LATINO ENVIRONMENTAL ATTITUDES

With Adrian Pantoja

In 2010 Vista Valley Services submitted a proposal to the Pomona City Council in California to build a solid-waste transfer station in the city’s designated industrial zone.* If approved, the proposed waste transfer station would include a 55,000-square-foot building, sitting on ten to thirteen acres of land, and handle about 1,500 tons of trash per day. Open twenty-four hours a day, the site will process the contents of an estimated 600 garbage trucks daily. Advocates for the waste transfer station claim that it will create fifty permanent, well-paying jobs for a city that has endured decades of economic decline. Opponents, most of whom are Latino, claim that this proposal is the latest manifestation of environmental racism, since over 70% of the city’s residents are Latino and the proposed site is within a one-mile radius of nine schools, all of which are majority-Latino.

The Pomona case is not an isolated event. Latinos have mobilized elsewhere to protect their communities from environmental damages. In 1991 grassroots organizations and national environmental groups stopped the building of a hazardous-waste incinerator in Kettleman City, California, a predominantly Latino town. In the 1980s, the “Mothers of East Los Angeles,” a group of Latina churchwomen, prevented the building of an incinerator in the city of Vernon and later a hazardous-waste treatment plant in the city of Huntington Park. Both Vernon and Huntington Park are largely immigrant Latino cities. Indeed, environmental activism among Latinos can be traced back to the mid-1960s, when opposition to pesticides and other environmental toxins factored prominently in the union organizing of Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Workers.

Of course, protests and activism around environmental matters are frequently carried out by a small group of committed individuals who are willing to spend the time and energy to protect the wider community. Absent in these examples are data documenting the feelings and beliefs of Latinos more generally. In other words, despite these examples and the prevalence of environmental hazards in Latino communities, only a handful of studies have systematically analyzed the environmental attitudes of Latinos.1 As Latinos gain a meaningful voice in government, they will be in a position to develop and influence public policies. Will environmental issues factor prominently in their policy agenda? How will environmental issues rank for Latinos relative to other issues?

DO LATINOS CARE ABOUT THE ENVIRONMENT?

The dearth of research investigating Latino environmental attitudes suggests that scholars assume that Latinos have other policy priorities, like immigration or education. Indeed, there is a general assumption that concern for the environment is largely a white issue. Early research comparing white and African American environmental attitudes seems to confirm this assumption.2 The theoretical framework underlying these initial studies draws on Maslow’s “hierarchy of needs” theory by essentially arguing that poor and minority populations have more pressing issues like personal security, economic needs, affordable housing, better schools, and affordable day care services and that, compared to these pressing needs, environmental matters are secondary or insignificant.3 Whites and affluent individuals in the United States and other Western industrialized countries, so the argument goes, have had their basic material needs met and therefore have the time and money to concern themselves with other, more distant matters like environmental conservation.

A counter-hypothesis, the “environmental deprivation” theory, argues that the poor and minorities display greater concern relative to whites because they are directly affected by environmental problems.4 Direct experience with environmental issues, such as high levels of air pollution, toxic waste, and contaminated water, makes them as important as social issues in these communities, and this direct exposure to environmental problems, the theory argues, leads to more pro-environment attitudes in these communities compared to the attitudes of people with more limited experience or exposure to these problems. Thus, since Latinos and other minorities suffer disproportionate rates of environmentally related morbidity and mortality, these groups are more likely to display awareness of and concern for the environment.

