At the beginning of the twenty-first century, we can hear Brahms’s music wherever and whenever we like. But can we locate its source? The composer himself is long dead, even if his defiant gaze and formidable beard still haunt us. His printed musical texts survive, of course, taking up generous shelf space in libraries, music shops, and homes throughout the world, but their circles and lines will always remain mutely imprisoned on the page. Some have preferred this state of affairs, believing that musical notes are better seen than heard. The theorist Heinrich Schenker, for instance, believed that “a composition does not require a performance in order to exist,” and that the “realization of the work of art can thus be considered superfluous.”1 Schenker was following the lead of Eduard Hanslick, Brahms’s friend and critical ally, by locating musical works in a transcendent realm. For Hanslick, music ultimately consisted of “sounding forms set in motion” that floated free of the intentions and desires of the people who produced them, while Schenker went even further by claiming that music’s true significance lay entirely beyond the auditory domain.2 If, however, we want to register Brahms’s music empirically, then we must allow for the intercession of human bodies and minds between the composer’s conceptions and our perceptions. Collectively, these people constitute the legion of performers who have brought Brahms’s notation to audible life for more than 150 years. They have transformed his circles and lines into an array of sonorous phenomena that unfold in music’s eternal present while simultaneously acknowledging their origin in various strata of the past.

The role played by performers in the (re)production of European art music has been generally conceived in transmissive and mediatory terms under which performers form a bridge between the composer and listener. The success of a performance is thus often judged according to how faithfully it is thought to convey the composer’s intentions, however indecipherable they might be. In this essay, I want to suggest other ways of constructing the relationship between composer, performer, and listener (or the aggregation of performers into an ensemble and listeners into an audience). To start with, what happens when two—or even all three—of these roles coalesce within one individual? A concrete example of this state of affairs survives in the form of Brahms’s maddeningly indistinct piano recording of his own Hungarian Dance no. 1, WoO 1, made in 1889.3 Conversely, there are intriguing instances where the implications of Brahms’s music seem to exceed the agency of those who perform it, throwing up multiple personae. Some of them may be “embodied” by the musical gestures of instruments or voices, but others seem to invoke the presence (or absence) of the composer, address a specific listener, or even represent a broader historical or cultural force.4 At such moments, Brahms’s music can be heard to send a message through the medium of performance itself. Any attempt to locate the source of this communicative power has to contend with the multiple agencies of performers and listeners, even if we are always mindful of Brahms’s shadowy figure behind the scenes.

To explore these issues and how they were manifested within Brahms’s musical world, I will focus here on two instrumental works whose early performances featured Brahms as both composer and pianist: the Second Piano Concerto, op. 83 (1881), with which Brahms reinvented himself as a new type of keyboard virtuoso in a manner that belatedly responded to hostile criticism of the First Piano Concerto more than twenty years previously; and the Sonata for Piano and Cello in F Major, op. 99 (1886), which Brahms was prompted to write by (and which he subsequently premiered with) the cellist Robert Hausmann. I will rely on biographical information and historical evidence pertaining to the cultural status of musical performance in my discussion of the concerto, whereas my closer reading of the sonata will draw on recent theoretical attempts to understand musical performance in semiotic and gestural terms. My aim is thus to provide different contexts for the projection and interpretation of Brahms’s music by illustrating how the composer’s approach to performing his own works changed according to personal, public, and generic expectations, and how the traces left by these various forms of embodiment have continued to condition the responses of performers, listeners, and critics right up to the present.5 Along the way, I hope to reveal and clarify some of the historical and aesthetic complexities that underpin conceptions of what it might mean to “play Brahms.”

Debatable early experiences in Hamburg’s taverns notwithstanding, Brahms made his public debut as a concert pianist at the relatively late age of fourteen.6 The recital was only a modest success. His teacher Eduard Marxsen (to whom Brahms would later dedicate the Second Piano Concerto) recalled that his pupil’s progress “was indeed remarkable, but not such as to give evidence of exceptional talent, only the results of great industry and unremitting zeal.”7 Despite (or perhaps because of) his natural shortcomings, Brahms sustained ambitions of becoming a true virtuoso throughout the 1850s, and the work around which they coalesced was the First Piano Concerto, op. 15. The genesis of the concerto was notoriously tangled: Brahms had started composing a sonata for two pianos before orchestrating it as a symphony. Ultimately, the genre of the concerto seemed to offer a compromise between these rival conceptions while also presenting Brahms with the chance to star as the protagonist of his own musical drama.8 A letter to Clara Schumann shows that this prospect had fired his imagination: “Do you know what I dreamt last night? I had turned my accursed symphony into a piano concerto and was playing it: a first movement, a scherzo, and a finale, terribly difficult and grand. I was absolutely transported.”9 But in 1859 Brahms’s dream would turn into a nightmare when he finally performed the concerto in Leipzig. The critic Eduard Bernsdorf poured scorn not only on his writing for the piano (“Herr Brahms has deliberately made the pianoforte part of his concerto as uninteresting as possible”) but also on his ability to play it (“Herr Brahms’s technique as a pianist does not attain the standard that we have a right to expect of today’s concert pianists”).10

Such sour criticism stood in painful contrast to the adulation that had been lavished on Franz Liszt, the piano virtuoso extraordinaire who abandoned the concert platform in 1847 in order to dedicate himself to composition. Brahms abhorred Liszt’s music but unreservedly admired his pianism: “If you never heard Liszt, you really have nothing to say…. His piano-playing was something unique, incomparable, and inimitable.”11 Even Hanslick was spellbound by Liszt’s cascades of notes and physical presence: “Not only does one listen with breathless attention to his playing; one also observes it in the fine lines of his face…. All this has the utmost fascination for his listeners, especially his female listeners.”12

Conversely, while Brahms’s works elicited Hanslick’s approval, the critic’s response to how the composer performed them was decidedly cooler. When Brahms played the newly written Handel Variations, op. 24, at his Viennese concert debut in 1862, Hanslick made his reservations clear.

[Brahms] strives exclusively to serve the spirit of the composition, and he avoids almost shyly all appearances of self-important pageantry. Brahms has at his disposal a highly developed technique, which lacks only the final gleaming polish, the final energetic self-confidence that would permit us to call him a virtuoso. Brahms handles the most brilliant aspects of performance with a sort of casualness…. It might seem like a compliment to say that he plays more like a composer than a virtuoso, but such praise is not entirely unqualified. Inspired by the desire to let compositions speak for themselves, Brahms neglects—especially in performance of his own works—much of what the player is obliged to do for the composer. His playing resembles that of the astringent Cordelia, who would rather conceal her innermost feelings than expose them to the public…. Brahms handled his own works somewhat shabbily. His F-Minor Sonata, a composition so wondrously “sung to itself,” was played by Brahms more “to himself” than in a clearly and crisply presented manner.13

By depicting Brahms as a servant and likening him to Shakespeare’s demure Cordelia, Hanslick implied that he lacked the bravura and visual flair that characterized the Lisztian virtuoso. But Hanslick’s critique also hinted at how this deficiency might be turned to Brahms’s advantage: if Liszt’s virtuosity was Faustian, Brahms’s high-minded renunciation of showmanship placed him on the side of the angels. His Cordelian unwillingness to flatter and his devout dedication to the works he played could be construed as an index of a moral superiority capable of restoring virtue to debased virtuosity. Describing Brahms at the keyboard, his friend Joseph Viktor Widmann pursued these implications in nationalistic terms, emphasizing the Innigkeit—a term connoting both depth and intimacy—that Brahms’s unlovely appearance concealed, and thus exemplified.

