COUNTER-ATTACK

"I believe in the meaning of honor and integrity. I am an action person who feels personally responsible for making any changes in this world that are in my power . . . because if I don't, no one else will."

— Mike Spann, excerpt from his CIA application

"The Bible says there is a time for peace and a time for war. Now is the time for war. I cannot wait to say it is now a time for peace."

— MAJ James Brisson, Chaplain, 1-160th SOAR, 19 October 2001, Afghanistan

Within hours of the 9/11 attack, operations officers inside the Central Intelligence Agency headquarters in Langley, Virginia, and military planners at U.S. Central Command headquarters in Florida and at the heavily damaged Pentagon were working on how the U.S. could strike back against the perpetrators. Finding those responsible wasn't a problem.

Osama bin Laden's Al Qaeda terror organization proudly claimed "credit" for the vicious attack on several radical Islamic Web sites—and eventually in a videotaped interview. But getting at him proved to be a monumental task. When his "hosts," the brutal Taliban regime in Afghanistan, refused to hand him over, plans to remove the Taliban from power and dismantle Al Qaeda were put in motion.

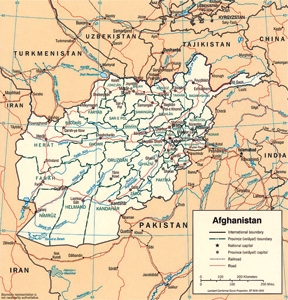

Less than seventy-two hours after the attack, U.S. Navy carrier battle groups, amphibious task forces with embarked Marines, and attack submarines with Tomahawk cruise missiles were on the way to the Persian Gulf. U.S. Air Force B-1 and B-52 bombers, outfitted with the newest guided munitions, were dispatched to the U.S. base on the island of Diego Garcia in the Indian Ocean. But the greatest challenge remained: how to get adequate U.S. military force into land-locked Afghanistan.

It was never expected that the Iranians would help, but even American "allies" in the region refused any overt assistance. The Saudis, long supporters of the Taliban regime, denied the use of their air bases to U.S. combat aircraft, even though we had rushed to defend them in 1990 when Saddam invaded Kuwait. Pakistan was more helpful. Though Islamabad had also supported the neighboring Taliban regime, General Musharaff of Pakistan secretly agreed that U.S. forces could transit Pakistani territory to get into Afghanistan as long as U.S. forces were "invisible" and his government had "plausible deniability."

Others in the region were more forthcoming. U.S. diplomats and military officers quietly arranged overflight rights with Turkey, winning agreement for quietly establishing U.S. air and logistic support bases in the former Soviet republics of Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. In the Persian Gulf, Bahrain, Kuwait, and Oman granted permission for U.S. forces to overtly use their soil.

The plan adopted at U.S. Central Command—headquartered at McDill Air Force Base in Florida and endorsed by the Joint Chiefs of Staff and Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld—took all this into consideration. Less than a week after the 9/11 attack, President Bush approved the outline for an unconventional warfare operation to unseat the Taliban and destroy Al Qaeda. It would come to be called Operation Enduring Freedom.

The regime that the U.S. targeted in Kabul was easily one of the most brutal on earth. From 1992 to 1996, the Taliban had waged a bitter civil war against the fractious Mujahadeen of the United Islamic Front (UIF) that had driven the Soviets out of Afghanistan. When they finally took power in the capital, Taliban theocrats, led by the eccentric Mullah Mohammed Omar, imposed absolute Islamic law over the Afghan population within their control and rewrote the rogue-state rule book on repression.

Universities and museums were closed. Girls were forbidden to go to school. Women were required to cover themselves completely with a burka and denied the right to work outside the home or even travel unless accompanied by their husband or a male relative. All music, television, dancing, and public entertainment were banned. Islamic courts enforced the law with public beatings, amputations, hangings, and beheadings—often carried out as public spectacles.

To some, the Taliban's worst offense was the destruction of the cliffside Buddhas in the Bamyan Valley. These were fifteen-hundred-year-old sculptures carved in sandstone. But in reality, the Taliban's greatest crime was to provide refuge and support to a radical Saudi multimillionaire, already well established as a radical Islamic terrorist: Osama bin Laden.

