3. CALYPSO BULBOSA

A. E. Bartram

c/o Lake Hotel

Yellowstone National Park

June 20, 1898

My dearest family,

I apologize for not staying in touch but I have been so involved with my day-to-day routine that there seems little time to reflect upon and report my work’s progress. And yet, as I commit those words to paper, I realize there is much to reflect upon, as well as to report, now that the weather has warmed and the earth is beginning to respond in kind.

We are camped in a grassy meadow above Yellowstone Lake, up the road from the Yellowstone Lake Hotel. Professor Merriam had originally selected a site directly on the lake, but when the wind was not blowing full speed, the mosquitoes were, as Lewis once wrote, “quite troublesome” even this early in the season. So the Professor wisely transferred the camp to this alternate location.

It is an ideal situation. In essence, we have all the benefits of the hotel, including medical and other assistance should we ever be in need of them, without all the expense and bother of being in residence there. We are strategically located, as well, on the Grand Loop, the wagon road which circles the Park’s main attractions, so most of our desired destinations are within a short walk or wagon ride. Of course, such a centralized location leaves us open to regular visits by travellers exploring the Park on their own, separate from the coupon tours. I must admit, I find the constant interruptions trying, but Dr. Rutherford and Rocky and Stony, the two students, all seem to relish the extra company in the evenings, particularly when that company includes Miss Zwinger and her lady friends from the hotel.

That is not to say that Dr. Rutherford and the boys welcome all visitors equally. Just this last week, a group of travelling Baptists set up camp immediately adjacent to our site, parking their wagons directly next to the road where their hand-painted signs proclaim, JESUS SAVES, warning all who pass by that it is time to REPENT!, and warning, too, BEWARE OF THE DEMON RUM.

Dr. Rutherford, who was raised in a strict Baptist family and is given to strong beliefs of his own no matter what the subject matter, has been in a real lather over their presence, claiming it was the Baptists who stole his childhood and, more importantly, his formative adolescence, with their anti-smoking, anti-drinking, anti-dancing, anti-card-playing, and anti-everything-fun approach to life.

He is right, of course. Children do suffer mightily at the hands of their parents, who too often refuse their offspring an opportunity to find their own meaning in life and, instead, indoctrinate them at an early age. I bless you both for not imposing any organized religion on my life, leaving me to find my own way. I am finding that path here, as the world and all its glories open before me. The natural world is my religion. I worship the random and wondrous beauty of it all.

With such a belief system I should be grateful that Dr. Rutherford has strictly forbidden the Baptists to venture, much less proselytize, anywhere near our camp, a mandate to which they have no choice but to reluctantly agree. But even if the Baptists are limited to preaching the ugliness of hell, damnation, and demon rum outside of our encampment, even Dr. Rutherford cannot stop the sweet sounds of their hymns from reaching us through the trees at night. They are not unlike lullabies, and I have learned to relish the melodies as I drift off to sleep. We all need to find joy and meaning in the world. Even the Baptists.

Our location above the hotel also allows for an ideal separation of labor, with Professor Merriam, one of the students, and I systematically collecting off the road along nearby creekbeds and meadows, while Dr. Rutherford, the other student (whomever is lucky enough to “win the toss” for the day), and the expedition driver and his dog, travel the main wagon roads in their search for specimens.

Dr. Rutherford, as I may have told you, has come late to science, being a farmer by birth and inclination, and yet he has developed an admirable collecting technique, one which I would like to incorporate into my own field work at the earliest opportunity. When Professor Merriam first proposed this expedition, he invited a cartographer to help document our collecting. Said cartographer ran off and got married instead, but he did provide the Professor with a detailed elevation map first charted by Hayden and the government surveyors. This map of Yellowstone National Park has served as a guide of sorts for Professor Merriam as he has planned his work, but it is Dr. Rutherford who has made the best—or at the least most scientific—use of it.

As I may have mentioned when I first arrived, Dr. Rutherford spent his first month here nursing the camp’s fire. But he also, it turns out, spent at least some of his time, he claims out of boredom, copying to scale large sections of the Hayden map. To this grid he added known thermal features, mountain passes, major roadways, &c. At the time, this seemed a harmless diversion but he has now taken to riding with the mountain man driver on these major thoroughfares, collecting specimens, and adding them specimen by specimen to his grid, along with dates and time of day coupled with detailed weather information.

He and his assistants make quite the sight. After a late breakfast, the threesome pack their day’s supplies, including a large jug of brandy or some other foul-smelling alcohol, and head off down the road. They travel in their wagon at a leisurely pace, the buckskinned driver dozing off as the horse moseys along the roadway, the student, following behind on foot, gathering samples from the areas alongside the road and the adjacent hillsides at Dr. Rutherford’s command.

Dr. Rutherford, in the meantime, issues his royal mandates from the back of the wagon which he has converted into a virtual throne, complete with tarp canopy. It is while seated thus that he logs the student’s findings and plots each specimen collected on his hand-made maps.

Down the road they proceed, the driver snuffling in his sleep, Stony or Rocky scurrying here and there, the driver’s dog barking at their heels, and Dr. Rutherford scanning the roadsides like they were indeed his private reserve. They proceed until they reach a hot pool or stream at which point they have an agreed upon arrangement that they will stop for refreshments and, if water temperature allows, partake in a long, hot soak. Depending on the direction they head out, and the number of specimens and thermal features they encounter along the way, the three return to camp quite pickled from the day-long combination of hot water and lukewarm liquor. You can understand why such an assignment would be an agreeable one to a young college student, and why said assignment is hotly contested each morning by the flip of a coin.

As you can also imagine, it is a situation destined to drive Professor Merriam to distraction. Just the other day, Dr. Rutherford and his coterie pulled into camp after dark, the horse being smart enough or at least hungry enough to find its way home without the benefit of human guidance, since all three were sleeping soundly in the wagon. I would have laughed right out loud to see them in such a state, if Dr. Aber from the Smithsonian had not been visiting camp at that particular moment. His presence made the sight of the drunken crew even worse for the Professor who was clearly not amused by Dr. Rutherford dozing on his throne, the student curled peacefully at his feet, and the driver, stretched out in front of the wagon across his own royal seat, his hair and beard and skins dangling every which way as the horse trotted into camp. Even the dog was asleep. All four snored so loudly that they drowned out the Baptists’ joyous hallelujahs which drifted into our camp through the trees.

And yet, in spite of all the grief Dr. Rutherford causes him, even Professor Merriam must begrudgingly acknowledge that Dr. Rutherford’s collecting technique is producing quality results, with his elaborate system of mapping leading to some engaging evening discussions and scientific speculations about plant variety and distributions. Why is it, for example, that Coulter identifies Pentstemon caeruleus as a plant of the plains of Dakota, and yet Dr. Rutherford has clearly mapped clusters of the species growing alongside the mountain roads he travels? Could it be that the act of road building creates new and welcoming conditions for the spread of these plants? Or perhaps those who visit the Park carry the seeds like wayward birds, depositing them at random as they travel along the roads.

These are the kinds of questions Dr. Rutherford’s maps raise, as they provide us with a broader perspective of the Park than any of us could individually obtain in the field. I hesitate to make the allusion, but it is as if Dr. Rutherford’s maps illustrate the Park’s flora in concert, as opposed to simply logging in each individual note.

Dr. Rutherford has also been the first to collect and identify specimens of Castilleja miniata, which Professor Merriam refers to as “Indian paintbrush.” This is not the same species of plant I have heard referred to as Indian paintbrush in the Northeast, nor is there any mention I can find of an Indian paintbrush in Coulter. When I told the Professor as much, we proceeded to have an animated conversation (notice I avoid the word argument) about the obvious limitations of common names.

But conversing as eloquently as I could, I was unable to persuade Professor Merriam, who steadfastly believes that nonscien tific names portray the “genius of the people.” According to him, names like Indian potato, bitterroot, fireweed, golden eye, and death camas describe how plants are used, consumed, or propagated, how they look, or, in his exact words, “are to be avoided because of their unfortunate habit of lying in wait for some unsuspecting herbivore—man or beast.” It is through embracing these names, the Professor maintains, that scientists can develop and encourage botanical awareness in amateurs and, through such awareness, enlist their help in protecting and preserving our natural history and national treasures like Yellowstone National Park.

