Growing Pains

In 1966, California was a rapidly growing state with a bright future. The road to that future was packed by an ever-increasing number of cars and trucks, and the resources of the CHP were stretched thin in an attempt to police all those golden highways and the state’s rapidly expanding, adolescent freeway system.

That same year, the voters of California elected Ronald Reagan as Governor in a landslide election over Edmund G. “Pat” Brown. Reagan had campaigned as a tough “law and order” candidate who vowed to crack down on the growing trend of violent anti-war and anti-establishment protests and riots that were gripping the state in places like the University of California, Berkeley campus.24

Reagan found an ally in the “Father of the Freeways,” state Sen. Randolph Collier, whose 1947 Collier-Burns Act gave birth to the California Highway Plan and resulted in the most significant post-war freeway construction program in the nation.25 Together, they pushed for a rapid expansion of the CHP to meet the state’s growing commitments on the highways and freeways, man a new statewide vehicle inspection program, and prepare a reaction force capable of handling “large-scale civil disobedience” like that seen in Berkeley and other places in the turbulent era.26

Senator Collier’s S.B.317 provided for a doubling of the Highway Patrol in three short years—a phenomenal growth curve that would bring the Patrol’s end strength up to about 6,000 officers between 1966 and 1970.27

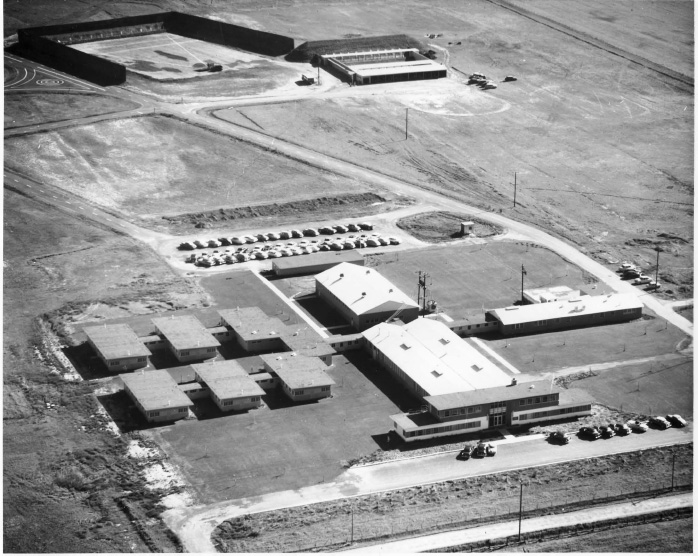

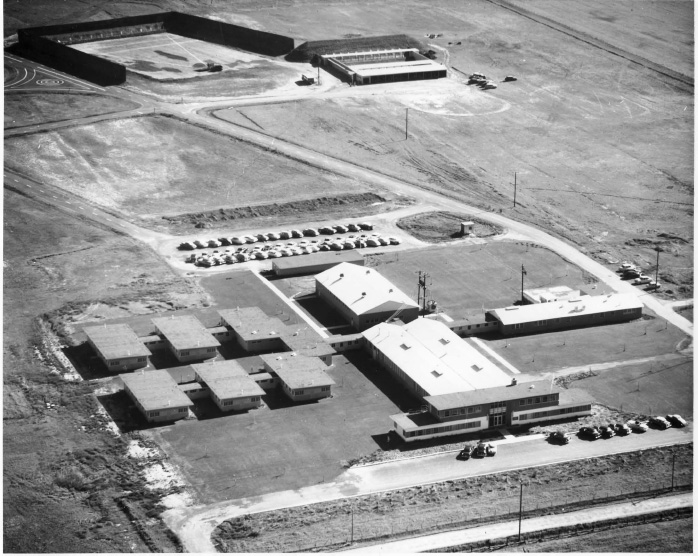

The CHP academy on Meadowview Road, built in 1953 to house and train 80 cadets at a time, began a corresponding expansion project in 1965 to meet the demand. The cadet dorms were expanded to accommodate 360 cadets, five new classrooms, and 10 new offices were added, and a new mess hall was constructed, as well.28 The improvements allowed the CHP to run three simultaneous classes of 120 men each on a staggered basis, so that a week after one class graduated, another began.29 Officers Alleyn (who reported to the academy in April of 1968, Class III-68), Frago, and Gore (classmates in Class V-68, August 1968), and Pence (Class I-69, January 1969) were all products of this high-production machine.