From 1996 to 2001, under the patronage and protection of the Taliban, bin Laden's Al Qaeda grew into a powerful global network of terrorists from every Islamic country on earth. In radical mosques, "cultural centers," charities, and madrassas—many of which he founded—bin Laden found willing recruits for his Jihad. The Taliban provided a safe place to train and direct them. By September of 2001, Al Qaeda "holy warriors" from Saudi Arabia, Egypt, the United Arab Emirates, Palestine, Lebanon, Chechnya, and Pakistan were serving as the Taliban's "palace guard." And Osama had already set in motion everything necessary for the 9/11 attacks. As we learned too late, it had all been plotted and planned from his Afghan sanctuary.

On 20 September President Bush, in a televised address to a joint session of Congress, demanded that the Taliban turn over bin Laden and all other Al Qaeda leaders, close the Afghan terror camps, release all foreign hostages, and allow U.S. inspections to ensure compliance. The Islamic radicals running Kabul rejected this ultimatum less than twenty-four hours later.

Over the course of the next two weeks, U.S. military Special Operations teams and CIA paramilitary officers were moved into position to support an offensive by the UIF, now dubbed the "Northern Alliance." Equipped with sophisticated satellite communications equipment, they reported to Central Command and CIA headquarters that, despite the assassination of one of its most effective leaders, the Northern Alliance was ready to move against the Taliban.

On 9 September, just two days before nineteen of bin Laden's radical Islamists hijacked four airliners in the U.S., three other Al Qaeda suicide terrorists posing as a TV crew detonated a bomb that severely wounded Ahmed Shah Massoud. He was the most effective, pro-Western leader in the anti-Taliban coalition. Massoud died of his injuries three days later, and Mohammed Fahim, a fellow Tajik, took over as the military leader of the Northern Alliance. Though less than certain of Fahim's ability to control this fractious anti-Taliban coalition, both the CIA and Special Operations Command officers on the ground sent a "good to go" signal back to Washington.

By the first week of October even Mullah Omar and the Taliban elite in Kabul were aware that their days could be numbered. Late on Saturday, 6 October, the Pakistani government informed Washington that the Taliban would be willing to put bin Laden on trial before one of their "Islamic courts" if the U.S. could provide "proof" of his complicity in the 9/11 attacks. President Bush immediately rejected this proposal as a delaying tactic and ordered the commencement of military operations.

29 September 2001

President Bush:

"This war will be fought wherever terrorists hide or run or plan. Some victories will be won outside of public view, in tragedies avoided and threats eliminated. Other victories will be clear to all. Our weapons are military and diplomatic, financial and legal."

Aviation ordnancemen load a two-thousand-pound joint direct attack munition (JDAM) bomb on an aircraft.

The first strikes, on the night of 7 October 2001, were near-simultaneous raids on Taliban air defenses, command, control, and communica-tions nodes and suspected Al Qaeda bases by sea-launched Tomahawk cruise missiles, B-1 and B-52 bombers from Diego Garcia, and U.S. Navy and Marine aircraft operating from carriers in the Arabian Sea and the Gulf of Oman. In just two nights of heavy precision bombing, the Taliban lost all their anti-aircraft radars and missile systems except for man-portable machine guns and surface-to-air missiles.

Within forty-eight hours of the start of hostilities, U.S. aircraft were roaming freely, day and night, over Afghanistan, dismantling the Taliban's military power with some of the most sophisticated weapons in the U.S. inventory. B-2 "Spirit" stealth bombers made scores of nonstop round trips from their bases in Missouri to drop precision guided munitions on Taliban and Al Qaeda positions. Armed Predator drones loitered over the landscape, sending "real time" streaming video to U.S. commanders searching for "high value" targets. And from bases in Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan, now protected by U.S. Army Rangers and elements of the 10th Mountain Division, intelligence officers "listened in" on Taliban and Al Qaeda satellite and cellular telephone communications.

A B-2 Spirit stealth bomber

A B-1 bomber being refueled by a KC-135 Stratotanker

An Air Force MQ-1B Predator goes out on patrol

On the ground, the Northern Alliance—bolstered by U.S. Special Forces teams equipped with night vision devices, laser target designators, and satellite communications equipment—moved to exploit the Taliban-Al Qaeda disarray. Afghans were awed by the ability of the U.S. to put "smart bombs" on target—more than two thousand of them—and by the visible presence of Americans in the fight. Thousands rallied to the Northern Alliance.

Army PVT Robert Sheppard, a heavy weapons specialist, scans the horizon while on patrol outside Kandahar Air Base, Afghanistan

By 21 October, two weeks after the initiation of hostilities, Afghanis who had once fought for opposing "war lords" against one another were flocking to join the anti-Taliban cause. Many of them, particularly in the south, joined to help evict "the Arabs"—meaning Al Qaeda—from their country. Many in the media predicted that Afghanistan's fabled ethnic and tribal rivalries would prevent a cohesive campaign against the Taliban. But one member of the Special Operations forces summed it up this way: "You don't have to beat 'em if you can buy 'em."