This engaging discussion has continued sporadically on our own outings into the field, since the three of us (the Professor, the student whose luck fails him in the coin toss, and I) have been recently joined by a Crow Indian and his family. How this particular Indian came to join our camp may be of particular interest to you, Father, for you are right as always: the government is indeed forcing these people off the land and away from their traditional sources of food and livelihood.

From what I understand, it happened something like this. A woman traveller, accompanying a coupon tour viewing backcountry geysers, had wandered into the woods where she was momentarily separated from her party. She was never at risk, but she was disoriented enough so that she began to worry and probably even fear for her safety. Hearing someone approach on horseback, she was greatly relieved and hurried with much abandon toward her supposed rescuer, only to discover that said rescuer was none other than the Crow Indian. The Indian, it turns out, was hurrying himself, trying to avoid contact with the woman’s party, who were waiting in a wagon parked on the road directly below them. Having missed their companion, they were calling out for their missing member.

Upon seeing the Indian, the woman automatically assumed that she was about to be attacked or worse and, thus, spontaneously regained her sense of direction and ran frantically down the hill, out of the woods, and onto the wagon road screaming for help. The Indian, no doubt as terrified as the woman, galloped silently away in the opposite direction. The woman and her friends hurried back to the military headquarters in Mammoth, hysterically informing each and every traveller they encountered along the way about the Indian war party which had invaded the Park.

Now I have met Capt. Craighead from cavalry headquarters on a number of occasions, and can vouch for his good nature and sensibility, but what could he do but head out and search for the so-called warring party? If he did not act, he would have soon had a warring band of vigilante tourists on his hands. There exists a strong sense of rightful ownership of our Nation’s Park, and those claims do not include the Indians.

Two days later, Capt. Craighead and his men did indeed discover a meagre Indian encampment, consisting of a tipi and campfire high on the ridge above Mammoth Hot Springs where the young Indian, his wife, and two small children were living. The family apparently entered the Park through the northeast, in search of obsidian, a volcanic glass which is still used by natives for making traditional tools and knives and is in abundance here. By entering through the back door as it were, the family had evaded the cavalry and other Park authorities who probably would have otherwise denied them entrance. The family could have easily spent months undetected if the Indian had not had the misfortune of unexpectedly running into the lost female traveller.

As I may have mentioned to you before, Professor Merriam taught for two or three years while botanizing on the Crow Indian reservation. Knowing this, Capt. Craighead called upon the Professor to translate for the Indian who speaks little English, in spite of having received a full “Christian” education at the Unitarian mission on the reservation. From what I have since learned from Professor Merriam, it was the captain’s goal to prosecute or, at minimum, expel the young man and his family from the Park since they discovered a small bundle of obsidian in his possession. But as the Professor explained, although it is illegal to remove any physical feature from the Park, and there are no exceptions, the obsidian found with the Indian was still inside the Park and, thus, technically not illegal for him to have in his possession. Besides, the Indian insisted this was his own personal obsidian, which he had carried with him into the Park, but this would have been more difficult to prove.

To make the story even more interesting, Montana is so much like a small town that Professor Merriam knew the Indian’s father, a tribal leader, who had assisted the Professor in his early botanizing on the reservation. Like his father, the son, with the curiously Americanized name of Joseph Not-afraid, is extremely knowledgeable about native plants and their traditional uses, so Professor Merriam has vouched for the young man, and has enlisted the Indian’s help in identifying the specimens we collect. Capt. Craighead, to his credit, has agreed to this arrangement, claiming to be dedicated to the expedition’s success.

So now Joseph accompanies us on our day-long ventures into the backcountry, with his wife, Sara, and their two small children, one of whom the woman still carries on her back. You can imagine the reaction as wagons of travellers pass us on the road. Most are thrilled at the opportunity to see real, live “Injuns,” but a few, perhaps having heard of the alleged warring party which had invaded the Park, have complained to authorities. I must say that I now have nothing but respect for Capt. Craighead, who has proven to be firm in his support of Professor Merriam and his work. I only wish I could say I had similar respect for the medical botany and common names that Professor Merriam appears to be championing with this Indian.

Still, their work together has created a unique opportunity of sorts for me and my own studies. While Professor Merriam and Joseph discuss at length (and often at great difficulty given the language differences) the nutritional or medical or spiritual properties of a particular plant, I have time to illustrate flora in its natural environment. I am finding this particular task to be one of the greatest learning experiences of the time I have spent here so far. I am beginning to look at which plants grow in relation to others and in what kind of physical setting. I am also keenly interested in the different conditions under which they are growing and the dates they are in flower at different elevations.

It is clear to me now that if I could adequately document just one area of the Nation’s Park throughout an entire season, I would be a long way toward understanding the development of plant life and all of its complexity. I may enlist Dr. Rutherford’s novel approach to documenting our collection to help with such a project.

Unfortunately, my expanding interests and the non-scientific botanical pursuits of the Professor and his Indian friend have done little to win the confidence of the expedition’s supporter, Dr. Philip Aber. He is a fine scientist and extremely intelligent and well read, but very much a traditionalist when it comes to what—and whom—should be considered “scientific.” I still wonder at his apparent acceptance of me. Perhaps he has yet to notice that I am a woman. Maybe he is more interested in the fact that I am a Bartram. In either case, I can tell he is not impressed with my new work, referring to my illustrations as “group portraits.” And he only speaks of Professor Merriam with contempt. Even to his face.

Sadly, Dr. Aber appears to be under some sort of personal stress, since his wife and family have yet to join him here as planned. I can only hope that his displeasure with life in general does not affect his support of the Professor and our work. While I sympathize with Dr. Aber’s lack of appreciation for the Professor’s interests, I believe I am making much progress, and would hate to have that interrupted.

To give you an idea of how well I am doing, I received a letter from Lester complimenting me on the quality and overall condition of my Yellowstone Park collection, if you can believe it. He thinks I may even have discovered a new genus. He is sending a sample to a contact he has at Harvard to be sure. If he is right, it could be my first genus Bartramii to match the B. family of mosses!

Lest you think it is all work and no play, tomorrow is the summer solstice and Dr. Rutherford and friends have planned a “summer festival,” complete with music, song, and recitations to celebrate the longest day of the year. It will be our turn to blast out the Baptists with our own pagan hymns. And this is just a prelude to a long weekend of fun planned at the hotel for the 4th of July.

I will be thinking fondly of you both during the festivities, as I think of you daily, and as I hope you are thinking of me.

All my love,

Alexandria

Philip Aber

Lake Hotel

Yellowstone Park, Wyo.

June 20, 1898

William Gleick

Smithsonian Institution

Washington, District of Columbia

Dear Bill,

I write to you as a friend, for a friend I hope you are, since there is no one else to whom I can confide my situation. I am embarrassed to report that I have found myself in a bit of a personal and professional difficulty with which I am hoping you can assist.

I have had the opportunity to spend a considerable time with your colleagues in the Park and now fully understand why you chose to journey on your own to the capital rather than to venture here with your friends. Merriam has opted to ignore the ample luxuries of the Park hotels, and has instead set up a camp of operations near the Lake Hotel. He and his assistants live in the most primitive of conditions, eating poorly cured beef and game, and generally risking their health and wellbeing—not to mention my significant investment—in the name of economy, for it certainly is not in the name of science. The camp, with its worn out tents, ramshackle tables, and make-shift equipment, might be barely tolerable for a weekend camping holiday for college boys, but it is certainly not conducive to serious research.

Instead of establishing himself in some respectable fashion, and hiring underlings to venture into the field on his behalf, the underlings often stay in camp, sleeping all hours of the day, I might add, while Merriam sets off each morning with only Miss Bartram, a student, and some Indian he has picked up along the way to assist him. It is bad enough that this strange entourage brings discredit upon Merriam, who seems oblivious to the fact that he has become yet another of the Park’s wonders—tourists go out of their way to view the party as it makes its way on foot along the wagon roads. But I will not tolerate the fact that such a spectacle casts aspersions on my own reputation, for supporting such canaille. And that is not to mention the questions Merriam’s lack of respectability raises about the integrity of the Smithsonian Institution itself.

