Some 1,500 fortified Russian settlements can be traced to the territories of modern Russia, Belarus, Ukraine, and Poland. Some fortifications have been fairly well preserved or reconstructed, others are only represented by grassy ramparts. Only the defences of the most important cites, the best-preserved fortresses, and the most interesting fortified settlements are (briefly) described below. The names of countries and sometimes districts are given in brackets to make it easier for the reader to locate the gorodishches on a map.

Belgorod (Belgorodka village, Kievan district, Ukraine)

The fortress was built in 991 to protect Kiev from nomadic raids. The gorodishche, comprising a detinets (citadel) and okol’ny gorod, is encircled by ramparts up to 5m high and up to 12m thick at the base. The ramparts are strengthened with an intra-rampart framework of oak log shells, mud-brick, and clay.

Borisov-Glebov (Romanovo-Borisoglebskoe gorodishche, Vakino village, Ryazan district, Russia)

First mentioned in the annals of 1180, it grew up on the site of an Iron Age settlement. Semi-circular in shape, the gorodishche is surrounded with three lines of ramparts and ditches and a side bordering the river.

Czartoryisk (Ukraine)

Ruins of a circular donjon-tower built in 1291.

Dmitrov (Moscow district, Russia)

The city was founded by Prince Yuri Dolgoruki in 1154. Its formidable ramparts survive.

Galich (Krylos village, Ivano-Frankovsk district, Ukraine)

The village houses a colossal gorodishche – the remains of Galich, capital of the Galich and later the Galich-Volhynia principality. Defences first appeared here as far back as the 10th century but the major fortifications were raised in the second half of the 12th century. The detinets (citadel) was protected on the mainland side by two rows of ramparts and ditches. Log walls crowned the high ramparts. The okol’ny gorod was encircled by as many as four lines of ditches and ramparts, the latter surmounted with wooden fortifications.

Gdov (Pskov district, Russia)

A stone fortress was founded here in 1431. The walls, made of alternating layers of boulders and limestone, were 4.3m thick, about 8m high, and 850m long. The fortress was provided with three gates with zakhabs, and with three towers. The gates and the towers do not survive and the height of the walls does not surpass 5.5m today.

The ruins of the walls of Gdov fortress. Their height is no more than 5.5m now. Built of alternating horizontal rows of boulders and limestone, this type of fortification is fairly rare.

The ramparts of the gorodishche of Kideksha, a small castle built in the 12th century on the site of an earlier settlement. The white-stone church of St Boris and St Gleb was also built in the 12th century and is one of the oldest buildings of this kind in north-eastern Rus’.

Izheslavl (a village in Ryazan district, Russia)

Only ramparts and ditches are left of the fortified settlement laid waste by Mongols in 1237. It was once protected on three sides by three rows of ramparts and ditches. A detinets only 20 × 30m in size stood in a corner of the settlement protected by ramparts.

Kamenets (Belarus)

A five-storey (ground floor included) brick donjon built between 1271 and 1288 is well preserved here. It is the best surviving example of the characteristic towers of Volhynia.

Kideksha (a village 4km from Suzdal, Russia)

There are earthen ramparts and the white-stone church of St Boris and St Gleb still to be seen in the gorodishche (supposedly the residence of Prince Yuri Dolgoruki). The fortifications and the church were built in the 12th century.

Kiev (Ukraine)

A settlement existed here as far back as the Iron Age. In the 6th and 7th centuries there were several fortified Slavic settlements on the territory of the modern city. In 989 Prince Vladimir had the old defences levelled to the ground and new, much more formidable fortifications were raised to encircle an enlarged area. The new fortified centre, called ‘Vladimir’s city’, was surrounded with ramparts 16m high and 9–13m thick at the base. The ramparts had an intra-rampart wooden framework and were topped with whitewashed wooden log walls. Four gates, some of them of stone and brick, led into the city. Even more formidable fortifications were raised in Kiev in the early 11th century by Prince Yaroslav. The protected territory (‘Yaroslav’s city’) was seven times larger than ‘Vladimir’s city’ and adjoined the latter on the south. The fortifications comprised powerful earthen ramparts (up to 16m high and 25–30m thick at the base) with wooden intra-rampart framework. They were topped with wooden log walls and stretched for 3.5km. Four stone or brick gates led into ‘Yaroslav’s city’, the most famous being the Great (Golden) Gate. Before the invasion of the hordes of Batu Khan no other fortifications in Rus’ could rival those of ‘Yaroslav’s city’. Remains of the gigantic ramparts of ancient Kiev can be seen today in the centre of the modern city. The Golden Gate with the adjoining sections of wooden walls was reconstructed in 1982.

