The “Brahms Fog”: On Analyzing

Brahmsian Influences at the Fin de Siècle

WALTER FRISCH

In a letter written in April 1894 to his friend Adalbert Lindner, the twenty-one-year-old Max Reger staunchly defended Brahms against his opponents. Although the music may at first be difficult to grasp, Reger noted, “Brahms has nevertheless come so far that all truly intelligent and sensitive musicians, unless they want to make fools of themselves, must acknowledge him as the greatest of living composers.” Reger continued: “Even if Lessmann takes such pains to destroy Brahms and the Brahms fog (to use Tappert’s term), the Brahms fog will survive. And I much prefer it to the white heat of Wagner and Strauss.”1

Reger refers here to Otto Lessmann, editor of the Allgemeine Musik-Zeitung in Berlin from 1881 to 1907, and to Wilhelm Tappert, a prominent critic of Wagnerian sympathies. I have not located where Tappert coined the term “Brahms fog,” or Brahmsnebel. Nor is it exactly clear what he, or Reger quoting him, meant by it. But the image is certainly an evocative one: the music of Brahms is seen as generating or being enveloped in a thick, dark mist; from the opposite camp comes the fiery glow of chromaticism and program music.

It is well known that during the last quarter of the nineteenth century much of Austro-German music was polarized between the Brahmsians and the Wagnerians, between the fog and the white heat. Most scholars and performers have been attracted more readily to the brighter glow, to the phenomenon of Wagnerism in European music. There has been less appreciation of how widely, and in what ways, Brahms’s influence extended over the world of lieder and piano and chamber music.

“Brahms is everywhere,” remarked Walter Niemann in an article of 1912.2 Niemann, a devoted follower of Brahms (later to become his biographer), went on to survey briefly no fewer than fifty European composers whose piano music he said bore the unmistakable traces of the master’s influence. Writing in 1922, Hugo Leichtentritt observed similarly that “from about 1880 all chamber music in Germany is in some way indebted to Brahms.”3 The same could be said of many of the thousands of lieder issued from the German publishing houses in the decades around 1900.4

There is no question that the Brahms idiom had tremendous prestige in these repertories. For one thing, as Niemann noted, some external elements of the style—the thick piano figuration, the rhythmic devices (two-against-three), the characteristic textures—were easily imitated. Indeed, to do so was apparently a point of pride among young composers. Alexander Zemlinsky, one of the most talented pupils at the Vienna Conservatory in the early 1890s (when the teaching staff was composed of such Brahms cronies as Robert Fuchs, Julius Epstein, and Anton Door), remarked in later years that “it was considered especially praiseworthy to compose in as ‘Brahmsian’ a manner as possible.”5 In 1893 the young Reger could actually boast to Lindner, “The other day a personal friend of Brahms mistook the theme from the finale of my second violin sonata [op. 3] for a theme from one of Brahms’s recent works. Even Riemann [Reger’s teacher] told me that I know Brahms really through and through.” Reger went on to say, “Brahms is the only composer of our time—I mean among living composers—from whom one can learn something.”6 Reger’s latter point is significant: Brahms represented, until his death in 1897, the most powerful and most respectable living model for younger German composers.

Just as one cannot easily measure the extent or scope of a fog, so would it be impossible and frustrating to tally all the composers who from the 1880s on fell under the sway of the Brahms idiom. (Some sense of the thickness of the fog can be gleaned by the number of musical works dedicated to Brahms. See Part IV of the present volume.) Even beyond any direct impact on musical style and technique—on the way music sounds—Brahms may have had a still farther-reaching effect on the whole concept of serious concert music in the twentieth century. Such, at least, is the provocative argument of J. Peter Burkholder, who suggests that with his self-conscious and complex historicism Brahms was seeking a place beside Bach and Beethoven in the “museum” of great music. Burkholder suggests that this attitude toward composition—in which one writes music chiefly to assure one’s place in history—lies at the basis of musical modernism and has carried over into the present century.7

What I would like to trace in this essay is something more modest than Burkholder’s bold picture: a vignette of some of the technical and expressive ways in which Brahms’s music was appropriated by three of the most talented younger Austro-German composers coming to maturity in the 1890s: Alexander Zemlinsky, Arnold Schoenberg, and Max Reger. Even with such a restricted field, a comprehensive study of the phenomenon of Brahms’s influence is not possible.8

