ONEIDA

Kingdom Come

The sin-system, the marriage-system, the work-system, and the death-system, are all one, and must be abolished together. Holiness, free love, association in labor, and immortality, constitute the chain of redemption, and must come together in their true order.

—JOHN HUMPHREY NOYES

Burned

On the evening of April 5, 1815, people on the Indonesian island of Sumatra heard the faint, rumbling sounds of a distant naval skirmish. To the east, on the island of Sulawesi, the noise was more distinct. British soldiers stationed there could make out the low, intermittent crack of cannon fire interspersed with the stuttering report of small arms. Assuming that a merchant ship was under attack by pirates, British officials dispatched the Benares, an armed cruiser operated by the East India Company, to find and engage the enemy.

For three days, the crew of the Benares sailed from harbor to harbor looking for the pirates. Failing to find any sign of a battle, they returned to port. Two days later, the clamor resumed, louder and more frequent. Within the heavy walls of the British fort, plates and cups rattled.

The next morning, the sky went black. “By noon complete darkness covered the face of the day,” wrote Thomas Stamford Raffles, captain of the Benares. “I never saw anything to equal it in the darkest night.”

There had not been any skirmish. The noise came from the island of Sumbawa, a full sixteen hundred miles from Sumatra, where Mount Tambora was erupting.*1 Despite the volcano’s remote location, more than ten thousand people were killed by its eruption and the tsunami it caused. Twenty-four cubic miles of debris were launched into the atmosphere, blotting out the sun for hundreds of miles. The cloud of sulfurous ash spread, dimming the sun over most of the Northern Hemisphere. Byron commemorated the cataclysm with the poem “Darkness” (1816): “I had a dream, which was not all a dream. / The bright sun was extinguish’d, and the stars / Did wander darkling in the eternal space, / Rayless, and pathless, and the icy earth / Swung blind and blackening in the moonless air; / Morn came and went—and came, and brought no day.”

In New England, where the founding Brook Farmers were still in short pants, a mysterious red haze hung in the air all summer. The next year, 1816, was freezing. The press called it “Eighteen Hundred and Froze to Death” and “the Year Without Summer.” In early June, six inches of snow fell on northern New England, killing tender young crops. Farmers worked through the night to replant. When more snow fell in July and August, the second planting was wiped out. In some parts of northern New England, there were twelve consecutive months of ice and snow. Freshly shorn sheep froze to death standing up in the fields.

In Europe, the cold weather caused food shortages, famines, and riots. In the United States, the farmers of New England’s hill-country villages were the hardest hit. Even without Tambora’s eruption, the first quarter of the nineteenth century was a trial for the region. In 1811, powerful floods washed away mills and drowned cattle. In 1812 and 1813, “spotted fever” (meningitis) felled 3 percent of Vermonters. In 1826, a plague of grasshoppers devoured harvests. During “the Year Without Summer,” when corn would not grow, some farmers starved. Countless others were ruined.

The victims of these disasters were the children of the Great Awakening—the descendants of the Puritans. They saw the hand of God in everything. To them, this punishing concatenation of natural disasters seemed like divine judgment. Worn down, farmers from the scrabbly, overfarmed uplands of western New England pulled up stakes. Like dust bowl Okies pouring into California’s verdant Central Valley, an exodus of poor Yankees moved west across the Hudson River, toward the deep, alluvial topsoil of New York’s broad, green western valleys. Entire New England villages were packed up, carried west, and reassembled in western New York. Beset by famine, floods, locusts, and pestilence, these God-fearing refugees arrived in their promised land with an apocalyptic cast of mind.

At first, western New York did seem like a land of honey and milk. The Erie Canal, begun in 1817 and completed in October 1825, painted a wide stripe of prosperity all the way across the state. By linking the Great Lakes to the Hudson, the canal connected the frontier to the port of New York City and the world. On the morning of its opening, cannons were arrayed at intervals along the canal’s route and down the Hudson to New York City. Starting in the west, a triumphant booming signal dominoed its way from Lake Erie to the Atlantic coast and back in three hours and twenty minutes. In the decade before the telegraph, it was a thrilling conquest over time and space.

The canal shortened the time it took to cross New York from a matter of weeks to a matter of days. The cost of transporting freight from the frontier to the coast was cut dramatically. The man-made river carried more than twice as much cargo as the Mississippi. Barges laden with Manchester calico, Chinese china, machine parts, and European immigrants traveled west, passing eastbound boats riding low with lumber, salt, and flour.

Although the canal transformed the national economy, its strongest impact was on the section of New York through which it passed. Along with the jobs created by the work of digging and paving the waterway, countless factories sprang up along the canal’s route. Towns such as Utica, Buffalo, and Rochester boomed.*2

The social and economic changes taking place along the canal route were an amped-up version of what was happening throughout the Republic. The Yankees in western New York came from small communities of subsistence agriculture. In their old life, the life of their parents and grandparents, family members worked side by side on a single plot of land. They raised a few animals, worked a patch of corn, spun their own woolens, milled their own grain, and made their own shoes and soap. There was little distinction between working hours and nonworking hours. Folding money, when they had any, was for a new kettle, a bottle of patent medicine, a Bible. Life was almost entirely dependent on one’s land, labor, and the weather. Ideas, other than those about sin and rain, were scarce.

Things were different in the canal zone. Work and life began to separate. Men went to earn wages on large farms or in small factories. Women stayed home, raising children, keeping house, and taking in piecework. Grown sons (and to a lesser extent grown daughters) traveled away from home to find work. The entire country was shifting rapidly from a rural agricultural economy to an urban industrial economy. In western New York, that transformation seemed to be happening overnight.

The manufactories that sprang up along the canal required capital to buy large machines. Cash-cropping farmers needed loans to buy huge tracts of land. Investors in lower Manhattan paid hard cash for wheat that had not even germinated. Working people in remote places were suddenly entangled in financial markets as far off as London. The canal showed the world a man-made river. Now something called the national economy entered the lives of ordinary people like a man-made version of the weather: a vast, unpredictable force with limitless power over daily life.

The Panic of 1837 derailed western and central New York’s vigorous economy. When the inflated price for commodities plummeted, the region slipped into a depression. The sudden downturn was as mysterious as the red haze caused by Tambora’s eruption. As the historian Michael Barkun wrote, this rapid transition from natural disaster to man-made calamity gave the citizens of western New York “a special receptivity to millenarian and utopian appeals.” The new world demanded new ways of living.

In a place increasingly in the thrall of money and material progress, an alternate set of aspirations blossomed. During the late 1820s and early 1830s, hundreds of thousands of Americans converted to new evangelical denominations in a nationwide paroxysm of faith that came to be known as the Second Great Awakening. The excitement that had carried the Shaker gospel over the Alleghenies at the turn of the century had come east.*3 And once again, talk of the millennium was front and center.

Lay preachers saw “signs of the times” everywhere. They parsed each weird line of that ancient monster parade known as the book of Revelation and watched for clues in the weather, the Vatican, the Congress, even in the distant power struggles of the Ottoman Empire. This sort of horizon gazing was especially common in the newly settled counties of western New York, a place where ideas moved fast and the world seemed to be transforming on a daily basis. The historian Whitney Cross called the canal a “psychic highway.”

The new religious excitement spilled out of traditional churches, spawning small denominations by the dozen. Circuit-riding evangelists blanketed upper New York. At rollicking tent meetings, they summoned souls to Christ, telling Americans that salvation was in their hands. Western New York was so crowded with revivals that Charles Grandison Finney, the signal voice of the Second Awakening, dubbed it “the Burned-over District”—a place where the smell of brimstone seemed to hang in the air and scant fuel (sinners) remained to feed the revivalist blaze.*4 In 1830 alone, more than one hundred thousand western and central New Yorkers were “born again” into the new millenarian churches.

Spiritual and social innovation were fully intertwined. The future-facing citizens of the Burned-over District were at the vanguard of almost every nineteenth-century reform movement. The region was ground zero for abolitionism, feminism, the temperance movement, anti-Masonry, Shakerism, and a wide array of utopian communalist schemes. During the 1840s, the region was home to the country’s highest concentration of Fourierist phalanxes. At least ten were planned; seven were actually built.

Mormon prophet Joseph Smith, whose family moved from Vermont to Ontario County during “the Year Without Summer” as part of the Yankee diaspora, became the most successful of the region’s many revelators. He described the district as a place of “unusual excitement on the subject of religion…an extraordinary scene…a strife of words and a contest about opinions.”

