Heinrich Schenker’s review of Brahms’s choral pieces, op. 104 (1889), appeared in serialized form across three issues of the Leipzig Musikalisches Wochenblatt in August and September 1892. It was the third published essay by a writer who would go on to become one of the most influential music theorists of the twentieth Century. In this review, we find few hints of the sorts of analytical work for which Schenker (1868–1935) would later become famous—though as Allan Keiler has pointed out, there are indeed a few hints.01 Nonetheless, we encounter a young composer and critic whose passion for analysis had already been stoked by his sense that in Brahms’s music, unique among that of living artists, one hears traces of a glorious German musical tradition stretching backward in time through Beethoven and Mozart to Johann Sebastian Bach. Indeed, for Schenker to remark as he did on Brahms’s Nachtwache II (op. 104, no. 2) that “one might suspect J. S. Bach” if Brahms’s name were not appended to the title page was, for the critic, to bestow upon Brahms the highest praise imaginable.

In this review, we witness the twenty-four-year-old Schenker engaging in excited, sometimes breathless discussions of Brahms’s mastery of melodic construction and of the moods conjured by his melodies. We also encounter Schenker’s Wagner-like fascination with music’s ability to express the emotional significance of poetic texts more vividly than words alone can, and with the power of motivic development and replication to mirror the dynamic complexities of human thought and feeling. Throughout, Schenker’s discussion is deeply rooted in a German hermeneutic tradition that evolved from the work of the philosopher and theologian Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768–1834) and pervaded the Romantic discourse on the arts. His technical descriptions of the music’s unfolding are accompanied, at nearly every stage, by attempts to describe the meaning of that music and the probable creative intentions of the composer.02

Though Schenker and Brahms crossed paths occasionally during the latter’s final years, the two were hardly on intimate terms. After 1900, Schenker’s analytical and theoretical work would take him far afield from the sorts of interpretive statements and strategies explored in this early essay, but his deep respect and fondness for Brahms’s music remained unchanged to the end. Schenker’s review originally appeared as “Kritik. Johannes Brahms. Fünf Gesänge für gemischten Chor a capella, Op. 104,” Musikalisches Wochenblatt 23 (1892): 409–12, 425–26, 437–38. It is reprinted in Heinrich Schenker als Essayist und Kritiker. Gesammelte Aufsätze, Rezensionen und kleinere Berichte aus den Jahren 1891–1901, ed. Hellmut Federhofer (Hildesheim, 1990), 14–26. All endnotes are editorial.

There are six voices in the choir: soprano, first and second altos, tenor, first and second basses. The melodic construction makes clear that its invention was inspired from the start by an antiphonal exchange:

“Soft tones of the breast, awakened by the breath of love”

The deliberate retention of the antiphonal structure—the whole choir comes together only to express the point “Trag ein Nachtwind euch seufzend in meines zurück” (Let a night wind bear you back, sighing, to mine) and four measures before the end—enables the choir to represent, as it were, two individuals, embodied in the soprano and the tenor. The other voices exhibit little individuality in a melodic sense and, functioning harmonically, merely support the melody. This homophonic texture, embedded within the antiphonal structure (this arrangement is probably to be regarded as the most extreme concession to the element of individuality in the poem that the choir could possibly make), corresponds marvelously to the idea of the distich. That is, if one will give me the right to assert that the thin layer of reflection spread over the poetic content refers to a single individual of a particular intellectual disposition, then the homophonic texture in the choir seems, at the very least, quite justifiable.

Leise Töne der Brust, Geweckt vom Odem der Liebe, Hauchet zitternd hinaus, Ob sich euch öffn’ ein Ohr, Öffn’ ein liebendes Herz, Und wenn sich keines euch öffnet, Trag’ ein Nachtwind euch Seufzend in meines zurück. |

Soft tones of the breast, awakened by the breath of love, whisper forth tremulously if an ear or loving heart should open to you; and should none open, let a night wind bear you back, sighing, to mine3. |

Not every lover knows how to express his “soft tones of the breast.” And if one such expression takes on the unique character of the individual who utters it, then it cannot possibly be the case that several individuals can evoke this same character in their own utterances, otherwise that character would lose its uniqueness as such. Thus it seems to me that the poetic idea must exclude the possibility of polyphony in the choir. For the most part, Brahms holds himself to a homophonic framework in this piece. And for the reasons just discussed, I would chastise him for tending toward polyphony in a few spots, in contravention against the poetic idea—as we find when he sets “whisper forth tremulously,” “if a loving heart should open,” etc. Furthermore, the system of two individuals, each represented in a homophonic manner (about which I spoke above), seems to me to reveal an independent idea on the part of the composer, going beyond the idea of the poet. It is like two lovers who have not yet confessed their love for each other, but who, separated by a great distance, dedicate to each other their “tones of the breast awakened by the breath of love.” It is as if their tones and sighs cross paths in the air that separates them. One will consider this impression of mine a mere hypothesis in which I, for my part, find an explanation for the two individuals. Without it, the division of the choir would remain inexplicable to me, since the content of the poem seems by nature to revolt against it.

