LIBERATION LOSES ITS LUSTER

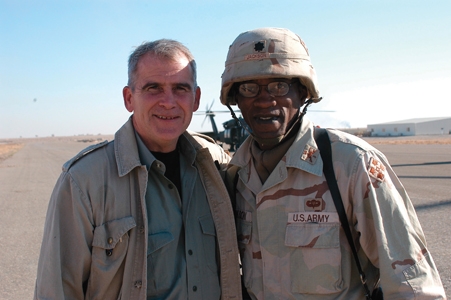

With LTC Pepper Jackson in Bayji, Iraq

EASTER MONDAY, 21 April 2003

We "celebrated" the resurrection on the road in a Humvee. Just before dark on Easter Sunday we arrived at the outskirts of Tikrit with LTC Larry "Pepper" Jackson's 3rd Bn of the 66th Armored Regiment, part of the 4th ID out of Fort Hood, Texas. When his armored column halted for the night, Griff and I rode forward with SFC Terrigino, the senior NCO in the battalion's reconnaissance platoon, as they scouted the route into Saddam's hometown. The only evidence that this had once been the dictator's stronghold were the burned-out hulks of Iraqi tanks, trucks, and armored vehicles on the shoulders of the road.

One of Saddam's many palaces in Tikrit became the 4th ID headquarters

Early on Monday we accompanied LTC Jackson into the city and went directly to the deposed despot's opulent palace perched on a bluff overlooking the Tigris River. This was the third of Saddam's many palaces I'd been in at that point, but it was the only one not damaged by coalition bombs. MG Ray Odierno, the 4th ID commanding general, had decided to use it as his headquarters.

Like all of Saddam's residences, this one overlooked some of the most beautiful scenery in all of Iraq. It was encircled by irrigated orchards of fig and eucalyptus trees. An enormous swimming pool graced the south side of the ornate, three-story building. Carefully manicured gardens were terraced into the hillside to the east and south. On the west side, there was a six-car garage, complete with an armored Mercedes limousine.

Yet just out of sight in the surrounding neighborhood, there were thousands of homes without electricity, running water, or sewage systems. Saddam had to have been totally oblivious to the suffering of his people as he turned the country's oil profits into his own personal fortune—or he just didn't care.

Not surprisingly, all of the Iraqi dictator's staff had fled as the Marines of Task Force Tripoli closed in on Tikrit a week earlier. In the days after 4th ID replaced the Marines, Army patrols had managed to capture and detain several of the Iraqi dictator's relatives and high-ranking Baath Party officials before they could flee to Syria. Before I departed the castle, COL Don Campbell, the commander of the 1st Bn Combat Team, told FOX News: "Our missions are to find Saddam, his two sons, and his henchmen and establish a civil government here in this province . . . and we're going to do just that."

As it turned out, the first parts of the mission would be easier to accomplish than the last.

FRIDAY, 25 APRIL

We moved with Pepper Jackson's 3rd Bn, 66th Armor, to Bayji, out in the desert northwest of Tikrit. Though U.S. Special Operators had infiltrated the city during the early phase of the campaign, Jackson's troops were the first to take up positions in the area. His soldiers found the local oil refinery, pipelines, and pumping facilities intact and immediately secured them. But in the desert just outside the city, they also found one of the largest ordnance storage facilities in Iraq. They quickly determined that it was completely unsecured.

Saddam had constructed the ammunition depot and nearby railroad switching yards during the 1980–88 Iran-Iraq war because the site was beyond the range of Iran's missiles and air force. The Iraqi army unit responsible for securing the place had simply walked away from their guard posts when Baghdad fell on 9 April. With no one there to stop them, local Iraqis removed nearly twenty kilometers of chain-link perimeter fence and began systematically looting the hundreds of bunkers and warehouses.

Saddam stored 300 million tons of ordnance at the Bayji munitions depot

The depot was far too large to be secured by a single battalion, so Jackson ordered his companies to outpost the facility and set ambushes on the avenues of approach to the ammo dump. His instructions were, "Do what you have to do to keep anyone from getting into this place, because God help us if the fedayeen get their hands on this stuff." Every night for the rest of the time we were with that unit, at least one of Jackson's units would catch Iraqis or fedayeen trying to steal truckloads of ordnance.