On 9 November Northern Alliance forces, supported by U.S. Special Forces—some on horseback—drove the Taliban and their Al Qaeda allies out of their provincial stronghold at Mazar-i-Sharif. Three days later, Alliance troops were in Kabul, and the Taliban were in retreat to the southern city of Kandahar and the Afghan-Pakistan border with the Northern Alliance and their U.S. counterparts in hot pursuit.

Northern Alliance soldiers were essential in toppling the Taliban

As the Americans and their Alliance allies moved deeper into the country, the magnitude of what the Afghan people had been suffering for years became painfully evident. Tens of thousands of civilians were fleeing the fighting, and the onset of winter was just weeks away. To alleviate their suffering, President Bush ordered air drops of food, water, and relief supplies and established America's Fund for Afghan Children. In response to his appeal for each American child to donate a dollar, millions were raised. When the first shipment was sent to Afghanistan on 10 December 2001, it included 1,500 winter tents, 1,685 coats, and 10,000 packages containing hats, socks, toothbrushes, candy, and toys.

All of this was accomplished without the loss of a single American killed by the enemy. But that was about to change.

An Afghan man and his son transport hay for making bricks

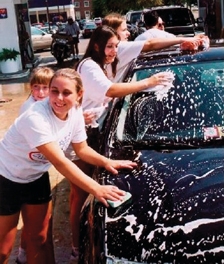

While bombs were still being dropped on Taliban and Al Qaeda holdouts, the U.S. government delivered more than $250 million in humanitarian aid to the people of Afghanistan. The Taliban responded by warning the refugees that the food was poisoned. Much of our mainstream media reaction was to point out that errant U.S. bombs had also killed civilians. Thus most of the cameras missed poignant stories such as that of Ashley, Aubrey, Alana, and Alyssa Welch. Their father, LTC Tracy Welch, had narrowly escaped the crash of American Airlines flight 77 into the west wall of the Pentagon on 9/11. When the girls attempted to donate blood, they were told that they were too young. So they organized four neighborhood car wash events and raised $10,000.

American forces supporting the Northern Alliance troops included members of the CIA's ultrasecret Special Activities Division (SAD). Johnny "Mike" Spann was among them.

After rising to the rank of captain in the Marine Corps in 1999, Mike joined the CIA and became a member of the agency's paramilitary unit in the Directorate of Operations. Dozens of paramilitary officers—the actual number is still classified—were dispatched to Afghanistan to assist U.S. Special Operations forces in equipping, arming, training, and supporting the troops flooding into the Northern Alliance. After the attack on 9/11, Mike Spann was among the first in the SAD to volunteer for duty in Afghanistan.

During the last week of September, SAD operatives were deployed to establish a forward base for military Special Operations detachments which soon followed. Once on site, Mike and his teammates "vetted" Afghanis for duty with the Northern Alliance, organized intelligence collection and analysis cells for operations against the Taliban and Al Qaeda, and conducted counter-intelligence activities.

During the fight for Mazar-i-Sharif, more than three hundred Taliban fighters surrendered and were taken into custody by Northern Alliance forces and imprisoned in the city's nineteenth-century fortress. Because the detainees had potential intelligence value on the capabilities and whereabouts of key Taliban and Al Qaeda kingpins, SAD officers were assigned the task of interrogating them.

Northern Alliance soldiers

On 25 November, Mike Spann and his partner arrived at the prison and began to conduct interrogations. That's how they discovered that one of the detainees wasn't an Afghan at all. He was an American named John Walker Lindh. According to Lindh, he was a convert to Islam and had traveled first to Pakistan and then to Afghanistan with the intention of joining Al Qaeda.

Shortly after being interrogated by Spann, Lindh and his fellow prisoners overpowered their guards and murdered Mike Spann with two gunshots to the head, making him the first American casualty of the War on Terror.

Mike Spann was thirty-two years old when he died at the hands of a murderous countryman who had joined the Jihad. Mike left behind his widow, Shannon Spann, an infant son, and two young daughters.