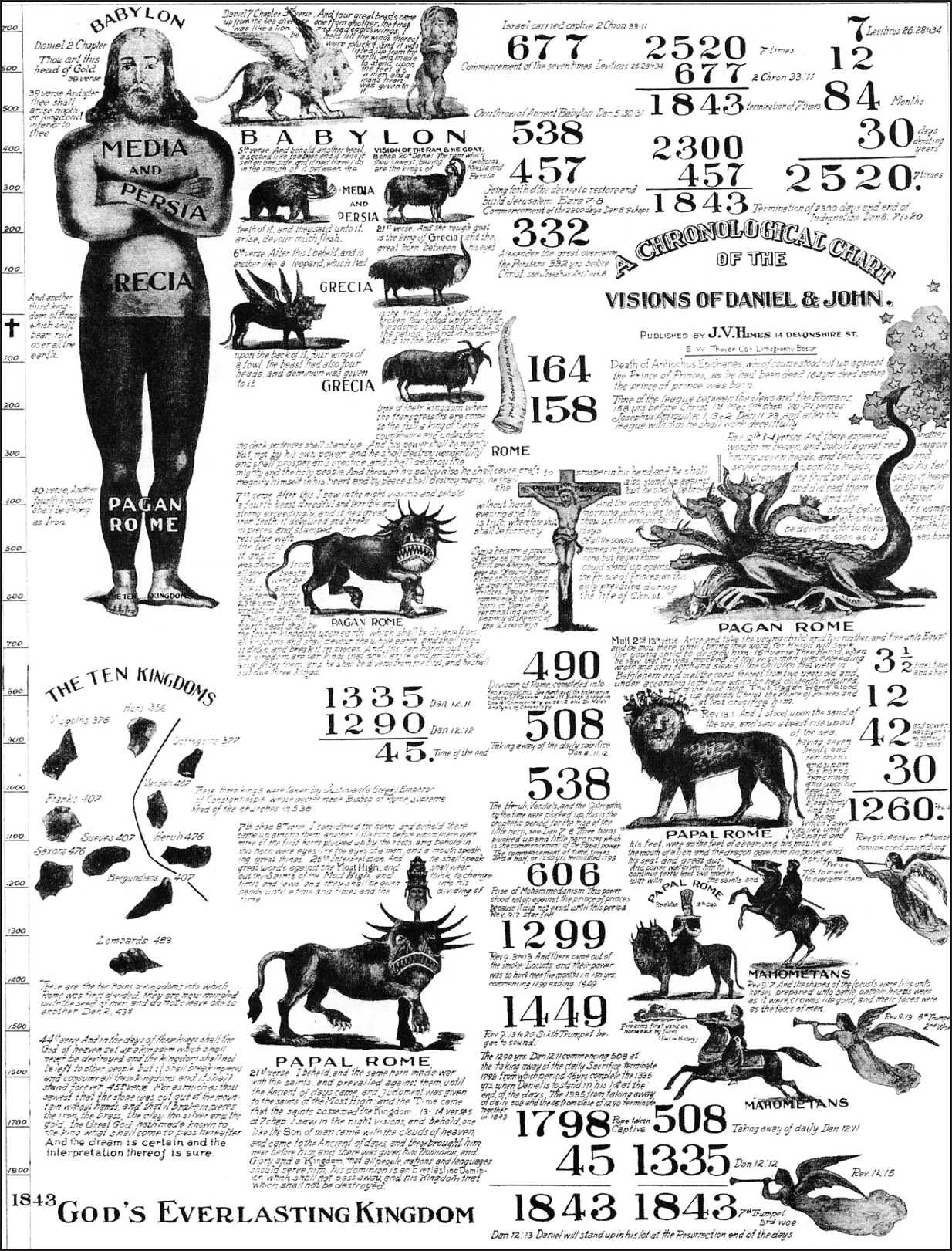

In 1843, on the eve of Fourierism’s tidal surge into western New York, people in the region were enthralled by the apocalyptic calculations of an unassuming local farmer named William Miller. Miller, a veteran of the War of 1812, had no formal theological training, but in 1831 he read the book of Daniel and, using a variety of ancient calendars, calculated that Christ was scheduled to return to the earth sometime between March 1843 and March 1844.*5 Miller’s announcement of the imminent Second Advent struck a chord in a time and place where many people expected the end of history to arrive at any minute. To spread the word of the coming rapture, the “Millerites” held large revivals and printed illustrated posters outlining their apocalyptic math.

When Jesus failed to show during his allotted time, one of Miller’s followers recalculated using a different, older Hebraic calendar, granting the Son of Man an extension until October 22, 1844. On that day, as many as fifty thousand Americans gathered outside to be beamed heavenward. Many of them had sold their homes and left their fall crops to rot in the field. Some had sent money to the federal government, paying off previously dodged taxes. When nothing happened, the press gleefully chronicled the “Great Disappointment,” reporting erroneously that the believers had donned white “ascension robes” to meet their Maker.

Primed for heaven, thousands of Millerites were set adrift. One group sent word to New Lebanon requesting a Shaker mission. They formed a substantial harvest for the western New York villages. Others filed into the phalanxes that were just then springing up around Rochester. A few started their own small communes. The largest and most lasting spin-off of Miller’s movement was the Seventh-day Adventist Church, whose members still claim that October 1844 was a pivotal moment in the unfolding saga of the end times.

A widely distributed poster depicting William Miller’s calculations concerning the end of days.

Future Perfect

Three years after the Great Disappointment, a fresh millenarian excitement arrived in the heart of the Burned-over District. At the very center of New York State, twelve miles south of the Erie Canal, John Humphrey Noyes, a man whose thinking about the end of history developed partly in opposition to Millerism, established the Oneida Community, the most remarkable utopian experiment in American history. At the community’s peak, three hundred Oneida “Perfectionists” lived an intensely intimate, intellectual existence in a rambling, Italianate mansion. They saw their community as an earthly branch of the Kingdom of Heaven, a sort of portal through which the millennium would come to earth. Under the influence of their utopian forebears, the Perfectionists renounced private property, raised their children collectively, embraced gender equality, perfected a novel form of birth control, experimented with every health fad of their day, pursued rigorous self-improvement, practiced a complex system of free love, and initiated an unprecedented experiment in eugenics.

Even more than Robert Owen’s New Harmony or Étienne Cabet’s Icaria, Oneida is the story of one man’s evolving vision of the perfect society. John Humphrey Noyes was born in Vermont in 1811. His father’s side of the family had been in New England since 1634, when they made the crossing from England. John Noyes, Sr., studied and then taught at Dartmouth before moving to Brattleboro. There, he married Polly Hayes, the tall, red-haired daughter of a tavern keeper from a prominent Vermont family. When their neighbors began migrating west across the Hudson, the prosperous Noyes clan stayed in Vermont, settling in the Green Mountain village of Putney. John Sr. was elected to Congress and, in 1877, while Polly Hayes’s son was running his radical experiment in upstate New York, her nephew Rutherford moved into the White House.

Much of the energy of the Second Great Awakening came from women. In many of the new evangelical churches, they outnumbered men two to one. Polly Noyes was among them. In 1831, she dragged her skeptical eldest son to a four-day revival in Putney. John Jr. was twenty, a gangly, gray-eyed, ginger-haired young man. Fresh from Dartmouth, he was apprenticing at the law firm of his brother-in-law. With a head full of Byron, common law, and intellectual swagger, he went to the revival for the same reason that many people go to church—to please his mother. He wore bell-bottom pantaloons, fancy square-toed boots, and a fashionable pyramid-shaped hat.

For two days, Noyes regarded the hysterics around him with smug undergraduate detachment. On the third day, a strange calm came over him. That night he couldn’t sleep. Soaked with sweat, he lit a lamp and reached for the Bible. The familiar sentences of the New Testament seemed to glow on the page, lambent with urgency. On the fourth and final day of the Putney revival, John Humphrey Noyes pledged his life to the Word. “Hitherto, the world,” he wrote in his diary, “henceforth, God!”

His instincts were still academic. His first move was to take up Hebrew grammar. Within a month he was enrolled at the prestigious Andover Theological Seminary. It was a bad fit. With the restless zeal of a fresh-saved convert, Noyes disdained Andover’s staid, orthodox Congregationalism and the faculty’s attachment to Calvinist dogma.

Calvinism was the shipboard religion on the Mayflower. It was the founding American faith. Two of its central pillars are the conviction that humankind is irrevocably tainted by sin and that salvation and damnation are fixed, predestined. During the American expansion into the West, the belief that any freeborn (white, male) American could forge his own destiny was rapidly becoming the central myth of the Republic. This sense of possibility was at odds with the deterministic Calvinist account of salvation.

The revivalists of the Second Great Awakening offered a message that was better suited to the willful American citizenry. The whole purpose of a revival is to save unsaved souls. It is logically incompatible with the dogma of predestination. Under the new teaching, American sinners no longer dangled helpless above the fiery pit. The levers of salvation were in their hands.

Noyes was an enthusiastic exegete, but he loathed the detached “professional” spirit of Andover’s young churchmen in training. While his peers quibbled over hermeneutic minutiae, he buzzed with the kinetic intensity of the Putney revival. “My heart was fixed on the millennium,” he wrote, “and I resolved to live or die for it.”

After a year, he transferred to the comparatively progressive program at Yale, where the faculty were not so uniformly arrayed against the new Awakening. Noyes threw himself into his studies with renewed intensity. He also helped found an abolitionist group and preached in one of the city’s black “free churches.”