The morning after one such "event" I filed this report:

When we arrive, the platoon commander who triggered the ambush is reviewing with his soldiers what happened. The bodies of fourteen men, nearly all dressed in black, are lying on or near a rutted dirt road that enters the ammo dump from the east. According to the battalion S-2, who has collected identity documents from the bodies, only two of the dead are Iraqi. Of the remaining twelve, four are Jordanian, three are Syrian, two are Egyptian, one is a Saudi, and the other two are Lebanese.

The foreigners and their two Iraqi guides, all armed with AK-47s, had disembarked from two pickup trucks about two hundred meters from the nearest ammunition bunkers and walked straight up the road into the killing zone of the night-vision-equipped platoon-sized ambush. The carnage was completely one-sided. There were no American casualties.

U.S. Army engineers and ordnance specialists inspected the depot over the course of several days, with us in tow. What they found were more than five hundred ordnance bunkers and revetments and ninety-five steel structures filled to the top with every conceivable type of ammunition and explosive from around the globe.

Much of the ordnance was in very good shape. Some of it—including Jordanian artillery rounds, Italian land mines, and Saudi small-arms ammunition—was nearly new. In one shed, several hundred green wooden boxes were labeled "Ministry of Procurement, Amman, Jordan," and had shipping tags with delivery dates in January 2003. Several steel buildings contained hundreds of cases of man-portable, shoulder-launched surface-to-air missiles: SA-7s, SA-14s, and SA-16s.

The unguarded anti-aircraft missiles and the tens of thousands of land mines and RPGs created the greatest anxiety among the specialists trying to inventory the site. These weapons can bring down a military helicopter or commercial jet. The mines and RPGs can take out a Bradley fighting vehicle and even an M-1 tank. Many of the surface-to-air missile and RPG cases had been broken open and emptied.

I asked one of the experts what they planned to do with all the ordnance. "I don't know," he responded. "We haven't got enough TNT, Det-Cord, and blasting caps to blow all this. Worse yet, there are probably seventy-five to one hundred sites just like this one elsewhere around the country."

When I left Iraq on the 26th of April, people were still cheering for American troops

SATURDAY, 26 APRIL 2003

On the 25th, twenty-six-year-old Army 1LT Osbaldo Orozco became the first Fort Hood soldier to die in Iraq when his Humvee flipped over while on a combat patrol. That same day, Tarik Aziz—Saddam's former deputy prime minister and the only Christian in the Baath Party inner circle—was captured. As in so many other cases, he was found after a tip from an Iraqi civilian.

Early on the morning of 26 April, the FOX News foreign desk called on my satellite phone and told us that we could head home. Though it had only been two weeks since the fall of Baghdad, it was already becoming clear that the nature of the campaign in Iraq was changing. Conducting "pacification" and civil affairs operations were becoming increasingly dangerous as foreign Jihadists continued to flood into the country.

Before heading to Kuwait for a flight home, we stopped in Tikrit to interview MG Ray Odierno, commander of the 4th ID. His parting words aptly summarized the situation for U.S. troops two weeks after the fall of Baghdad:

"In many respects this is tougher than beating Saddam's army. We really don't know who the enemy is. He dresses like, looks like, and lives among the civilian population. We are going to need their help if we're going to defeat them—and that means we have to convince the Iraqi people that we're on their side as liberators, not as conquerors. That could prove to be a very tough task."

—MG Ray Odierno

Events over the next several months would prove General Odierno to be right on the mark. About the only point he might have added was how hard it would become to keep America's people and political leaders behind the troops.

South of Baghdad, a soldier searches an Iraqi civilian at a security checkpoint

MISSTEPS AND THE RISE OF THE INSURGENCY

As Griff and I journeyed home, the USS Abraham Lincoln was headed there too. After ten months of combat operations, including Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan and Operation Iraqi Freedom in Iraq, the aircraft carrier and its crew of 5,500 had traveled over 100,000 miles in support of the War on Terror.

