The Talmud is made up of compositions that set forth, beginning to end, a sequence: [1] proposition, [2] argument, and [3] evidence, together with what we should now call footnotes and appendices: all the information necessary to follow a complete, and sustained, thought. The Bavli’s authorships followed not only rules of language but also laws of composition. These laws told them what issues must come first, which ones may be treated later. Furthermore, if we classify the rhetorical laws that governed the translation of thought into formal prose, we readily identify certain patterns (“forms” in a very broad and loose sense), and we can show a close kinship between a rhetorical form and the logic that infuses statements made within the model of that form with coherence and cogency. Can I identify the “forms” (in the sense just now defined)? Can I show that all authors employ the same limited repertoire of forms, and, further, that they make use of these forms in the same, fixed order—form A always prior to form B, type of composition C always prior to type of composition D—throughout the document? Then, if I can, I shall know the rules of composition. These seen altogether I characterize as the Bavli’s one voice,

That is because the Bavli, a remarkably cogent document, speaks in a single voice about some few things and says the same thing about everything. That statement will surprise people who have not studied the Talmud from a critical perspective but who concentrate on the ad hoc exegesis of free standing sentences and paragraphs, not on whole units of thought. The run-on and meandering quality of a Talmudic discussion however is difficult to analyze as a single, cogent composition, and therefore impossible to classify as the work of showing how the Bavli’s one voice speaks, until we realize a simple fact. The Talmud of Babylonia in contemporary terms would be presented heavy with footnotes and weighted down by tacked on appendices.

That is, in our mode of setting forth our ideas and the documentation for them, we include in our text the main points of proposition, evidence, and argument; we relegate to footnotes the sources upon which we draw; we place in appendices substantial bodies of secondary material, relevant to the main body of our text only tangentially, yet required for a full presentation of what we wish to say. The authorship of the Talmud of Babylonia accomplishes, within the technical limitations that governed its formulation of its proposition, evidence, and argument, what we work out through footnotes and appendices. Much of the materials subordinated to the proposition, evidence, and argument, derives from finished pieces of writing, worked out for use in a document we do not now have (and cannot even imagine!), now providing useful, if not essential, documentation for the document that we do have.

In classifying a piece of writing, a composition within a composite that constitutes a complete and fully articulated discourse, I must and should include within my scheme the entire mass of not only proposition, evidence, and argument, but also footnotes and appendices. The whole then is treated as what has been classified, even though only parts form that active and determinative discussion. Accordingly, I include within a given act of classification not only what is relevant to the flow and thrust of discourse, but also the associated documentation, meaning, everything upon which the framers drew, then the whole of the Talmud under discussion will be seen fully to fall into place in accord with the proposed rules of composition. A protracted passage, which seems run-on, when properly set forth, forms a cogent and coherent statement: proposition, evidence, arguments, fully exposed, but, alas, glossed and amplified and extended through footnotes and appendices as only intellectuals who also are scholars can gloss, amplify, and extend their remarks.

What do I mean by “one voice”? A fixed rhetorical pattern and a limited program of logical inquiry governs throughout. Whatever authors wish to say, they say within a severely restricted repertoire of rhetorical choices, and the intellectual initiatives they are free to explore everywhere dictate one set of questions and problems and not any other. The document’s “voice,” then, comprises that monotonous and repetitious language that conveys a recurrent and single melody, The document as a whole is cogent, doing some few things over and over again; it conforms to a few simple rules of rhetoric, including choice of languages for discrete purposes, and that fact attests to the coherent viewpoint of the authorship at the end—the people who put it all together as we have it—because it speaks, over all, in a single way, in a uniform voice. It is not merely an Encyclopaedia of information, but a sustained, remarkably protracted, uniform inquiry into the logical traits of passages of the Mishnah or of Scripture. Most of the Talmud deals with the exegesis and amplification of the Mishnah’s rules or of passages of Scripture. Wherever we turn, that labor of exegesis and amplification, without differentiation in topics or tractates, conforms to a few simple rules in inquiry, repeatedly phrased, implicitly or explicitly, in a few simple rhetorical forms or patterns.

We therefore have very good reason to suppose that the text as we have it speaks about the limited context of the period of the actual framing of the text’s principal building blocks. These building blocks give evidence of having been put together in a moment of deliberation, in accordance with a plan of exposition, and in response to a finite problem of logical analysis. The units of discourse in no way appear to have taken shape slowly, over a long period of time, in a process governed by the order in which sayings were framed, now and here, then and there, later and anywhere else (so to speak). Before us is the result of considered redaction, not protracted accretion, mindful construction, not sedimentary accretion. And, as I said at the outset, the traits of the bulk of the Talmud of the Land of Israel may be explained in one of only two ways. One way is this: the very heirs of the Mishnah, in the opening generation, ca. A.D. 200-250, whether in the Land of Israel or Babylonia,1 agreed upon conventions not merely of speech and rhetorical formulation, but also of thought and modes of analysis. They further imposed these conventions on all subsequent generations, wherever they lived, whenever they did their work. Accordingly, at the outset the decision was made to do the work precisely in the way in which, four hundred years later—the same span of time that separates us from the founding of New England, twice the span of time that has passed since our country became an independent nation!—the work turns out to have been done.

The alternative view is that the work was done all at one at the end of time. Some time late in the formation of diverse materials in response to the Mishnah (and to various other considerations), some people got together and made a decision to rework whatever was in hand into a single, stunningly cogent document, the Talmud as we know it in the bulk of its units of discourse. Whether this work took a day or a half-century, it was the work of sages who knew precisely what they wished to do and who did it over and over again. This second view is the one I take. The consequence is that the Talmud exhibits a viewpoint. It is portrayed in what I have called “the Talmud’s one voice.”

In claiming that we deal not only with uniform rhetoric, but with a single cogent viewpoint, we must take full account of the contrary claim of the Talmud’s framers themselves. This claim they lay down through the constant citations of sayings in the names of specific authorities. It must follow that differentiation by chronology—the periods in which the several sages cited actually flourished—is possible. To be sure, the original purpose of citing named authorities was not to set forth chronological lines, but to establish the authority behind a given view of the law. But the history of viewpoints should be possible. True, if we could show, on the basis of evidence external to the Talmud itself, that the Talmud’s own claim in attributing statements to specific people is subject to verification or falsification, such a history can be undertaken; but it will not lead us into a deeper understanding of the document before us, not at all. All it will tell us is what this one thought then, and what that one thought later on; the document before us has put these things together in its way, for its purposes, and knowing that Rabbi X really said what is assigned to him in no way tells us the something we otherwise do not know about that way and those purposes. In any case, the organizing principle of discourse (even in anthologies) never derives from the order in which authorities lived. And that is the main point. The logical requirements of the analysis at hand determine the limits of applied and practical reason framed by the sustained discourses of which the Talmud is composed.2

The Bavli’s one voice governs throughout, about a considerable repertoire of topics speaking within a single restricted rhetorical vocabulary. So “the Bavli’s one voice” refers to a remarkably limited set of formal and intellectual initiatives, only this and that, initiatives that moreover always adhere to a single sequence or order: this first, then that—but never the other thing. I can identify the Bavli’s authorships’ rules of composition,. These are not many. Not only so, but the order of types of compositions (written in accord with a determinate set of rules) itself follows a fixed pattern, so that a composition written in obedience to a given rule as to form will always appear in the same point in a sequence of compositions that are written in obedience to two or more rules: type A first, type B next, in fixed sequence. The Talmud’s one voice then represents the outcome of the work of the following:

[1] an author preparing a composition for inclusion in the Bavli would conform to one of a very few rules of thought and expression; and, more to the point,

[2] a framer of a cogent composite, often encompassing a set of compositions, for presentation as the Bavli would follow a fixed order in selecting and arranging the types of consequential forms that authors had made available for his use.

What is at stake in identifying the rules of composition? It is the demonstration of the well-crafted and orderly character of the sustained discourse that the writing sets forth: learning how to listen to the Talmud’s one voice. Specifically, all authors found guidance in the same limited repertoire of rules of composition. Not only so, but a fixed order of discourse—a composition of one sort, A, always comes prior to a composite of another type, B. A simple logic instructed framers of composites, who sometimes also were authors of compositions, and who sometimes drew upon available compositions in the making of their cogent composites. When we understand that logic, which accounts for what for a very long time has impressed students of the Talmud as the document’s run-on, formless, and meandering character, we shall see the writing as cogent and well-crafted, always addressing a point that, within the hegemony of this logic, and not some other, was deemed closely linked to what had gone before and what was to follow.

