WHAT THE GOP VICTORY IN 2010 HAS TO SAY ABOUT LATINO POLITICAL POWER

The story of the 2010 midterm election was dominated by the Tea Party, the Affordable Care Act (ACA), and the sweeping Republican victory that emerged. The GOP took control of the House of Representatives and numerous state legislatures and gubernatorial offices in a variety of states, including Michigan, Wisconsin, Ohio, Florida, and Pennsylvania, as well as in heavily Latino states like New Mexico and Nevada. On the face of it, the 2010 election would appear to refute our central claim—that given the current distribution of policy and party preferences and the issue agenda of the GOP, Latino population growth is moving the country relentlessly toward the Democrats and their candidates. The results from 2010 compared to those from 2006 would appear to make this claim for Latino electoral influence specious on its face. Political observers would be quick to suggest that Latino voters didn’t make a difference in 2010.

They’d be wrong.

First, in 2010 the issue of immigration and the GOP attempts to legislate against immigrants rose to become a primary yardstick—if not the primary yardstick—whereby Latinos judged the GOP. The passage of SB 1070 set into motion the immigration dynamic that defines the Latino-GOP relationship to this day. (We cover this relationship in much greater detail in Chapters 9 and 10.)

Second, the results of the 2010 election, rather than refuting our claims regarding demography, illustrate its increasing importance. The 2010 election varied little from elections before or since in how the electorate responded to the parties. The GOP was able to drive up its share of the vote among whites, while the standard decline in turnout by left-leaning voters, seen in all midterm elections, made that white vote share more determinative.

Finally, Latino voters and the issue of immigration were of pivotal importance in saving the Senate for the Democrats and in other significant elections. In short, 2010 would have been a lot worse for the Democrats without the Latino effect, from the reelection of Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid of Nevada to the election of Governor Jerry Brown in California.

Rather than demonstrating the residual weakness of the Latino voting bloc (and by extension, our argument), the 2010 results laid the groundwork for Latinos’ historic contributions in 2012—and the immigration debate in the 113th Congress.

THE WARM-UP

Before we examine 2010 up close and begin to tell the immigration story—which will be an almost constant subtext for the remainder of the book—we must ask an obvious question: why was immigration almost wholly missing from the story of 2008? The answer is easy: the two major-party candidates (and Obama’s primary rival Hillary Clinton) all held basically the same views on immigration.

More specifically, however, the complete absence of immigration from the 2008 general election was a cross-aisle conspiracy of silence, if you will. John McCain’s support of comprehensive immigration reform in the US Senate in 2007 very nearly derailed his entire presidential campaign. By midsummer in 2007, McCain’s fund-raising was dried up and he was laying off staff. Anti-immigrant rhetoric was ramping up strongly in the GOP at that time, and McCain, long a champion of immigration reform, was on the wrong side within his own party. By the time he made it through to the general election, he had no incentive to raise immigration as an issue.

Why didn’t Obama raise it, then, if the issue had the potential to create such mischief for his opponent? Then-senator Obama believed that immigration was a losing issue for Democrats, and this position was an article of faith among his advisers, Jim Messina, David Plouffe, and David Axelrod. They saw lots of negatives and little upside in engaging in an immigration debate. Though Obama did address immigration during the campaign when asked about it, immigration was not a focus of his message, and it played little role in his public outreach. Immigration was the great unspoken issue in the 2008 general election.

Midterm elections are different from general elections: they are won on party core constituents, not on the part-time voters and ticket-splitters—those with less interest in the political system, weak attachment to either party, and low levels of information—who occasionally turn up for presidential elections but almost never for midterms. The midterm demobilization of the president’s electoral coalition is almost an American tradition.

As the Democrats looked ahead to the 2010 election, they realized that on almost every key issue the president had forsaken a core constituency, either through inaction or in the process of trying to attract and retain moderate and independent voters. Gay and lesbian activists had organized a boycott of fund-raising by the Democratic National Committee (DNC) and Organizing For Action (OFA) because of the president’s inaction on LGBT legislative priorities. Organized labor had worked tirelessly for the Obama candidacy in hopes of achieving a more pro-labor regime, including card-check union organizing elections. What they got for their efforts was a tax on union-quality health care plans. Financial reform advocates were still waiting for the first perp-walk of Wall Street charlatans (who continued to receive taxpayer-subsidized bonuses over little or no White House objection). Civil libertarians got no torture trials or indictments for transgressions of the previous administration associated with the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and the “war on terror” (and none ever appeared), and the prison at Guantánamo remained open. The Democratic base was, to say the least, restless in 2010.