It is true, the short square figure, the almost straw blond hair, the jutting lower lip that lent the beardless youth a slightly sarcastic expression, were conspicuous and hardly prepossessing peculiarities; but his entire aspect was permeated by strength. The broad lionlike chest, the Herculean shoulders, the mighty head at times tossed back energetically when playing, the contemplative, beautiful brow glowing as if by an inner light, and the Germanic eyes framed in blond lashes and radiating a marvelously fiery glance.14

In the absence of Liszt’s jaw-dropping legerdemain, the obstinacy of Brahms’s “jutting lower lip” symbolized his determination to tackle the technical obstacles strewn in his path at the keyboard. The Paganini Variations, op. 35 (1862-65), exemplify this type of muscular, abrasive virtuosity, and in the light of his complex rivalry with Liszt, the circumstances surrounding their conception, composition, and early performance history are especially telling. After befriending the pianist Carl Tausig toward the end of 1862, Brahms presented him with “something to break [his] fingers over” in the form of an early version of the Variations.15 By acquiring Tausig as a virtuosic proxy and offering him music based on Paganini’s famous A-Minor Caprice, Brahms was flagrantly encroaching on Liszt’s territory. Tausig had been Liszt’s favorite protégé and was later to compose a number of symphonic poems; what is more, Liszt had dealt with the same theme in his Études d’exécution transcendante d’après Paganini, published in 1840, revised in 1851, and dedicated to none other than Clara Schumann.16 Brahms’s competitive intent was thus unmistakable. Considered both as musical literature and as substrate for performance, the Paganini Variations suggest that Brahms and Tausig combined to promote an anti-Lisztian doctrine of virtuosity that elevated effort above inspiration but preferred to mask that effort rather than to flaunt it. While Liszt conjured with special effects, Brahms and Tausig’s only illusion was that there was no illusion: virtuosity was subjected to Brahms’s rigorous compositional work ethic.

By 1868, the completion of the German Requiem marked the symbolic laying to rest of Brahms’s virtuoso aspirations, along with the end of the financial insecurity that had sustained them. Thereafter the standard of his playing would steadily deteriorate, and he increasingly privileged the score over its realization. Thus when Florence May sought Brahms’s advice on playing Mozart, he pointed to the score, saying, “It is all there”; on another occasion, he remarked, “When I play something by Beethoven, I have absolutely no individuality in relation to it; rather I try to reproduce the piece as well as Beethoven wrote it. Then I have quite enough to do.”17

The austerity of this approach had ramifications for the fabric of Brahms’s mature music; in Carl Dahlhaus’s words, the perception of its qualities relied on

a form of musical cognition based on the thematic process, a process in which every alteration infringed against the substance of the original…. A melody may be embellished without damage; a thematic process, however, must be interpreted, its latent structures made audible, before it can be comprehended.18

For Dahlhaus, the imposition of the virtuoso’s personality through improvisation or ornamentation would imperil the audible logic of Brahms’s thematic development, and thus the organicism of the work as a whole. Yet Dahlhaus’s interpretation of the relationship between performer and composer is perhaps too binaristic. Brahms did not eliminate virtuosity from the discourse of his thematic arguments; rather, he reconfigured it, treating it as a minimum requirement for the performer while simultaneously transferring its attributes to the compositional realm. For those playing Brahms’s music, fidelity to the text and virtuosity became one and the same, in that the latter was required merely to realize the former. A prime example is provided by Brahms’s 1872 condensation of his Hungarian Dances from piano duet to piano solo. As Charles Rosen has pointed out, music that is fairly simple when distributed among four hands becomes a strenuous ordeal for two, and yet with ears alone one is hard-pressed to distinguish between the renditions of a pair of amateurs and a single sweating virtuoso.19 In Brahms’s more “serious” music, spontaneous embellishment by the performer was replaced by a hefty dose of written-out virtuosity from the composer in the form of a motivic density that had to be unpicked faithfully and unfussily. The pianist’s task became subordinate and thankless in equal measure.

The ultimate measure of this task was Brahms’s collection of 51 Übungen (exercises) for piano, WoO 6, written over several decades and gathered together for publication in 1893 as his last contribution to the piano literature.20 The Übungen adhere to the utilitarian tradition of Muzio Clementi and Carl Czerny in their dissection of virtuosity.21 Brahms suggested to his publisher Fritz Simrock that the cover should feature some unusual illustrations: “All possible instruments of torture should be represented, from thumbscrews to the Iron Maiden; perhaps some anatomical designs as well, and all in lovely blood-red and fiery gold.”22 If the Übungen were a grisly warning to the would-be virtuoso, they also demystified and codified virtuosity, breaking it down to its components in order to carve out a steep but scalable gradus to the summit of Parnassus, Brahms’s “real” music. Brahms’s writing down of his Übungen fixed the unscripted process of practice as a text; the exercising of Brahms’s fingers was recorded in notation, and performance and score were thus brought together.23

The publication of the Übungen as a single set of exercises disguised the fact that they had emerged in parallel with the writing of Brahms’s most challenging piano works. Although most of the Übungen were written in the 1850s and ’60s, about twenty of the fifty-one exercises date from the early 1880s, and they were almost certainly practice aids for Brahms’s performances of the Second Piano Concerto. The relationship between the exercises, written around the same time as the concerto, is evident in the type of figuration they share. The relationship is also audible in the concerto’s musical figuration and syntax; in particular, Brahms’s unusually heavy reliance on the sequential repetition of material in the concerto might be heard to draw on the lexicon of the exercise.

It is understandable that Brahms needed to write new exercises to lick his rusty technique into shape. The Second Piano Concerto is an ordeal for any soloist, and Brahms would perform it no fewer than twenty-one times over the winter of 1881-82.24 Witnesses to his playing told of how he relished the difficulties of his own music. George Henschel remembered Brahms performing the notorious octave trills in the First Piano Concerto (“He would lift his hands up high and let them come down on the keys with a force like that of a lion’s paw. It was grand!”) and in 1892 Brahms wrote to Clara Schumann of “the peculiar appeal which is always connected to a difficulty.”25 But descriptions of Brahms’s performances of the Second Piano Concerto raise serious doubts about whether he prevailed over its technical challenges. Brahms’s playing was tolerated rather than celebrated; an anonymous contributor to the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung echoed Hanslick’s review of Brahms’s Viennese debut in reminding readers that “we must remember that [Brahms] is primarily a composer…. Details lack finish, and his playing often seems somewhat colorless, but on the whole he grips the audience through his objective and stylish rendering.”26

Privately, other members of Brahms’s audiences were more forthright. The Irish composer Charles Stanford heard the composer perform his new concerto in Hamburg, and published a vivid account of it after Brahms’s death:

His piano playing was not so much that of a finished pianist, as of a composer who despised virtuosity. The skips, which are many and perilous in the solo part, were accomplished regardless of accuracy, and it is no exaggeration to say that there were handfuls of wrong notes. The touch was somewhat hard and lacking in force-control.27

Berta Geissmar, secretary to Wilhelm Furtwängler and Thomas Beecham, relayed what were presumably her mother’s impressions of the composer’s playing: “Brahms himself was not a good interpreter of his works. He played his concerto in B-flat major in the historic Rokokosaal of the Mannheim theatre and his clumsy fingers often hit the wrong notes.”28 Those closer to Brahms expressed similar reservations. Florence May had attended the rehearsal before the performance described by Stanford and “did not think Brahms’s playing what it had been. His touch in forte passages had become hard, and he did not execute difficulties that before he had mastered with ease.”29 Clara Schumann confided to her notebook in 1882 that “Brahms plays more and more abominably—it’s now nothing but thump, bang, and scrabble.”30