And on that basis we see as entirely of a piece, cogent and coherent, large-scale constructions, not brief compositions of a few lines, which therefore become subject to classification whole and complete. So the work of uncovering the laws of composition involve our identifying the entirety of a piece of coherent writing and classifying that writing—not pulling out of context and classifying only the compositions that, in some measure, form constituents of a larger whole. Were we to classify only the compositions, we should gain some knowledge of types of writing accomplished by authors, but none concerning types of writing that comprise our Talmud.

The word “composition” bears the double meaning of [1] composing a piece of writing, and also [2] forming a composite of completed pieces of writing. A composite may indeed be classified with all its parts held together in a coherent formation, meant to serve a single purpose, to make a single type of point. Here we classify the pieces of writing—the composites, made up of compositions—and find out the order in which these types of writing are presented. We shall see that a limited repertoire of syntactic rules instructed an author of a composition in the Talmud of Babylonia on how so to formulate his thought in words as to convey within the intellectual conventions of the document—not merely grammatical or syntactical conventions of the language of the document—whatever issue or idea he wished to address. A counterpart repertoire also determined the range of analysis and inquiry: this, not that. And the premises of the rules for intelligible thought and intelligible formulation of thought defined the document’s frame of reference: how to think, what to think, about what to pursue thought.

By exegesis of the Mishnah, I mean that a passage takes shape around the requirement of explaining the language or meaning of a statement of the Mishnah. A sustained composition (encompassing available materials to be sure) can have taken shape only in response to the challenge of explaining a Mishnah-paragraph. A good example is at the beginning of the tractate Temurah.

I.1 A. The very statement of the Mishnah’s rule contains an internal contradiction. You first say, All effect a valid substitution, which means, to begin with. But then you go on, But if one has effected a substitution, it [that which is designated instead of the beast already consecrated] is deemed a substitute [and also consecrated], and that means, only after the fact!

B. But do you think that All effect a valid substitution, means, to begin with? [If that is your reading, then] instead of raising your problem to the formulation of our Mishnah-passage, address it to the formulation of Scripture, for it is written, “[If it is an animal such as men offer as an offering to the Lord, all of such that any man gives to the Lord is holy.] He shall not substitute anything for it or exchange it, a good for a bad or a bad for a good; and if he makes any exchange of beast for beast, then both it and that for which it is exchanged shall be holy” (Lev. 27:9-10).

C. Rather, said R. Judah, “This is the sense of the Mishnah-passage: All can be involved so as to effect a valid substitution [substitute a beast for one they have first designated as a sacrifice for that the second beast enters the status of the originally-consecrated one]—all the same are men and women. Not that a man is permitted to effect a substitution. But if one has effected a substitution, it [that which is designated instead of the beast already consecrated] is deemed a substitute [and also consecrated]. And the man [who does so] incurs the penalty of forty stripes.

The purpose of the discussion is transparent: the clarification of the meaning of the passage before us. A composition that is classified as Mishnah-exegesis is one that makes sense only within the framework of a Mishnah-paragraph, one that cannot have been composed without the immediate presence of a sentence of the Mishnah. The next composition follows suit.

2. A. All effect:

B. What does the language, “all,” serve to encompass?

C. It serves to encompass the heir [who effects a substitution while the father is still alive. He does not yet own the beast, and only the owner of a beast can designate it as holy. But he is presumed to be heir and therefore future owner of the beast. The legal effect of his presumptive ownership then is at issue.]

D. That is not in accord with the position of R Judah. For it has been taught on Tannaite authority:

E. “The heir of the owner of a beast may lay on hands, and the heir of the owner of a beast may effect a valid substitution,” the words of R. Meir.

F. And R. Judah says, “The heir of the owner of a beast may not lay on hands, and the heir of the owner of a beast may not effect a valid substitution.”

G. What is the reasoning behind the position of R. Judah?

H. It is that R. Judah draws an analogy from the end of the act of consecration for the beginning of the act of consecration. Just as, in the final act, the presumptive heir ofa beast cannot lay on hands [but only the actual owner of the beast does so], so at the beginning of the act of consecration, the presumptive heir cannot effect a valid substitution.

I. Then how do we know the rule governing the laying on of hands anyhow?

J. We find a reference to “his offering” three times [Lev. 3:1, “and if his offering is a sacrifice of a peace offering;” Lev. 3:6, “and if his offering for a sacrifice to the Lord be of the flock;” Lev. 3:7: “and if he offer a lamb for his offering”]. One bears the sense, “his offering,” and not the offering of a gentile; one bears the sense of, “his offering,” and not the offering of somebody else; and the third bears the sense of, “his offering,” and not the offering of his father.

K. And so far as R. Meir is concerned, who has said, “A presumptive heir lays on hands,” do we not have written, “his offering”?

L. He requires that to make the point that all members of a partnership that owns a beast must lay hands on the beast.

M. And does R. Judah not concur that all members of a partnership that owns a beast must lay hands on the beast? How come?

N. It is because their offering is not designated [to belong specifically to any one of the several partners, so the language “his offering” does not pertain].

O. If you prefer, I shall say, in point of fact he does concur [that all members of a partnership that owns a beast must lay hands on the beast], but he derives the rule governing both the offering of a gentile and the offering ofone s fellow from the same verse, leaving over a reference that serves to make the point that all partners in the ownership of a beast that is to be sacrifices lay hands on the beast.

P. And R. Meir, who maintains that a presumptive heir does not lay on hands—what is the scriptural basis for his position?

Q. He will say to you, “ ‘if he makes any exchange of beast for beast, then both it and that for which it is exchanged shall be holy’ serves to encompass the presumptive heir of the beast. ’One then infers from the initial act ofdedication the rule governing the final act of consecration [done just before the animal is killed]. Just as, at the initiation of the process ofconsecration, the presumptive heir may effect a valid act of substitution, so at the end of the process of consecration, the presumptive heir may lay on hands.”

R. And as for R. Judah, how does he deal with the verse, “if he makes any exchange of beast for beast, then both it and that for which it is exchanged shall be holy”?

S. It serves to encompass within the law the power of a woman, and that is in accord with that which has been taught on Tannaite authority:

T. Since the entire passage [governing the act of substitution] speaks only of men, as it is said, “[If it is an animal such as men offer as an offering to the Lord, all of such that any man gives to the Lord is holy.] He shall not substitute anything for it or exchange it,” how do we know that a woman is subject to the same law? Scripture says, “if he makes any exchange of beast for beast,” which serves to encompass a woman.

U. And as for R. Meir, how does he know that a woman is subject to the law?

V. He derives that fact from the language, “and if . . . .”

W. And how does R. Judah deal with that possible proof?

X. He derives no lesson from the language, “and if . . . ”

Y. Now so far as both R. Meir and R. Judah are concerned, the operative consideration is that Scripture has served expressly to include the case of a woman, but if the woman had not been encompassed by Scripture, then I might have reached the conclusion that, if she made a statement of substitution of a secular beast for an already-consecrated one, [while the former may be deemed consecrated], she does not incur the penalty of a flogging.

Z. But has not R. Judah said Rab said, and so too has a Tannaite authority of the household of R. Ishmael stated, “ ‘When a man or a woman commits any sin that men commit’ (Num. 5:6). In this language, Scripture has treated the woman as comparable to the man for the purpose of all the penalties that are imposed by the Torah.”

AA. [The explicit proof in the present instant] is required. For what might you have thought? These words pertain to a sanction that is equivalent for either an individual or the community, but here, since we deal with a penalty that is not equivalent for everybody, as we have learned, A congregation and partners do not produce a substitute, since it is said, “He shall not change it” (Lev. 27:10). The individual produces a substitute, and neither a congregation nor partners produce a substitute,

BB. in consequence of which, a woman also, should do such a deed, would not be flogged. So we are informed that she would be flogged.