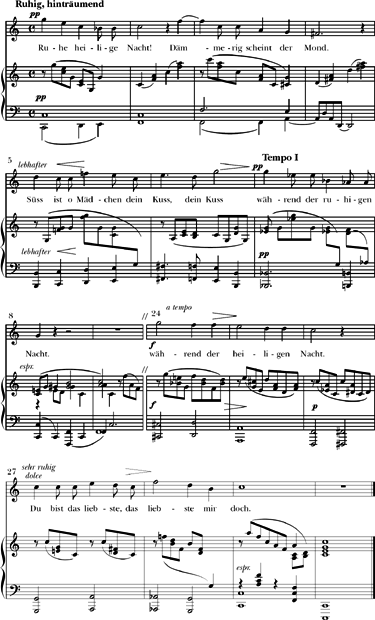

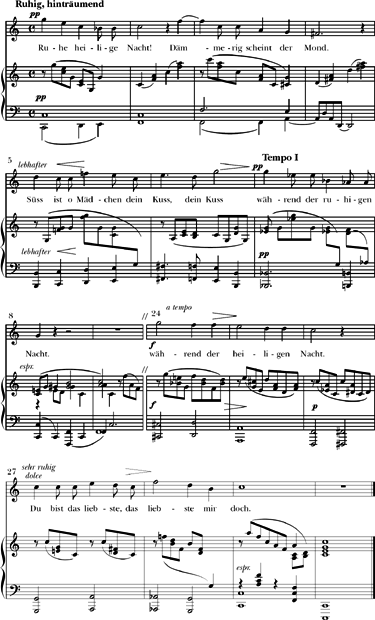

Zemlinsky and Schoenberg present an intriguing contrast in Brahms reception. Although the former was the more impeccably trained and technically proficient composer—and as such can perhaps be seen as representative of many similar figures of his generation—it was in fact Schoenberg who probed more deeply into the essence of Brahms’s music. Let us look first at Zemlinsky’s song Heilige Nacht, which was published at the head of his first collection of lieder, op. 2, in 1897 (Example 1). The anonymous poem, a hymn of praise to the night, which cloaks everything in a cloak of tranquility—“even sorrow is sweet”—is of a type that attracted Brahms strongly.9 The more specifically musical characteristics of Zemlinsky’s song that derive from his study of Brahms can be itemized:

the descending, broad triadic melody (mm. 1-4)10

the strong stepwise bass line (especially mm. 1-6)11

the arpeggiated figuration in the right hand of the accompaniment, which is in diminution of vocal rhythm and motives (mm. 1-8)12

the dip toward the subdominant at the very beginning (mm. 1-2)13

the sudden move, by third, from a G to an E-flat harmony in  position (mm. 6-7)14

position (mm. 6-7)14

the extension or augmentation of “während der heiligen Nacht” to create an irregular three-measure phrase (mm. 24-26)15

the final plagal cadence of the song (mm. 29-30)16

Despite their distinguished pedigree, these techniques fail to add up to a successful song. First, the phrase structure is too square: the rather rigid succession of two-measure units in the opening section, through measure 8, is scarcely concealed by the small modifications, such as in measure 6, where Zemlinsky repeats the words “dein Kuss” in order to extend the phrase another half measure. A subtler grasp of Brahmsian technique might have led to the kind of asymmetry and irregularity that Schoenberg delighted in pointing out in Brahms songs in his essay “Brahms the Progressive.”17 Brahms himself would never be guilty of undermining what is clearly supposed to be a magical moment, the shift to the E-flat  chord in measure 7, with an almost verbatim repetition of the opening theme. In Brahms such special harmonic expansions are almost always accompanied by—or coordinated with—a further-reaching melodic or thematic development.18

chord in measure 7, with an almost verbatim repetition of the opening theme. In Brahms such special harmonic expansions are almost always accompanied by—or coordinated with—a further-reaching melodic or thematic development.18

Example 1. Zemlinsky, Heilige Nacht, op. 2, no. 1 (1897).

