Sunday March 25, 1990, 5:00 PM,

Ottawa Civic Centre, Ottawa, Canada

CATHY PHILLIPS STEPPED from the narrow corridor of grey cement walls onto the sudden spread of whiteness. Nothing in her past had prepared her for this moment: almost nine thousand ecstatic fans stood cheering while a sea of turbulent pompoms, banners and flags urged her forward. And the roar. Never before had she or the others been greeted with such a welcoming roar. The ten-thousand-seat arena, the press booth in the rafters, the TV cameras transmitting the players’ images to a million and a half viewers, and even the electronic scoreboard echoed the crowd’s acknowledgement. At last—the first official women’s world championship.

Like most of the others on Team Canada, Phillips had grown up playing shinny alongside her brothers on the backyard rink. She had practised and dreamed hockey without having “somewhere to go,” as she would later put it in a speech. “When I was playing we set our own goals,” she recalled. “Now we have world championships…. [We] are playing for all the women who never had the opportunity…. They never had the chance because it wasn’t their time.”1 Today was their time, and the first female Team Canada was determined to seize it.

For the first time in their lives the women were not paying to play; instead they were provided with equipment, jackets, travel money and hotel rooms. Despite the female sport’s almost one-hundred-year history, these elite players received little or no financial support. Even the national selection camp held in January had cost each player a fee of three hundred dollars and a significant chunk of their vacation time from work—expenses their male counterparts were not asked to cover. But now was not the time to consider the obstacles. Now was the time to focus on the game of their lives.

Two posters hung on the dressing room wall. One had the words “Positive, Prepared and Proud” emblazoned across the top; inspiring quotations penned by teammates crowded the space below. The other poster displayed a hand-drawn pyramid of Canada’s opponents stacked one on top of the other. The names of Sweden, Japan, West Germany and Finland were no longer discernible, having been buried under the rising pile of red dots that had been stuck over each of these countries’ team after a Team Canada victory. Only Team USA, the final hurdle, remained visible at the top.

Including Canada, eight countries had come to play hockey in Ottawa. The cream of Europe included Finland, Norway, Sweden, Switzerland and West Germany. Japan represented Asia, after China had yielded to world pressure following the Tiananmen Square massacre and pulled out of the Asian Cup competition. So far, the results of this world championship were vivid proof of Canada’s proficiency on ice. Canada had outscored its opponents 50–1 in the four round-robin games. This gaping difference was a blunt reminder to the other countries, with the exception of Team USA, of just how far they lagged behind Canada in terms of both skill and numbers. Canada surpassed every country with 7,500 women registered with the Canadian Amateur Hockey Association (CAHA) and estimates as high as 15,000 female players in total. Most of its competitors, on the other hand, had selected their players from a pool of fewer than 400 players. Six hundred Swedish women played the game; fewer than 300 had taken to the ice in Finland and Norway each.

Phillips swept down the ice to the net. Her short tousled hair, playful grey eyes and wide-open smile belied the steely control she could command in front of the net. At twenty-nine, she was a goaltender with seventeen years’ experience and was considered the best in the world. Phillips was a standup goalie who had perfected “quiet feet.” For a whole season when she was sixteen, her father, a former goaltender himself, took shot after shot on her, repeating relentlessly, “You’re moving again … you’re moving again … you’re moving again ….” His incantation made her dizzy with frustration, but she continued to practise with him, smacking her pads with her stick and mumbling to herself, “Gotta calm down, gotta calm down.”2 The years of practice had paid off. Now during games, she waited at the top of the crease, always letting the shooter move first, refusing to commit. “Watch the goal-tender’s feet,” Phillips would say, “and if she moves before the shot is taken, she can be beaten.”3