No. 2 likewise begins with an interest in explaining the language of the Mishnah. But, it is clear, Mishnah-exegesis is not limited to minor problems of word-explanation, since we forthwith compare what our Mishnah says about a given problem with a contrary position on the same problem, D. This yields a secondary interest in the scriptural source for the contradictory positions, respectively. Each party is given a fair hearing, meaning, a chance to reply to what the other party has to say. The example of course does not exhaust the entire range of compositions and composites (such as what is before us) devoted to, or precipitated by the requirements of, Mishnah-exegesis. But it suffices for purposes of indicating what is classified in the following catalogue:

I:1A-E I.1, 2

1:2A-G I.1-4: How on the basis of Scripture do we know the Mishnah’s rule

1:2H-J.I.1-6

1.3.II. 1: Scriptural basis for the Mishnah’s rule.

1:4-5.I.1, II.1, III.1, IV.1, V.1, VI.1 Who is the Tannaite authority behind the rule?

1:4-5.VII.1, VIII.1, IX.1: Scriptural basis

1:6.I.1, 2 Scriptural basis for the Mishnah’s rule.

1:6.II.1-3 As above.

2:1.I.1. The language of the Mishnah-paragraph is analyzed for its comprehensiveness. Then: who is the authority?

2:1.II.1

2:l.III.1-2(+3)

2:2.I.1. Scriptural basis for the Mishnah’s rule is set forth in a discussion of the relevant verse, so that, in form the composition appears to focus upon the verse at hand; but it is then inserted to answer the familiar questions, what is the scriptural basis for this rule, and who is the authority behind this rule.

2.2.II-III. The composite on the grape-cluster is made up of a number of distinct compositions. These are 2:2.1.2-3, the grape cluster itself. Then comes what was forgotten at the time Moses died, Nos. 4-7. This is followed by a handsome exposition of Josh. 15:17, Nos. 8-13+14-16. At 2:2.II.1L we find out why the entire grape-cluster/laws forgotten when Moses died-composite has been inserted, and it turns out that the whole composite forms a massive, digressive exposition of the Mishnah. On that basis I classify the entire composite as Mishnah-commentary, at the same time recognizing that it has been assembled in its own terms and only later on utilized for the purpose at hand.

2:3.I.1: Scriptural basis for the rule of the Mishnah. This is then spelled out at No. 2.

3:1A-E.I.1, 2-3, 4, 5-10 Language-criticism of the Mishnah; scriptural source of the Mishnah’s rule; practical implication of the Mishnah’s rule; extensions and elaborations of the foregoing

3:1F-N.I.1 Scriptural basis for the position of a Mishnah-authority

3:1F-N.II.1, III.1 Clarification of the language of the Mishnah

3:2A-D I.1 What is the scriptural basis for this ruling?

3:3G-N, 3:4 I.1-3 Why is it necessary for the Mishnah to cover all of the items that it treats? Then No. 2: what is the issue treated by the Mishnah-paragraph? No. 3 pursues a theoretical question formed on the basis of the foregoing.

3:5.II.1 Harmonization of conflicts between two or more paragraphs of the Mishnah.

4:1 I.1-2+3 Explanation of the formulation of the Mishnah’s rule: What is the reason that the Tannaite author of the passage does not state in a single paragraph all five categories . . .

4:2-4 I.1+2-7 We identify the operative principle, then ask who is the authority that holds that principle, and proceed to compare the rule at hand and its premise with other rules that appeal to that premise or its very opposite. This then is a sustained work of Mishnah-exegesis, harmonization of conflicting rules in particular.

4:2-4 II.1 The rule of the Mishnah is brought into relationship with a corresponding Tannaite statement.

5:1-2.II.1 Clarification of the language of the Mishnah & its implications.

5:1-2.III.1, IV.1, 2 Theoretical questions, which clarify the sense and implications of the Mishnah. IV. 1 shows the premise on which our rule rests and permits us to move from the case to an encompassing principle, namely, the point at which the firstling becomes consecrated, and, by extension, the still more abstract and encompassing question of the point at which we deem the potential to be actual. No. 2 depends on the upshot of No. 1 but of course is a free-standing item.

5:3 II.1 Proof that the Mishnah’s rule is not self-evident but had to be articulated, lest a false conclusion be drawn.

5:4 I.1-2 Clarification of what is subject to dispute in the Mishnah’s law. All parties concur on a given proposition but dispute about some more subtle one.

5:5 I.1-2 Implications of the language of the Mishnah explored, with the upshot that the language of the Mishnah is clarified. No. 2 depends upon the result of No. 1.

5:6 I.1 Authority behind the law of the Mishnah.

5:6 II.1 The operative consideration in the law of the Mishnah.

6:1 I.1-2 Clarification of the language of the Mishnah, why specific phrases were required in context. Harmonization of several distinct Mishnah-paragraphs on the same problem.

6:1 I.3 Source in Scripture of the Mishnah’s rule. Nos. 4, 5 are tacked on for obvious reasons, but do not serve the interests of Mishnah-exegesis.

6:1 I.4-6+7 Scriptural exegesis devoted to Lev. 1:32 more or less in its own terms.

6:1 II.1, 2 Clarification of a detail relevant to a rule of the Mishnah. Scriptural proof for a rule of the Mishnah. No. 3 forms a secondary development.

6:1 III.1 How on the basis of Scripture do we know the Mishnah’s rule.

6:2.I.1, 2+3-4 Clarification of the cases to which the Mishnah’s rule pertain. No. 3 is then built on the foregoing.

6:2.I.5 Clarification of the applicability of the Mishnah’s rule.

6:2 II.1 The language and reasoning of the rule of the Mishnah are expounded.

6:3 I.1 Clarification of the language of the Mishnah through introduction of a corresponding Tannaite statement.

6:3 II.1 Clarification of the proof-text of the Mishnah.

6:3 III.1 Explanation of the thinking of the Mishnah’s law.

6:3 IV.1-3 Amplification of the foundation of, the Mishnah’s rule. No. 2 engages in a valuable comparison of categories, and No. 3 does the same.

6:4-5 I.1-2 Amplification of the Mishnah through corresponding Tannaite materials.

6:4-5 II.1 Why specify all of the cases that Scripture and the Mishnah make explicit? Proof that all had to be set forth, one by one.

6:4-5 III.1 The dispute on the Mishnah’s rule is ironed out.

6:4-5 IV.1 Secondary expansion of the positions outlined in the Mishnah.

6:4-5 V.1 Operative consideration behind the law of the Mishnah.

6:4-5 VI.1 Scriptural basis for the rule of the Mishnah.

7:1-2 I.1 Criticism of the Mishnah’s claim to encompass all cases: candidates for a list of exceptions.

7:1-2 II.1 Criticism of the Mishnah’s rule.

7:1-2 III.1 Identification of the Mishnah’s authority.

7:1-2 IV.1 Clarification of the Mishnah’s language.

7:1-2 V.1 Clarification of the coverage of the Mishnah’s law.

7:4-6 I.1 Gloss: harmonization of the Mishnah-paragraph’s rule with an apparently-contradictory law elsewhere in the same document.

7:4-6 II.1 As above.

7:4-6 III.1 Gloss: clarification of the point of reference of the Mishnah.

7:4-6 IV.1 Gloss: amplification of the Mishnah’s rule through a counterpart Tannaite formulation

7:4-6 V.1 Gloss: operative consideration behind the rule of the Mishnah.

By exegesis of the Mishnah’s law, I mean the composition of a discussion that focuses upon not glossing or amplifying or paraphrasing or defending the rule of the Mishnah as formulated, but rather, investigating the principle or premise that underlies a given passage of the Mishnah. At issue in a composite of this kind is not only words or phrases of the Mishnah, but the sense, premise, and implications of the Mishnah’s rule. The discussion will then concentrate on the premise, with the result that by reference to a shared premise—or the opposed premise—two distinct rules, each on a situation not replicated by the other, will be shown to intersect. Then the two or more cases worked out in the context of particular laws will be brought into alignment with the law before us. Since the present classification of discourses is somewhat subtle, let me give a sizable sample of what I conceive to be abstract theorizing in response to, but not as a commentary upon, the Mishnah-paragraph. This seems to me a fair example:

2:3 II.1 A. R. Eleazar says, “A beast that is crossbred and a terefah and one born from the side, a beast lacking in clear-cut sexual characteristics and one which bears both male and female characteristics are not made holy and do not impart [to a substitute] the status of holiness:”

B. Said Samuel, “[Since only the value, but not the body, of these beasts can be consecrated, it follows that] in respect to making an exchange, they are not deemed consecrated, and they do not confer consecration on another beast in an exchange with others.”