Kleshchin (Gorodishche village, near Pereyaslavl-Zalesski, Russia)

A small (55 × 80m) fortress sat on a hill called Alexander’s Mount with an unfortified settlement nearby. The fortress was encircled by a rampart topped with wooden walls. The ramparts are 3–8m high today.

Ladoga (Staraya Ladoga village, Russia)

Only fragments of walls of the stone fortress of 1114 survive, as in the 1490s the fortress was considerably modernized.

The rampart and ditch of Mstislavl. This settlement, roughly circular in plan, was probably a prince’s castle. Today trees grow on top of the rampart, which was once topped with wooden walls.

Lutsk (Ukraine)

The brick walls and the towers of the citadel of the so-called Verkhni Zamok (Upper Castle) are well preserved. They were built in 1289–1321 on the place where the older wooden walls were destroyed in 1259 in compliance with the Mongols’ order. The fortifications underwent modernization from 1430 to 1542. The fortifications of the okol’ny gorod, the so-called Nizhni Zamok (Lower Castle) – a rampart, a ditch, and a stone wall of the second half of the 14th century – survive in fragments.

Moscow (Russia)

Hardly anything is left of the fortifications of the Moscow Kremlin of the 12th–14th centuries. The kremlin we can see today was built in 1485–95 and rebuilt later (see Fortress 39: Russian Fortresses 1480–1682). Out of several gorodishches of the period in question discovered on the territory of the modern city, Dyakovskoye gorodishche on the site of Kolomenskoye Park is the one that is best known and most explored. It gave the name to an entire culture of the Iron Age – the Dyakovskaya Culture (the 8th–7th centuries BC to the 6th–7th centuries AD). A settlement existed on this site in the late 1st millennium BC through the 6th–7th centuries AD. The original defences (a rampart and a ditch) were modernized at the turn of the 11th/12th century when the gorodishche became a feudal castle.

A 220m-long section of the rampart is all that remains of the fortifications of Pereyaslavl-Ryazanski, capital of the Ryazan principality from the mid 14th century. With wooden walls surmounting the rampart even the domes of the churches were not visible from beyond the fortifications.

Mstislavl (Gorodishche village, about 10km from the town of Yuriev-Polski, Russia)

A rampart and a moat survive of the fortifications of a settlement founded in the second half of the 12th–early 13th centuries. The rampart strengthened with an oak intra-rampart structure reaches 6m in height and 32m in thickness at the base. The settlement was nearly circular in plan and was probably a prince’s castle.

Pereyaslavl (now Pereyaslav-Khmelnitski, Ukraine)

Within the confines of the modern town of Pereyaslav-Khmelnitski there is a colossal gorodishche – the remains of the once great city of Pereyaslavl. Pereyaslavl’s fortifications comprised a detinets and an okol’ny gorod; both were enclosed in a high rampart, strengthened with an intra-rampart wooden structure, and topped with a wooden wall. A wide and deep ditch ran in front of the rampart.

Pereyaslavl (Pereyaslavl-Zalesski, now Pereslavl-Zalesski, Russia)

The city was founded by Prince Yuri Dolgoruki in 1152. Its fortifications consisted of formidable ramparts. Based on wooden cells and topped with wooden log walls, they were 2.35km long. The ramparts are well preserved and even today are imposing: they are 10m high and 30m thick at the base.

Poyarkovo (a village in Ryazan district, Russia)

Opposite the village, on the other bank of the River Zhraka, lies a gorodishche of the 12th–13th centuries. It was protected by three rows of ramparts and ditches. The innermost rampart goes along the entire perimeter of the settlement, while the two outer ones run down the riverbank and stop at the river. Today the ramparts are 7m high and the ditches are 2m deep.

Ryazan (Pereyaslavl-Ryazanski, Russia)

Earlier known as Pereyaslavl-Ryazanski, the city became the capital of the Ryazan principality in the mid 14th century. In 1778 it was renamed Ryazan. The city’s kremlin was enclosed by a strong rampart topped with oak walls. The fortifications were modernized up to the mid 17th century. Only a 220m-long and 12m-high section of the earthen rampart survives. Gorodishche Staraya Ryazan (Old Ryazan), the remains of the old capital of the Ryazan principality, is to be found 65km south-east of modern Ryazan.

Stolpie (Poland)

Ruins of a rectangular stone donjon of the 13th century can be seen here.

Suzdal (Russia)

The city was first mentioned in the annals of 1024. One can see the ramparts of the detinets today: they are 1.4km long, 3.2–8.5m high and 35m thick at the base. When built under Vladimir Monomakh at the turn of the 11th/12th century, they were up to 10m high and topped with wooden walls. In the late 12th and the second half of the 15th centuries the ramparts were strengthened and built up with earth. The year 1677 saw a new pinewood wall with 15 towers and gates built on top of them. However, all the wooden fortifications burned down in the fire of 1719.