Phillips also honed her game as a girl by studying the NHL goalies on television. She admired Tony Esposito most of all and once wrote him a letter she never mailed suggesting ways in which he could improve his goaltending. When she was eleven, she joined a boys’ team in her hometown of Burlington, Ontario, as no girls’ teams existed for her age group. She was turned away after the first game because of her sex. Two years later Phillips joined a girls’ team. Driving home after games with her mother and father, she would tap her father on the shoulder from the backseat and groan, “O.K., tell me. I can’t stand it.” Unlike many hockey fathers, Bob was reluctant to criticize his daughter. When he did let her know what had gone wrong in a game, he inevitably mentioned just a few

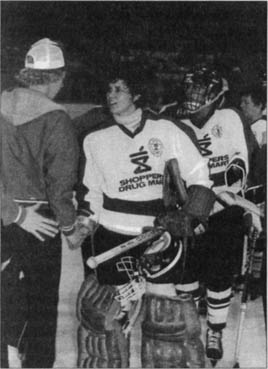

Cathy Phillips at the 1983 Canadian national championship.

ways she could improve. “He would never tell me what I did wrong if I didn’t ask,” says Phillips of her father. “It would always come from me. And then he’d always put a lot of positive in with the negative.”4

But here today, at the pinnacle of her career, all that Phillips had worked for was in jeopardy. For almost a year now, she had been plagued by double vision. At first she put it down to a pinched nerve, but by October 1989 her game was seriously off and she had to make a concentrated effort to compensate for what had turned into a real disability. Her peripheral vision was damaged on the left side. In order to see out of that side, she was forced to back into the net to focus on the oncoming puck with her centre vision. Using her left-side vision meant that she saw two pucks coming at her, not just the one. But it wasn’t only her game that was affected. Off the ice, exhaustion nagged her. When she lay down, dizzy spells or migraines set in. In January 1990, after what seemed like an endless series of visits to various doctors, Phillips learned she might have multiple sclerosis. She would have to undergo an MRI (magnetic resonance imagery) scan, a procedure similar to a CAT scan; the earliest appointment available was five months away. In the meantime, Phillips kept her illness a secret: deep down she knew this would be her final championship and she did not want the memory of it marred by special treatment, or worse, pity.

Phillips served as an emblem for the others because of both the talent and consistency she had demonstrated over a long career. She was one of the team’s veterans, one of the women who provided inspiration and reassurance for younger players. Another veteran was Shirley Cameron; at thirty-seven she was Team Canada’s oldest player. Cameron had been with the Edmonton Chimos, a dynasty in women’s hockey in Western Canada, through almost twenty years of trailblazing. Thirty-three-year-old team captain Sue Scherer came next in age. She was originally from New Hamburg, Ontario and, like the other Ontario players, was one of the few on the team who had grown up playing hockey with girls. Her godmother had played in the 1920s, and Scherer cherished her as a role model. By the age of ten, Scherer had pulled together a team on which she played the first of many years of organized female hockey. Although she stopped playing to coach for a few years in the mid-1980s, she returned to play in 1989, several years after bodychecking had been banned nationally (although not internationally) in female competition. The ban meant that the game was now safer for Scherer and many others who could not afford to take time off work due to injuries. In Scherer’s case, a hockey injury could also put her out of softball, another sport she played at the international level.

Thirty-one-year-old forward France St. Louis also counted as one of the older players. Despite her age, however, St. Louis represented a new breed of players who considered themselves elite athletes. The distinction between the veteran and the new players would rapidly become more pronounced. Women in the past had played for the sheer love of the game and the fun and sense of community that came from belonging to a team. The newer players, however, were less drawn by the social aspect of team play and more by the athletic heights it allowed them to reach. This distinction would emerge fully with future world championships and, eventually, the long-dreamed-of Olympics. The ground was shifting with this championship; the terrain was becoming steeper with competition.

St. Louis had come relatively late to women’s hockey. Like many of her teammates, the Québécoise had played shinny in a pair of figure skates with sawed-off picks as a young girl. Until 1978 girls were legally barred from joining boys’ teams—the only teams that existed in Quebec—and in her late teens by then, St. Louis had no interest in playing in a male league. She was an exceptionally focussed athlete and when she picked up the game again, at age nineteen, she did so with breathtaking alacrity. St. Louis was an intense player, a two-way forward who handled both ends of the ice with equal mastery. She also possessed an exceptional capacity to anticipate plays. Inevitably when she rounded up a season, her points total consisted of half assists and half goals—testimony to her ability to set up goal-scoring opportunities for both herself and her teammates.

