2

Sweet: The Taste of Innocence

Featuring: GLUCOSE, CUTENESS, HELLO KITTY, SITCOMS, MURDER, SHE WROTE, BEANIE BABIES, “CARELESS WHISPER,” AND, ABOVE ALL ELSE, KINDNESS

They surfeited with honey and began

To loathe the taste of sweetness, whereof a little

More than a little is by much too much.

—SHAKESPEARE, KING HENRY IV, PART I

There’s a good argument to be made for taking candy from a baby: babies shouldn’t be eating candy. But try explaining that to the bawling infant. She was enjoying that lollipop before you wrenched it out of her sticky hands, and now her mother is giving you a look. The fact is that sugar is the taste of safety. We evolved to know that if something tasted sweet, we could probably eat it without dying (or at least, not dying immediately). Sweet is the one taste we all like from birth. The brain needs glucose, and it points the tongue in that direction. Our ancestors who lacked this tongue-brain wiring didn’t get around to reproduction.

Sweet is the one taste we all like from birth.

When you equate sugar and safety, the obesity epidemic has a new underlying theme: these truly are comfort foods. And like the spoiled kid with a menagerie of stuffed animals piled on his bed, we’ve unconsciously decided that if a bit of sugar identifies food that’s safe to eat, a few scoops more signal food that’s even better. So we add sugar to bread, spaghetti sauce, and sliced cheese, turning every meal into dessert. The irony is that the high doses of sugar we ingest as part of the Western diet are likely toxic in their own right, meaning this flight to more and more safety is putting us in peril. Too much of a good thing can be wonderful, as Mae West said, which in this context makes it entirely appropriate that there’s a Quebecois variation on the Twinkie named for the burlesque star.

But there are signs that our appetite for sugar knows some bounds. Soft-drink sales in the United States have been dropping since the late 1990s, with the amount of full-sugar soda consumed by the average adult dropping 25 percent—despite the fact that no fewer than forty flavors of Mountain Dew were introduced in that time. To not even slow your shopping cart’s roll as you pass the Mountain Dew Game Fuel Electrifying Cherry display? Well, that suggests a real change in the American consumer’s tastes. Still, this is a gradual rollback, and sweetness shows no signs of giving up its spot as the most popular of the five tastes.

Sweetness as safety carries over into the broader culture. There is always an audience for safe works of art—the plays, movies, and shows that end with a wedding, a sunset, or at the very least a group hug. Children’s entertainment is understandably cuddly, but it’s quite possible to continue consuming age-appropriate sweetness throughout your lifetime. Sitcoms that reinforce the nuclear family, animated films made with gentle pop-culture references for parents and big-eyed characters for the kids, coloring books for adults. Even murder mysteries—books centered around the violent taking of another human’s life, the least safe event imaginable—have a subgenre called the cozy.

To use another word, sweetness is cute. In 2001, The Onion published an article with the headline “Area Woman Judges Everything By Whether It’s Cute.” The subject of the satirical article “uses the word ‘cute’ more than 150 times a day, applying it to everything from such traditionally cute items as infants and stuffed animals to such nontraditional items as board games, soft-drink bottles, and art.”

In 2014, “while working on a research paper exploring female consumers’ brand-driven retail decision making,” three marketing researchers felt compelled to point out that the word “cute” kept recurring in their interviews. At first it passed unnoticed because the researchers were male and “tended to use the word when referring to a baby, or a puppy.” The women they interviewed, however, “used the word to describe products, brands, people, stores, and even regarded it as a state of being.”

As usual, there was more than a grain of truth in The Onion’s story, and it was more than a grain of cultural sugar. The female’s traditional role as primary caregiver is the classic evolutionary explanation for why women are primed to appreciate cuteness.

Sweet culture is uncomplicated, accessible to all, lighthearted, gentle, and—for all these reasons—popular. It’s often what we get when we don’t make a choice. It’s sometimes where we go when we’re confronted with difficult circumstances. It’s usually at the heart of otherwise inexplicable fads. And it should never be written off as dumb. Too much sweetness is unavoidable in modern life, but too little—or none at all—makes life barely worth living. Group hug!

Kawaii: The Sweet Society

There is no nation on Earth more saturated in cultural sugar than Japan. There, sweet culture is the universally beloved kawaii style.

According to the scholar Sharon Kinsella, by the early 1990s “kawaii” was “the most widely used, widely loved, habitual word in modern living Japanese.” And what, exactly, does the word mean? “Aside from pastel colors, a compositional roundness, the size of the eyes, a large head and the short distance from nose to forehead, quite often it is things or people that are not trying to be cute,” writes Manami Okazaki in her 2013 book on the phenomenon. So it’s a sort of authentic cuteness, the attribute babies and kittens come by naturally and that makes Hello Kitty worth a billion dollars a year.

Some scholars trace kawaii back to 1914, when the illustrator Yumeji Takehisa opened a Tokyo shop geared exclusively to schoolgirls. Marketing to this demographic was virtually unheard of, which makes his first customer the patient zero of our era’s obsession with youth culture. He sold illustrated books, prints, and dolls that featured cute patterns of things like mushrooms and umbrellas, and he described the aesthetic he was aiming for as “kawaii.”

The kawaii culture began in earnest in the early 1970s as a very specific handwriting style embraced mainly by teenage girls using mechanical pencils. The English penmanship equivalent would be dotting your i’s with hearts, but this was exponentially more stylized—rounded letters, kittens frolicking between words, hearts and the English word “love” randomly inserted into text. This underground fad—think of them as the ancestors of emojis—wasn’t particularly legible and was banned in some schools, which of course had the effect of making it more popular.