Whether Latinos and other minorities display higher or lower levels of pro-environment attitudes largely depends on the environmental issues being studied. For example, Latinos are likely to display less concern over offshore oil drilling than whites because few Latinos live near coastal areas, especially in California. When it comes to air pollution or the storage of toxic waste, however, Latinos display higher levels of concern because these environmental issues have a disproportionate impact on them.5

Using polling data on Latino environmental attitudes from the California field polls from 1980 to 2000, Matthew Whittaker, Gary Segura, and Shaun Bowler laid out six environmental policy issues:

1. Air and water pollution

2. Protecting the state’s environment

3. Toxic waste

4. Spending on the environment

5. Self-identifying as an environmentalist

6. Offshore drilling6

On the first three issues, Latinos displayed higher levels of concern than whites and African Americans, thus lending support to the environmental deprivation hypothesis. On the last three issues, however, Latinos were no more concerned than whites, and in one instance, offshore drilling, they were less concerned than whites, demonstrating that proximity to an environmental issue influences attitudes. Other studies have produced mixed results when comparing Latinos’ environmental attitudes with those of whites. For example, research by Michael Greenberg and by Cassandra Johnson, J. M. Bowker, and Ken Cordell finds that the environmental attitudes of native-born Latinos closely resemble those of whites, while Bryan Williams and Yvette Florez find that perceptions of environmental inequities are higher among Mexican Americans.7

Yes, We Care

There is evidence that on some environmental issues Latinos display higher levels of concern than whites.8 Latinos are particularly concerned about environmental issues that pose an immediate health threat to their families and communities—specifically, brownfields and toxic sites, particulate air pollution from diesel exhaust near industrial zones, and the like. This makes sense in light of other research showing that Latinos react to threatening political issues by taking an interest and participating in politics at higher rates than whites do.9 Nonetheless, a deficiency of the existing scholarship is that studies of Latino environmental attitudes are limited to studies in a few geographic areas conducted over a decade ago.

Despite their limitations, these studies are significant in that they supplement anecdotal evidence with empirical evidence that the Latinos in their samples displayed pro-environment beliefs. Nonetheless, it’s important to go beyond these state-specific investigations and offer a broader and more contemporary view of Latino environmental attitudes. This study fills this gap by drawing on data from focus groups and a unique national survey of Latino environmental attitudes carried out by Latino Decisions on behalf of the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC).10

Prior to the survey, researchers at Latino Decisions conducted focus groups in Chicago, Illinois; Arlington, Virginia; and Charlotte, North Carolina. Contrary to the stereotype that Latinos are unconcerned about environmental issues, we found that all of the participants were engaged by the topic we presented and quick to offer opinions. We opened the discussion with the broad question: “There are lots of environmental issues facing the country and world. Of all of the environmental issues out there, which are you most concerned about?” Much of the discussion centered on global warming, climate change, and air pollution. The comment of one female respondent from Charlotte is representative: “I would say it’s air pollution, air pollution, that worries me the most . . . the kind that comes from factories, you know, the big factories. It bothers me when I’m driving around and I see the smog damaging the air that you breathe every day. That bothers me a lot.”

Not only were participants engaged by the topic, but many were strongly supportive of government legislation and policies designed to reduce air pollution and combat climate change. Even when weighing the economic consequences of such programs, Latinos did not back away from protecting the environment. One of the reasons participants gave for favoring environmental action was that they were deeply concerned about the well-being of their children and future generations. And an unanticipated finding from the focus groups was that respondents often discussed environmental issues in their home country and displayed a great deal of concern for their relatives back there. For instance, a female respondent in Arlington said: “Not in my immediate community here but back in my country, I know that the drought season is worse. That the people in the two previous years are dealing more with the lack of water. And the poverty in several areas is increasing because of . . . the crops get withered either because there is lack of water or excess water during the times when it wasn’t supposed to be raining.”

The focus groups were instrumental in helping us design the survey, which would include many questions on themes drawn from the groups. We included a wide range of policy questions in addition to those designed to provide a social, political, and demographic profile of the respondents.