For Latinos, the promise of immigration reform—signaled during the campaign for action during the administration’s first year, then before the midterm election—was as yet unfulfilled. Instead, stepped-up enforcement by the border patrol, including sweeps and raids that targeted working mothers and fathers rather than employers and criminals, were justified with the claim that this was the price of buy-in by those on the right for comprehensive immigration reform. In 2014, as we write this, the same logic is in place.

The collective effect of this rightward drift and frequent inaction by the Obama administration was a shocking enthusiasm gap between Democrats and Republicans, which was documented widely in the blogosphere and elsewhere. Latinos were no exception. When Latino Decisions attempted to estimate this effect among Latinos in a March 2010 poll, we found Latino enthusiasm for voting in an upcoming election at an all-time low.

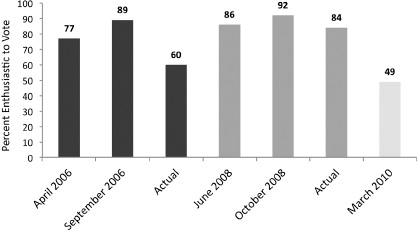

In 2006, when Republicans held the White House, the Senate, and the House and immigration marches mobilized millions of Latinos around the country, interest in the midterm elections was at record levels (Figure 7.1). Four years later, many Latino voters saw no urgent need to turn out. In an April 2006 Latino Policy Coalition survey (which we helped write), 77% of Latino registered voters stated that they were certain to vote, a measure of enthusiasm that grew by September 2006 to 89% who were determined to vote. By that November, about 60% actually voted. In 2008 enthusiasm was higher, but that’s generally true in presidential election years.

Compare those numbers to March 2010, when just 49% of Latino registered voters said that they were very enthusiastic about voting. Since 60% of Latinos turned out in 2006, when their self-reported enthusiasm was 77%, what would that spell for 2010 if the starting point for enthusiasm was only 49%?

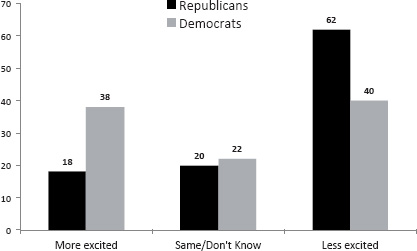

The low enthusiasm for voting mirrored the low levels of excitement about both the Democratic and Republican Parties. When party members were asked how their excitement for their party had changed since January 2009, neither party had close to majority excitement (see Figure 7.2). Republicans in Congress, who made little attempt to reach out to Latinos, continued to suffer a credibility gap—18% of Latinos were more excited about the GOP, compared to 62% who were less excited and 20% who registered no change. Since Latinos nationwide generally reported a GOP partisan identity between 16% and 20%, that excitement number in 2010 should be read as reflecting core partisanship, but the high number for “less excited” suggests that there had been some hardening of Latino attitudes against the GOP, even by 2010.

FIGURE 7.1 Election-Year Enthusiasm for Voting among Latino Registered Voters, 2006, 2008, and Early 2010

![]()

![]()

For Democrats, however, the numbers weren’t much better: 38% of Democratic Latinos were more excited about the party, 40% were less excited, and for 22% there was no change. This significant variation from normal partisan patterns was strongly suggestive of the disappointment level felt by many Latino voters leading up to the 2010 midterms. Perhaps some of the decline in enthusiasm was inevitable—no administration can live up to all voters’ expectations at the time of election. But there were no excuses for the Democrats: from 2008 to 2010, they controlled all three elected branches of national government. Knowing who was in power, Latinos knew where to channel their disappointment—so the Democrats’ numbers were net negative.

FIGURE 7.2 Self-Reported Excitement among Latino Registered Voters about the Two Political Parties, March 2010

![]()

![]()

In March 2010, then, Latino excitement about Democrats and enthusiasm for the 2010 midterm elections was lower than when Obama was elected, and lower than it was for the 2006 midterms. With the stage set for significant declines in Latino turnout, it was an open question, early in that year, whether any event or policy action could restore Latino energy and support for the Democrats.