As he studied, Noyes found himself drawn to the ancient Christian doctrine of Perfectionism. In orthodox Christian theology, moral corruption is understood as the essential human condition. No human has been “perfect” (without sin) since Adam and Eve ate from the Tree of Knowledge. Perfectionists, by contrast, believe that a living Christian can be wholly freed from sin in this life and thus significantly closer to God. Some Perfectionists go so far as to claim that being a Christian requires total salvation from sin. The debate is as old as scripture. Matthew (5:48) says: “Be ye perfect.” John (1:8) says: “If we claim to be without sin…the truth is not in us.”*6 For a Perfectionist, being saved is to undergo a distinct transformation in the eyes of God. Some Perfectionists believe that this transformation exempts the perfected from the moral regulations that govern the unredeemed. Within the crowded spiritual marketplace of the Second Great Awakening, several strains of Perfectionism had begun to gather converts. The various groups were identified by their headquarters. There was “New Haven Perfectionism,” “Oberlin Perfectionism” (a less extreme position associated with Charles Grandison Finney), “New York Perfectionism,” and, eventually, “Oneida Perfectionism.”

This rise in Perfectionist theology paralleled a broader intellectual reorientation. Beyond the canvas big tops of the revivalists, a secular interest in social and individual “perfection” flourished.*7 Secular perfectionism, which provides the groundwork for utopianism, is the belief that progress—in matters scientific, artistic, moral, economic, medical, social—has no upper limit and that the world is approaching some ideal state.*8 It is impossible to fully unbraid the sacred and the secular threads of American perfectionism. They inform each other and stem from the same general sense about how the world works. Within the person of John Humphrey Noyes, they were wholly inseparable.

All of the nineteenth-century communal utopians spoke in the language of perfectionism. For the Shakers, perfection was a matter of melding individuals into a unified “body of believers” and keeping the imperfections of the World out. Their fastidious stone walls were a rampart against the fleshpots of Babylon. Robert Owen claimed that his hyperrational scheme was a mechanism of “endless progressive improvement, physical, intellectual, and moral, and of happiness, without the possibility of retrogression or assignable limit.” Fourier wrote that under his scheme, humans “will be elevated to perfection of body and mind.” Cabet felt much the same. “Man,” he wrote, “is evidently perfectible through experience and education.”

While most religious Perfectionists spoke of man’s perfectibility as a private spiritual enterprise, the communal utopians regarded perfection, including perfection of the soul, as an inherently collective project. Fourier claimed that the passions he identified will produce harmony when they are expressed in a crowd, whereas in solitude, human nature will “entice us only to evil.” A Shaker theologian wrote that the individual who seeks transcendence alone is like a foot separated from a body.

Sin No More

On a freezing Thursday evening in late February 1834, John Humphrey Noyes left the apartment he shared with his younger brother Horatio and hurried across New Haven toward the Orange Street Chapel, where he was scheduled to deliver a sermon. Noyes, then in his second year at Yale, was convinced that the Bible promised the possibility of total, sinless salvation. What he did not yet understand was how such salvation might be attained. Desperate for an epiphany on a par with his conversion in Putney, he had been up for nights poring over the Bible. Vanquishing sin could not simply be a matter of restraint or flawless behavior. Even sinful thoughts are an offense to God, and nobody can prevent the mind from wandering. He concluded that spiritual perfection must be more than rule following; it must be a mystical state, a purifying brush with the divine. Something that happens to you.

Stepping into the warmth of the chapel, Noyes removed his overcoat and then sat at a desk facing the congregation. The sparse assembly looked back in silence at their young volunteer minister. Reading calmly from prepared notes, Noyes gave a simple, perplexing sermon: “He that committeth sin is of the devil.” Having offered this single line from the book of John, Noyes then insisted on its literal meaning: If you sin at all, you are not a Christian. He stood, pulled on his coat, and walked back into the cold.

Lying in his bed that night, Noyes received the purification he had been craving. “Three times in quick succession a stream of eternal love gushed through my heart, and rolled back again to its source. Joy unspeakable and full of glory filled my soul. All fear and doubt and condemnation passed away. I knew that my heart was clean, and that the Father and the Son had come and made it their abode.” He was perfect. Like Ann Lee, who understood her jailhouse vision of Eden as the dawn of a new dispensation for all of humanity, Noyes interpreted his private epiphany as a cosmic event, a decisive step toward the millennium.*9

The next morning, one of Noyes’s classmates showed up at his apartment. He had heard the Orange Street sermon and wanted to know what Noyes meant by his claim that anyone who sins is of the devil. Humanity is defined by sin; God loves us despite our corruption. To preach that a Christian cannot sin would be to “unchurch” oneself. When Noyes simply repeated what he had said the night before, the frustrated seminarian put it squarely: “Don’t you commit sin?”

Knowing that his reply would “plunge [him] into the depths of contempt,” Noyes answered firmly: “No.”

Word of this heresy flew across the Yale campus. Incredulous young men packed the Noyes brothers’ rooms, quizzing John on his alleged sanctity. Even for the relatively forward-thinking faculty at Yale, this was too much. They revoked Noyes’s preaching license, expelled him, and suggested that he leave New Haven. He was unfazed. “I have taken away their license to sin and they go on sinning. So, they have taken away my license to preach, I shall keep on preaching.”

Kicked out of the Congregationalist Church and unmoored from institutional Christianity at the age of twenty-three, Noyes boarded a sloop for New York City. He took a room in a boardinghouse near Canal Street and, over the next three weeks, became completely unhinged. Tormented by visions of devils and angels, he did not eat or sleep. In a spell of paranoia, he wandered lower Manhattan by night. Test-driving his newfound sanctity, he drew close to sin, tasting his first hard liquor and preaching to stoned prostitutes in the narrow alleys of Five Points. One afternoon, he became certain that he was dying. He returned to the boardinghouse, lay down in his cot, and awaited the end. When the terror passed, Noyes felt reborn—purified. Satan had tested him and he had proven himself invincible. His spiritual perfection was intact. He later recalled that those three weeks alone in New York felt like three years.

At the time, there were several centers of Perfectionism in the Northeast. Noyes visited with most of the leading members of the movement, but he did not join forces with any of them. He believed that God had singled him out as a divine instrument. He could not countenance working beneath another preacher. For a time, he and an old friend printed a paper called The Perfectionist in New Haven, but the partnership didn’t last. Noyes drifted around the Northeast, preaching his new doctrine to anyone who would listen. He was often broke. At one point he walked for three days from New York City to New Haven without eating. His willowy frame grew emaciated.

Noyes was on the move for almost three years. It was a period, he later recalled, of “vagabond, incoherent service.” He was not a particularly passionate preacher. His genius was for conversation and the written word. Like Ann Lee, Noyes possessed a weird, otherworldly charisma that, among a certain kind of seeker, inspired complete devotion. As he traveled, he accumulated a modest flock.

Noyes returned to Putney to stay in 1836. His brother George and his sisters Harriet and Charlotte all came to regard John as their spiritual leader. Their mother held out for a while, but after months of daily sermonizing—“bullying,” she called it—Polly Noyes acknowledged her eldest son as her spiritual “father.” (The rest of the family never embraced John’s teachings, thus splitting the Noyes clan into two camps.)

When John Sr. died in 1841, Noyes and the three siblings he had converted pooled their inheritance and bought land adjoining the family farm. By then, some of Noyes’s other converts had gathered in Putney. Gradually, this small group of Perfectionists organized themselves into a loose community, which they called the Putney Bible School.

Noyes was torn between an urge to hit the road as an evangelist and the desire to build up a strong, stable congregation in Putney. This dilemma, between spreading the Word and living the Word, would never be fully resolved in him, but he settled on a compromise. He would stay with his followers in Putney and broadcast the Perfectionist gospel with a free newspaper, The Witness. Even more than most of the ink-stained reformers of his day, Noyes put great stock in the power of newsprint to change the world. The Perfectionists sometimes lived on thin potato soup, but they never skimped on ink or paper.

Noyes’s decision to remain in Putney was partly a reaction against revivalism, particularly the hyped-up mass hysteria of the Millerite movement, to which the Putney community lost a few members. Noyes wanted, he wrote, to put Perfectionism on a “permanent basis, not by preaching and stirring up excitement over a large field…but by devoting myself to the particular instruction of a few simple-minded, unpretending believers.”

By the winter of 1843, there were twenty-eight adults and nine children living on the Noyes family farm. Like the early Brook Farmers insisting that their plan had no connection to Fourierism, Noyes claimed that his ambitions were neither utopian nor socialistic. The Putney community was a prayer group and a publishing operation, not an “association.” That gradually changed. In 1846, as he later wrote, “the little church at Putney began cautiously to experiment in Communism.” The believers already studied together, farmed together, prayed together, worked together, and ate together. Now they began to hold all their property in common, too.