C. It has been taught on Tannaite authority:

D. Said R. Meir, “Since they are themselves not holy, how in any event can they confer consecration on other beasts? So you find a possible case only when one has consecrated a beast and it afterward became terefah, or one consecrated an embryo in the mother’s womb and it was born through a caesarean section. But with respect to the cases of a beast lacking in clear-cut sexual characteristics and one which bears both male and female characteristics, you find these cases only with regard to embryos of dedicated beasts [Miller: which were consecrated in virtue of their mother before pregnancy. They are then obviously holy, like a limb of the mother. In these cases the Mishnah informs us that they do not effect an exchange.]”

E. And this accords with the position of R. Judah, who has said, “The offspring of a beast that is consecrated can effect an exchange [with other offspring of consecrated beasts].” [The Mishnah then tells us with reference to these classes of beasts that although they are holy through their mother, they cannot effect an exchange, in spite of the fact that Judah elsewhere maintains that the offspring of a dedicated animal effects an exchange (Miller)].

2. A. Said Raba, “What is the reasoning of R. Eliezer? They are comparable to an unclean beast. Just as an unclean beast is not actually offered, nor does consecration ever affects its body, so these too are not offered, and consecration never affects their bodies.”

B. Said R. Pappa to Raba, “But surely there is the case of a blemished beast, which is not offered, but the body of which is affected by consecration?”

C. He said to him, “True enough, but the species of the blemished beast will be offered [even though this beast will not].”

D. “If so, then a terefah-beast also belongs to a species that will be offered.”

E. Rather, said Raba, “They are comparable to an unclean beast in the following way: just as an unclean beast is invalid in its very body, so whatever is unfit as to its body is subject to the same rule, which excludes the blemished beast which is disqualified by reason of a [Miller:] mere deficiency [but not the condition of the whole body].”

F. Said R. Ada to Raba, “But what about ‘anything too long or too short’ (Lev. 22:23), mentioned in the scriptural passage? These are disqualifications that affect the whole body.”

G. Rather, said Raba, “They are comparable to an unclean beast in the following way: just as in the case of an unclean beast, there is none in its classification that is offered [and the law of exchange does not pertain], so in the case of all beasts in which none in its classification is offered, [the law of exchange does not pertain], excluding then the case of the blemished beast, for in its classification others are offered. Now what will you say to this? The case of the terefah-beast, for in its classification others are offered? There is no parallel to the case ofa blemished animal. An unclean animal cannot be eaten, and a terefah-animal cannot be eaten, which excludes a blemished animal, which can be eaten.”

3. A. Said Samuel, “He who consecrates a terefah-beast—there has to be a permanent blemish if it is to be redeemed.”

B. That yields the inference that people may redeem animals that have been consecrated, so as to feed the meat to the dogs!

C. Rather, say as follows: “It is dedicated in that it is left to die” [and may not be fed to the dogs].

D. And R. Oshaia says, “It is only equivalent to the case of consecrating wood and stone alone.”

E. We have learned in the Mishnah:

F. All Holy Things which became terefah—they do not redeem them. For they do not redeem Holy Things to feed them to the dogs [M. Tem. 6:5F-G].

G. The operative consideration then is that they have become terefah; but if they were terefah to begin with, then we should be able to redeem them [so if one consecrated a terefah-beast, it can be redeemed so as to feed the meat to the dogs, contrary to Samuel’s opinion]!

H. Perhaps the Tannaite authority of the Mishnah-passage just cited takes the view that in the case of any beast, the corpus of which is unsuitable, the consecration of the body does not apply anyhow.

I. Come and take note of the following: R. Eleazar says, “A beast that is crossbred and a terefah and one born from the side, a beast lacking in clear-cut sexual characteristics and one which bears both male and female characteristics are not made holy and do not impart [to a substitute] the status of holiness.”

J. And Samuel said, “[Since only the value, but not the body, of these beasts can be consecrated, it follows that] in respect to making an exchange, they are not deemed consecrated, and they do not confer consecration on another beast in an exchange with others.”

K. It has been taught on Tannaite authority: Said R. Meir, “Since they are themselves not holy, how in any event can they confer consecration on other beasts? So you find a possible case only when one has consecrated a beast and it afterward became terefah.”

L. Lo, if to begin with it was a terefah-beast, consecration of the body never affected that beast.

M. [17B] Samuel can say to you,” Perhaps this Tannaite authority takes the view that in any case in which the animal is not bodily offered or fit to be offered, consecration does not affect the body of the beast and all [Miller: and therefore if the animal were terefah at the outset, bodily holiness does not attach to it. But Samuel himself concurs with the view of rabbis that in the case of a terefah-beast, the animal receives bodily holiness and therefore cannot be redeemed unless it is permanently blemished merely in order to feed the dogs.]”

Samuel’s observation is not required for the amplification of the Mishnah. In fact he draws conclusions for an issue distinct from that raised in the Mishnah, namely, the distinction between beasts consecrated for their value but not for their intrinsic body. The Mishnah does not address such a case, and understanding the Mishnah does not seem to me to require raising that issue at all. It is Samuel who has seen the cases of the Mishnah as a classification of consecrated beasts, and who has further defined what he conceives to be the taxonomic indicator in play: the distinction introduced at the outset. No. 2 then reverts to our Mishnah and finds the operative consideration; but this observation is within the framework of inquiry defined by Samuel. That the principle is subordinated to the abstract theory is then shown at No. 3, where various Mishnah-paragraphs contribute facts toward the solution of a problem. In all, therefore, the composite holds together not by appeal to the exposition of the Mishnah, its language, sources, authorities, or rule, but to a principle encompassed, also, by the Mishnah-paragraph at hand. Since the present composite can have been inserted at a variety of other passages of the Mishnah—as plausibly at M. Tem. 6:5, for one—it follows that the classification of the passage as theorizing in response to the Mishnah’s law but not as part of the exposition of the Mishnah is plausible, and, I think, even required.

2:3.II.1-3

3:2E-H, 3:3A-C I.1 The discussion of the theoretical problem takes the form of investigating the authorities behind the Mishnah’s statement. However, the principle, not the matter of authority, is what is at stake throughout. Interstitial cases form the center of interest, beginning to end. Here is a fine example of the classification at hand.

3:3D-F I.1-2. II.1-2+3 Explanation of the rule of the Mishnah. This leads directly into the issue of how we dispose of a beast that has been consecrated as to its value, not as to its body. II. 1 pursues exactly the same question. No. 3 moves on to yet another pertinent discussion, in which the same issue is raised in principle, now with reference to a new case. So the whole must be deemed, once more, cogent beginning to end. A grasp of the simple principles of composition leaves no doubt as to the matter.

5:1-2.I.1 The Mishnah’s implicit premise is contrasted with a theoretical proposal.

5:3 I.1-3 Theoretical question generated by the Mishnah’s law always the clarification of the Mishnah’s rule’s premise.

5:5 II.1-2 Clarification of the implications of the Mishnah’s statement. While the upshot is to clarify what is before us, the main point is to determine the level of the authority behind the rule of the Mishnah.

7:3 I.1-3 Implication of the law of the Mishnah, together with scriptural basis for that law.

7:3 II.1-8 Clarification of the implications of the law of the Mishnah on a topic that extends beyond the law at hand.

Nearly all speculation on the premises or principles of the law will turn out to commence with a particular Mishnah-paragraph and its concrete rule. Where we find speculative thought, it is nearly always precipitated by the character of a particular Mishnah-paragraph’s rule. What that means, so it seems to me, is that down to the conclusion of the Bavli, intellectual agenda of the law of Judaism found definition in the Mishnah and only there. No new topics, no new problems, no new abstract and theoretical inquiries, appear to have derived from any other source: the Mishnah dictated everything through the end of the Bavli.