Mike Spann's family at Arlington National Cemetery

The same day that Mike Spann was killed in the Mazar-i-Sharif prison uprising, the first U.S. "conventional forces"—the 15th Marine Expeditionary Unit (MEU)—landed in Afghanistan. Over the course of four days and nights, I was given the unique opportunity to document, firsthand, just how sensitive and difficult this entire operation was. A brief chronology of my journey reflects the extraordinary challenges in this campaign and how creative and courageous young Americans overcame them.

The concept of "embedding" correspondents with combat units had not yet been "re-invented" at the Pentagon. This meant that dozens of reporters and broadcast news crews were "stranded" in Bahrain waiting for clearances and credentials that would allow them "in-country." Some caught commercial flights to Pakistan and braved the dangerous overland drive across the border into Afghanistan. Not all of them made it.

Since my job was to document how Americans fight, FOX News dispatched me and Executive Producer Pam Browne to the headquarters of the U.S. Fifth Fleet. This was the naval component—made up of ships, sailors, and Marines—for the U.S. Central Command. As soon as we arrived in Bahrain, I called on an old friend and Naval Academy classmate, Vice Admiral Charles W. "Willie" Moore, the Fifth Fleet's commander. In a matter of minutes, he arranged for me to link up with U.S. forces heading into Afghanistan.

A Navy C-2 prepares for takeoff

Before dawn we arrived at the Bahrain Naval Air Facility to catch a Navy C-2 "COD" for the three-hour flight to the USS Theodore Roosevelt (CVN-71) in the Arabian Sea. The twin-engine turbo-prop, packed with replacement personnel and critically needed equipment, was hastily offloaded when we reached the Theodore Roosevelt's flight deck so strike aircraft could continue to launch and recover.

For the entire twelve hours we were aboard the "Big Stick," the nuclear-powered carrier launched and recovered a near-continuous stream of bomb-laden F-14 Tomcats and F-18 Hornets for their six- to eight-hour-long missions over Afghanistan. Once on station, the aircraft would either carry out preplanned strikes on known Taliban-Al Qaeda targets or provide "on-call" air support for U.S. Forward Air Controllers accompanying Northern Alliance troops. To support every strike mission, the flight deck crews also launched aerial refueling tankers, airborne command and control aircraft, electronic warfare birds, and search-and-rescue helicopters. All of these had to be "recovered." Then the cycle would begin all over again—twenty-four hours a day, every day.

After a few hours of sleep—directly beneath the flight deck steam catapults—I was summoned to the air group ready room and told that a helicopter would be arriving shortly to take us to the USS Bataan (LHD-5), one of our Navy's newest amphibious assault ships for the next step closer to Afghanistan. Our FOX News crew would be allowed to accompany a team of Navy doctors and medical corpsmen, as long as we abided by certain guidelines:

• We could not reveal where we landed until such time as we were authorized to do so.

• We could not identify the unit that we were accompanying until allowed.

• No mention could be made of any future plans or operations.

We readily agreed to these conditions and packed up. Less than an hour later we were aboard a thirty-one-year-old CH-46 "Sea Knight" helicopter for the sixty-mile over-water flight to the Bataan.

USS Bataan

At 844 feet long, the USS Bataan is more than two hundred feet shorter than the Teddy Roosevelt, but no less busy. In the brief time we were aboard, the warship took on food, fuel, bombs, ammunition, and spare parts from the USS Detroit, launched and recovered AV-8 Harriers for strikes against targets in Afghanistan, and coordinated the movement of an entire Marine infantry battalion into Afghanistan.

As darkness began to close in over the Arabian Sea, a Navy lieutenant led me below deck, handed me three life vests, pointed to the two doctors from the medical team, and said, "I know this isn't your job, Colonel, but show the docs how to put these things on. They're probably great surgeons, but they've never been to sea before."

Fifteen minutes later we were aboard the Bataan's two high-speed air cushion landing craft (LCACs) as they spun up their jet turbines for the forty-knot, thirty-minute trip to the venerable USS Shreveport (LPD-12), a ship that I had been aboard many times before.

When we arrived at the Shreveport's darkened well deck, Marine and Navy embarkation personnel were ready with trucks already loaded with tons of weapons, ammunition, food, water, and equipment. They had everything the Marines would need for fifteen days without reinforcements or resupply at Forward Operating Base "Rhino," their code word for the air base outside Kandahar. As the vital equipment was being loaded aboard the two LCACs, a Marine gunnery sergeant took me aside, handed me a flak jacket and Kevlar helmet, and said, "Everybody has to wear one, sir." He then added, "I understand that the doctors with you have never done this before. Please make sure they put their 'flaks' over their life vests, just in case y'all go swimming."

