron facings.

In some fortresses there were also secret exits (vylaz) used by the defenders to make surprise sorties. The vylaz in a timber-and-earth fortress took the form of a boarded tunnel built through a rampart with a disguised exit on the outside. In a stone fortress, they took the form of a passage in the wall with the exit concealed behind a thin layer of masonry. The masonry could be easily smashed through to make a sortie and then replaced later. The remains of vylaz can be seen in the fortresses of Izborsk and Porkhov.

A bridge in front of a gate was usually narrow, and built on permanent pillars. Up to the 15th century all bridges were wooden and could easily be destroyed following news of the approaching enemy. A bridge could sometimes be turned into a trap as, for example, in 1426 in Opochki, where the defenders let the assailants seize the bridge only to bring it crashing down into a ditch filled with sharpened stakes. The mid 15th century saw the first stone bridges built in Rus’, and at the end of the 15th century drawbridges first began to appear.

Up to the mid 13th century there were practically no towers in Russian fortresses apart from the gate-tower, and one or two other towers at most. The second half of the 13th century saw a growth of free-standing towers in the fortresses of the Galich-Volhynia principality, which came under the influence of its western neighbours Poland and Hungary. These towers were placed inside the walls and near to the side of the fortress most vulnerable to attack. They served concurrently as watchtowers, a second line of defence allowing fire to be brought to bear upon the assailants, as points for directing defensive operations, and as the place of final refuge if the enemy broke into the fortress. While all the other fortifications were wooden, these donjons were often built of stone or brick. Examples still survive at Berestie, Kamenets, Stolpie, and Czartoryisk. The tower in Berestie was virtually square at the base (5.9m × 6.3m) with walls 1.3m thick. Kamenets has a circular brick tower 29.4m high, 13.5m in diameter, and with 2.5m-thick walls. In Stolpie the tower is of stone, 20m high, and rectangular on the outside (5.8m × 6.3m) but circular inside (about 3m in diameter). The round tower in Czartoryisk greatly resembles that of Kamenets.

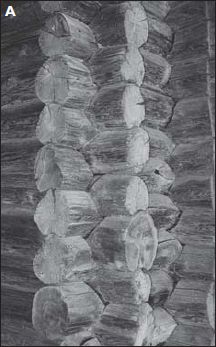

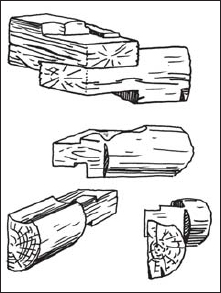

Ways of joining log ends: ‘v oblo’ (A) and ‘v lapu’ (B). The first way, with log ends sticking out, was more popular in log cell walls, while in wooden towers both ways were used. The ‘v lapu’ way was preferred in polyhedral towers as it facilitated the joining of logs at angles greater than 90 degrees.

The 14th and especially 15th centuries saw the number of fortress towers increase rapidly, and they now played an active part in the defence. They were extended beyond the line of the walls to allow flanking fire along the adjoining curtain walls. The increased use of cannon enhanced their importance, as it was here, and not on the walls, that cannon were originally mounted. Towers were still usually sited on the most vulnerable, mainland side.

Stone towers could be rectangular, circular, or semi-circular (known as persi), while wooden towers were rectangular or polygonal (hexagonal or octagonal). Circular and semi-circular stone towers are supposed to have been better suited to conducting sweeping fire and better at withstanding direct hits than rectangular ones, whose corners were easily damaged. Nevertheless, from the 14th and 15th centuries onwards even newly built fortresses were still provided with rectangular towers alongside circular and semi-circular ones. Although the latter became more numerous, they did not fully replace the former, which is evidence of certain advantages held by rectangular towers. It is interesting to note that even in a single fortress towers were never identical; their height and footprints differed widely.

A fragment of an oak tower of the Moscow Kremlin of 1339–40 and the method of joining logs in it. The logs are joined ‘v lapu’, that is with their ends not sticking out. Special grooves and projections were made at the intersections to provide greater strength (they can clearly be seen in the right-hand illustration). The angle between the logs is 135 degrees, which indicates that the tower was octagonal. (Historical Museum in Moscow)

One of the walls in Gdov fortress, made of alternating horizontal layers of two sorts of stone (boulders and limestone).