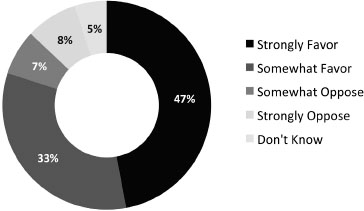

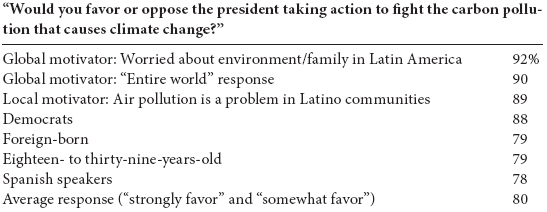

The survey results revealed that Latinos are very concerned about climate change and air pollution and support government action to remedy these problems. In the survey, Latinos were asked if they favored or opposed the president taking action to fight the carbon pollution that causes climate change. A robust 80% stated that they “somewhat favored” or “strongly favored” presidential action (see Figure 12.1). In a related question, 78% of Latinos agreed (“somewhat” or “strongly”) with the more general statement, “We need strong government actions to limit climate change.” In fact, the survey shows, environmental issues come in second only to immigration reform as a top policy issue for Latinos.

FIGURE 12.1 Support for the President Taking Action to Fight the Carbon Pollution that Causes Climate Change, 2014

![]()

![]()

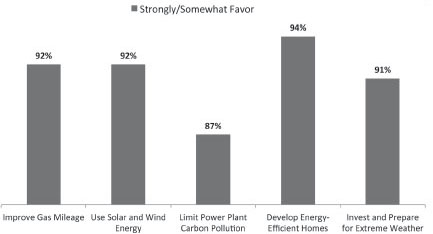

Respondents were also asked to state their level of support for five policy ideas proposed by the scientific community for combating climate change:

1. Requiring better gas mileage for automobiles

2. Increasing the use of renewable energy, such as solar and wind

3. Setting limits on the amount of carbon pollution that power plants can discharge into the air

4. Building homes and buildings that are more efficient and use less energy

5. Investing and preparing our communities for future weather events like storms, floods, or hurricanes

Over 90% of Latinos favored (“strongly” or “somewhat”) four of these five proposals (Figure 12.2). The only policy idea that fell below 90% was setting limits on the amount of carbon pollution that power plants discharge.

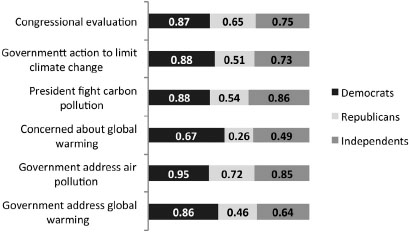

The high levels of pro-environment beliefs were found across most segments of the Latino electorate. We cross-tabulated the responses by a variety of sociodemographic, attitudinal, and political characteristics and found few differences across age groups, nativity, language use, gender, income, education, and other characteristics. The one factor associated with significant differences in attitudes was partisanship; there were significant differences between Latinos who self-identified as Democrats, Republicans, or independents. Of the three groups, Democrats displayed the highest level of pro-environment attitudes, while Republicans displayed the lowest. Independents fell between these two extremes. Figure 12.3 illustrates the partisan divided across the following six questions:

FIGURE 12.2 Latinos’ Attitudes on Scientists’ Proposals for Fighting Climate Change, 2014

![]()

1. “If your member of Congress issued a statement giving strong support to limit the pollution that causes climate change, would that make you feel more favorable or less favorable towards them?” [“Much more likely” and “somewhat more likely” responses are reported in Figure 12.3.]

2. “We need strong government actions to limit climate change.” [“Strongly agree” and “somewhat agree” responses are reported in Figure 12.3.]

FIGURE 12.3 A Partisan Divide among Latino Voters Who Self-Identify as Republican, Democrat, or Independent

![]()

![]()

3. “Would you favor or oppose the president taking action to fight the carbon pollution that causes climate change?” [“Strongly favor” and “somewhat favor” responses are reported in Figure 12.3.]

4. “Most scientists say that the Earth is getting warmer and it is human activity that is causing it. They call it ‘global warming’ or ‘climate change.’ How concerned are you about global warming or climate change?” [“Extremely concerned” and “very concerned” responses are reported in Figure 12.3.]