Worse yet, while still at Mammoth, Merriam left camp in a pouring rain to explore some remote location with only Miss Bartram to assist him. I am very open minded when it comes to science, but this is hardly a decorous situation, much less a sensible one, and was ripe for a serious mishap. Which is exactly what happened. After foolishly putting himself and Miss Bartram in unnecessary danger, Merriam apparently lost his way and, when searching for the proper path to return them safely, proceeded to fall off a cliff. It was only through the dedication of an off-duty cavalryman and some Montana cowboy, who located Merriam and brought him back to camp, that the fool managed to survive at all. As it is, Merriam now limps noticeably and carries his arm around in a sling. Not much science will result under his feeble leadership, that is clear.

Which brings me to my difficulty. I have made arrangements for my wife and family to join me here at the Yellowstone Lake Hotel. Would you call upon her and assist her in whatever way possible to ensure that she has the strength and commitment to make the journey? She is not in the best of health, with two small children to care for but, as you can imagine, I must stay here, at minimum, for the month that I had planned to ensure the expedition’s success. To leave now would doom the entire enterprise, and could possibly put my own fledgling career at the Smithsonian at risk.

Thus, my dilemma. I admit to you in all honesty that I cannot face a summer apart from my family, particularly under these conditions. If you would call upon my wife on my behalf, discreetly as you must understand, it would be a great service indeed. And please, do not trouble my wife with these details. Just ensure her that she will thoroughly enjoy the accommodations of the hotels and the other wonders here in the Park.

I hope your studies are proceeding as planned and that you are not discovering your own personal or professional difficulties while in our Nation’s Capital. However, should you ever encounter any problems at all while in the District or while working at the Smithsonian I hope you will feel free to call upon me as I have, without any sense of pride whatsoever, felt free to call upon you.

Yours sincerely and most faithfully,

Philip Aber

Howard Merriam

c/o Yellowstone Lake Hotel

Yellowstone National Park

June 22, 1898

William Gleick

Smithsonian Institution

Washington, D.C.

Bill:

I am writing again to try my utmost to convince you to join us here in the Park at your earliest convenience. As you can well imagine, with such a small group of men, I can use the help in the field now that it is warming. More importantly, it is the time spent outside of the field where I am at a real loss, particularly as I try to deal with my benefactor, Philip Aber. For some reason, Aber has become convinced that I am most unsuited to manage this enterprise, and so has taken to supervising and instructing me and my activities as closely as he might his youngest child. I feel like I am under the microscope here, and it detracts mightily from my work.

And work, at last, I am doing. Thanks to the excellent care provided by the medical staff at the cavalry hospital in Mammoth and, I am told, thanks to the preliminary measures taken by Miss Bartram, my arm is healing and I am more mobile than anyone would have the right to expect given the fall I took. So I am back in the field again, busily gathering samples and doing my utmost to develop in-depth knowledge of the flora in these lower elevations.

I have, by chance, encountered a native from the Crow Indian reservation who has much knowledge about traditional plant names and uses and I am taking advantage of his brief stay in the Park to learn as much as I can about plants considered useful or poisonous. It is critical that information concerning the properties of these native plants be collected now from those who have for generations needed to rely on them for food, medicine, and other purposes, since these people are being weaned from their traditional way of life and, as a result, generations of tribal knowledge will not last long. Sadly, it is not only their knowledge that is at risk. They have been herded like animals onto reserves, and I fear it is only a matter of time before they disappear from the human scene altogether.

I can tell Miss Bartram does not appreciate my interest in preserving this information, since she is very traditional in her approach to science. Except for an occasional spirited discussion, however, she leaves me to my studies as long as I leave her to hers. Rocky and Stony, the two students who are accompanying us, have also been remarkably cooperative, given the long hours and number of miles we cover each day, and have demonstrated a curiosity if not an interest in our work.

So, surprisingly, has Rutherford, who has reluctantly but dependably followed instructions and returned to camp each night with more specimens than I could have ever hoped for, even if he does follow Miss Bartram’s wasteful example of preserving only one specimen per sheet. Miss Bartram, understanding the financial limitations of the expedition, has been gracious enough to furnish her own specimen sheets which are mailed to her along with other supplies from New York. Rutherford, on the other hand, dips daily into my own personal supply as he catalogues and preserves the expedition’s collection. His is an extravagance we cannot afford and I have told him so.

But these minor financial worries pale when compared to the people problems I am encountering. This is work for which I have no training or natural inclination, and one which I would just as soon ignore as long as the overall goals of the expedition are being met. Aber, on the other hand, is obsessed by his need to control the every breathing moment of the expedition and insists on visiting our camp at the most inopportune times, allegedly to check on our progress but more likely to catch us with our collective pants down if you know what I mean.

Just the other night, for example, Aber wandered into camp unannounced, only to find every vagabond travelling the Grand Loop, not to mention the young, foot-loose and fancy-free staff employed at the Lake Hotel, settled in for a long spontaneous night of music and merriment in celebration of the Summer Solstice. Aber was no doubt attracted by our campfire which had grown from a few logs fed hourly, to a bonfire large enough to burn down the entire encampment given even the slightest breeze.

I assured Aber it was a spontaneous event, Rutherford being too exhausted by day’s end to organize such revelry, but I was not the only one to observe that the participants all seemed to have spontaneously brought food and drink to share (there was much drink including a potent home-brew) and that each of the 50 or so merrymakers (or trouble makers depending on your point of view) had spontaneously prepared a skit, recitation, or song in celebration of summer.

Miss Zwinger, a woman who has taken great interest in our expedition and who regularly calls upon our camp, prepared a dramatic reading of Shelley’s poem “The Sensitive Plant”: “It loves, even like Love, its deep heart is full; it desires what it has not, the beautiful!”—a poem guaranteed to raise more than one set of eyebrows I can assure you. If hers was the limit of provocative presentations, I could have endured it, but there was more. Much more.

Another visitor, an accountant on his way by bicycle through the Park, told, in much detail, of the first discovery of Yellowstone Park. We all had a good laugh at the early reports of a bubbling hell where entire forests were “putrefied,” stories so far fetched that it took years before anyone even bothered to investigate the veracity of them. And yet, who amongst us would have believed the stories if we had not seen this bubbling hell with our own eyes?

Not to be undone, a young woman travelling with Miss Zwinger advanced to the fire with her copy of Chittenden’s book on Yellowstone National Park, from which she proceeded to read a hair-raising tale of massacres and pursuits of renegade Indians in the early days of the Park. Now if the young lady had continued to read to the end of Chittenden’s tale, she would have revealed that even Chittenden was sympathetic to the plight of the Nez Percé who were, in the author’s words, “intelligent, brave, and humane.” He was also wise enough to predict that history would prove that the Indians were in the right. As Chittenden noted, the Nez Percé were making a last, desperate stand against their inevitable destiny, refusing to give up everything, including their land and their dignity, both of which had been theirs for centuries before the arrival of the paleface.

But the truth is often the last ingredient of a good story and all seemed happy with the general effect of the young lady’s abbreviated tale. All, that is, except for Philip Aber.

When the next performance turned out to be a rousing rendition of “Turkey in the Straw” on a fiddle and guitar, Aber took me aside and asked if it was prudent to invite Indians into our camp given their history in the region.

Different Indians, I assured him, and different times. The run-in with the Nez Percé had taken place twenty years before. But Aber was not appeased.

“You have women here to look after, and our reputation,” he added, the anger rising in his face and voice. “You can’t have Indians lurking around in the trees.”

“But they are helping with my field studies,” I replied, anxious to defend myself and my own reputation. “The young man is incredibly knowledgeable about the plant life in this region.”

“Knowledgeable?” he shouted back at me. “Knowledgeable? An Indian is more knowledgeable than you are? What are you telling me, man? That I would be better off hiring a savage to do the work I’ve hired you and your friends to do?”

Fortunately, by this time the lone fiddle and guitar had been joined by a small band of instruments played by the boys from the hotel, supplemented by a foot-tapping and hand-clapping tempo led by Rutherford beating a wooden spoon and a ladle on one of the cook’s large stew kettles. The resulting noise (I am hard-pressed to describe it as music) drowned out our argument so the party-goers were oblivious to our confrontation. Still, I felt embarrassed that not only my credibility but my ability to lead a scientific expedition had come under attack. And by someone who has not a clue how to collect specimens in the field, preferring the comforts and daily luxuries of the hotel. I fought back. What else could I do?

