I am ten years old and have been playing hockey for five years. I am quite a good player and was just chosen as one of the top ten female hockey players in Mississauga. While I was at the Olympics [1988] I saw six hockey games. I did not see any women’s hockey teams. When I get older, I want to be able to compete in hockey with other countries from all over the world. I want the chance to stand on a podium and know I am one of the reasons they are playing ‘O Canada.’ Will I have that chance? If not, could you please let me know why? I will try to understand. Also, if the answer is no, is there anything you can do to change that. I don’t want to give up my dreams.

(Excerpted from Samantha Holmes’s letter to Prime

Minister Brian Mulroney, 15 March 1988.)

THE SNOWY PEAKS OF THE Japanese Alps overlook Nagano, the site of the 1998 Winter Olympics. In this tourist area famous for the beauty of its mountains, forests and lakes the first women’s Olympic hockey teams will step onto the ice and into sports history. Yet the story of how they reached that moment—how they arrived at the pinnacle of amateur sport—will be known to only a small number of devoted hockey fans. A new class of hockey is emerging and each player is vividly aware that the success of women’s hockey at these Olympics could be their passport to a future expansion of the game.

The decision by the International Olympic Committee (IOC) to accept women’s hockey as an Olympic sport was due to a combination of factors, the first of which was timing. In the late 1980s the IOC began to express interest in adding more Winter Olympic events. As of 1988 there were only 46 winter events compared with the 260 in the Summer Games. A second factor in the decision was continued pressure from women’s sports associations, and from individuals, for equitable female participation in the Games. There were also several committed and visionary members of the International Ice Hockey Federation (IIHF), the international governing body for hockey, who were determined to build on the growing popularity of women’s hockey, and they aggressively lobbied the IOC and hockey federations for Olympic participation. The fact that the IIHF was flush with additional revenue from a new television contract for the men’s world championship only helped the cause. Gord Renwick, the IIHF vice-president of marketing from 1982 to 1994, and a sixteen-year veteran of international hockey, was keen to activate an Olympic plan that included women’s hockey while the money was still available. “The money was there so we could make it happen,” says Renwick. “If we had to cut [men’s hockey] programs, we would never get approval. Once you get on the road to the Olympics you can get IOC funding and government support.”1

The IIHF is the sole voice for women’s hockey internationally. Founded in 1908 and based in Switzerland, it is a small organization with an international volunteer board representing fifty-four member countries. The Federation provides administrative, financial and technical support for twenty-six annual tournaments, which include the men’s senior, men’s junior, and women’s world championships. Despite its broad mandate the IIHF is not known for its marketing or management expertise. On the contrary, critics have accused it of poor organization and a somewhat crippling lack of imagination. As one source, who did not wish to be identified, explained, “They don’t have any real plan. They just go from meeting to meeting.”

For most member countries men’s hockey is the priority. Indeed, women’s hockey is often viewed as an anomaly and many IIHF members fail to comprehend why women even want to play the game. By 1992 about twenty-five countries offered women’s hockey, and most of their national teams were not formed until the late 1980s and early 1990s, although in several countries women had been playing the game for four or five decades—despite the lack of societal approval or federation recognition. But women’s hockey in many other countries is still regarded with some hostility or, at best, considered a curiosity. Organizers of male hockey resent the competition for federation money and precious ice time, especially in cash-poor countries such as Russia. It is important to remember that in most countries women’s hockey is a young sport. Outside North America it is only about ten to fifteen years old. As Jan-Ake Edvinsson, IIHF general secretary, puts it, “Except in Canada where [hockey] is a religion, it is not [as popular] in other parts of the world.”2

Until the late 1980s the IIHF was oblivious to the women’s game. The Ontario Women’s Hockey Association (OWHA) prodded it into action when it hosted the first world tournament in 1987. For Edvinsson, this tournament was critical because it spawned two official IIHF women’s championships: the European in 1989 and the World in 1990. The IIHF was quick to incorporate the women’s game into its organization: it wanted to prevent a separate international women’s hockey federation from forming, as had happened in field hockey. By 1991, after two world tournaments and two European championships, women’s hockey was still struggling with the universal problems of recognition and funding. In addition lack of ice time made it almost impossible to improve the calibre of the game. Without federation funding it was impossible to hold events that could attract media attention and sponsorship. Given its inferior status and poor financial condition, it’s not surprising that to this day the calibre of women’s hockey varies dramatically from country to country.

Gord Renwick, Canada’s IIHF representative, pushed hard for Olympic status, recognizing it as an essential catalyst which would drive the game forwards at many levels. Although support for women’s hockey within the IIHF was limited, Renwick and several IIHF colleagues aggressively lobbied both the IOC and member organizations for two years. Renwick, with help from Murray Costello, the CHA president, led the drive for Olympic status; the only support came from Norway.

In April 1992 two IOC representatives were dispatched to the world championship in Finland. Surprised and impressed by the female players’ speed, playmaking and intensity, the IOC announced in July 1992 that women’s hockey would become a new Olympic sport. The IIHF then pushed for the game’s inclusion in the 1994 Lillehammer Olympics. The Norwegian Olympic Committee (NOC) refused to accept women’s hockey, however, citing lack of facilities and funds: the committee claimed it would need US$1 million to build the necessary arenas. Despite offers by the IIHF and the Norwegian Ice Hockey Federation to pay for all accommodation and transportation of teams, the NOC did not relent. The decision was a painful blow to many of the older players, who realized they had probably lost their last chance of playing in the Olympics.

In preparation for the 1998 games, Renwick opened negotiations with the Japanese Ice Hockey Federation and the Japan Olympic Committee, hoping to have women’s hockey included in the 1998 Olympics. This was not an easy task. As the host country, Japan would receive an automatic entry into the Games, but the Japanese have not been successful in the game: their national women’s team has qualified for only one world championship since 1990. “There was a lot of resistance to women’s hockey in Japan. The organizers didn’t want to pay to host another sport and besides that, the Japanese don’t have a strong women’s hockey program,” recalls Glynis Peters, manager of women’s hockey at the CHA. “Now they will have to finance an entirely new sports operation to bring their team up to Olympic standards in a few years. They were really reluctant to commit to that.”3 A crucial part of the negotiations regarding Olympic inclusion therefore involved assistance from the CHA to create an exchange program that would send Canadian coaches to Japan and Japanese players to Canada. The Nagano Committee also insisted that the IIHF should pay for food and accommodation for five of the six teams in the Olympics. In the end Renwick’s hard work paid off. On November 17, 1992, the IOC announced that women’s hockey was accepted for the 1998 Olympics.