Like most communitarians of the nineteenth century, the Putney Perfectionists took inspiration from the social and economic arrangements of the primitive Christian Church as described in the book of Acts. Noyes believed that the first community of Jesus followers were theological Perfectionists but that their true, early Christianity had been lost at the close of the age of the apostles. Since that time, Christendom has been stuck in a long dark age that Noyes called “the Apostasy.” By imitating the spiritual communism practiced by the first Christians, Noyes intended to revive true Christianity, thus initiating the long forestalled promises of the millennium. As with all religious sects, it is impossible to draw a clear distinction between the Perfectionists’ spiritual inspirations and their workaday needs. Along with Noyes’s reading of Acts, the practical necessities of rural living probably helped spur the believers into communism.

Noyes’s defining quality was a total refusal to acknowledge any division between theory and practice. Every idea that popped into his head was immediately transmitted into experiment. He understood his own spiritual perfection as a sudden, mystical experience—a union with that which is metaphysically perfect (God). Although that experience freed him from the taint of original sin, it did not translate into worldly infallibility. Social perfection—the building up of the millennial kingdom—would not come like a flash. It would be a process, requiring hard thinking, trial and error, and a great deal of human creativity.

Like all utopians, Noyes had little regard for the way things are usually done. He overthrew long held customs with remarkable ease. When it occurred to him that the practice of eating three hot meals a day subjected women “almost universally to the worst of slavery,” he simply stopped it. The thirty-odd members of the Putney community ate one sit-down meal in the morning and then foraged for themselves from an open pantry “as appetite or fancy may suggest.” The door to the pantry was marked with a card bearing the motto “Health, Comfort, Economy, and Woman’s Rights.” Later, when the Perfectionists had more money, they went in the opposite direction, experimenting with Fourier’s eight-meal-a-day schedule.

It was not by coincidence that the Perfectionists began forming themselves into a commune just as American Fourierism reached its zenith. The Putney community was directly inspired by Brook Farm, which collapsed the same year the Perfectionists began formally organizing themselves as a community. Although Noyes had a revivalist’s distaste for the coolheaded abstractions of Unitarian theology, he regarded George Ripley as a moral and intellectual titan. To Noyes, the continuity between what he was doing in Vermont and what the Fourierists were doing elsewhere was self-evident. The community in Putney, he wrote, “drank copiously of the spirit of [Brook Farm’s] Harbinger and of the socialists.”

For their part, the leading Fourierists regarded the Perfectionists as sincere, if slightly addled, comrades. In the winter of 1846, two Brook Farmers visited the community in Putney to lecture on Fourierism. After returning home, they reported in The Harbinger that the Perfectionists were “well-meaning people, ardently longing for a divine order of society,” but that their fixation on spiritual matters kept them from appreciating “sufficiently the influence of social institutions.” Not surprisingly, the Brook Farmers suggested that the Putney communists would benefit from reading more Fourier.

In his own paper, Noyes responded to this assessment by saying that his community certainly admired Fourier, but only as one of several influences. “On many points [Fourier’s] philosophy well agrees with our principles,” he wrote. “But we can say nearly the same of the Shakers.” Noyes believed that Fourier’s philosophy—which, like most Americans, he received via Brisbane, Dana, Ripley, and Greeley—focused too much on social arrangements while neglecting the importance of the individual. He believed that “social perfection,” which for him was synonymous with the millennium, had to commence with the cultivation of the soul, not social structures. The Fourierists, he wrote, were proceeding backward—“trying to build a chimney by beginning at the top.” Noyes called his community a “spiritual phalanx.”

The Fourierists, Owenites, and Icarians all tapped into a pervasive belief that some sort of man-made golden age was about to commence. The Perfectionists, like the Shakers, combined this sort of general millenarian optimism with a specific story about the Second Advent and the prophesied reign of heaven on earth. Most American Christians were divided over whether Christ would return before or after the millennium.*10 Noyes offered a surprising third option: Christ had already returned and left again. Noyes believed that the Second Coming had been in AD 70, when Roman legions marched on Jerusalem to suppress a Jewish uprising and sacked the Second Temple. The notion that Christ would return just four decades after his death certainly fits with what he told his followers, at least according to the Gospels. “Verily I say unto you,” Jesus says to his brother and two other men in the Gospel of Matthew (16:28), “there be some standing here which shall not taste death till they see the Son of man coming in his Kingdom.”

For Noyes, the fact that Christ had already made his promised return did not mean that the “resurrection state” of the millennium had already begun, only that it was now possible for individuals to attain spiritual perfection and begin the work of perfecting society. The Savior had done His part of the saving. It is up to humanity to finish the job.

There is an inherent conceptual tension between Christianity and utopianism. In one sense, the dream of a man-made utopia is a Promethean blasphemy. How can anyone presume to devise a better world than the one created by a well-meaning, all-knowing, omnipotent God? Even if humans could radically improve the world, should they? The Bible says that man is destined to live in a world of sin and death until God transforms earth into a paradise. Terrestrial life is meant to be a vale of tears—a difficult qualifying round for the one true utopia: heaven. Noyes’s belief that the Second Coming had happened in the first century allowed him to slice through this theological knot. The only reason the earth is not yet a paradise is that true Christianity (Perfectionist, communist) was lost at the end of the apostolic age. Since the Putney Perfectionists were the only people who understood the true nature of redemption, it was up to them to commence building an earthly branch of the Kingdom of Heaven. Noyes further claimed that the apostolic community of the first century was still intact in a higher sphere. He believed that the fulfillment of the millennium would somehow involve bringing his community into union with those first Jesus worshippers. He felt a particularly intimate fellowship with that apostolic latecomer Paul.

What made Noyes a utopian, rather than a raving seer like William Miller, was that he combined these supernatural beliefs about the end of history with a highly practical plan for realizing his vision. By creating an entirely new type of human community—one that enacts the biblically enumerated promises of the millennium—Noyes planned to trigger the long forestalled reign of heaven on earth. (This could be called fake-it-till-you-make-it millennialism. If you act as though it is the millennium, it will become the millennium.)

To spread the new millennial order, the Perfectionists intended to use the same basic strategy employed by their utopian contemporaries. They would build a single small utopia—a seminal prototype of the coming paradise. Its example would be so appealing that others would rapidly imitate it. Eventually, the entire world would take up the new system. Presto: heaven on earth.

But first, Noyes needed to figure out precisely what life in the millennium would look like. What, as he put it, would be the “social privileges” of life in the “resurrection state”?

Marriage Supper of the Lamb

Although his name was eventually synonymous with libertine sexuality, young John Humphrey Noyes was skittish around women. As a junior at Dartmouth, he confided to his journal that he “could face a battery of cannon with less trepidation than I could a room full of ladies.” Debilitating shyness was a family tradition. Out of sheer bashfulness, all four of John Sr.’s brothers had married women already named Noyes—cousins or “kin of some degree.”

While Noyes was still in New Haven, not long after his conversion to Perfectionism, he overcame his trepidation long enough to fall in love with an intelligent, dark-eyed Free Church congregant named Abigail Merwin. She was eight years his senior. Their spiritual connection was intense, and she became Noyes’s first real convert.

Merwin’s family disapproved of her peculiar young suitor. When Noyes left New Haven to travel and preach, Abigail renounced the new faith. When he came back to visit, she refused to see him. Noyes carried a torch for Merwin for the rest of his long life. Even at the height of the Oneida Community, when he had more lovers than anyone could be bothered to count, Noyes periodically dispatched missionaries to try to coax his first love back into the fold.

One likely reason Merwin’s family drew her away from Noyes was that by the time he began calling himself a Perfectionist, that designation already had certain unseemly connotations. Perfectionists, it was widely understood, used their self-declared sanctity as a license for sexual adventure.*11 To Noyes, a young man sometimes hampered to the point of paralysis by his moral scruples, such an idea was alarming.

At the start of January 1837, Noyes learned that Abigail Merwin had married another man. Reeling, he wrote a long, speculative letter to his friend and fellow Perfectionist David Harrison.

I will write all that is in my heart on one delicate subject, and you may judge for yourself whether it is expedient to show this letter to others. When the will of God is done on earth as it is in heaven [that is, in the millennium] there will be no marriage. Exclusiveness, jealousy, quarreling have no place at the marriage supper of the Lamb….I call a certain woman my wife. She is yours, she is Christ’s, and in him she is the bride of all saints. She is now in the hands of a stranger, and according to my promise to her I rejoice. My claim upon her cuts directly across the marriage covenant of this world, and God knows the end.

David Harrison passed the letter on to Simon Lovett, a Massachusetts Perfectionist notorious for his role in a scandal known as “the Brimfield bundling,” in which two attractive young Perfectionist women were found in Lovett’s bed attempting to demonstrate their collective triumph over sin. Through Lovett, Noyes’s private musings on this “delicate subject” ended up, without a byline, on the front page of the Battle-axe and Weapons of War, a radical Perfectionist newsletter that advocated free love.

