Internal Struggles

The newspapermen who reported so glowingly on the state of CHP Academy training in the wake of Newhall were particularly taken by CHP Sgt. Ron Von Rajcs, an influential staff instructor at the academy known colloquially by the cadets as “The Red Baron.” Sgt. Von Rajcs, the lead instructor for the Academy’s “Enforcement Tactics” class, dutifully explained to the reporters that the class was “the most important course at the Academy,” because “it wraps up all the theory they have studied in books in the classroom. It’s taken in their final month and is the course that actually teaches them to go out and to their job.”3

While Sgt. Von Rajcs was eager to promote the benefits of the 36-hour class to the reporters and to emphasize the importance of the survival skills it taught the officers, there was much more to the story that wasn’t fit for public consumption. It was important for the department, and the Academy in particular, to salvage its dignity and reputation in the wake of the Newhall disaster, and airing its dirty laundry in front of a press that was often uncomplimentary to the department was not the path to accomplishing that goal.4 Therefore, Sgt. Von Rajcs was left to explain how there were many possible explanations for the tragic shooting that were unrelated to the quality of training received at the academy, to wit: “Sometimes an officer gets to thinking that nothing can happen to him,” and, “sometimes he gets careless.”5

What Sgt. Von Rajcs couldn’t tell the press is that, while the CHP academy was indeed “one of the finest law enforcement training schools in the world,” certain elements of the curriculum were suffering as a result of time budgets and internal political struggles at the Academy, including his vaunted “Enforcement Tactics” class.6

It’s axiomatic within institutions of higher learning that every instructor believes his subject is the most important and deserves greater attention. It’s also true that there is never enough time to cover all the required subjects to the desired depth. Thus, Sgt. Von Rajcs found himself in a position familiar to anybody who has been a teacher—he simply didn’t have enough time to teach his busy cadets what he wanted them to know—and what he wanted them to know was critical to their survival.

In a 900-hour, 16-week schedule crowded with 70-plus subjects, Sgt. Von Rajcs was allocated just 36 hours for his Enforcement Tactics class, which, at its core, was a class devoted to the tactics of felony car stops.7 Of those hours, 30 were classroom hours and only six were practical, hands-on “field exercises” in which the cadets had the opportunity to integrate and apply the lessons from all the subjects taught in the previous three months.8 When asked by an incredulous reporter if six hours was enough time to devote to this critical work, Sgt. Von Rajcs could only answer that “We give them about as much as they can absorb,” an answer that he surely found as unsatisfactory as the reporter did.9

What made this an especially bitter pill for Sgt. Von Rajcs and staff was the knowledge that they had personally been fighting an internal battle with the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) for control of the curriculum for the past five years, and valuable training hours had been wasted in the process.

Under Director J. Edgar Hoover, the FBI had established a presence at the CHP Academy and installed several guest instructors on the faculty in a move that was seen as mutually beneficial to both agencies. The FBI earned as much prestige as it gave via its association with the CHP, which even at this early date had established a strong reputation among law enforcement agencies.

Unfortunately, the FBI’s estimation of its subject matter expertise often exceeded that of the Patrol’s, which felt that some of the FBI techniques and procedures were ineffective and unsuitable for their officers. This situation had come to a head a few years earlier, when Sgt. Von Rajcs’ boss, Physical Training Supervisor Sgt. George Nuttall, had convinced the CHP Commissioner after a six-month fight to replace an FBI-developed curriculum of baton and arrest method training with a more effective one developed by an officer at a rival agency. The adoption of Los Angeles Police Officer Bob Koga’s baton and “Twistlock” control methods in lieu of the FBI’s baton and come-along techniques was a significant blow to the prideful FBI, which immediately recalled the lead FBI instructor at the CHP Academy who had “allowed” this to pass.

The FBI sent a replacement to the CHP Academy, and he was tasked with teaching the one remaining FBI class of “Techniques of Arrest.” This instructor, nearing retirement, was clearly unmotivated and did not embrace his new job with fervor. In Sgt. Nuttall’s and (soon to be Sgt.) Von Rajc’s opinion, the FBI agent’s poor instructional technique and lack of commitment to teaching these critical, high-risk skills for placing people in custody resulted in “nothing but a dog and pony show” that wasted valuable teaching time, encouraged sloppy techniques, and would eventually get someone hurt. After Sgt. Nuttall’s tour of duty expired and Sgt. Von Rajcs took the helm as Physical Training Supervisor, he eventually completed Sgt. Nuttall’s vision of eliminating the FBI’s direct involvement in this area of CHP training entirely.10

In the short term however, Sgt. Von Rajcs and his fellow Enforcement Tactics instructors were left in the unenviable position of having to simultaneously teach their cadets lots of new material essential to their survival, and also correct the bad habits they had learned in the FBI-led Techniques of Arrest course, all in an incredibly compressed timeframe that included a mere six hours of hands-on field work.

The techniques taught in the Enforcement Tactics class compared favorably to those taught in agencies and academies throughout the world. Indeed, the CHP had a reputation for being on the leading edge of training at the time, and the skills modeled by Sgt. Von Rajcs and staff were probably state of the art for the era. Under the spotlight of evaluation that followed the Newhall shooting, deficiencies would be identified and improvements would be incorporated, but it appears that the critical limitation was not the quality of the information imparted, but rather the limited time allocated to ingrain the desired good habits.

Cadets Gore, Frago, Pence, and Alleyn managed to survive the intensity of the Red Baron’s course, but under the glow of the neon lights from the Standard station at the corner of Henry Mayo Drive and The Old Road, they confirmed the fears of Sgts. Nuttall and Von Rajcs that, while the academy could afford to spend 22 hours of the curriculum on “Basic Reports” and six hours on the “History and Geography of California,” a half-assed 17-hour course on arrest techniques and six hours of field work dedicated to high-risk car stops just wasn’t enough.

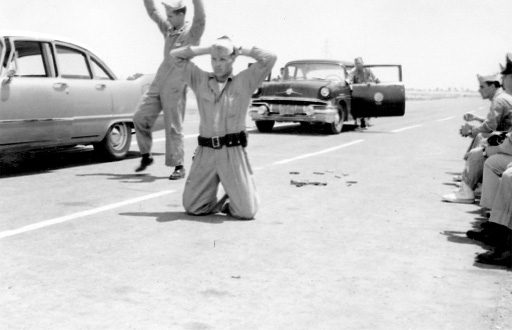

Academy cadets observe as Enforcement Tactics instructors (in street clothes) demonstrate 1950s-1960s era “Hot Stop” procedures, using two of their CTC I’ 59 classmates (in coveralls) as “suspect” role players. In the top picture, the standing suspect has just been directed out of the vehicle and is kicking the door shut with his foot, as instructed by officers behind the doors of the patrol car to the rear. In the middle picture, the officers have left their cover positions to move forward and place the suspects in custody. In the bottom photo, the instructors and cadets have switched roles, and the instructors are now the suspects. Note the revolver in the front breast pocket of the suspect in right foreground--a dangerous surprise and valuable lesson for the young officer in training. Photos courtesy of the California Highway Patrol Museum.