Hockey was the second sport that St. Louis played internationally. Her dedication to lacrosse had led her to be named Quebec’s Athlete of the Year in 1986, and later Athlete of the Decade for the period 1980 to 1990. Nineteen eighty-nine had been her fourth and last year on the national lacrosse team; she had given up the sport to devote more time to hockey. In her home town of Brossard, Quebec, St. Louis played for the successful Quebec hockey team Repentigny. She had her first taste of international hockey competition in 1987 as the only Québécoise member of Team Canada in the unofficial women’s world hockey tournament.

At 5 ft. 8 in. (172 cm) and 140 lbs. (64 kg), St. Louis’ toned, resilient body reflected her dedication as an athlete. She stuck to a strict physical regime that involved going to bed by 9:00 PM and rising to train at 6:00 AM. St. Louis was a natural leader and acted as the link between the anglos and francophones on the team, often translating for members from Quebec who could not speak English. She possessed a stern sense of right and wrong and would admonish fellow players for dressing too casually when they went out together for the evening or for behaving in a manner that she considered unworthy of role models.

Today, however, St. Louis remained silent. During an earlier game against West Germany, a player had jabbed her accidentally below the chin with a stick. She suffered a bruised larynx and spent two days in the hospital struggling to breathe through a swollen throat. But St. Louis had waited too long to play at this calibre and was not going to let a minor injury keep her off the ice. After much coaxing she convinced the team doctor to allow her to join the team for the semifinal against Finland. She emerged from the game with one goal and two assists. Still, she was here today with a strict order from her doctor: don’t talk.

Stacy Wilson was the team’s only representative from Atlantic Canada. Born and raised in Salisbury, New Brunswick, a small village near Moncton, Wilson grew up playing on boys’ teams, always the only female in the league. When she turned fourteen, she moved up to bantam, a level at which the physical differences between girls and boys come into play. Wilson looked for a girls’ team in the area and when she learned that none existed, she had to give up the game. It was a painful sacrifice and for years she avoided hockey rinks. They were an acute reminder of what she had lost and what others—her former male teammates—continued to enjoy.

It was not until 1984 when Wilson was nineteen and attending Acadia University in Nova Scotia that she picked up the game again. Only three other women on her team had ever held a stick before. There were few teams to play against, but the Acadia team improved quickly and eventually represented the province in the national championships. When she returned to Moncton after graduating, Wilson played again in the national championship, this time as part of the New Brunswick team. With the help of her coach, she was selected for the Team Canada tryouts, pulled together the money for the camp, and flew to Mississauga, Ontario.

Although her integrity off ice shone through at the selection camp, her stickhandling and knowledge of the game did not: Wilson was wracked by nerves. She had played against many of the women from Ontario in national championships, but always as part of the underdog team and never in a gold-medal game. Atlantic Canada, like Manitoba, Saskatchewan and British Columbia, lagged far behind Quebec, Ontario and Alberta in terms of development of the women’s game. A handful of women’s teams existed in the whole Atlantic region, with only one Senior A team in New Brunswick. The camp, therefore, proved to be an intimidating experience for the Easterner. Coaching terminology that Wilson would later take for granted dumbfounded her. For instance, at the start of the camp the players were handed a sheet of questions about terms such as cycling, an offensive team tactic in which all three forwards maintain control of the puck while continually moving. The only cycling Wilson knew of was on a bike.