With the Olympic imprimatur women’s hockey carried new status. The impact of this status reverberated throughout both national and international sports organizations. The IIHF set aside about Cdn$1.5 million to fund competitions from 1995 to 1998, including the Olympics, in order to elevate the level of play internationally.4 The first world event to be instituted was a badly needed Pacific Rim Women’s Hockey Championship to be held in 1995, 1996, and then every two years after the Olympics. This meant that the two active Asian teams, China and Japan, which had lacked serious competition, would now face the two top teams, Canada and the United States, at least twice before the qualifying world championship in 1997.

The IIHF also decided to hold consecutive European championships in 1995 and 1996. This European competition serves as a qualifying tournament for the biennial world championship in which the top five European teams compete against Canada, the United States and the winner of the Asian Cup (China or Japan). In 1989 ten teams registered in the A Pool for the European championship, but to minimize expenses the IIHF only allowed eight teams to participate, and in 1991 a B Pool, consisting of six teams, was added. Two years later, the B Pool increased to eight teams, reflecting the quest for Olympic status. The Olympics has also motivated countries to create their own international competitions. Hungary, for instance, established a tournament with Switzerland, Norway, Germany and Denmark. In 1995 even Italy, a weak hockey country, launched a new tournament, inviting Switzerland, Germany and France. China announced its new fivenation tournament to be held in January 1996.

While the IIHF had expanded the number of competitions in preparation for Nagano, it still needed to address matters affecting the future of the game. Bodychecking has proved to be a contentious issue worldwide. In competition at the national level in China and some European countries bodychecking is permitted, but has not been sanctioned by the European championship rules. Despite the European ban, at the first world championship in 1990 the IIHF insisted on bodychecking, pandering to the prevailing notion that real hockey must include tough physical play. This insistence on bodychecking, combined with the vast difference in skills between the Europeans and the North Americans, resulted in injuries: several players had to be hospitalized. Consequently, bodychecking was disallowed at the world championship in 1992, and the policy is not likely to change prior to the Olympics.

In Japan, the US and Canada, women have played hockey since the mid-1980s without bodychecking. The Canadians and Americans had good reasons for removing bodychecking: most female players had not had any experience in minor hockey and had never learned how to bodycheck properly. As well, in the 1970s and 1980s a fifteen-year-old might find herself playing against a twenty-five-year-old, because there was no minor or junior hockey for girls in many communities. As a result, the skills and ages of the players have varied dramatically, resulting in too many injuries.

Although bodychecking has been banned in IIHF events, body contact is still very much a part of the game. This has caused confusion among players, coaches and referees since the point at which body contact becomes bodychecking has never been precisely defined. The IIHF bodychecking rule states that a penalty will be given for “any overt or intentional contact that is designed to apply physical force to a player.” The key words are “intentional and overt,” which would seem to mean physical force applied against a player whether or not she has the puck. The confusion occurs because referees tend to call more bodychecking penalties in the less important early games of world tournaments than in the semifinals or the final, leaving players and fans uncertain about the exact status of bodychecking. The only attempt at clarification made by the IIHF was a video produced in Canada in 1995 that purports to show the difference between bodychecking and incidental body contact.

The general feeling among many players is that the rein-statement of bodychecking would make their game more like men’s hockey, and thus it would gain in respect and credibility. Many women also genuinely like the physical rush they get after a solid hit. Yet there is also a widely shared fear that women’s hockey could degenerate to the same level as male hockey, in which bodychecking is used to compensate for lack of skating and passing skills, favouring larger and stronger players, forcing smaller players from the game. After the 1994 world championship Germany, whose players were less skilled, was one of the countries pressuring the IIHF to rein-state bodychecking. Germany ranked sixth in the tournament and was the second-most-penalized team, with fifty-eight penalty minutes after just four games. It is possible that body-checking could return to the women’s game when the discrepancy in skill levels lessens, says former IIHF rules committee chairman, Gord Renwick. If bodychecking returns to the game internationally it means young girls will have to be taught how to bodycheck from an early age. In order for this to happen, however, most countries would require better and more consistent competition, improved coaching and more ice time.

In the meantime, the US, the silver-medalist in the last three world championships, is bursting with first-rate, highly motivated players who pose the greatest threat to the Canadian team. With almost 18,000 registered club players and an estimated 10,000 girls and women playing on male teams the US has a solid base of talent to produce a contender for an Olympic gold medal.5 Despite the relatively large numbers, since the first world championship in 1990, the US team has only managed to maintain their ranking as number two in the world. To the surprise of American fans, Team USA even lost to Canada’s rookie national team at the Pacific Rim Tournament in 1995 and again in 1996. Moreover, countries such as Finland, Russia and to a lesser extent China are hot-housing (practising together eight to ten months a year) their teams and could well topple the US at the 1998 Olympics.

Some of the blame for the precarious situation of the US team lies with USA Hockey, the country’s national hockey organization. In 1989 USA Hockey launched the national team program. Development camps were set up for two age categories: one brought together eighty players aged fifteen to seventeen, and the other, senior, camp had forty players over eighteen. The selection and training of coaches to run the camps was haphazard and inconsistent. National scouting and evaluation, even in 1994, was still erratic. Players have complained about team selection decisions being left to the last minute, and scanty advance information about upcoming events. Team USA, although a definite contender for an Olympic gold medal, has not been a priority for USA Hockey. The female team appeared at its first Olympic Festival in 1993 but was absent in 1995, even though expenses for this event are paid by the US Olympic Committee. Art Berglund, national team director, explained that financial constraints had made it impossible for the women’s team to participate (although there was enough money available for four regional men’s teams to attend).