5. “Now just thinking about the environment. How important do you think it is for our government to address each of the following issues: air pollution?” [“Extremely important” and “very important” responses are reported in Figure 12.3.]

6. “Now just thinking about the environment. How important do you think it is for our government to address each of the following issues: global warming and climate change?” [“Extremely important” and “very important” responses are reported in Figure 12.3.]

There was a twenty-two-point gap between Democrats and Republicans when it came to supporting a member of Congress for issuing a statement about limiting pollution. There was a thirty-seven-point gap between Democrats and Republicans on government action to limit climate change. Supporting presidential action to fight carbon pollution showed a thirty-four-point gap between Democrats and Republicans. By far the largest gap (forty-one points) was found on the question tapping concerns over global warming. The second-largest gap (forty points) emerged from the question on whether the government should address global warming. Finally, there was a twenty-three-point gap on the question of whether government should address air pollution.

Although the partisan gap is significant, it is politically inconsequential at this point in time given that Latinos overwhelmingly identify as and vote Democratic. Should the Republican Party make significant inroads with the Latino electorate, however, it is likely that their policy priorities will shift. One area that is likely to experience the greatest shift is on policies pertaining to the environment.

WHY DO LATINOS HAVE PRO-ENVIRONMENT BELIEFS?

Having shown that Latinos display high levels of support for environmental policies, we need to explore the factors underlying their concerns. Clearly, there is a significant partisan gap, but are there other factors that may be predictive of Latino environmental beliefs?

If proximity to environmental issues causes Latinos to display high levels of concern, we should see strong support for policies related to air pollution, since this is one of the greatest threats to Latino communities.11 According to a recent study by the Natural Resources Defense Council, “Nearly one out of every two Latinos lives in the most ozone-polluted cities in the country.” Living in cities with high levels of air pollution has a direct effect on Latinos’ health outcomes. According to the NRDC report, “Latinos are three times more likely to die of asthma than other racial or ethnic groups.”12 To capture Latino concerns about environmental issues on a local level, the survey asked: “Thinking about the city where you live, would you say that air pollution is a major problem, somewhat of a problem, or not a problem in your city?” Sixty-nine percent of Latinos said that air pollution was a problem (“a major problem” or “somewhat of a problem”) in their city. Latinos who see air pollution as a problem in their city display higher levels of pro-environment evaluations relative to Latinos who say air pollution is not a problem. This local environmental concern is a “local motivator.”

In our survey, contrary to the findings by Greenberg and by Johnson, Bowker, and Cordell that concern is highest among acculturated English-speaking Latinos, Spanish speakers displayed higher levels of pro-environment attitudes.13 This is a significant finding considering that over 40% of Latinos are foreign-born—which brings us to our second set of predictors: transnational ties and global orientations.

Latinos are distinct from Anglo Americans in that large numbers have established transnational ties with their home country. Transnational ties are captured with the following question: “Thinking about any family who is living in [country of origin]. How worried are you about environmental problems in their communities?” In the survey, 63% of respondents said that they were “very worried” or “somewhat worried.” Finally, the ties that Latinos maintain with their home countries have led to the development of a global orientation. Respondents were asked if they thought about the moral or ethical reasons why the earth should be protected in terms of themselves, their family, their community, their country, or the entire world. Majorities said “the entire world” needs to be protected.

Latinos who have transnational ties and a global orientation display higher levels of pro-environment attitudes than other Latinos. These two additional factors can be characterized as “global motivators.”

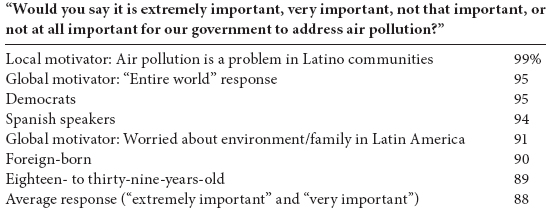

To assess the impact of local and global motivators on Latino environmental attitudes, these motivators and other demographic factors were cross-tabulated with the following three policy questions:

1. “Would you say it is extremely important, very important, not that important, or not at all important for our government to address air pollution?”