Around the same time, slang that sounded like baby talk began to spread, and with it a penchant for acting like children. Hello Kitty and scores of similar round and large-eyed characters were introduced and plastered on everything from rice cookers to credit cards.

Sweet foods were a key part of kawaii culture, and as in English, the word for sweet can refer to both food and people. In Japan, ice cream was a growth industry throughout the 1980s, despite the population’s high genetic likelihood of lactose intolerance.

So why kawaii? Kinsella posits that the cold industrial economy needed to soften its edges. “Cuteness loaned personality and a subjective presence to otherwise meaningless—and often literally useless—consumer goods and in this way made them much more attractive to potential buyers,” she writes. That economic need twinned nicely with the country’s culture of respect for inanimate objects, a deference central to the Shinto faith and perhaps best seen in the annual Festival of Broken Needles, during which seamstresses ceremoniously insert their used sewing needles into a block of tofu. (Or more popularly in The Life-Changing Magic of Tidying Up, in which Marie Kondo encourages her disciples to thank their dirty socks after a hard day of being trod upon.)

And then there’s the fact of Japan’s aging population. In 2014, the Land of the Rising Sun had the distinction of being the world’s fastest-aging nation, with more than a quarter of its population over the age of sixty-five. It’s reminiscent of the P. D. James dystopian novel Children of Men, in which a global fertility crisis ends childbirth and humans treat their pets as children. With a relative lack of real small people, there’s some logic in adults acting like kids and making mundane consumer products look like toys.

More pointedly, the artist Takashi Murakami has argued that kawaii is indicative of “the tragic apocalyptic paradise that is Japan today,” a cultural reaction to Japan’s childlike relationship to the United States since the end of World War II. He made specific reference to this in the 2005 exhibition he curated at the Japan Society in New York, cleverly titled “Little Boy: The Arts of Japan’s Exploding Subculture.” In addition to referencing the name of the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima, Murakami points out that his country’s artists depicted the most horrible weapon ever created as a dinosaur. Superflat is the name he gives to all of this 2-D culture, in the sense that all of the country’s complex fears and anxieties are flattened into cartoons.

In the extremes of kawaii, these anxieties come into raised relief. Kimo kawa is one form of this, “kimo” being an abbreviation of the word “creepy” and “kawa” a short form of “kawaii.”

The Chinese artist Lu Yang hit both of these marks with “Kimo Kawa Cancer Baby,” which exhibited in Shanghai in 2014 and consisted of brightly colored sculptures of googly-eyed tumors chewing on human organs, animations of Cancer Babies, and a looping, upbeat song with the refrain “We are happy cancer cells.” The artist’s intention, she told the Lancet, was to negotiate the irony of the natural world. “Some people hate it because they hate cancer, and they think I’m using disease and death to make fun, but some people think we should face the reality and not avoid it.”

The artwork, given kawaii’s emergence as a response to grim realities, is less an ironic twist than a natural extension. The unnatural extension is guro kawaii, or the grotesque cute. Gloomy Bear, a life-sized homicidal pink bear generally depicted spattered with blood, is perhaps the best example of guro kawaii. Introduced in the year 2000 by the Osaka artist Mori Chack, the origin story of Gloomy has him adopted as a cub who, as he is an actual bear, eventually attacks his human owner. Chack has said the idea came after he saw a news report about a bear attack and decided to inject “a sense of that terror in that cuteness.”

Though this strand of kawaii culture is often depicted as shocking—“This isn’t kawaii. It’s disturbing.”—is a typical blog reaction—in the case of Gloomy Bear, it’s really just taking the kawaii aesthetic and applying it to reality.

“Some may think, ‘Drawing pictures of bears attacking children is cruel,’” Chack writes on his website. “Has anyone noticed that, in my work, I have embedded my opinion that humans are the most brutal creatures on earth?” The observation is an extension of Murakami’s theory. In these mutations of kawaii, we see sweetness blended with sour thrills, salty darkness, and bitter art. And we see how a balanced and sophisticated cultural diet can be built on a sticky-sweet base. Kawaii starts from innocence but encompasses all aspects of life.

In Japan, every town and city has at least one yuru-kyara, a word that loosely translates as “mascot” but has more than a trace of animism about it. They are all varying degrees of kawaii, and in a very real way, these creatures are the places they represent. When an earthquake struck the city of Kumamoto in April of 2016, killing tens and injuring hundreds, there was a social-media outpouring of concern for Kumamon, the region’s rosy-cheeked bear yuru-kyara. The mascot’s eventual reappearance, as Neil Steinberg describes it, was pure catharsis.

“Three weeks after the April 14 earthquake, Kumamon visited the convention hall of the hard-hit town of Mashiki, where residents were still sleeping in their cars for protection as 1,200 tremors continued to rumble across the area. The visit was reported on TV and in the papers as news, as if a long-sought survivor had stumbled out of the wreckage alive. The children, many of whom had lost their homes in the earthquake, flocked around him, squealing, hugging, taking pictures. Their friend had returned.”