In 1995, after four losses to Canada in world women’s hockey events, the US realized it had to bolster its national team program. USA Hockey coaching director Val Belmonte was dispatched to the 1995 European championships to scout the competition. That summer, USA Hockey held open try-outs in four states. To cultivate younger players, an annual week-long camp for under-17 players was launched at Lake Placid; it will run annually until 1998. USA Hockey also arranged an under-18 tournament with Russia and a Quebec all-star team, to be held in March 1995 and 1996.

Despite these advances observers of female hockey are concerned with the coaching situation in women’s hockey. No initiatives to mentor female coaches exist. “We feel that women coaches are being pushed aside in favour of male hockey coaches since the men’s national team haven’t won a medal since 1980,” notes Lynn Olson, former section director for women’s hockey.6 Since the NHL controls hockey in the Olympics, the only chance for an amateur coach to participate in the Olympics is with the women’s team. As of 1995 twenty-four coaches (mostly male) expressed interest in the women’s team. In June 1996, USA Hockey announced Ben Smith, coach of men’s hockey at Northeastern University, as head coach of the women’s Olympic team.

The management of Team USA has been less than satisfactory, but the team does include some outstanding players. Two

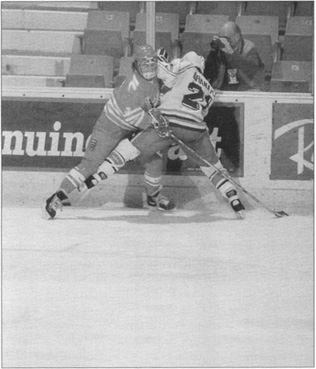

Team Canada’s captain France St. Louis (left) fighting for the puck against Cammi Granato, Team USA.

players who have set the standards for Team USA are Cammi Granato and Karyn Bye. Granato, a five-time national-team star was voted most valuable forward in the 1994 world championship, with twelve points in five games. Twenty-six years old in 1998 she packs speed, accuracy and smarts into her lean 5 ft. 7 in. (170 cm), 140 lb. (65 kg) frame. Beginning at the age of five Granato played hockey with boys until she was a junior in high school; she was usually the youngest player on the ice and the only girl. “Guys would take runs at me even if I didn’t have the puck,” Granato remembers. “[On one occasion] my coach told me that the other team were told to hit number 21 as hard as they could the first period, so we switched jerseys.”7 At Providence College Granato won two Lady Friars Awards, one as the all-time leading point scorer, with 245 points, and the other as all-time leading goal scorer, with 135 goals. She was also named Eastern Collegiate Athletic Conference (ECAC) player of the year for 1990, 1991 and 1992. “There is no more deadly offensive threat in the league than Cammi,” says Margaret Degidio-Murphy, coach at Brown University. “She is a force, a very cool character under pressure.”8

Teammate Karyn Bye’s approach to the game is just as committed. A T-shirt she often wears sums up her devotion to the game: “Hockey is life, the rest is just the details.” As Bye explains, “If there was no hockey, it would be like waking up and not having air to breathe.”9 A member of the national team in 1992 and again in 1994, this 5 ft. 8 in. (174 cm), 165 lbs. (71 kg) woman is a strapping forward with a blistering slapshot. After an outstanding college career with the University of New Hampshire Wildcats, she joined Montreal’s Concordia University in 1994 and led her team in scoring with 86 points, including 43 goals in 40 games that same year.

Both Granato and Bye played with boys as they were growing up because minor hockey didn’t exist for girls in the US. National championships were initiated in 1975, but twenty years later, there were only ten states participating. Michigan, Massachusetts and Minnesota have the strongest programs for girls and women, but many of the participants have never had the chance to play minor hockey, or played only with boys. In 1994–95 there were just under 500 teams registered with USA Hockey, plus another 150 college, high school and prep school teams. The popularity of female hockey shot up after the 1990

world championship: registration went from 5,533 players in 1990–91 to 17,537 in 1994–95. In addition, an estimated 10,000 girls play on boys’ teams. Despite the extraordinary growth, the female game still accounts for less than 10 percent of the 400,000 registered players.10

Management of the women’s game is weak. USA Hockey, which was founded in 1951, lists four executive directors among their staff of forty-five, but as of spring 1996 there was no manager appointed specifically to oversee women’s hockey, although it did mention that it would try to hire someone before the Olympics. Volunteer regional directors work with staff to coordinate the women’s game. USA Hockey held two international women’s hockey tournaments. When it hosted the 1994 world championship in Lake Placid promotion was dismal, and included a full-colour program that featured male players on the cover.

Although USA Hockey made amends for its faux pas in 1995 and produced a glossy colour shot of two female hockey players on the Pacific Rim program, it was the same lacklustre attitude towards female hockey that forced the national teams from Canada, the US, China and Japan to play their first Pacific Rim championship on a small practice rink rather than a regulation international rink. The arena seated only about 1,700 people—more evidence of USA Hockey’s lack of confidence in the women’s game. Promotion, once again, was abysmal. For example, a huge banner that should have emblazoned the championship’s name across the exterior of the rink was strung haphazardly over the bleachers at one end of the arena.

USA Hockey, like many other hockey federations, would benefit from a good sports equity policy. As mentioned previously, Title IX has been the legal vehicle for sports equity in the US since 1972. The law applies to federally funded schools and universities and is aimed at prohibiting discrimination on the basis of gender: in plain words, it requires US schools to give male and female athletes the same opportunities. The law has several components: if women make up half of the student body, then fully half of the varsity athletic sports budget must be allocated to women’s sports, or the school must otherwise demonstrate that it is meeting the level of interest of female athletes or is expanding women’s programs. Schools had until 1978 to comply with Title IX, and by that year women’s teams accounted for 33 percent of the nations college athletes. “Unfortunately, that’s where we have remained for the last fifteen years,” says Donna Lopiano, executive director of the Women’s Sports Foundation. “Thousands of cases have been filed related to gender equity and the court has consistently upheld Title IX.”11 “Males over fifty years old are our toughest opponent,” says Lynn Olson, Minnesota’s women’s hockey representative and a former USA Hockey section director.12

Title IX has had some impact on women’s hockey, most recently in the state of Minnesota. In 1994 hockey became a varsity sport for the first time in state high schools and later that year the government instituted ice-time legislation to redress the inequities for girls, stipulating that in 1994–95 15 percent of all rink ice time must be allocated for girls, rising to 30 percent in 1995–96 and 50 percent by 1996–97.