SB 1070, THE DREAM ACT, AND IMMIGRATION IN 2010

As it has done for a generation, and as it did for Democrats in 2006, the saving moment came over immigration. Republican anti-immigrant rhetoric and policy actions served to poison their brand with Latino registered voters.

On April 23, 2010, Jan Brewer, the elected Republican secretary of state in Arizona who had succeeded to the governorship of that state upon the appointment of Democratic governor Janet Napolitano as secretary of Homeland Security, signed Senate Bill 1070 into law. Dubbed the “papers please” law, the statute included a series of restrictions and penalties on undocumented persons, as well as changes to how law enforcement officials would interact with persons “suspected” of being undocumented. The sweeping elements of the law were subject to multiple legal challenges and widespread opposition by immigrant and Latino advocates.

Latino Decisions polled Arizona’s Latino registered voters just seven days later, on April 30. That poll was the first—and, for some time, the only—poll of Latino citizens regarding their views of the law.

Opposition to the law was widespread and intergenerational. Arizona Latinos whose grandparents were born in the United States—that is, fourth-generation or more—were opposed to the law by more than a two-to-one margin. Among the generations who had arrived in the United States more recently, opposition was even higher. The reason was clear—the vast majority of Latino voters in Arizona believed that ethnicity (racial profiling) would be the mechanism of enforcement. Any Latino citizen and/or legal resident of the United States could conceivably be stopped and asked for identification that would prove that their presence in the United States was legal. Imagine being a fourth-generation US citizen but being legally required to carry your documents with you at all times!

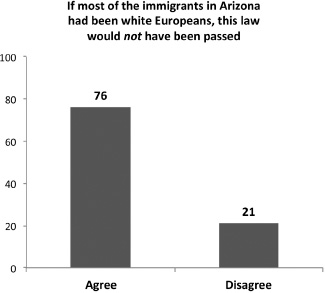

Whether targeted against immigrants or not, SB 1070 imposed a burden on all Latinos through its racial mechanism of enforcement. Over three-quarters of our Latino registered voter respondents believed that the law was explicitly racial and would never have been adopted if most immigrants were white.

The partisan effects of the passage of SB 1070 were immediate. In the minds of the Latino electorate in Arizona, the GOP was overwhelmingly to blame for its passage, which was accurate in terms of the legislative votes in the Arizona legislature. Among Latino voters, 59% held the GOP responsible, compared with just 2% who believed that the Democrats were to blame. However, we’d be remiss if we failed to point out that one-third of Arizona voters (33%) blamed both parties. This, too, had a basis in the legislative record, as several Democrats either voted for the legislation or were conveniently absent for the roll call.

FIGURE 7.3 Latino Registered Voters’ Beliefs Regarding Whether SB 1070 Was Passed Because of the Racial Composition of the Immigrant Population, Arizona, April 2010

![]()

![]()

The second major event on the issue of immigration occurred in September. The administration’s actions had continued to dampen Latino enthusiasm for participating in elections and supporting Democratic candidates, even after Obama’s Department of Justice filed suit to block some of the provisions of SB 1070. The turnaround came in September less than six weeks in advance of the midterm election. On September 21, 2010, Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid, himself facing an uphill path to reelection, brought forward a cloture vote on the DREAM Act, an immigration policy proposal, originally authored by Republicans, that would grant legal status to some undocumented persons who had been brought across the border (or had overstayed their visas) under the supervision of parents or guardians and hence had no culpability in their undocumented immigration status. If such individuals were attending college or volunteering for the military, they would receive legal status. The cloture vote fell three votes shy, 56–43 (with Senator Reid switching his vote to the minority at the last moment for procedural reasons). Of the forty-two sincere “no” votes, forty-one were cast by the Republican minority.

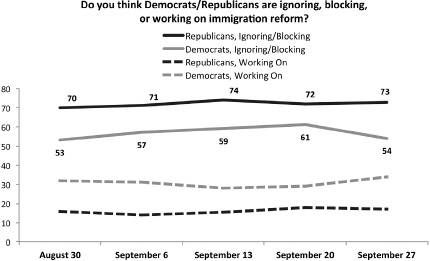

FIGURE 7.4 Latino Voters’ Perceptions of Democratic and Republican Actions on Immigration Reform, August–September 2010

![]()

![]()

When Harry Reid brought the DREAM Act to the floor, Latino Decisions was in the midst of a weekly tracking poll. The data from the poll showed that 77.5% of Latino registered voters supported the DREAM Act amendment, versus just 11.5% who opposed it.