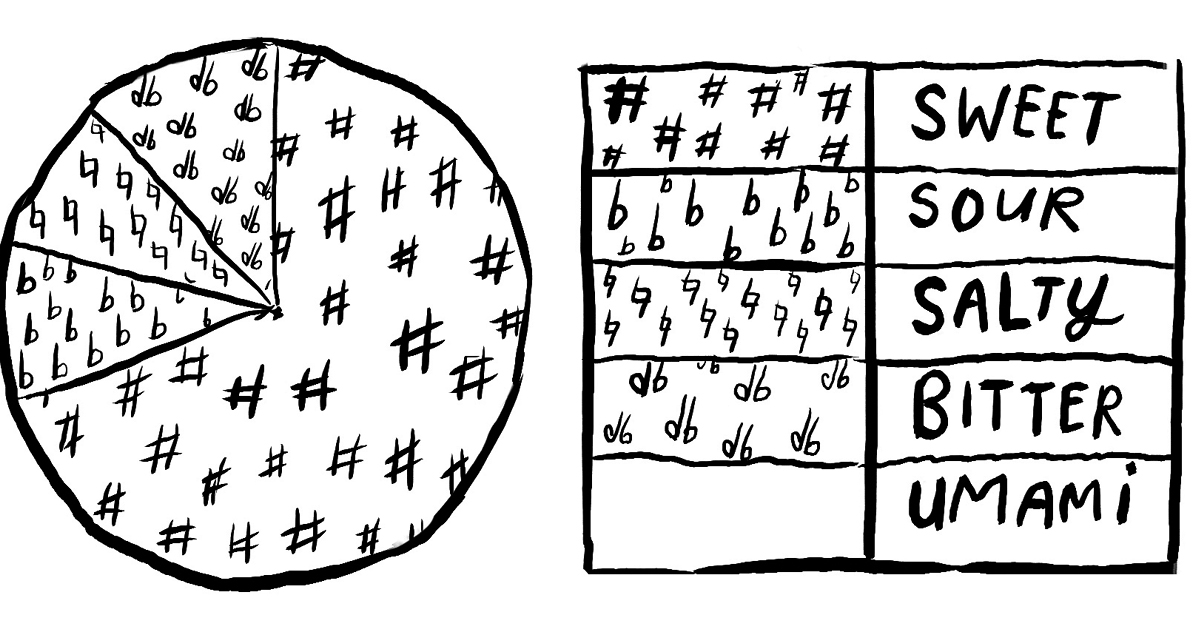

TASTING NOTE: COLDPLAY

Sweet: 70 percent

Sour: 10 percent

Salty: 10 percent

Bitter: 10 percent

Umami: 0 percent

When the world first heard Coldplay announce they were all yellow in the year 2000, the British band sounded a lot like mid-1990s Radiohead. By that point Radiohead was off exploring new sonic dimensions, leaving Coldplay to double down on ballads. Soon the emotional piano pop of Chris Martin and his bandmates was everywhere, and in the parlance of those times, you were either with Coldplay or against them. Their music is sentimental but stadium-sized, a less-specific U2, designed to make you cry without knowing why. They have sold millions of albums, yet hating Coldplay is as prevalent a pop-cultural opinion as you can get. Why? Because we expect a rock band to be thrillingly sour or defiantly salty, with the occasional bitter concept album. Coldplay hits those notes when necessary—a political statement here, a song with Rihanna there—but invariably returns to the mushy middle of their sweet spot.

Cozies: Murder without Death

Death is the original plot point. The very first stories were likely about death, functioning as both a memorial to the fallen and a warning to survivors. Among the oldest written works are the Pyramid Texts of ancient Egypt, which are basically a reincarnation manual for recently deceased pharaohs. (The fact that pharaohs had to be dead to read them also meant this was the first paywall in recorded history.) Tragedies were the first of the Greek genres, Shakespeare’s greatest plays are his tragedies, and there’s a reason you should never bet on a comedy to win best picture.

Another common thread that goes back to the beginning of narrative: pattern recognition. We learn from others’ mistakes and get a small thrill when we can use previously assimilated knowledge to figure out where a story’s going to go. It’s life as a giant crossword puzzle.

Combining these two phenomena explains the enduring appeal of the murder mystery, and the serial format. Once you figure out whodunit, it’s on to the next Maigret mystery, or Miss Marple story, or Hercule Poirot adventure, or Sherlock Holmes case. The more of them you read, the more you want to read, and even if you get better at figuring out which of the hired help was responsible (hint: the butler), getting to the end still scratches a deep itch.

But what if there were a way to enjoy the thrill of solving the puzzle without having to think about death, however fictionalized? Could you, in other words, reformulate the murder mystery to play down the murder and play up the mystery?

This is, in essence, the subgenre known as the cozy. The most well-known example is not a book but the long-running TV series Murder, She Wrote, on which mystery author Jessica Fletcher solved homicide after homicide in the small Maine town of Cabot Cove. In print as on television, these are what we might call gentle murders. Writing about the then-new literary trend in 1992, New York Times crime columnist Marilyn Stasio declared these books “remarkable for their nonthreatening content and nonviolent characters.” She identified the characteristics of a cozy, which include amateur and usually female detectives, small-town settings where “the atmosphere is designed to give pleasure and comfort,” and as little violence as is possible.

Erin Martin, the self-proclaimed “cozy mystery list lady” and proprietor of cozy-mystery.com, describes the genre as follows:

Most often, the crime takes place “off stage” and death is usually very quick. Prolonged torture is not a staple in cozy mysteries! The victim is usually a character who had terrible vices or who treated others very badly. Dare I say . . . the victim “deserved to die”?

Once the unpleasant business of the homicide is dealt with, tea can be made and puzzles can be untangled.

The cozy genre covers a wide swath of territory, some parts of which are self-consciously silly and others that are no less gripping for their lack of grit.

Louise Penny’s series featuring Chief Inspector Armand Gamache, head of homicide for the Sûreté du Québec, are harder cozies, and she has eloquently explained why her particular take on the murder mystery wasn’t about the murder.

“That’s simply a catalyst to look at human nature,” she told Publishers Weekly in 2009. “They aren’t about blood but about the marrow, about what happens deep inside, in places we didn’t even know existed.”

