INSPIRED BY THE SPIRITUAL and cultural traditions that permeate hockey in Quebec, Qué’becoise players tackle the game with a passion that has swept them to the forefront of women’s hockey in Canada. While the female game has a long history in Quebec, the powerful national position of the province’s female players is nothing short of extraordinary given the comparatively low number of women who play hockey here. Ontario bustles with more than ten thousand female players, some of whom have been on the ice since the age of six. Quebec, which has seven million inhabitants compared with Ontario’s ten million, has just slightly more than four thousand female hockey players, most of whom did not join the game until late in their teens. Yet Quebec has consistently supplied a plentiful crop of talented women to the Canadian national team. In addition its own teams have offered increasingly fierce competition to those of Alberta and Quebec’s archrival, Ontario.

The tradition of hockey runs deep in this province. The first covered rink in the world was raised in Quebec City in 1852, followed ten years later by the Victoria Skating Rink in Montreal from which North American hockey took its standard size. There the first world hockey championship for men was hosted in 1883. In this once overwhelmingly Roman Catholic province, hockey has taken on a quasi-religious meaning and, in more recent decades, nationalist overtones. Both these elements are apparent in the fact that the old Montreal Forum in which Quebec’s “national” team, the Montreal Canadiens, played for so many years was exaltingly referred to as le cathédral.

Female hockey, too, reflects Quebec’s history, mirroring its linguistic and regional divisions. At the turn of the century hockey was essentially a game of the upperclass and, in Quebec’s case, of English Canadians. Most women who played in an organized capacity did so as part of a university team. In the late 1800s McGill University women competed against women from Queen’s and the University of Toronto and then in 1900, as part of a Quebec women’s league, the first in Canada. Although some French-speaking women played in the anglophone leagues, the English dominated the circuit, as they did the province’s politics and economy. In the late 1960s when women’s hockey was in the throes of its first renaissance since the 1930s, hockey thrived in Montreal. The dominant east-end Aces Hockey League enjoyed sponsorship that covered the full cost of its equipment and expenses; the league included on its teams both francophone and anglophone women. Francophone teams, however, did not emerge as a force until the late 1960s when Quebec nationalism reached a feverish peak.

Québécoise players present an emotional and intense likeness of their region. Their style is a potent brew of small-town inclusion and defiant, individualistic flair. On ice the Québécoises are freewheelers; they make razor-sharp passes, take audacious shots and perform outlandish dekes. At national championships their team chants and songs before games are attacked with a gusto that could only come from those particularly intent on proving their worth—a sentiment that once again stems from the province’s uncertain position in Canada. Off ice they often resist outward signs of conformity such as wearing team jackets, which they view as a constraint on their personal expression.

Since the mid-1980s, France St. Louis has been the unyielding luminary of women’s hockey in Quebec. Born in 1958 in Laval, Quebec, St. Louis was the captain and one of the oldest members of Team Canada in both the 1992 and 1994 world championships. Her talent has won her many accolades: since 1984 St. Louis has been a member of nine senior national hockey championship teams, taking home six gold medals and winning MVP in 1988, 1990, 1991 and 1993. She has frequently acted as captain of the Quebec team at national championships and often has been the best female scorer in her senior league. In 1994 St. Louis inaugurated the École d’hockey France St. Louis, the first female hockey school in Quebec. She was also a remarkable lacrosse player. In 1985, just two months after first playing the game, St. Louis was selected as a member of the national lacrosse team and became its pivotal player in two world championships and five national ones. She has helped lead the way not only for Québécoise athletes; she also has set the standards for any female hockey player who dares to call herself an elite athlete.

St. Louis first took to the ice in a pair of figure skates in the well-to-do Montreal neighbourhood of Ahunstic, where she grew up. She hated figure-skating lessons and soon quit, preferring to spend her time playing shinny hockey at an outdoor rink with her brother, Bernard. Late one night when St. Louis was sixteen, she slipped out of the house with Bernard’s skates and sped around the deserted rink down the hill from her home. It was an intoxicating moment—the solid hockey skates hugging her ankles as she pursued the puck on the moonlit rink. Shortly after her parents bought France her own pair of hockey skates and Bernard joined her in the late-night outings.

When France joined her first organized female hockey team at nineteen, her parents, Lise and Guy, initially attended all the games. During games Guy paced anxiously behind the opposing team’s net. He was well-intentioned, but his presence caused France to lose her focus. After games he would chatter excitedly for hours, barraging France with tips and strategies. Eventually he understood the effect his presence had on his daughter and stopped coming to her games.

Since 1983 St. Louis has worked at the private Montreal high school, the Academic Michele Provost, first as a Physical Education teacher and later as the athletic director. Her teaching and coaching style is exacting. “Play like you practise,” she has often advised the girls’ basketball team. “If you don’t do anything during practise, you won’t accomplish anything during the games.”1 Rather than alienating her students, her tough approach has won her admirers. After the 1994 world championship, the school’s principal, Michele Provost, presented St. Louis with a $100 gold coin from the 1976 Olympics in front of a gym full of cheering students. Provost has also granted St. Louis the time off she requires to fulfill her hockey commitments. Although such support may seem standard for a world-class athlete, most Team Canada members are docked pay from their jobs while away at world championships. Others have risked losing their jobs entirely by taking time off.