“Who are you to tell me who I can or cannot have helping me?” I shouted over the clamor. “You who sit in your hotel room all day, never even venturing into the field? You have no right to tell me how to do my work, and with whom. You have no right.” And then to be sure he understood my point of view, I added, “You have not earned it.”

If the music had not ended at that exact moment, I am quite certain our exchange of insults would have escalated into an exchange of blows. As it was, the merriment subsided to much hand clapping, hoots and whistles, after which the noise quieted long enough for another performer to step forward into the light of the fire.

“Who is next, who is next?” Rutherford called out, banging on his so-called drum. “Step forward, and let the celebration continue.”

Aber retreated to the edge of the merrymakers’ circle, where he was almost hidden by the trees. My insults were bad enough but, in retrospect, it would have been much better if I had hit him and sent him packing. Maybe then he would not have witnessed what followed.

“Next,” Rutherford shouted again, beating out a parody of a drum roll on his kettle.

Out of the darkness, our horseman and driver, Jake Packard, emerged. Packard is not the most social of creatures, preferring to keep his distance from the lot of us, although he has taken a liking to Rutherford and his regular liquor shipments, which he had obviously been sampling throughout the day. He held a book tightly to his chest as if it alone were providing the sense of balance he needed as he staggered toward the fire. His dog sat and waited at a safe distance.

“I have sumpen to read,” he said, and the circle of revellers clapped and whistled in appreciation. The dog wagged his tail.

“I jus thought you’d wanna know what these little ladies are reading at night,” he added, smiling and weaving and fumbling through the pages.

“Lissen a this,” he mumbled.

Then he proceeded, not very well I might add, to pick out, word by word, the description of the sexual parts of the plant.

“Flowers open when all parts of the plant are mature,” he hesitantly started. “Sumtimes,” he continued, and then he stumbled, “the and-roe-eek-cum, or sumpen like that,” he did the best he could with the terminology, tripping over each letter in attempt to make it sound official, but we knew what he meant, “matures earlier than the cum-and-roe-cee-um,” he stuttered and spit, “soes not to inner fear with the pollen and pissels of the same flower.”

He looked up and smiled.

“A pissel. I have one of them,” he interjected proudly. Then he spit again into the fire.

The driver drunkenly tripped over the scientific descriptions, but the overall meaning was not lost on the crowd, which stared collectively into the fire rather than look at the matted mass of hair and shabby buckskins that wove back and forth and blasphemed in front of them. He then went on to read in much the same way how the tip of the pollen tube pushes its way into the ovule in the ovary where it makes contact with the female. Cells rupture, the sperm is released, and it merges with the egg. Standard textbook fare. Certainly nothing unusual about it.

“Well,” the driver said hacking and spitting with great ceremony into the fire. “I jus wannad to share that with you.”

The driver waved the book at those sitting around the circle. The dog stood and wagged his tail.

“I offen wonnered what she was doin in there in bed with a book.” He laughed suggestively. “She calls it science.” He spit again. “I call it inneresing.”

Before the driver could continue, Rutherford was beating again on his make-shift drum calling for music, more music. The boys from the hotel jumped at the chance to perform their number, a western campfire song about the trees and breeze and the whispering pines. The driver stumbled back to where he came from, his dog following closely behind.

I looked around for Miss Bartram but could not find her anywhere. She tends to avoid these kinds of social activities, so I can only hope that she had already retired for the night, without her book, and that she had missed the entire dreadful presentation.

I wish I could say the same for Aber. He was still lurking around the circle of revellers, his worst suspicions about my leadership skills and judge of character now fully confirmed. He flashed a look of pure hatred in my direction and then he, too, disappeared into the night.

So, Bill, what should I do? I can forbid the use of alcohol in the camp, and will, of course, do that. But I also know that Rutherford and his friends will simply limit their consumption to when they are either on the road (most of the daylight hours) or visiting the hotel (which would probably be most of the rest of the time if they are not allowed to drink here). They will probably also drink in greater abandon, knowing they will have to make it through the night once they are back in camp.

Another option is to fire Packard, but if he goes, all of our provisions, including bedding, tents, and cooking capabilities, will go back to Butte with him. Then what would I do?

I can disassociate myself from the Indians, but there is no guarantee that will appease Aber at this point, and it might even put the young Indian family at risk. There are some strange people lurking around these parts, many of whom make the likes of Jake Packard look tame.

As you can see, it is the human dilemmas, not the field work or science, which puts me at a real disadvantage here. People are not my strength. If you could join us, even temporarily, I feel that a level of respectability would be restored to our group. You met Aber in the Capital. He speaks highly of you and your abilities. I think in cases like these, your age and stature would be a real benefit, providing Aber with a sense of confidence that he clearly lacks when dealing with me. If you simply wanted to visit the Park and not even worry about the field work, your presence and authority alone, I am convinced, could make a real difference.

Aber originally planned to leave the Park at the end of the month but is now talking as if he is here until the first snow falls. If he knew you were planning on joining us, perhaps that would give him the confidence he needs to change his mind and go home.

So please, please consider my offer. I have no one else to turn to and need your help all the more because of it.

Yours most sincerely,

Howard

Andrew Rutherford, Ph.D.

c/o Lake Hotel

Yellowstone National Park

Temp. 65°F., 0 precip.

June 23, 1898

Robert Healey

President

The Agricultural College

of the State of Montana

Bozeman, Mont.

My dear President,

Happy to report Merriam’s research career fast coming to close. Has alienated Philip Aber, who threatens to withdraw Smithsonian funding. Ruckus & near fistfight over Indians camped in clearing & reproduction of plants. Merriam will soon have no choice but to re-join ranks of economic botanists & agriculturists. Wish I could say was my doing, but result the same. You owe me that new building as promised.

In other news, railroad active in negotiating lease of land through Park. Planning dams, power generation, large lakes. Much excitement with many swells, black coats, high hats in residence at hotel. Merriam meeting daily to talk about herbarium. Has their attention, in spite of his own dismal situation. You should be here to counter with own ideas. This is big money looking for home. Why not build them one in Bozeman?

Might find you enjoy Yellowstone. No known highwaymen. Not known as Wonderland for nothing.

Send supplies care of hotel. Would like anemometer. Windy here.

Yours reliably &c,

Andrew Rutherford, Ph.D.

A. E. Bartram

c/o Yellowstone Lake Hotel

Yellowstone National Park

June 25, 1898

Jess:

I have taken your advice and written a long, chatty letter to my parents. There is no reason for them to worry so, and certainly no reason for them to be bothering you with their worries. Still, I will try my utmost to keep them better informed.

I will not bore you with my day-to-day activities, which have settled into a gentle routine. But now that we have moved to the lake and the “season” is upon us, I have had some interesting backcountry encounters and experiences which illustrate how far I have come on my journey—or how far I have fallen behind, depending upon your point of view.

First, I should point out, as I should have made clear to my parents, that Professor Merriam plans each day’s outing to the minute to ensure that we are always back in camp before the first signs of nightfall. He has become almost obsessive about this, probably because he fears the wrath of Philip Aber from the Smithsonian. He not only sponsors our work, but monitors our activities closely. Should we ever be even a few minutes late, I am quite convinced that Dr. Aber would call the entire U.S. Cavalry out to prove his point that the Professor is not to be trusted.

Professor Merriam’s commitment to being back in camp before dark does limit our destinations since we can, after all, only cover so many miles and still return by the light of day. But knowing exactly where we are headed and when we will return does bring a certainty to each outing which the Professor apparently finds comforting. After spending a night in a spring blizzard, I suppose I should take some comfort from it as well, although I question how we will ever manage to collect alpine species once it warms in the higher backcountry if we are confined to our camp on the lake. But those are the kinds of logistical problems that Professor Merriam must work out on our behalf. As Dr. Rutherford is fond of saying, “The Prof doesn’t pay us to worry about the details. That’s his job.”