Recognizing the skill and dedication required for such a commitment, President Bush decided to say "well done"—not only to the sailors on the Lincoln but to all of his troops. A former pilot, the President flew aboard in the cockpit of a Navy S-3B Viking, taking the controls for part of the trip. By landing on a moving carrier—an extraordinarily difficult feat—he paid the crew on board the Lincoln the ultimate compliment: he put his life in their hands.

President Bush with the flight deck crew on the USS Abraham Lincoln

Then, the commander-in-chief made a dramatic speech commending both the crew and all the troops who had helped end Saddam Hussein's rein of terror.

"The transition from dictatorship to democracy will take time, but it is worth every effort. Our coalition will stay until our work is done and then we will leave and we will leave behind a free Iraq."

—President Bush

Unfortunately, the media fixated not on the words of the president's speech but on a banner behind him that read "Mission Accomplished." It had been hung by the crew of "Honest Abe" who were glad to be coming home. The media seized on the image of the president in a flight suit standing before the banner and pilloried him. It was a major public relations gaffe that gave adversaries of the administration new ammunition, and it could have been prevented by the president's staff. But this misstep was followed by a far more grievous error.

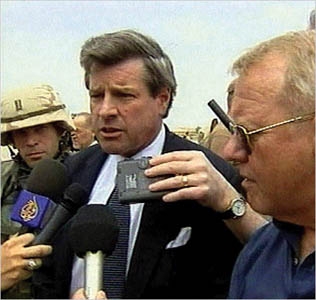

Five days after what the potentates of the press derisively called his "Mission Accomplished Speech," President Bush appointed L. Paul "Jerry" Bremer as administrator for the Coalition Provisional Authority. The CPA had been created shortly after the capture of Baghdad to oversee the reconstruction of Iraq and provide leadership for reconstituting a new civil government.

L. Paul Bremer arrives in Iraq

Though accepting the assignment in Baghdad placed him at considerable risk, Bremer's appointment was controversial from the start. The person he replaced as CPA administrator, Jay Garner, a retired U.S. Army lieutenant general, had been criticized in the U.S. media for moving too slowly on reconstruction and "de-Baathification"—getting rid of former regime loyalists. But even before Jerry Bremer arrived, he was denounced by the press for being "too political" and "too close to the Bush administration."

In fact, Jerry Bremer came to the CPA with better credentials for combating terrorism than almost anyone President Bush could have chosen. In 1986, when I left my post on the National Security Council staff as the U.S. government's coordinator for counter-terrorism, Jerry Bremer was my replacement. He had a redefined mission and title: Ambassador-at-large for Counterterrorism. He had also served as chairman of the National Commission on Terrorism. After the 9-11 attack he cochaired a task force that drew up plans for creating the new Department of Homeland Security.

Bremer's instructions from the White House and the Pentagon included requirements for the CPA to "actively oppose Saddam Hussein's old enforcers . . . and eliminate the remnants of Saddam's regime." This guidance hobbled reconstruction by preventing the interim government from using talented administrators and technocrats who had joined the Baath Party simply to keep their civil service jobs under Saddam.

But the greatest damage to the prospect for peace in Iraq was the failure to immediately recall the remnants of the Iraqi military. Bremer's directive of 23 May 2003 effectively dissolved the entire Iraqi military system. The order told nearly 500,000 trained and armed young men that they were not part of the "New Iraq." Without options for legitimate employment, thousands of them became the "hired guns" for sectarian militias and Al Qaeda.

Bremer's rebuttal, in a FOX News interview, that "there was no Iraqi army to disband. The Iraqi army basically self-demobilized" was true, as far as it went. But it ignored what he might have done about it, as well as the lessons of history.

BAGHDAD, 18 April 2003 — Lt. Gen. William Wallace tells his soldiers to stay vigilant as Operation Iraqi Freedom transitions into a peacekeeping and humanitarian stage. "Don't let your guard down," Wallace said. "Show the people of this country the proper respect, but be careful. There's still a bunch of knuckleheads running around." He went on to praise the troops for giving "back to the Iraqi people the society and culture that is rightfully theirs."