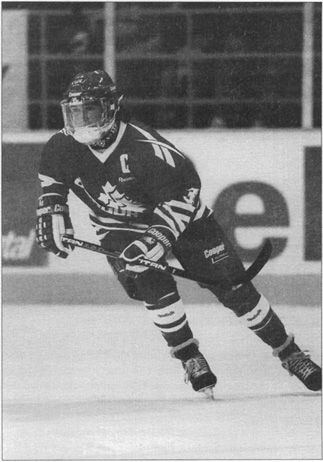

Unlike many of her provincial teammates, St. Louis is not a flashy player. At 5 ft. 8 in. (172 cm) and 140 lbs. (64 kg), her tall, svelte body travels the ice with studied rigour. She reads the play well, capitalizing on opportunity with her decisive passing. Her precision on ice is merely an extension of her office persona. St. Louis is almost fanatical about promptness,

France St. Louis, captain of Team Canada, 1994.

fastidious about her equipment, and can be regimented even when on holidays, rising at the crack of dawn to train. “She’s kind of nutso sometimes,” sums up her close friend and former Ferland–Quatre Glaces teammate, Therese Brisson, with a laugh. Brisson recalls the time at a tournament in Trois-Rivieres when St. Louis’ skates were returned late from the sharpener’s. St. Louis had asked Brisson to pick them up from the shop and bring them to the tournament. When Brisson was delayed due to traffic, St. Louis panicked; pacing frantically up and down the aisles, she asked everyone in earshot if he or she had an extra pair of skates. “By the time I got there,” recalls Brisson, “the whole arena knew France St. Louis needed a pair of size seven skates. I mean her nervous energy had the whole place on edge.”2 Teammates have often had fun with this side of St. Louis’ character, hiding her skates just to watch her go into a frenzy. She responds good-naturedly to the teasing. Despite her finicky side, she is even-tempered and displays an ironic sense of humour refreshingly free of putdowns or barbs. She is also a master at galvanizing her teammates with enthusiasm. “France makes you want to buy into it,” says Brisson. “She makes you feel like you can be like her.”3

All of St. Louis’ decisions—from selecting an office with a shower so she can go directly from the gym to work to carefully monitoring her diet, sleep and fitness—are centred on her goals as a hockey player. She is never without a goal, forever measuring her objectives against tangible contributions she can make to her team. But as with many elite athletes, her self-worth as a person often depends on her athletic performance. The perfectionism, teammates say, also reflects a fear of letting go of her drive—a drive that at times has worked against her. In the 1987 national championship, St. Louis experienced the perils of overtraining, pushing her body so hard that it lost its much depended-on resilience. She was plagued by exhaustion. On ice she found she couldn’t catch her breath and office she lacked her usual enthusiasm and interest in others. “It was basically a lack of maturity,” explains St. Louis in retrospect. “I just didn’t listen to my body.”4 The experience forced her to reconsider her approach to training and gave her the necessary maturity to grow as an athlete.

Now after a stressful week St. Louis goes home and relaxes in front of the television rather than pushing herself to train. She spends an average of only eight hours a week training, including two hours every other week skating. (It is not by choice that she spends so few hours on ice, but rather because of the prohibitive cost of renting ice time and the lack of ice available for senior female teams.) The perspective St. Louis now possesses does not detract from her focus. Indeed, with the Olympics hovering in the near distance, St. Louis has fused her dedication and maturity to redefine just what is possible for her as a player in her late thirties. For St. Louis the race to Nagano, Japan, the 1998 Olympic site, is not just a race against younger players, but a race against the clock. Prior to the national team tryout camp in the fall of 1995, coach Shannon Miller doubted St. Louis could triumph over such odds. “She has the talent and leadership,” Miller had contended, “but it’s a matter of her age slowing her down. It just does. That’s life.”5 To Miller’s delight St. Louis proved her wrong. The player performed remarkably well at the camp and consequently was ranked as one of the top ten players in the country. “What can I say?” says Miller, beaming. “She’s an amazingly dedicated athlete.”6

Since the early 1980s St. Louis has been the mainstay of the senior club team Ferland–Quatre Glaces (formerly Repentigny) of Brossard. The twenty-four team Repentigny Regional Female Hockey League (League Régionale du hockey au feminin) just north of Montreal boasts the strongest competition in the province. For a twenty-year period beginning in the mid-1960s, the Montreal Titans—composed of both French- and English-speaking women—dominated the league, representing Quebec in the early years of national championships. Since the mid-1980s, however, Ferland–Quatre Glaces and its rival, Jofa-Titan (formerly Sherbrooke), have formed the heart of the league.

Ferland–Quatre Glaces is distinguished by a handful of star players and a sentinel of “plumbers,” those less skilled players who work hard following a system laid out by the coach. The team trains under the inspired coaching of Daniele Sauvageau, a member of the national coaching pool who works nights as a narcotics detective. National talents such as goalie Denise Caron, and defence Therese Brisson, one of the first anglophones to join a club team, have also played for Quatre Glaces. (Brisson now lives in New Brunswick and plays on its only Senior A team.)