Or as Charles Isherwood put it in a New York Times review, “Ms. Penny’s books mix some classic elements of the police procedural with a deep-delving psychology, as well as a sorrowful sense of the precarious nature of human goodness, and the persistence of its opposite. . . .”

And then there are the cozies that feature knitting patterns (Knit One, Kill Two, Needled to Death, and Purl Up and Die), cats (some of whom can talk and others who don’t; the two camps have their fierce devotees), or recipes (Diane Mott Davidson’s bestselling series featuring caterer Goldy Shulz, who perfects recipes and solves crimes in titles like The Whole Enchilada and Dying for Chocolate).

The audience for these books is, not surprisingly, older and female. A US survey conducted in 2010 found 70 percent of one thousand mystery readers polled were female and over the age of forty-five. The older readers were less interested in darker stories, and 40 percent of the respondents said they were always in the middle of a mystery.

When we look at where mysteries fall in the entertainment categories, there’s a pretty even split between communal and thrilling. A mystery TV show is slightly more thrilling than communal, while a mystery novel is thrilling, communal, and aesthetic, in that order. If we wanted to amplify the communal aspects, we’d play up the focus on people and relationships.

In our system, that means we’d ensure the overall taste was more sweet than sour. And for a mystery in particular, that means playing up the characters and the puzzle, playing down the thrills and adventure, and making sure the story as a whole was not so challenging as to slow consumption. It needs to be a solvable puzzle, in other words.

And that’s the recipe for a genre so durable it’s an industry. The cozy trend rises and falls. It began in earnest as a gentle backlash to Thomas Harris’s The Silence of the Lambs, when it became apparent that a significant portion of the marketplace would prefer Hannibal Lecter’s meal of a human liver with fava beans and a nice chianti to be a bit more . . . cruelty-free. The cozies were challenged again by Stieg Larsson’s The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo and all the dark Nordic noir that followed. And the genre suffered some self-inflicted wounds from, in the words of Marilyn Stasio, authors “who seem to think that all you have to do is make the hero an idealized version of yourself, fabricate some anecdotal situations for an eccentric group of characters attending a cooking school, solve a murder or two over dessert, incorporate a few recipes into the text and put a cat on the cover.”

There are always serial killers lying in wait, and sometimes they steal all the attention. But like a cat finding his way to his owner’s lap, the cozies always come back: challenging, comforting, and just sweet enough to leave readers wanting more.

Bronies: Finding Sweet Solace

When I was a child, I spoke as a child, I understood as a child, I thought as a child; but when I became a man, I put away childish things.

—1 CORINTHIANS 13:11

When I became a man I put away childish things, including the fear of childishness and the desire to be very grown up.

—C. S. LEWIS

What happens when society expects you to grow out of your taste for the sickly sweet, but the sweet tooth persists? You may find yourself the only adult in a roomful of children. You may find it difficult to share your enthusiasms with your peer group. You may find yourself the target of some concerned glances. You may be a brony.

The bronies were incepted on October 10, 2010, when a reboot of the My Little Pony animated series titled My Little Pony: Friendship Is Magic debuted on The Hub, a little-watched American cable channel. Like pretty much every other animated series from the 1980s, the original My Little Pony was just a show-length advertisement for toys based on the characters—so really, the characters were based on the toys. This was the case with He-Man, Transformers, Strawberry Shortcake, G.I. Joe, and many more. What marketers today call native advertising—creating ads that are indistinguishable from the actual content the ads theoretically pay for—was standard programming fare for a generation of children. And Hasbro, the corporate rancher who owned those ponies, was also a part owner of The Hub.

To bring My Little Pony back to the small screen, the company turned to Lauren Faust, a writer and artist on The Powerpuff Girls. Faust helped redesign the characters in a distinctly anime way: larger eyes, brighter colors, sparklier sparkles. To look at a My Little Pony from the 1980s next to one from the 2010s is like looking at a dinosaur next to a bird: evolution in action. Similarly, the plots and pacing were radically updated to fit into a significantly smarter popular culture. Since the rise of Pixar, it had become expected that animated films have at least some appeal to the adult chaperones of the target audience, and the ponies were no exception. Faust was the perfect person to make this happen: as a fan of the original My Little Pony, she felt a duty to bring some intelligence to the magical land of Equestria. “If we give little girls a respectful interpretation of the things they like—if we dare to take it as seriously as they do—we will see for ourselves that it’s not so silly after all,” she wrote in a foreword to The Elements of Harmony, the snappily named official guidebook to the series. “We can truly appreciate the merit they see in it. And, amazingly, we can enjoy it for ourselves.”

That “we” included people like Luke Allen, a thirty-two-year-old computer programmer who told WIRED magazine in 2011 that the “weird alchemy that Lauren Faust tapped into when she set out to make the show accessible to kids and their parents hooks into the male geek’s reptilian hindbrain and removes a lifetime’s behavioral indoctrination against pink.” Hence bros who like ponies, or bronies.

The hive mind of that particular reptilian hindbrain was 4chan, an anonymous bulletin board site that, as both supporters and detractors would agree, represents the purest state of what a particular corner of the Internet can be. According to a history of the brony conversation written by Una LaMarche in the New York Observer, it was actually an opinion piece on a comics news blog decrying the corporate control and lack of creator control in the new My Little Pony that first raised interest in the reboot. “Nobody denies that The Hub’s shows will perform well and fulfill the programming needs of the network,” wrote Amid Amidi on Cartoon Brew. “But then again, nobody suggested that Smurfs, Snorks, and Pound Puppies wouldn’t do well in the 1980s either.”