It was not until the scrimmage on the final evening of the selection camp that Wilson shed her hesitancy and surged forward in her trademark style of unstinting play. At the time, however, the effort seemed to go unnoticed. The next day, when one by one the players met with McMaster to hear whether they had made the team, Wilson was informed that she had had a good week but would not be joining the team in Ottawa. Wilson was crestfallen but understood. An hour later, however, she bumped into McMaster in the corridor of the hotel. He pulled her aside and told her that there was something in the way she played that had caused him to reconsider his decision. There would be another selection camp at which she would be reevaluated, he informed her. A few months later Wilson received a call. The selection had been completed without any more camps and she was now invited to join Team Canada.

Wilson may not have been the most agile stickhandler, but the moment this self-effacing woman stepped on the ice a player of rare tenacity took over. Coaches often said that Wilson brought new meaning to the term “workhorse.” Whatever system or strategy a coach laid down Wilson would stick to it unfalteringly. She was the player teammates could count on to block shots, hold up checks and take a hit so others could deliver the puck deep into the offensive zone. Wilson was a player who made opportunities for other players and was never one to retaliate when cross-checked or hooked.

These qualities that pulled the team together on ice acted as an emotional adhesive off ice. Wilson set a tone free of cheap putdowns of the opposition and when she took the floor in the dressing room, she spoke from the heart, subtly and naturally conjuring a feeling of team togetherness.

While Wilson with her quiet virtue had come to represent the heart of the team, teammate Judy Diduck was the stress-buster. The twenty-four-year-old Albertan exuded an endearing goofiness that made even the most anxious player laugh. Earlier today Diduck had flashed a surprise at her delighted teammates. Below her neck, just above her chest protector, “hung” a gold medal that teammate Laura Schuler had drawn with a felt pen. Although Diduck was not one for displays of cockiness, The Sports Network (TSN) had gotten wind of the temporary tattoo and coaxed her into revealing it on air before the game.

Behind Diduck’s quirky demeanour, though, stood a quiet leader. On ice her true nature was just as deceiving. Diduck was not a player opponents noticed right away since she rarely took big risks. During key games, however, she treated the competition to a cornucopia of little tricks using her skates and stick. If playing one-on-one in the corner, she would at times get beaten initially. Rather than panic and rush after the puck, Diduck would hold back. When the opportune moment arrived, she would almost imperceptibly tap the shooter’s elbow or lift her opponent’s stick, causing her to overshoot the puck. In front of the net, Diduck would often hover in the middle of two offensive players, refusing to commit to blocking one. When it was time for the opposition to shoot, however, she displayed an uncanny sense of which of the two players to tie up to prevent a goal.

This was the second world championship in one year for Diduck. In January she had represented Canada in the first ringette world championship. Hockey had been Diduck’s greatest love, however. She had tried out for a boys’ team at the age of ten but was not permitted to join. She contented herself by playing in net against her brother Gerald, who would go on to the NHL, and the other kids in her Sherwood Park neighbourhood, near Edmonton. Diduck would stand for hours between the two lumps of snow that served as goal posts, using only a baseball glove to stop the shots. She held back tears as pucks pummelled her unprotected shins, refusing to give the boys any excuse to exclude her from the game. The same stead-fastness she showed as a girl shone through today. Diduck had formally taken up the game only five years earlier and had moved from offence to defence less than a year ago. When she was asked to try out for the national hockey team, she held little hope of making it. Her detachment worked in her favour—she was as relaxed as ever and performed superbly.

While Diduck and Wilson helped sustain the team with their humour and integrity, forward Angela James injected it with raw, powerful energy. James, or simply AJ, was disputably the best—and toughest—female player in the world. She was also a player who had dedicated most of her twenty-six years to the game. The only mixed-race member of the team, James had grown up in a low-income housing area in east Toronto, the child of a white mother and black father. She knew through experience how the interest of a coach or teacher could change the course of a child’s life, so she now committed any spare time she had to helping other girls by coaching and refereeing female hockey games. She also knew the value of fighting to be part of something you love. As a girl, every night until the lights went out, she had played shinny with the neighbourhood boys in an outdoor arena beside the local school. She honed her resilience there, retaliating against the boys who whacked her over the head with their sticks by wheeling past them with the puck.