Tustan (1km to the north-east of the village of Urych, Lvov district, Ukraine)

The most famous of the rock fortresses of Galicia. In the 13th and 14th centuries an earlier settlement known from the 10th–11th centuries was turned into a powerful fortress. Its citadel (called Kamen or ‘Stone’) sat on a small ground between four rocks towering 51m above the valley. The citadel comprised five-storey (ground floor included) living quarters and wooden log defensive walls with towers about 15m high. The storeys were connected by a complex system of passages and stairs. A stone wall was raised on the southern side. A possad protected with ramparts, ditches, and wooden walls lay at the foot of the citadel on the slopes of the mountain. A stone-paved road leading to the gate of the citadel ran along the bottom of the ditch. One kilometre from the city, on the rocks of the Ostry Kamen (Sharp Rock) and the Malaya Skala (Small Rock), there was a watch post suited to carrying on independent defensive activities: wooden walls protected the approaches to the rocks and a tank 2m in diameter and 8m deep was placed on the top of the Ostry Kamen.

Vladimir (Russia)

The city was founded by Vladimir Monomakh in 1108. Large-scale construction work was under way here in 1158–65. By the end of the 12th century Vladimir had four sites protected by walls: a detinets, Monomakh’s city (the Middle City), and two fortified possads on the latter’s sides. The detinets was encircled in rather thin (1.0–1.7m) stone walls. All the defences with the exception of the walls of the detinets and several gates were of timber and earth; they consisted of a ditch and a rampart surmounted with a wooden wall. The ramparts were about 8m high and 24m thick at the base. Some sections of ramparts and the famous stone Golden Gate survive now, although the latter has undergone considerable modernization.

Yuriev-Polski (Russia)

A 1km-long rampart surrounded a town nearly round in plan. Preserved from the 12th century, the rampart is 7m high and 12m thick at the base.

The ramparts and ditches are all that remains of the fortifications of Suzdal built by Vladimir Monomakh at the turn of the 11th/12th century.

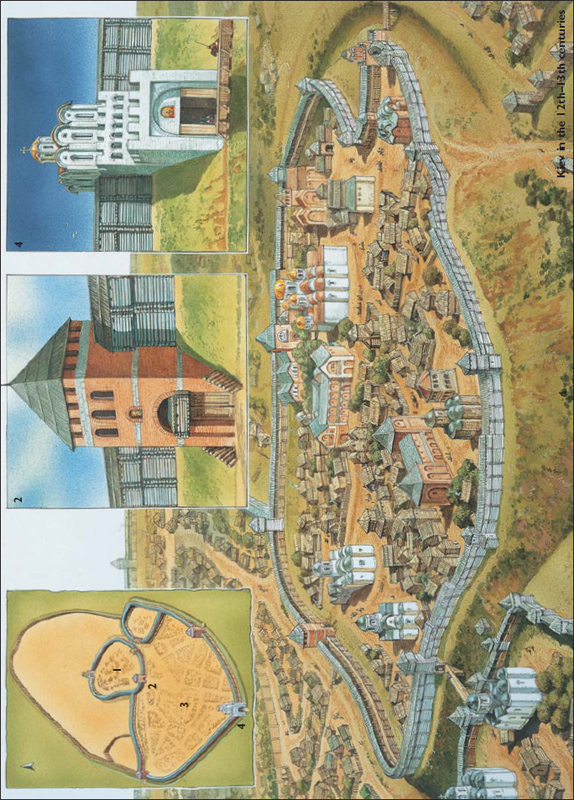

Kiev in the 12th–13th centuries

The main part of this illustration shows a general outlay of Kiev’s fortifications (after P. P. Tolochko). In 989 Prince Vladimir fortified the central part of the city thus creating the so-called ‘Vladimir’s city’ (1). The fortifications consisted of formidable earthen ramparts topped with whitewashed wooden log walls. Among the four gate-towers the St Sophia Gate (2, after Yu. S. Aseev) was notable, being the first gate in Rus’ built of brick and stone, not of wood. Under Prince Yaroslav the southern part of the city saw itself encircled by strong fortifications and acquired the name of ‘Yaroslav’s city’ (3). Until Batu Khan’s invasion these fortifications were the most powerful in Rus’. They comprised 3.5km of huge earthen ramparts provided with wooden intra-rampart structures and topped with wooden walls. Out of the four gates the Golden Gate (4, after S. A. Vysotski), which served as a model for similar gates in other Russian cities (for example, in Pereyaslavl and Vladimir), is worth a special mention. The height of the gateway arch exceeded 12m and its width was almost 7m. The gate shutters were made of oak, forged with iron and bound with leaves of gilt copper. The gate was topped with a church, which had a golden dome. The building of the fortifications of ‘Yaroslav’s city’ took 15–20 years, and was completed by 1037.