Jofa-Titan, on the other hand, is rife with exceptional talents. It has included national team members Nathalie Picard, Nancy Drolet, Diane Michaud, Danielle Goyette, France Montour, goalie Marie-Claude Roy and, for a brief period, even Manon Rhéaume. For many years the team was held together by captain Nathalie Picard, known affectionately by other players as “Picou.” On defence Picard had a clear grasp of how games unfold. She acted as the team’s backbone, curbing its tendency towards individual play through her under-stated leadership. Picard’s influence, combined with the talent of the players, carried the team from playing in the B league in the early 1980s to stealing the gold at the 1988 national championship. As team captain of the first official Team Quebec in 1993, Picard introduced the team’s motto, Fière d’être québécoise et hâte de gagner (Proud of Being Québécoise and Set On Winning.) When Picard retired from hockey in 1994, Nancy Drolet of Drummondville took on the role of team leader, becoming its manager. Still in her early twenties, this young player has displayed remarkable skating skills on ice and an

Québécoise members of Team Canada celebrate another gold medal at the 1994 world championship. From left to right: Nancy Drolet, Therese Brisson, France St. Louis, Laura Leslie, Danielle Goyette, Nathalie Picard.

office knack for organizing team finances and attracting sponsors. She was instrumental in leading the Quebec junior team to a bronze medal in the 1991 Canada Winter Games and awed fans at the 1992 world championship with her hat trick. In 1993 Drolet was named Junior Athlete of the Year by the Sports Federation of Canada and the “next great women’s player” by Inside Hockey magazine.

Drolet began playing female hockey at age fourteen after nine years on boys’ teams. She is naturally gifted and with the frequent practices and superior coaching of the boys’ league she was able to hone her liquid acceleration and brazen shots on net. Drolet and teammate Danielle Goyette, the most effortless and creative scorer in Canada, form a lethal pair. As members of Jofa-Titan, the two carefully observed one another on different lines for four years. They finally played on the same line in the 1992 world championship. When they played together, instinct took over; Drolet and Goyette wove throughout the games as if attached by an invisible thread, uncannily anticipating one another’s moves.

The intuitive style of Drolet and Goyette aptly characterizes Jofa-Titan. The team does not practise, relying instead on the natural talent of its players and its experience together. Jofa-Titan clearly outweighs its chief rival, Ferland–Quatre Glaces, in terms of skill. But when key players from the team retire or move on, it has to struggle on ice to maintain its advantage.

By 1995 twelve senior leagues consisting of fifty teams were registered with the Quebec Ice Hockey Federation (QIHF). This almost represented a doubling in the number of players since 1991. These leagues do not include the teams of Concordia University, University of Quebec at Trois-Rivieres, St. Laurent College or McGill University. Concordia female hockey has enjoyed varsity status (which means it is financially supported by the university) since 1975 and equitable funding since 1985. The money channelled into the program has translated directly into better coaching and higher calibre hockey. This is because the program attracts players with higher goals, who in turn demand higher standards. The university teams have proven to be particularly important in developing players between the ages of sixteen and twenty-five, while the club teams for the most part offer opportunity to women who are twenty years old and over.

While the Quebec women’s senior teams have produced a superb yield of national athletes, until 1992 the system was plagued with troubles. Each year teams such as Quatre Glaces and Sherbrooke set out with the primary goal of winning the provincial championship and the right to represent Quebec at the national championship. “Stacking,” the best players flocking to these few teams, became regular practice. This resulted in the near ruin of the competitive network of the A level (now called AA). One team after another dropped out after consistently losing games to the dominant two or three teams by as many as twenty goals. The problem was by no means unique to Quebec: stacking had hindered senior league development in Ontario, Alberta and British Columbia, as well. But to further detract from the stability of the Quebec league, the leading teams played with skeletal rosters of twelve or thirteen players in regular season. The better players understandably wanted more ice time and saw the limited number of players as a way of spending less time on the bench during games and more time in play. At the 1990 national championship hosted by Quebec, the province featured the lowest number of registered players in Canada. To mask the reality, the team representing Quebec placed “ghost” players on the list: coaches, managers and retired players—one of whom was born in 1936 and was in fact the mother of a player. Although the Quebec team won that year, the skeletal rosters worked to its disadvantage at the national championships since it competed against full teams of nineteen highly skilled players.

The selection process for the national team also proved to be a muddled affair across the country and Quebec was no exception. Provinces were not notified by the CAHA of the 1990 championship until mid-October 1989. A quota system of recommending players to the national team tryouts was set up and Quebec was asked to list ten players by November. Given the short notice, a committee headed by Quebec female council representative Lucie Valois decided to target the four teams officially registered in the Senior A league. These players were sent forms that asked them if they were interested in attending national team tryouts. According to Valois two of the senior teams boycotted the process as a way to force the CAHA to change it. Instead, says Valois, they wanted the same selection process that had been used for the unofficial 1987 world championship in which the winning team from the national championships had represented the country. In the end six players reversed their decisions, four of whom were eventually chosen for Team Canada, Valois reports. “I am still bitter about that episode,” she says, “where Senior A players were so misled by their coaches and some influential players [into boycotting the event].”7 Players, however, tell a different story, saying they were more confused than anything by the process and that the significance of the event was never properly explained to them. When the Québécoises who played in the first world championship returned, those who had opted out also felt bitterly led astray.

Valois, a medical doctor and headstrong member of the CAHA female council from 1985 to 1993, was irked by the flaws in the senior leagues. In 1993 Valois worked with the QIHF’s Excellence Commission, where she developed a scheme to both remedy the ills of the senior teams and foster growth within minor hockey, where female numbers had just begun to rise. She designed a program whose main thrust was to develop a provincial team. Valois modelled the program on the female under-18 Program of Excellence that had been set in motion for the first Canada Winter Games in 1991 and had continued for the 1993 under-18 national championship. She presented the elite program to the QIHF, which in turned requested a grant from the federal government to launch it. It was approved, most likely because it complied with Sport Canada’s point system, which favours the funding of sports benefitting both elite and largely underrepresented female athletes. In 1993–1994 Quebec competed in the national championship with its first all-star team, making it the only province to be represented by its best players rather than the winning team of the provincial championship.