Since Brahms perceived the poetic content like an event unfolding before him and acknowledged the driving force of feeling that gradually implanted into the scene (so to speak) the idea of things following each other in time, so he responded to these hints, rooted in reality, in the form of tone painting—a tone painting that seems, as it were, motivated directly. And so, for instance, we find the musical setting of “hauchet zitternd hinaus”:

“whisper forth tremulously”

and the words “trag ein Nachtwind euch seufzend, seufzend”:

“let a night wind bear you back, sighing, sighing”

The intensification of feeling, with the crescendo building to forte, becomes readily perceptible with the words Ob sich euch öffn’ ein Ohr (if an ear should open). But I wonder whether Brahms could not compel the psychological sense of time to overcome the form of the poem at the words Öffn’ ein liebendes Herz (if a loving heart should open). In spite of the pentameter and in spite of the hexameter, these words belong together with those that came just before them, and certainly within the context of the same intensification of feeling. And so, a forcible separation, as we hear it, cannot be carried out. So why was it?

Nonetheless, this piece must be considered worthy on account of its absolute musical beauties, which I could regard somewhat one-sidedly, and even more so because of the truthfulness of its fundamental mood, which is that of its creator in the best sense. Finally, it is worth noting that Brahms has set this same distich as a four-part canon for women’s voices (op. 113, no. 10).

A six-part choir (soprano, first and second altos, tenor, first and second basses), and a masterwork down to the smallest cell! If the melody and harmony did not give Brahms away immediately, one might suspect J. S. Bach in the free and meaningful polyphony, in the powerful solemnity, and in the broad rush of harmonies.

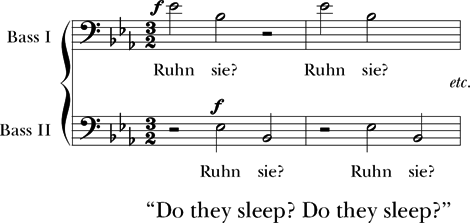

In brilliant ways, Brahms mixes, in the first part of the piece, epic and lyrical elements when he foists upon the united choir of soprano, altos, and tenor—which declares to us its impression, already emerged into feeling: “Ruhn sie? rufet das Horn des Wächters drüben aus Westen” (Do they sleep? Thus calls the horn of the watchman from the West)—the motive of the watchman, proclaimed in the basses, as if under the pretext of actuality:

“Do they sleep? Do they sleep?”

And so the world of mood floats above the world of reality. Especially remarkable in this respect is the composer’s determination that mood take priority over tone painting in the horizontal line. Even more remarkable, perhaps, is the way in which Brahms has portrayed, through rhythmic means, the form of the question, “Ruhn sie?…rufet das Horn”:

“Do they sleep? Do they sleep? Thus calls”

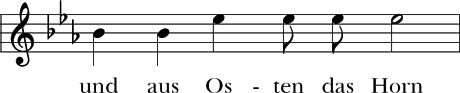

And now, when the horn “aus Osten” is heard and “Sie ruhn!” answers back, the melody turns, as if instinctively, in the opposite direction:

“and from the East, the horn”

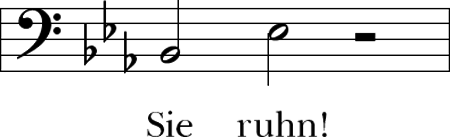

And again one hears, in the second bass and tenor, and finally in the second alto, the motive of the horn in the affirmative form of the inverted leap of a fourth, like an element of reality emerging from out of the fabric of mood!

“They sleep!”

The first part comes to a close without having changed the fundamental tonality (E-flat major). In this way, I believe, the nature and character of the inversions, which have played such a significant role in this setting, have been made more conspicuous in the best sense of the word, and have been brought more closely in line with the feeling. But one must admire the consequences of this aspect of construction even more when one looks at one of the means by which Brahms does justice to the relationship between the two distiches of the poem: between the one that is inquiring and the one that is responding. In order to set the inquiring first distich before the responding one (namely, the second, as indicated by both mood and idea) in the most effective way possible, Brahms strove, using every means at his disposal, for vivid uniformity and energy in the first distich, which is precisely the consequence of the E-flat-major tonality.

