Applications of Humor in Education and in the Workplace

Abstract

This chapter describes the role of humor in the applied areas of educational and industrial-organizational (I/O) psychology. With regard to humor in education, we review relevant research addressing the following questions: (1) How often and in what ways do teachers use humor in the classroom? (2) Does humor affect students’ perceptions of the classroom environment? (3) Does humor improve students' ability to attend, learn, and retain information? (4) Does humor reduce anxiety and improve test performance? (5) Does humor in textbooks help students learn the material? With regard to humor in the workplace, we begin with a discussion of research focusing on humor and organizational culture, exploring ways in which the humor climate of a workplace can be positive or negative. A negative humor climate includes humor-based gender harassment. Finally, we review research on humor and leadership. A theme throughout this chapter is that, both in the classroom and in the workplace, it is important to recognize that humor can be harmful as well as beneficial. Contrary to the claims of some enthusiastic advocates of humor, rather than simply seeking to increase the frequency of humor in these settings, research indicates that it is important to understand the types of humor that are already occurring and the social functions they serve. Thus, while maintaining an open mind about the possible benefits of humor-related applications in these areas, a psychological perspective requires that we carefully sift through the evidence and avoid being carried away by unfounded enthusiasm.

Keywords

Education; educational and industrial-organizational (I/O) psychology; humor; leadership; workplace

Over the past 30 years or so, there has been a growing interest in potential applications of humor in a variety of professional domains. In Chapter 9, The Clinical Psychology of Humor: Humor and Mental Health, and Chapter 10, The Health Psychology of Humor: Humor and Physical Health, we discussed the possible benefits of humor and laughter for mental and physical health, as well as the application of humor in mental and physical health interventions. In this chapter, we explore potential benefits (and possible risks) of humor applied to education and the workplace.

The acceptance and application of humor in educational and workplace settings is a relatively recent phenomenon. Historically, educators and organization leaders have viewed education and work as “serious” activities with no room for play and fun. Educators considered it unscholarly to use humor as a teaching strategy: to entertain was not to educate (Korobkin, 1988; Wandersee, 1982). Similarly, people considered humor, as a form of play, to be the very antithesis of work.

However, pedagogical trends in recent decades have shifted toward the promotion of a more relaxed learning environment and an emphasis on “making learning fun.” The current prevailing philosophy of education argues that students are much more likely to be motivated to learn and to retain information if they are happy and amused than if they are feeling anxious and threatened (Oppliger, 2003). Consistent with this trend, many educators in recent years have recommended that teachers introduce humor into the classroom by sprinkling funny anecdotes, examples, and illustrations throughout their lessons, displaying comical images and sayings on the classroom walls, and encouraging frequent humor production in their students.

Similarly, in recent years, there has been considerable interest in the potential benefits of increasing the amount of humor that occurs in the workplace. People have suggested that a more playful work environment in which humor is encouraged might produce a happier, healthier, less stressed, and more productive workforce, engendering better social interactions among workers and managers, and fostering more creative thinking and problem solving (e.g., Morreall, 1991).

However, many of the early claims that humor advocates made about potential benefits of humor in education and workplace settings were based on anecdotal evidence and personal experience. Therefore, in the following sections, we will explore the relevant empirical findings, weigh the evidence for various claims, and point out questions that still require further study.

The topics of this chapter bring us to the applied areas of educational and industrial-organizational (I/O) psychology. Each of these fields represents a combination of professional practice and science. As practitioners, psychologists working in these fields seek to apply relevant findings and principles derived from the more basic research areas of the discipline to solve real-world problems relating to teaching and education, and the world of business and industry, respectively. As scientists, they conduct empirical research to examine the effectiveness of their interventions and to answer important theoretical and practical questions relating to their fields.

As a consequence of this scientific orientation, applied psychologists tend to be rather skeptical about unsubstantiated claims regarding novel teaching methods or business practices, emphasizing instead the importance of applying empirical methods to investigate the validity of these sorts of practices. Thus, while maintaining an open mind about possible benefits of humor-related applications in these areas, a psychological perspective requires that we carefully sift through the evidence and avoid being carried away by unfounded enthusiasm.

Humor in Education

Many educators have written popular books and scholarly articles promoting humor as an effective teaching tool with far-reaching benefits, claiming that it: reduces anxiety associated with the classroom setting creating a more positive attitude toward learning; reduces boredom and makes learning more fun; enhances student–teacher relationships; stimulates interest in and attention to educational messages; increases comprehension, retention, and performance; promotes creativity and divergent thinking (Berk & Nanda, 1998; Davies & Apter, 1980; Ziegler, Boardman, & Thomas, 1985). Accordingly, Cornett (1986) described humor as one of the teacher’s “most powerful instructional resources” (p. 8). Given that humor seems to make students more comfortable in the educational settings, some have suggested that the use of humor is especially beneficial in teaching students about sensitive, anxiety-arousing topics such as death and suicide (Johnson, 1990), and in teaching courses that are typically associated with negative attitudes and anxiety, such as undergraduate statistics (Berk & Nanda, 1998).

Many enthusiastic endorsements of humor are based on anecdotal evidence and teachers’ reports of their own experiences in the classroom, and empirical research on the effects of humor in educational settings is unfortunately quite limited (Teslow, 1995). Nonetheless, there is some research on humor in education addressing the following questions:

- 1. How often and in what ways do teachers use humor in the classroom?

- 2. Does humor affect students’ perceptions of the classroom environment?

- 3. Does humor improve students’ ability to learn and retain information?

- 4. Does humor reduce anxiety and improve test performance?

- 5. Does humor in textbooks help students learn the material?

In the following sections, we review research findings addressing each of these questions, followed by some general caveats concerning the use of humor in education (for more detailed reviews of research in this area, see Banas, Dunbar, Rodriguez, & Lui, 2011; Bryant & Zillmann, 1989; Oppliger, 2003; Teslow, 1995).

How Often and in What Ways Do Teachers Use Humor in the Classroom?