At the same time, the Democrats saw a favorable turn in perceptions that they were working on immigration reform. In the week prior to the vote, our data indicated that 61.1% of Latinos felt that Democrats were either ignoring or blocking immigration reform; that number dropped to 53.8% during the week of the vote. Likewise, the percentage who thought that Democrats were actively working on passing reform went up from 25.7% to 30.8% in one week. This trend, which continued for the remainder of the 2010 electoral season, is illustrated in Figure 7.4.

As a result of the DREAM Act cloture vote, Republicans continued to suffer reputation decline among Latino voters. Just three weeks earlier, our tracking poll reported that 63.2% of Latino registered voters were “less excited” about the GOP—in the wake of the vote, 71.3% were saying that they were “less excited” about the GOP compared to a year earlier. Just weeks before the 2010 election, the GOP brand was heading in the wrong direction among Latino registered voters.

TABLE 7.1 The National Popular Vote Share in NEP Exit Polls, by Race and Ethnicity, 2004–2012

![]()

Source: NEP exit polls, as tabulated by CNN.

Note: Numbers are percentages. The rows do not report votes for third parties and hence may total less than 100. The columns may not add to 100 owing to rounding error.

a. Owing to the particular characteristics of the NEP Latino sample in 2004, and as we have documented elsewhere, Latino Decisions, like most other observers, is deeply skeptical of this number. A better estimate of the Latino vote percentage for Republicans in 2004 is approximately 40%. See Barreto et al. (2005).

![]()

So, with the passage of SB 1070 in Arizona and the Senate’s consideration—and ultimate rejection—of the DREAM Act, how did Latino voters end up voting in 2010? Despite the description of that election as a dramatic GOP victory, the underlying dynamics of the election were very similar to elections before and since. That is, like all American elections, the local elections were won on the margins.

Table 7.1 illustrates the vote by group as reported in the National Election Pool (NEP) exit polls over the last decade of elections. In 2010 the GOP did marginally better among all groups than it did in 2006, largely owing to changes in the composition of the electorate: midterm elections turn out fewer voters of lower income and lower levels of education, resulting in a significant drop in minority turnout. In 2010 non-Hispanic whites constituted 78% of the electorate, compared with 74% two years earlier and 72% two years later. More importantly, those who tend to fall off in midterm years are disproportionately Democratic voters.

In 2010 a substantial majority of whites voted Republican, as they have in every election since 1964. For all other racial and ethnic groups, even with the decline in turnout disproportionately affecting Democratic voters, majorities voted Democratic.

HOW THE WEST WAS WON, 2010 EDITION

Despite the fact that the year started with significant disappointments and frustration with the Obama administration, the passage of SB 1070 by the Arizona GOP and Republican Senate unity in blocking the DREAM Act were sufficient to restore Latino enthusiasm for electoral participation. Latinos were approximately 8% of the electorate in 2010, the same as in 2006 when nationwide immigration marches generated substantial electoral enthusiasm. And though their support for Democrats was diminished compared with 2008—by 3%, the smallest decline in any demographic—in exit polls Democrats still outpolled Republicans among Latinos by nearly two to one. And that was in the exit polls that, as we have argued elsewhere, significantly underestimated the Latino Democratic vote.1 The Latino Decisions estimate, based on our 2010 election eve poll, was a 76% Democratic vote share in the two-party House vote.

So, despite national political trends and earlier disappointments, Latinos voted heavily Democratic in 2010, either two to one or three to one. But did they make a difference?

In four elections—the gubernatorial elections in California and Colorado and the senatorial elections in Nevada and Colorado—Latinos made a critical difference to the outcome, either in terms of actual votes cast on election day or in how the race took shape rhetorically, and usually in both ways.

This is not to say that Latinos did not matter elsewhere. In Illinois, Pat Quinn’s election as governor was a squeaker—he prevailed by 0.3%. Solid Latino turnout and an approximate 83% vote share for Quinn among Latinos contributed a net margin of 4.2%, which was far larger than his actual win. (Latinos were not enough to save Alexi Giannoulias, who lost his Senate race to Republican Mark Kirk). Also, Kamala Harris’s election as attorney general of California would not have been possible without an extremely strong Latino vote.

