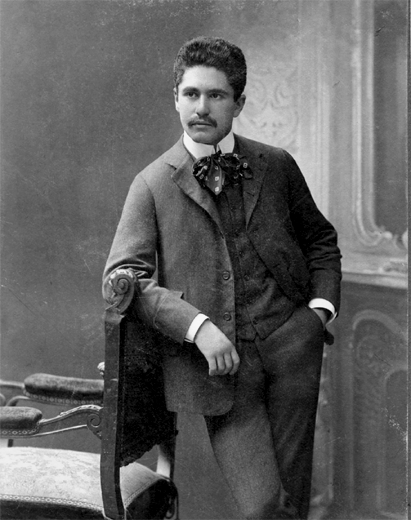

Alexander von Zemlinsky (1872–1942) was one of the most talented and promising young Viennese composers of the turn of the century. After an auspicious study period at the Vienna Conservatory, he went on to have a distinguished career as a teacher, conductor, and opera composer. Among his pupils were Alma Schindler (later to become Mahler’s wife) and Karl Weigl. Zemlinsky was the first and only teacher of Arnold Schoenberg; the two friends also became brothers-in-law when Schoenberg married Zemlinsky’s sister Mathilde in 1901. Weigl (1881–1949) was a prominent conservative Viennese composer and teacher, who served as Professor of Theory and Composition at the Vienna Conservatory after World War I. Zemlinsky and Weigl were among the many Jewish artists who fled to the United States with the advent of the Nazis. Neither found here the kind of respect and acclaim they had experienced in Europe in the years before World War II. These reminiscences appeared in the Viennese journal Musikblätter des Anbruch 4 (1922): 69–70. All endnotes are editorial.

When I think of the time during which I had the fortune to know Brahms personally—it was during the last two years of his life—I can recall immediately how his music affected me and my colleagues in composition, including Schoenberg. It was fascinating, its influence inescapable, its effect intoxicating. I was still a pupil at the Vienna Conservatory and knew most of Brahms’s works thoroughly. I was obsessed by this music. My goal at the time was nothing less than the appropriation and mastery of this wonderful, singular compositional technique.

I was introduced to Brahms at the occasion of a performance of a symphony of mine, which I had composed as a student.1 Brahms had been invited by my teacher Fuchs.2 Soon thereafter, the Hellmesberger Quartet performed a string quintet of mine, which Brahms also heard.3 He asked for the score and then invited me to call on him; he did so with a brief and somewhat ironic remark, casually tossed off: “Of course, come if it might interest you to talk to me about it.” This cost me a hard struggle: the idea that Brahms would speak to me about my attempts at composition elevated my already powerful respect to the level of anxiety. To talk with Brahms was no easy matter. The question-and-answer was short, gruff, seemingly cold, and often very ironic.

He went through my quintet at the piano with me. At first he would offer corrections gently, looking carefully at this or that spot. He never really offered praise, but would grow more animated, and ever more passionate. And when I timidly sought to justify a passage in the development section that seemed to me to be really successful in a Brahmsian spirit, he opened up the string quintet by Mozart and explained the consummate qualities of this “still unsurpassed mastery of form.”4 And it sounded self-evident when he said, “That’s how it’s done from Bach up to myself.” Brahms’s ruthless criticism had put me in an extremely despondent mood, but he soon cheered me up again. He asked about my financial situation and offered me a monthly stipend so that I could work fewer hours and devote myself more to composition. Finally he recommended me to his publisher Simrock, who also agreed to issue my first compositions.5

Alexander von Zemlinsky

From then on my works fell even more than before under the influence of Brahms. I remember how even among my colleagues it was considered particularly praiseworthy to compose in as “Brahmsian” a manner as possible. We were soon notorious in Vienna as the dangerous “Brahmins.”

Then came a reaction, of course. With the struggle to find oneself, there was also an emphatic repudiation of Brahms. And there were periods when the reverence and admiration for Brahms metamorphosed into the very opposite. Then this phase of undervaluation gave way to a quiet reassessment and enduring love of Brahms’s work. And when today I conduct a symphony by him or play one of his splendid chamber works, then I fall once again under the spell of the memory of that time: each measure becomes a personal experience.

—Alexander von Zemlinsky

When in my earliest student years I saw Brahms in person for the first time, I knew very little of his music. But the powerful head, surrounded by snow-white hair and a beard, and at that time not yet drawn by the hand of death, left an indelible impression on me. I experienced for the first time the thrill aroused by being in proximity to an immortal.

It took much time and labor before I could make his work my own. I was accustomed to the sensuous power of Mozart and Schubert and the forcefully blazing rhythms of Beethoven. The language of Brahms seemed to me strange and cold. When I finally succeeded—chiefly through his splendid lieder and his chamber works—in gaining entry to this world that had previously been closed, he became one of my great teachers.

It is not my task here to say how and how much my works were influenced by him. This much I must say, however: that I owe to him purity of compositional technique and seriousness of thematic work, and, not last, a new insight into the masters with whom he himself had studied—Haydn, Mozart, Handel, Bach, and the older vocal composers.

Karl Weigl

Today, direction and desire lead far away from the paths that Brahms trod with manly seriousness. Yet now as then I remain in awe of the spiritual and ethical loftiness of this great master, for whom his art truly meant more than “a play with sounding forms,”6 who was like few others relentlessly self-critical and was at once a believer and a savior.

—Karl Weigl

1.The occasion of the meeting was actually the premiere of Zemlinsky’s Orchestral Suite at a concert at the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde on March 18, 1895. Brahms led his own Academic Festival Overture on the same program. The event is described vividly in Max Kalbeck, Johannes Brahms, rev. ed. (Berlin, 1912–21: repr. Tutzing, 1976), 4:400–401.

2.Johann Nepomuk Fuchs (1842–99), Austrian composer, conductor, and from 1888 Professor of Composition at the Vienna Conservatory.

3.The String Quintet in D Minor (unpublished), performed on March 5, 1896.

4.Zemlinsky does not specify which Mozart quintet Brahms was examining: most likely the C Major (K. 515) or G Minor (K. 516).

5.In a letter to Simrock, Brahms recommended Zemlinsky as “both a person and a talent.” See Johannes Brahms, Briefwechsel, rev. eds. (Berlin, 1912–22; repr. Tutzing, 1974), 4:212. The work that stimulated Brahms’s letter was the Clarinet Trio in D Minor, op. 3, which had received a third prize at a composition contest at the Wiener Tonkünstlerverein. Simrock published the work in 1897.

6.A reference to the “tönend bewegte Formen” (forms moved in sounding) that lay at the heart of the aesthetic position on music espoused by Eduard Hanslick in his Vom Musikalisch Schönen of 1854.