A number of observational studies have shown that college instructors use humor quite frequently in the classroom (e.g., Bryant, Comisky, Crane, & Zillmann, 1980; Downs, Javidi, & Nussbaum, 1988; Javidi & Long, 1989). Bryant et al. (1980) analyzed tape recordings of lectures by university professors and found that professors exhibited an average of 3.34 instances of humor per 50-minute class period. Downs et al. (1988) found that a sample of award-winning professors used humor an average of 7.44 times per class. Interestingly, Javidi and Long (1989) reported that more experienced professors used humor in class more often (an average of 6.50 times per 50-minute class period) than inexperienced professors (an average of 1.60 times per 50-minute class period).

It appears that high school and middle school teachers use humor in their classrooms less than do college professors (Bryant & Zillmann, 1989; Gorham & Christophel, 1990; Neuliep, 1991). In one comparative study, for instance, Javidi, Downs, and Nussbaum (1988) found that college professors made just over seven attempts at humor per class; high school teachers made just 2.80 and middle school teachers made only 2.33. Similarly, James Neuliep (1991) conducted a large-scale survey of high school teachers and found that teachers reported attempting to use humor only 2.08 times per class.

In addition, there has been some evidence that male college professors and school teachers use humor in their classrooms more frequently than females do (Bryant et al., 1980). Bryant et al. (1980) further reported that male and female college professors used different types of humor. Men tended to tell more jokes and funny stories; women used more spontaneous humor that was relevant to the course material. Although men and women might use humor in educational settings differently, it is important to note that differences between them in the amount and type of humor are either small or inconsistent (Canary & Hause, 1993; Gorham & Christophel, 1990; Van Giffen, 1990).

What kinds of humor do teachers actually use and for what purposes? To address these questions, researchers have conducted surveys and observational studies to document the types or forms of humor that instructors use in the classroom (e.g., Bryant et al., 1979; Frymier, Wanzer, & Wojtaszczyk, 2008; Gorham & Christophel, 1990; Neuliep, 1991; Torok, McMorris, & Lin, 2004; Wanzer, Frymier, Wojtaszczyk, & Smith, 2006), as well as the functions for which instructors use humor (e.g., White, 2001).

Joan Gorham and Diane Christophel (1990) asked college students to keep diary recordings of all their instructors’ humorous comments and activities over the course of five class periods. Overall, they collected 1396 instances of humorous comments, anecdotes, jokes, or physical forms of comedy. Content analyses of student responses revealed 13 categories of humor based largely on whether the humor contained tendentious (sexual or aggressive) content or not, and the referent of the humor. Perhaps their most notable finding was that instructors often engaged in humor that students perceived as inappropriate (inducing negative student affect and serving negative educational functions; Frymier et al., 2008). Indeed, Gorham and Christophel coded over 50% of all the instructors’ instances of humor as tendentious or aggressive, in that they involved some form of disparagement or ridicule. A full 20% of their humor included ridicule or teasing directed at an individual student (e.g., “She made a comment about the guy that always comes in late.”) or the entire class (e.g., “Said he’d cancel class before break because he doubted any of us would show up anyway.”). Other tendentious humor targeted the topic or subject of the course, the instructor’s academic department, the university, the state, or famous people at the national or international level. About 12% of the humor was targeted at the instructors themselves, in what might be described as self-deprecating or perhaps self-defeating humor. Less than half of the college instructors’ humor did not have an obvious target. These nontendentious forms of humor included either personal or general anecdotes and stories that were either related or unrelated to the subject of the lecture, “canned” jokes, and physical or vocal comedy (“schtick”). In all, only about 30% of the humor was related to the lecture topic.

In another study, James Neuliep (1991) conducted a large-scale survey of high school teachers asking them to describe the most recent situation in which they had used humor in the classroom. Neuliep coded responses to develop a taxonomy of teachers’ humor based on the following categories:

- 1. Teacher-directed humor: self-deprecation, describing an embarrassing experience.

- 2. Student-targeted humor: joking insult, teasing a student about a mistake.

- 3. Untargeted humor: pointing out incongruities, joke-telling, punning, tongue-in-cheek or facetious interactions, humorous exaggeration.

- 4. External source humor: relating a humorous historical incident, showing a cartoon that is related or unrelated to the subject, humorous demonstrations of natural phenomena.

- 5. Nonverbal humor: making a funny face, humorous vocal style, physical bodily humor.

Although teachers seemed to be generally aware of the potential risks of using aggressive forms of humor directed at students, humor involving teasing, insults, and joking about students’ mistakes still accounted for more than 10% of their overall humor.

More recently, Melissa Wanzer and colleagues (Wanzer et al., 2006) asked 284 undergraduate college students to describe examples of appropriate humor—humor that was not offensive and/or was fitting for the class—that they had observed their teachers use in the classroom, as well as examples of inappropriate humor—humor that was offensive and/or was not fitting for the class. Students generated a total of 1315 distinct instances of humor (774 instances of appropriate humor; 541 instances of inappropriate humor). Wanzer et al. then placed the instances of appropriate and inappropriate humor into conceptually distinct categories depicted in Table 11.1.

Table 11.1

| Category label | Percentage of instances of inappropriate humor |

|---|---|

| Inappropriate instances of humor | |

| 1. Disparaging humor-targeting students: remarks that clearly disparaged students as a group or as individuals based on qualities such as appearance, intelligence, or gender | 42 |

| 2. Disparaging humor-targeting others: responses that criticized nonstudent groups of people based on sex, race, religion, or sexual orientation | 27 |

| 3. Offensive humor: remarks students viewed as distasteful including humor that was sexual, morbid, vulgar, or inappropriate | 30 |

| 4. Self-disparaging: jokes, stories, or comments in which an instructor criticizes or belittles him/herself | 1 |

It is noteworthy that students sometimes perceived self-disparaging humor as an appropriate form of humor in the classroom and other times perceived it as inappropriate. Thus, self-disparaging humor can function as a double-edged sword to be used with caution. Wanzer et al. suggested that it has the potential to grab students’ attention, as students perceive it as more unexpected than other forms of humor. They also recognized, however, that it also has the potential to create anxiety among students.