Outside of Quebec, the program was not widely appreciated. Alberta and Ontario especially resented the advantage an all-star team gave to Quebec. Ontario argued that such a system denied less talented members on the winning provincial teams a chance to play in national competition. Within the province, however, the program has been an unequivocal success. Not only has it solved the stacking problem by offering all the better club players a chance to play on the provincial team, it has also cleared up the selection process for the national team, guaranteed a full roster of provincial team players and provided a tangible goal for younger female players in the province.

Team Quebec’s budget totalled $25,000 in 1995–96, a considerable sum for a provincial elite female program. This figure is particularly striking given that other senior provincial championship teams scramble to raise the money simply to attend the national championship. Up to $12,000 is supplied by the provincial hockey federation, several thousand by the CHA and the rest is made up through player fees and fundraising.8 Despite the relatively generous funding, the program is run entirely by a volunteer staff consisting of one director of operations, three coaches, one physiotherapist and one equipment manager. When the director of operations, France Lajoie, has inquired about receiving an honorarium for the hours of work she and others devote each week to the program, federation managers have said, “That’s how it works; there’s nothing we can do about it.”9

Lajoie, formerly the president of the Repentigny senior women’s league, took over as the voluntary director of operations of the program in 1994 and added a pool of three advanced-level coaches to work with the team. The pool includes Daniele Sauvageau and Concordia University coach Julie Healy, both part of the CHA coaching pool. Healy was head coach of the under-18 provincial team in 1993 and of Team Quebec in 1995. The addition of coaches to the program reflects Quebec’s commitment to developing a corps of expert female hockey coaches, a priority that is absent in the rest of Canada. The percentage of women coaching female teams is high in Quebec because the hockey federation has made coaching certification mandatory for the intermediate and elite level teams. Since 1986 the federation has organized coaching courses exclusively for women, many of whom have felt daunted by the traditionally male terrain. The courses paid off and by 1995 women coached all AA teams, six of the seven senior club teams and the majority of the sixteen BB teams. The varsity teams, which represent the best-paid positions—or, in the case of women’s hockey, the only paid ones—are still largely coached by men. So, too, are teams at the minor level, where the concern has been not so much to develop female coaches, but simply to provide girls with decent coaches.

While the provincial team program has undoubtedly raised the skills and aspirations of elite players in Quebec, until recently the province has failed to offer much to the majority of young female players. Girls have been playing in the minor hockey leagues in Quebec since the early 1980s. They began to play following the 1978 court decision in the Québec (Commission des droits personne) c. Fédération québécoise de hockey sur glace Inc. case that forced the federation to allow female players into its leagues. By 1995, seventeen years later, only 990 girls played on female minor teams and 1,012 on boys’ teams, making up 5 percent of the minor players in the QIHF. While the Ontario Women’s Hockey Association has been providing opportunities for girls since 1975, the Quebec federation only began to actively promote female participation in 1990. Ontario’s provincial Winter Games have included girls since 1985. Quebec’s Winter Games didn’t embrace female teams until 1996.

Marc Beaudin, manager of female hockey at the QIHF, insists that girls’ hockey is now a priority. According to Beaudin, in addition to the elite program between $20,000 and $30,000 is spent annually on female hockey, a sum that is spread out over salaries, administrative costs and a number of programs. Like so many of the provincial associations female program directors, Beaudin becomes defensive when asked for the portion of the overall budget of minor hockey that goes to girls. Indeed, many associations refuse to release figures pertaining to female hockey or else claim that such figures are impossible to calculate given that some girls participate in their mainly male programs.

As part of its strategy to offer more opportunity to girls who wish to play hockey, however, Beaudin points to the Quebec federation, which held its first minor hockey leadership seminar for regional representatives in 1994. Representatives from all fifteen hockey zones in the province attended to discuss ways to promote female participation. Foremost among the suggestions was the need to publicize the sport to girls, particularly given the high level of resistance to female players in communities that are strapped for ice time. This is no small point, as it is the local associations that decide whether or not they will accept girls’ teams. In some cases, however, when the local towns refuse to form girls’ teams, female organizers have turned to one of the fifteen zone (or regional) associations to launch the teams. This is because the zone associations permit their players to come from larger geographical areas. For new, struggling female teams, the chance to draw players from a larger pool often determines their ability to survive. To further increase the competitive opportunities for girls, in 1995–1996 the federation launched a new provincial championship for girls under-16 called the Chrysler Cup at which an all-star team from each of the fifteen zones competes.

Senior players now await a similar championship. Although senior tournaments are held about once a month, with the formation of the Quebec all-star team program, club competition among leagues has fizzled since there is no longer a provincial championship where teams vie to represent Quebec at the national championship. While the all-star programs provide the better players with proper training, the system has also brought out an individual approach to the game. Players are now less concerned about playing as a team and instead focus more on accomplishing their personal goals. As the stakes are raised in the province, a significant shift in values—from collective to individual—is emerging. Some have suggested that to restore the once important team incentive, Quebec should launch a new senior championship in which all levels of teams compete.