The other day, while on one of our well-planned excursions, Professor Merriam was collecting along a streambed with the Indian, who is his constant companion now, while I chose to climb to a shady forested area above and to the right of them. As I pushed through the trees to a clearing on the other side, I came across a small, green tent-like structure sitting just on the edge of the clearing. Curious, I silently crept toward it, not exactly sure what I was looking for, but not at all prepared for what I found.

“Shh,” came a voice from inside the tent.

I stopped, of course, and listened, but I could not see or hear anything other than a slight breeze which rustled through the trees. I continued walking, quietly, toward the tent.

“Shh,” came the voice again, as a twig snapped under my foot. “You will frighten them.”

Again I looked around to see what or whom I might be frightening. I could see nothing. The flap of the tent opened briefly. A hand motioned me forward.

“Hurry,” the voice whispered. “Just be careful,” it admonished.

Silently, I inched toward the diminutive structure, which opened slightly to let me in. Because of the darkness inside the small tent, it was difficult to make out who or what was inhabiting it, but I accepted the welcome and stepped inside.

“Here,” the voice whispered, grabbing my arm and guiding me back toward a narrow camp stool. “Your eyes will adjust in a minute.”

I sat and waited. “Aren’t they beautiful?” the voice whispered again. “A family of yellow wings.”

Slowly, as my eyes adjusted to the darkness, I saw to what the soft, quiet voice referred. In the tree directly across the clearing a Dendroica petechia was feeding her young.

“Here, try these.”

From out of the shadows emerged a pair of opera glasses, which helped to bring the young birds into clear focus. She was right, for the voice was that of a woman, the young warblers with their soft, downy feathers and urgently gaping mouths were indeed humorous if not exactly beautiful to watch.

As my eyes adjusted to the darkness, I could now also see the woman in the tent quite clearly. She smiled and, although she was at least forty, maybe even fifty, she, too, seemed young, birdlike, with tiny, wide-set eyes which darted with pleasure as I handed back the glasses. She held them in her lap and shrugged, her small head dipping into her shoulders, her eyes crinkling.

“Isn’t this wonderful?” she whispered.

I looked around the small, homemade bird blind, for that was what we were sitting in, and understood that once, and not so long ago, I would have imagined such a stuffy, restricting place anything but wonderful. But now, that afternoon, it was exactly that. Wonderful.

“My name is Mrs. Eversman,” she whispered, briefly offering me her hand. “Or, I should say, Mary Anne. I am here from New York to be a watcher in the woods. What brings you to Yellowstone?”

I whispered a few words about my work in the Park, and she seemed delighted, her hands fluttering lightly in the pool of her skirts.

“Oh, a scientist,” she sighed, now clasping her hands as if to quiet them. “How I do admire you. I have always wanted to be a scientist, but,” she added with an apologetic dip of her head, “I’m really just a dabbler. What you might refer to as a nature lover, I suppose. And now, ever since my husband died, I guess I’m also a bit of an adventuress,” she confided.

She stopped as if to think what to say next, her opera glasses again scanning the trees. Taking note of the mother bird’s flight, she checked a small timepiece which hung from a gold chain around her neck. She then made a notation in her journal.

“If I were a real scientist,” she said, closing the book and placing the glasses atop it, “I’ve been told that I would stay home and pay more attention to that which is around me. Instead, I prefer to travel. Looking,” she added, and motioned with her quick, birdlike hand around the expanse outside her small enclosure. As she did so, a bird in flight caught her eye.

“Ah, there,” she whispered, handing me the glasses again. “In the tree, to your left. Do you see him? A mountain bluebird.”

There was indeed a bright blue bird, the likes of which I had never seen. Small, almost iridescent against the green, it rested for only a moment and then was gone.

“I guess I’m too restless for real science,” she said, leaning towards me to once again retrieve the glasses. She smiled, her eyes brightening at just the thought of her quest.

She was certainly not dressed for the scientific life, nor for ad venturing for that matter. Compared to me, with my now ragged and filthy field clothes, she looked positively radiant, with her suit of pale blue serge, not unlike the color of a bird’s egg in spring. Her shirtwaist was starched and prim, her thick brown hair, softened by threads of grey, neatly pinned. Another smile crinkled her face, her head dipped into her shoulders, and she returned her gaze to the trees.

“What a wonderful world this is,” she said quietly.

I would have enjoyed sitting there all day with Mrs. Eversman, but I could now hear Professor Merriam calling me from down the hill. Since our near tragedy in the snow, I have come to understand that I really must be more responsible and responsive to the needs of my entire party. And from the Professor’s perspective, right or wrong, that means knowing where I am at all times. It is not the kind of arrangement to which I would normally agree, but Professor Merriam is still so clearly uncomfortable with my presence here that I need to do all that I can to make him think of me as an asset, as opposed to a constant liability.

I could hear the Professor and now the student, too, calling again, closer this time, so I started to take my leave, regretting my departure from Mrs. Eversman and the tight confines of her blind, but fearing that their calls would disturb the birds. I felt uncomfortable, too, abandoning her there, all alone, in the woods. So, in leaving, I offered to help Mrs. Eversman back to the hotel with her things when my party and I headed back down the trail later in the afternoon.

“Oh, no,” she said without hesitation. “I never go back to the hotel before nightfall. I love that hour or two before dark. The woods come alive, the birds settle, the weather calms. I never miss it.”

Again the crinkle of the eyes, the small, almost apologetic dip of her head to one side, the smile. And then the opera glasses scanning the trees as I crept from the blind.

Funny, the notion people have of science. I can think of nothing more tedious than sitting for literally all hours of the day in a stuffy, dark bird blind not much bigger than a wide-brimmed hat covered with a heavy piece of canvas. And yet, there that woman sits, day in and day out, fighting off flies, mosquitoes, and the stifling heat of day, meticulously observing and documenting the nesting habits and life cycles of birds. If that is not science, I do not know what is.

I have since learned from Miss Zwinger that Mrs. Eversman has led a national campaign amongst amateur birdwatchers like herself to replace the use of shotguns with opera glasses, and to discourage the growing popularity of collecting bird eggs and nests. She has even waged war against the use of feathers in hats and has travelled extensively on behalf of her cause. This is, no doubt, from where the “nature lover” classification has come. Scientists who write for professional publication, and who prefer to tramp through the fields with guns, can be extremely cold-hearted toward those who do not pursue their own brand of science. Particularly old women who sit alone in the woods with opera glasses for hours on end.

I, for one, can certainly sympathize with Mrs. Eversman’s perspective. A dead bird, no matter how beautiful and informative it appears neatly laid to rest in a drawer, is still nothing more than a stuffed museum specimen. To understand the true nature and classification of birds, you must, like Mrs. Eversman herself is doing, spend hours on end observing the living, breathing—and I might add messy and unpredictable—creatures in the field. That, at least to my mind, is real science, no matter what the other so-called scientists say.

Jessie, I know I am sounding quite didactic, but there is so much bad science or non-science wrapped in the guise of science that I cannot tell you how refreshing it is to meet this watcher in the woods. She may be sentimental about her subject, but she relies entirely on patient observation for her understanding. We need more of these so-called nature lovers in the world.

But I digress.

As I hurried around Mrs. Eversman’s clearing, careful not to disturb her birds, and down the hill toward the creekbed where I could still hear the Professor searching for me, I saw John Wylloe, another of my new Park acquaintances if you can believe it, heading up the trail a half a mile or so below me. He waved, having seen me, too, and hurried up the path in my direction.

Mr. Wylloe is the writer my mother most admires, much to my father’s scientific and literary consternation. I think my mother has read every book John Wylloe has ever written, both his nature essays and his poetry. He was kind enough to share a few of his volumes when I first arrived in the Park, but I must admit I find his work too sweet for my palate. However, considering all the inferior so-called nature writing—and I use the term lightly—in the world today, at least Mr. Wylloe’s is based upon sound observation of the natural world. In fact, he has used his name and reputation to effectively argue against this ubiquitous kind of writing which makes for entertaining and humorous reading but is not, contrary to the authors’ insistences, based on the real world. As Mr. Wylloe passionately argues (and I assume Mrs. Eversman would agree), song birds do not conduct singing schools in the woods for their young, nor do they set their broken legs with mud casts bound with grass, twigs, and horse hair. I do not care one fig for what has been “documented” in the likes of Harper’s and Forest and Stream.