“It was pretty alarmist, but it also got a lot of us going over to watch the show,” original brony Nanashi Tanaka told LaMarche. “We were going to make fun of it, but instead everybody got hooked. And then the first pony threads exploded.”

And so the 4chan community was the first to ask what everyone who encounters a brony must eventually think: Is this for real? And if so, is there something unsavory about it? This conversation took a much more obscene form, of course, which only reinforced the brony message of love, friendship, and rainbows. An awkward truce was reached, but not before the bronies spread onto the wider web.

As the name Hasbro began to describe the company in a new way—they now had bros, whether they wanted them or not—the merchandisers made sure these grown men had plenty of collectibles to collect.

“We are sort of stepping back and seeing how the customer is interacting with our brands in a way we haven’t dreamed of and we like to see where it is going,” the company’s senior vice president of franchising and marketing told the trade magazine License! Global, though the article made clear that “[t]he Hasbro evergreen is typically marketed to young girls ages three to six, and Hasbro admits the series’ growing adult fan base is a surprise.” Cultural studies journals called it transgressive fandom; business analysts called it a lucrative market.

So to reiterate: Is it for real? And if so, why do grown men like culture designed for little girls? The answer to the first question is undeniably yes, and the proof is both how long the subculture has been around and how much its members have spent on merchandise. (At a basic economic level, if you like something ironically and buy mass quantities of it, your irony has become a moot point. Ask anyone who wears Old Spice deodorant.)

So why do bronies exist? It’s been argued that it’s because My Little Pony: Friendship Is Magic caters to them with inside jokes, like an homage to The Big Lebowski (Jeff Letrotski is introduced in season two when the ponies go to a bowling alley) or an elaborate Star Wars montage. This is true, though these elements were only introduced in the second season, another sign of Hasbro’s marketing savvy. Back when the first season caught on, critics suggested that the simple cartoon plots were appealing to young men specifically because they didn’t try to be clever and knowing. So maybe these two sides of the same argument effectively cancel each other out. A similarly suspect rationale for the bronies is the high-quality animation of the show—but if that’s all it takes to get men into cartoons, why didn’t Frozen become Brozen?

One of the more convincing theories was floated by Mary H.K. Choi in WIRED, and it goes like this: The 1980s versions of these commercials-as-cartoons were horrible, but the toys they sold were cool. Kids had epic playdates with the ponies, and they remember those moments fondly. “Armed with the toys, we churned out ur-fanfic that spackled over the holes left by the shows’ crappy dialog and lazy mythology,” Choi writes. So the new shows, which are better in every way, remind viewers of their childhood playtime.

Except heteronormative men who grew up in traditional 1980s households likely never played with My Little Ponies. (Hasbro sold them G.I. Joes.) So how are they nostalgic for something they never had? The Portuguese word “saudade” may fit the bill. Deeply linked to the Portuguese and Brazilian temperaments, it was described by the Englishman A.F.G. Bell as “a vague and constant desire for something that does not and probably cannot exist, for something other than the present, a turning towards the past or towards the future, not an active discontent or poignant sadness but an indolent dreaming wistfulness.”

Why didn’t Frozen become Brozen?

And isn’t any BronyCon, as their conventions are known, a gathering of indolent, wistful dreamers?

Yet more brony research—and there is an impressive amount of it—conflicts with this theory, as, in the words of one cultural studies researcher, “many Bronies claim to be unfamiliar with previous My Little Pony incarnations and some even show disdain for the earlier versions, which suggests that nostalgia is not much of a factor in their dedication to FIM [Friendship Is Magic].”

This academic, Venetia Robertson, discusses all of the above possible explanations for bronydom—the animation style, the in-jokes, the pop-culture references—before ultimately settling on a simpler but deeper motivation: a need to belong. “The ponies provide an avenue for authentic self-expression and reification within the bosom of a community that supports and shares these goals. Bronies are not just among fellow fans, men, and geeks, but individuals turning to anthropomorphic animal media to seek an authentic experience of selfhood.” In this sense, My Little Pony is an oddball example of cultural preference at its most basic: members of the same tribe like the same things, and liking those things admits you into that tribe.

In other words, everypony needs to be somepony, somewhere.

The best way to understand the bronies is, of course, to see where they fall in the Elements of Taste. From this perspective, their fandom makes perfect sense. Sweetness is all about that which is lighthearted, gentle, and focused on relationships, and it skews young and female. It would be hard to identify a cultural artifact as purely sweet as My Little Pony: Friendship Is Magic.

The first-wave bronies (yes, that’s what we’re calling them) emerged from the depths of Internet culture, an arena that is alternately more sour, salty, bitter, and umami than it is sweet. Sweetness, then, is what they were missing. And by using My Little Pony to fight back against their 4chan antagonists, they unwittingly created a movement—one that was eagerly encouraged by a multinational toy company. The lesson here is that you never lose your sweet tooth, and though age and gender may change how much of it you require, you still need some sugar; it’s called a universal taste for a reason. The central premise of My Little Pony: Friendship Is Magic is that each pony represents one element of harmony and only by working together (friendship!) can they ultimately triumph (magic!). By embracing their sweet sides, the bronies are finding balance.

They’re also finding that there’s more to life than My Little Pony. As Shaun Scotellaro, the founder of brony hub Equestria Daily, reflected wistfully on the ebbing popularity of his passion in 2015: “There is no denying that 2012–2013 was our major fandom peak,” he wrote. “This was that point in time where it was essentially ‘the thing’ to rock a Rainbow Dash avatar on your favorite message board or gaming service.”