Since the new policy, girls’ hockey registration has almost doubled in Minnesota, jumping from 119 female youth teams in 1994–95 to 200 in 1995–96. In the fall of 1995 Minnesota introduced varsity hockey in its state university. Lynn Olson, the state hockey representative and a former USA Hockey section director, maintains that college hockey will increase dramatically in the next five years because of Title IX. Even if schools do not add women’s hockey voluntarily, some schools may do so through fear of lawsuits. Women are still fighting for equal rights and the same old excuses abound. “‘We cannot afford to convert our programs’” say athletic directors, but they can still afford ninety boys on a football team,” says Lynn Olson.13

Scholarship allocation is another area of glaring inequity in college women’s hockey. In 1989 only three colleges offered scholarships for women. By contrast, men collected an average of eighteen scholarships per college per year. The men’s game has developed accordingly, with fifty-one colleges and universities playing Division I hockey, thirteen Division II and fifty-nine Division III. Many universities in the 1970s made token concessions to women by allowing community teams to carry the varsity banner, but there was still no money for travel, equipment, coaches, trainers or practice time. In 1994 twenty-three universities and colleges still had only club teams.

The exception to this pattern is the Eastern United States, which has led the country in women’s college hockey. Since 1976 six Ivy League schools have competed annually for the Eastern College League championship. The first Eastern College Athletic Championship (ECAC) was held in 1984. The ECAC was the first conference to sponsor an intercollegiate women’s hockey league nine years later. During the 1994–95 season the league expanded to include fifteen varsity teams, with the top eight teams advancing to post-season play.

The number of lawsuits based on Title IX has been increasing since 1990, but change is slow to come. In 1994 the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) set up an equity task force and deemed women’s hockey an “emerging sport.” The NCAA claims that this new status gives the association a way of demonstrating the level of interest of players and schools. According to Donna Noonan, director of championships for the NCAA, if forty institutions sponsor women’s hockey as a varsity sport for two years, then legislation can be drafted to establish an NCAA championship; once the legislation was in place, schools could obtain additional funding. This is not an unrealistic projection since, as of 1994–95, forty universities did have teams, sixteen of which had varsity status. However, the results so far have been negligible. It is Title IX that is really driving the surge in varsity women’s hockey.

Colleges have always been an important training ground for national team players. In 1994 half the members of the national team sprang from the US university and college circuit. If it were not for the NCAA rule, allowing players only four years of college eligibility, the numbers would be even higher. As it is, after college female players have nowhere to play. The community leagues offer inferior competition, and as of 1995 only a dozen Senior A teams existed in the US. (In Canada the rules allow post-grad students to play on the varsity team, and a growing number of US national team members have moved to Canada to play hockey at a more competitive level.)

In the meantime USA Hockey, the supposed guardian and promoter of American women’s hockey, continues to scramble forward in its attempt to catch up to Canada and Finland. The goal would appear to be well within reach, given the desire and talent of the players, but the competitive gap is quickly narrowing between North America and the rest of the world. Team USA runs a risk of falling far behind countries that are wholly committed to devoting time and money to the female game.

Although many European teams are progressing rapidly, the calibre of women’s hockey in Europe and Asia remains generally below the North American standard, except in Finland, Sweden and (more recently) China and Russia. One difficulty is that most European countries have only a very small pool of female players (Finland’s registration is the equivalent of that for the province of Alberta). In addition Scandinavian and some European players learned to skate in the mid-1980s playing a different game called “rink bandy,” which is like field hockey on ice. As of the 1996 European championship, the top five teams are Sweden, Russia, Finland, Norway and Switzerland. In a surprise turn of events Sweden took home the gold medal (its first). Russia, the new entry in Pool A, won silver and Finland with five players missing won the bronze medal. Norway and Switzerland ranked fourth and fifth. Coming last place, Germany is now relegated to the B Pool. These European champs, along with the winner of the biennial Asian Cup and the Canadian and US teams, will face off in the Olympic-qualifying world championship in Canada in 1997. The best five teams from that event will then go on to the Olympics.

The 1996 silver medal for Russia was shining proof of just how far this nation has come. While Russia is considered a hockey mecca, Russian women are relatively new to hockey, years behind most of their European neighbours. Moreover, women’s hockey in Russia has some of the elements of a ColdWar spy novel: their star player has defected, political upheaval threatens their funding and infighting plagues the Russian Ice Hockey Federation (RIHF).

Russian women today play hockey in a very difficult climate compared to that enjoyed by men who competed in the glory days of the Red Army teams. The exodus of top male players to the NHL, dilapidated rinks, financial instability and political unrest have left hockey in Russia in chaos. Aside from the Central Army Penguins (a team owned by the Pittsburgh Penguins, which has a merchandising agreement with the Walt Disney Company), most hockey games are poorly attended. Many teams charge US$1.50 per game, and attract at most two or three thousand fans—sometimes as few as two hundred. With the average worker in Russia earning approximately US$300 annually, attending hockey games has become a luxury. In addition to all their other troubles players have had to contend with antiquated equipment. Indeed, in 1992 female teams were still coping with twenty-year-old hockey skates and shin guards made of rolled-up newspaper.

Given the financial and political obstacles in Russia, the future of women’s hockey rests squarely on the shoulders of the national team. In the event of the Russian national team’s qualifying for the world championship in 1997, the RIHF has promised more money: not only to train for the Olympics but also to develop women’s hockey in the future, beyond the national team. The players and coaching staff have kept their part of the bargain, rising from obscurity to second place in Europe in the 1996 European championship. Given the team’s recent success, it will be interesting to see whether the RIHF will keep its promise to channel funds into grassroots women’s hockey after the Olympics.