Despite its surface resemblance to Brahms, the harmonic syntax of Heilige Nacht also betrays an un-Brahmsian awkwardness. The root-position IV chord in measure 2 is too emphatic; it virtually brings harmonic motion to a standstill. When Brahms employs a root-position subdominant near the beginning of a piece, it is more a harmonic inflection, imparting a delicate ambiguity.19 Zemlinsky’s actual cadence to F in mm. 8-9, though perhaps intended as a fulfillment of the opening gesture, is likewise unconvincing. The tonic has barely been reestablished in measure 7 when it is transformed into an augmented chord that is made to function as a dominant. The augmented sonority with an added major seventh sounds particularly bizarre in the prevailingly consonant context.

If I seem to have been too hard on what is in many respects an attractive song, it is because Zemlinsky seems to me to be very good at appropriating many of the stylistic traits of Brahms without really absorbing the fundamental compositional principles. This aspect of his art has been pointed out by Adorno, who in his excellent essay of 1959 suggested that Zemlinsky was a genuine eclectic, “someone who borrows all possible elements, especially stylistic ones, and combines them without any individual tone.”20 Adorno tries to strip the term “eclectic” of its pejorative connotation, arguing that Zemlinsky was in fact something of a genius in his “truly seismographic capacity to respond to all the temptations with which he let himself be inundated.” I would argue here that his “seismographic” receptivity prevented him from really absorbing the essence of Brahms. He registered the aftershocks, so to speak, but failed to locate the source of the tremor.

This tendency can be seen in Zemlinsky’s early chamber music as well, especially in the First Quartet in A Major, op. 4, composed in 1896 and published by Simrock in 1898. The first group of the first movement (Example 2) constitutes a virtual encyclopedia—grab-bag might be a more appropriate term—of Brahmsian metrical devices. Nowhere in the first group is the notated  meter presented unambiguously. At the outset the measure is divided as if in

meter presented unambiguously. At the outset the measure is divided as if in  (mm. 1-2). In the next measure the two lower parts move in

(mm. 1-2). In the next measure the two lower parts move in  , the second violin in

, the second violin in  , and the first violin somewhere in between. At the climax in mm. 9-12, Zemlinsky presents (although he does not notate) a dizzying alternation of

, and the first violin somewhere in between. At the climax in mm. 9-12, Zemlinsky presents (although he does not notate) a dizzying alternation of  and

and  according to the pattern:

according to the pattern:  . After the fermata, the metrical roller coaster resumes its course.

. After the fermata, the metrical roller coaster resumes its course.

In his commentary on this movement Rudolf Stephan has suggested that “rhythmic complications of this kind point to the model of Brahms, who, however, does not employ them in this (almost) systematic fashion.”21 Stephan’s parenthetical “almost” betrays an appropriate diffidence. In fact, it is Brahms who is the more systematic, as a comparative glance at his Third Quartet in B-flat, op. 67, will show. Brahms, like his follower Zemlinsky, continually reinterprets the notated  meter. But where Zemlinsky dives headlong into complexity and conflict, Brahms unfolds a gradual, subtle process (Example 3a). In mm. 1-2 he places accent marks on the normally weak third and sixth beats of the measure. In measure 3 these accents are intensified by forzandos. Only in measure 8 does Brahms introduce an actual hemiola. This hemiola serves an important structural function: it marks the first arrival on the dominant and the beginning of the B section of the ABA′ design of the first group. The following transition unfolds unproblematically in

meter. But where Zemlinsky dives headlong into complexity and conflict, Brahms unfolds a gradual, subtle process (Example 3a). In mm. 1-2 he places accent marks on the normally weak third and sixth beats of the measure. In measure 3 these accents are intensified by forzandos. Only in measure 8 does Brahms introduce an actual hemiola. This hemiola serves an important structural function: it marks the first arrival on the dominant and the beginning of the B section of the ABA′ design of the first group. The following transition unfolds unproblematically in  , but the conflict between duple and triple articulation of the measure finds new expression in the notated

, but the conflict between duple and triple articulation of the measure finds new expression in the notated  meter of the second group (Example 3b). As in the first group, the meter is carefully coordinated with the thematic and formal procedures: the arrival of

meter of the second group (Example 3b). As in the first group, the meter is carefully coordinated with the thematic and formal procedures: the arrival of  coincides with a new theme and the confirmation of the dominant key area.

coincides with a new theme and the confirmation of the dominant key area.

