I am an Iceni girl. That’s the name of our tribe, the British Iceni. We live in the wild, wide lands in the east of the country. We have lived in this land for always, I think. We were here long before the Romans. It’s our land, not theirs, whatever they say.

My name is Kassy and I am ten years old. Finn, my brother, is three years older than me. My father is the man with the golden beard. He has golden hair too, but his head is shiny bare in the middle. He says that’s my fault, for asking too many questions. Too many questions have made my father’s hair slide off his head.

I live in a big round house in the middle of our village with Finn and my father and my Uncle Red and my grandmother. Uncle Red and my father built the house together and it is the biggest in the village. Uncle Red and my father are the village leaders, and our house is so big because it’s the place where people come when there are arguments or sickness or other things that need lots of talk. Uncle Red is good at telling people what to do. My father is good at making them laugh. Grandmother says Uncle Red used to be good at making people laugh too, but he gave it up when the Romans came.

Kassy means curly-haired. I was born with curly hair but now I just have tangles. I have tangles down to my shoulders and nobody can comb through them, not even my grandmother, and she can untangle almost anything. Spinning wool, arguments, the meaning of dreams. Honey from the honeycombs in the barley straw hives.

She can untangle the North Star from the star patterns in the sky, but she can’t untangle my hair.

Finn’s name has a meaning too. Finn means the fair one. But Finn is only fair when he is washed. Usually he is brown, brown-skinned and brown shaggy hair, just like his dog Brownie.

Finn and I have a grandmother to look after us instead of a mother. Our mother died long ago, when I was a baby. So then my grandmother had to start all over again.

Poor grandmother! She thought she had finished with wailing babies and wild wobbly little ones who scoop everything into their mouths and cannot be left with the fire. And as soon as we grew up from babies and little ones, we became the children who cause so much trouble. The ones who escape from the fieldwork to go swimming in the river, and creep from their beds at night time to visit the horses in the horse runs.

Finn and me.

I don’t spin wool as quickly as I should and Finn whispered to me that he does not believe in any of the gods. We are not good children, my grandmother says. But my father says we’re good enough for him.

“You are easily pleased!” said Uncle Red, but he winked at me when he said it.