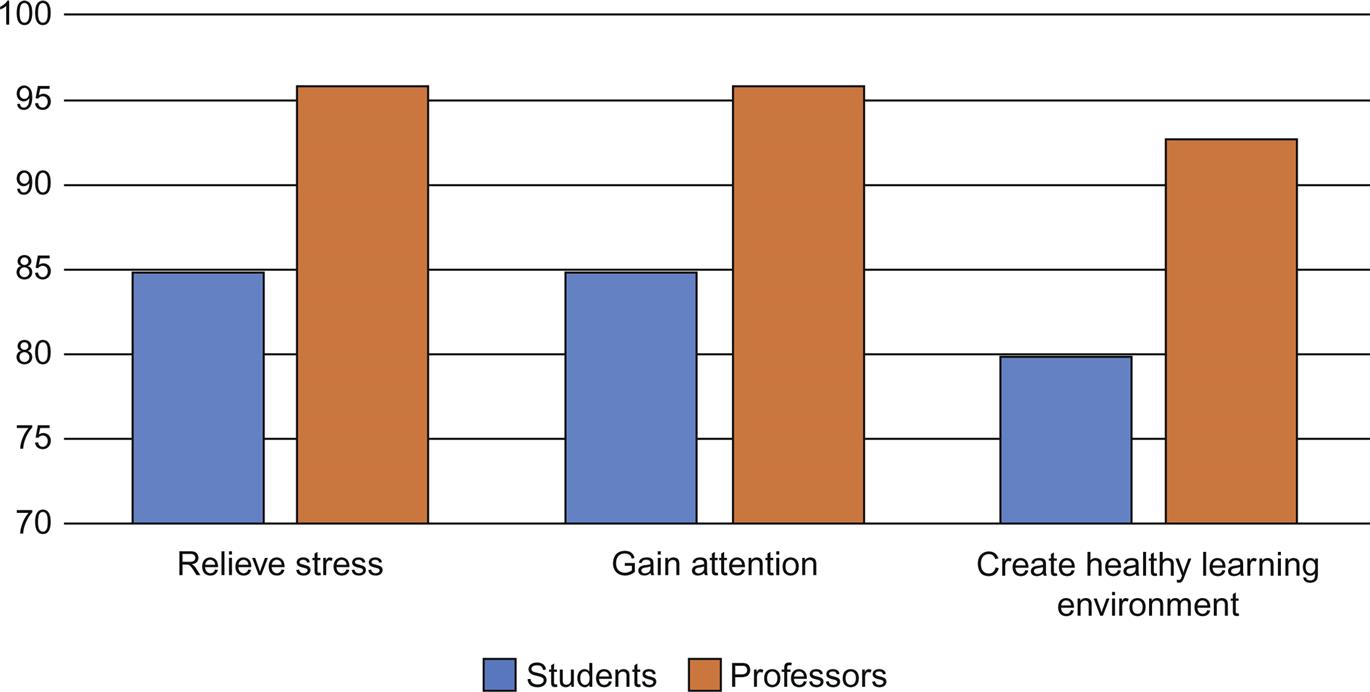

Gayle Webb White (2001) developed a survey to determine how, or for what function, college instructors use humor in the classroom. She collected responses on the survey from 128 faculty members in education, business, science, and math from 12 public and private universities in Arkansas. Then, she collected responses from 206 students attending 65 different colleges or universities. White found that professors and students generally agreed on how professors used humor in the classroom, although professors thought they used humor more for positive purposes and less for aggressive purposes compared to students. Consistent with Korobkin (1989) the highest percentage of professors and students reported that professors used humor to relieve stress, gain attention, and create a healthy learning environment (see Fig. 11.1).

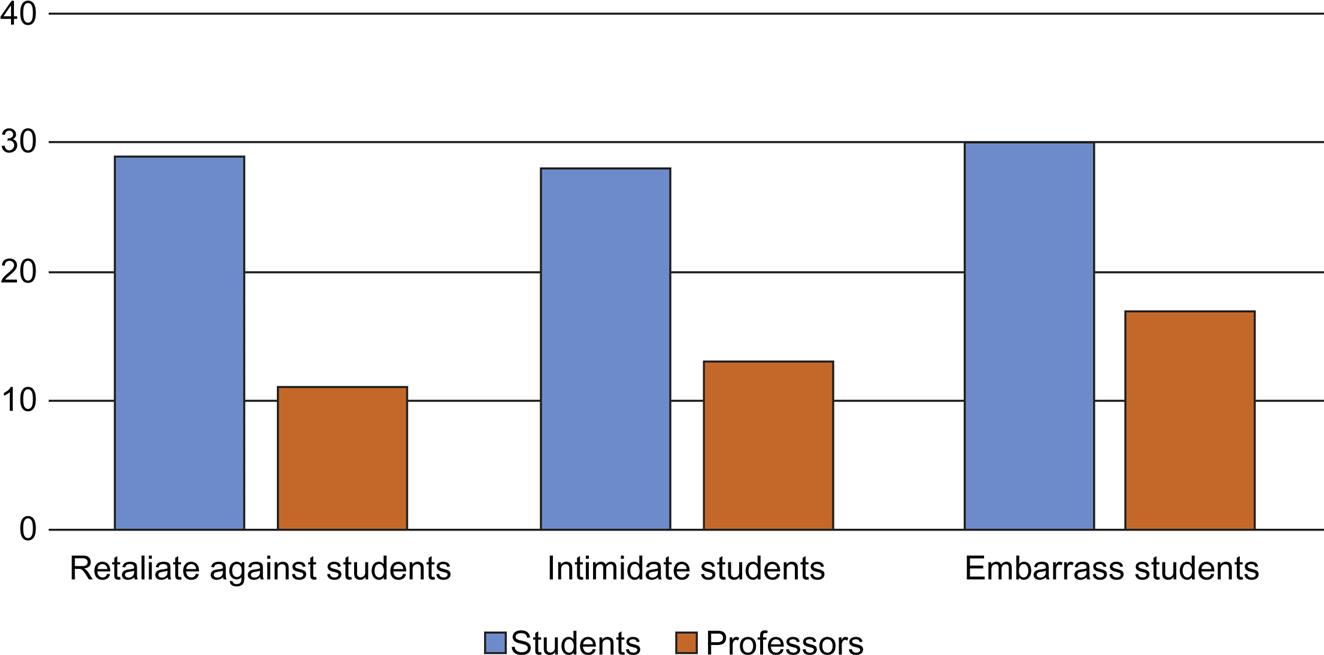

Students and professors also reported that professors sparingly use aggressive, disparaging forms of humor to retaliate against students, to intimidate students, or to embarrass students (see Fig. 11.2).