Noyes, who never once shied from controversy, immediately claimed authorship of the Battle-axe letter in his own newspaper, The Witness. His tentative belief that monogamy was somehow unchristian—a belief clearly helped into existence by the news that Abigail Merwin was “in the hands of a stranger”—was now public knowledge.*12 A storm of censure rained down on the Putney believers. Many of Noyes’s followers and subscribers abandoned him. He came to interpret the inadvertent publication of his most private thoughts as a divine kick in the pants—God’s way of forcing him, long before he felt ready, “to defend and ultimately carry out the doctrine of communism in love.” At the time, he was a virgin.

Noyes reflexively buttressed every one of his ideas with scripture. To prop up the concept of “communism in love,” he cited the Gospel of Matthew (22:23–30), wherein a Sadducee (a member of a particular Jewish sect) attempts to stump Jesus with a tricky hypothetical scenario. The Sadducee asks the self-proclaimed Messiah what would happen if a woman, obeying the letter of Mosaic law, were to marry seven brothers in succession, from eldest to youngest, and each man were to die without leaving an heir. Which of the seven would be her husband in the resurrection? Jesus responds by saying that she will not be married to any of them: “For in the resurrection they neither marry, nor are given in marriage, but are as the angels of God in heaven.” To Noyes, the upshot of Jesus’s answer to the Sadducee was clear. In the “resurrection state,” marriage will not exist.

Amazingly, this same exact sentence was used by the Shakers to certify their prohibition on sex. Both the Shakers and the Perfectionists sought to live as though they were already “in the resurrection…as the angels of God.” The former sect could not imagine sex without marriage. So for them, no marriage equaled no sex. Noyes, on the other hand, heard nothing in Jesus’s response about sex, only a prohibition on matrimony. In the “resurrection state,” he concluded, sex will be kosher as long as it is not monogamous. This reading seemed obvious to Noyes because, like Fourier, he viewed the “exclusiveness, jealousy, [and] quarreling” intrinsic to monogamy and the “isolated” family as impediments to harmony and universal brotherhood. Such divisive, unchristian feelings could not possibly be part of God’s plan for life in the millennium. Besides, the virginal prophet reasoned, why would one of the best things in life (sex) be banned from heaven on earth? “Whoever has well studied the causes of human maladies,” Noyes wrote, “will be sure that Christ, in undertaking to restore men to Paradise and immortality, will set up his kingdom first of all in the bed-chamber and the nursery.” It is hard to imagine a better testament to the pliancy of sacred texts. The Shakers and Perfectionists looked upon the same sentence in the same translation of the same book; where one group read a commandment to abstinence, the other saw an invitation to erotic bonanza.*13 As William Blake put it: “Both read the Bible day and night, / But thou read’st black where I read white.”

The year after the Battle-axe controversy, Noyes set aside his dim view of matrimony to propose to a pious Vermonter named Harriet Holton. Holton and Noyes barely knew each other, but she had been electrified by his preaching and had periodically sent him small sums of money to keep The Witness in print. His starkly unromantic proposal addressed her as “sister” and invited Holton to be his spiritual “yoke-fellow.” He added that they could “enter into no engagements with each other which shall limit the range of our affections as they are limited in matrimonial engagements by the fashion of this world.” Apparently this sounded fine to Holton. She consented so quickly that Noyes worried that his fiancée had “imbibed the spirit of Shakerism” and expected a sexless union. She had not; she did not.

Holton’s inheritance allowed Noyes to buy a printing press and a secondhand set of type. The newlyweds spent their honeymoon in Albany, picking up the new equipment. When they returned to Putney, Noyes began to teach his followers how to compose articles, set type, and operate the press. “If we can raise up an army of effective writers,” he preached, “we shall ere long get ahead of the clergy.”

For several years after his marriage, Noyes continued to philosophize dryly about the virtues of nonmonogamous sexuality, but nothing, as it were, happened. Along with every one of his statements about sexual relations in the “resurrection state,” he reiterated his initial claim that established sexual mores could be breached only after the Kingdom of God was established on earth. Christ may have already come and gone, but the millennium was clearly not yet in full flower. The Second Coming had opened the possibility of spiritual perfection, but the world was not yet perfect.

These caveats did little to stop rumors. The Perfectionists living communally in Putney prized a high level of social intimacy. Within the tight-knit community, tender expressions of Christian love passed frequently between “brothers” and “sisters.” The upright citizens of Putney began to wonder what exactly was going on up at the Noyes farm.

George and Mary Cragin, a revivalist couple from New York City, were among the first Perfectionists to join Noyes in Putney. George was a buttoned-up Grahamite who, before his conversion to Perfectionism, had worked as an editor on the Advocate of Moral Reform, a paper that tracked signs of “moral decay” such as the rise of pornography and women working outside the home. The Advocate, which exemplified a certain strain of female-led, teetotaling, nineteenth-century reformism, singled out Noyesian Perfectionism for special abuse, calling it “a refinement of wickedness which puts papacy to the blush.” It was George’s wife, Mary, a schoolteacher with passionate religious feelings, who steered the couple toward Perfectionism. Although a surviving portrait of Mary Cragin shows a dour, large-eared woman with severely parted hair and thin lips, Noyes recalled her as being deeply sensuous. He called her a second Mary Magdalene. “Her spirit,” he wrote, “[was] exceedingly intoxicating—one that will make a man crazy.”

By 1846, Noyes had begun to wonder whether there might be a reciprocal relationship between the coming of God’s kingdom and the abolition of marriage. If free love was going to define life in the millennium, maybe free love would help trigger the millennium.

On a pleasant evening in May, Noyes and Mary Cragin took a stroll on the farm in Putney. At a “lonely place” they sat on a rock to chat. “All the circumstances invited advance in freedom,” Noyes recalled, “and yielding to the impulse upon me I took some personal liberties. The temptation to go further was tremendous. But at this point came serious thoughts. I stopped and revolved in mind as before God what to do. I said to myself, ‘I will not steal.’ After a moment we arose and went toward home. On the way we lingered. But I said, ‘No, I am going home to report what we have done.’ ”

Back at the main house, Noyes and Cragin sat down with their spouses to discuss the incident as a group. After some hesitation, Harriet Noyes and George Cragin, both of whom had already expressed a special spiritual affection for each other in letters, consented to go along with what their spouses had commenced. All four agreed to merge their two marriages into a single union. “The last part of the interview was as amicable and happy as a wedding,” Noyes recalled, “and the consequence was that we gave each other full liberty.”

The practice of what Noyes dubbed “complex marriage” soon spread, first to the Noyes siblings and their spouses and then to a few other central members of the community. They considered it a logical extension of the intense collectivism they had cultivated. They already had communism in the kitchen and the workshop. Now they had it in the bedroom. To the small circle of initiates, Noyes counseled “Bible secretiveness.” They should not lie, but they could withhold the truth.

This fledgling experiment in sexual liberty was hardly a swinging free-for-all. Only two-person heterosexual couplings were permitted. Every liaison had to have the consent of Noyes and all other relevant parties. Secrecy was strictly forbidden, as was monogamy, which the Perfectionists derisively called “special love.” The arrangement was indeed complex.

In the coming decades, as more and more people were wed into the communal marriage, the philosophical and theological underpinnings of complex marriage became more elaborate. The Perfectionists eventually came to identify sex as the holiest of human acts—simultaneously an expression of love for God, a path to transcendence, a medium of spiritual edification, and a means of dissolving the covetousness and isolation that reign in the World.

The Region of Easy Rowing

Group marriage was actually Noyes’s second erotic innovation. Like Ann Lee, who took up her “cross against the flesh” in the wake of several wrenching stillbirths, Noyes began to experiment with family planning after Harriet delivered four premature infants, all of whom died quickly. (They had one surviving child, a son named Theodore.) In 1844, two years before John’s first dalliance with Mary Cragin, he and Harriet began practicing “male continence”—sex in which the man does not climax, within or without.

The genesis of male continence goes back to New Harmony. In 1831, Robert Dale Owen, still resident at his father’s shuttered utopia, wrote an influential pamphlet titled Moral Physiology that created a scandal by distinguishing between sex for pleasure (“amative”) and sex for reproduction (“propagative”). Owen suggested that when pleasure is the main object, people ought to practice coitus interruptus (withdrawal).*14

Noyes reviewed Owen’s pamphlet approvingly in his own paper. “It is as foolish and cruel,” he believed, “to expend one’s seed on a wife merely for the sake of getting rid of it as it would be to fire a gun at one’s best friend merely for the sake of unloading it.” But unlike Robert Dale Owen, Noyes was too committed to the Bible to endorse “spilling” one’s “vital powers.” Along with coitus interruptus, this ruled out the “French method” (condoms) and masturbation, which Noyes called “the most atrocious robbery of which man can be guilty; a robbery for which God slew Onan.”

Along with Owen’s pamphlet on birth control, Noyes studied Shaker texts on abstinence. He was keen to underscore the doctrinal similarities between the seemingly opposite practices of his community and the Shakers. “The ‘system’ of Male Continence,” he insisted to a skeptical public, “has more real affinity with Shakerism than Owenism. It is based on self-control, as Shakerism is based on self-denial.”