In May of 1945 when Germany surrendered, GEN Dwight Eisenhower issued orders to arrest all Nazi Party members. He instructed all German military personnel to return to their barracks with their weapons. In the zones occupied by U.S., British, and French forces, military police collected the Mausers and panzerfausts and issued shovels and wheelbarrows. The defeated army was put to work cleaning up the destruction. They were fed, clothed, and paid a modest sum by the U.S. Army, and they started rebuilding their country. George Patton, the military governor of Bavaria, went so far as to grant amnesty to low-level Nazi functionaries just to get public works—water, sewage, electricity, and the civil police—functioning again.

The same could have been tried in Iraq. In May of 2003, the Coalition effectively controlled all information being disseminated to the Iraqi people—print, broadcast, and many of the leading clerics. It would have been simple for the CPA to put out the word that every Iraqi soldier who returned to his barracks with his weapon would receive one hundred dollars at the end of thirty days.

It was never tried. Instead of becoming a work force rebuilding Iraq, many from the defeated Iraqi army became bomb builders, terrorists, and new recruits for Shiite and Sunni warlords. It was an unmitigated disaster.

By July of 2003, armed bands were operating throughout the countryside and in nearly all of Iraq's major cities. In Baghdad, Washington, and European capitals, critics of the Bush administration cited the "rise of an insurgency." The words "quagmire' and "Vietnam" appeared with increasing regularity in the press.

In reality, the parallels between Iraq and Vietnam are practically nonexistent—on the battlefield. But in the press and politics, it didn't matter that there were few similarities, except that ground combat remains a brutal, vicious experience for all who engage in it.

In Vietnam, U.S. troops faced nearly a quarter of a million conscripted but well-trained, disciplined, and equipped North Vietnamese Army (NVA) regulars and upwards of 100,000 highly organized Viet Cong (VC) insurgents on a constant basis from 1966 onward. Both the NVA and the VC "irregulars" were well indoctrinated in communist ideology; received direct aid from the Soviet Union, Communist China, and the Warsaw Pact; and benefited from logistics and politico-military support networks in neighboring countries. During major campaigns against U.S. and South Vietnamese forces—of which there were many each year—both the NVA and the VC responded to centralized command and control directed by authorities in Hanoi. None of that has been true in Iraq.

Since the summer of 2003 in the land between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, enemy combatants have been a combination of disparate Sunni Jihadi-terrorists, disenfranchised Baathists, Shiite militias aligned with Iran, fanatical foreign Wahhabi-subsidized Mujahadeen linked to Al Qaeda, Muslim Brotherhood-supported radicals, and well-armed, hyper-violent criminal gangs, often with tribal connections that are stronger than any ideological, religious, or political affiliations. Though many Jihadists receive indoctrination, munitions, and refuge from a network of mosques and sectarian Islamic groups, centralized command, control, and logistics support is virtually nonexistent.

Operating in small independent "cells" instead of organized, disciplined military units, the enemy in Mesopotamia has no ability to mount any kind of protracted offensive against U.S. or even lightly armed Iraqi government forces. Increasingly dependent on improvised explosive devices (IEDs) and suicide-bomb attacks to inflict casualties, the opposition in Iraq is more "anarchy" than "insurgency."

The second great myth about the campaign in Iraq is the casualty rate. This is always the most difficult aspect of any war to address, because all comparisons seem cynical. For those of us who have held dying soldiers, sailors, airmen, Guardsmen, or Marines in our arms—and the families of those killed—this is particularly painful. Yet, the casualty rate is one of the oft-cited reasons for why we were "forced" to get out of Vietnam, and why we are once again being urged by the press and politicians to "end the bloodshed" in Iraq. While no one should ever claim "my war was tougher than your war," here's a reality check:

• Over the course of the entire Vietnam War, the "average" rate at which Americans died as a consequence of armed combat was about fifteen per day. In 1968–69, when my brother and I served as rifle platoon and infantry company commanders—he in the Army and I in the Marines—thirty-nine Americans died every day in the war zone. In Iraq, the mortality rate for U.S. troops due to enemy action is less than two per day.