An aerial view, Circa 1955, of the new Meadowview CHP Academy (used 1953-1976). At top left is the outdoor firing range, and at top center is the “indoor” (covered) firing range. This small facility would go through an aggressive expansion project in the mid-1960s to accommodate a surge in hiring. Photo courtesy of the California Highway Patrol Museum.

While the CHP’s rapid expansion was critical to the welfare and development of the state and an impressive institutional accomplishment, it did not come without hazards. There was a concern among some veteran officers that the quality of training was slipping in the rush to grow the Patrol. Crowded facilities at the academy caused by a spike in the number of students were a concern, and so was the quality of the probationary, “on the job” training that newly minted officers received after reporting for their first assignment.30

Field Training Officers (FTOs) are typically mid- to senior level officers with a wealth of experience, maturity, and judgment that make them ideally suited to mentoring young officers fresh from the Academy who are full of book sense, but not street sense. The CHP, like other agencies, would pair up the young rookies with FTOs who would help them make the jump from the largely sterile, black-and-white academic environment of the Academy to the gritty, vague, and dynamic environment of the real world. Under the tutelage of a seasoned FTO, the young officer would quickly learn the path to success, efficiency, and survival in the field.31

The process was short-circuited by the department’s rapid growth from 1966 to1970, however, because there was a critical shortage of experienced officers to serve as FTOs and stand watch over the new charges as they learned to spread their wings. The CHP found itself in the unenviable position of having its rookies negotiate their way through the break-in period under the guidance of officers who were still rookies themselves, especially in junior-manned offices that lacked seniority, like Newhall.32 As each batch of new officers arrived fresh from the Academy, they began taking their cues from officers who were barely ahead of them on the learning curve, a process that was just as unfair to the trainers as it was to the trainees.

The logistics of the situation also dictated that the young officers fresh off of break-in training would be unlikely to get assigned to a senior partner that might further their training. The few veteran officers to be found were typically working the more desirable day and afternoon shifts, which their seniority allowed them. Day shift (“A Watch,” 05:45-14:15) and afternoon shift (“B Watch,” 13:45-22:15) cars were usually manned by a single officer, in contrast to the evening “graveyard” (“D Watch,” 21:45-06:15) cars, which were manned by two officers. Thus, junior officers typically wound up working with each other on the graveyard shift with few experienced mentors to learn from.33

This pattern was certainly the rule in the junior Newhall office of 1968 to 1969. On the night of the shooting, Officers Gore and Frago were just 16 months out of the Academy, Officer Alleyn just four months senior to them, and Officer Pence had but 12 months experience. Their training officers were hardly more experienced. Officers Gore and Frago were trained by break-in officers who had less than one year experience at the time.34 Officer Pence was trained by Officer Harry Ingold (Unit 78-19R—the driver of the fourth car on scene at the shooting), who was only slightly more seasoned with about two years experience on the job at the time he took Officer Pence under his wing. Officer Ingold would later wryly remark, at a seminar hosted on the thirty-ninth anniversary of the shooting, that, “Back then, we [Ingold and partner Roger Palmer] … thought we knew everything there was to know.”35

Indeed, with just three years experience on the night of the Newhall shooting, Ingold, a salty vet by comparison, hadn’t even put in enough time to qualify for his first “hashmark” on his uniform sleeve (awarded upon completion of five years of service).

In contrast, Twining had been committing felonies since age 13 (21 years) and had earned a PhD in violence in nine federal prisons. He had killed at least two men and had spent only 16 months outside of prison since his adolescence.36 Davis had entered the Marine Corps to avoid an “assault with a deadly weapon” charge and had killed his first man, a fellow Marine, at age 19. By age 21, he was in federal prison for a series of bank robberies, where he remained until a little less than nine months before the night Officers Gore and Frago pulled him over in Newhall.37