Olympic status has had some concrete benefits for the Russian game already. Leonid Mikhno, president of the Troika sport club in St. Petersburg and vice-president of the northwest region of the RIHF, created the Women’s Ice Hockey Association of Russia (WIHAR) in 1992. In June of that year, WIHAR held its first event, the White Nights tournament, in St. Petersburg, which was put together with the assistance of the New Jersey-based A&L Management, an event organizer for Russian hockey teams. Desperately needing better competition, Russia invited both Canada and the US to attend. Two US club teams arrived and handily defeated the inexperienced squad from Russia and the two entries from Latvia and the Ukraine.

Despite the defeat, the players’ enthusiasm prompted the WIHAR to assemble more women’s hockey teams. By the end of 1992 there were five teams competing in Russia, one in Siberia, two in Moscow (these were rink bandy teams who also played in hockey tournaments), one in St. Petersburg and one in the central city of Saratov (this team only lasted one year). In January 1993, once again with the help of A&L Management, the WIHAR hosted the Unified Open Tournament for all-star teams from Russia, Latvia, Ukraine, Germany and the US. Five Latvian and five Ukrainian players from the tournament formed the basis for a new Unified Team, the precursor of the Russian national team.

Although the president of the RIHF acknowledged the women’s hockey association, neither financial nor administrative support was forthcoming to the fledgling organization. In order to develop players for a national team the WIHAR desperately needed money to host tournaments and travel to competitions against the more experienced North American teams.

The Russian women’s struggle to join the international hockey community despite financial hardship did not go unnoticed in North America. In a gesture of international good-will, it was the women’s hockey community that came to the rescue. In 1993 the Russell Women’s Ice Hockey Association, located outside Ottawa, Ontario, agreed to host the first International Friendship tournament, an event designed to aid the Russian teams. The Ottawa group arranged transportation and accommodation for the Russian team (in association with A&L Management). Russia’s new Unified Team spent three weeks in the US and Canada, facing off against Senior A and B teams. A&L Management sold Russian T-shirts and hockey jerseys at each game to help pay for the trip. In April 1994 the Boston Women’s Ice Hockey Fund, a new not-for-profit organization dedicated to promoting women’s hockey, raised US$7,000 to help pay for the Russian national team’s second North American tour; they also equipped the team with fourteen pairs of skates.

By spring 1994 women’s hockey at last had caught the attention of the Russian Federation. That year the new president of the RIHF decided to create a women’s division in Moscow, with a committee to oversee women’s hockey and promptly told the WIHAR it was simply no longer needed. The Russian Federation then turned its attention to the Olympics. It chose thirty of the best players from Russian teams and brought them to Moscow to live and train at a sports school. The team will stay together for three years and practise two to three hours a day, eleven months a year. Some are paid (unconfirmed reports suggest US$100 per month) and some are given lodging. In many cases these women, some of whom are girls as young as fifteen, have to travel huge distances, leaving behind their families and friends. Few Russian mothers can afford to visit their daughters in Moscow and many are unhappy that their daughters are involved in what is widely regarded as an unsuitable sport for women.

Life on the national team is difficult. The new coach Valentin Egorov (whose credentials include coaching a Russian Army team), screams at his players and sometimes holds three on-ice practices daily, each lasting two hours. If players don’t play well, he docks their pay. The approach has had a demoralizing effect on team members. After watching several

Russian national team, US exhibition tour, Marlboro, Massschusetts, March 1995.

games, one Canadian coach remarked, “There was no emotion on the [Russian] bench and no team spirit.”14 Despite the punitive approach, in 1995 the Russian national team won the B Pool in its first European championship, allowing Russia to move to the A Pool in 1996, where its second-place finish was a remarkable feat for a country that only four years earlier had only five women’s teams.

Centre Ekaterina Pashkevitch, an MVP in two European and one world bandy championships, is the pulse of the national team. Towering over her teammates at 5 ft. 10 in. (178 cm) and 190 lbs. (86 kg), this twenty-one-year-old accounted for most of the national team’s goals from 1994 to 1996. Pashkevitch took to the ice at age three, playing pond hockey with boys. By age seven, she was recruited by a boy’s school coach and played in boys’ hockey until she was a teenager. She also played professional rink bandy for eight years with her hometown Moscow club. There, in the early 1990s, she became one of the very few paid female athletes in Russia, earning US$50 a month. As a freshman at the prestigious sports institute in Moscow in 1993, Pashkevitch realized she needed stronger competition to improve her hockey skills. After travelling to North America with the national team, she moved to Boston, Massachusetts, in 1994 with the help of Julia Ashmun, director of the Women’s Ice Hockey Fund. In August of 1995 she secured a job as head coach of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology club team. In 1996 she made the all-star team and was also voted top scorer in the European championship.

Although Russia beat Finland in the 1996 European championship, Finland is still considered by both Canada and the US as the most formidable team in Europe. The country has won four of the last five European championships and placed third in the 1990, 1992 and 1994 world championships. Finland is the best example of a country that has pumped up its national team program. In the fall of 1994 the Finnish Ice Hockey Association (FIHA) finalized its Olympic plan: in order to surpass their North American rivals, the national team coaching staff now works with thirty-five to forty athletes, meeting six times a year to test physical and psychological fitness, practise dryland training and work on team building. Interspersed with these training sessions were practice competitions against Russia, Sweden and the US to prepare the young Finnish squad (as of 1995 all players were under twenty-three years old) for the qualifying European championships in March 1996. Their commitment is paying off. After watching the Finns score four goals in seven minutes in their first game at the 1995 European championship, sweeping by every team in the A Pool, Val Belmonte, director of USA Hockey Coaching Program, heaped praise on the offensive dynamos. “Their tempo and intensity is very high,” he raved. Belmonte rated the Finns number one, the team with the best chance of beating Canada. “They are training like world-class athletes. Now they are better than the US,” reports Belmonte.15

Female hockey players laced up their hockey skates for the first time in 1970 in Southern Finland, the hockey heart of the country. By 1983 ten teams participated in its first national championship. Registration rose after the first world championship in 1990, increasing from about five hundred players to sixteen hundred in just four years. In 1994 FIHA established a league for girls aged fifteen and under. Although total registration has improved, by 1995–96 it still totalled less than two thousand. Female hockey teams continue to cope with poor access to both facilities and federation financing. Games are limited to fifteen-minute periods, except in the top senior league.