Solidly built with thick, powerful legs, AJ carried her body low to the ground. At 5 ft. 6 in. (145 cm) and 160 lbs. (72 kg) she was a forward who thrived on bodychecking and the rush it gave her both to hit and be hit. With her clever dekes and cannonball slapshot, she toyed with players, dominating every league she was part of and invariably breaking scoring records. This week had been “the ultimate”5 for AJ: she played or practised every day; her mother and older siblings sat in the stands cheering her on during games; and she luxuriated in her own hotel room and could eat all she wanted at the hotel buffet. She had also scored eleven of the fifty goals in the round-robin games, sent a Japanese player to the hospital with a broken leg, and was bruised from head to toe.

Three thousand kilometres west, across long stretches of ice-strewn prairies and lakes rigid with winter, sat eleven-year-old Hayley Wickenheiser in her home in Calgary. Her tiny frame buried under the jersey of her favourite team, the Edmonton Oilers, Hayley perched at the edge of the chestnut leather armchair in the basement rec room, excitedly waiting for the first women’s world championship on television.

Hayley had been playing since she was four. Born and raised in Shaunavon, Saskatchewan, Hayley spent every spare moment on the triangular span of ice that her father laid down each winter between their home and two others. There was not a feeling in the world she loved more than flying on her skates at night, the Saskatchewan wind biting into her face, her body on fire, flying, just flying.

Before she could even walk, she would trail around the town’s public skating rink on a sleigh behind her mother, Marilyn. When she was two and a half, she wailed when Marilyn bundled her up to go home: the hockey players were going on the ice and she wanted to watch.

Hayley signed up at age five for minor hockey and had since always played with boys. She was lucky: her father, Tom, coached her team, and not only spent hours teaching her to think hockey, but also shielded her from other parents’ resistance to her presence. Hayley’s dad put her on defence for five years to teach her patience because she rushed too much. She was fiercely aggressive, possessing a natural offensive instinct.

She also had the speed, finesse and toughness to make a remarkable forward. She would need these skills. When she moved up to centre at age ten, she invariably became the target of slashing and hitting. But she never once cried—instead, she took revenge by putting the puck into her opponents’ net. She scored the lions share of goals for her team and won the award for most valuable player (MVP) almost every year.

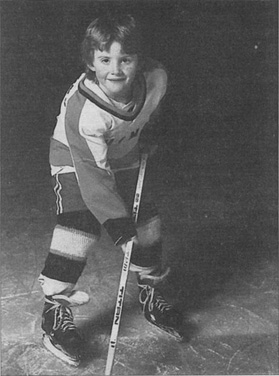

Hayley Wickenheiser, age five.

Until this week, when she had read about the first world hockey championship for women in the paper, her hockey dreams had been nothing more than fantasies. She used to imagine herself playing in the NHL, usually for the Edmonton Oilers. She knew that she would never make the big league—no women ever had at that point—and certainly it seemed unlikely that a woman who did not play in goal ever would. The physical differences between the sexes seemed just too great. But what else could she aspire to? There was no female hockey in the Olympics, no professional women’s leagues, and she had never before heard of an international tournament. But now, she thought with a flicker of hope, maybe there would be something else.

Back at the Ottawa Civic Centre the players streamed past the bench where head coach Dave McMaster and assistant coaches Rick Polutnik and Lucie Valois stood. McMaster paced anxiously, pursing his lips in nervous jerks. McMaster was a thirteen-year veteran with the University of Toronto Lady Blues and the winning coach of Team Canada in the 1987 world tournament. He was a soft-spoken man, renowned for his fairness. Earlier in the tournament he had told his players to keep the score down by passing the puck five times before shooting. Today, however, he gave no such advice.