Quebec female hockey may have only recently begun to receive the funding and tournaments it deserves, but it is strides ahead of its fledgling Eastern neighbours. This is not to say that Atlantic Canadian women’s hockey is a new phenomenon. It possesses a proud and spirited history that extends from Newfoundland’s undefeated Bay Roberts Roverines and PEI’s Crystal Sisters of the 1930s to the enterprising PEI Spudettes of the 1970s. Nonetheless, it has been an ongoing struggle for female players in the region to make even a dent in national competition. In each of the four Atlantic provinces—New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland—the survival of the female game has fallen on the shoulders of solitary individuals, who, without support from local hockey associations or parents, have propelled the game forward. The broader lack of interest in promoting girls in the sport has created a fragile system, one that has crumbled when lone organizers leave in exhaustion and frustration. This situation is exacerbated by the geography of the provinces: major centres are few and far between and travel between provinces often involves a costly flight or ferry crossing. These are expenses many of the depressed communities cannot afford. Consequently, the sort of tournaments and jamborees that have thrived in the West have been small and sporadic in the Atlantic provinces. Even the Atlantic Shield (formerly the Eastern Shield), a tournament for junior and senior teams, has been held only once since its rebirth in 1990.

Despite these obstacles, a tradition of female hockey has survived in the East, and it is due to the hard work of a handful of women and men. By far the most well-known and admired leader is New Brunswick’s Stacy Wilson, who has been a member of Team Canada since the first world championship in 1990 and is also captain of the New Brunswick provincial team. The similarities between Quebec’s France St. Louis and Stacy Wilson are striking. Like St. Louis, Wilson teaches Physical Education and has used her background to painstakingly prepare herself for international competition. She has been instrumental in launching the first female hockey school in the region and has demonstrated a deep sense of regional loyalty as assistant coach in the Canada Winter Games and through her involvement in female jamborees and clinics. But while St. Louis is surrounded by players of similar talent and drive in Quebec, until very recently Wilson has been peerless in Atlantic women’s hockey. Rather than moving to another province, where she would undoubtedly face more and stronger competition, Wilson has remained in the region. There, almost single-handedly, she has raised the calibre of female hockey.

Wilson would deny her pivotal role in female hockey in the Atlantic provinces. She is a shy, unassuming woman with a slight build; her blue eyes, set against coal-black eyebrows, startle with their transparency. Teased by her friends and teammates for refusing to drink or swear—her harshest expletive is “Geepers creepers!”—Wilson is, however, anything but moralistic. At parties she is invariably the last one to leave, often overcoming her timidity to pick up her guitar and play. Wilson, nonetheless, remains firmly reticent with the press: attention leaves her uneasy. Often after a story appears that portrays her as a star, she will grimace to teammates and ask, “Do you think that article was O.K.?”10

Her reserve, just as much as her commitment to building confidence in female hockey players, has won her a coveted place in the hearts of Maritimers. Born in Moncton in 1965, Stacy Wilson grew up in the tiny nearby village of Salisbury, the youngest in a family of three children. Although she is an allround athlete—an Atlantic champion in badminton and an accomplished golfer and swimmer—hockey won out over these other sports. The sense of freedom skating brought her, the cleansing mental effect of the cool rink air, even a feeling of patriotism at playing Canada’s national sport seized Wilson’s imagination as a child.

Much of her love of the game also sprang from her belief in team work, a value instilled in her by her parents and a community that celebrated her struggles and victories as its own. Wilson’s mother, Betty, accompanied her to every game when Stacy played in a minor boys’ league. Betty, who like her daughter is uncomfortable with the braggadocio that goes with many competitive sports, sat apart from the other hockey parents during games to avoid their hostile bellows. If she overheard someone deriding Stacy, she would diplomatically defend her. Stacy’s community was behind her, too. When Wilson returned from the 1990 world championship—the only Team Canada representative from the Atlantic provinces—Salisbury held a reception for her in its community hall and declared her Citizen of the Day.

Wilson became a force in hockey in the Maritimes in 1984 during her second year at Acadia University in Wolfville, Nova Scotia, when she helped form a team. The next year Wilson led this group of inexperienced players to a provincial victory against the seasoned Dalhousie University team, which had defeated them the year before 18–0. She returned to the Moncton area to teach in 1987 and joined the Jaguar women’s hockey team, now known as the Maritimes Sports Blades. In the 1980s the team played in a small league, usually competing against the University of New Brunswick in the provincial finals. In the early 1990s the Sports Blades became the only A team in the province and has since acted as the provincial team. It draws players from all around New Brunswick. Most commute hours each weekend to Moncton to be part of the team. Because the Sports Blades team is literally in a league of its own, it lacks a fixed schedule, organizing ad hoc games against men’s teams from week to week. Practices are held in a small arena outside Moncton late on Saturday nights and on Sunday mornings.

For years the Sports Blades wallowed in what it came to call “the toilet bowl” of fifth or sixth place nationally. At the 1994 national championship, after a particularly bitter defeat against Alberta in a preliminary game, Wilson penned her frustration in a journal:

Feeling a game slip away is a horrible, sickening feeling. I have lost … games before, but this one really hurt, I guess because I believed in our team. I’m proud of the team, but can’t quite express it in the dressing room, as everyone silently takes off the gear more slowly than usual, like they are still trying to slow down the clock. We know we are in the “toilet bowl” again. We have been in this game so many times and so close to breaking through that I think we have earned the right to call it that. We own it. It’s the first time I’ve cried after losing at Nationals.11

Determined to escape the toilet bowl, Wilson conducted a closed-door visualization session with her teammates before the final game at the 1995 national championship. As the players drew together in the dressing room, Wilson quietly handed each member a small piece of gold, asking her to tape it to her body or slip it into her skate. The day before the gold bits had formed an individual achievement medal, which Wilson had been awarded after an earlier game. At her request the team’s equipment manager had spent three hours slicing the medal with a hacksaw into nineteen pieces so that Wilson could literally share her medal with her teammates. Although the team lost to Quebec, New Brunswick took home its first silver medal in the national championship. It was a fairy-tale victory for Wilson.