Was the composer in denial of his shortcomings at the keyboard? Apparently not: May recalled that as early as 1871 “he was fully aware of his failings”—striking wrong notes and a hardness of tone—“and warned me not to imitate them.”31 Tausig was long dead, but had Brahms wanted a technically adept performance from a willing deputy, Hans von Bülow was on hand—indeed, Bülow conducted the rehearsal that May witnessed, and she openly wished that the two had swapped roles.32 By 1885, even Liszt acknowledged that Bülow had performed the concerto “beautifully,” whereas Brahms had played it “rather messily.”33

One means by which Brahms compensated for his failing dexterity was his voice. His playing had been accompanied by a “gentle humming” since the 1850s, but in later years this noise transformed into what Ethel Smyth described as “a sort of muffled roar, as of Titans stirred to sympathy in the bowels of the earth.”34 Ferdinand Schumann was less poetic in registering “a sort of gasping, grumbling or snoring,” which was “audible as far back as the tenth row,” and Brahms’s biographer Max Kalbeck once heard such extraordinary sounds accompanying Brahms’s solitary piano-playing (“a growling, whining, and moaning, which at the height of the musical climax changed into a loud howling”) that he thought the composer must have surreptitiously acquired a dog.35 To adapt Roland Barthes, these sounds could be interpreted as the “grain” of Brahms’s playing; they underpinned the fistfuls of notes both right and wrong, masking his inaccuracies and watermarking his soundscape with inimitable qualia.36

Brahms’s grunting may have been designed to emphasize his masculinity: as a young man he was embarrassed by his high-pitched voice, and he tried to lower it, to somewhat unpleasant effect. Consciously or otherwise, he seems to have relished the greater resonance that his maturity (and probably his increased girth) afforded his voice, and thus his sense of male identity. It seems likely that his performance of the concerto took advantage of these properties, for when he met the pianist Ella Pancera, who played the Second Concerto in Vienna, he told her that his piece was “decidedly not for little girls.”37 But the gendered terms in which Brahms conceived the performance of his concerto take on a different form in relation to the practice of composition, as illustrated by a letter he wrote to Emma Engelmann: “What in the world doesn’t the man intend and reflect upon when creating, or the woman while playing the piano?”38 Although they may simply reflect widespread cultural prejudices, such remarks also hint at Brahms’s identification of the private, inner world of composing with the masculine, and the public, visual elements of performance with the feminine.

In this context, it is telling that the features that most strongly marked Brahms’s own style of performing were those that deflected interest from the ostentation of the virtuoso’s body and its gestures. His listeners were on the one hand drawn within, treated to the rumblings of Brahms’s inner workings, and on the other, steered away, forcibly reminded of his physical shortcomings. Ultimately, their attention was guided toward the music’s metaphysical location. Richard Specht remarked on this paradoxical way in which Brahms’s neglect of his audience somehow enabled its members to grasp the essence of the musical work: “The whole person was in this playing—and also the whole work: one seemed to possess it from that moment on, inalienably so…. He always played as if alone: he forgot the audience entirely, wholly immersed in his own world.”39

If, as Stanford alleged, Brahms “took it for granted that the public knew he had written the right notes, and did not worry himself over such little trifles as hitting the wrong ones,” then Brahms’s disregard for the niceties of piano technique anticipated Schenker by the privileging of musical metaphysics over aural phenomena.40 In pursuit of this aim, his execution of the concerto seems to have been calculated to create a discrepancy between score and performance. The misadventures of his fingers on the keyboard served to underscore the sureness of their grip on his pencil. The anonymous critic for the Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung described Brahms’s playing as if the pencil were still in his hand (“he draws … in outlines, but in great outlines”), which chimes with Marie Schumann’s description of his rendering of the concerto as “a spirited sketch.”41 By “despising virtuosity,” as Stanford put it, Brahms was augmenting his compositional authority: he was putting virtuosity to work.

Regardless of whether they heard Brahms’s pianism as a revelation or a hindrance, most audiences and critics responded enthusiastically to the concerto, leading Clara Schumann to write in her journal: “Brahms is celebrating such triumphs everywhere as seldom fall to the lot of a composer.”42 Positive responses to the Second Piano Concerto even spread to Brahms’s performances of the First, as an anonymous review of an 1884 performance in Berlin demonstrates: “Maestro Brahms played his D-Minor Concerto wonderfully, especially with regard to the understanding of the work, since he obviously does not display the qualities of a professional pianist.”43 The reverential tone of this review stands in stark contrast to Bernsdorf’s excoriation of Brahms’s Leipzig performance twenty-five years earlier, even though sloppy piano technique was acknowledged in both cases. Brahms had transformed the criticism that Bernsdorf had hurled at him into praise of a higher order: any discrepancies between work and performance were firmly resolved in favor of the former. The Second Piano Concerto, and the circumstances under which Brahms presented it, thus had a powerful and lasting impact on the way its predecessor was performed and heard.

Brahms’s biographer Walter Niemann grumbled about the unreasonable demands that Brahms made of the soloist throughout the Second Concerto:

The pianist who plays this…concerto must to a great extent renounce his position as a virtuoso and become a mere journeyman at the piano, executing the pianistic toil imposed upon him by the composer with groans—and by the sweat of his brow…. One sees and hears the pianist striving and battling with things that are as extraordinarily difficult and unmanageable as they are exacting and fatiguing.44

For a contemporary pianist who did not happen to be Brahms, the concerto offered little more than an opportunity for martyrdom. But for those who came after him, Brahms’s once-fearsome technical challenges eventually lost their power to intimidate, and recordings of both piano concertos now litter the catalogue. This process began even during his lifetime—after Brahms’s final performance of the Second Concerto in 1886, he was happy to retreat to the conductor’s podium while the Scottish-born Eugen d’Albert took over at the keyboard. Brahms was a great admirer of d’Albert, telling his friend Richard Heuberger that he no longer needed to play because he now had his own “court pianist.”45

Brahms’s two piano concertos thus expose the contingencies of writing and performing music in different ways. If the First evokes the Sturm und Drang of the young Brahms’s musical and emotional trauma, it was also the site of a belated middle-aged triumph: the mature composer made up for the shortcomings of the youthful pianist. The Second also bears the fingerprints of Brahms in both capacities, but stacks the deck in favor of the composer. It quickly became a redoubtable warhorse that compelled subsequent pianists to attain a level of dexterity that had eluded Brahms himself, but their virtuosic obedience to his score demonstrates the ultimate subservience of the performer to the work.

Within the genre of the romantic piano concerto, issues of agency and drama tend to be delineated with sweeping gestures that reflect an elemental contrast between individual and community. The nature of this relationship can be depicted and construed in many ways, but most of them identify the soloist as a protagonist whose personality is defined, developed, and ultimately vindicated against the massed forces of the orchestra.46 As mentioned above, this model has often been applied to Brahms’s First Piano Concerto: the turbulence of the opening tutti sets the stage for a mighty struggle from which the piano eventually emerges triumphant. The temptation to cast the figure of Brahms in the piano’s role is strong, especially in the light of his traumatic experiences with the Schumanns around the time of its writing, and his own performances of the concerto encouraged both friends and critics to identify his presence in the work under this rubric. But how might “Brahms” have manifested himself when performing works in other musical genres? Throughout his later Viennese years, Brahms was active as a conductor, accompanist, and chamber musician, and in each of these capacities his musical persona was projected and apprehended differently. The following attempt to reconstruct the premiere of his Sonata for Piano and Cello in F Major, op. 99, seeks to examine how Brahms’s role changed when he was co-star rather than leading light.