The Colorado Gubernatorial Race John Hickenlooper was elected governor of Colorado in 2010 with only 51.01% of the vote in a three-way race with GOP nominee Dan Maes and Congressman Tom Tancredo, who ran on the “Constitution Party” ticket. Tancredo, a former GOP member of Congress, has made anti-immigrant politics a hallmark of his political career, and it remains the raison d’être for his career. He bolted from the GOP in that cycle, ostensibly because he believed that neither primary candidate had the political strength to win the general election. Though Hickenlooper received more than 50% of the vote, including a net 6.3% from the state’s Latino electorate, the division of conservative forces no doubt played a significant role in his victory. Nevertheless, the third-party candidacy of the nation’s most outspoken opponent of undocumented immigrants, coupled with the Latino vote share, signaled a critical role for Latinos in the state’s politics.

The California Gubernatorial Race The race to replace California’s termed-out governor, Arnold Schwarzenegger, was unusual, to say the least. The Democratic nominee was previous two-term Democratic governor Jerry Brown, who had returned to political life to serve as mayor of Oakland and as attorney general before running for his old office. The state’s partisan evolution since the 1990s made this an uphill race for any Republican, despite the fact that Brown had shown increasing reluctance to fund-raise, campaign, and the like.2 The conventional wisdom was that the only GOP candidate who stood a chance would be someone like Schwarzenegger—a socially moderate, fiscally cautious candidate with little or no connection to the state party establishment.

Say, someone like Meg Whitman.

At the time, Whitman was the former CEO of eBay and widely respected in corporate and Silicon Valley circles. She had a history of public-spirited action, but not as an elected official. Her business acumen looked to be an ideal selling point in a state that was suffering (at that time) serious fiscal problems. Finally, and most importantly, she had a huge bankroll and a willingness to spend a bunch of it on the election.

In the end, Meg Whitman spent over $140 million of her own money in addition to a sizable sum raised elsewhere. And she lost by 1.3 million votes, 53.8% to 40.9%. How such an attractive candidate could lose by such a large margin deserves explanation. Moreover, Whitman lost to someone with almost no campaign infrastructure and no Spanish-language website.3 Despite the absence of a Spanish-language website, Latinos turned out in droves for Jerry Brown. Latino Decisions’ 2010 election eve poll estimated that Brown received 86% of the Latino vote, which, at 18% of the electorate, meant that Latinos contributed a net 13.1% of Brown’s overall total.

Without Latinos, the race would have been a virtual tie.

There were four reasons for the Latino enthusiasm for Brown. First, several independent expenditure groups ran a sophisticated messaging campaign designed to mobilize support for Brown, even though he had little campaign infrastructure to reinforce the message. Despite the campaign’s paltry efforts, there were Latino-targeted ads in English and Spanish running in most of the state’s media markets, as well as large-scale direct mail and get-out-the-vote phone campaigns.

Second, Meg Whitman got caught using different campaign messages with different audiences. Specifically, while running ads in Spanish saying that she had no interest in Arizona-style anti-immigrant legislation, she was giving interviews to conservative talk-radio and telling a somewhat different story. This was particularly true during the primary, when Whitman was working to put away more conservative primary rivals by touting her opposition to in-state tuition and other state benefits for the undocumented. The juxtaposition of these clearly mixed messages was called out by the Brown campaign and its surrogates as dos caras, or “two-faced.” The label stuck.

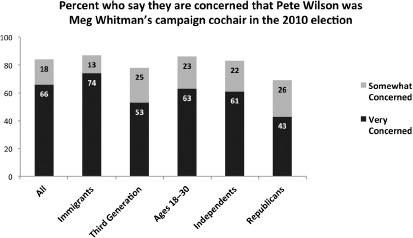

Third, any credibility that Whitman had on immigration was further eroded when she appointed Pete Wilson, the former Republican governor and architect of the Prop 187 anti-immigration initiative, as a co-chair of her election campaign. Though this came sixteen years after the passage of the dreaded initiative—one credited with reshaping California politics4—a huge share of Latino voters in the state held strongly negative associations with Pete Wilson. Figure 7.5 illustrates attitudes about Wilson among Latino voters. Even among eighteen- to thirty-year-old voters, who were between the ages of two and fourteen when Prop 187 was passed, 86% were somewhat or very concerned that Whitman had tapped Wilson.