• During the 1968 "Tet Offensive" in Vietnam, there were more than 2,100 U.S. casualties per week. In Iraq, the U.S. casualty rate from all causes has never exceeded 490 troops in a month.

• As of December 2007, after more than fifty-seven months of combat, fewer than 4,000 young Americans have been killed by enemy action in Iraq. That's roughly the same number killed at Iwo Jima during the first ten days of fighting against the Japanese.

Every life lost in war is precious, and every loss is grievous for their friends and families. Unfortunately, our media seems intent on using every one of those killed to make the point that they died for nothing. It's a technique that was perfected during Vietnam. Those who shape American public opinion apparently intend to make it true for Iraq.

On 27 February 1968, after a month of brutal fighting and daily images of U.S. casualties on American television, Walter Cronkite, then the host of the CBS Evening News, proclaimed that the Tet Offensive was proof that the Vietnam War was "no longer winnable." Four weeks later, Lyndon Johnson told the nation that "I shall not seek, and I will not accept the nomination of my party for another term as your President." It didn't matter that Tet had been a decisive victory for the U.S. and South Vietnamese.

The war in Vietnam wasn't lost during "Tet '68," no matter what Walter Cronkite said. Rather, it was lost in the pages of America's newspapers, on our televisions, our college campuses—and eventually in the corridors of power in Washington.

By mid-2003 we had reason to pray that the campaign in Iraq wouldn't be lost the same way.

"The thugs we're fighting in Iraq aren't, for the most part, organized soldiers. They're mostly criminals and cowards. They talk real tough when they're strutting around on television with their guns and their buddies behind them. But kick in their door in the middle of the night and stick a gun in their face, and they cry like little girls and wet themselves."

— An unnamed Special Operations soldier in Iraq, 2004

Smoke billows from a building hit with a TOW missile launched by soldiers of the Army's 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault) on 22 July 2003 in Mosul, Iraq. Saddam Hussein's sons Qusay and Uday were killed in the battle as they resisted efforts by coalition forces to apprehend and detain them.

DYING TO KILL US

Daytime summer temperatures in the "land between the rivers" average more than 105 degrees. By July 2003 the anti-war rhetoric in Washington and European capitals was just as hot. Coalition efforts to jump-start reconstruction were slowly getting underway but few of the "good news" stories made it to air or on the front pages. Even when Saddam Hussein's vicious sons, Uday and Qusay, were killed in a gunfight with U.S. troops in Mosul, the media found reason for criticism.

Uday, the elder sibling, had been responsible for recruiting foreigners to fight for his father's regime. Qusay had headed the Amn Al Khass, Iraq's internal intelligence and security force. Both brothers had a well-deserved reputation for extraordinary cruelty and had been accused of torture, numerous rapes, and scores of murders.

On 21 July, an Iraqi civilian tipped off a young U.S. Army sergeant in Mosul that the deposed dictator's sons were hiding at a particular address in the city's Al Falah district. In less than twenty-four hours soldiers from the 101st Airborne, commanded by MG David Petraeus, and Special Operators from Task Force 20 had confirmed the information and cordoned off the neighborhood.

To prevent civilian casualties the troops evacuated the surrounding homes and businesses and urged the fugitives to surrender. Instead of doing so, they opened fire on the U.S. troops surrounding the building. In the subsequent assault both brothers, their sole bodyguard, and Qusay's teenage son were killed. Five U.S. troops were wounded.

The success of this operation was quickly obscured by protests in the media that U.S. troops had used "excessive force" and complaints that Saddam's sons should have been "taken alive for their intelligence value" and then "tried for their crimes."