During the two days of pre-tournament training, the women had soaked up the coach’s suggestions. They were hungry for any technical training and volleyed question after question at the coaches. Most of the players had encountered mediocre coaching at best and—victorious or not—were determined to leave the championship knowing the most they could about hockey. For Rick Polutnik, who was used to wrestling with the egos of male hockey players, coaching this team was an unexpected challenge. “With guys you have to kick the can and put on a show before they’ll react,” he explained. “Women aren’t like that, and certainly you wouldn’t get away with that. [They] want to know the plan, the long-term vision, the criterion to be successful. So as a coach, you have to plan your work more, because they want to know why and how. Guys won’t necessarily take that much information.”6

They would need the training to slip any pucks past enormous American goaltender Kelly Dyer. American coach Don MacLeod and assistant coach Karen Kay had selected a team of strapping players, attempting to make up for what they lacked in depth with brawn and aggression. MacLeod, commentator Howie Meeker pointed out, was notorious for his “one-second play” in which he sent all the bulky players on ice and had the forwards rush the opponents’ net on one side. When all else failed, intimidation and confusion often worked. Dyer, a daunting 5 ft. 11 in. (178 cm) and 172 lbs. (78 kg), was the team’s centrepiece. When she moved out of her net, she gave the impression of a wall sliding forward. Not only was she a threatening physical presence, but she generated an aura of cockiness that got under the skin of her opponents. Dyer wouldn’t hesitate to yell, “Shoot!” to put an approaching forward off guard or to shove a saved puck triumphantly in the face of a failed shooter.

If Dyer provided a formidable target for the Canadians, for her own relatively young team she was a confidence-booster. Cammi Granato was one of the younger players who appreciated Dyer’s presence. Granato led the American team’s offensive threat. Although not exceptionally quick, she possessed a long reach and a powerful, accurate shot. Granato sprang from a family that had produced four hockey-playing boys, the most famous of whom is her brother Tony, who played for the NHL’s Los Angeles Kings. When Granato chose to pursue hockey at the university level, she turned down scholarships and lucrative offers to continue with tennis, volleyball, basketball, handball

Kelly Dyer makes a save in the first women’s world championship.

and soccer—all sports at which she had excelled in high school. Instead, she opted for a hockey scholarship at Providence College.

Nineteen on the day of the gold medal game, Granato felt young and inexperienced—and also beat up after four full-contact games in one week. Now here was Canada, the real challenge of the championship, and like the rest of her teammates, Granato knew next to nothing about its players. A stadium of fans booing Team USA did not help matters. Still, she thought, better nine thousand boos than the usual silence.

From the announcer’s booth, Howie Meeker, veteran sportswriter, author and NHL commentator—one of the “voices” of hockey—surveyed the scene. Initially, Meeker had been less than enthusiastic about the assignment of covering women’s hockey. After the first few games of the tournament, however, his scepticism had been transformed into infectious delight.

The brand of hockey Team Canada played proved to be a startling reminder of just how far the men’s game had slipped away. This, Meeker announced, was how the game was meant to be played: strong skating, crisp passes, clean bodychecks, slapshots low and on the net, few offsides, and plays free of retaliatory stick work, boarding and fights.

Michael Landsberg from TSN chatted in the stands below with rookie colour commentator and former US college player, Canadian Donna-Lynn Rosa. Much of Landsberg’s initial commentary focussed on the uniforms. “They say the key to today is pink power,” Landsberg’s typically inane commentary went. “You see the pink uniforms. They wear the white with the pink numbers and pink socks. Pink is the colour of the day. Everybody’s wearing pink pompoms and waving them and wearing pink Canadian flags on their faces. Just that kind of excitement in this building.”

And, indeed, Team Canada’s jerseys were fuchsia pink and its pants, not the usual black, but silky white. Unconvinced that the tournament itself would attract media attention, the CAHA had selected pink as a way to generate controversy. The arena staff wore pink ties, and the pink flags, banners and pompoms waved by the fans were compliments of the CAHA. Even the Zamboni driver had motored about in a giant pink flamingo costume before the game, ten pink plastic flamingos jutting out from his vehicle. Many of the players resented the inherent sexism of the gimmick, but went along with it knowing that disagreeing openly could spell the end of their national team experience. They were all too aware of the “image problem” that surrounded women’s hockey: many parents denounced the game as too rough and masculine, and there were insinuations of lesbianism. Not one of these women hadn’t undergone some form of harassment when playing hockey. The players had laughed outright at the white pants, though, musing aloud that they hoped they wouldn’t get their period during the game or that their boxer shorts wouldn’t show through.