I decided not to tell the two medical officers about the swimming part, but I did make sure their flak jackets were on top of their life jackets.

I need not have worried. Once all the equipment was loaded and it was totally dark, our LCAC pilot, a Navy chief, donned his night-vision goggles (NVGs) and we headed inland from over the horizon, flying at almost fifty knots without lights across the surface of the water.

When we arrived at "Red Beach," Navy and Marine shore party personnel leapt to the task of unloading all the supplies, personnel, and equipment; organized it all into a well-protected convoy; and trucked everything to a small but well-guarded airfield less than ten miles inland. Just moments after we arrived alongside the runway, in a remarkable demonstration of interservice coordination, a U.S. Air Force C-130 landed, hastily loaded the contents of the trucks into its cargo bay, and took off for Rhino. Though we couldn't say it at the time, Red Beach was on the coast of Pakistan.

Aviation ordnancemen transport laser-guided bomb unit-12 (GBU-12) and GPS-guided bomb unit-38 (GBU-38) to be placed in an F/A-18F Super Hornet aboard the Nimitz-class aircraft carrier USS Dwight D. Eisenhower (CVN 69) in the Arabian Sea

The flight deck of a U.S. aircraft carrier is a virtual ballet on a very dangerous stage. The various functions of the crew are defined by the colors they wear: red for ordnance handlers and crash/salvage teams, purple for those who fuel aircraft, green for catapult and arresting gear operators, blue for those who drive the tugs that move aircraft, brown for chock and chain handlers, and yellow for the officers and aircraft directors who choreograph the whole nonstop show. Visitors like me wear white. It's an extraordinary scene of activity. Every person has a vital task. One crusty old Navy chief put it this way: "The T.R. flight deck is the busiest American airport east of New York."

C-130 Aircraft have been an indispensable part of U.S. operations for more than three decades and were among the first on the ground in Afghanistan

The Rhino airfield had initially been secured by a U.S. Army/U.S. Air Force Special Operations "pathfinder" team. They parachuted in and set up beacons to guide in USAF C-130s with the Marines aboard. The whole undertaking was a remarkable and little reported example of just how good our military has become at "joint" operations.

By dawn, there was no sign that tons of munitions and cargo and hundreds of U.S. military personnel had staged across Pakistan's Red Beach. No U.S. ships were visible offshore. And at a remote airstrip in Afghanistan, the Marines were unloading another planeload of vitally needed supplies and personnel. Less than forty-eight hours after they arrived, the doctors I first met aboard the USS Bataan were treating more than twenty casualties inflicted by an errant U.S. bomb.

Enemy resistance began within twenty-four hours of the Marines' arrival. Though Taliban leaders were losing fighters at an astounding rate and watching critical cities fall to the Northern Alliance forces almost daily, they had stubbornly vowed to hold Kandahar. But on 6 December, just ten days after the first U.S. conventional forces arrived "in country," the city fell to a force of Pashtun fighters led by Hamid Karzai, the man who would become Afghanistan's first democratically elected president.

With the collapse of their defenses at Kandahar, most of the surviving Taliban and Al Qaeda fighters headed for the hills on the Afghan-Pakistan border. U.S. forces, bolstered by British, Australian, and French troops flowing into Rhino, Kabul, and new bases in the north, set up positions to cut off the enemy retreat toward the mountains. Over the next several weeks there were numerous harsh engagements with Taliban forces attempting to make a run for Pakistan. Though scores of Taliban and Al Qaeda fighters were killed, the Marines suffered no serious casualties. In fact, other than CIA officer Mike Spann, a former Marine captain, the Marine Corps would not lose a single man in combat in Afghanistan until April of 2004.

America's generals and admirals are often accused of preparing for the next war by refighting the last one. Whatever the validity of that charge in the past, it certainly wasn't the case in the opening phases of Operation Enduring Freedom. The campaign against Osama bin Laden's Al Qaeda terror network and the Taliban despots in Afghanistan was made up "on the fly" by soldiers, sailors, airmen, and Marines who rewrote military textbooks with one hand while they fought a new kind of war with the other.

From my firsthand observations for FOX News, it's evident that there were similarities to all other wars:

• massive numbers of ships, planes, men, materiel, and munitions;

• days and nights of back-breaking, sweat-drenched work being done by young Americans, thousands of miles from family and friends;

• countless hours of mind-numbing boredom punctuated by brief moments of stark terror; and

• loved ones at home, hoping and praying that a father, son, or brother—a mother, daughter, or sister—would return safely and soon.