Example 2. Zemlinsky, String Quartet no. 1 in A Major, op. 4, movement 1, mm. 1-13.

Example 3. Brahms, String Quartet no. 3 in B-flat Major, movement 1, mm. 1-12, 63-65.

The implication of the above discussion may seem self-evident: no one could compose Brahms as well as Brahms himself. Yet my point is that a highly talented composer like Zemlinsky could master many of the most complicated Brahmsian skills without using them sensitively. He could sound Brahmsian without really composing Brahmsian.

But as he matured, Schoenberg seemed to look more deeply into matters of Brahmsian technique and expression. The song Mädchenlied, set to a text by Paul Heyse (a favorite poet of the master), shows a different level of absorption of Brahms. The song, probably written in 1896-97 (the manuscript is undated), bears many of the outward aspects of Brahms’s style (see the first strophe, Example 5): a modified strophic form, a broad triadic melody, and a primarily diatonic harmonic framework. Also reminiscent of Brahms (and to some extent of Dvorák) is the quasi-pentatonic opening melody, with its particular emphasis in measure 2 on the melodic sixth degree, B, and the harmony of B minor.23

But it is in the more subtle relationships between voice and piano and in the fluid phrase structure that Schoenberg’s song reveals a more genuine Brahmsian inheritance. In the first two phrases, mm. 1-5, the accompaniment repeats a brief three-note motive, marked x in Example 5. In mm. 6-7 this motive migrates from the piano into the voice, at the words süsse and kredenz dem. This motivic transference forms part of a still more sophisticated exchange of material between voice and piano. As the voice reaches a half-cadence on the dominant in measure 5, the piano begins a restatement of what was originally the vocal theme, now in the dominant. From the second half of measure 6, this restatement begins to deviate slightly from the original (an exact transposition of the vocal melody of measure 3 would bring an E in the right hand on beat 3 of measure 6), but the contour and rhythms are fully recognizable through measure 7.

Example 4. Schoenberg, Piano Piece (1894), mm. 1-7.

This piano statement of the melody actually overlaps with the conclusion of the first vocal phrase in measure 5 and the beginning of the next one in measure 6. There is thus an asynchronous relationship between voice and accompaniment, perhaps intended by Schoenberg as a musical corollary of the drunken beggars outside the tavern door. The voice and piano get back into phase in measure 8, for the final phrase of the strophe.

In Mädchenlied Schoenberg seems to have assimilated basic compositional principles much more completely than the Zemlinsky of Heilige Nacht. The same can also be said of his own D-Major String Quartet of 1897 in comparison with Zemlinsky’s quartet of the preceding year (with which Schoenberg was undoubtedly familiar). Especially impressive in the Schoenberg work is the motivic technique of developing variation, in which one thematic idea is drawn from the preceding in a fluid, almost continuous process.

Example 5. Schoenberg, Mädchenlied (ca. 1896-97), mm. 1-12.

Example 6a shows part of the ternary first group of Schoenberg’s first movement. Already in its second two measures the main theme begins to develop, as mm. 3-4 take shape as a free but recognizable retrograde of mm. 1-2. Measures 1-4 function as an antecedent, mm. 5-12 as an expanded consequent deriving quite clearly from what has preceded. The rhythm of four slurred eighth notes in measure 5 (marked y) develops from the second half of measure 3. The rhythmic profile of measure 6 derives from the figure (marked x) spread across the bar line between mm. 2-3, where the dotted quarter note has an accent. The consequent phrase develops the implications of that accent, as it were, by shifting it to the downbeats of mm. 6 and 8. In the brief B segment of the first group, beginning in measure 13, the eighth-note idea is further modified (y′). In pitch content the motive retains the neighbor-note motion of the consequent form (mm. 5, 7, and 9).

Example 6. Schoenberg, String Quartet in D Major (1897), movement 1: (a) mm. 1-17; (b) mm. 33-39.

This developmental process continues well past the first group, as is shown in Example 6b, which presents the climax of the transition and the beginning of the second group. Here y is presented fortissimo, then gradually “liquidated,” as Schoenberg would later describe the process of reducing a theme or motive to its basic elements.24 The motive is then immediately regenerated in the inner parts of the second theme, which begins in measure 39.