Noyes explained the practical operation of male continence with a vivid analogy:

The situation may be compared to a stream in three conditions, viz., 1, a fall, 2, a course of rapids above the fall, and 3, still water above the rapids. The skillful boatman may choose whether he will remain in the still water, or venture more or less down the rapids, or run his boat over the fall. But there is a point on the verge of the fall where he has no control over his course; and just above that there is a point where he will have to struggle with the current in a way which will give his nerves a severe trial, even though he may escape the fall. If he is willing to learn, experience will teach him the wisdom of confining his excursions to the region of easy rowing, unless he has an object in view that is worth the cost of going over the falls.

Having uncoupled pleasure from procreation, the Perfectionist men and women spent the next few decades collectively refining their skills in the bedroom. Lingering in “the region of easy rowing,” it turned out, greatly extended sex. While the Perfectionist men diligently avoided “the propagative crisis,” the women of the community reportedly enjoyed satisfying orgasms during hour-long bouts of lovemaking. According to one woman’s recollection, the preferred sexual position within the community was with the man beside or behind the woman, so he could pleasure her with his hands. At a time when the subject of female eroticism was entirely taboo, Perfectionist women were encouraged to speak frankly about their likes and dislikes.

Trample Under Foot the Domestic and Pecuniary Fashions of the World

On the evening of June 1, 1847, Noyes announced an important shift in his thinking about how the millennium would begin. “The Kingdom of God,” he told his assembled community, “will be established here not in a formal, dramatic way, but by a process like that which brings the seasonal spring.” As human society approaches perfection, the millennium will gradually blossom. As far as Noyes was concerned, his small community in Putney had already gone a long way toward that end. “We have been able to cut our way through the isolation and selfishness in which the mass of men exist, and have attained a position in which before heaven and earth we trample under foot the domestic and pecuniary fashions of the world. Separate households, property exclusiveness have come to an end with us.” The fact that the Perfectionists had successfully overcome so much of what was wrong with the world—monogamy and private property, in particular—proved that, in a subtle way, the kingdom had already come. “Is not now the time,” Noyes asked, “for us to commence the testimony that the Kingdom of God has come?”

By then, the Perfectionists had developed the habit of voting on almost everything. After Noyes’s sermon, he asked the community to consider an unusual resolution. Therefore be it resolved: “The Kingdom of Heaven has come.” The vote in favor was unanimous. And so it came to pass that the glad millennium foretold by the Hebrew mystics was kicked off American style—by a show of hands. At the precise moment that the vote was taken, a clap of thunder shook the house. The Perfectionists took it as divine affirmation; the millennium had begun.

A month later, a Putney woman named Harriet Hall who had been bedridden for eight years with a mysterious ailment sent for Noyes. Hall could not walk and could barely see. The slightest movement caused her great pain. For three hours, Noyes and Mary Cragin prayed and spoke with her about salvation. Enthralled, Hall told Noyes that she would do whatever he commanded. He ordered her to sit up. She did. He told her to stand. She did. Mary Cragin raised the window shade, and for once, the daylight did not hurt Hall’s eyes. News of this miraculous cure—the most compelling of several faith healings attributed to Noyes—spread among New York and New England Perfectionists, helping secure Noyes’s position as the leading man of American Perfectionism.

In the wake of this widely reported cure, the citizens of Putney began turning against the Perfectionists. Matters were made worse when one of Noyes’s brothers-in-law attempted to convert a local fifteen-year-old named Lucinda Lamb—one of “the flowers of the village.” Lamb’s father, who originally consented to her worshipping with the Perfectionists, suddenly changed his mind. Around the same time, a local Methodist minister named Hubbard Eastman began agitating against the community. He wrote a thick volume titled Noyesism Unveiled: A History of the Sect Self-Styled Perfectionists, which identified Noyes as “a hideous monster of iniquity” and called his small community “as corrupt and shameless as THE MOTHER OF HARLOTS AND ABOMINATIONS.”

Noyes then made a crucial misjudgment. He tried to initiate Daniel Hall, husband of the faith-healed Harriet, into the privileges of complex marriage. Disgusted, Hall rode to Brattleboro to file a complaint with the state’s attorney. A warrant was issued, and on October 26, 1847, Noyes was arrested and charged with having “carnal knowledge” of two women not his wife.

There was a preliminary hearing in the local tavern. After freely admitting to having sex with the women, Noyes was released on a $2,000 bond. Before the actual trial commenced, Larkin Mead, one of John’s non-Perfectionist brothers-in-law, learned that the state intended to prosecute Noyes and several of his male followers to the full extent of the law. Mead also heard disturbing rumors of a plan to drive the Perfectionists from Putney by force. Despite the fact that he had personally paid Noyes’s substantial bond, Mead advised his brother-in-law to jump bail and leave Vermont at once.*15 Reluctantly, Noyes conceded. Those Perfectionists who were not originally from Putney scattered, too, awaiting counsel from their fugitive prophet.

Oneida

In a shallow, secluded valley at the center of the Burned-over District, a Perfectionist couple named Jonathan and Lorinda Burt lived on a forty-acre woodlot, bounded on three sides by a wide, bell-shaped curve in Oneida Creek. The land was part of a reserve held by the Oneida tribe until 1840, when the state of New York bought it and began selling plots to white settlers. There were a few small farms near the Burts’ place, but it was wild, densely forested country. Along with three other couples, the Burts lived much as the Shakers had during the early years at Niskeyuna. They shared two farmhouses and some old Indian cabins, operated a sawmill, and gathered nightly around the flame of their Perfectionist faith.

When Burt heard that the Putney community had been scattered, he invited Noyes to come stay. Noyes, who had previously met Burt at a Perfectionist conference, visited the land and liked what he saw. Compared with the nosy, puritanical village of Putney, the wilderness of central New York—home to Shakers, Mormons, Millerites, Fourierists, and plenty of Perfectionists—was a heretic’s paradise, a Penn’s Woods for the nineteenth century.

Noyes’s abiding sense of biblical drama was aroused by the thought of leading his people into the wilderness. He sent a letter to George Cragin announcing that he had found the perfect place for their “spiritual phalanx.” “There is some romance,” he wrote, “in beginning our community in the log huts of the Indians.” Over time, Noyes wrote, they could build themselves a Perfectionist “chateau.” Having just jumped bail in Vermont, he probably noted the convenient proximity of the Canadian border.

On the evening of March 1, 1848—while the Icarian avant-garde crossed the Atlantic—the nucleus of the Putney community arrived by train at the Oneida depot. As a heavy snow fell, they traveled the three miles to their new home by sleigh. Other Perfectionists trickled in over the next few months. They pooled their money, bought the land adjacent to Burt’s property, and named their new community the Oneida Association.

Even before the Putney believers showed up, the region around Oneida Lake was a hotbed of Perfectionism. About 40 percent of the subscribers to Noyes’s Witness lived in the Burned-over District, and three-quarters of them lived within thirty miles of Oneida Lake. When these people heard that a Perfectionist community was being started, many were eager to join. A year after Noyes’s arrival, there were a hundred people living on the property. In three years, there were more than two hundred.

The people who came were mostly artisans. Among the first wave were printers, cabinetmakers, tinkers, shoemakers, coopers, bakers, and carpenters. Only a few were farmers. The majority entered the community as families or as couples in their twenties and thirties. New members may have been aware of the scandal in Putney, but most did not know about the doctrine of complex marriage. Whatever drew them to Oneida, it wasn’t libidinous curiosity.*16

Whereas many of the Owenite and Fourierist communities had been divided over secondary issues such as “Sabbath breaking” and vegetarianism, the Oneida Community was blessed from the outset with a population unified by their strong faith in Noyes’s socioreligious doctrines. While small utopias often suffocate under reams of bylaws, Noyes insisted that the proliferation of written rules—what he called “legalism”—was anathema to Perfectionism. He claimed that the descent of Christianity into “the Apostasy”—the long, dark age between the demise of the primitive church and the birth of his own community—paralleled the rise of a bureaucratic, rule-making religious establishment and the subsequent atrophy of the living inspiration.*17 He believed that written ordinances inevitably muffle the small voice of inspiration that is the only true authority.

Noyes did not have a monopoly on revelation. The Oneida colonists believed that God could speak through the community as a unified whole, that inspiration—or “afflatus,” as they called it—was often a collective experience. While Noyes generally had the final word on matters of religious doctrine, most major decisions—what type of home to build, which industries to pursue, where to dig the privy—were settled by lively, community-wide debate. Meetings were held daily, and consensus was the constant goal. As a leader, it was Noyes’s habit to appoint lieutenants (both men and women) to oversee practical matters. During the early years at Oneida, John Miller, the husband of Noyes’s sister Charlotte, did much of the daily administration of the community, freeing Noyes to think and write.