The Finnish women play swift, free-wheeling hockey. The lightning-fast centre Riikka Nieminen personifies the Finnish spirit. An allround athlete Nieminen has won national championships in bandy, rink bandy, hockey and baseball. The US scouting report on this small but wiry speedster noted, “She has a very quick start, drives to the net and reads the ice very well. She’s mean, with a competitive fire.”16 Having joined the national team in 1989 at the age of sixteen, Nieminen made the world championship all-star team in 1992 and 1994. (She missed the 1996 European championship due to knee surgery.) Since minor hockey did not exist for girls her hockey experience began at age seven with a boys’ team.

But Nieminen’s success has its disadvantages, the most annoying of which is a “fan from hell,” who has followed her to two world championships, two European championships and all her local competitions since 1991. He writes letters, leaves phone messages and at one point even issued a jealous threat when he saw her with a male friend at a hockey gathering. In Lake Placid in 1994 he wore a Nieminen hockey shirt to all the Finnish games.

Another outstanding Finnish player Toronto fans may remember is number 17, Sari Krooks. Krooks played with the Senior AA Toronto Aeros from 1989 to 1992. She has been one of the top five scorers in Finnish hockey and a member of its national team since 1989. Krooks can literally skate circles around many players and is known for her intensive dryland conditioning program. After giving birth to her first baby in 1993, she was back on the ice in just three weeks. Krooks now lives in Ottawa and plays hockey with a local Senior A team, the highest level for female players in the Ottawa area. In an attempt to maintain her skills, in 1995–96 Krooks commuted five hours to Toronto on the weekends to play once again for the Aeros. She suffered a broken leg late in 1995 and was unable to play for Finland in the 1996 European championship. She is expected to play for Finland in 1997.

The success of the Finnish national team is not surprising since hockey is Finland’s national sport, followed by soccer and rink bandy. Men, however, still dominate the ice, with women

Sari Krooks, one of Finland’s national speedsters at 1994 world championship.

accounting for less than 5 percent of the 43,000 registered players. In 1995 each player on the men’s national team was paid US$20,000 when it won the world championship. So far

the women have received no reward. In the amateur world of women’s hockey, that kind of bonus would enable many players to train full-time for the Olympics. It remains to be seen if Finland will express a similar financial commitment to female hockey.

Finland’s southern neighbour, Sweden, launched its first official women’s hockey league in 1981 in Stockholm. Two years later, the Swedish Ice Hockey Association (SIHA) established a separate ladies’ committee but dissolved it within only two years, opting instead to lump women’s hockey in with other male hockey committees. Federation support for the female game is notably absent among several key members of the SIHA. The chairman of the SIHA commented in 1993 that although women’s hockey is in the Olympics, it is not a sport for women. Instead, he suggested that women should ride horses. Ironically, rather than discouraging women from playing, his sexist remarks generated outrage in the media giving a boost to the women’s game. Despite anachronistic views such as these, financial incentives keep SIHA interested in the women’s game. The Swedish government aims to reach a 40 percent participation level for women in all sports and it provides funds to sports associations that encourage female participation.

The number of female players in Sweden is rising, but the universal problem of access to ice time has not been solved. Women’s games have been cut from three to two twenty-minute periods, to limit ice time. Short practices for the senior elite teams are held only two or three times a week. By 1994–95, only 1,152 players were registered, with thirty-two teams competing in the national championship. The SIHA has taken some steps towards remedying this, however: that same year it launched a hockey program for seven- to fourteen-year-old girls in Stockholm. (Girls aged six and under play with boys.) To encourage more girls to play, Sweden removed body-checking from the women’s game in 1994, joining a growing number of countries which are adopting the IIHF rule.

Nacka is one of the most successful senior teams in Swedish hockey. They enjoyed an unprecedented winning streak between February 1982 and March 1987, losing only one game, and triumphed at the national championship for five consecutive years. The team also produced thirteen of the players on the 1987 world championship team. Despite this crop of talent the Swedish national team only managed to place fifth at the 1994 world championship. Disappointed with this showing, Sweden attended two extra tournaments against Russia, Finland and Norway in 1995 and 1996 and added training camps each year prior to the European championship in March. These efforts paid off: Sweden placed first in the 1996 European championship.

Norway is the third Scandinavian country with women’s hockey but has not enjoyed the same success as its neighbours. This small country of four million people proclaims soccer as its top sport, and its twenty ice rinks in the country are primarily devoted to boys’ and men’s hockey. The first female teams were formed in 1987. The national championship followed two years later, but in 1994 registration seemed to have peaked at around four hundred players. In spite of these disadvantages Norway still managed to place fourth in the 1996 European championship.

The Norwegian women’s game owes its advancement largely to the efforts of one man. Herman Foss, the former managing director of the Norwegian Ice Hockey Federation and member of the IIHF women’s committee, has led a one-man campaign to promote the sport. In 1988 he launched the annual Nordic Cup tournament, inviting Denmark, Germany and Switzerland to participate. In 1993, frustrated by the lack of interest from both his colleagues and the public in women’s hockey, Foss hired former US national team member Ellen Weinberg to spend three months assisting coaches of the Norwegian national team and promoting the game. Weinberg visited communities, introducing national team players and holding clinics. The press picked up the story, because Weinberg was a foreigner and part of the highly rated US national team.

Switzerland, another small country, has had to contend with a very conservative and unsupportive attitude towards female hockey. “Hockey in Switzerland is prehistoric,” complains the former assistant coach of the national team, Kim Urich. “There has been no change since 1990.”17 As a result, the sport has grown slowly: player registration as of 1994–95 totalled only 616, compared with 25,423 boys and men.