Schoenberg’s strategy in this movement is clear: he seeks to saturate the texture with motive y in its various forms. Instead of using “filler” or empty figuration, he attempts to make all parts, and all moments, thematically significant. These are precisely the kind of techniques that he and his pupils would later admire and analyze in the music of Brahms. The D-Major Quartet and the song Mädchenlied both demonstrate how early and how well Schoenberg grasped these basic Brahmsian precepts.

In his later writings, Schoenberg would disparage the practice of composing “in the style” of a recognized master. He maintained that what most people call “style” is only an external “symptom”: “To believe, when someone imitates symptoms, the style, that this is an artistic achievement—that is a mistake with dire consequences.”25 In his early works Schoenberg was himself somewhat guilty of adopting the symptoms of Brahms. But what is admirable, and what sets him apart even from technically more accomplished composers like Zemlinsky, is his concern with finding and appropriating underlying compositional principles, such as that of continuous motivic development. It is these principles to which he was to cling even as his “style” changed radically in the years after 1899.

More overt homage to Brahms is paid by two piano pieces composed around the same time. One, titled Rhapsodie and subtitled “Den Manen Johannes Brahms,” is a large, turbulent work modeled closely on Brahms’s Rhapsodies, op. 79. It was published in 1899 as op. 24, no. 6. The other piano piece, the very opposite in mood, is titled Resignation and subtitled “3. April 1897—J. Brahms †,” the date of Brahms’s death (on or shortly after which it may have been composed). It was published in 1899 as op. 26, no. 5.

Resignation is a tombeau for a master whom Reger admired, and from whom virtually his entire oeuvre springs (the other main source is Bach). Although it can hardly be taken as typical of Reger’s music, the intentionally exaggerated “Brahmsian” spirit of the piece nevertheless makes it a wonderful specimen of Brahms assimilation by the younger generation of composers. In Resignation we can distinguish three levels of response to Brahms, which might be called quotation, allusion, and absorption. These can be considered not as exclusive categories, but as points on a spectrum of Brahms influence ranging from the very obvious to the almost undetectable or undocumentable.

Max Reger, 1902.

The piece ends with an unmistakable quotation of the theme from the Andante of Brahms’s Fourth Symphony (Example 7a), which appears in its original key, E major, even though Resignation has been in A major up to that point. (It thus ends in the dominant!) Although the quotation in itself hardly represents a sophisticated degree of Brahmsian assimilation, Reger leads up to it by a wonderfully subtle process of allusion and absorption.

Example 7b presents the opening portion of the piece. (The piece as a whole has an ABA’ form, like many of Brahms’s late piano works.) Needless to say, we find here many of the “symptoms” of Brahms’s piano style, such as those described by Niemann in 1912: “passages in thirds and sixths, orchestral doublings, wide spacings, use of the deep bass register…[and] a tendency toward syncopated and triplet figures of all kinds.”28 But there is more as well, including allusions to at least three of Brahms’s late Intermezzi: op. 116, nos. 4 and 6, both in E major; and op. 118, no. 2, in A major (Example 8). Reger’s bass octaves recall Example 8a; the distinctly polyphonic texture, with active middle voices, is a feature of both 8a and 8c. Reger also reinterprets the opening gesture characteristic of all three Intermezzi: Resignation begins on an upbeat with a root-position tonic chord, which moves on the subsequent downbeat to a ii6 (the chord is complete only when the middle-voice suspension resolves on beat 2). Brahms also has a tonic chord on the upbeat and then moves to some kind of “pre-dominant” chord: in Example 8a, vi6; in 8b, a passing chord over A, then ii; in 8c, a IV . As in Reger, the precise formation of these downbeat chords is made initially unclear by appoggiaturas and suspensions.

. As in Reger, the precise formation of these downbeat chords is made initially unclear by appoggiaturas and suspensions.

Example 7a. Reger, Resignation, op. 26, no. 5 (1899), mm. 51-56.

Example 7b. Reger, Resignation, op. 26, no. 5 (1899), mm. 1-10.