As can be seen in Fig. 11.2, professors particularly reported rarely using aggressive forms of humor. Perhaps with the emergence of political correctness norms in the 1990s and, along with them, the controversy over the use of disparagement humor (e.g., Barker, 1994), college professors have become more sensitive to the potentially harmful effects of teasing and ridiculing students and have intentionally tried to refrain from such humor. However, consistent with findings by Gorham and Christophel (1990) and Wanzer et al. (2006), professors’ attempts at humor appear to come off as more aggressive to the students: nearly 30% of the students reported that professors use humor for each of the three aggressive functions.

Students and professors showed more disagreement in their perceptions about the degree to which professors use humor to motivate students, provoke thinking, and reinforce knowledge. On average, 80% of professors reported that they use humor to accomplish these goals. However, only 55% of the students perceived professors as actually accomplishing these goals through humor. It appears that professors intend to use humor to motivate, stimulate thinking, and reinforce knowledge, but that students perceive they are not particularly good at it. Finally, contrary to Mallard’s (1999) recommendations, only 15% of professors reported attempting to use humor to handle unpleasant or tense situations.

In summary, college professors and school teachers appear to use humor in a wide variety of ways for many purposes. Researchers’ taxonomies of the types and functions of instructional humor vary. However, the most important distinction appears to be whether the humor is appropriate (inducing positive student affect and serving positive educational functions) or inappropriate (inducing negative student affect and serving negative educational functions). Both instructors and students see appropriate instructional humor as particularly effective in relieving stress, gaining students’ attention and creating a healthy learning environment. Also, teachers have become increasingly aware of the potential risks of engaging in potentially inappropriate aggressive forms of humor directed at students.

Does Humor Affect Students’ Perceptions of the Classroom Environment?

Does instructional humor improve the classroom environment and make learning more enjoyable? Research on this question has provided evidence that instructional humor positively affects students’ perceptions of their instructors and the quality of the classroom environment.

Students evaluate instructors that use appropriate forms of humor more positively (e.g., Gorham & Christophel, 1990; Tamborini & Zillmann, 1981; Wanzer & Frymier, 1999). Indeed, surveys have shown that students rate sense of humor as one of the most important attributes of an effective teacher (Check, 1986; Fortson & Brown, 1998; Powell & Andresen, 1985). Observational studies corroborate these findings. Bryant et al. (1980), for instance, tape-recorded college lectures. They found a positive relationship between student evaluations and the extent to which instructors told funny stories and jokes. Students evaluated instructors who told more funny stories and jokes as more effective, more appealing, better at delivering course material and better overall. They did not, however, perceive them as more competent or intelligent (Bryant et al., 1980). Importantly, students give negative evaluations of instructors that use aggressive forms of humor. For instance, Gorham and Christophel (1990) found that students evaluated college instructors more negatively to the extent they engaged in ridicule or teasing. Similarly, Torok et al. (2004) found that students negatively evaluated instructors they felt overused offensive humor and sarcasm.

Looking beyond the effect of humor on student perceptions of instructors, research suggests that the use of appropriate instructional humor positively relates to students’ perceptions of the quality of the classroom environment. The more instructors use humor in class, the more students perceive they learn, and the more they like the course content (e.g., Garner, 2006; Gorham, 1988; Strean, 2011). Garner (2006), for instance, conducted an experiment in which college students reviewed three hour-long lectures on research methods and statistics that either did or did not include several funny stories. Garner found that students in the humorous condition reported more positive overall opinions of the lectures, reported that the lectures were communicated more effectively, and rated the instructor more positively, compared to those in the nonhumorous condition. Finally, other research has shown that instructional humor reduces the level of stress students perceive in the classroom (Berk, 2000; Berk & Nanda, 2006; Chiarello, 2010).

The positive relationship between the use of instructional humor in the classroom and students’ perceptions of instructors and the quality of the classroom environment might be explained by different underlying mechanisms. First, it might be due to the role of humor in promoting a sense of immediacy. In educational settings, immediacy refers to the degree to which an instructor makes a close personal connection with students, as opposed to remaining distant and aloof (Andersen, 1979). Instructors create immediacy by telling personal stories, encouraging students to participate in class discussions, addressing students by name, praising students’ work, and looking and smiling at the class while speaking. Humor might be another strategy by which instructors can foster immediacy in their relationship with their students. Past research has shown that greater levels of immediacy are associated with more positive student attitudes toward the class and instructor, greater enjoyment and motivation, and greater perceived learning (Andersen, 1979; Gorham, 1988; D. H. Kelley & Gorham, 1988). Thus, immediacy might be the critical mechanism that mediates the relationship between instructional humor and student perceptions.

In Gorham and Christophel’s (1990) study mentioned earlier, college students observed and recorded their professors’ humor attempts, and they rated the degree to which their professors engaged in a variety of verbal and nonverbal immediacy behaviors. Gorham and Christophel found a positive correlation between the number of the professors’ humor attempts and students’ ratings of their overall immediacy. Professors with higher overall immediacy scores also engaged more in instructional humor and they used less tendentious and self-disparaging humor. Furthermore, Wanzer and Frymier (1999) found that college students’ ratings of the degree to which professors engaged in humor were positively associated with measures of the instructors’ immediacy and responsiveness to students. In addition, analyses revealed that the significant associations found between instructors’ humor and students’ course evaluations and perceptions of learning were largely (but not entirely) accounted for by immediacy. Thus, humor might be one component of a broader set of teacher behaviors that contribute to a sense of immediacy in the classroom, which in turn results in more positive teacher and course evaluations and greater perceived learning in the students.

Second, the relationship between the use of instructional humor and students’ perceptions might be due to the positive affect that humor creates. Students do not typically expect instructors to use humor in the classroom (Frymier & Weser, 2001). Thus, students might be pleasantly surprised when instructors do use humor, leading them to perceive their instructor and classroom environment more positively. In addition, the positive affect that humor generates might help relieve tension and anxiety (Teslow, 1995), thereby promoting more positive perceptions of the learning environment.

