Every morning the first thing I do is rush outside to see Honey. She lives in the horse runs on the far side of the village. My father is usually there before me, watching.

“You can learn a lot about horses, just by watching them,” he says.

We stand side by side and are quiet as they harrumph together or dance away from a shadow or go silent, gazing at something we cannot see.

“Don’t you wish you could understand what they are thinking?” I asked my father once.

He looked down at me as if I had said something quite astonishing.

“Of course I understand what they’re thinking!” he said.

“What then?”

“Those two know I’ll take one of them for training and they’re wondering which. Little Huff saw a bank vole that a weasel had startled. That one gazing is thinking of her foal.”

“She hasn’t got a foal.”

“Her foal is a month away. A month and a day and it will be running beside her!”

“What is Honey thinking?” I asked.

“She’s wondering when you’ll give her the salt that you are hiding in your hand!” said my father.

“How did you know I had salt in my hand?”

“Honey told me, of course,” he said, and laughed at my surprise.

Our village’s horses are fit for a queen, that’s what we say, and it’s true.

Fit for an Iceni queen, fit for Queen Boudica. She came here last summer to look at the bright brown chariot ponies that she always likes the best.

The whole village got ready for that day. The big well was cleaned and the street was swept. Green bracken was piled over the smelly middens where all the village rubbish gets dumped. The children were washed and Uncle Red went from house roof to house roof, patching the thatch. And when Queen Boudica arrived the sky turned twice as blue and the sunlight twice as bright and we took her and her people down to the horse runs in a great chattering crowd.

Queen Boudica was beautiful that day. Her gown was red and her cloak was green and her hair was fiery gold and piled up her head with combs to hold it in place. When the wind caught her cloak she gathered it up and I saw she was wearing gold sandals.

Gold sandals out to the horse runs!

“Ahhh,” I breathed, and I laughed out loud because they were so pretty.

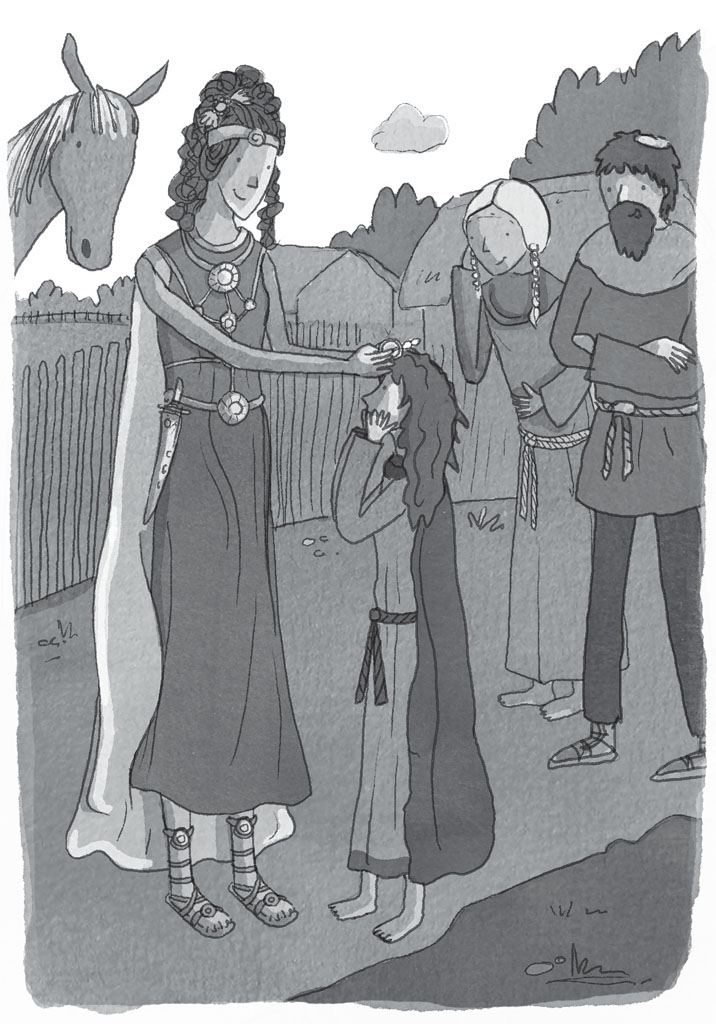

Queen Boudica heard me laugh. She looked down at my feet, which were washed but bare, and she looked up at my hair that was blowing in my eyes and then from her own bright hair she took a bronze comb and beckoned me to come close.