But beyond these common connections to wars past, there was much about Operation Enduring Freedom that was different from anything our military had ever done before. Right from the start, this was a war for the record books:

• greatest number of aircraft hijacked in a single day: four;

• shortest time to build an international alliance to fight back: twenty-six days; and

• most journalists killed in a single week of war: eight.

And from 7 October 2001, when our counter-attack began, records continued to be set:

• The longest duration combat sorties in history: forty-eight straight hours (more than 14,000 miles by the B-2 bombers based at Whitman Air Force Base in Missouri).

• Longest close-air-support mission in aviation annals: eleven hours (by the U.S. Air Force 332nd Air Expeditionary Group).

• Highest number of close-air-support sorties flown in a single day in direct support of non-U.S. forces on the ground: seventy-one (by Navy, Marine, and Air Force F/A-18s, F-14s, F-15s, F-16s, and AV-8 Harriers).

• Deepest amphibious air assault ever conducted: 441 miles (by the 15th MEU).

• Longest resupply route to support a unit in hostile territory: 950 miles roundtrip (for the Marines at Forward Operating Base Rhino near Kandahar).

• Number of countries helping to win a war that do not want to be identified as "U.S. allies": seven.

That last entry in the record books is one reason why the war has been so challenging from the very start. U.S. commanders on scene, with whom I met, had to reconcile with the fact that the heads of state in the region didn't dare risk being seen as too close to the U.S.-led war effort. Afghanistan is a landlocked country, surrounded by nations where we had no U.S. military bases from which to launch offensive operations. This made the fight to finish the Taliban and Al Qaeda an extremely complex, very difficult, and very dangerous endeavor.

SIRKANKEL, AFGHANISTAN — Soldiers from the 1st Bn, 187th Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault), scan a ridgeline for enemy forces during Operation Anaconda

INTO THE HINDU KUSH

After the fall of Kandahar, Al Qaeda forces retreated to hideouts in and around the White Mountain region of Tora Bora in eastern Afghanistan along the border with Pakistan. There, they occupied a network of deep caves that had been used by the Mujahadeen during the war against the Soviets. When signals and human intelligence indicated that Osama bin Laden was likely hiding in the region, U.S. air strikes, guided by Americans accompanying Northern Alliance troops, pounded the entire region. But on 17 December, when the last of the cave and tunnel complex was overrun, there was no sign of bin Laden.

With the region now in the grip of a bitter Afghan winter, offensive operations ground to a near standstill. If, as some suspected, bin Laden had fled into Pakistan, he would be difficult to find. The border region has long been notoriously lawless and beyond the reach of the government in either Kabul or Islamabad.

Pakistan's president, Pervez Musharraf, already the target of multiple assassination attempts by Islamic radicals, had quietly permitted the use of Pakistani air space and territory for U.S. forces to transit into Afghanistan. But he was adamant that Western troops would not be allowed to conduct military operations inside his country.

Musharraf had reason for concern. Though he maintains tight control over Pakistan's nuclear weapons, officials inside his own government—particularly the Pakistani intelligence and security services—were known to be sympathetic to the Taliban and Al Qaeda. Powerful Islamic radical imams routinely preached that the U.S.-led attack on Afghanistan was tantamount to waging war against Islam itself. On 28 October 2001, Islamist radicals burst into a church in Bahawalpur and blazed away for ten minutes with AK-47s, slaughtering sixteen Christian worshippers. And when Wall Street Journal correspondent Daniel Pearl was kidnapped in Karachi in January of 2002, Musharraf's police and security services proved unable to prevent the reporter's gruesome videotaped murder the following month.

During the winter of 2001–2002, remnants of the Taliban and Al Qaeda capitalized on the Pakistani president's precarious hold on power and the extraordinary difficulties of feeding and caring for hundreds of thousands of Afghan refugees to reestablish themselves in the largely lawless border regions of the two countries. By February of 2002, the U.S. Central Command had devised a plan to hunt down and strangle the terrorists hiding in the hills. They called it Operation Anaconda. They timed it to start in March in the still-snow-covered foothills of the Hindu Kush.

U.S. Navy SEALS discover caches of munitions and weapons in the mountains of Afghanistan

OPERATION ANACONDA — U.S. soldiers pause to search for enemy movement during a patrol near Sirkankel, Afghanistan

0300 HOURS, 4 MARCH 2002

The sound of an approaching chopper echoed through the inky, pre-dawn blanketing of Takur Ghar, a snow-covered, ten-thousand-foot peak in the remote reaches of northern Afghanistan.