While Wilson’s presence on the New Brunswick team has transformed its members into contenders for the national championships, Team Canada has performed a similar alchemy on Wilson. Before she was selected for the national team in 1990, Wilson did not regard herself as a serious athlete. This only changed just before the 1992 training camp. During workouts on a Nautilus machine at the local gym, Wilson stared at a poster someone had hung on the wall. It displayed a quotation from the German poet Goethe. “Until one is committed, there is hesitancy, the chance to draw back, always ineffectiveness, concerning all acts of initiative (and creativity),” its first lines read. “Whatever you can do or dream you can do, begin it. Boldness has genius, power and magic in it. Begin it now,” it ended. Contemplating these words, Wilson realized she must now give absolutely everything over to the game of hockey. Either that or stop playing altogether.

Since her transformation in 1992, Wilson has not been without doubts or fears. Attending national tryouts for Team Canada is always intimidating, particularly as more younger players, who have had better opportunities, are invited to attend. Although she stands out on ice with her stalwart forechecking and willingness to fill any necessary role, Wilson

Stacy Wilson (back left corner) with players at her hockey camp.

worries about her lack of ice time and insufficient exposure to tougher competition. She must also deal with the stress of juggling work with hockey: when she plays for Team Canada, Wilson forfeits her teaching salary and also must pay the substitute who replaces her. Furthermore, when Wilson played at the 1994 Lake Placid world championship at the age of twenty-nine, the media dogged her with questions about her age, implying her retirement was imminent.

While most of Wilson’s energy goes into training as a player, she has also coached girls since 1990. Along with Michelle Belanger, who has been the New Brunswick representative for the CHA Female Council since 1992, and teammate Joanne Vautour, Wilson founded a hockey camp for girls in 1995. The school means a great deal to Wilson, who is resolute about giving girls the opportunities she never had as the only girl on a boy’s team. Wilson’s presence has also meant much to young hockey players in the region. It meant so much to one girl that she burst into tears of joy when she first sighted Wilson at the camp.

Currently in this province of 750,000, almost 300 girls participate in minor hockey. In 1995 the New Brunswick Interscholastic Athletic Association formed a league of high school teams, which Michelle Belanger registered with the provincial hockey association. This gave a much-needed boost to girls’ minor hockey. By 1996 fifteen female high school teams were competing in the province. Three all-girls’ teams have also registered since 1995. Having succeeded in increasing the numbers from year to year, Belanger’s current goal is to ensure female representation in the province’s eight hockey zones. Already six committed representatives have begun to promote the game in their zones.

With a population of 132,000, Prince Edward Island presents an impressive example of female inclusion in hockey within Atlantic Canada. In 1991, the year of the first Canada Winter Games held in PEI, only four minor girls’ teams played. By 1995 more than thirty-five female teams competed, twenty-five of which were minor; the rest were senior or recreational teams. Fifteen percent of the minor hockey players in the province are female, 90 percent of whom belong to all-female teams.

Several elements have combined to make PEI the female minor hockey leader in the region. First, the island boasts the highest number of indoor rinks per capita in the world at twenty-five and thus, with the exception of its major centre, Charlottetown, ice time has been readily available to girls. Second, the number of boys playing has dropped in the last decade, and hockey associations have eyed girls’ participation as a way to revitalize the sport. Third, and most important, PEI has been blessed with one of the most committed promoters of female hockey in Canada: Susan Dalziel. Dalziel’s love of hockey blossomed in 1973 when she played on her first organized team, the Kensington Spudettes. The team sprang from a long tradition of female hockey on the island, which took root with the famed Crystal Sisters and Charlottetown Abegweit Sisters (the Micmac name for PEI, meaning “cradle on the waves”) at the turn of the century. Member Kay McQuaid played nets for the Spudettes from 1968 until 1984, when she joined a rival team, the Island Whitecaps, and ended the Spudettes’ winning streak in the East. McQuaid’s girlhood practice sessions embodied the whimsical essence of PEI life: she took shots from her brother behind her family’s barn on a dark, layered rink formed from the moisture drainage of a manure pile; she used potato bags stuffed with straw and fastened to her legs with old binder twine to protect her shins. In the Spudette’s early years, members played without helmets, and more than once a bouffant wig worn by a player would fly off—bobby pins and all—following a solid bodycheck.

The Spudettes travelled to tournaments in the East and Ontario in an old Ford camper van, which had to be jump-started after the ferry crossings. McQuaid’s mother followed the team religiously—literally. She cheered players on with an old cow bell, intermittently fingering her rosary beads and whispering Hail Marys to protect them from injury. In 1976 the Spudettes won the B championship at the Dominion

Spudettes, 1976. Goalie Kay McQuaid sits second from left in front row. Susan Dalziel, one of the sports’ most committed proponents, sits on the far left, second row.

Ladies Hockey Tournament in Brampton and placed second the next year in the A championship. The highlight of the team’s career came in 1976 at the same tournament, then the largest women’s hockey tournament in the world. The team was chosen from among seventy Canadian and American teams as the recipient of the Roy Morris Sportsmanship Award, and the choice was unanimous. After losing the final game of the tournament, the Spudettes took to the dressing room, stood along the benches and burst into song. “We’re PE-Island born and we’re PE-Island bred,” they belted, “and when we die, we’ll be PE-Island dead!”12 “The island is small and people feel closer than they do other places,” reflects McQuaid. “A lot of people didn’t have a lot when they started out and when you get something it means a whole lot to you.”13 The coach from the opposing team, the Mississauga Indians, remarked wryly about the singing, “What do they do when they win?”14 By 1980 travel had become too expensive for the team and with no minor hockey teams from which to draw talent, PEI stopped competing in the Dominion Tournament. When the national championship was launched in 1982, PEI managed to send a team until 1989, when lack of money again forced the province to forego the event until 1995.