Queen Boudica fixed her comb in my tangled hair and then she laughed and I laughed and everyone laughed and Finn’s dog Brownie bit off the dog-daisy wreath I had put round his neck and tossed it up in the air.

That’s what happened the day I met Queen Boudica and afterwards my grandmother untangled the comb from my hair and held it close to her cheek before she put it in a little soft bag to keep it safe for ever.

“You lucky, lucky girl,” she said.

“Why is Kassy lucky?” asked Finn.

So then we found out that Finn had missed the whole thing, even when Brownie threw the daisies in the air.

“Too busy staring at the Queen’s princesses,” said my father. “Which one was it, Finn, the gold or the silver?”

“Silver,” said Finn, bravely (although he blushed bright red).

The gold princess was the eldest. She was bigger than me. She was as bright as her mother with the same quick laugh and swift step. Her sister was smaller. She wasn’t really silver, but her hair was barley-straw silvery pale and her eyes were silvery grey. She’d fed bread to the horses (which I am not allowed to do) and her face had shone when they nudged her hand for more.

But both princesses were lovely. Gold and silver and lovely.

“Well, why not?” asked my father, hitting Finn between the shoulders almost as hard as he hits Uncle Red. “Why not a princess in the family, eh Red?”

Uncle Red is not a man for talking much about princesses. He rolled his eyes and put his old work tunic on and said he’d been meaning to shift the dung heap for days and Finn could help if he liked.

I love Uncle Red but I can see why no one married him.

Uncle Red is older than my father. He can easily remember the time before the Romans came.

Nobody wants the Romans. Everyone grumbles about them, and detests them, and tells bad stories about them. But Uncle Red acts like every Roman that ever stepped is his own private enemy. They are always on his mind.

The Romans came to our country and they took our towns and they took our land and they took our tracks and made them roads. They marched along those roads in tens and hundreds, and hundreds and more. Armed and smart and ruthless. Some British tribes gave up to them at once, but not the Iceni.

The Iceni never gave up, but still they had to bargain. They had to bargain, or lose everything: the villages and horse runs and fields and Queen Boudica’s rule of her people. They had to give up their weapons, and they have to pay the Romans. Tax collectors come to the village. We pay them in coins and horses and anything else that catches their greedy eyes. Last time they took my grandmother’s new woven blanket. Food, they like, corn and honey.

But there are ways of making things a little better.

“Pity the poor Roman,” says my father, “he’s never eaten a honeycomb that some Iceni has not spat on.”

The Romans don’t stay long near a well-stirred midden either, and the dogs that we tied when Boudica came are not tied when the tax collectors arrive.

My grandmother and my father and my Uncle Red and Finn all say the same thing: “There are no good Romans.”

They are wrong. There is one. Not very long ago I met a good Roman and it was because of Honey.

The bigger Honey grew, the prettier and cleverer she became, the more I was afraid of the tax collectors. What if they saw Honey and said, “I’ll have her.”

The last time they came I was so afraid I hid her.

At the end of the village is a broken old house. It caught fire, like thatched houses often do. Uncle Red patched the burnt thatch but it still smelt bad inside. It came to be used for storing things – wood and an old plough, and a few worn grinding stones. Things like that. That was where I took Honey to hide her and I put mud on her to make her look less lovely than she was. It didn’t work very well. Anyone could see that underneath she was shining gold, but I did it anyway. Then I led her into the darkest part of the old house and stayed there with her with my face against her neck. I whispered to her to keep her quiet, “Hush Honey, hush Honey, Honey, Honey, hush!”

When I looked up a Roman tax collector was watching me.

Sometimes the tax collectors speak our language, sometimes their own. This lot spoke ours.

Outside one of them called, “Anything in there?”

Then the Roman watching me smiled and put his finger to his lips and he called back very clearly to make sure I heard, “Nothing in here. Just a little dirty honey!”

And then he was gone.

One good Roman.

When I told about it afterwards nobody would believe me. They didn’t even want to listen. “Stop that talk!” said Uncle Red, so fiercely that I did.

I stopped talking, but I didn’t forget. Whenever I notice the empty house I remember and I smile.