It is against such nonsense and the magazines that publish it that Mr. Wylloe rigorously campaigns. In fact, he has publicly taken to task George Bird Grinnell, the editor of Forest and Stream, arguing, quite rightly I might add, that a man in his position should know better than to print such foolishness. Mr. Grinnell considers himself a hunter naturalist, an oxymoron if ever I heard one. He is also one of the founders of the Boone and Crockett Club and established the Audubon Society, both dedicated in their way to an appreciation and preservation of the natural world. Surely these organizations cannot possibly believe that you can only appreciate and preserve that which is somehow human. That is like the Baptists maintaining that true believers can only celebrate that in which they see God.

But I must give Mr. Grinnell credit. He is wily when it comes to Wylloe. In his editorial wisdom, Mr. Grinnell has hired Mr. Wylloe to contribute to Forest and Stream, and is sponsoring his summer-long stay in the Park. Mr. Wylloe claims not to need the money, apparently even nature writing based on science is a lucrative profession these days, but he has taken the assignment, he says, to demonstrate to Mr. Grinnell and the rest of the popular press that the truth of the natural world, in all its interesting and unpredictable diversity, can be as entertaining as that which is based on some urban writer’s imagination. What a stroke of editorial genius to send him, then, to Yellowstone National Park where the scientific “truth” is as far-fetched and fiction-like as anything the average reader would encounter anywhere in the world! I am curious indeed to learn how Mr. Wylloe will handle his dispatches.

As Mr. Wylloe advanced up the path, slower now as he appeared short of breath, Professor Merriam emerged from the creekbed, again calling out my name. He saw me now and waved, but when he saw John Wylloe, he hesitated.

“When you have a chance,” he said abruptly, and retreated into the narrow ravine.

Since Professor Merriam could rest easy knowing of my location, I waited for Mr. Wylloe to ascend the final few feet to where I stood. He was visibly out of breath, struggling as he advanced. Dressed as he was, you would need a good deal of that urban writer’s imagination to see him as the Nation’s leading naturalist and outdoors-man. With his long white hair and beard, black suit, wide-brimmed hat, and fishing creel, he looked more like an ancient scribe, perhaps someone from the Bible assigned to carry bad news, or one who has travelled for miles to worship at some holy shrine.

“Forgive me, Miss Bartram,” he said, clearly out of breath, “but I find I still am not conditioned to these higher elevations.”

Balancing himself with his hands on his knees, he lowered his head. Although I hated to see him so distressed, it was reassuring to note that even the greatest minds and talents are limited by the same physical rules of nature as the rest of us. Mr. Wylloe waited thus for a moment or two, his head bowed as if in deep concentration, took two deep breaths which he exhaled as deeply, and then raised his head slowly, like a snake uncoiling its face to the sun.

“Miss Bartram,” he said, offering me his hand in salutation or perhaps to steady himself. In either case, he drew himself closer to me, taking my solitary hand into both of his. He took another deep breath, and sighed.

“I have come here to ask a favor of you,” he said. “One which I hope you will be so kind as to grant me.”

I told him, of course, I would do for him what I could, and he smiled, a thin, weary slit which lifted the corners of his beard for only the briefest of moments.

“I would like to accompany you, if you will have me, on your outings into the field.”

I was quite taken aback, not that he would ask, for I know of his general interest in science and natural history, but that he would ask me, rather than directing his question to Professor Merriam. I was certainly not in the position to grant his favor, and I told him so.

“The Professor decides who should . . . ,” I started, but Mr. Wylloe interrupted me, as impatient as he was out of breath.

“It was Professor Merriam who referred me. You see, it is you—or I should say your work—that I am interested in and, thus, it is you and your work I would inconvenience if such an arrangement were not to your liking. Therefore, the Professor referred me to you directly.”

I admit, I was puzzled by the request. Flattered, of course—all I could think of was wait until I tell Mother!—but it did seem a bit of an inconvenience for all concerned. And yet, how could I refuse him his offer? He was, after all, John Wylloe.

I told him he would be welcome to join our daily expeditions at his convenience. However, I warned him, he must keep Professor Merriam informed of his desire to join us on any particular outing. It would be presumptuous for Mr. Wylloe to inform me of his intentions in this regard. It would place me in an awkward position within my group.

Mr. Wylloe thanked me, still holding my hand warmly between his own, at which point I excused myself, reminding him that the Professor had asked that I join him.

“Well, then, if it is not inconvenient,” Mr. Wylloe smiled, releasing me, “I will accompany you, and we shall inform Professor Merriam of your decision together.”

This, too, seemed inappropriate but I did not object. Rather, I led Mr. Wylloe down a thickly shaded path until we reached the creek. Professor Merriam looked up at our approach, but said nothing.

“She said yes,” Mr. Wylloe called out, at which the Professor nodded slightly in acknowledgment, before returning his attention to the Indian.

As I advanced down the trail to where Professor Merriam was working, I started to apologize for the delay in responding to his calls, anxious to inform him of my encounter with Mrs. Eversman and her blind, but he, too, cut me short with an abrupt wave of the hand.

“No, that’s not why I called,” he said. “Here, I want you to see this.”

He then led me to a solitary pink blossom, growing next to the stream.

“Do you know what it is?” he asked.

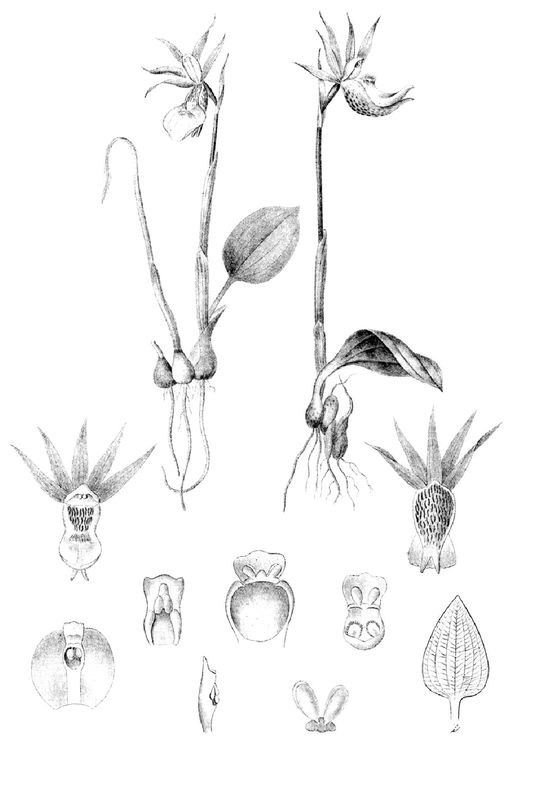

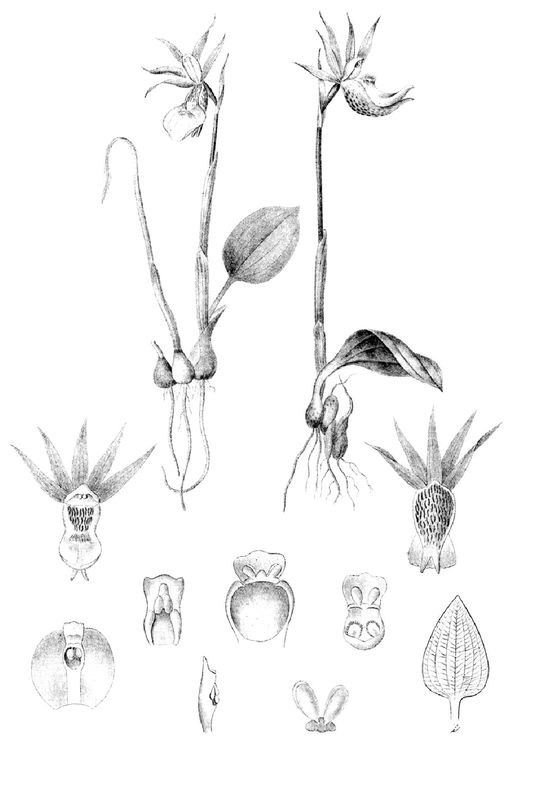

I had to admit, even after close inspection under my hand lens, I could not name it. Located as it was next to a stream, with three sepals and three petals, a member of Orchidaceae was the best that I could do for certain.