Does Humor Improve Students’ Ability to Attend to, Learn, and Retain Information?

As discussed above, instructors can use appropriate forms of humor in the classroom to foster a positive classroom environment for their students. Perhaps the more important question for educators, however, relates to more academic or instructional outcomes: does instructional humor improve students’ ability to attend to, learn, and retain information?

Regarding the relationship between instructional humor and attention, empirical research has produced consistent findings that instructional humor draws and holds students’ attention, at least in young children. Wakshlag, Day, and Zillmann (1981), for instance, found that when given a choice of educational television programs to watch, first- and second-grade children preferred those containing humor, especially if the humor was fast-paced. Zillmann, Williams, Bryant, Boynton, and Wolf (1980) found similar effects of instructional humor and concluded, “the educator who deals with an audience whose attentiveness is below the level necessary for effective communication should indeed benefit from employing humor early on and in frequent short bursts” (p. 178).

However, although instructional humor appears to grab students’ attention, it does not necessarily facilitate learning and retention of information. Indeed, empirical research on learning and retention has turned up mixed findings over the years. Several studies have found no relationship between instructional humor and student learning outcomes (e.g., Bryant, Brown, Silberberg, & Elliott, 1981; Gruner, 1967; 1976; Houser, Cowan, & West, 2007; Kennedy, 1972; Markiewicz, 1972). Bryant et al. (1981), for example, used cartoon illustrations to vary the degree of humor associated with educational material presented to college students. They found that the humorous illustrations had no effect on students’ ability to learn new information. Charles Gruner (1976) reviewed nine studies and concluded that all except one failed to show any influence of humor on learning. Outside of the educational context, early research on the effects of humor on memory for speeches also generally found no differences in learning between humorous and serious speeches (Gruner, 1967).

More recently, Houser et al. (2007) presented college students with a DVD recording of a lecture on interpersonal attraction. In the “high humor” condition, the instructor included comical stories, examples, and jokes that were written into the script along with pauses to create good comedic timing and the perception that the instructor was funny. In the “low humor” condition, the instructor did not include jokes, and provided bland rather than funny examples and stories. After hearing the lecture, students completed a five-question recall test. Houser et al. found no effect of instructor humor on students’ performance on the recall test, suggesting that instructional humor made no difference in student learning of new information.

Other studies, however, have demonstrated that instructional humor facilitates learning and retention (e.g., Davies & Apter, 1980; Kaplan & Pascoe, 1977; Kelley & Gorham, 1988; Wanzer & Frymier, 1999; Ziv, 1988). Ann Davies and Michael Apter (1980) randomly assigned children between the ages of 8 and 11 to view either humorous or nonhumorous versions of several 20-minute audio-visual educational programs on topics such as language, science, history, and geography. The humorous versions of the programs were identical to the nonhumorous versions except for a number of funny cartoons. In support of the hypothesis that humor enhances learning, testing revealed that the children in the humorous condition recalled a significantly greater amount of information than did those in the nonhumorous condition, both immediately after the presentations and at 1-month follow-up.

Avner Ziv (1988b) provided further evidence that instructional humor can facilitate learning. Criticizing earlier studies for their methodological flaws, artificiality, lack of ecological validity, and short duration, Ziv examined the effects of humorous lectures on student performance in an actual statistics course over a whole semester. In his first experiment, he randomly assigned students in the course to either the “humor” condition or the “no-humor” condition. The same instructor taught the course in both the humor and no-humor conditions. Ziv trained the instructor to use humor relevant to the course material in the humor condition according to a strict protocol. In the humor condition, the instructor introjected three or four funny jokes, anecdotes, or cartoons into each lecture to illustrate certain key concepts. First, the instructor presented a given concept, then used humor to illustrate the concept, and finally paraphrased the concept. The instructor presented the same concepts with an equal amount of repetition in the no-humor condition. Ziv found that students in the humor condition attained significantly higher course grades and performed approximately 10 percentage points better on the final exam than did those in the no-humor condition.

Ziv replicated these findings in a second experiment using two classes of female students taking an introductory psychology course at a teachers’ college. Once again, students in the humor condition achieved an average grade that was about 10 percentage points higher than those in the no-humor condition. In his discussion of these results, Ziv argued that the stronger findings of these two experiments, compared with the generally disappointing earlier educational research on this topic, may have been due to the fact that the humor was directly relevant to the course material, it was limited to only a few instances per lecture hour, and the instructors were trained to use it effectively.

Although Ziv’s and other more recent studies suggest that instructional humor can indeed facilitate student learning, the conflicting findings over the years raise questions about how and under what conditions it affects student learning. Accordingly, Wanzer, Frymier, and Irwin (2010) developed their Instructional Humor Processing Theory (IHPT) to explain the processes by which instructional humor facilitates learning, and thus delineate when it does and when it does not facilitate learning.

IHPT proposes that students must recognize and resolve an incongruity in the instructor’s message to perceive humor. The relevance of the humor to course material and how students interpret the humor (i.e., as appropriate or inappropriate) jointly determine whether it should facilitate learning. Specifically, when students interpret the humor as appropriate for the context, it will elicit a positive affective reaction; if they interpret it as inappropriate, it will elicit a negative affective reaction. Based on Petty and Cacioppo’s (1981) Elaboration Likelihood Model of persuasion, Wanzer et al. proposed that the positive affect elicited by appropriate humor motivates students to engage in greater cognitive elaboration of the humorous message. If appropriate humor is also related to course material or makes the material more relevant to the students, the humor would also make it easier for students to process the material. Thus, by increasing both motivation and ability to engage in cognitive processing, appropriate humor related to course material should facilitate learning. In contrast, appropriate humor that is not related to course material might be expected to increase motivation to engage in cognitive processing because of the positive affect it elicits, but it should not affect the ability to process information because it is not strategically connected to the course material. Finally, IHPT predicts that humor that students view as inappropriate for a classroom (e.g., ridicule, teasing, offensive humor, etc.) should interfere with learning because it elicits negative affective reactions, and thus reduces motivation to process information.