The teams completed their warm-ups and Canada pressed into a tight cluster around its net for one last round of energetic chanting before the face-off. Ken Dryden, former NHL goalie, author of The Game and vocal supporter of female hockey, stepped forward to centre ice to drop the official puck. Beside him stood his daughter Sarah, and Fran Rider, director of the Female Council for the CAHA and the driving force behind women’s hockey in Ontario.

At last the whistle blew. For the first fifteen minutes, Team USA overpowered the Canadians, who played tentatively, firing a few weak shots and struggling to clear the puck out of their own zone. The US took advantage of the situation, slipping two goals past Phillips. Cindy Curley popped in the first one at 2:25. Shawna Davidson poked in the second at 15:20. On the second goal, Phillips’s vision faltered. The puck came from the blue line on her left, hit the boards and bounced in front of the net, where Davidson slipped it in. Unable to see what was happening, Phillips assumed the puck had slid safely around the net.

Sue Scherer, left wing, and France St. Louis, centre, conferred at centre ice. “It’s time we do something about this,” Scherer urged.7 St. Louis nodded. Her eyes alone said she wanted the game badly. Thirty seconds later, St. Louis fired the Canadian engines with a quick wrist shot past Kelly Dyer. Another goal followed three minutes later when St. Louis passed to Judy Diduck, who swept down from her defensive position on a power play. Diduck flipped a shot high into the left corner after a rookie US defence allowed her to skate up to the doorstep, tying the game just before the end of the first period.

TSN used the intermission to read a telegram from Judy Diduck’s brother Gerald of the New York Islanders before it aired a profile of his sister. Rather than focussing on Judy, most of the interview consisted of questions about her brother’s role in her success. This typified the approach the media had long taken to the sport, inevitably seeking a link to the male game, rarely confident the female game could stand on its own. It was an angle female players found wearisome.

“I wish they’d [journalists] just take the game as a female hockey game and not compare it to [male] hockey or to boys,” summed up Diduck at the end of the interview. “Female hockey is getting a bad rap that way.”

The second period was marked by open-ice hits and end-to-end rushes. With the score tied at 2–2, the crowd was hungry for Canada to assert its authority. Team Canada kept the puck in the American zone, leaving little room for the Americans to manoeuvre. With just two minutes left in the period, defence Geraldine Heaney scored what would become known as “The Goal” in hockey circles. Heaney was a daring player from Weston, Ontario, ever poised to attempt the impossible. Her style fused humour and arrogance, a combination that on more than several occasions had paid off well. Today, Heaney broke from her own blue line and flew down centre ice, smelling the upcoming pass from France Montour. Taking the pass, Heaney faked US defender Lauren Apollo, slid the puck between her legs and whipped past her. Goalie Kelly Dyer sprang out of the goal-crease to cut Heaney off—but not quickly enough. Heaney whistled a wrist shot over Dyer’s shoulder into the net before swan diving over Dyer into the boards. The crowd broke into a frenzied blur of pink. From the media box, Howie Meeker squealed in delight, “She has the great goaltender playing the net like a beached whale!” The Canadians’ confidence soared: not only did they lead the game on the Scoreboard, but they now also led it in their minds.

Hayley raced to the phone at the second intermission to call her best friend, Danielle, in Shaunavon.

“Isn’t it incredible?”8 she exclaimed into the phone.

Already they knew each player by name. Susie Yuen was Hayley’s favourite because she was so fiery and was the shortest on the team, just like Hayley.