By the start of 1849, the Oneida Association owned 160 acres of woods, swamp, and pasture. They set up a shoemaking shop, a smithy, new mills, a farm, and a community store. No wages were paid. Room, board, child care, and education were considered compensation for all the labor performed. The early years were lean. The settlers cleared stone from their fields, built walls, and drained the boggy areas near the creek. Food—at first mostly coarse bread, milk, beans, and potatoes—was limited. During the first summer, dysentery swept through the community.

Nineteenth-century American utopianism is often understood as a long, slow conversation between, on the one hand, millenarian sects such as the Shakers and the Rappites and, on the other hand, secular utopians such as Owen, Cabet, and Fourier.*18 The religious sects—inspired by the Bible’s account of primitive Christianity and the practical demands of rural separatism—created a communal prototype that the secular visionaries blended with Enlightenment-born ideas about rational planning, gender equality, and social progress. At Oneida, where the Perfectionists studied both Fourier and the Old Testament, the pendulum swung in the opposite direction; the utopian socialists helped inspire a community devoted principally to spiritual ends.

Noyes saw a direct connection between the rise of his community and the ebb of American Fourierism. “The Oneida Community owes much to Brook Farm,” he wrote. “Look at the Dates. Brook Farm deceased in October 1847. The Oneida Community commenced in November 1847. It is a simple case of transmigration, or in the latest language, persistence of force.” Later, he called Oneida the “continuation” of Brook Farm. Noyes thought that the utopian socialists had failed for many reasons, but chief among them was their neglect of God. He wrote, “Owen, Ripley, Fourier, [and] Cabet…left God out of their tale and they came to nothing.”

The Fourierist phalanxes had mostly been organized as joint-stock corporations. The Oneida Community, like the Shaker villages and the various Icarias, opted for “communism pure and simple.” Private property was totally abolished. New members sold everything they owned—homes, land, animals—and put the proceeds into a common pot. A record was kept of what everyone contributed, and when a member left, as more than a few did, they were refunded their initial contribution, without interest. The land at Oneida, as well as the livestock, the tools, the linens, and the food, was collectively owned. Even pocket watches belonged to the commonwealth. Unlike at New Harmony and the North American Phalanx, nobody wrote down who ate what. If a woman needed a dress, one was made from the common stock of calico or bought with common cash. When a Perfectionist invented a marketable product, the profits went to the collective. Of course, the most extreme expression of this commitment to radical, all-encompassing collectivism was the sexual communism of complex marriage, in which every adult man in the community was understood to be married to every adult woman.

Brisbane and Ripley claimed that the constraints built into pure communism posed an unacceptable threat to individual liberty. In doing so, they defined freedom in the usual American sense, as the absence of external constraints, what Isaiah Berlin termed “negative liberty.” Noyes thought this conception of freedom was wrongheaded. He called it the freedom of the porcupine—the right of people to stay away from one another. As an alternative to the freedom of the porcupine, Noyes offered “the liberty of communism,” which he defined as the freedom “to approach one another and to love one another.” In a very practical sense, this “liberty of communism” also meant freedom from uncertainty, hunger, and solitude.

Like Ripley, Noyes expected his community to resolve the antithesis between individual liberty and mutual aid. He wrote: “The two great principles of human existence, solidarity on the one side, liberty on the other, are in their nature harmonious, although the forces concerned in them are apparently antagonistic, like the centripetal and centrifugal forces in nature. They are designed to act upon human life in equilibrium….The philosophy of Christ and of reason, teaches that liberty is the result of solidarity; that we are not to seek liberty directly, but to seek first solidarity, and liberty as the fruit of it.”

Noyes used the term Bible Communism to describe every aspect of his philosophy, from the abolition of private property to complex marriage. While the coupling of the words Bible and communism was less jarring before the advent of explicitly “godless” communism, there was already a measure of hostility between socialists and revivalists in the middle nineteenth century.*19 Noyes found this antipathy baffling. To him, the acquisitive, tooth-and-claw nature of capitalism was patently irreconcilable with the teachings of Jesus and the example of the primitive church. Like every generation of radical Christians, Noyes read the New Testament as a manifesto for upending the existing social order. “When the Spirit of Truth pricked three thousand men to the heart and converted them on the day of Pentecost,” he wrote, “its next effect was to resolve them into one family and introduce Communism of property. Thus the greatest of all Revivals was also the great inauguration of Socialism.”

Inspired by Owen’s parallelogram and Fourier’s phalanstery, the Perfectionists decided that some sort of “unitary dwelling” was essential to their plan of living as one unified family. In 1848, on a low knoll at the center of their estate, they built a wooden, hotel-sized building. Noyes personally laid much of the foundation. After considering and rejecting the terms phalanstery and communistery, they decided to call the building “the Mansion House.” It was an odd choice for a band of separatists living in the wilderness, but it perfectly fit the building and the lifestyle that the Perfectionists created for themselves over the coming decades.

Winter came before the Mansion House was finished. The entire community moved into a single room on the second floor. In the center of the space, they installed a stove and a sitting area. The rest of the room was divided into small “bedrooms” with sheets hung from ropes. For decades, the communists recalled the cozy winter they spent in “the tent room” as a halcyon age of communal harmony and intimacy. For outsiders, this months-long slumber party provided the germ for the absurd but persistent rumor that the Perfectionists all slept in a single bed.

The Mansion House was expanded over the next ten years. In 1860, the three-story building was torn down and replaced with a larger, redbrick structure, also called the Mansion House. The Perfectionists remained in a nearly constant state of demolition and construction. Like all the other utopians of the era, they realized that the shape of rooms and halls defines the shape of social relations. They rearranged their estate with such frequency that a local carpenter suggested they put their buildings on casters. This never-ending pursuit of the ideal physical domain reflected the community’s approach to pretty much everything: ceaseless refinement through trial and imagination.

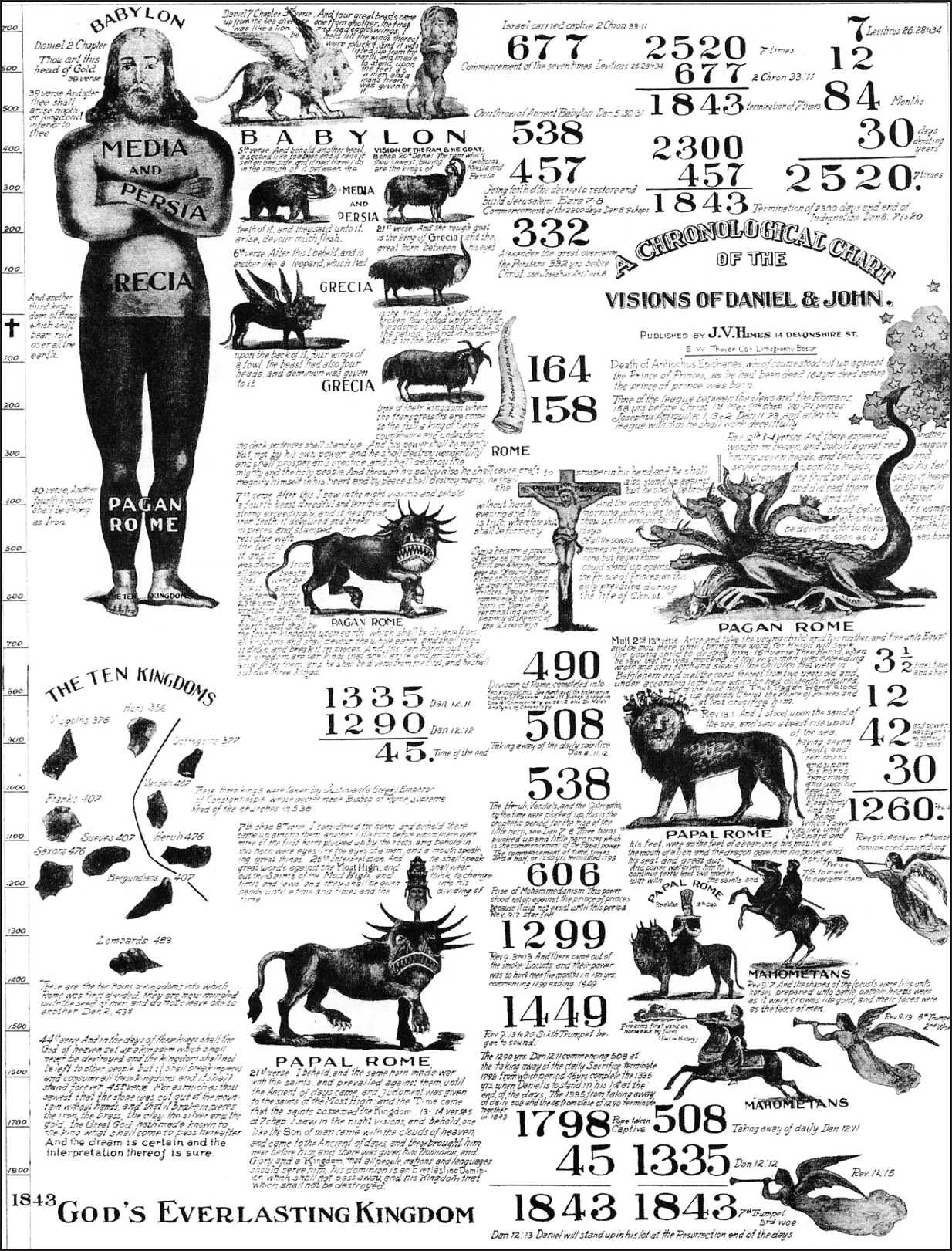

By the 1870s, the Mansion House was huge—a rambling U-shaped complex with slate roofs and a grand, pillared entrance. The building, which enclosed a small grass quad, had two large towers, a cavernous auditorium, and 475 rooms. It looked (and still looks) like the ivied hub of an elite New England college. Most adults slept in their own narrow, cell-like rooms, but every floor had parlors, reading rooms, and libraries, all of which served the community’s architectural maxim that “the balance of inducement should always be toward aggregation and not separation.”*20

The Mansion House.