Standing in the back of the MH-47E Chinook helicopter, a SEAL reconnaissance team clung to the red nylon webbing covering the walls of the aircraft. It wasn't easy to stay on their feet as they checked their gear one last time.

Petty Officer Neal Roberts prepared to be the first to exit the aircraft, positioning himself on the chopper's rear ramp. The snow flashing beyond the black opening glistened in the moonlight.

U.S. Central Command and the CIA had been monitoring a large pocket of Al Qaeda and Taliban forces in the area for some time. Operation Anaconda was designed to wipe them out. Part of the plan called for positioning recon and surveillance teams on hilltops to provide intelligence and to call in supporting fire.

This chopper held one such team.

As the Chinook approached the designated landing zone (LZ) in a small saddle just below the summit of Takur Ghar, the pilot spotted a scattering of goat skins and human footprints in the snow. The mountaintop was already occupied.

He called to the team commander. "Looks like our insertion may be compromised, sir."

"Do we have enemy contact?"

"No, sir, but there are definitely signs of recent activity here."

The Special Operations pilot flared the helicopter to slow it down, coming to a hover over their intended landing spot.

"Roger," replied the mission commander over the Chinook's intercom. "Abort mission."

Before the pilot could acknowledge the command, a rocket-propelled grenade (RPG)struck the helicopter like a small meteor, blazing through the aluminum skin, throwing flame and shrapnel around the cargo bay, puncturing hydraulic and fuel lines, and wounding one man. As the pilot struggled to maintain control of the bird, the helicopter pitched sideways. This tossed a crewman off the tail ramp just as a machine gun began peppering the aircraft like invisible fingers of death stabbing holes in the thin exterior, looking for flesh inside.

Tethered to the aircraft with a safety harness, the rear crewman dangled only a few feet below the ramp. Reacting quickly, PO1 Neal Roberts dropped to his belly and reached out to help the crewman inside. But it was clear the helicopter wouldn't stay in the air for long. The pilot jerked back on the controls to try to gain some altitude in the thin mountain atmosphere. The action nearly stood the chopper on its tail. With no safety harness to stop him, Roberts slid off the tail ramp. His teammates watched him fall about ten feet to the snowy outcropping below.

As the Chinook peeled away from the mountain, the rest of the team watched in horror and frustration as Roberts came under heavy enemy fire. The last they saw of him, he was shooting back, attacking a superior force all alone.

CH-47 Chinook helicopter

Among the American Special Ops troops on board was Petty Officer Stephen Toboz. Born in Lock Haven, Pennsylvania, Stephen is the son of Glenda and Steve Toboz, a special education assistant and a retired state trooper.

After he graduated from Lock Haven High School with his brother Shawn, Stephen attended Lock Haven University and then enlisted in the Navy in 1991. After basic training, he went to the Navy's "A" School, where he studied electronics before traveling to Coronado, California, for BUD/S (basic underwater demolition/SEAL) training. This is the most demanding training in the U.S. armed forces, both mentally and physically. Trainees endure six months of rigorous training broken into three stages—basic conditioning, diving, and land warfare. Phase one also includes the infamous "hell week" in which candidates must endure five and a half days of continuous training, with a maximum of four hours sleep total. It is the ultimate test of a person's physical and mental motivation.

Stephen received his Trident in May 1993, officially marking his membership in one of the most elite Special Forces units in the world. From there, he reported to Naval Amphibious Base Little Creek in Norfolk, Virginia, and for the next five years served as a member of SEAL Team 8. In 1998 he was assigned to the Naval Special Warfare Development Group at Dam Neck, Virginia—the most select of all SEAL teams. That's why he was on a Chinook helicopter being shot at in the middle of the night over the hills of Afghanistan in March of 2002.

Back on Takur Gar, the wounded helicopter limped about half a mile and made an emergency landing. Stephen and his comrades charged into the snowy darkness and immediately set out to rescue their fellow SEAL.

During the ensuing gunfight, the badly outnumbered Americans fought valiantly. Out of the nearly two dozen U.S. soldiers who set out to rescue PO1 Roberts, six were killed. Among the eleven more who were wounded was Stephen Toboz.