Speculation on the law not in the context of Mishnah-commentary or amplification at all is exemplified by the asking of a question of theory that the explanation of the Mishnah does not require, and that the analysis of the law of the Mishnah may not even have precipitated. While speculative or abstract thought on law may involve the citation of a Mishnah-passage (very frequently, even the Mishnah-passage at hand), the speculative issue defines the cogent point that is under discussion, and that is what holds the discussion together. The composition (rarely a composite) can therefore have been composed without citation of the Mishnah-passage under discussion. Very frequently, compositions that st forth speculative or abstract thought on law, e.g., fabricated cases that permit us to identify operative principles and show how they work at interstitial situations, are subordinated to Mishnah-exegesis. But it is clear that, while depending upon a principle already established in connection with a statement in a Mishnah-paragraph, these abstract and speculative compositions, and the composites they comprise, should be read as distinct and free-standing. The reason is that the Mishnah-paragraph can have been adequately set forth without consideration of the speculative problem. So they are not essential to Mishnah-exegesis—even though, in context, the results of Mishnah-exegesis, which is to say, established principles of law, are essential to them. That is a somewhat subtle distinction, but it serves to allow us to identify and catalogue a distinct type of writing. A good example of such a speculative issue, which makes use of a Mishnah-passage but which holds together entirely within the framework of the issue at hand, is as follows:

1:1.I.3. A. Rami bar Hama raised the question, “What is the law as to a minor’s effecting a valid act of substitution?”

B. What circumstances are contemplated by this question? If we say that we deal with a minor who has not reached the age at which he may validly make a vow, then there should be no problem for you, since he cannot effect a consecration, shall I then maintain that he can effect a valid act of substitution?

C. Rather, when the question is raised, it concerns a minor who has reached the age of making vows. Do we maintain that since—a master has said, “[Scripture could have stated, ‘when a man shall take a vow of persons.’] Why does Scripture say, ‘If a man shall clearly take a vow . . .’? It serves to encompass a person who is not fully defined as to status, who is close to being a man,—indicating that an act of consecration on his part is valid, and, since he is capable of making a valid act of consecration, I should say that he also is able to make a valid act of substitution? Or perhaps, such a minor is not subject to sanctions, he also cannot get involved in making a valid act of exchange [for which a specific sanction is specified]?

D. And if you take the position that a minor can make a valid act of substitution, since he will eventually reach the status of being subject to the sanctions of the Torah, what is the law as to a gentile’s effecting a valid act of substitution? Should one say that, since he can validly effect an act of consecration,—since it has been taught on Tannaite authority, “A man, a man [of the house of Israel]” (Lev. 17:8)—why does Scripture repeat the word “a man”? It serves to encompass gentiles, who, consequently, take vows and pledge thank-offerings like an Israelite—so too I should say that gentiles also may make a valid act of consecration? Or perhaps, since gentiles never enter the category of those who are subject to sanctions, if a gentile should make an act of substitution, he has not effected the consecration of the substituted beast?

E. Said Raba, “Come and take note of a case. For it has been taught on Tannaite authority.”

F. “As to things declared holy by gentiles, people are not to derive secular benefit from those things, but the laws of sacrilege do not apply to them, and on account of the meat of such beasts, people are not liable for violating the laws of improper intention on the part of the officiating priest to eat his portion of the beast at the wrong time or in the wrong place, leaving over sacrificial meat beyond the proper time, and protecting the meat from cultic contamination. Gentiles also cannot effect a substitution, and they do not bring drink offerings, but drink-offerings are required with their offerings,” the words of R. Simeon.

G. R. Yosé said, “In all instances I prefer to impose the more strict rule.”

H. [The statement at F] pertains only to Holy Things that are designated for the altar, but as to Holy Things that are designated to the upkeep of the Temple house, the laws of sacrilege do apply.

I. [Raba continues,] “Now, in any event, the Tannaite authority has stated explicitly, “Gentiles also cannot effect a substitution.”

J. And [what does] Rami b. Hama [who asked the question to begin with, in the face of an explicit statement] on Tannaite authority [have to say for himself]?

K. “What I asked concerned the case not of a gentile who consecrated a beast for making atonement for himself, [since in such a case a gentile cannot effect a substitution, for he will never come into the category of sanctions], but rather, a case in which a gentile consecrated a beast so that an Israelite may gain atonement by the sacrifice? Do we adopt as our criterion the status of the person who makes the act of consecration [the gentile] or the person who is beneficiary of the atonement that the animal will effect [the Israelite]?”

L. Solve the problem by reference to what R. Abbuha said.

M. For R. Abbuha said R. Yohanan said, “He who consecrates [something for the Temple and then proposes to pay the value of the object and redeem it from the Temple] must add a fifth to the actual value of the object when he redeems it, and one for whom atonement is made is the one who can effect a valid act of substitution for the beast designated for his atonement, and one who designates a portion of the crop for the priestly ration out of his own [3A] grain in behalf of untithed grain belonging to someone else—the power of designating what priest gets the specified part of the crop belongs to him who did the act of separation.”

N. And Rami b. Hama [who here too faces an explicit answer long available to a question he thinks he has invented for the occasion]?

O. He will say to you, “In the case to which reference has just been made, the dedication was brought about by the act of an Israelite, so we follow the status of the one for whom atonement is made, and that is the case both at the beginning and at the end of the process [that is, the consecration of the animal, the sacrificing of the animal for atonement]. But here, this is what I am asking: do you impose the requirement that both the beginning and the end of the process of consecration and sacrifice long in the hand of the one who can validly effect an act of substitution or is that not the case? [It was a gentile who consecrated the beast, an Israelite who got the atoning benefit of the blood, so the exchange may or may not be holy.]”

P. That question stands.

The question is not required by the Mishnah-passage before us. To the contrary, it is abstract and can pertain to a variety of Mishnah-paragraphs.

A second example is called for, to distinguish between legal speculation in general and abstract theory on the law of a Mishnah-paragraph in particular. Here is a case in which the large issue—different rules governing in the period the Temple stood from the present age—transcends any one Mishnah-paragraph.

BAVLI TEMURAH 1:1F-O

F. Priests effect a substitution in the case of what belongs to them.

G. And Israelites effect a substitution in the case of what belongs to them,

H. Priests do not effect a substitution in the case either of a sin offering or of a guilt offering or of a firstling. [They own no share in sin- or guilt-offering prior to their being killed and their blood’s being tossed on the altar.]

I. Said R. Yohanan ben Nuri, “And on what account do they [the priests, who own firstlings] not effect a substitution in the case of a firstling?”

J. Said R. Aqiba, “A sin offering and a guilt offering are a gift to the priest, and a firstling is a gift to the priest.

K. “Just as, in the case of a sin offering and a guilt offering, they do not effect a substitution, so in the case of a firstling, they should not effect a substitution.”

L. Said to him R. Yohanan b. Nuri, “What difference does it make to me that one does not effect a substitution in the case of a sin offering and a guilt offering? For in case of these, they [the priests] have no claim while they [the beasts] are alive.

M. “Will you say the same in the case of the firstling, to which they [the priests] have a claim while [the firstling] is still alive?”

N. Said to him R. Aqiba, “But has it not already been stated, ‘Then both it and that for which it is changed shall be O. “At what point does sanctity descend on to it? In the house of the owner. So the substitute [becomes holy] in the house of the owner.”

I.1 A. There we have learned in the Mishnah:

B. As to the firstling, priests sell it when the animal is unblemished and alive, and when the animal is blemished, whether alive or slaughtered, and they give it as a token of betrothal to women [M. M.S. 1:2D-E].

C. Said R. Nahman said Rabbah bar Abbuha, “This teaching was repeated only in regard to this time [when the Temple lies in ruins], since the priest has a claim of ownership of the beast, but when the Temple stood, since an unblemished beast was for offering on the altar, they may not sell them when it is unblemished and alive.”

D. Raba objected to R. Nahman, “. . . priests sell it when the animal is unblemished and alive: when alive, yes, when slaughtered, no. When does that rule apply? Shall I say that it is in this age? Then is there now a beast that is unblemished and slaughtered [obviously not, since now the rule is that we wait until the beast suffers a blemish before slaughtering it, the alternative being to slaughter a valid animal as a sacrifice outside of the Temple, which is unthinkable]? So the phrase, priests sell it when the animal is unblemished and alive must pertain to the time in which the Temple stood. And it is then taught on Tannaite authority, priests sell it when the animal is unblemished and alive.

E. No. in point of fact the passage refers to the present age. Does it state, priests sell it when the animal is unblemished and alive—alive yes, slaughtered no? The very point of the passage is to inform us that in the present age too they sell the beast when the animal is unblemished and alive. [Miller: you might have thought that the priest has no claim on it until the firstling is blemished. But the point of the passage is not to indicate that we may not sell a slaughtered firstling; at the present time there is no unblemished slaughtered firstling.]