But though his brothers had moved on, he insisted their love survived, nurtured with plastic merchandise and at conventions. His bronies could run free, “and the massive core base that is always here welcomes them back with open hooves.” Take it as good news for everyone except maybe Hasbro: bronyism, defined as an unexpected and unrestrained love for all that is sweet, will live on long after Pinkie Pie, Twilight Sparkle, and the rest of Equestria have been put out to pasture.

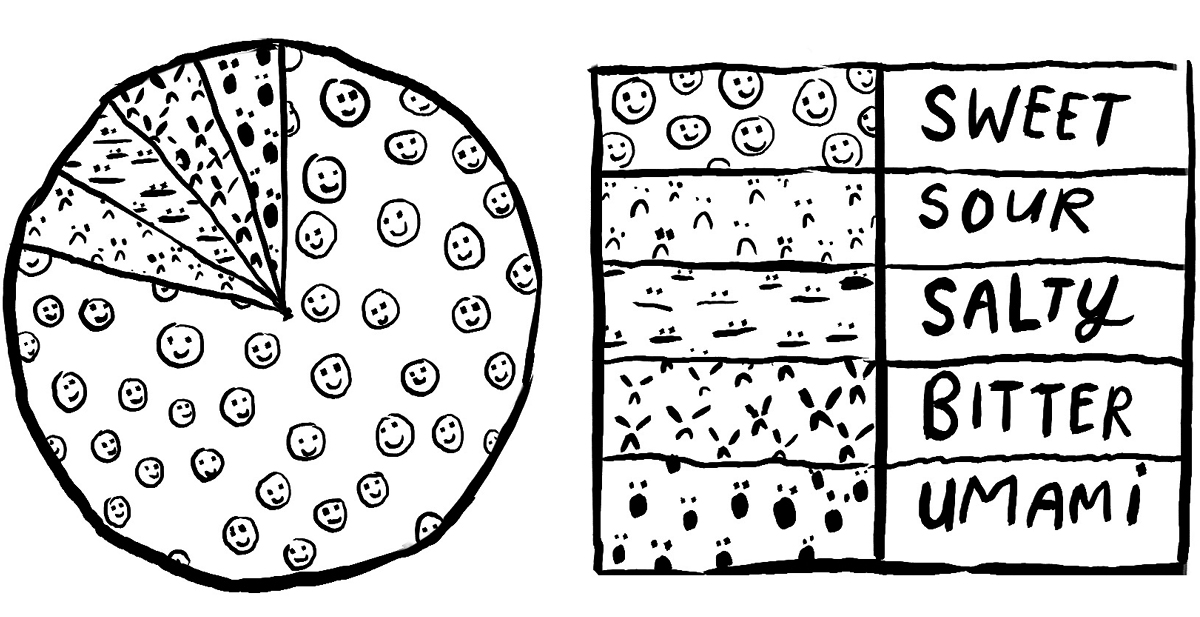

TASTING NOTE: FRIENDS

Sweet: 80 percent

Sour: 5 percent

Salty: 5 percent

Bitter: 5 percent

Umami: 5 percent

Sitcoms are sweet by definition: Lighthearted, communal, over in twenty-two minutes, and full of hugs. The audience should laugh with the characters, relate to their problems, and (in the days before binge-watching) look forward to seeing them at the same time next week. In other words, these attractive, tightly scripted, two-dimensional people should be our friends. Ergo, Friends. The six well-off, straight, white, twentysomething New Yorkers were like family to one another—and to thirty million viewers on Thursday nights from 1994 to 2004—without actually being family. There had always been sitcoms focused on friendships instead of family or work relationships, but none so sweetly as Friends. Whereas Seinfeld prided itself on “no hugging, no learning” and Cheers followed a bunch of middle-aged barflies, Friends was a sitcom about warm, young, pretty, funny people who would be there for you ’cause you’re there for them too. It remains the most huggable sitcom ever aired.

Beanie Babies: Cultural Sugar Highs

We all like sweet things—but what happens when we all like sweet things?

There are housing bubbles and tech bubbles, but there are also a significant number of bubbles that smell like bubblegum. In these collective sugar highs, the communal side of sweetness can look a lot like a stampeding mob.

The history of bubbles traditionally begins in Holland in the 1630s, when the Dutch came down with a bad case of tulipomania. Bulbs of the flower commanded ludicrous prices, and every Dutchman, Dutchwoman, and Dutchchild jumped into the market. As Charles Mackay’s famous (if not entirely accurate) book Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds put it: “In 1634, the rage among the Dutch to possess [tulips] was so great that the ordinary industry of the country was neglected, and the population, even to its lowest dregs, embarked in the tulip trade.”

Why tulips? Not because they had any practical use, but precisely because they didn’t. Holland was the wealthiest nation in Europe at the time, and with that wealth came a desire for some conspicuous consumption.

The beauty of the tulip bubble is that it was based on beauty; if people thought that this particular commodity would forever increase in value, it was in part because they simply liked the way it looked.

And in that respect, Beanie Babies were the tulips of the United States in the 1990s.

How exactly Beanie Babies grew into a phenomenon that eclipsed such previous toy hits as Cabbage Patch Kids is a lurid story told in Zac Bissonnette’s 2015 book The Great Beanie Baby Bubble. The elements included “localized variations in knowledge about rare Beanie Babies,” the emergence of the Internet as a cultural force, and a vigorous legal strategy. There were stories of average people making huge amounts of money from stuffed bears. (This fed what economists call the greater fool theory: any price can be justified if you think someone will pay more.) And then came eBay, a perfect place to auction Beanie Babies for whatever the market would pay.