The positive relationship between humor and learning generally has been corroborated by research in cognitive psychology regarding the effects of humor on memory (Derks et al., 1998; Schmidt, 1994, 2002; Schmidt & Williams, 2001). As we saw in the review of this research in Chapter 5, The Cognitive Psychology of Humor, these experiments provide quite consistent evidence that humorous information is recalled better than nonhumorous information when both are presented in the same context. If only humorous material is presented, however, there is no apparent benefit for memory. Moreover, it is important to note that the enhanced recall of humorous material occurs at the expense of memory for any nonhumorous material that is presented at the same time. In other words, the inclusion of humorous illustrations in a lecture may enhance students’ memory for the humorous material, but it might also diminish their memory for other information in the same lecture that is not accompanied by humor. These findings suggest that, if instructors wish to use humor to facilitate students’ learning of course material, they should ensure that the humor is closely tied to the course content. In addition, the constant use of humor throughout a lesson will have little effect on retention. Instead, humor should be used somewhat sparingly to illustrate important concepts and not peripheral material.

Does Humor Reduce Anxiety and Improve Test Performance?

Psychological and educational research has consistently shown that anxiety hurts performance on examinations in classroom settings (e.g., Carrier & Jewell, 1966; Daniels & Hewitt, 1978; Marso, 1970; Mazzone et al., 2007). Daniels and Hewitt (1978), for instance, found that college students who scored high on Sarason and Gordon's (1953) Test Anxiety Questionnaire performed worse on four regular course exams than did students who were categorized as having moderate or low test anxiety. Anxiety affects performance by interfering with the cognitive processes in working memory that are required to complete cognitive-intellectual tasks (e.g., Arkin et al., 1982; Ashcraft, 2002; Ashcraft & Kirk, 2001; Eysenck & Calvo, 1992).

As we saw in Chapter 9, The Clinical Psychology of Humor: Humor and Mental Health, exposure to humorous material facilitates coping with stressful events by reducing state anxiety and negative affect (e.g., Berk, 2000; Berk & Nanda, 1998, 2006; Cann et al., 2000; Isen et al., 1987; Newman & Stone, 1996; Yovetich et al., 1990). Moreover, since exposure to humorous material reduces state anxiety, and lower levels of state anxiety are associated with better performance on tests of cognitive-intellectual skills, it follows that exposure to humorous stimuli could enhance performance on course examinations.

Researchers historically have investigated this possibility by testing whether students perform better on multiple-choice examinations that contain some humorous questions or a humorous response option compared to exams containing no humor. In one early study, Smith, Ascough, Ettinger, and Nelson (1971) gave students with varying degrees of test anxiety either a humorous multiple-choice midterm exam (one third of the questions were designed to be humorous) or a nonhumorous exam (none of the questions were designed to be humorous). Smith et al. found that highly anxious students performed better on the humorous exam than on the nonhumorous exam, and they performed equally as well on the humorous exam as students who had either moderate or low levels of anxiety. Furthermore, highly anxious students performed worse on the nonhumorous exam than did those who had moderate or low levels of anxiety. Smith et al.'s findings suggest that humorous exams can benefit students that have high test anxiety.

However, subsequent studies have failed to show that humorous exams alleviate test anxiety or improve performance (e.g., McMorris, Urbach, & Connor, 1985; Perlini, Nenonen, & Lind, 1999). McMorris, Boothroyd, and Pietrangelo (1997) reviewed 11 studies that examined the effect of humorous versus nonhumorous test questions on performance. They concluded that there is no convincing evidence that humorous tests lead to better overall performance compared to nonhumorous tests. In fact, the only clearly significant main effect indicated poorer performance among students receiving the humorous version of a test. Based on failures to replicate Smith et al.'s findings, Perlini et al. (1999) concluded that, “…efforts to introduce humor to examinations to alleviate test anxiety may be misdirected…” (p. 12).

Overall, then, there is little evidence that humorous test items improve students’ performance. However, when asked about their reactions to the humorous versions of the tests, the vast majority of students perceived them to be enjoyable and helpful rather than detrimental to their performance. In their review of this literature, McMorris and colleagues (1997) concluded that, although there is no evidence that humor in tests either helps or hinders students’ performance, the judicious use of humor may be beneficial in making exams more enjoyable to the students. They noted, though, that it is important to ensure that the humor is positive, constructive, and appropriate for the students.

Although embedding humor into the content of an examination probably will not improve performance, exposure to humorous material prior to the exam might. Cann et al. (2000) found that exposure to a humorous videotape reduced the amount of anxiety experienced in response to a stressful event only when it was presented prior to the stressful event. Humor served a preventive function, inhibiting anxiety evoked by the anticipated stressful event. Perhaps, then, exposure to humor prior to taking a difficult test can enhance performance by inhibiting anxiety. Berk and Nanda (2006) addressed this possibility. They gave graduate students in a biostatistics course tests on course material that contained either (1) humorous instructions presented before the test, (2) content-relevant humor in test questions, or (3) humorous test instructions and humorous questions. Consistent with Cann et al. (2000), Berk and Nanda found that only humorous instructions presented before the test positively affected performance. However, none of the humor manipulations affected test anxiety, thus the study failed to support the hypothesis that anxiety reduction mediates the effect of humor on test performance.

However, Berk and Nanda (2006) may not have provided a fair test of the mediating role of anxiety. The graduate student participants showed very low levels of test anxiety before taking the exams and before the induction of the humor manipulation. They knew about the exams well in advance and had the opportunity to prepare for them. In addition, the course instructor employed several strategies, unrelated to humor, that were designed to minimize test anxiety. As Berk and Nanda suggested, the premanipulation levels of test anxiety were so low that there was little room for humor interventions to reduce anxiety further. Thus, it remains possible that exposure to humor prior to taking a test can enhance performance, in part, by inhibiting anxiety associated with the test.

Ford et al. (2012) tested this possibility. These researchers hypothesized that exposure to humorous material prior to taking a difficult and stressful math test could (1) inhibit the amount of state anxiety associated with the anticipated test, and thus (2) enhance performance. Accordingly, they told participants that they would take a difficult math test. Before giving the test, however, they asked participants to read either 10 funny cartoons, 10 nonhumorous short poems, or nothing at all. Participants then completed the math test that consisted of questions taken from the quantitative section of practice SAT tests. Then participants completed Spielberger, Gorsuch, and Lushene’s (1970) state anxiety scale. Participants rated the extent to which they felt: anxious, comfortable, jittery, worried, at ease, nervous, and calm while taking the test.