Dalziel, a modest schoolteacher, first became involved in organizing female hockey in 1977 when she came across an announcement in the local newspaper for a Canadian Amateur Hockey Association (CAHA) seminar about the future of female hockey. Dalziel attended the seminar, an early version of the Female Council that was formed in 1982, and has since been a driving force of the sport at most of the Female Council’s yearly meetings. Also in 1977 Dalziel became the PEI girls’ coordinator and then, in 1980, the director of Female Hockey in the province.

The late 1970s and early 1980s were prosperous years for female hockey and Dalziel worked intensively on the sport’s behalf, staging coaching clinics for women, putting out a newsletter and encouraging communities to include girls in their leagues. Despite her efforts the number of female players dropped drastically by the mid-1980s, as the violence in both the amateur and professional game turned many parents off hockey. For almost a decade, Dalziel laboured single-handedly to keep what was left of the female sport alive. She began to wonder whether she had wasted years of her life on a pipe dream and was on the verge of abandoning the game when, in 1988, the provincial hockey association asked her to coordinate female hockey for the 1991 Canada Winter Games. The Games were to be held in PEI in what would be the inaugural year for female hockey. At last Dalziel was able to put her experience and wisdom to use to promote a game whose reputation had been restored. Parents soon came aboard to help her, although financial support from the local association is still not forthcoming. “I used to find with the hockey association in general, the funding would go to different male programs,” says Dalziel. “I didn’t ask and they didn’t volunteer. There’s not as big a discrepancy now as there used to be, but that’s because money is dropping all round.”15 Nonetheless, PEI’s minor female hockey leagues have become a beacon for its neighbours, a luminous example of what can be achieved with the proper conditions and the work of a tenacious leader.

In Nova Scotia Lynn Hacket, the first representative of female hockey in the province, attended her inaugural CAHA meeting in 1983. At the time Nova Scotia sustained only a three-team senior league. “It felt like I was in a foreign country—that the national border stopped at Quebec,” Hacket recalls of the CHA Female Council. “I couldn’t fathom that Ontario had three hundred teams. I could only laugh. I was too embarrassed to even open my mouth about our little league. I had absolutely no idea that so much was going on.”16

From 1973 to 1978 the densely populated area of Halifax-Dartmouth had supported a league of six senior teams. In 1976 the demise of the local league was set in motion when a competitive team, the Fairview Acettes, was formed to challenge the Halifax university teams of Dalhousie and St. Mary’s. The Acettes stripped the other club teams of their best players and quickly overwhelmed the rest of the teams in the league. But the league’s coup de grace came in 1978 when the City of Halifax suddenly refused to subsidize ice time for the league, claiming it had just discovered that girls over the age of eighteen were playing, which was against the city rules for boys’ hockey. League members were outraged and claimed that the age restriction rule was simply an excuse to get them off the ice: what city officials really wanted was to free up more ice time for the swelling boys’ league.

From the early 1980s to 1990, the three university teams from Acadia, Dalhousie and St. Mary’s carried women’s hockey forward in Nova Scotia. A recreational team from East Hants, a town in the Sidney Mines area just outside of Halifax, was formed in 1986 and joined the university league for exhibition games. Ice time cost the university teams nothing, but access was haphazard, with the women being slipped into the spaces in the men’s schedule. In 1982 St. Mary’s University won the provincial championship and went on to the first national championship. The next year Dalhousie represented the province, followed the year after by Acadia University, which has dominated the league since. At the national level the Nova Scotia teams never fared better than eighth place. In 1989 Dalhousie folded due to lack of leadership, and for the remaining teams competition dwindled to an occasional regional tournament. A Nova Scotia team did not return to the national championship until 1995 when two all-star teams competed against one another to represent the province.

By 1994 the Canada Winter Games program at last rejuvenated the women’s league. The league of four teams, which had floundered since the late 1980s, was now bolstered by three other teams: the Halifax Breakers, Shearwater, and the Nova Scotia Natives, a team composed of women from two Micmac reserves in the north-central Truro region of the province. An eighth team from New Glasgow, a former steel industry region two hours northeast of Halifax, joined the league the next year.

It was no coincidence that the New Glasgow senior team sprung up when it did. Since the first Canada Winter Games in 1991, New Glasgow has boasted the fastest-growing girls’ minor league in the province. Brenda Ryan, the first woman in the province to attain the Advanced level of coaching, saw a long-awaited opportunity to kick-start the game in her region. Four girls from the area were selected for the 1991 Nova Scotia team, and two years later, when the program for the 1995 Canada Winter Games began, minor hockey officials decided to base the training in the New Glasgow area. Ryan used the girls who had made the provincial team to entice others to join. After the provincial team was selected, its members travelled to the six towns that populated the region, playing games against boys’ teams. Ryan drew local girls into the game by encouraging them to drop the puck at the start of games, distribute prizes and sell tickets at the doors. “I just kind of jumped all over it [the opportunity the Games offered] and took it home,”17 Ryan recalls. By 1995 seventy girls formed an active league of three minor teams and one senior team; five years earlier none had existed.