But most of all, it was because they were cute. Creator Ty Warner knew how to make a sweet plush toy—in a word: eyes. They need to be well-spaced, shiny, and never, ever obscured by fur. And Warner invested enough in the process—even trademarking the word “poseable”—to set his products apart on toy-store shelves. As one reseller told Bissonnette, the Beanie Babies were “something really cute that just brought out the worst in people.” They were collected by “creepy, belligerent men” and couldn’t be given to kids with cancer because their parents kept trying to confiscate and resell them. Then there was the sad tale of a murder that resulted from a fight over Beanie Babies, leading to the defining quotation of the Beanie bubble: “I cannot go to prison as the Beanie Baby Killer. I’m gonna have to kill someone else just to get my credibility back.”

Even after the crash, the sugar high had a lasting effect. Just as tulipomania created Dutch horticulture, the Beanie Baby boom helped create the Internet as an economic force. Is it too much to say we are living in a world built by Beanie Babies? Yes, it is. But still.

Our natural affinity for pretty, useless things doesn’t always have to end in ruin. Sometimes, under the right conditions, we can sustain ourselves for generations on a steady drip of sweetness. Consider the prettiest commodity of them all, the soft, shiny metal hoarded throughout history because of its—well, why is gold so valuable? You may well ask yourself that when you’re gnawing on your hoarded ingots after the apocalypse. For now, though, just be happy you didn’t stockpile useless flowers or poseable stuffed animals.

Sweet Sounds

“I’ve never seen you looking so lovely as you did tonight,” Chris de Burgh crooned. “I’ve never seen you shine so bright.”

That was the most I could take. I was sitting in an airless office, volunteering my time to stuff envelopes for a reputable charity. The radio was locked on the local lite-rock station, which may or may not have featured E and Z in its call letters. Its smooth tunes at a reasonable volume helped the middle-aged staff ease through their workday, but my late-adolescent eardrums would have preferred a sharpened pencil. In between ads for mattresses and weight-loss clinics, they played the most excruciating music. Phil Collins, Elton John, George Michael, and Billy Joel were the four horsemen of my mind-numbing afternoon, and they were at the service of Mr. de Burgh. I wanted this volunteer-service line on my résumé, but at what cost?

The day I heard “Lady in Red” twice in an hour—my second time volunteering—I submitted my resignation. Well, not really: I just told the nice lady with the jar of Werther’s Originals on her desk that my coursework was too demanding to allow my further stuffing of well-intentioned envelopes. I didn’t tell her this music was torture. I didn’t tell her that if young men in their teens and twenties had been invited to the Geneva Convention, easy rock would have been inserted right between drowning and electrocution. Also, there would have been a lot more horseplay.

For the decade or so that followed, I managed to keep a safe distance from any sort of lite, light, EZ, easy, smooth, diet, or soft rock. I would opt for indie, math, sweater, hard, or, in a pinch, Kraut rock, but never anything easy. Sure, there was some Belle and Sebastian in there, but those sensitive Scots wouldn’t dare turn on a synthesizer unless it was really, really necessary.

In that sense, I was unthinkingly going through the tastemaking process that Carl Wilson elegantly described in his 2007 masterpiece Let’s Talk About Love: Why Other People Have Such Bad Taste. Wilson has a much better—or much worse—Chris de Burgh in Celine Dion, and he works through his disdain so thoroughly in the book that by the end, listening to “My Heart Will Go On” nearly brings him to tears. Nearly: “While my eyes didn’t well over, neither were they completely dry.”

My evolution was much less profound, as it was spurred by a conversation with a friend about perhaps the most benign subject two young men can discuss: the late and lamented Guitar Hero. He had spent a weekend playing it, and I confessed that I hadn’t gotten the hang of the video game.

“I just don’t have any rhythm,” I told him.

“Is it because you have guilty feet?” he asked.

“Ha,” I responded. “My feet were never formally charged.”

From that, the earworm had been planted. Those tawdry saxophones were ringing in my ears. I found myself looking for the Phil Collins song “Guilty Feet” the next day at work, only to learn that it was George Michael who had named his song “Careless Whisper.”

Once I’d watched it on YouTube a few times, I was hooked. I heard it while waiting in line at IKEA and found myself swaying to the beat, arms full of tea lights. I promptly made it my karaoke song.

From Mr. Michael, the slide into back-to-back commercial-free soft-rock hits was a steep one, and I had company on the descent. Because everybody knows these songs. Everyone wants to know what love is. Everybody wants to dance with somebody. Everybody wants to rule the world. And then there’s “Africa,” a song that first irritated me on K-Tel commercials but now speaks to me on a deep, danceable level.

Everybody wants to rule the world.

How did this happen? I didn’t think through my tastes and prejudices. It just happened. Occam’s razor would suggest that I had simply become lame. The fact that I thought Tron: Legacy was way too loud would seem to back that up. But for the sake of my self-esteem, let us discount that possibility.

The same researchers who developed the MUSIC model discussed at the beginning of this book later examined how musical preferences change throughout our lives, and they confirmed some cultural truisms: young people listen to more music in more contexts than people in middle age, and with age comes less interest in the intense and contemporary and more time for the sophisticated. “Raising a family and pursuing a career provide adults with defining features of their identities. It seems reasonable to suggest that the meaning derived from these roles diminishes the function that music serves in shaping identity and offering fulfillment,” the researchers write. It doesn’t have to define you; it just has to fill the background.