Robert Hausmann (see Figure 1), Brahms’s partner at the premiere, was a member of Joseph Joachim’s famous quartet and taught alongside the violinist at the Berlin Hochschule. In the early 1880s Hausmann became close to Brahms. He pestered the composer for a second cello sonata after having successfully revived the first, op. 38 in E minor, in 1885.47 Contemporary accounts of the two men’s qualities as performers can help conjure up an idea of how they might have sounded when playing the new F-Major Sonata together, and an attempt to define the terms on which they interacted can similarly enrich our understanding of the sonata’s syntax, structure, and gestural profile.

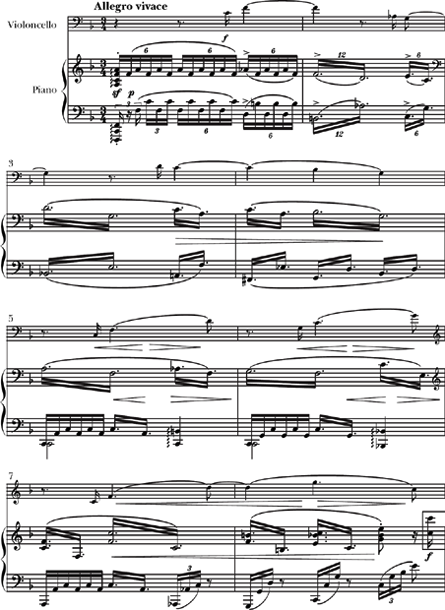

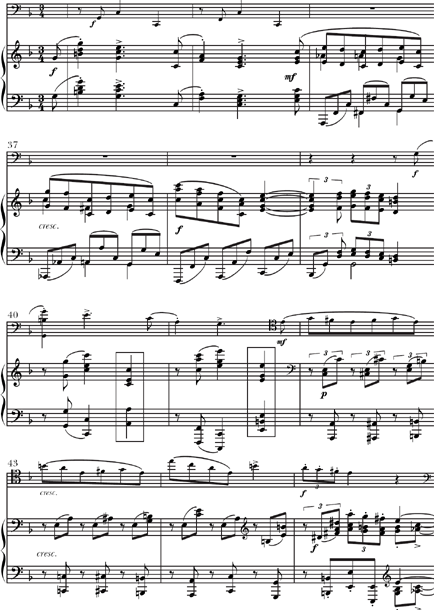

Fanny Davies, an English pianist who heard Brahms play his Piano Trio in C Minor, op. 101, described how he began the work by “lifting both of his energetic little arms high up and descending ‘plump’ onto the first C minor chord … as much as to say: ‘I mean THAT.’”48 Her observation suggests an unambiguous attribution of agency: Brahms simply means what he writes and consequently does. Such rhetoric is easily applied to the piano’s gruff roar at the outset of the first movement of op. 99 (see Example 1). But after this initial coup, the cello immediately assumes the limelight with its proud opening theme, while the piano recedes into a supporting role, providing little more than a metric and harmonic backdrop for the cello’s flamboyant gestures. In these opening measures, the cello’s bold monophonic line is concerto-like in invoking a solitary individual, perhaps even a heroic protagonist; in turn, the athematic tremolos in the first eight measures of the piano part might be understood to represent what Robert S. Hatten has called, in his taxonomy of types of musical agency, a “depersonalized external force.”49 As Margaret Notley has shown, this relationship can also be understood within a philosophical and aesthetic context (stretching from Hegel to Adorno) that links themes to the formal processes they undergo in terms that can be mapped onto the role of the individual within society.50 But on close inspection, questions of agency and representation quickly become ambiguous. The cello’s opening gestures may be bold, but they lack metrical grounding and repeatedly fall on weak beats, implying that its heroism is less confident than it appears. Rather than engaging in dialogue with the piano, the cello solipsistically muses on its theme in the manner of developing variation (mm. 9-20), a process that loses steam as the piano’s energetic sextuplets slacken into sixteenth notes.51 For its part, the piano immediately undermines the cello’s confident opening leap by shifting to a diminished-seventh harmony (a maneuver that brings to mind the opening of the Third Symphony, op. 90).52 Similarly, the piano’s single thematic contribution is offered as a counterpoint to the cello’s theme, first in the right hand and then in the left. Boxed in Example 1, it sounds a minatory tone that hints at a threat to the cello’s breezy optimism.

Figure 1. Robert Hausmann and Johannes Brahms, photograph taken by Maria Fellinger (right) in 1896.

Example 1. Brahms, Sonata for Piano and Cello in F Major, op. 99, movement 1, mm. 1-12.

The self-assured second subject, shown in Example 2, brings respite while performing a neat dialectical inversion of the opening. The piano becomes the protagonist while the cello provides resolute accompanymental support in C major.53 However, the two instruments do not pull together for long. When they swap roles once more, the piano’s C-major chords give way first to A minor and then to E minor, as boxed in Example 2, which combine to push the cello toward the latter key while unsettling it to the extent that the ending of the phrase is breathlessly truncated in measure 45.

The turbulent section that follows leads to an impassioned “third subject” from the cello, illustrated in Example 3, that hovers around A minor, despite a disorienting whole-tone scale in mm. 54-55; once again, roles are exchanged, and it is the piano’s firmly diatonic answer that clinches the cadence in this key, simultaneously revealing that both boxed chords in Example 2 have tonal ramifications beyond their immediate context.

Example 2. Brahms, op. 99, movement 1, mm. 33-45.

This “third subject” sounds new, but some of its features can be traced back to the first theme: The cello’s C-F fanfare has been inverted and augmented into a tritone, and the piano’s agitated sixteenth notes, which outline a diminished seventh, are reminiscent of the opening tremolos. Most tellingly, the piano’s cadential melody (boxed in Example 3) has been heard before as the counterpoint to the cello’s initial theme (boxed in Example 1).

Rather than the piano and cello combining to reinforce the normative dialectic of sonata form, then, their interaction results in a tripartite structure; instead of effecting a synthesis, the third element in this structure seems to point out the unexpected implications of the first two, undermining the confident C major of the second subject while revealing a dark side of the seemingly heroic first subject.54 Moreover, the uncomfortable logic of this third element seems to lie beyond the reach of either piano or cello insofar as they act alone as principal or external agents, thus indicating the presence of what Hatten calls a “narrative agent.” This type of agent takes the form of a “creative persona” who is “involved in ordering, arranging, and/or commenting upon the (sequence of) events of the story level.”55

Example 3. Brahms, op. 99, movement 1, mm. 51-60.