2. “Would you favor or oppose the president taking action to fight the carbon pollution that causes climate change?”

3. “If your member of Congress issued a statement giving strong support to limit the pollution that causes climate change, would that make you feel more favorable or less favorable towards them?”

How did local and global motivators stack up as factors eliciting environmental support from Latinos? If we look at the average response across the three questions, we see that Latinos were strongly supportive of the government combating air pollution (88%) as well as presidential (80%) and congressional (78%) action on climate change. Overall, the respondents who were captured by these seven demographic and attitudinal characteristics (as seen in Tables 12.1, 12.2, and 12.3) scored well above the average response rate. Democrats in particular displayed high levels of pro-environment attitudes. However, the global and local motivators outperform the four demographic factors. For example, in Table 12.1, 99% of respondents who said that air pollution is a problem (“a major problem” or “somewhat of a problem”) in their city also said that it is important (“extremely important” or “very important”) for the government to address air pollution. On this issue, the local motivator seems to have been underlying Latino support for government action on air pollution. Table 12.1 also shows that global motivators significantly drive Latino attitudes. On the two other questions (Tables 12.2 and 12.3), respondents with global and local motivators were the most supportive of presidential and congressional action. This is not to downplay the significance of the demographic factors, but it does illustrate that they are not as significant as the local and global motivators.

Scholars have largely overlooked the impact of transnational networks in shaping environmental attitudes, primarily because public opinion studies on the environment have explored Anglo American attitudes to a much greater extent, and this group, being so far removed from the immigrant experience, has few ties abroad, if any. Among Latinos, however, transnational networks have a significant impact in shaping environmental attitudes.

![]()

TABLE 12.1 The Importance of Air Pollution to Latinos

![]()

TABLE 12.2 Support among Latinos for Action to Fight Climate Change

![]()

TABLE 12.3 Latinos’ Approval of Members of Congress Who Speak Out on Carbon Limits

![]()

Source for Tables 12.1–12.3: Latino Decisions Climate Change Survey, December 2013.

![]()

It is a false assumption that Latinos neglect environmental issues because they are preoccupied with other, more pressing issues, such as immigration reform. Many Latinos live in communities plagued by high levels of air pollution, toxic and industrial waste, and contaminated water. The adverse health consequences of living in such environmental hot spots are well documented.

Latinos of all sociodemographic groupings displayed pro-environment attitudes, but certain segments stood out as having higher levels of support for environmental issues. Specifically, pro-environment sentiment is higher among Democrats, younger Latinos (eighteen- to thirty-nine-year-olds), Spanish speakers, and the foreign-born. Still, local and global motivators were even more significant. Latinos who worried about the environment and their family in Latin America, who had a global orientation, and who were concerned about air pollution in their cities displayed the highest levels of pro-environment beliefs. These are not small segments of the Latino population: about two-thirds of our respondents could be classified as possessing local and global motivators.

This chapter began with the political battle over a solid-waste transfer station in Pomona, California. Whether the city council ultimately approves the building of this facility remains an open question at the time of this writing. Given the prevailing stereotypes about Latinos and their environmental attitudes, proponents of the waste transfer station may not have anticipated the fierce Latino opposition. Perhaps one reason why Pomona was selected for the facility rather than its wealthier neighbor Claremont was precisely because most of its residents are low-income immigrants. Claremont is a wealthy Anglo American city that prides itself on its environmental consciousness. Our survey shows, however, that Latinos also care deeply about the environment and have much to say about air pollution, climate change, and other environmental issues. Latinos are determined to take part in politics and engage in national debates on a wide range of issues. When it comes to protecting the environment, Latinos are eager to have their voices heard, even if some Americans seem unaware that Latinos have something to say at all.

![]()

*Adrian Pantoja is the lead coauthor of this chapter.