“Joseph has asked me not to remove it,” Professor Merriam informed me.

I must have looked at him very strangely because he hastily continued.

“It is alone,” the Professor explained. “And since it cannot be named, Joseph is convinced that it must be sacred.”

Professor Merriam watched me closely for my reaction. Of course, that was the most ridiculous thing I had ever heard, and I told him so.

“You cannot name it if you do not take it,” I reminded him. “Besides, what about the collection?”

As Professor Merriam and I talked, John Wylloe removed his boots and socks with great ceremony, rolled his pant legs to just below the knees, and sat gingerly upon a large rock, slowly easing his feet into the icy creek. Even from where I was standing, I could see them lying low in the water like two albino Salvelinus. He took off his hat and, again, unfurled his spine, vertebrae by vertebrae, so that his face was fully oriented toward the sun, his long white hair and beard almost translucent in the fierce light.

As Mr. Wylloe settled in, Professor Merriam conferred with the Indian in Crow, and then the two of them advanced down the streambed, leaving me, Mr. Wylloe, and the intact orchid without another word. The student looked at me apologetically, and then he, too, followed the other two downstream.

“It is a slipper of Venus,” Mr. Wylloe said to me once the three of them had woven their way out of sight. “Or a fairy slipper. I have heard it called different things associated with footwear on the rare occasions I have seen them near my cabin. But the Indian is right. From my limited experience, they are rare. He may be right, too, about them being sacred, but that is beyond my ken.”

With that short burst of speech behind him, Mr. Wylloe removed his feet from the water and placed them carefully, side by side, like rare specimens, upon the rocks to dry. Then he returned his face to the sun, closed his eyes, and appeared to doze.

Of course, Mr. Wylloe’s information, like the term Indian paintbrush and all other such non-scientific nomenclature, gave me little if anything to go on. A fairy slipper could be anything from a Cypripedium to a Lilium to a Campanula.

I opened my journal and started to write a physical description but then hesitated, removing my colors from my case instead. Perhaps the process of observation and reflection needed to illustrate the specimen would help me come to better know it and, thus, identify it. At least that was my thinking.

Illustrating its precise form was relatively easy. The flower stood atop a small, sheathed stalk which barely held its own in a bed of decaying wood thick with moss. Once I pushed the debris out of the way, I could see that it also had a single basal leaf which was just beginning to emerge.

The flower itself was easy enough to capture on paper, its bilaterally symmetrical petals and prominent lip all easily translated for my visual record. It was not the flower’s form which gave me pause, but rather the color, a shocking pinkish purple with tiger-like stripes tinged along its edges with a golden brown. Sensuous, succulent in the non-botanical sense, if the plant were indeed a slipper, it would be something worn by Titania rather than Puck, if I dare make such a pedestrian literary comparison to you, my dear friend, who is so much better read.

I tried with my colors to capture the plant on paper, but after more than two hours, the day was drawing to a close and my attempts were either too bland, not at all capturing the showiness of the specimen, or too gilded, losing its sense of naturalness in my clumsy translations.

Now it was I who let out a long, exhausted sigh. I returned my glance to Mr. Wylloe, who was watching me closely from his perch on the rock.

“Beautiful, is it not?” he said.

It is showy, I was thinking. A function of survival, I started to note. But for some unknown reason, I said nothing. Jessie, can you believe it? I held my tongue.

But then an even stranger thing occurred. Mr. Wylloe responded to me as if I had spoken. Or as if he had read my mind.

“I meant the setting. You look but you do not see, Miss Bartram. The dappled light, the sound of falling water, the intense green, almost devoid of color in the shadiest corners, your deep concentration. All beautiful.”

It was, indeed, a picturesque setting, but I could not fully appreciate its attractions since I was too frustrated at having failed to capture the true likeness of the plant. I took my hand trowel from my bag and started to remove the specimen, when once again Mr. Wylloe interrupted me.

“Miss Bartram, you surprise me,” he said.

Now I was the impatient one. Again I sighed, but this time I fear it came out sounding more like a snort. Mr. Wylloe had been most generous in his interest in my work, and in his quiet observation, never once interrupting me, focusing his attention instead on the sun, the water, a book of verse he carried in his creel. He appeared to take little interest in what I was doing—or at least he did not interrupt me to learn more about it. In fact, he was such an unobtrusive companion that for that hour or two I thought Mr. Wylloe might prove to be a pleasant addition to my day. Someone I could ignore when it suited me, but still talk to once on the trail headed home. Someone I could write home about, perhaps providing my mother with a reason to be pleased or even proud of my experiences here. In the company of such a man, she would certainly have no reason for concern. But my mother’s concerns aside, I would have to discourage Mr. Wylloe’s interest in my work and decline his offer of companionship if he was going to turn into a bother. From the look on my face he must have understood my concerns.

“Please, I do not mean to intrude, Miss Bartram,” he said, rising from his sunny perch. He moved so slowly that I could almost detect each fragile bone moving inside his skin as he left the creek and walked towards me.

“You are young, and probably unaware of the academic life,” he said, leaning softly against a tree. “I, on the other hand, am experienced when it comes to these sorts of things. You will find that the academic life is a closed world. If you plan to succeed within it, you must play by its rules.”

Now I admit that I knew he was referring to the orchid, Professor Merriam, and the rest, but at the same time I did not have a clue what he really meant. The academic world, even the world of our expedition, is one of science, not sentiment, in spite of the Professor’s foolishness at times. And, yes, science and the academy have their rules, but those are the rules of dispassionate reason. If he meant that I should not remove a specimen because of some Indian’s idea of the sacred—well, you know me, I could not hold my tongue forever.

“Now it is you who must forgive me, Mr. Wylloe, for I wish to acknowledge and respect both your experience and your age. However, like the notion of what is sacred, this is simply outside your ken. There is room for sentiment in things like poetry,” I motioned to the slim volume he carried with him, “but not science. And the academy, with all its acknowledged limitations, does not thrive on sentiment.”

After a pause he spoke. “Perhaps you are right, Miss Bartram. Certainly about the science. However, I hope that even you could admit that the academy does not consist of science, or reason, or even knowledge, but people. It is people, Miss Bartram, with whom you must succeed. With that I will leave you to it.”

And he did. He replaced his hat, slipped his poetry back into his creel, and withdrew, his long white hair and beard reflecting the scattered light as if he were retreating underwater.

Which brings me to why I am boring you with all of this. Jessie, I sat there and sat there like a thwarted child. I revisited the words of Professor Merriam, the way he watched me so intently, his comment that the Indian did not want him to remove the specimen, all of it, but I could no more make sense of the Professor’s wishes than I could of Mr. Wylloe’s. Had the Professor argued that, following scientific protocol, a sole specimen should be left to stand, I would have understood and been forced to comply with his wishes. There would have been no discussion. But this sacred business made no sense to me what so ever.

Given that, I did a very inexplicable thing. I took one last hard look at the orchid, packed my colors and journal and tools, and returned to the trail to await Professor Merriam and the rest of our group. Mr. Wylloe was waiting there as well, although he said nothing when I joined him.

As I write this I am still unsettled with my decision. Even if I did what was right, I am not at all convinced that I did it for the right reason. It pains me to admit it, Jessie, but I left the specimen behind not for science, but for sentiment. Or maybe it was my desire to finally make peace with Professor Merriam, and to be accepted into his company. I am at a loss to otherwise explain it.

That night, when I transferred my specimens to Dr. Rutherford for safekeeping, I could sense Professor Merriam watching me closely. I refused to look back at him, and since he never asked to see the specimen, there is no way he could be certain that I left the orchid behind. But he knew. For something changed between us that night. Time will tell if it is a change for the better.

If I believed in God, I would ask you to pray for me. Something or someone better save me soon, or this whole experience may end up being one in which a promising young woman goes out west in pursuit of science only to return to New York just like any other watcher in the woods, starched and prim, dressed in fairy slippers, with nothing but sentimental love of botany and a mere passion for flowers. Maybe you should pray for me after all.