The firm hand of a narrative agent can also be felt in a passage that might be categorized as a false recapitulation (a designation that already relies on an awareness of narrative manipulation). As can be seen in Example 4, the first subject returns in terms of key, harmony, and melodic outline, but it is drained of gestural immediacy. The roles of piano and cello are reversed: the cello struggles with the piano’s tremolos while the piano sketches the cello’s opening theme in blank dotted half notes. The pianissimo dynamic and dolce marking result in a hushed, almost minimalistic texture. Now little more than an accessory, the cello is deprived of its ability to sing; instead, it is pressed into fulfilling an uncomfortable and unidiomatic harmonic function. Revealingly, the autograph score from which Brahms presumably played at the premiere has simple eighth notes on F written over the awkward left-hand tremolo between F and low C at measure 112 of the cello part (boxed in Example 4) that appeared in the first printed edition. Although it is impossible to reconstruct the sequence of events that lay behind these changes, the tremolo printed in the first edition is unambiguous. By considering an alternative, Brahms seems to have been thinking about performing the sonata from a cellist’s perspective, but he would not ultimately allow such factors to threaten literal consistency within the pages of the printed score.58 In the autograph (see above), the tension between the conflicting demands of composer and performer is made manifest by the way the half-erased tremolo lurks behind the eighth notes written by Brahms’s right hand in order to spare the cellist’s left hand. The proposal and rejection of the alteration again opens up a space between Brahms as composer and performer, suggesting that what he first conceived—and ultimately published—was not necessarily the same as what he expected to hear.

Example 4. Brahms, op. 99, movement 1, mm. 112-18.

Figure 2. Page 5 of Brahms’s autograph score of the first movement of op. 99.

Before returning to this idea, it is worth pursuing the presence of narrative agency into the coda (Example 5), where the tensions that first arose in the exposition are resolved with typically Brahmsian ingenuity and economy. First, the cello finds a middle ground between its opening gestures and the piano’s pre-recapitulatory flattening out of the same theme (mm. 187-88); then, the piano revisits the second subject by way of the subdominant (mm. 193-95). Finally, both are brought together, as the texture and characteristic intervals of the first subject are melded with the thematic outline of the second subject, boxed in Example 6.

Example 5. Brahms, op. 99, movement 1, mm. 187-95.

Dialectical resolution is finally attained: the piano and cello have learned from each other at the prompting of the narrative agent, even though it seems that the cello had more to learn than the piano. But where can we locate—and how can we define—this narrative agent? For Fanny Davies and the audience at the sonata’s premiere, the answer would have been sitting before them in the substantial form of Brahms himself. But how could Brahms’s narrative agency and compositional ego then be distinguished from his agency as a performer?

Example 6. Brahms, op. 99, movement 1, mm. 203-7.

One answer lies in Hatten’s fourth and final type of agent: the “performer-as-narrator,” a persona that reflects the performer’s influence insofar as he or she affects the listener’s perception of other agencies within the work.59 In the case of Brahms performing his own music, then, there is potential for slippage between Brahms as a narrative agent on the one hand and a performer-as-narrator on the other, not to mention his entanglement in the ambiguity between principal and external agency discussed above in relation to the unfolding of the exposition. Brahms, it seems, could shut-de between all these types of agency, showing their borders to be permeable: he could play the role of the piano or the pianist, but at moments such as the false recapitulation (Example 4), he was also uniquely qualified to assume the role of “the composer at the piano,” a role that only he could play on stage but that continues to haunt any performance.

To complicate the matter still further, more discrepancies arise between notions of the ideal performance as mandated by the composer in the score and Brahms’s documented characteristics as a pianist. Although the piano part of the F-Major Sonata is less demanding than the Second Piano Concerto, it still poses formidable technical challenges, and it is reasonable to assume that Brahms must have struck his fair share of wrong notes in performing it with Hausmann. Brahms’s friend Elisabeth von Herzogenberg did not even have to hear Brahms playing his new cello sonata to imagine him “snorting and puffing away” throughout the scherzo; while she imagined the Barthesian “grain” of Brahms’s voice with more amusement than distaste, it seems likely that Brahms’s grunts and snuffles would once again have stood in for the musical gestures that his fingers could only approximate.60

But what of Hausmann’s role? Brahms’s demands on him were perhaps more exacting than on himself, for the cello part of op. 99 is held to be among the most difficult in the repertoire. And yet its difficulty is not immediately audible; it is typical of the awkwardness for which musicians over the years have cursed Brahms under their breath. As we have seen, Brahms paid little attention to matters of comfort and idiom, especially when it came to the publication of finished works. Hausmann might have been granted relief from the unwieldy left-hand tremolo in Example 4, but most subsequent cellists have had to confront it head-on.61 This concession should not cast aspersions on Hausmann’s technical abilities, however, which were of a very high standard, and Brahms knew that he could rely on humility and self-effacement from the cellist.62 Hausmann’s reputation in general and reviews of the premiere in particular suggest that he played with diligence and accuracy, although some critics thought these virtues were delivered at the expense of spontaneity and warmth.63

In the context of their collaboration, Hausmann’s cello provided Brahms with something external that he could nonetheless appropriate. Brahms had briefly taken cello lessons as a young boy, and his orchestral and chamber works show that he was drawn to its potential for long-breathed melodies and ardent expression. But he was loath to give such emotion free rein; throughout his music, moments of melodic plenitude are tempered by formal and structural imperatives. This suggests one reason why the aging Brahms repeatedly turned to Joachim, Hausmann, and the clarinetist Richard Mühlfeld as musical proxies. All three were masters of their instruments, but none had a highly individualistic style, embraced virtuosity “for its own sake,” or overstepped the bounds of good taste.64 A thin line separated sentimentality and gruffness within Brahms’s personality, and playing op. 99 with Hausmann allowed him both to growl and to croon, all the while providing him with an alibi should things get too embarrassingly personal. Thus it seems likely that Brahms sought refuge in Hausmann’s agency even as Hausmann sought to divine Brahms’s.

So what can we make of Brahms and Hausmann’s imagined performance of op. 99, replete with both energetic grunts and tender lyricism? Although it would be fascinating to hear the real thing, I sense that it would also be somehow disappointing, too heavily laden with meaning and authority. I suspect that the nuances of agency raised here would be subsumed by the power of the composer’s immediacy. After all, even today we hardly need encouragement to listen for Brahms’s presence. Extrapolated from the score and repeatedly lionized by analysts and critics as well as performers, his agency is so strong that it threatens to render all other musical personae as puppets, whether they be the protagonists conjured up by his sonata-form dynamics or the dutiful performers charged with playing them.

A comparison of two recordings of the sonata illustrates the extent of Brahms’s control and the drastic measures required to escape it. On their RCA release recorded in 1984, Yo-Yo Ma and Emanuel Ax play with impeccable taste, technique, and musicianship, resulting in a wholly unobjectionable rendition; at times, however, it strikes me as overdetermined, excessively beholden to Brahms’s agenda.65 A brief passage in the scherzo offers a case in point (Example 7).

Example 7. Brahms, op. 99, movement 1, mm. 109-18.

The score here suggests that the cello should dovetail neatly with the piano, and Ma and Ax play it that way. The cellist follows obediently in the wake of the pianist, and the resulting circle of fifths is elegantly satisfying. Jacqueline du Pré and Daniel Barenboim, on the other hand, flagrantly disregard Brahms’s dynamic, rhythmic, and agogic indications in their 1967 recording. Du Pré turns Brahms’s echo into a defiant, impassioned declaration: she stretches time so far that Barenboim’s ensuing hemiolas are in turn relegated to the status of an echo. In Hatten’s terms, du Pré is an unapologetic protagonist as well as a “performer-as-narrator,” whereas Ma and Ax minimize these aspects of their agencies.66 And yet it might be that the reckless scraping of du Pré’s bow is closer to the immediacy and physicality of Brahms’s own “humming and snorting.”