In Example 8b these procedures generate considerable metrical ambiguity. Our ear tends to hear the strong root-position chord as a downbeat, and the phrasing suggests a broad  meter rather than the notated

meter rather than the notated  . At the approach to the dominant in Resignation, mm. 6-9, Reger draws upon precisely these kinds of metrical ambiguity or conflict (as suggested in Example 7). As we listen (at least for the first time), mm. 5-6 suggest a

. At the approach to the dominant in Resignation, mm. 6-9, Reger draws upon precisely these kinds of metrical ambiguity or conflict (as suggested in Example 7). As we listen (at least for the first time), mm. 5-6 suggest a  hemiola superimposed over the notated

hemiola superimposed over the notated  . But the downbeat of measure 7 does not, as we might expect, restore the notated meter unequivocally.

. But the downbeat of measure 7 does not, as we might expect, restore the notated meter unequivocally.

Example 8. Brahms Intermezzi: (a) op. 116, no. 4; (b) op. 116, no. 6; (c) op. 118, no. 2.

Instead, the implied  measure is stretched, as it were, to accommodate the cadential approach to E through the circle of fifths, C

measure is stretched, as it were, to accommodate the cadential approach to E through the circle of fifths, C —F

—F —B—E. Reger now accelerates the harmonic rhythm, so that while the C

—B—E. Reger now accelerates the harmonic rhythm, so that while the C lasts a half note, or a full beat in

lasts a half note, or a full beat in  , the F

, the F and B are only a quarter note each. The cadential goal, E, thus arrives on the notated last beat of measure 7. The two subsequent measures confirm E with the Phrygian approach through C-major and F-major triads. This cadence subtly foreshadows the actual quotation from Brahms’s Fourth (Example 7a), with its prominent

and B are only a quarter note each. The cadential goal, E, thus arrives on the notated last beat of measure 7. The two subsequent measures confirm E with the Phrygian approach through C-major and F-major triads. This cadence subtly foreshadows the actual quotation from Brahms’s Fourth (Example 7a), with its prominent  s.

s.

The Phrygian passage in the Reger prolongs the metrical ambiguity just long enough to bring the phrase to close on the notated second beat of measure 9, thus allowing for a varied restatement of the opening theme to begin in its proper place, on beat 3. The tonic now reappears modified by another Brahmsian gesture: the A enters half a beat too early, on the second half of the beat of measure 9, sounding deep in the bass underneath the prevailing dominant harmony.29

The kind of procedures involving meter, harmony, and phrase structure that are manifested by mm. 6-9 of Resignation fall under the category of absorption discussed above. Reger is making no quotation of, or allusion to, any specific passage in Brahms. Rather, he seems fully to have internalized or absorbed a number of Brahms’s most characteristic compositional techniques. This is the kind of influence that Charles Rosen has identified as the most profound, where the study of sources or models for a particular work “becomes indistinguishable from pure musical analysis.”30

As a self-assured personality, Brahms raised his head proudly among the many Mendelssohn-Schumann epigones and struck out on his own path, which wound around the noble palace in which Beethoven reigned. That this path did not lead into unknown areas, that Brahms opened no new perspectives—this should be conceded to his opponents without hesitation. But is it really such a misfortune that on the broad path along which art develops there should be resting places as well as signposts?31

Such a patronizing assessment can irritate us today as much as it did the young Reger at the time. Although some critics of the fin de siècle like Lessmann saw Brahms as a dead end or “resting place,” younger composers felt differently. The most talented of these, including Schoenberg, Reger, and even Zemlinsky at his best, found plenty of “signposts” in Brahms’s music. One merely needed the inclination and skill to interpret them. As these composers matured, they adapted and eventually sublimated Brahmsian principles and techniques to forge some of the most impressive musical achievements of the early modernist period.

NOTES

Portions of this article appeared in Part I of my book The Early Works of Arnold Schoenberg, 1893-1907 (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1993).

position (mm. 6-7)14

position (mm. 6-7)14

meter presented unambiguously. At the outset the measure is divided as if in

meter presented unambiguously. At the outset the measure is divided as if in  (mm. 1-2). In the next measure the two lower parts move in

(mm. 1-2). In the next measure the two lower parts move in  and

and  . After the fermata, the metrical roller coaster resumes its course.

. After the fermata, the metrical roller coaster resumes its course. meter of the second group (Example 3b). As in the first group, the meter is carefully coordinated with the thematic and formal procedures: the arrival of

meter of the second group (Example 3b). As in the first group, the meter is carefully coordinated with the thematic and formal procedures: the arrival of

—E

—E

meter rather than the notated

meter rather than the notated

—F

—F