Your struggling but (still) unsentimental friend,

Alex

Lester King

National Hotel

Mammoth Hot Springs

Yellowstone National Park

June 28, 1898

Dear Mr. and Mrs. Bartram,

I am writing as promised to let you know I have arrived in Yellowstone National Park, although I have yet to rendezvous with Alexandria. I have met with a cavalryman at the Yellowstone headquarters, a Captain Craighead, who will take me to her and her colleagues on Friday. He assures me that the naturalists’ camp, as he refers to it, is an easy ride, and has offered to lend me a horse for the duration of my stay. I prefer, however, to wait for his guidance and expert company since I find it difficult to believe that any destination in this wilderness is an easy ride, the roads in and out of this small valley are so steep and treacherous. To make matters worse, it is now threatening to rain, which could make travel even more dangerous.

That is not to suggest to you that Alex is in any danger. The National Park has a competing wildness and a civility about it which are, in my travelling experience, unique to the human condition. Everyone I have encountered, both on the train ride to the National Park and once here in the hotel, seems to think of themselves as world adventurers, latter day Lewises and Clarks, forging their way through the wilderness and discovering new territories, without fear of the shackles society in its wisdom places upon us elsewhere. These travellers come to the National Park, according to Captain Craighead, to break free of those rules and regulations, and to set their spirits free, to find that even here, at what appears to be the end of the earth, or at least the last stop on the train, the long arm of government regulation has them in their grip.

The National Park requires this government control, according to the captain. Not a day goes by, he informs me, that some fool is discovered carving his initials into a thermal feature or chipping off a piece of a stone formation to take home as a souvenir. With thousands of visitors arriving each year, it would take no time at all before there would be little or no National Park left to visit if it were not for the law and order of Captain Craighead and his men.

Then there are the visitors who throw boulders and large pieces of timber into geyser formations to see if they can block their flow. Of course these idiots are unsuccessful and the debris, I am told, shoots hundreds of feet into the air, often endangering the miscreants themselves and innocent by-standers more than the geysers. Poachers, too, are a problem, having almost wiped out the Park’s big game animals which, thanks to the military’s presence, are just now beginning to recover.

The captain appears to be a young man, wiser than his years, and unsuited for the administrative life he has been assigned to here. He told me he was selected for the post without being consulted and came to the Park against his wishes. However, now that he is here, he is determined to take great interest in his work and do his duty to the best of his ability.

To give you an idea of the kind of degenerate characters he is supposed to control, let me describe a brief encounter I witnessed just yesterday afternoon. As the captain and I were conversing at headquarters, a foreign earl or count of some form of purported European royalty sauntered in under the supervision of two cavalrymen who had apprehended the gentleman and his party on the road into the Mammoth Hot Springs compound. The count in question was fortunate in that he was stopped and questioned as he travelled into the Park, rather than out of it. In his possession was a cache of preserved animals collected throughout the West, including everything from buffalo to elk to prairie dogs to prairie chickens, along with the dogs, ammunition, and alcohol needed to hunt down, kill, and preserve a good deal more.

When questioned by the captain, the count feigned ignorance about Park regulations, he was a scientist and a foreigner after all, but then he took Captain Craighead aside and offered payment for permission to, in his words, collect on the captain’s private reserve. The captain declined, and with his gallant and good nature, explained the National Park’s rules. He suggested, instead, that the count register his specimens with the captain’s office and return for them upon his withdrawal from the National Park.

A simple request to make. Quite another to fulfill. I walked out with them as the count peeled cover after cover from wagons in which his so-called specimens were stored. There were enough preserved animals, and parts of animals including a number of severed heads, to fill a major museum. Or two.

Also in the count’s possession is a full entourage of cooks, butlers, horsemen, musicians, dogs and their handler, the count’s own personal naturalists and taxidermists, who identify and preserve his burgeoning collection of big game animals and birds, and assorted other young men who looked road weary if not out-right debilitated by their employ, the lot of whom sat by waiting for a resolution to be reached between the cavalryman and the count. One young man retreated under his hat and proceeded to snore, an offence for which he was rapped across the knees by the count as he showed the captain around his collection.

“As you can see, my dear sir,” the count explained to Captain Craighead, “I am not a hunter. I have put myself and my men at great risk as we have ventured in the name of science into this western wilderness. You have nothing to fear from me. And the world has much to gain from my studies.”

The captain was resolute. The count was welcome to leave his specimens in the cavalry’s care and enjoy himself while in the National Park, or just as free to leave under escort to the Park’s northern boundary. But the count did not have the option of travelling with his collection unattended within the confines of the National Park, science or no science. As far as Captain Craighead was concerned, there were no other options.

The count walked along the wagons, motioning to the piles of carcasses laid to rest in these large, mobile caskets. As he walked, examining and explaining his collection, pulling up a well-preserved buffalo head for the captain’s closer examination, or unwrapping half a dozen calliope hummingbirds, their diminutive bodies falling into his hand, the count talked of the expenses associated with science, about the costs to all those involved with scientific collections, inferring, in essence, that Captain Craighead, too, must be compensated in some fashion. The captain accompanied the count along the tour of laden wagons, but at the mention again of money the captain lost his composure, and challenged the count to show him just one specimen, in amongst all the slaughter, which would help real scientists, he used those words, better understand the natural world. This was not science, the captain was certain of it, but killing for the simple joy of it.

And with that Captain Craighead raged past me into his office. With resolution reached, the entourage began re-securing the wagons and, after moving them to a shady alleyway next to the headquarters building, proceeded to unhitch and picket the horses for the night. The whole operation could not have taken more than ten or fifteen minutes but during the entire exercise, the count paced and barked orders as if he were being detained for hours.

From there, the remaining entourage, still ten or eleven wagons strong with the count’s bright red buggy in the lead, proceeded down the road to the hotel, where they hitched themselves in a row and began to unload. From the captain’s front porch I watched as four young men wheeled the count’s piano with much effort into the hotel lobby, while another four stumbled along, the count’s large iron bathtub hoisted on their shoulders. Wildness indeed.

As you can see, there are civilizing rules and regulations which, in theory at least, are looking out for the likes of Alexandria. I hope she is looking out for them. All last year, she was forever complaining about the rules and structure of the university and the limits they placed upon her, but what she has yet to understand is that it is through rules and structure and rigid protocols that we gain the freedom for creative work in the sciences. She claims to be enjoying her new-found freedom in the Park. She must be operating under the false assumption that there are no rules or limitations here to protect her from herself.

Captain Craighead has promised to escort me to Alex’s camp on Friday, at which point the captain and I will both take rooms at the Yellowstone Lake Hotel. He plans to be in attendance at a large celebration in honor of Independence Day. I will let you know of my own plans after I have had a chance to speak with your daughter.

In the meantime,

I remain yours,

Lester King

H. G. Merriam

c/o Yellowstone Lake Hotel

Yellowstone National Park

July 3, 1898

Dear Mother,

The U.S. Cavalry has a saying that there are two seasons in Yellowstone, winter and July, but the weather has been at its bleakest in these earliest days of the month. It has been raining steadily for two days, so I find myself trapped inside my tent with Rutherford, his foul-smelling pipe, and his new pet raven, which Rutherford discovered standing by the side of the road, fearlessly gobbling like a turkey for the entertainment of all who passed by.

Rutherford is convinced that if a raven is smart enough to imitate a turkey to beg treats from tourists in the Park, it can just as easily be taught how to imitate a man’s speech. So every time the raven gobbles, it is now rewarded with scraps from Kim Li’s kitchen and is told that it is a “pretty bird.” The strategy, what Rutherford refers to as a scientific experiment, is to see if eventually the bird will not only associate the turkey call with treats, but will also learn to associate the words with the greasy goodies and, thus, learn how to talk.

Is it any wonder that Philip Aber has his doubts about my ability to lead a scientific expedition? Not only does this so-called experiment go on for all hours of the day, but the bird travels everywhere with Rutherford, riding with him in the wagon, sometimes sitting on his shoulder or even on his head.

Journalists are arriving at the hotel to document this weekend’s celebrations and plans for the electric rail line through the Park—plans which are being negotiated as I write. My greatest fear is that one of these journalists will get bored and wander into camp one day, see Rutherford talking to his raven, and the story will be plastered all over the New York and Chicago press. I will be the laughing stock of the scientific community. I can hardly show my face at the hotel as it is, since there is not a person in the Park who has not seen or at least heard about the fat man and his turkey-gobbling bird.