Perhaps the last word, or rather the last gesture, should belong to Robert Hausmann. Despite his sober reputation on the concert platform, Hausmann had a mischievous streak, as another photograph illustrates (Figure 3). Brahms is surrounded by his friends: Hanslick sits next to Brahms on the sofa while Mühlfeld flanks him on the other side. Meanwhile, Hausmann stands behind him, pretending to play the composer like a cello. Hausmann’s cheeky gesture both confirms and belies his role as Brahms’s faithful executant, suggesting that the performer might possess more power than the composer suspects. Brahms is as blissfully unaware of Hausmann’s japery as he is of the recording that du Pré would make seventy years later. In their own ways, both cellists helped illustrate the inexhaustible riches of his music by “playing Brahms” in ways that the venerable composer could not have anticipated.

Figure 3. Brahms and friends, photograph taken by Eugen von Miller zu Aichholz in 1894.

1. Heinrich Schenker, The Art of Performance, ed. Heribert Esser, trans. Irene Schreier Scott (Oxford and New York, 2000), 3. Brahms was reported to have said that Beethoven’s Fidelio and Mozart’s Don Giovanni were best enjoyed not at the theater but at home with the score. Robert Haven Schauffler, The Unknown Brahms: His Life, Character, and Works (New York, 1933), 217.

2. I refer to Hanslick’s famous formulation in his aesthetic tract Vom Musikalisch-Schönen: Ein Beitrag zur Revision der Ästhetik der Tonkunst (Darmstadt, 1991), first published in 1854, according to which the content of music is “sounding forms set in motion” (“tönend bewegte Formen,” 32). Despite his closeness to Brahms, there is no compelling evidence that the latter shared Hanslick’s aesthetic perspective, but Hanslick’s views have been enormously influential on the reception of Brahms’s music nonetheless. The views of both Hanslick and Schenker can be understood within the context of a venerable strain of musical idealism that stretches from Plato to the present by way of the medieval concept of musica universalis (music of the spheres).

3. The cylinder recording is available on a CD issued by the Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, titled Brahms spielt Klavier: Aufgenommen im Hause Fellinger, 1889 (OEAW PHA CD5). On the cylinder’s contents, see Helmut Kowar, “Zum Klavierspiel Johannes Brahms,” in Brahms-Studien 8, ed. Kurt and Renate Hofmann (1990): 35-47; Jonathan Berger and Charles Nichols, “Brahms at the Piano: An Analysis of Data from the Brahms Cylinder,” Leonardo Music Journal 4 (1994): 23-30; Michael Musgrave, “Early Trends in the Performance of Brahms’s Piano Music,” in Performing Brahms: Early Evidence of Performance Style, ed. Musgrave and Bernard D. Sherman (Cambridge and New York, 2003), 302-8; and Jonathan Bellman, “Performing Brahms in the Style hongrois,” in Musgrave and Sherman, Performing Brahms, 329-30.

4. See, for instance, Paul Berry’s insightful and imaginative reconstruction of networks of music and memory (involving Brahms as composer, the singer Julius Stockhausen as performer, and Clara Schumann as listener) that radiate from the song Alte Liebe, op. 72, no. 1, in “Old Love: Johannes Brahms, Clara Schumann, and the Poetics of Musical Memory,” Journal of Musicology 24/1 (2007): 72-111.

5. In this sense, what follows could constitute a first step toward outlining what “carnal musicology” might bring to the study of Brahms: see Elisabeth Le Guin, Boccherini’s Body: An Essay in Carnal Musicology (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 2006).

6. On the questionable authenticity of Brahms’s recollections of playing in Hamburg’s nighttime establishments, see Styra Avins, “Brahms the Godfather,” in this volume; the exchanges between Jan Swafford, Avins, and Boman Desai in 19th-Century Music (Swafford, “Did the Young Brahms Play Piano in Waterfront Bars?” 19th-Century Music 24/3 [2001]: 268-75; Avins, “The Young Brahms: Biographical Data Reexamined,” 19th-century Music 24/3 [2001]: 276-89; and Desai, “The Boy Brahms,” 19th-Century Music 27/2 [2003]: 132-36).

7. Quoted in Michael Musgrave, A Brahms Reader (New Haven and London, 2000), 18.

8. For a comprehensive account of the compositional history of the First Piano Concerto and factors influencing its reception, see George S. Bozarth, “Brahms’s First Piano Concerto op. 15: Genesis and Meaning,” in Beiträge zur Geschichte des Konzerts: Festschrift Siegfried Kross zum 60. Geburtstag, ed. Reinmar Emans and Matthias Wendt (Bonn, 1990), 211-47.

9. Letter of 7 February 1855, in Berthold Litzmann, ed., Clara Schumann und Johannes Brahms: Briefe aus den Jahren 1853—1896 (Leipzig, 1927), 1:76.

10. Eduard Bernsdorf, Signale für die musikalische Welt (9 February 1859), 71-72. Bernsdorf’s reaction was not atypical, as Brahms himself acknowledged: “The first rehearsal roused no emotions whatever among the musicians or the listeners. But for the second rehearsal, no listener showed up and not one musician moved a face-muscle…. I am plainly experimenting and still groping. But the hissing was surely too much?” Letter to Joseph Joachim of 28 January 1859, in Max Kalbeck, Johannes Brahms, rev. ed. (Berlin, 1912-21; repr. Tutzing, 1976), 1:356; trans. in Johannes Brahms: Life and Letters, ed. Styra Avins; trans. Avins and Josef Eisinger (Oxford, 1997), 189.

11. Quoted in Kalbeck, Johannes Brahms, 1:90. To the poet Klaus Groth, Brahms was even more complimentary: “Of course, we are also capable of playing the piano, but none of us possesses more than a few fingers of his two hands.” Quoted in Peter Clive, Brahms and His World: A Biographical Dictionary (Lanham, Md., 2006), 299. Clive’s entry on Liszt (296-301) gives a succinct description of the long and complex relationship between Brahms and Liszt, showing that their mutual respect was genuine despite the aesthetic gulf that divided them.

12. Quoted in Henry Pleasants, ed., Hanslich’s Music Criticisms (New York, 1988), 110.

13. Hanslick, Aus dem Concertsaal. Kritiken und Schilderungen aus den letzten 20 Jahren des Wiener Musiklebens (Vienna: Wilhelm Braumüller, 1870), 255-58; trans. Kevin C. Karnes in “Discovering Brahms,” in this volume.

14. Joseph Viktor Widmann, Johannes Brahms in Erinnerungen (Berlin, 1898), 17-18; trans. by Dora E. Hecht in Recollections of Johannes Brahms by Albert Dietrich and J. V. Widmann (London, 1899), 94.

15. Letter from Brahms to Adolf Schubring of 25 June 1865, in Brahms, Briefwechsel, rev. ed. (Berlin, 1912-22; repr. Tutzing, 1974), 8:205; trans. in Avins, Johannes Brahms, 325.

16. Robert Schumann had written variations on Paganini’s Caprice in 1832 (published in the Études pour le pianoforte d’après les caprices de Paganini, op. 3), but on the appearance of Liszt’s set Schumann generously conceded the palm to the Hungarian. It seems that Brahms had been contemplating approaching Liszt’s network of composers and virtuosos who gathered together under the banner of the New German School since 1860. In a letter to his publisher Melchior Rieter-Biedermann, Brahms bemoaned the fact that the only pianists capable of doing his First Piano Concerto justice were the least likely to take it on: “Almost all of the pianists able to meet its demands belong to the neudeutsch school, which doesn’t tend to bother itself much with my things.” Letter of 29 August 1860, in Brahms, Briefwechsel, 14:48.