F. [8A] An objection was raised: with respect to a firstling it is stated, “But the firstling of a cow or the firstling of a sheep or the firstling of a goat you shall not redeem; they are holy; you shall sprinkle their blood upon the altar and shall burn their fat as an offering by fire, a pleasing odor to the Lord” (Num. 18:17). The implication is that it may be eaten [in its consecrated condition; it may not be sold in the market or weighed out in a secular fashion]. Now what are the circumstances to which reference is made here? Shall we say that it is at the present age? Then note the next clause of the passage: “you shall sprinkle their blood upon the altar and shall burn their fat as an offering by fire, a pleasing odor to the Lord” (Num. 18:17). In this age is there an altar? So it is self-evident that the passage refers to the age in which the Temple stood. And to what is reference made? Shall I say it is to a blemished firstling? Then once more let me point to the latter clause: “you shall sprinkle their blood upon the altar and shall burn their fat as an offering by fire, a pleasing odor to the Lord” (Num. 18:17). Now if we deal with a blemished firstling, is it going to be suitable for an offering? Rather, is it not with an unblemished offer, and it is taught, it may be sold. [So an unblemished firstling in Temple times may be sold, contrary to Nahman’s opinion.]

G. [But is the proposition that the two parts of the version before us must deal with an unblemished firstling?] The first clause [“you shall redeem”] speaks of a blemished animal, and the second of an unblemished one.

H. R. Mesharshayya objected, “A priest girl whose offspring was confused with the offspring of her slave girl—lo, these men eat heave offering; and they take and divide a single share at the threshing flood; [and they do not contract corpse uncleanness; and they do not get married, whether the woman is valid or invalid for marriage into the priesthood. If the confused sons grew up and reciprocally freed one another, they do marry wives suitable for marriage into the priesthood, and do not contract corpse uncleanness, and if they do, they do not incur forty stripes; and they do not eat heave offering, and if they eat it, they do not pay back to the priesthood the principal and the added fifth; and they do not take a portion at the threshing floor, but they sell heave offering, and the proceeds are theirs. And they do not take a share in the Holy Things of the sanctuary. And they do not give them Holy Things, but they do not take back their Holy Things that they gave to them. And they are free from the obligation to give the shoulder, cheeks, and maw to a priest.] And their firstling animal should be put out to pasture until it suffers a blemish. [And they apply to them the strict rules of the priesthood and the strict rules pertaining to ordinary Israelites] [M. Yebamot 11:5A-T]. Now with what situation do we deal here? If we say that it is with the present age [in which the priests’ firstling has to be blemished] before it can be slaughtered, then what difference is there between a firstling that belongs to us [who assuredly are priests] and one that belongs to them [who may or may not be priests], for those that belong to us also have to be blemished before they can be slaughtered and eaten? Rather, is it not the case that the passage addresses the age in which the Temple stood? Now if you take the position that the priest has a right of ownership in the body of the living firstling, that is well and good [and he may sell it alive and unblemished when the Temple stood. But if you say he has no right of ownership in the body of the live, unblemished firstling, then why not let the Temple treasurer come and take the animal? [If the priest has a claim, he can retain the firstling on the claim that perhaps he may be a priest and therefore has a prior claim and need not give the firstling to another priest, but he waits until it is blemished. But the Temple treasurer in the other case can give it to a genuine priest, since the priest has no claim on the firstling until it is brought to the altar. The upshot is that in Temple times the priest had a claim on an unblemished firstling, and here we deal with an unblemished animal; that contradicts Abbuha (Miller)].”

I. No, the passage speaks of the present age, and as to your question, “then what difference is there between a firstling that belongs to us [who assuredly are priests] and one that belongs to them [who may or may not be priests],” we give ours to a priest when it is blemished, but as to a firstling belong to them, since there is the possibility that one of them is a priest, priests cannot claim that firstling.

J. Another version of the matter: if we speak of the present age, then why raise as your case firstlings that belong to someone who may or may not be a priest? Even firstlings that belong to us, who are priests beyond doubt, are left to pasture until they are blemished! Rather, it is clear, the passage speaks of the age in which the Temple stood. And if we are dealing with a blemished firstling, why do we say that they are to be left to pasture until blemished? Are they not already blemished? So we deal with unblemished firstlings, and these [particular men] may not sell them; but persons who are certainly priests may sell them.

K. Indeed, we may address the case of firstlings at the present age. And as to your question, then why raise as your case firstlings that belong to someone who may or may not be a priest? Even firstlings that belong to us, who are priests beyond doubt, are left to pasture until they are blemished, we cannot disregard the priest [but have to hand over a firstling even though it is blemished], for there is no uncertainty that the priesthood is represented here [since it certainly is], but these men who may or may not be priests can put off any other priest, claiming, “I am a priest,” “I am a priest.”

L. An objection was raised: R. Simeon says, “ ‘You shall surely put the inhabitants of that city to the sword, destroying it utterly, all who are in it and its cattle, with the edge of the sword. You shall gather all its spoil into the midst of its open square and burn the city and all its spoil with fire, as a whole burnt offering to the Lord your God’ (Dt. 13:15-16). ‘. . . its cattle:’ excluding the firstling beast and an animal designated as tithe in the apostate city; ‘. . . its spoil:’ excluding the money designated as second tithe that is in it.” Now with what situation do we deal here? If we say that it is in the present age, then at this time does the law governing the apostate city pertain? And have we not learned: “The law governing the apostate city applies only when the court of seventy-one members is in session”? So it is obvious that we deal with the time at which the Temple was standing. And in what regard? Should we say, with a blemished firstling, then that falls into the category of “its cattle,” so it is obvious that we deal with an unblemished firstling. Now if you take the position that the priest has a right of ownership in the beast, then there is no problem, but if you take the view that the priest has no right of ownership in the beast, then why draw proof from a reference to “its cattle,” when you can prove the same point from “ ‘its spoil’—and not the spoil that belongs to Heaven”?

M. No, we deal with a blemished beast, and, as to your question, “then that falls into the category of ‘its cattle,’ ” the sense of that phrase is, “whatever is eaten in the category of “its cattle,” which would exclude the classifications of beast as firstlings and animals that have been designated as tithe, for these do not fall into the class of “its cattle.” For we have learned in the Mishnah: All invalidated Holy Things after they have been redeemed are sold in the marketplace and are slaughtered in the marketplace and are weighed by the pound except for the blemished firstling and tithe of cattle. For the advantage of selling them in the market, where demand is higher, would fall to the owner. Invalidated Holy Things—their advantage falls to the sanctuary. But they weigh a maneh against a maneh in the case of the meat of the firstling [M. Bekh. 5:1A-G].

N. An objection was raised from the following dispute:

O. “ ‘If any one sins and commits a breach of faith against the Lord’ (Lev. 5:21/6:2)—this encompasses Lesser Holy Things, which are the property of their owner,” the words of R. Yosé the Galilean.

O. Ben Azzai says, “It serves to encompass peace-offerings.”

P. Abba Yosé b. Dosai says, “Ben Azzai referred only to the firstling alone.”

Q. Now with what situation do we deal? If we say that it is in the present age, lo, the case of the firstling is then compared with peace offerings [of which there is none these days]. Rather, it is obvious, we speak with the age in which the Temple stood. And with what do we deal? If we say that it is with a blemished animal, lo, it is comparable once more to peace-offerings, so do we not deal with the unblemished beast? And the passage then infers that the priest has rights of ownership in the body of the unblemished firstling!

R. [8B] Said Abayye, “In point of fact we deal with an unblemished beast, but it is a firstling located overseas, and the passage represents the opinion of R. Simeon, who has said, ‘If unblemished firstlings are brought from overseas, they may be offered upon n the altar.’ ”

S. An objection was raised: Said to him R. Yohanan b. Nuri, “What difference does it make to me that one does not effect a substitution in the case of a sin offering and a guilt offering? For in case of these, they [the priests] have no claim while they [the beasts] are alive. Will you say the same in the case of the firstling, to which they [the priests] have a claim while [the firstling] is still alive?” Now with what situation do we deal? If we say that it is with a blemished firstling, lo it is compared to a sin-offering and a guilt offering, so is it not an unblemished firstling? And yet the Tannaite authority states, to which they [the priests] have a claim while [the firstling] is still alive! [That explicitly rejects Abbuha’s view].