The results supported their hypotheses. Participants performed better on the math test and experienced less anxiety associated with the test in the cartoon condition than in the poem condition or the control condition. Further analyses revealed that exposure to the humorous cartoons prior to taking a difficult math test enhanced performance on the test because they alleviated the amount of state anxiety that participants felt while taking the math test. Ford et al. argued that the humorous cartoons created a positive affective state that is incompatible with anxiety, and thus inhibited anxiety enough to prevent it from interfering with task-relevant processing (e.g., developing problem-solving strategies). This interpretation is consistent with research showing that exposure to humorous stimuli serves as a protective function against the negative effects of anxiety associated with a stressful event (Cann et al., 2000). However, further research is necessary to delineate other psychological mechanisms besides anxiety that might mediate the effect of exposure to humor on test performance.

Does Humor in Textbooks Help Students Learn the Material?

Many high school and college textbooks contain funny cartoons and other humorous materials to illustrate the information in the text. Does the inclusion of such humor actually help students to learn the material better? In one study designed to investigate this question, Bryant et al. (1981) randomly assigned college students to read different versions of a chapter of a college textbook containing either no humor, moderate amounts of humor, or extensive humor in the form of cartoons illustrating points in the text. Next, they administered a recall test to all the students. They found no differences in recall performance among students in the three humor conditions and concluded that humorous cartoons did not affect student learning of textbook material. However, students enjoyed reading the humorous versions of the chapter more than the nonhumorous version. Interestingly, though, they rated the humorous versions as less persuasive and revealing lower author credibility. Finally, the humor manipulation did not affect students’ ratings of interest, likelihood of reading more of the book, or likelihood of taking a course with this book as the text.

In another study, Klein, Bryant, and Zillmann (1982) asked college students to rate a randomly assigned chapter from an introductory psychology textbook on a number of dimensions such as level of interest, enjoyableness, and persuasiveness. They then recorded the amount of humor contained in each chapter. They found a positive correlation between students’ enjoyableness ratings and the amount of humor chapters contained: students reported greater enjoyment of more humorous chapters. However, Klein et al. found no relationship between the amount of humor in the chapters and students’ ratings of interest, persuasiveness, capacity for learning, or desire to read more on the topic. Overall, then, the current findings suggest that humor in textbooks may be useful for boosting student appeal (and perhaps increasing the likelihood of adoption by course instructors), but it does not seem to improve students’ ability to learn the information or their perceptions of the credibility of the book.

Caveats in the Use of Humor in Education

Most educators who advocate the use of humor in teaching are careful to note that aggressive forms of humor such as sarcasm, ridicule, or put-down humor have no place in the classroom. Nonetheless, as Jennings Bryant and Dolf Zillmann (1989) pointed out, research indicates that many teachers do actually use hostile forms of humor with their students, including ridicule, sarcasm, and teasing. These types of humor may be perceived by some teachers as a potent method of correcting undesirable behavior in their students such as tardiness, inattention, failure to complete assignments, disruptive behavior, and so on. By teasing or ridiculing a student, teachers may feel that they can correct individual students as well as setting an example for the rest of the class. Indeed, research evidence suggests that these techniques may be quite effective as behavioral deterrents, since observing another person being ridiculed can have a powerful inhibiting effect on children’s behavior by the time they reach 6 years of age (Bryant et al., 1983).

However, there is also abundant evidence that ridicule and other forms of aggressive humor can have a detrimental effect on the overall emotional climate of a classroom. For example, in a study discussed in Chapter 8, The Social Psychology of Humor, college students who observed another person being ridiculed became more inhibited, more conforming, and fearful of failure, and less willing to take risks (Janes & Olson, 2000). The research by Gorham and Christophel (1990) discussed earlier also indicates that teachers who use more aggressive forms of humor in the classroom are evaluated more negatively by their students. Clearly, the use of humor to poke fun at students for their ineptness, slowness to learn, ignorance, or inappropriate behavior can be damaging, creating an atmosphere of tension and anxiety, stifling creativity.

Another potential risk of humor in education, particularly with younger children, is that it might be misunderstood and lead to confusion (Bryant & Zillmann, 1989). Humor often involves exaggeration, understatement, distortion, and even contradiction (e.g., in irony). These types of humor might inadvertently cause students to fail to understand the intended meaning and to learn inaccurate information. Because of the novelty of the images that such distorting humor can convey, such inaccuracies may also be particularly easy to remember and especially resistant to memory decay.

These potential risks of humor with primary school children are supported by two studies finding that educational television programs containing humorous exaggeration or irony led to distortions in children’s memory for the information being taught (Weaver, Zillmann, & Bryant, 1988; Zillmann et al., 1984). These memory-distorting effects of humor were found in children from kindergarten to grade four. Interestingly, even when the researchers added statements that identified and corrected the factual distortions introduced by the humor, this was not enough to overcome the distorting effects of humor on children’s recall. The authors of these studies concluded that the vividness of the humorous images was recalled and not the verbal corrections. Thus, teachers of young children who use humor need to be careful to ensure that their humorous statements are not misunderstood.

Summary

As with humor in all types of social interactions, the role of humor in education turns out to be more complex than it might first appear. Consistent with our conclusions about humor in psychotherapy in Chapter 9, humor seems to be best viewed as a form of interpersonal communication that can be used for a variety of purposes in teaching. Instructors can use humor in beneficial ways to illustrate pedagogical points, to make lessons more vivid and memorable, and to make the learning environment more enjoyable and interesting for students. On the other hand, they can use humor in inappropriate or negative ways that demean students, which can distract students’ attention away from more important points or distort their understanding of course material. As Bryant and Zillmann (1989) observed, success in teaching with humor “depends on employing the right type of humor, under the proper conditions, at the right time, and with properly motivated and receptive students” (p. 74).