17. Quoted in Musgrave, A Brahms Reader, 129-30. In general, Brahms’s increased stature as a composer brought with it a concomitant lowering of his regard for performers. Despite Bülow’s widely recognized qualities as a conductor and pianist and his dedication to Brahms’s music, for instance, Brahms opposed the notion of a statue in Bülow’s honor on the grounds that such memorials should be reserved for composers.

18. Carl Dahlhaus, Nineteenth-Century Music, trans. J. Bradford Robinson (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1989), 138.

19. Charles Rosen, Critical Entertainments: Music Old and New (Cambridge, Mass., and London, 2000), 167-69.

20. The Übungen have recently been issued in a new edition by Johannes Behr with notes on execution by Peter Roggenkamp: Brahms: 51 Übungen für das Pianoforte mit 30 weiteren, größenteils erstveröffentlichten Übungen (Vienna, 2002).

21. Eugenie Schumann reported that Brahms “thought very highly of Clementi’s ‘Gradus ad Parnassum,’” and May also mentioned his reliance on it (quoted in Musgrave, A Brahms Reader, 132-33). Brahms also looked through Czerny’s Große Pianoforteschule, op. 500, at the behest of Clara Schumann in 1880 (see Brahms: 51 Übungen, iii). It is notable that Liszt too turned to the prosaic form of piano exercise later in life. His Technische Studien were assembled between 1868 and 1873, but they were not published until after his death in 1886, and it is doubtful whether Liszt would have sanctioned their appearance in this form.

22. Letter of 12 November 1893, Brahms, Briefwechsel, 12:107. Brahms also warned Clara Schumann that his exercises could “do the hand all manner of damage.” Letter of 22 December 1893, in Litzmann, Clara Schumann und Johannes Brahms, 2:535.

23. May commented on Brahms’s predilection for “forming exercises from any piece or study upon which I might be engaged” rather than relying on the “ordinary five-finger exercises” (quoted in Musgrave, A Brahms Reader, 133). The tendency to conflate work and exercise has reached a new apex (or nadir) with Idil Biret’s recording of the Übungen as part of Naxos’s edition of Brahms’s complete piano music (Naxos 8501201). Taking the reification of Brahms’s music to such a logical extreme results in an uncanny sound-object shorn of meaningful musical context.

24. Over the winter of 1881-82, Brahms took the concerto on a tour that called at eighteen cities throughout Germany, Austria, and the Netherlands, involving no fewer than twenty-one performances. The following winter he took it to seven further cities. For the purpose of these early performances, Brahms entered detailed tempo indications into the autograph; typically, they did not survive into the published edition, which would remain unsullied by the residue of performance. See Robert Pascall and Philip Weller, “Flexible Tempo and Nuancing in Orchestral Music: Understanding Brahms’s View of Interpretation in His Second Piano Concerto and Fourth Symphony,” in Musgrave and Sherman, Performing Brahms, 220-43.

25. George Henschel, Personal Recollections of Johannes Brahms (Boston, 1907), 18. In his letter to Clara Schumann, Brahms was referring to the E-Minor Intermezzo, op. 116, no. 5 (letter of early October 1892, in Litzmann, Clara Schumann und Johannes Brahms, 2:479; trans. in Avins, Johannes Brahms, 698). The difficulties of Brahms’s music generally adhere to Schenker’s exacting criteria: “The composer may not throw in a technical problem merely to show himself and the performer in the pose of a musician easily overcoming difficulties—such pieces are generally written by the virtuoso-composers” (The Art of Performance, 77).

26. Anonymous critic, “Stuttgart,” Allgemeine musikalische Zeitung 16/51 (1881): 810-11.

27. Quoted in Musgrave, A Brahms Reader, 125.

28. Berta Geissmar, The Baton and the Jackboot: Recollections of Musical Life (London, 1988), 8.

29. Quoted in Musgrave, A Brahms Reader, 125. The sympathetic Siegfried Kross contends that the lukewarm reaction to Brahms’s playing was due to the rigors of his tour: he was burned out (Johannes Brahms: Versuch einer kritischen Dokumentar-Biographie [Bonn, 1997], 2:861). However, the tenor and frequency of such criticism suggest that Brahms’s deficiencies were both notable and persistent.

30. Quoted in Robert Philip, “Brahms’s Musical World: Balancing the Evidence,” in Musgrave and Sherman, Performing Brahms, 351. In her memoirs, Eugenie Schumann recalled the “animosity” that was always latent in Brahms’s playing: “I do not believe that Brahms looked upon the piano as a dear trusted friend, as my mother [Clara] did, but considered it a necessary evil, which one must put up with as best one could.” Memoirs, trans. Marie Busch (London, 1927), 170.

31. Quoted in Musgrave, A Brahms Reader, 123.

32. Ibid., 125.

33. Quoted in Detlef Kraus, Johannes Brahms: Composer for the Piano, trans. Lillian Lim (Wilhelmshaven, 1988), 82. Liszt was in a good position to judge: he had asked to see the concerto when he met Brahms at a concert in 1882, and Brahms had been happy to comply (see Clive, Brahms and His World, 301). Liszt’s response to the concerto was polite: “Frankly speaking, at the first reading this work seemed to me a little gray in tone; I have, however, gradually come to understand it. It possesses the pregnant character of a distinguished work of art, in which thought and feeling move in noble harmony.” (Quoted in Karl Geiringer, Brahms: His Life and Work [New York, 1982], 150.) Liszt even tried to arrange a performance of the concerto in Zurich, but the orchestral parts were unavailable (see Clive, Brahms and His World, 301).

34. Quoted in Musgrave, A Brahms Reader, 124.

35. Richard Specht, Johannes Brahms, trans. Eric Blom (London, 1930), 306-7. See also Schauffler’s description of Brahms’s noises in “Brahms, Poet and Peasant,” Musical Quarterly 18/4 (1932): 555.

36. See Roland Barthes, “The Grain of the Voice,” in Image, Music, Text, trans. Steven Heath (New York: 1977), 179-89.

37. Quoted in Walter Niemann, Brahms, trans. Catherine Alison Phillips (New York, 1929), 319. Henschel reported that Brahms claimed to be able to tell the gender of a pianist by ear alone (Personal Recollections of Johannes Brahms, 41). Brahms affected to be contemptuous of women pianists: “I have a powerful prejudice against [them] and anxiously avoid listening to them.” (Letter to Ferdinand Hiller of November 1876; trans. in Avins, Johannes Brahms, 502.) His respect for Clara Schumann tells a different story: she had performed the First Piano Concerto as early as 1861, which perhaps reveals as much about the differences between the two concertos as about the various forms of Brahms’s misogyny. In any case, Florence May and Clara Kretzschmar (wife of the famous critic Hermann) flew in the face of Brahms’s sexism by performing the Second Piano Concerto in 1888 and 1891, respectively.

38. Letter of 7 July 1881, in Brahms, Briefwechsel, 13:102-3, trans. in Avins, Johannes Brahms, 580.

39. Quoted in Pascall and Weller, “Flexible Tempo and Nuancing in Orchestral Music,” in Musgrave and Sherman, Performing Brahms, 232. Specht’s emphasis on Brahms’s self-immersion echoes Hanslick’s critique of Brahms’s Viennese debut.