T. Said Rabina, “In point of fact we once again deal with an unblemished beast, but it is a firstling located overseas, and the passage represents the opinion of R. Simeon, who has said, ‘If unblemished firstlings are brought from overseas, they may be offered upon the altar.’ ”

U. Shall we say that there is a Tannaite dispute on the same matter [as in the following:]

V. A valid act of substitution can be made with a firstling that is located in the house of the owner, but with one that is located in the house of a priest a valid act of substitution cannot be effected.

W. R. Simeon b. Eleazar says, “Once the firstling has reached the domain of the priest, a valid act of substitution cannot be effected.”

X. Now that is the position of the initial authority [which is unthinkable, so we have to explain that] in this case at issue is the following: the initial Tannaite authority takes the view that in the house of the priest the priest has the power to make an act of substitution, but the owner has not got the power to effect a valid act of substitution, which yields the principle that the priest does have rights of ownership in the body of the firstling!

Y. There is no contradiction to be drawn from this dispute for the position at hand, for at issue is the same point that is at issue between R. Yohanan b. Nuri and R. Aqiba. The initial Tanna concurs with R. Yohanan b. Nuri, and R. Simeon agrees with R. Aqiba [that although the priest has a claim on the firstling when it is alive, he still cannot effect an exchange, as we infer from an analogy (Miller)].

At issue is a theoretical problem that encompasses our Mishnah-paragraph and a variety of others. Abstract legal theorizing in general, not tied up in any close way to a particular law of the Mishnah but formulated entirely within a broader theoretical and speculative framework, on the other, is nicely exemplified by this entry.

Here is the catalogue of such compositions and composites in the tractate under study.

1:1.I.3-20

1.1F-O.I.1-3

1:2H-J.I.3-6 Drawn in the wake of Mishnah-exegesis is a marvelous speculative essay on the interplay of different classifications of sanctification.

1:3.I.1 Affect of an act of consecration on fetuses. This is invited by the Mishnah-paragraph but hardly essential for the exegesis of the Mishnah’s statement itself. It falls into the category of not theorizing on the basis of the Mishnah’s law but theory for its own sake.

1:3.II.5-9

3:5 I.1 A speculative question not required for Mishnah-exegesis or even precipitated by the Mishnah is raised here. The intersection with the Mishnah is only topical.

4:1.I.3-6 Abstract, theoretical problem that draws upon the Mishnah-paragraph in pursuit of a free-standing issue. This entire composition has been formulated as an amplification of our Mishnah-paragraph by reference to the theory implicit therein, and must be deemed entirely cogent and admirably crafted, even though by the end we have moved very far from the concerns of our Mishnah-paragraph.

5:4 I.3-4 Deductions to be drawn from a deduction based on the rule of the Mishnah. This stands autonomous of the Mishnah. It is noteworthy that this composition follows Mishnah-exegesis.

A composition or composite built upon a verse or a set of verses of Scripture will ordinarily ask of that passage of Scripture a set of exegetical or speculative questions, such as we find formed with reference to the Mishnah. Such a composition (rarely a composite) can have been put together entirely without reference to the Mishnah-paragraph at hand; it holds together by appeal to the verse or verses of Scripture that are subjected to analysis. Where an even-sizable composition focused upon Scripture in fact responds to the Mishnah’s paragraph’s law, e.g., proving such a law by appeal to Scripture, I treat that composition or composite as subordinate to Mishnah-exegesis. Catalogued here are only those compositions or composites that cannot have been held together without the scriptural mainframe. Here is an example of such a composition in our tractate:

20. A. The master has said, “If it is that one should not slaughter such beasts, lo, that has already been stated elsewhere.” Where has that been stated?

B. It is in line with that which has been stated on Tannaite authority:

C. “Blind or broken or maimed you shall not offer unto the Lord” (Lev. 22:22) —

D. What is the sense of Scripture here? If it is that such animals are not to be consecrated to begin with, lo, this has already been stated earlier [at Lev. 22:20].

E. Then what is the meaning of Scripture when it says, “you shall not offer unto the Lord” (Lev. 22:22)? It means you shall not slaughter such a beast as a sacrifice.

F. “nor make an offering of them” [meaning, of blemished animals for the altar, Lev. 22:20]—this refers to offerings made by fire on the altar.

G. I know only that that is the rule for the whole of the beast. How do I know the rule for only part of the beast? Scripture says, “of them.”

H. How do I know the rule covering the sprinkling of the blood [of blemished animals}?

I. Scripture states, “on the altar.”

J. “Unto the Lord” serves to encompass the case of the scapegoat. [One who consecrates a blemished beast to serve as scapegoat violates the prohibition at hand.]

K. And does “unto the Lord” include something more?

L. And has it not been taught on Tannaite authority:

M. If you provide an exegesis for the word “offering,” shall I understand the word to encompass the case of animals consecrated for the upkeep of the Temple house, for these are subsumed under the classification of “offering,” when for example Scripture states, “We have therefore brought the offering of the Lord” Num. 31:50)?

N. The verse states, “and has not brought it to the door of the tent of meeting” (Lev. 17:4), and that means, that which is suitable to be brought to the door of the tent of meeting is that on account of which people are liable on the count of slaughtering holy things outside of the designated place, and that which is not suitable to be brought to the door of the tent of meeting is that on account of which people are not liable on the count of slaughtering holy things outside of the designated place. Then shall I exclude these, but not the red cow that is burned for the making of purification-water, and the goat that is sent forth, for these are suitable to be brought to the door of the tent of meeting? Scripture says, “for the Lord,” meaning, that which is in particular for the Lord, excluding these, which are not particularly designated for the Lord.”

O. Said Raba, “In the one passage we follow the sense of the context. Since the verse concerning slaughtering outside the Temple court, ‘to the door of the tent of meeting’ serves to encompass [all unblemished animals, slaughtering any of which outside brings sanction], so the text ‘unto the Lord’ in that connection excludes [the cases of the scapegoat and the red cow, and these are to be slaughtered outside of the temple]. Here, the verse, ‘by fire,’ excludes [only in respect to an offering that is burned is there liability for dedicating a blemished animal, but an offering that is not burned but dedicated in its blemished state will not bring in its wake a sanction. But what about the scapegoat?] [As to the scapegoat], ‘unto the Lord’ used in that connection excludes [the scapegoat; if one dedicates it in its blemished condition he violates the law, ‘You shall not offer . . .].”

P. So the reason that the blemished animal may not be brought is that Scripture says, “unto the Lord.” But if Scripture had not covered that case by the specific statement, “unto the Lord,” I might have concluded that it is permitted to present a blemished animal as a scapegoat. But take note: it is only casting the lot that designates the beast that is fit to be offered for the Lord. [For the rite of the Day of Atonement, two animals must be available, and these must be unblemished. The reason is that at the outset we do not know which one will be the scapegoat “for Azazel,” so both must be suitable “for the Lord.” Only the casting of the lot determines the classification of the beast. That reason, and not Scripture, should have sufficed.]

Q. Said R. Joseph, “Whom does this exegesis represent? It is Hanan the Egyptian, who has said, ‘Even if there was already blood in the cup [deriving from the goat designated for the Lord, the goat having been slaughtered, but the blood had not yet been tossed on the altar, and the scapegoat was lost or blemished,] one still can bring another goat [for a scapegoat] to pair with [the goat that has been slaughtered, and that is done without casting lots, since the animal for the Lord has already been slaughtered.]”

R. Granted that one can assign such a view to Hanan the Egyptian, who holds that there can be no rejection [even though the goat for the Lord has already been slaughtered, we can select another animal for the scapegoat. But the contrary position is that the blood is discarded, since the rite has been interrupted], does that mean that it is not necessary to cast lots? Perhaps he brings another set of goats and casts lots?

S. Rather, said R. Joseph, “Whom does this exegesis represent? It is R. Simeon. For it has been taught on Tannaite authority as follows:”

T. If one of the goats died, one brings the other without casting lots [Miller: I might have thought since lots are not required, there is no need that the scapegoat should be unblemished. The verse, ‘unto the Lord’ teaches us that that is not so].”