In most countries, individual members of the national women’s hockey teams must “pay to play,” and in spite of Switzerland’s wealth, the Swiss team is no exception. Even in 1995 each player had to cover the cost of her own air fare to the European championship, the annual Christmas Cup tournament, and the five selection camps—expenses that added up to US$1,000. According to the soft-spoken national team manager and player Barbara Miiller, some Swiss hockey fans have suggested that since “the men’s national team get a lot of money and they don’t place, let the men pay, maybe they will play better.”18

The first Swiss women’s team took to the ice in 1980, but it took four years for women’s hockey to be recognized by the Swiss Ice Hockey Federation. In 1986 the first official national championship and Ochsner Cup (an international tournament hosted by Switzerland) welcomed Canada and Sweden. The top Swiss Senior A division is permitted to carry two foreign players. This provision both hinders and helps women’s hockey in Switzerland. Foreign players are usually stronger and often play too large a role in national championship. In the opinion of some observers, they allow the Swiss players to be lazy. But according to Barbara Miiller, foreign players can attract sponsors and if properly coached motivate players to work harder. Muller reports that the Canadian players are heroes to many girls in Switzerland. Foreign coaches, too, can play a critical role in improving teams. In 1995 France Montour, a member of Canada’s 1992 national team, co-coached the Swiss national team to a bronze medal in the A Pool in the European championships—its best effort yet. Amid stiffer competition in 1996, Switzerland managed to salvage a fifth-place finish, the final team to qualify for the 1997 world championship.

In Germany, although women’s hockey sprang into action in 1974, only eight teams competed in the first “ladies” national hockey championship, which was held a decade later. Introducing younger age categories has helped develop minor and junior hockey, and consequently the registration in 1994–95 jumped to over two thousand players, including more than five hundred who play on boys’ teams. But hockey is still not considered acceptable for girls and women by most Germans, and as result, the game is growing only (approximately) 10 percent a year. The senior women’s leagues, however, do play three twenty-minute periods per game—somewhat of a luxury, compared with most other countries.

The German national team has been in existence since 1988 but it has never been strong. In the 1994 world championship it fell to last place. Hoping to develop younger players for the Olympics, the German Ice Hockey Federation added forty more players to its national team selection camp and arranged an under-20 tournament, along with development camps in all provinces. Despite the effort, Germany placed last in the 1996 European championship, failing to qualify for the 1997 world championship, and thus losing its chance to go to the Olympics.

Eight countries compete in the B Pool of the European championship. The ranking for 1996 was as follows: Denmark, Latvia, Czech Republic, Slovakia, France, Netherlands, Kazakhstan, and Great Britain (Austria and Italy have not so far joined the B Pool). Most of the B Pool nations have very few players; Latvia, for example, has only about forty participants. Many of these countries are relative newcomers to the women’s game, most of them starting in the late 1980s or early 1990s.

Opportunities to compete are also meagre in Asia. In alternate years, China and Japan play off in the Asian Cup to qualify for the world championship. Since 1992 China has consistently overwhelmed Japan in the competition to attend these championships. Asian countries were finally awarded an international competition, apart from the world championship, with the launching in 1995 of the Pacific Rim tournament. Exact information on women’s hockey in China is not widely available because access to interpreters is limited and these interpreters offer only basic details, some of which

Members of the Chinese national team at the 1994 world championship, Lake Placid.

are more public relations than information. What is known, however, is that women’s hockey in China plays a different role than it does in European countries. The Chinese see women’s hockey (as they do most sports) as a means to improve their country’s image internationally. Since the men’s team languishes in the D Pool, China is counting on women’s hockey to elevate its international profile. Consequently, the Chinese women’s national team enjoys relatively strong state support. The rate of improvement is impressive given the small number of players (only about three hundred), the paucity of facilities and China’s brief history with the game.

The heart of women’s hockey in China is Harbin, a city of three million and the capital of the country’s most northerly province, Heilongjiang. Here winter lasts for six months with temperatures as low as minus 38°C. Harbin is an industrial city, but it is also renowned as a winter sports resort because of its ice skating, ice yachting and hockey. Harbin is also home to the Chinese women’s national team. Eight of the eleven women’s teams practise in the area’s three rinks (only nine ice rinks exist in the whole country). Hockey is played only here and in only two of China’s thirty provinces. Competition, both nationally and internationally, is limited by the huge distances involved. Only six teams meet at the national championship, which began in 1987.

Like some European teams, the Chinese play with body-checking. China has become increasingly dependent on its physical play, so much so that it has developed an international reputation for excessive slashing and holding. Nonetheless, this young national team seems wildly determined to succeed. A number of players possess good individual skills, and the team’s passing and hockey sense improves markedly with every competition. Spectators are in for an uncommon experience watching these Chinese women with their scarlet uniforms, flying shoulder-length black hair, and constant yelling on the ice. Two players of note have been number 20, Hong Guo, the bold and aggressive goaltender, and number 3, Lui Hongmei, a forward who placed fifth among scoring leaders in the 1994 world championship.

In spite of the dearth of arenas and the limited opportunities to compete internationally, China’s national team is surging ahead of some of the more experienced European teams. Its national team was only put together in November 1991, yet China roared into contention, easily defeating the Japanese in the Asian Cup tournament to qualify for the 1992 world championship. China placed fifth in 1992 and moved up to fourth place in the 1994 world championship. At the 1995 Pacific Rim championship, China even came close to beating Canada in a bruising semifinal game, finally bowing to the Canadians in a shootout by a score of 2–1. In the 1996 Pacific tournament, China was just as rough, leading the four team tournament in penalties. Colleen Coyne, a US player, suffered a broken arm as a result of a Chinese slash in the semifinal. Canada was barely able to escape with another victory, this time beating the Chinese 1–0. It was a wake-up call to the world: “China will be twice the threat in 1997,” maintains Canada’s national team coach, Shannon Miller.19

One of the main reasons the Chinese team has been so successful is the players’ participation in sports schools. Elementary and secondary students who show promise are sent to one of the 2,400 physical culture and sports schools on a part- or full-time basis. Furthermore, the national team practise together two and a half hours each day, Monday to Friday. China is a country desperate for recognition in the world community, especially given its reputation for human rights violations: sports, therefore, play a critical role in its attempts to improve its tarnished international image.