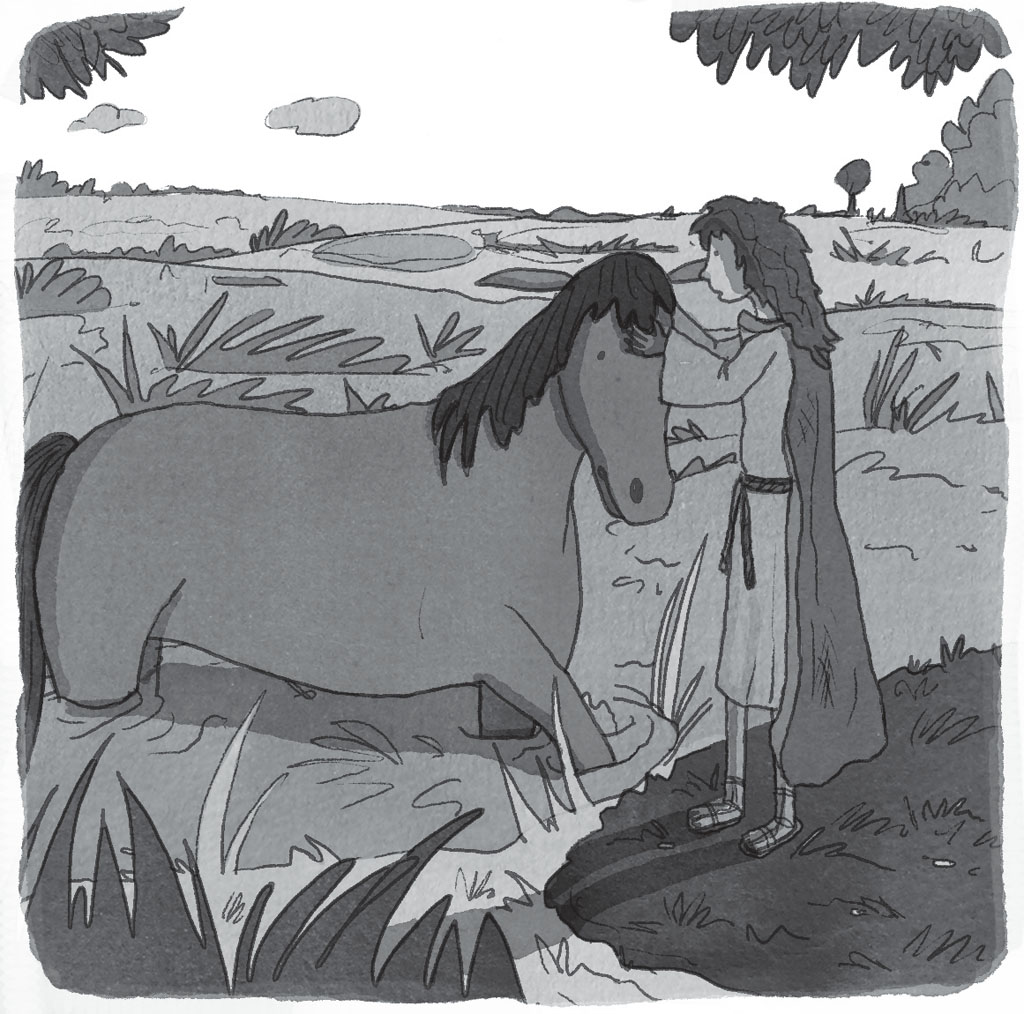

I have a pony. I am the only girl in the village with a pony. I am the only girl my father has ever known with a pony. Perhaps I am the only Iceni girl in the country with a pony. Me! The only one.

“Do Roman girls have ponies?” I asked my father once.

“Not that I know of,” said my father, and Uncle Red, who had heard, exclaimed, “Romans! Oily, murderous, stinking, lying, thousand-cursed thieves!”

“What, even the girls?” I asked, and Uncle Red said probably the girls were the worst of all. And before I could ask what was worse than all the things he had just said, he added, “And your father must have left his wits in the marsh to give a pony to a child like you!”

“Left my wits in the marsh!” roared my father, and he whacked Uncle Red on his shoulders as if he had made a good joke. “Uncle Red! A man of strong thoughts, eh Kassy?” he asked, laughing. “I think he is jealous because I have the only tangle-headed girl in the world with a honey-coloured pony of her own!”

I named my pony Honey when they gave her to me. It’s the perfect name for her. Her coat is dark golden – honey coloured, and her mane and tail are beeswax fair. Her nose is bee-velvet soft.

She comes when I whistle, but not when anyone else whistles, not even Finn.

“She likes you best,” said Finn one morning when we were out at the horse runs with Uncle Red. “It’s not fair!”

“It is fair,” I said. “Because all the other animals in the village like you best!”

Finn didn’t say anything.

“It’s true,” I said. “They do. Even the pigs!”

“The pigs!” shouted Finn so wildly that even Uncle Red laughed at him. “Oh that’s good! Oh that’s wonderful! Am I to ride through the country on a pig then? Did you ever have a sister, Uncle Red?”

“The gods spared me that at least,” said Uncle Red, and he took Finn away with him to help train the chariot ponies. They are bigger than Honey and every shade of shining brown, bright as autumn beech leaves, or as silver dark as oak. Just as pretty as Honey, but I like Honey best.

Honey is nearly three years old now, and as I am not very big or heavy, she is strong enough for me to ride. I do, like a boy, and my grandmother says it’s shocking.

“Shocking!” she says often, but her eyes sparkle when she says it, not shocked at all, and she wove me a riding cloth of green and honey colour and stitched a little sheepskin on the back. She did that to make it soft for Honey when I strapped it on to ride.

“I think if you were a girl you would ride Honey too,” I said to my grandmother once.

“Is that what you think?” she replied. “Well!”

“Well, what?” I asked.

“Perhaps I would,” said my grandmother.

This is how Honey came to be mine.

Our village was famous for its horses. Strong brave little horses with dark shining eyes and long tails to hit the flies away. Clever horses that can find a path in the dark and stand in quietness when you whisper, “Hush!”