Ruhn sie? rufet das Horn des Wächters drüben aus Westen, Und aus Osten das Horn Rufet entgegen: Sie ruhn! |

Do they sleep? Thus calls the horn of the watchman from the West, And from the East, the horn answers back: They sleep! |

Hörst du, zagendes Herz, Die flüsternden Stimmen der Engel? Lösche die Lampe getrost, hülle in Frieden dich ein |

Do you hear, timorous heart, the whispering voices of angels? Extinguish your lamp confidently, and let peace envelop you |

In the second part of the piece, one hears—just as readily and likewise psychologically motivated—A-flat major, C-flat major, and A-flat minor taking turns, until E-flat major once again asserts its hereditary right to rule, so to speak.

And now one wonders and takes pleasure in all the wonders and pleasures that be! At the boundary between the two large sections of the work, it is necessary to color and strengthen the organism of moods and thoughts, and even, in a certain sense, to call it newly to life. At this moment, Brahms lets the choir sink from forte to piano, with the words “They sleep!” at the end of the first section. He lets the new idea enter at this piano, thus letting go of the tone that concluded the old mood and bringing in the new one! Is it not, at this point, as if the moods and thoughts meet each other in the midst of the stillness of the piano? And doesn’t some sense of the earlier harmony almost seem to live on in this new tone?

Then, the voices enter one after the other, as if each wanted to ask, “Do you hear, timorous heart”? And they come together to complete the question with the words “the whispering voices of angels.” The melody of this short, three-measure phrase is closely related to the preceding section, as I will show below.

The way the passage loses itself in the key of A-flat major (I say loses itself because of its gentle gliding over the C-minor triad, and because of the F triad that saturates the first part of the second measure); the rhythm and the sequence of harmonies, and especially the placement of the tonic and dominant triads together; the melodic line at the word voices and the dynamic intensification of the melody to a gentle height with this word—how willingly all of these elements are bound together in order to serve the poetic idea, which seeks to capture and hold down, as it were, a more remote thought with the gentle strength of the mood. All of these things are furthermore united in order to satisfy the form dictated by the poet, with its fine and soft questioning, just like that of his own imagination!

The magic of this mood disappears very quickly, and a new idea, more clearly based in actuality, makes its appearance. But Brahms, with the most perfectly characteristic will, as if he served that of the poet alone, lifts this idea up into a transfiguring light. In groups and individually, the voices call one after another: “Extinguish your lamp confidently.” The warmth and depth of a happy confidence emerge, and all the voices sing, softly but with full strength, “let peace envelop you.”

Already [we observe] the brilliant use of the G in the first group of voices, which leads us, for the very first time, into the free world of polyphony and reveals, all at once, the so peculiarly beautiful C-flat-major tonality! To be sure, the motive that appears with the words “extinguish your lamp confidently” is hardly new.04 But what freedom in the transformation of the leap of the fourth, with its gradual augmentation in the soprano! New motives and melodies bring us the words “let peace envelop you” in both free and strictly imitative figures that chase each other in the lively voices. But here one also hears, clearly and frequently, the old motive of the horn resounding throughout in the form of the answer (especially in the two basses), as if it wanted to set us, once again, firmly upon the floor upon which we stood earlier.

in the first group of voices, which leads us, for the very first time, into the free world of polyphony and reveals, all at once, the so peculiarly beautiful C-flat-major tonality! To be sure, the motive that appears with the words “extinguish your lamp confidently” is hardly new.04 But what freedom in the transformation of the leap of the fourth, with its gradual augmentation in the soprano! New motives and melodies bring us the words “let peace envelop you” in both free and strictly imitative figures that chase each other in the lively voices. But here one also hears, clearly and frequently, the old motive of the horn resounding throughout in the form of the answer (especially in the two basses), as if it wanted to set us, once again, firmly upon the floor upon which we stood earlier.

Now I will address the melodic construction. Indeed, it is this that lends the work a sense of Romantic magic by virtue of its unique quality, and in whose womb the seeds of all the harmonic gestures that lend the piece its distinct physiognomy grow. Take a look at the following structures:

“Thus calls the horn of the watchman from the West”

and

“Do you hear, timorous heart, the whispering?”

Characteristic of both is the interval of a second, which pushes its way into the purely harmonic series of tones without destroying its own harmonic sense.

At the end, the melodic construction of the soprano is as follows:

“let peace envelop you”

How characteristic is its descent into the depths, and the elementary decomposition of the triad in measures 3 and 4!