The success of the Canada Winter Games showed to young women—many of whom had been herded into ringette at an early age—that they could be an active part of Canada’s national game. The local minor hockey association helped to set the necessary conditions for the growth of the female sport by giving female players a magnanimous reception. The Pictou County Minor Hockey Association opened its league to the female teams in 1991 and even banned body-checking from male-female games at the bantam level to help the Games’ team train under the nointentional bodychecking rule, which governed female hockey. Consistent ice times have ensured the league’s continuation.

The revival of the female game in Nova Scotia has also attracted hockey scouts from American universities. Some of the province’s better players have been enticed south with lucrative scholarships. Other talented players have gone west to attend Concordia University’s exceptional hockey program or have moved on to the high-performance female hockey program at Calgary’s Olympic Oval. The better players who do not leave the province generally compete on boys’ teams. In Halifax, for instance, girls have been permitted to play on boys’ teams since 1973 and many prefer the male teams to which superior coaches traditionally have been drawn.

A persistent barrier to the female sport’s expansion, however, remains the indifference of the Nova Scotia Minor Hockey Council, particularly with regard to ice time for girls. As Gary Smiley, the representative of female hockey since 1992, puts it, “They support it where it is but haven’t done anything to promote it. Their attitude is, ‘You deal with it.’”18 Although the council has officially backed integrated hockey province-wide since 1984, it has done nothing to reach girls who may want to play but do not realize they can join the boys’ leagues, Of the total sixteen-thousand registered minor players in the province, one thousand are girls. Sixty percent of these girls play on the girls’ teams that have been formed since 1991.

The passive resistance to female participation in minor hockey is particularly pronounced in the Halifax-Dartmouth-Bedford area, a ringette stronghold in Nova Scotia. While female hockey has spread southwest down and across the province from Cape Breton to Shelburne, it has completely bypassed the metro area. The metro area’s hockey association, the Sackville Minor Hockey and Ringette Association, automatically guides girls who approach the league into ringette. As a result, not one minor female team exists in the urban centre. When Smiley expressed his concern over the lack of opportunity local girls have to play hockey, association representatives responded that they did not want to sap ringette. “It was just an excuse and a pretty lame one,” says Smiley, whose daughters play hockey. “I said we’re in this for hockey, let ringette look after themselves.”19

Of all the Atlantic provinces, Newfoundland, a province beleaguered by economic depression and isolating winters, has experienced the greatest difficulty in fostering the growth of female hockey. Its senior team has not competed in the national championship for eight years, mainly due to inadequate ice time. In 1988 its league consisted of five teams. But by 1991 the number of teams had dwindled to three as practices and games were pushed later and later into the evenings to accommodate men’s teams. The prohibitive costs of flights—it costs more than $10,000 to fly a team of twenty to another Atlantic province—has meant that female players cannot compete outside the province. Travelling between cities on the island itself is problematic: a ten-hour drive separates the two largest centres of St. John’s and Corner Brook.

Because senior teams have not fared well, Georgina Short, Newfoundland’s female hockey representative since 1991 and its highest qualified female coach, has directed most of her energy into the minor level. Since 1995 Short has received no financing for girls’ hockey from the Newfoundland Amateur Hockey Association. Although the association has never restricted her efforts to include girls in its leagues—boys’ minor teams in the province have been open to girls since 1970—forming girls’ teams has proven problematic. Fifty-one local hockey associations dot the island, but distances between communities can be offputting to a girl whose only all-female option is a two-hour drive away. For the girls who were selected for the Canada Winter Games team, distance proved to be even more of an issue. Some live in Gander, which is a four-hour drive from St. John’s; others live in Badger, a six-hour drive from the capital. The team’s talented goaltender, Bonnie Stagg, resides in Labrador and was fortunate enough to hitch a ride on an Armed Forces flight to try out for the team.

In 1995 approximately 400 girls played hockey in this province of 580,000, compared with almost 10,500 boys. Forty percent of the girls play on one of twelve female teams; four are senior teams and eight are junior ones. Interestingly, in 1995–96 the minor hockey association in St. John’s agreed to rid the female minor teams of the upper age limit of nineteen in order to ensure that women could continue playing at the convenient time scheduled for minor hockey. Georgina Short says that many of the fathers involved with the association now have daughters who want to play and at last comprehend the need for unique guidelines to protect female inclusion.

Compared with their Western neighbours, hockey enthusiasts struggling to gain opportunity for female players in the Atlantic region have endured a long and often discouraging battle. Not only have they had to contend with the adverse elements and the isolation that come with the geography of the region, they have also had to face indifference to the inclusion of girls. It is heartening that the number of players is now on the rise. But what is most meaningful is the undying belief in the need for sports equity. The legacy of female hockey has survived and been passed on to the present generation, but so, too, has the conviction that girls should and must be given the same chances in life as their brothers. In a region of small victories, these are not insignificant ones.

Nor are the victories of Quebec female hockey. While the number of Quebec players is still low in relation to the province’s population, female players’ talent and zest has had a pronounced influence on the sport nationally, propelling the level of play to new heights across the country. Women’s hockey organizers in Quebec have initiated a bold all-star program to nourish this talent, a program that those in other regions have not dared to request. With the Quebec Ice Hockey Federation at last supporting female inclusion, Quebec is pulling ahead of the game at the elite level. It not only supplies the national team with exceptional players, but it has also triumphed at the national championship since 1994. The lesson Ontario and the rest of Canada would do well to learn is that extraordinary things can be accomplished when women—athletes and organizers alike—demand as much from the game as they do from themselves.