But because our horses are clever they are also stubborn. They like to please us, but they like to please themselves too. Sometimes they don’t want to work, and dance away from a halter, just out of reach. Sometimes they lean and lean and push and push on the fences that keep them safe from the marsh.

Sometimes, if we don’t notice that the fence is no longer strong, they push right through.

That’s what Honey’s mother did when Honey was a tiny foal. She leaned against the fence until she pushed a gap and she got out through the gap and Honey followed after. That’s how Honey got lost in the marsh.

The marsh! Our wide, flat eastern land, the Iceni land, is patched with marsh and bog. In places the earth holds so much water that the ground is like thin green porridge. You can set out to walk across good green grass and suddenly find yourself in liquid earth, held together only by the roots of rushes.

Then you are in trouble! Then you need a friend with a rope! Then you’d better not kick or scramble or fight. If you fight the marsh it will fight you back. It will drink you up and swallow you!

Of course, if you are a clever Iceni you will know the paths. You will see how the grasses change to warn you of water under the green. But if you are Roman from over the seas, marching in straight lines with your Roman nose in the air, then in you will go and there you will stay. Even my father, the kindest of men, wouldn’t pull a Roman out of a bog.

I like the marsh. It’s full of little birds. It’s where I go to play when I am tired of grinding the grain to bake our bread, or spinning the wool from the brown Iceni sheep, or cleaning the cooking pots.

I was escaping the cooking pots on the day that I found Honey. Her mother, Little Huff (so called because she liked to huff the dandelion clocks and watch the feathers fly), was calling.

She was calling and calling on the far side of the thorny fence, so deep in reeds and rushes that I only found her by her voice. You cannot follow hoof prints in a marsh, and the reeds are high and springy and close behind you as you walk. It was a wet, tussock-jumping job to find Little Huff. I had to stop and listen, and stop and listen again, but at last I found her, up past her knees in the marsh. When she saw me she tried to struggle towards me, and sank even deeper.

I couldn’t leave her to go for help; I was scared that she would sink even deeper. All I could do was hold her head to stop her panicking, and shout and shout until somebody heard.

For a long time.

Until Brownie, Finn’s dog, came pushing through the rushes.

Brownie is clever. He went and fetched Finn.

Finn fetched my father.

My father fetched Uncle Red.

Uncle Red fetched half the village, ropes and wooden poles and rush mats and barley bread with honey on to coax Little Huff quiet.

It took a long, long time before she would follow the men over the rush mats that they laid for her to walk on, but at last they got her out and she was safe.

Then everyone said, “Where’s her foal? Where’s the foal? Where’s your foal, Little Huff?”

There was no sign of a foal anywhere.

Close to Little Huff the marsh was as blue as the sky. It spread in cool wide pools that had no bottom, only water and muddy water and watery mud.

The men who got Little Huff out told her very kindly that she could have another foal next year and they led her away to the village. But she knew she was leaving her foal behind and she struggled and bit at them. They had such a job making her follow them that they forgot about me. Not even Finn noticed that I had been left behind. He said afterwards that he thought I’d gone ahead to get dry. But I hadn’t. I was standing amongst the tall reeds, a little way off and keeping very still.

I was thinking about the foal. Perhaps I could find the foal like I had found Little Huff. That’s what I was thinking.

It was quiet when the men were gone, except for the birds and, after a while, another sound that wasn’t birds.

Honey, whickering for her mother.

Very carefully I started wading across the blue pools, clutching at the reeds to help me.