Finally, I ought to comment upon the contributions made to the effectiveness of the piece by rhythm and harmonic structure. But who can assess these? One will permit me merely to remark, in a descriptive way, upon a few things related to this issue. In the first four measures, the tonic triad appears on the first beat and the dominant triad on the third. In the next two bars, the subdominant triad usurps the place of the dominant in order to make way for the close of the first section of the piece in its proper place. Eight measures before the end, we have a C-flat-major triad on the downbeat, an A-flat-minor triad on the second beat, and an E-flat-major triad on the third. But seven measures before the end (that is, in the very next bar), the first two beats of the measure are dominated by a B-flat-major triad functioning as the dominant of the E-flat-major chord reached on the third beat. And it is precisely this latter sonority that will, in its own key, usher in the future! A crisis of melody, dynamics, ideas, and tonality occurs on this third beat of the measure. And what a brilliant accomplishment this is! Like an aftereffect of this crisis, the E-flat-major (tonic) triad is permitted to occupy, once again, the third beat, while the subdominant takes the first for itself. Only later does the tonic push its way forward, until it reaches the one place that truly reflects its significance.

And the amazing work that I’ve just described is only twenty-one bars long!!!

The most remarkable thing about this six-part choral work is the freedom with which the poetic idea has created its own musical form corresponding precisely to itself. As in the poem, the brightness and gentleness of the Frühlingsträume (dreams of spring) oppose the serious shadow of the autumnal, and the delicate, graceful energy of the color represented by “der bei den späten Hagerosen verweilende Sonnenblick” (the ray of sun lingering on the late, wild roses) is tinted by the sweet-sad melancholy of “eines letzten, hoffnungslosen Glückes” (a last, hopeless bliss). The music vividly portrays these contrasts through means peculiar to it. A perfect congruence is apparent in the ordering of the four tonalities that govern the work: F minor and A-flat major, F major and F minor. The melody is likewise divisible into four groups, which only increases the vividness of the ideas expressed. One will allow me to say the following about the motivic replications and repetitions appearing in the melody. In one’s experience of a mood imparted through the senses or only indirectly through the imagination, opposing feelings seem to combat each other, but in reality one feeling exerts a lasting effect upon the next. Ultimately, all of these feelings work together, contributing to the overall character of the mood. In order to re-create the complicated nature of a mood that one will readily consider “unified,” motivic replications and repetitions, if operating in the service of ideas, can function like materials for binding together skillfully assembled thought constructions, since they can replicate certain effects of one idea within opposing ones. It is possible (ultimately every individual must decide for himself) that the partial repetition of the first melodic group in the fourth part of our piece portrays perfectly the idea of the “letztes Glück” (last bliss), since it implies a connection with the image, “leblos gleitet Blatt um Blatt still und traurig von dem Bäumen” (lifelessly, leaf after leaf glides quiety and sorrowfully from the trees). It is equally possible that similarities in the melodic construction of the two middle sections also bring these closer together, with symbolic strength, so to speak. All of this is possible within the mind of each individual, even if it goes beyond the intentions of the composer, who would perhaps claim only a formal function for the similarities and repetitions in his melodic construction, as one generally does in purely instrumental music. It is indeed tone painting when “leblos gleitet Blatt um Blatt” is rendered musically in this way:

“Lifelessly, leaf after leaf glides”

There are five voices in the choir: soprano, alto, tenor, and two basses. This five-voice texture is required by the canon, which appears between the soprano and the alto one time and between the first bass and the soprano another. The other voices content themselves with interpreting the canon in a clear and unambiguous manner. The idea of a canonic setting is not required by the poem, however. Rather, it is a spontaneous musical luxury.

Within the canon, there are motives of a typically Brahmsian type:

“My youthful days, where have you gone so quickly?”

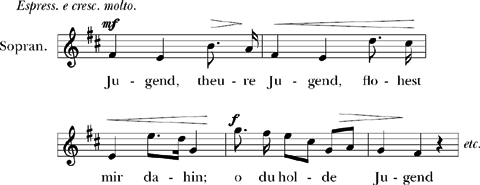

The poet’s broad apostrophe to youth—a warm apostrophe indeed—lifts the composer from the D-minor tonality of the canon upward to D major, but carries him well beyond the usual convention of symmetry. And so we have the following turn, a characteristic expression of Brahms’s melodic style:

“Youth, precious youth, you have fled from me”

I consider the close of the D-major section to be Schubertian:

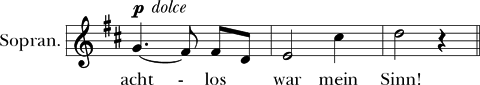

“unheeding was my mind!”