Finally, the salience of the immigration issue was raised, not lowered, over the course of the campaign by the revelation that Whitman had an undocumented person performing domestic labor in her home. Exacerbating the situation, Whitman had fired this person in June 2009, on the eve of her campaign for governor. In the minds of the voters, Whitman was wrong twice. Her credibility on immigration was undermined by her alleged knowledge of having an undocumented worker in her employ. And her treatment of that employee was similarly found to be both hard-hearted and self-serving.

FIGURE 7.5 California Latino Voters’ Perceptions of Former Governor Pete Wilson, September–October 2010

![]()

![]()

The Colorado Senate Race Like the gubernatorial race, the Colorado Senate race featured at least one candidate identified with the ideological, or “Tea Party,” wing of the Republican Party. Ken Buck, the GOP nominee in Colorado, held forcefully articulated views on immigration and immigrants. He made his name in state politics as the district attorney of Weld County, a role in which he masterminded what was then the largest immigration raid in US history—a 2006 raid of a beef processing plant in Greeley. A profile in The Nation described his interest in the immigration issue as “obsessed.”5 During the course of the campaign, he accused incumbent senator Michael Bennet of favoring “amnesty.”

But Colorado’s electorate was 17% Latino in 2010 (and almost 20% today). Using our 2010 election eve poll, Latino Decisions estimated that Senator Bennet received 81% of the Latino vote, meaning that Latinos contributed a net 6.2% to Bennet’s total on election day. Since the statewide margin was only 1.7% of the vote, a more even distribution of Latino votes would have meant an easy win for Buck. Senator Bennet owes his seat to Latino voters.

The Nevada Senate Race Harry Reid is pivotal to our story in two very important ways. First, as the Senate majority leader, it was he who brought the DREAM Act to a vote in September 2010. Second, as an incumbent seeking reelection, he faced one of the most explicitly racialized campaigns of the year, run by his challenger, Sharron Angle.

Angle, a former Republican member of the state legislature, ran an insurgent campaign against the presumed nominee, Sue Lowden, a former local TV news celebrity, and two others. Angle defeated Lowden by around fourteen percentage points, in some measure because Democrats and their allies had targeted Lowden (who they perceived as the bigger threat) with ads during the primary campaign, and in part as a consequence of the Tea Party emergence in 2010.

Angle is, to put it mildly, erratic in public. She’s prone to gaffes and appears to have fringe beliefs regarding 9/11, the Department of Education, Muslims, the United Nations, and other bêtes noires. But none of her views attracted as much attention as her views on immigration, which became the centerpiece of her advertising campaign.

In a widely decried ad—a version of which other GOP nominees ran in other states—Senator Reid’s support for the inclusion of undocumented persons in several federal benefits programs was illustrated with images of apparent gang members who Reid would help go to college, frightened and frustrated (white) Americans, and a classroom full of (white) American children who would apparently be prevented from speaking English if Reid was reelected.

To be sure, Reid was aided by substantial voter registration efforts in Nevada between the 2008 and 2010 elections by organizations like Mi Familia Vota and the Hispanic Institute, among others. But there is no question that Angle’s specifically racial ads had a significant effect on Latino mobilization and vote choice.

Almost every major poll predicted an Angle victory. But on election day, Reid defeated Angle by almost six percentage points. A Latino Decisions election eve poll estimated that 90% of Latino voters chose Harry Reid (a number we have since validated with precinct-level analysis). Without Latinos, or with an even distribution of Latino votes, Reid would have lost and Angle would have won.

FIGURE 7.6 Latino Voter Attitudes on the Importance of the Immigration Issue to their Vote Choices, Election Eve 2010

![]()

![]()

Although overall the 2010 midterms were a pretty thorough defeat for Democrats, in numerous elections in 2010, and particularly in elections in the West, Latinos showed that they are a critical element in the Democratic coalition—without them, Democrats lose elections. Immigration was front and center in the minds of the voters we interviewed. As we report in Figure 7.6, 60% of Latino voters said that immigration was “very” important to their choice to vote and their choice of candidate, while another 23% said that it was “somewhat” important. Immigration politics affects the vote choices and mobilization of Latinos across national-origin groups and generations, and it has become even more important to Latinos as some states have tried to regulate immigration in harsh and racially suspect ways.