Despite the national team’s growing success, registration for women’s hockey in China, in contrast to many European countries, has not increased since 1988. But opportunities for Chinese women to play are increasing nonetheless. In 1990 women’s hockey was included in the National Winter Games, an event held every four years. Moreover, when women’s hockey was added to the Asian Winter Games (also held every four years) in 1996 in Harbin, China handily defeated Kazakhstan 13–0 and Japan 9–3. The most intriguing development of all, however, is the new Winter Sports Commission started in 1994, an agency that plans to develop ice sports in heavily populated Southern China. The plans are no doubt due partly to China’s success in both short-track speed skating and figure skating.

Canada is also playing a role in developing grassroots hockey in China. Since lack of ice rinks is a major obstacle to the development of hockey, the Pacific Entertainment Group Inc. (PEG) from Toronto, has launched a unique venture. The company’s goal is to construct eight rinks in two cities in Southern China. PEG’s contract also includes teaching ice skating and hockey, employing programs from the CHA and the Canadian Figure Skating Association.20

Jack Grover, president of PEG, envisions his company as the “Wal Mart of ice skating” in China, putting three to four hundred people on a rink at one time. Two rinks, one Olympic-sized, with 2,500 seats, and the other, a smaller one, will open in Shanghai in the fall of 1997. At the rinks, public skating will cost US$3, and include a helmet, skates and a lesson. Once the arena is built, skating will also become part of the school program. For US$ 1, school children will be able to take a lesson and rent a helmet and skates. Furthermore, PEG anticipates 50,000 school kids each year will hit the ice as part of an eight-week “learn to skate” course.

The demographics of this endeavour are staggering. More than 250,000 children attend school within walking distance of the rink. More than 15 million people live in Shanghai, and a total of 225 million people in four surrounding provinces. The opening ceremonies for the first rink will be televised and will feature hockey teams with ten-year-old boys and girls. These children will spend a month in Canada learning to play hockey. Approximately 240 million Chinese own television sets, so millions will likely be watching hockey in southern China for the first time. PEG projects that 100,000 to 200,000 people will be playing hockey within five years.21 The rink will stay open year round (even through the blistering-hot summers), twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, to accommodate those looking for a diversion and respite from the heat. As part of its promotion, PEG even taught the sixty-year-old Chinese ambassador to Canada, his fifty-seven-year-old wife and twenty embassy staff to skate.

China’s Asian counterpart, Japan, has not benefitted from anywhere near as much state support to improve the women’s game. According to Canadian Rick Polutnik, the assistant coach of the Japanese national team in 1995, “Japan is like Canada was fifteen years ago. There are four or five good players on a few teams but no strong league.”22 In fact no regular games take place; there is only one monthly tournament and the national championship. Some teams compete in as few as five games a season.

Women’s hockey in Japan dates back to 1973, when six teams began competing: two in Tokyo, three in Hokkaido, and one in Honshu. In 1978 five teams organized the first national championship. Three years later, the Japan Ice Hockey Federation hosted the first official women’s national championship. By 1995 sixteen teams were competing in the national championship and registration had swelled to sixty-six teams. In Japan’s northernmost island, Hokkaido, hockey and speed skating are part of the physical education program in elementary school. By 1995 Hokkaido boasted nineteen teams and is now famous as the “mecca of skating events” in Japan. Of the almost fifteen hundred players in the country, Hokkaido accounts for a third. Thirteen of the twenty-one players on the 1995 national team sprang from the Peregrines, a Hokkaido-based team. Mr. Tsutomu Kawabushi, the team’s manager is a former national team player and coach, and generously covered two-thirds of the female national team’s expenses at the Pacific Rim championship in 1995.

As is the case for women’s hockey around the world, the ages of players on the senior teams can range from thirteen to thirty owing to the lack of female minor hockey. Girls twelve and under are obliged to play with the boys. In the past inexperienced coaches held practices consisting of mainly skating, with little or no emphasis on passing or playmaking skills, but today this is no longer the case. Women play three twenty-minute stop-time periods, with two-hour practices twice a week. Most players are highly motivated and after every practice, as the culture dictates, they thank their coach and apologize for making bad passes or mistakes.

In order to be a serious contender at the 1998 Olympics, Japan is counting on assistance from Canada. In 1985 Japan sent its first female hockey team to play in Canada and two years later an all-star team came to Canada to play in the world tournament. Furthermore, Rick Polutnik, a former coach with the Canadian women’s national team, has been advising the Japanese national team since 1993 and joined the team as assistant coach at the Pacific Rim tournament in 1995. Japan lost every game, but one week after the tournament both the confidence and the skills of the team had improved dramatically. Japan defeated Polutnik’s Senior AAA team (ranked fourth in their league in Calgary, Alberta). “They were feeling sorry for themselves after San Jose,” explains Polutnik. “I told them I didn’t want to be embarrassed by having them lose to my team. They played like a Canadian team, handling the puck and winning in the corners.”23 Part of the reason for Japan’s losses in world events is the size and age of the national team. The players are small and young with little upper body strength; many of them fear gaining weight for aesthetic reasons. They munch salads before a game while the other teams wolf down pasta and breads. Regardless of the obstacles facing the Japanese team, Japan’s status as Olympic host country puts its women’s team in a unique position. It appears it can only benefit from the overwhelming exposure to women’s hockey in 1998.

The Olympics are the next benchmark in the women’s game, but will these first Games be like the first world championship: much fanfare, then oblivion? Will only the national teams reap the benefits from the Olympics, with no money for grassroots development? And who will champion the women’s game at the IIHF? No one can predict the results because the women’s game is changing too quickly and lacks consistent leadership. The road to Nagano is the second stretch in the drive for international development of women’s hockey. Hockey federations and sports bodies in many countries have already discovered the huge range of talented and ambitious women who love hockey. These female players deserve the chance to play with the same respect, attention and funding given to their brothers.

Finally, Samantha Holmes, the young girl who wrote to Canada’s prime minister about the women’s game, will get her wish to watch women’s hockey in the Olympics. She is one of the new generation of young players who will be inspired to dream of finding their place at the future Olympic Games. These games will be etched in their psyches forever, and friends of women’s hockey have every reason to hope that the Olympic teams will also become part of a groundswell of leadership needed to advance the current gains in women’s hockey. But at the very least, for two weeks female players will be warmed by the Olympic flame, no longer outsiders in the chilly political climate of international hockey.