There is some comfort in knowing I’m not alone. The cultural reappropriation of easy listening is happening, albeit in a niche way. Take “As Above So Below,” a Klaxons song remixed by Justice that’s actually a distorted cover of the Doobie Brothers’ “What a Fool Believes.” The original was a song my father would play on repeat on family road trips, and it was rendered suitable for a sweaty dance club. Bands like Miami Horror and Chromeo back this up with their reinterpretations of Supertramp and Hall & Oates, respectively. But while they may offer some artistic cover for my cravings, they can’t really satisfy them like the originals. They’re like drinking a Jones Cola with real cane sugar when all you really want is that high-fructose corn syrup Coke fix: unarguably better but not what hooked you in the first place.

If rock ’n’ roll is all about rebellion, frustration, and youth—the sour—then lite rock is about conforming, adapting, and aging. It’s sweet, but just a bit bitter. In “Lady in Red,” he’s not trying to pick up that gorgeous babe; he’s just appreciating her again for the first time. “Someone Saved My Life Tonight” expresses relief over avoiding a loveless marriage. These songs are not designed to be cranked while taking Dad’s car to the mall. They’re for when Dad’s car is your car. They’re all kind of sad, actually: that melancholy nostalgia that once again calls to mind the bittersweet phenomenon of saudade.

(In this respect, the origin story of “Careless Whisper” only improves the song. George Michael wrote this singular work of art when he was seventeen. He had never been in a serious relationship. All of the lyrics are bits of melodrama he picked up while working as a cinema usher. It’s a gloss on a gloss, a Hollywood version of doomed romance perfected by a clever kid and embraced by actual adults the world over. Who better to mope over lost love than a precocious teenager?)

And maybe that’s why I finally began to appreciate lite rock. It’s been documented that the glummest time of life is early adulthood. Stress, worry, anger, and sadness all creep toward their lifetime peaks in middle age. But once you get past your midforties, you’re statistically due to start feeling better about things. At that point, I may be ready to turn up the Public Enemy. Until then, well, it’s a little bit funny, this feeling inside. Deep inside, I hope you feel it too.

TASTING NOTE: THE NOTEBOOK

Sweet: 100 percent

Sour: 0 percent

Salty: 0 percent

Bitter: 0 percent

Umami: 0 percent

The 2004 movie that launched the careers of Ryan Gosling and Rachel McAdams is the cultural equivalent of high-fructose corn syrup. The whole setup is that the aged pair (played by James Garner and Gena Rowlands) are reminiscing about their temporarily unrequited love as recorded in (yes) the Notebook, removing any doubt that they end up together. To call it formulaic is an understatement; this is a movie that found new resonance in Hollywood’s oldest story through flawless execution. Boy meets girl, boy loses girl, boy wins girl back, boy kisses girl in the rain, boy and girl live long, fulfilling lives together and die in each other’s arms. Throw in World War II, James Marsden, and a Ferris wheel, and you’ve got a Hollywood romance sweet enough to rot the teeth of an entire generation.

Sweet Smarts

The knock against sweetness, both in physical and cultural taste, is that it is so frequently overdone. Just as there is sugar added to spaghetti sauce for no good reason, so too are happy endings added to movies whether they make sense or not. In both instances, the result is cloying.

Our world is so saturated in sugar that it’s only logical to limit your intake after a while. But while a sugar-free diet may actually be nutritionally sound, cutting out sweet culture is as inadvisable as it is difficult.

Sweetness is correlated with innocence, and is inversely proportional to experience. The common extension of this is that warm and fuzzy feelings are for children, and the older and more educated we become, the harder our hearts must get. There’s the old saw about how if you’re not a liberal when you’re young, you don’t have a heart, and if you’re not a conservative when you’re old, you don’t have a brain. The underlying logic is that as the heart’s power recedes, the brain must take over.

In fact, the opposite is true. The writer George Saunders explained this simple concept in his speech to the 2013 graduating class of Syracuse University. As a recipient of MacArthur and Guggenheim grants, Saunders is as certifiable a genius as exists in literature. The one piece of wisdom he chose to impart, above all others, was to simply be kind to one another.

By his reasoning, this shouldn’t be something you know as an innocent child and forget as an experienced adult, but rather the opposite. As you age and if you are lucky, you will realize there are three fundamental lies we all start out believing:

“(1) we’re central to the universe (that is, our personal story is the main and most interesting story, the only story, really); (2) we’re separate from the universe (there’s US and then, out there, all that other junk—dogs and swing-sets, and the State of Nebraska and low-hanging clouds and, you know, other people); and (3) we’re permanent (death is real, o.k., sure—for you, but not for me).”

The older you get, the fewer excuses you have for not questioning these beliefs. As Saunders points out, everything from friendships to religion to education to children serves to teach us that it’s not about us. We are small, temporary, and insignificant—with the ability to become kind, loving, and luminous, should we choose this route. This idea is represented throughout culture by the Kindhearted Simpleton, or the Moral Moron. He is Shakespeare’s Falstaff and Dostoyevsky’s Idiot, Hanks’s Forrest Gump, and Buscemi’s Donny Kerabatsos.

This may be so hard to grasp because it’s so simple. Missing this point is confusing the sweet with the saccharine.

Sweetness, then, is the starting point but also the ideal place to end up. It’s the middle part—the experience that comes after innocence but before awareness—that we’re prone to get stuck in. If sweet culture is defined by people and relationships, it really is the thing that matters. All the other tastes are worth sampling, to be sure, and there are great things to be found in their many combinations and permutations. Ideally, though, you come back to a note of sweetness. And then you really appreciate it.

“Because kindness, it turns out, is hard,” Saunders told the graduates. “It starts out all rainbows and puppy dogs, and expands to include . . . well, everything.”