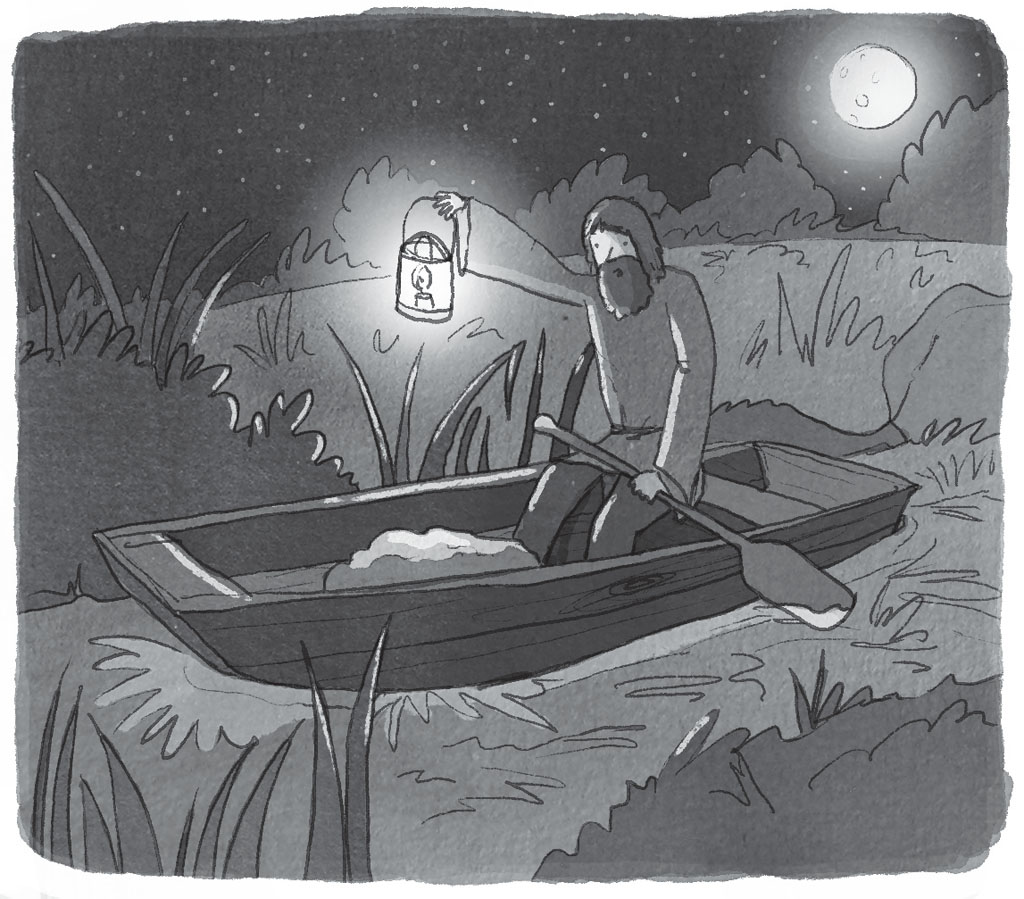

It was after dark when they found us, but Honey was not hurt because I held her all the time and I didn’t let go until Uncle Red arrived with a lantern and the flat-bottomed boat that he used to hunt ducks in the autumn.

Then there was only room for Honey and Uncle Red in the boat, and I had to wait with the water past my middle. It was so cold I could feel my bones hurting.

But Uncle Red soon came back and he tumbled me into his boat and moments later my father grabbed me out of it and wrapped me in his cloak. I stayed wrapped in my father’s cloak across the fields and through the village until we reached the house and the fire. Then hot herb tea with honey in and a great warm fuss.

“What pests these girls are!” said Uncle Red. “The marsh should have swallowed you. Then we’d have some peace!”

But I remembered how quickly he had paddled to me in his little flat boat, calling “Kassy, Kassy, Kassy, I’m here!”

My grandmother got out her best brown pot with leaf patterns on the rim. She said we have to stay friends with the marsh, and that she would give it her pot in the morning, since it had given me back to her.

Everyone nodded, and my father put a coin in the pot too, and then other village people put things in. A handful of grain. A lump of beeswax. An amber bead. Even Finn put in his lucky red bean. “Just in case,” said Finn. He said he’d have rescued Honey himself, if he’d been there, only better and quicker and he’d have used a boat.

Uncle Red put a coin in the pot too, and he said if I was his daughter he would beat me with a willow wand, but as I wasn’t his daughter he would settle for a hug.

So I did hug him. And Father and Grandmother and Finn. I was so pleased to be out of the cold lapping water, and the sucking grip of the mud. I was glad my grandmother thought of giving the pot to the marsh! It made me feel safer.

Before I went to sleep that night my father said Honey was mine, for ever and ever.

That was the best day of my life. It happened more than two years ago and often, just before I go to sleep, I tell it to myself like a story.