U. Raba said, “The verse, ‘unto the Lord,’ is required only to cover the case in which the scapegoat became blemished on that day [after the lots had been cast], and one had redeemed the beast for another animal. [7A] You might have thought that to begin with, we do not know which one of them is going to be designated ‘for the Lord,’ while here, since the animal that is designated ‘for the Lord’ has already been discerned, there is no question of a flogging [for violating the law, ‘you shall not offer,’ if the scapegoat is dedicated in a blemished condition]. The words, ‘for the Lord’ tells us that that is not the case [and even here there is a penalty for violating the law and bringing a blemished beast].”

21. A. A master has said, “In the name of R. Yosé b. R. Judah they have said, “Also one transgresses on the count of not receiving its blood” [T. Tem. 1:10],

B. What is the scriptural basis for the position of R. Yosé b. R. Judah?

C. Scripture states, “That which has its stones bruised or crushed or torn or cut . . . you shall not offer to the Lord” (Lev. 22:24).

D. This refers to the receiving of the blood, concerning which R. Yosé b. R. Judah spoke.

E. And as to the initial authority [who does not concur in his view], how do we account for the repeated language, “you shall not offer to the Lord”?

F. He requires that language to cover the matter of sprinkling the blood of a blemished animal [indicating that that is punishable].

G. But does that point not derive from the language, “upon the altar.”

H. That is simply the manner in which Scripture formulates its ideas [Miller: summing up the law relating to blemishes, and we do not infer a particular ruling from that language].

I. And as to R. Yosé b. R. Judah, is this not also to be treated as simply the manner in which Scripture formulates its ideas?

J. Indeed so.

K. Then how does he know that sprinkling the blood of a blemished animal also involves the violation of a prohibition?

L. He derives that fact from the following verse of Scripture: “Neither from the hand of a foreigner shall you offer” (Lev. 22:25). This refers to the receiving of the blood, concerning which R. Yosé b. R. Judah spoke.

M. And as to the initial authority [who does not concur in his view], how do we account for “Neither from the hand of a foreigner shall you offer” (Lev. 22:25)?

N. He requires it to make the following point: you might have thought that since the children of Noah were commanded only concerning the matter of the loss of a limb [which is the only defect that will disqualify a beast for sacrifice upon altars of gentiles, but mere blemishes will not disqualify animals for their altars], there would be no difference between an animal offered by them on their altar and one offered by them on ours. So we are informed that that is not the case.

O. There is another version, as follows:

P. “In the name of R. Yosé b. R. Judah they have said, “Also one transgresses on the count of not receiving its blood” [T. Tern. 1:10].

Q. What is the scriptural basis for the position of R. Yosé b. R. Judah?

R. Scripture states, “That which has its stones bruised or crushed or torn or cut . . . you shall not offer to the Lord” (Lev. 22:24).

S. This refers to receiving the blood, and as to not sprinkling the blood, that rule derives from the words, “upon the altar.”

T. And as to rabbis, should they not derive the rule governing not sprinkling the blood from the words, “upon the altar””

U. Indeed so.

V. Then for what purpose does Scripture state, “That which has its stones bruised or crushed or torn or cut . . . you shall not offer to the Lord” (Lev. 22:24)?

W. It is required to give us the rule covering the high place of an individual [indicating that one may not offer on a high place of an individual a blemished animal].

X. And from the perspective of R. Yosé b. R. Judah, is this same verse not required to cover the high place of an individual?

Y. Indeed so!

Z. Then how does he know the rule that it is prohibited to receive the blood of a blemished animal?

AA. He derives that fact from the following verse of Scripture: “Neither from the hand of a foreigner shall you offer” (Lev. 22:25). This refers to the receiving of the blood, [concerning which R. Yosé b. R. Judah spoke.]

BB. And rabbis required that verse for a different purpose. It might have entered your mind to suppose that since the children of Noah were commanded only concerning the matter of the loss of a limb [which is the only defect that will disqualify a beast for sacrifice upon altars of gentiles, but mere blemishes will not disqualify animals for their altars], there would be no difference between an animal offered by them on their altar and one offered by them on ours. So we are informed by the language “of any of these” that that is not the case.

I give both No. 20 and also No. 21 to show the difference between a composition that is built on the exegesis of a verse of Scripture and one that draws upon a verse of Scripture but does not rest upon such a verse. No. 20 works on the meaning of several verses and explains what meaning is to be derived from those verses. The composition holds together by appeal to the verses under discussion; without those verses, we have nothing. No. 21, by contrast, appeals to Scripture for a foundation for a rule in the Mishnah, but it is the rule of the Mishnah that forms the centerpiece of the discussion. The following compositions or large-scale composites depend upon verses of Scripture to provide the organizing principle of cogency:

2:1.III.3 (tacked on)

2:2.II.8-13+14-16 (Part of a composite)

In general, I find only a modest number of composites that appeal for cogency to not the Mishnah but Scripture. But we shall presently see another type of composite, one that is formed around a given theme or topic, and many of these topics derive from Scripture.

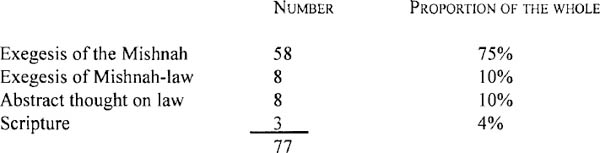

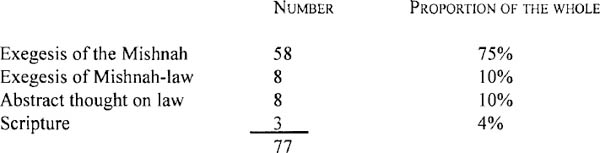

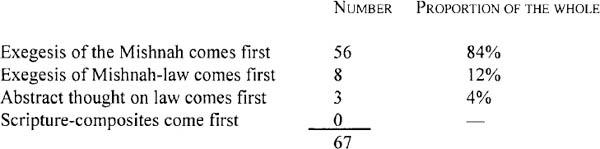

How are the several types of forms ordered? Mishnah-exegesis comes first, abstract legal speculation, last. (Mishnah-exegesis includes inquiry into the scriptural foundations for the Mishnah’s rule.) Since the obvious hypothesis is that Mishnah-exegesis takes priority over abstract legal theorizing, we shall begin with a list of the large-scale composites, treating a given paragraph of the Mishnah, in which the exegesis of the Mishnah comes first, then those in which the exegesis of the Mishnah’s law takes priority, then those in which the discussion of abstract law comes first, finally those in which Scripture-exegesis supplies the principle of cogency and the purpose of inquiry. In the second, third, and fourth instances, we shall further point to cases in which Mishnah-exegesis is included second or third or even fourth in order. Where a second major composite follows an introductory item, e.g., Mishnah-exegesis followed by exegesis of the Mishnah’s law, abstract legal theorizing, then Scripture-exegesis as a free-standing entry, I specify the sequence. Where the introductory item predominates and no other type of discourse proves paramount, or none follows, I do not consider the unfolding of a composite.

1. MISHNAH-EXEGESIS COMES FIRST, OFTEN-TIMES FOLLOWED BY EXEGESIS OF THE MISHNAH’S LAW

1:1A-E.I.1-21

1:2A-G.I.1-4 (Scriptural basis for Mishnah’s rule)

1:2H-J.I.1-6 (First comes scriptural basis for the Mishnah, then abstract speculation.)

1:4-5.I.1, II.1, III.1, IV.1, V.1, VI.1 Who is the Tannaite authority behind the rule?

1:4-5.VII.1, VIII.1, IX. 1: Scriptural basis

1:6.I.1, 2 Scriptural basis for the Mishnah’s rule.

1:6.II.1-3 As above.

2:1.I.1

2:1.II.1

2:1.III.1-2(+3: scriptural composition tacked on)

2:2.I.1

2:2.II-III

3:1A-E.I.1-10

3:1F-N.I.1, II.1, III.1

3:2A-D I.1

3:3G-N, 3:4 I.1-3

3:5.II.1

4:1 I.1-2+3 Explanation of the formulation of the Mishnah’s rule. This is followed, 4:1.1.3-6, by an abstract, theoretical problem that draws upon the Mishnah-paragraph in pursuit of a free-standing issue.

4:2-4 I.1+2-7

4:2-4 II.1

5:1-2.II.1

5:1-2.III.1, IV.1, 2

5:3 II. 1

5:4 I.1-2

5:5 I.1-2

5:6 I.1

5:6 II.1

6:1 I.1-2

6:1 I.3

6:1 I.4-6+7