She hated the uniforms, though. Why had they chosen such a girlie colour? she wondered. Why wasn’t Team Canada wearing the national red and white? Even the long hair that had slid down from the backs of helmets bothered her. The fans, on the other hand, awed her. She had never seen such a crazed crowd except at NHL games. There just seemed to be tons and tons of them.

The two friends commiserated about the ugly uniforms and guffawed over the size of some of the Americans such as Kelly Dyer and Kelly O’Leary. Those players were so huge and chunky! They admired AJ for her speed and toughness. “Wow, these women are totally trying to kill each other,” Hayley laughed. “I totally love it!”9 They replayed Geraldine Heaney’s amazing goal and went over Diduck’s as well, which had seemed impossibly difficult to them.

What affected them the most, however, was what was said during and between the games. Hayley had listened closely to the interview with Judy Diduck on TSN. Having played on boys’ teams her whole life, Hayley had only known being compared with boys. The idea that there could be a separate, distinct female game seemed strange and novel to her. Howie Meeker’s comments about how hard the women played and how men could learn something from watching the women also astounded her. If Howie Meeker said it, she thought, then that really meant something.

With the score 3–2 going into the third period, Canada was in full swing. St. Louis opened up with a slapshot on Dyer; AJ decked an American forward. “Maybe people out there will believe us now that she can hit!” cackled Meeker. In a resplendent display of skills, Dawn McGuire on defence swooped, wove and swung her way between the net before clearing the defensive zone of the puck. Cathy Phillips performed a spectacular skate save on a slapshot by Cammi Granato, kicking off to the right and blocking the puck with the tip of her skate.

Halfway through the period, the youngest line of players on the Canadian team—forwards Vicky Sunohara, Susana Yuen and Laura Schuler, who had been affectionately dubbed the “Kiddie Connection” by the press10—showed its colours. Schuler and Sunohara brought the puck down the ice, Sunohara taking an unsuccessful shot on net. Yuen picked up the rebound and scored in a scramble in front of the net. It was a sweet victory for the petite player with lightning-fast feet and bruising resolve. Only 4 ft. 10 in. (145 cm) and 93 lbs. (42 kg), Yuen had been trounced mercilessly by the Americans throughout the game.

With less than six minutes to play, US Coach Don MacLeod put hard-hitting Kelley Owen on ice to inject some force into the team. The strategy backfired: Owen was sent to the penalty box just minutes after surging into play. For the remainder of the game, Canada played cautiously, protecting its lead. Thirty seconds before the game ended, St. Louis stole the puck from the American defence at their blue line and scored on the empty net. The goal clinched a come-from-behind 5–2 victory and dream game for the Canadians.

Team Canada rushed towards Cathy Phillips, forming a squirming nest of arms, helmets, gloves. For the first time in their lives the media swarmed around them. In the stands, a quartet of Canadian flags swayed in unison, pink pompoms fluttering on top. “Na-na na na, na-na na na, hey hey hey, goodbye …,” the crowd chanted.

Shirley Cameron joyously told a reporter, “We sort of felt that women’s hockey had been the best-kept secret in the country for one hundred years. Then all of a sudden they unveiled us in one weekend and the Canadian public came to the party.”11

“It’s like all you ever wished and never thought would happen was coming true,” exclaimed a beaming Sue Scherer.12 With these words, Scherer echoed the emotions of the eighty-year-old woman from Smith Falls, Ontario, who had made her way through the crowd earlier in the week to shake hands with Scherer. The woman had insisted her son drive her to the game in Ottawa. Clasping a worn photograph of her own hockey team from the early 1900s, she had told Scherer that her lifelong dream had come true that week: at last she had seen a world hockey championship for women.

It was just outside the dressing room that the most poignant reward took shape for the players. Champagne-soaked and giddy, the team stepped into a corridor packed with family, friends and dozens of young girls and boys clamouring for autographs and used sticks from their new-found heroes. Team Canada had succeeded at what many of its players most desired: it had shown a new generation of girls like Hayley Wickenheiser—who would devote the next years of her life to making this team—that they could claim a place in what was now the game of their lives, too.