The remains of a suicide truck bomb in Baghdad

With the summer heat in Iraq came a wave of "suicide bombers"—individuals carrying explosives on their bodies—or driving vehicles laden with ordnance and intent on dying in the Jihad. On 19 August a terrorist driving a Russian-made flatbed truck pulled up next to the Canal Hotel, headquarters for the UN mission in downtown Baghdad. Beneath a tarpaulin on the truck were a five-hundred-pound bomb and dozens of mortar and artillery rounds, land mines, grenades, and plastic explosives—all readily available throughout Iraq. Unchallenged, the driver parked the lethal load beside a brick wall surrounding the hotel and detonated his cargo. The blast killed twenty-five people, including the UN special representative to Iraq, Sergio Vieira de Mello, and wounded more than one hundred others. Scenes of the carnage, some of it videotaped as the bomb exploded, were broadcast around the world almost instantly.

Over the course of the next several months there were scores of such suicide attacks that killed hundreds and maimed thousands of noncombatants. On radical Islamic Web sites the perpetrators were called "martyrs." President Bush described them as "the enemies of civilization." By the time our FOX News War Stories team—cameraman Griff Jenkins, senior producer Pamela Browne, and I—returned to Bayji with Pepper Jackson's 3rd Bn, 66th Armor, in October 2003, suicide bombers and IEDs were the number-one killers of American troops and Iraqi civilians.

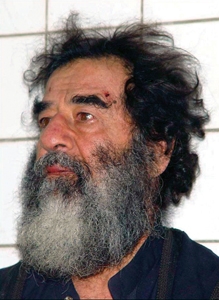

Jackson's troops and the rest of the 4th ID didn't let the increasing risk from suicide bombers and IEDs deter them from continuing their hunt for Saddam and his cronies. And on 13 December their patience and perseverance were rewarded.

American soldiers trapped him like a cornered rat hiding in a hole. And when he was caught, Saddam Hussein—the blustering, bloody tyrant who asked others to die for him—didn't even try to defend himself with the weapons at his disposal. Just days before the capture, I interviewed MG Ray Odierno, the 4th ID's commander. He assured me that his troops were going to find Saddam near Tikrit. They did.

Saddam was responsible for two horrific wars and the deaths of hundreds of thousands. His record was replete with the kind of atrocities that brought the United States into two world wars, a bloody campaign in Korea, and the war I fought in—Vietnam. He had raped, tortured, robbed, starved, and murdered his own people. He acquired and used weapons of mass destruction against his neighbors and countrymen. He had attempted to assassinate an American president and trained and supported Hamas, Islamic Jihad, Hezbollah, and Muslim Brotherhood terrorists who killed Americans.

The image of Saddam as a filthy, decrepit, coward captured—not killed—by an American soldier was a powerful message to repressed people all over the globe that this is the way brutal despots go. Placing him on trial before the people of Iraq, who subsequently sent him to the hangman's gallows, sent a clear signal to totalitarians—be they in Damascus, Tehran, Pyongyang, or Havana—that they are accountable to the people they have tortured.

Though tens of thousands of Iraqis celebrated Saddam's capture, the jubilation was less than universal. Critics in the European press decried the "humiliation" of videotaping "a former head of state" being examined by a U.S. military medical officer. The "mainstream media" in America speculated that the capture was "timed to improve Bush's poll numbers" and opined that Saddam would be tortured. Madeline Albright, who had been secretary of state in the Clinton administration, asked on FOX News: "Do you suppose that the Bush administration has Osama bin Laden hidden somewhere and will bring him out before the election?"

The surreal reaction to Saddam's capture was revealing. Media elites could have focused on the extraordinary courage, tenacity, and discipline of U.S. and coalition troops who had defeated Saddam's army and then captured the "Butcher of Baghdad." Instead, many of the most powerful shapers of public opinion persisted in denigrating the young Americans serving far from home in harm's way and insisting that they were engaged in a fight that couldn't be won. None of this was missed by those who were intent on spreading their Jihad and driving "the infidels" from what they called "the lands of the Prophet."

Despite pervasively nega-tive press coverage, most of the U.S. troops I have covered simply refuse to be disheartened. But there is also no doubt in my mind that it has made their task much more difficult.

An Iraqi man takes his aggression out on one of the many large public murals of Saddam Hussein— he is hitting the mural with his shoe, which in Muslim culture is akin to spitting at someone