The clarity of the melody and the plasticity of its structuring are heightened by the dynamics, which aid the composer with their manner of rising and falling.

Brahms has provided the tempo indications lebhafte, doch nicht zu schnelle (lively, but not too fast) for the first section of the piece and ein wenig gehaltene (a tad restrained) for the second. The latter should be regarded as an intensification of the former rather than its opposite. To me, the most characteristic aspect of the composition is revealed in these indications. For it seems to me that the composer has not found an expression of heavy resignation in the poem. Rather, it seems that he saw both a picture and the mood of a mature personality, whose seriousness is only the result of self-reproach on account of his “achtlos verlorene Jugend” (unheeding, lost youth). To my mind, what is expressed in this piece is more like the fleeting nature of a thought than the persistence of a deeper mood.

On its own, the music is pure Brahms. One could include it on a program with a hundred other compositions, and it would declare “who my master was.”

If our master is inspired by thoughts of transience and eternity as they verge upon him, so too those thoughts seem to intensify his strength to an unusual degree. Though I may be having unwelcome visions, it seems to me that they wish to reveal their own immortality to him. So long as the poem draws nourishment from this most powerful stuff that depresses us all (transience), Brahms casts a pall of tones over the poem without shedding a tear. But when the last strophe arrives with its narrower, pettier, even feeble content, it seems to me that Brahms loses his inspiration. Brahms (a serious reader) divides the poem into six strophes of four lines each. In these strophes, the first phrases always depict the most general image, and the subsequent phrases reveal the content—the source or cause of the mood and image—in greater detail. Look at how Brahms portrays the relationship between the first phrases and subsequent ones:

“Gloomy is autumn. And when the leaves fall”

Or, in another place:

“Man becomes humble. He sees”

How clearly does the fifth scale degree in the melody hint at the note that follows, and yet the phrase ends in such a resolute way! Elsewhere, we encounter a motive with this characteristic rhythm:

“the heart also sinks”

which, at the same time, superbly serves the cause of psychological truth in its inversion:

“he foresees the end of life, as of the year”

The soprano retains the lead throughout. But at times the other voices go beyond mere harmonic commentary insofar as they acquire a distinct, characteristic sense of their own, in imitation of a motive related to the image portrayed. (See the middle voices in measures 3 and 4, 8 and 9, 11–16, etc.) The soprano also has occasional painterly moments, as with the words “nach dem Süden wallen” (migrate southwards) and “Blinken entströmt” (gleaming pours forth). The light of a mild, reconciled sort of wisdom seems to have illuminated Brahms’s feeling when he thought of the man “der die Sonne sinken sieht, des Lebens, wie des Jahres Schluss ahnt” (who sees the sun set and foresees the end of life, as of the year). What quiet dignity greets the C-major tonality, entering as C minor departs! In contrast, the music expressing the point of “des Herzens seligster Erguss” (the most blessed outpouring of the heart) seems to me to slide downward from the heights. This is where Brahms, to my mind, placed himself before the greatness of his great conception and his great music, in relation to which my own impressions can and must orient themselves. Incidentally, Brahms is right; such a powerfully thinking and powerfully feeling man cannot possibly portray and dissolve such a rich and substantial mood in a tear.

See Allan Keiler, “Melody and Motive in Schenker’s Earliest Writings,” in Critica Musica: Essays in Honor of Paul Brainard, ed. John Knowles, 188–91 (Amsterdam, 1996).

On Schleiermacher’s contributions to hermeneutics and their applications in nineteenth-Century music criticism and analysis, see Ian D. Bent, ed., Music Analysis in the Nineteenth Century (Cambridge, 1994), 2:2–8. For a discussion of the Wagnerian qualities of Schenker’s review, see Kevin C. Karnes, Music, Criticism, and the Challenge of History: Shaping Modern Musical Thought in Late Nineteenth-Century Vienna (Oxford and New York, 2008), chap. 3.

My translations of the poetic texts are based upon those by Lionel Salter, published with the recording Brahms: Choral Works, Philips, CD 432 512–2, 1992.

At this point, the published text refers the reader to the line “and from the East the horn,” rather than to “extinguish your lamp confidently.” However, Schenker’s discussion makes clear that this is a mistake. The G to which Schenker refers appears in measure 13, and the C-flat-major triad in measure 14; the text “extinguish your lamp confidently” appears in measure 13, with the G. At this point, the soprano’s melodic line is, as Schenker observes, indeed not new. It is a transposition of the soprano line at measure 5, which sets “and from the East the horn”—thus, a possible cause for the error. I have corrected this mistake in the translation.