40. Quoted in Musgrave, A Brahms Reader, 125.

41. Marie’s remark was recorded by her sister Eugenie: “To hear Brahms play his own things was not always satisfying, but highly interesting nonetheless. Marie once described his playing of his B-flat-major Concerto as a ‘spirited sketch.’” (Quoted in Ulrich Mahlert, Brahms: Klavierkonzert B-Dur op. 83 [Munich, 1994], 125.) The English pianist Fanny Davies also described Brahms’s playing as “rugged, and almost sketchy.” (Quoted in Bozarth, “Fanny Davies and Brahms’s Late Chamber Music,” in Musgrave and Sherman, Performing Brahms, 172.)

42. Quoted in Swafford, Johannes Brahms (New York, 1997), 469. Hugo Wolf’s review struck a predictably sour note amid the chorus of approval (in Richard Batka and Heinrich Werner, eds., Hugo Wolfs Musikalische Kritiken [Leipzig, 1911], 113-14).

43. Anonymous critic, “Tagesgeschichte. Musikbriefe. Berlin,” Musikalisches Wochenblatt 15/9 (21 February 1884): 111-12.

44. Niemann, Brahms, 319.

45. Quoted in Clive, Brahms and His World, 3.

46. On the myriad relationships between soloist and orchestra to which concertos can give rise, see Joseph Kerman, Concerto Conversations (Cambridge, Mass., and London, 1999).

47. See Kalbeck, Johannes Brahms, 4:33. Brahms went on to write the Piano Trio in C Minor, op. 101, and the Double Concerto, op. 102, with Hausmann in mind. For an overview of Brahms’s relationship with Hausmann, see Friedrich Bernhard Hausmann, “Brahms und Hausmann,” Brahms-Studien 7 (1987): 21-39.

48. Quoted in Bozarth, “Fanny Davies and Brahms’s Late Chamber Music,” in Musgrave and Sherman, Performing Brahms, 173.

49. Robert S. Hatten, Interpreting Musical Gestures, Topics, and Tropes: Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert (Bloomington and Indianapolis, 2004), 225-26. Since the ensuing discussion relies on Hatten’s categorization of agency, I shall quote his definitions of them where relevant. The cello and piano here correspond to Hatten’s Type 1 and Type 2 agents, respectively: “Type 1. Principal agent (actant, protagonist, persona, subject, voice): the individual subjectivity with which we identify, whether as performer or listener. Type 2. External agent (negactant, antagonist; or depersonalized external force, e.g., Fate, or Providence): that agency which acts upon, or against, the principal agent.” For an alternative perspective on issues of musical agency, see Eero Tarasti, Signs of Music: A Guide to Musical Semiotics (Berlin and New York, 2002), 140.

50. Margaret Notley discusses op. 99 in this context in Lateness and Brahms: Music and Culture in the Twilight of Viennese Liberalism (Oxford and New York, 2007), 76-80.

51. For a comprehensive overview of Brahms’s application of this compositional technique, see Walter Frisch, Brahms and the Principle of Developing Variation (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 1984).

52. Kalbeck was the first to note the resemblance, along with that between the main theme of the sonata’s finale and “Wir hatten gebauet,” the student song Brahms quoted in the Academic Festival Overture, op. 80 (Johannes Brahms, 3:35).

53. The piano’s dominance here is foreshadowed by the way it wrests control of the bass line in measure 31, taking advantage of the cello’s inability to go any lower.

54. It is telling, however, that C major makes a brief attempt to reestablish itself via the piano in measure 57. This time, roles are reversed: the cello’s harsh diminished fifth on the third beat of the measure pushes proceedings back toward E minor.

55. Hatten, Interpreting Musical Gestures, 226. The narrative agent constitutes Hatten’s third type, and is distinguished from types 1 and 2 (which are embedded in a musical “story”) through its concern with “a compositional play with musical events or their temporal sequence or relationship, inflecting their significance, or proposing a certain attitude toward them. This agency…provides a ‘point of view’ or filtered perspective…. The narrative agency is cued by shifts in level of discourse.”

56. See also the opening of the slow movement, where the traditional roles of piano and cello are similarly reversed: the cello plods while the piano attempts an impossible crescendo (mm. 1-4).

57. See Notley, “Brahms’s Chamber-Music Summer of 1886: A Study of Opera 99, 100, 101, and 108” (Ph.D. diss., Yale University, 1992), 280-82, for details of this alteration (and others).

58. Brahms made a similar amendment in mm. 56-57 of the piano part, where broken chords that were broad handfuls in the autograph became hair-raisingly difficult in the first edition for the sake of slightly more elegant voicing. (See ibid., 278.)

59. Hatten, Interpreting Musical Gestures, 226. The performer-as-narrator directs “the listener’s attention (possibly overdidactically) to the structure and significance of events…. Commenting upon the events from the perspective of the individual point of view and prejudices of the performer as engaged participant in the ‘telling’ of the story. May (over-) emphasize the characterization of actants (Types 1 and 2), or (rhetorically) mark especially unusual (narrative) reorderings or disruptions of expected events or event sequence (Type 3).”

60. “I’d like to hear you play the scherzo, with its driving power and energy—I always hear you snorting and puffing away at it! Nobody else will ever do it justice as far as I’m concerned.” (Letter of 2 December 1886, in Brahms, Briefwechsel, 2:131.)

61. Not all, however. On her EMI recording with Daniel Barenboim (Brahms Cello Sonatas, originally released on LP in 1967, digitally remastered and rereleased on CD as EMI 0724356275829), discussed in further detail below, Jacqueline du Pré takes the C an octave above the notated pitch. Perhaps she was using an edition such as that by Leonard Rose (New York, 1956), which tacitly transposes the C up an octave.

62. For an account of Hausmann’s personality and musical style, see M. R., Some Points of Violin Playing and Musical Performance as Learnt in the Hochschule für Musik (Joachim School) in Berlin During the Time I Was a Student There, 1902-1909 (Edinburgh, 1939), 83-102.

63. Notley quotes a review of the premiere by Robert Hirschfeld: “The cellist Hausmann pushes…objectivity as far as the mortification of feeling.” (“Brahms’s Chamber-Music Summer,” 24.) She also cites Theodor Helm’s tepid reaction: “Even then we had to commend the artist on his truly classical playing, acquired in the very best school, while we also, nevertheless, did not fail to notice his lack of temperament and a certain academic-professorial bearing” (25). Wolf similarly complained that Hausmann’s playing was “cold, affected, and (in our opinion) boring.” (Review of 28 November 1886 in the Wiener Salonblatt, in Hugo Wolfs Kritiken im Wiener Salonblatt, ed. Leopold Spitzer and Isabella Sommer, [Vienna, 2002], 1:170-72.) Hausmann’s scholarly self-effacement reminds us that types of agency may impinge on the performance of work even if they do not stem directly from the interpretation of the score: the cellist’s disinterested approach to the work may have encouraged concertgoers to perceive him as a narrative agent—or even an agent of Brahms’s agency!—rather than a protagonist.

64. On Joachim’s musical personality, see J. A. Fuller Maitland, Joseph Joachim (London and New York, 1905); on Mühlfeld’s, see Colin Lawson, Brahms: Clarinet Quintet (Cambridge and New York, 1998), 32-33.

65. Yo-Yo Ma and Emanuel Ax, Brahms Cello Sonatas (RCA Victor Red Seal 59415, 2004). Their re-recording of the sonatas for Sony (48191, 1992) comes across with greater flair, but retains many of its predecessor’s fundamental characteristics.

66. Du Pré’s agency as a protagonist and performer-as-narrator (Hatten’s types 1 and 4) is so powerful that at times her performance seems to cast the sonata itself as an externalized type 2 agent (a negactant or antagonist).