Ordered to pull back by his team leader, Stephen was hit by a Taliban bullet that tore a fist-sized hole in his right calf. The projectile then spiraled down his leg, shattering the bones in his ankle and foot. Hours later when he was finally evacuated off the frozen hilltop, "Tobo" was still shooting back at those who had tried to kill him.

The U.S. doctors in Afghanistan saved his life. The doctors in Germany and back home in the U.S. tried to save his leg. But after multiple surgeries, Stephen figured he would get better faster without it. He told his doctors to amputate the leg below the knee.

Remarkably, that didn't end his career in the Navy. After being fitted with an ultramodern prosthetic limb, Stephen Toboz rejoined his team in Afghanistan. He says he did it because "Neal Roberts was my closest friend" and because "my parents taught me patriotism, duty, and determination."

Today Stephen Toboz is retired, but he still trains SEALs as a civilian instructor. Since he no longer wears a uniform, unless his young students hear it from others who know the story, they might never know that Stephen Toboz has a metal leg and foot or that he was awarded our nation's third highest award for valor—the Silver Star.

The President of the United States takes pleasure in presenting the Silver Star Medal to Aviation Boatswain's Mate 1st Class (Sea, Air, and Land) Stephen Toboz, United States Navy, for service as set forth in the following CITATION: For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity in action against the enemy while serving as a member of a special operations unit conducting combat operations against enemy forces in hostile territory from 3 to 4 March 2002. Petty Officer Toboz displayed extraordinary heroism, superb tactical performance, and inspiring perseverance as a member of a six-man team that flew back into an enemy stronghold atop a 10,000-foot mountain in order to rescue a captured teammate. Caught in automatic weapons crossfire upon insertion, PO1 Toboz immediately maneuvered against an enemy machine gun position, killing three enemies with accurate 5.56-millimeter fire. He continued to engage additional combatants until ordered to break contact by his team leader. While withdrawing, PO1 Toboz was hit by automatic weapons fire which shattered his lower leg ultimately resulting in amputation at a later date. Nonambulatory and nearly hypothermic, he pushed through exhaustion and intense pain to maneuver over one kilometer through icy and precipitous terrain, refusing morphine in order to preserve his security posture. PO1 Toboz' tactical expertise and courageous efforts significantly attrited the enemy fighters atop the mountain and contributed to their eventual defeat. By his outstanding display of immeasurable courage in the face of heavy enemy fire, untiring efforts, and selfless devotion to duty, PO1 Toboz reflected great credit upon himself and upheld the highest traditions of the United States Naval Service.

Navy SEAL Stephen Toboz back in Afghanistan

Sgt Jade Fry meets with local Afghan women in a voter registration center in Kandahar City. The presence of female soldiers displays America's resolve as a democracy to give equal rights to all its citizens

KARZAI'S COURAGE

In 2004, our FOX News team went back to Afghanistan to see how things had changed. Defying most of the critics in the so-called mainstream media, the people of what many considered to be an "impossible place to hold an election" had gone to the polls and chosen their first democratically elected leader.

For the first time in history, Afghan women went to the polls and cast ballots. They emerged triumphantly from the polling places with upraised purple index fingers or thumbs. In a live broadcast, I described it as the "indelible stain of democracy." Despite threats from Taliban propagandists and apologists that they would be killed for voting, people walked for miles—sometimes through minefields—just to cast their ballots.

The result was the selection of Hamid Karzai, a tall, ascetic man as the leader of their Loya Jirga, or legislative body.

Hamid Karzai

Hamid Karzai was living in Quetta, Pakistan, in 1999 when his father was gunned down in cold blood. The killers were agents of the Taliban government in Karzai's native Afghanistan. The killing was a warning to Karzai. He had been working to see the former king, Zahir Shah, reinstated in power.

The day his father was murdered was when Hamid Karzai dedicated his life to defeating the Taliban. And he didn't have to wait long to see his dream realized. Once the United States went to war in Afghanistan, Karzai emerged as a leader with the Northern Alliance forces, commanding a force of three thousand Pashtun fighters. With them, he helped wrest Kandahar from the Taliban and became the chairman of the transitional administration a month later when he met with other Afghan leaders in Bonn, Germany. Six months later, a council of tribal, civic, and religious leaders voted him the interim president of the country.

The road ahead promised to be rocky. He had his hands full trying to rebuild his nation, defeat the remnants of the Taliban, and dodge multiple assassination attempts. Two years later he won 55 percent of the vote for president in the first national election in Afghanistan's history. And all of this because American soldiers, sailors, airmen, and Marines were willing to fight back against those who had started a Jihad against us.