Towers dating from the 13th to 15th centuries are narrower towards the top. Moreover, their walls are sometimes slightly curved so that they often resemble inverted cauldrons.

Rectangular towers in Rus’ were never built open on the inside (i.e. three-sided). Only semi-circular towers were open. Both open and closed towers had their own specific advantages. Open ones allowed the defenders in the citadel or donjon to shoot any soldiers who turned traitor inside the towers, or to easily push the enemy out of an occupied tower. On the other hand, a closed tower could be turned into an independent centre of resistance in case the enemy seized part of the fortifications. In Rus’ preference was given to the closed tower.

Both wooden and stone towers were multi-tiered. The number of storeys varied from two to six but usually was three or four (including the ground floor). The storeys had beamed ceilings and the holes for the beams can still be seen in stone towers. Movement between the floors was via wooden stairs or sometimes ladders; the latter were pulled up in times of danger. As a rule, the upper floor of wooden towers had an overhanging projection (oblam), which allowed fire to be brought to bear on the enemy at the foot of the tower. Towers had wooden hip roofs. The lower part of the roof usually had a gently sloping pitch conducive to draining water off the tower walls. Hip roofs on towers were often topped with a watchtower (sometimes equipped with a bell) where a sentinel could keep watch. This watchtower was, in its turn, covered with a smaller hip roof, itself crowned with a weathervane. Towers open on the top were extremely rare.

A wall-walk (boevoy hod) ran through one of the storeys of the tower, usually with two doors allowing access to it – although from the point of view of defence this was not ideal, as a wooden door was easy enough to destroy. An improvement to this was an exit on the rear side of the tower leading to a small wooden platform connected to the boevoy hod on the walls. The platform was temporary and could be quickly destroyed, considerably hampering the enemy.

Towers could be called stolp, vezha, kostyor, or strel’nitsa. A stolp was a tower not connected with the fortress walls but was free-standing, as per the donjons in the Volhynia fortresses. A tower was called a kostyor in the Pskov and Novgorod lands and a strel’nitsa in the Moscow district. Vezha was a general, commonly used term. The word bashnya replaced all these terms in the 16th century and has remained in use ever since.

Decorations on the Vyshka Tower and the adjoining wall, Izborsk fortress. Various kinds of crosses and elegant designs as well as round rosettes were characteristic elements of Russian fortification decor.

All the storeys of a tower (often including the ground floor) were provided with rectangular loopholes, both narrow (for arrow shot) and wide (for cannon); in contrast, loopholes were rare in walls in the period under discussion. Tower loopholes were arranged fan-shaped, with loopholes in different storeys facing different directions, aimed at eliminating dead space. The 14th century saw some loopholes with box-rooms on the inside, however these did not become widespread until the 15th century when pechuras, as they were known, began to be used for cannon. Disguised loopholes, concealed behind masonry on the outside, are today rare and unlike those blocked up later they were created at the time of the tower’s construction. Disguised loopholes were probably designed to surprise the enemy; the thin front wall could be easily broken down and fire brought to bear on the enemy at an unexpected angle.

Logs in wooden cell walls were generally joined ‘v oblo’, that is with the ends of the logs sticking out. This method was used alongside the ‘v lapu’ method, without the ends sticking out. The latter was particularly suitable for polygonal towers where the angle between logs was over 90 degrees. This method of joining logs can be seen on a discovered fragment of a tower of the Moscow Kremlin built of oak wood in 1339–40. The angle between the logs is 135 degrees here, which allows us to assume that the tower was octagonal. The logs featured special grooves and notches where they were joined together, making a very solid structure. With an intra-rampart framework, the wooden wall was usually its extension. Otherwise, a wall was generally erected on piles driven into the rampart.

Stone walls were laid with clay or mortar, never dry stone. The structure of the wall resembled a sandwich, with a layer of soft or crushed stone mixed with mortar placed between two layers of hard stone. Monolithic construction methods were much rarer. Some stone walls had a stratified structure, consisting of horizontal rows of various kinds of stone. The walls of Gdov fortress offer a vivid example of this, with rows of boulders alternating with rows of limestone. The walls and towers of stone fortresses often featured symbolic crosses, elegant girdles laid in triangles or diamonds, and round rosettes.