© Oneida Community Mansion House, Inc. All rights reserved.

A Two-Legged Animal

To the surprise of the Oneida Community’s neighbors, Perfectionist women did much of the carpentry on the first Mansion House. At a time when the male and female spheres of labor were drifting apart, the Perfectionists deliberately mixed things up. Men ironed sheets in the laundry; women hammered iron in the metal shop. Noyes can hardly be counted as a feminist—he claimed nominal allegiance to Saint Paul’s chauvinist statements about man’s natural dominion over woman—but he believed that “worldly” society made too much of the innate differences between the sexes. The idealized Victorian woman was a paradoxical mix of fragility and fertility. In almost every respect, the feminine ideal at Oneida was that Victorian lady’s opposite number. She was supposed to be intellectually assertive, physically robust, sexually frank, and totally indifferent to mothering.

Noyes partly blamed fashion for exaggerating the physical differences between men and women. Women’s dress, he wrote, is “a standing lie [that] proclaims that she is not a two-legged animal but something like a churn, standing on castors!” Not long after the Perfectionists arrived in Oneida, Harriet Skinner (Noyes’s sister), Harriet Noyes, and Mary Cragin gathered to design a less churnlike costume for themselves. The result was a long-sleeved blouse and a matching knee-length skirt worn over loose “pantalets.” They called it “the uniform of a vital society.” After some snickering, all of the women in the community adopted it. This so-called short dress was soon supplemented with elastic sneakers, which, like true utopians, they called “the final shoe.” After a group of Perfectionist women were harassed at Grand Central Terminal, the community began to keep a few traditional dresses on hand for traveling.

Despite a midcentury vogue for elaborate updos, the women at Oneida cut their hair shoulder length or shorter, a style then associated with adolescent girls. While their sisters in the World routinely spent an hour arranging combs, pins, and extensions atop their heads, the women of Oneida boasted that they went directly from bed to the breakfast table. “Any fashion which requires women to devote considerable time to hair-dressing,” they announced in the community paper, “is a degradation and a nuisance.”*21 Having freed themselves from the tyranny of girdles, toe-binding boots, and waist-length hair, the Perfectionist women were able to participate fully in the physically active life of the community.

While the community came under constant attack for its economic and sexual communism, nothing seemed to excite as much outrage as the appearance of female Perfectionists. Among outsiders, it was stated as a matter of settled fact that the women of Oneida were ugly. The evidence given for this supposed homeliness says more about the tastes of the day than the relative good looks of the communists. Compared with the tottering, neurasthenic delicacy that was then regarded as the height of feminine beauty, the hardworking, sports-playing women of Oneida were seen as unattractively tan and hale. Uncorseted, they lacked the stiffness of carriage expected of fashionable women.

The women of Oneida claimed that their outdoorsy, teetotaling, childless existence kept them young. “We women of thirty are often mistaken for Misses [because] we are saved from so much care and vexation.” When they read about the new trend of “enameling”—a practice in which the female face was plastered with a rigid layer of putty and then painted over in red and white—they were horrified. “People sneer at our dress, and talk slightingly of our looks, but, alas! They know not what they say. We have no ‘heavers,’ nor ‘plumpers,’ nor ‘false calves,’ nor ‘rouge’; and perhaps we don’t look as well as your city belle who is puffed and padded and painted; but we are genuine from head to foot.”

Although the Perfectionists practiced many of the social reforms that were only being discussed elsewhere, they felt surprisingly little kinship with secular reformers, even when those reformers were their neighbors.*22 The year that the community moved to Oneida, Lucretia Mott, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Frederick Douglass, and a group of progressive female Quakers met at nearby Seneca Falls for the convention that launched the crusade for women’s suffrage. While tracts by the likes of Stanton and Susan B. Anthony circulated in the Mansion House library—and Anthony actually visited the community—the communists insisted that their feminism derived from revelation and their own experimentation, not the “imported ideas” of “worldly reformers.” In the 1860s, a group of community women started an “express service” to convey visitors and packages back and forth between the mansion and the nearby train depot. The venture presented local non-Perfectionists with the jarring sight of “unattended” women in sporty dresses and childlike haircuts loading parcels, wrangling horses, and operating a prosperous enterprise. The community journal described the venture as a triumph for “women’s rights” but put the phrase—a newcomer in the national lexicon—between scare quotes, adding: “ ‘Woman’s Rights,’ is a term we always prefer to quote as borrowed; it is not indigenous in the nomenclature of the Community.”

Like almost all nineteenth-century utopians, the Perfectionists believed that the narrow, superseding loyalties engendered by marriage and the biological family were anathema to progress, particularly female liberation. Owen identified marriage as the main impediment to female equality. Fourier called it “the germ of falsity and immorality.” The Shakers, by deed if not declaration, seemed to agree. Noyes hoped that complex marriage would free women from both matrimony and motherhood, thereby revealing capacities obscured by their traditional status as chattel. Under the Oneida system, he wrote, “women are not men’s slaves, but loosened from the bondage of marriage, are set free to criticize men and express their own tastes and feelings.”

The Infantile Population

Complex marriage did away with the idea that women are the property of their husbands. Male continence freed them, for better or worse, from motherhood. The Perfectionists’ ongoing effort to prevent insemination did not reflect any sort of Malthusian scruples or religious opposition to breeding. “We are not opposed, after the Shaker fashion or even after [Robert Dale] Owen’s fashion, to the increase of the population,” Noyes wrote. “We are opposed to random procreation which is unavoidable in the marriage system.” In fact, male continence was one of the few things at Oneida that lacked an elaborate theological underpinning. The Perfectionists spoke about birth control in familiar terms. It was a matter of health, practical economy, and women’s rights. A community notice from 1858 declared that “child-bearing, when it is undertaken, should be a voluntary affair, one in which the choice of the mother, and the sympathy of all good influences should concur. Our principles accord to woman a just and righteous freedom in this particular, and however strange such an idea may seem now, the time cannot be distant when any other idea or practice will be scorned as essential barbarism.”

The community’s unusual method of birth control was surprisingly effective. Among roughly two hundred sexually busy adults, there was, on average, about one accidental pregnancy each year, a rate that compares favorably with that of modern birth control pills.*23 Those few men who were unable to master male continence were paired with those women who were, in the poignant euphemism of the day, “past the time of life.” In 1852, the Circular boasted that “the increase of population by birth, in our forty families, for the last four years, has been considerably less than the progeny of Queen Victoria alone.”*24

Until 1869, when the community began its experiment in controlled breeding, most of the children at Oneida were brought into the community when their parents converted. They were raised collectively. Infants were reared and nursed by their biological mothers until fifteen months. From then until they turned twelve, they lived in “the Children’s House,” where specially assigned nurses, teachers, and guardians looked after them. Those babies who were born in the Mansion House, either by accident or by special dispensation, were formally welcomed into the fold with a community-wide naming ceremony. Their biological parents would suggest a name, and then the entire community would approve it in “recognition of the Community sponsorship” of the child.

Parents usually maintained a close relationship with their offspring, but excessive intimacy was discouraged. The sin of demonstrating too much parental attachment was known as “philoprogenitiveness,” and it was considered “as blind a passion as ever [romantic] love was represented to be.” So-called special love, either between lovers or between a parent and a child, was thought to turn the individual away from God and community. For women, motherhood was considered an overwhelming distraction from “self-culture and the appetite for universal improvement.” Of course, many people found these prohibitions painful. Some left because of them. Others welcomed communal loving and communal parenting as a liberation and a means of advancing real gender equality.

Inside the Children’s House, young Perfectionists were actively communized. To foster the “Pentecostal spirit,” their homemade dolls, wagons, and hobbyhorses were held collectively in one room. In community publications, the children are invariably described as a “herd” or “flock.” They sang together, learned their numbers together, and went boating together at the community’s lake house. Adult Perfectionists turned out in big numbers to watch the “weekly ablution of the infantile population.”