Existing empirical research suggests that when instructors use appropriate forms of humor in the classroom, students rate the instructors more positively, express greater enjoyment of the course, and report learning more. The judicious use of humor seems to be particularly beneficial in increasing the level of immediacy in the classroom, reducing the psychological distance between teachers and students.

In addition, there is evidence from naturalistic classroom studies, as well as some recent well-controlled laboratory experiments on humor and memory, indicating that information that is presented in a humorous manner is remembered better than information presented in a serious way when both occur in the same context. However, the enhanced learning of humorous material occurs at the expense of poorer learning for nonhumorous information. Instructors who wish to use humor in their lessons to help students remember the material should therefore be careful to use humor sparingly and to associate it with key concepts rather than irrelevant information.

Finally, there is little evidence that the inclusion of humorous questions on tests reduces test anxiety and improves test performance, although it does make tests more enjoyable. There is evidence, however, that exposure to humorous material prior to taking a difficult, stressful test can alleviate anxiety associated with the test, and thus improve performance. Also, including funny cartoons and illustrations in textbooks does not appear to facilitate students’ ability to learn material in the text, but it does make textbooks more enjoyable to the students.

Humor in the Workplace

Just as educators have historically viewed education as serious business with no room for play and fun, organizational scholars have also viewed work, organizations, and business as the antithesis of humor and frivolity. Over the past few decades, however, managers have shown an interest in understanding the potential ways that humor can benefit their organizations (Westwood & Johnston, 2013). Indeed, business magazines and trade journals have published many articles extolling the benefits of humor in the workplace (e.g., Duncan & Feisal, 1989), and authors have written popular books designed to instruct organizations on how they can use humor to benefit their business (e.g., Gostick, 2008; Kerr, 2015; Kushner, 1990; Tarvin, 2012). Although research evidence for a link between worker happiness and productivity is controversial (Iaffaldano & Muchinsky, 1985; Judge, Thoresen, Bono, & Patton, 2001), the assumption seems to be that the improved rapport, teamwork, and creativity resulting from humorous interactions will not only make for a more enjoyable work environment, but will also translate into greater productivity and a better bottom line for the company.

These ideas have also given rise to a new type of business consultant that specializes in the promotion of humor at work (Gibson, 1994). Organizations frequently hire “humor consultants” to conduct workshops and seminars in which they teach employees how to become more playful and humorous at work. These professionals also produce newsletters, websites, books, and audiotapes proclaiming the benefits of workplace humor. While cautioning against the use of inappropriate and offensive types of humor, they advocate that workers engage in playful activities such as telling funny stories during breaks, making a collection of jokes and cartoons to look at during times of stress, and posting amusing baby pictures of fellow employees on workplace instant messaging forums.

Humor consultants range in qualification and experience, from seasoned psychological researchers who hold advanced degrees, to motivated business professionals (Robert, 2017). As Gibson (1994) pointed out, they typically view humor from a functionalist or utilitarian perspective. That is, they see humor as a planned activity that one can exploit for the benefit of an organization. Accordingly, their workshops and seminars tend to contain common themes. For instance, humor consultants typically advocate humor use that does not question or challenge the corporate status quo. Second, they promote the use of humor at work that appeals to both management and employees by giving both a greater sense of control. Employees use humor as a tool for gaining control over stress levels and relationships with fellow workers, while managers often gain a sense of control over their employees by using humor to increase employee motivation, productivity, and efficiency. Although there does not appear to be empirical research testing the effectiveness of these sorts of humor interventions in business, their continued popularity suggests that they meet with a receptive audience among both workers and management.

Unfortunately, the increasingly popular utilitarian treatment of humor in the workplace has to some extent “delegitimized” the study of humor among many organizational scholars (Westwood & Rhodes, 2007), resulting in the conduct of relatively little research on humor compared to other organizational topics (Westwood & Johnston, 2013). Despite these sorts of concerns, organizational scholars have begun to conduct an increasing amount of research on humor in organizations over the past decade, focusing particularly on the links between humor and organizational culture and between humor and leadership.

Humor and Organizational Culture

As Holmes and Marra (2002) pointed out, organizational scholars have not reached consensus on a single definition of organizational culture (Frost, Moore, Reis Louis, Lundberg, & Martin, 1991). However, they generally agree that organizational culture is comprised of shared values, norms or rules of behavior, traditions, and stories that bind members of an organization together and give it a distinctive identity (e.g., Deal & Kennedy, 1982; Ostroff, Kinicki, & Muhammad, 2013; Smircich, 1983). Organizational culture essentially emerges out of the interactions of people who work together, and humor appears to be a pervasive feature of workplace interactions (Holmes & Marra, 2002). Westwood and Johnston (2013), for instance, stated, “[e]ntering almost any organization or workplace almost inevitably entails an encounter with humor, and with some frequency in most cases” (pp. 220–221). Thus, an organization’s “humor climate” plays an important and fundamental role in shaping organizational culture (e.g., Blanchard, Stewart, Cann, & Follman, 2014; Holmes, 2000; Holmes & Marra, 2002; Holmes & Stubbe, 2003; Rogerson-Revell, 2007; Westwood & Johnston, 2013). Blanchard et al. (2014) defined humor climate as the shared perception of how employees in a work group use and express humor. An organization’s humor climate can be either positive or negative, having beneficial or detrimental effects on organizational culture by affecting the psychological wellbeing and performance of individual employees and by affecting the quality of interactions among workers.

Positive Humor Climate and Organizational Culture

In a positive humor climate employees and managers share humor without excluding or negatively targeting anyone. They engage in affiliative and self-enhancing humor in the form of amusing anecdotes and joking comments that serve to reinforce friendly and collegial relationships (Holmes & Marra, 2002) (see Fig. 11.3).

In her classic study, Karen Vinton (1989) conducted a participant observation of humor use in a small family-owned business. Vinton observed that positive (affiliative) humor in the form of anecdotes, friendly teasing, and witty banter served several positive functions for individual employees such as relieving stress and enhancing job satisfaction. It also served broader social functions relating to the social interactions and coworker relationships: it provided a means of socializing new employees into the organization, reduced status differentials between people, facilitating cooperation, and provided a way of diffusing conflict.

More recently, Romero and Arendt (2011) examined the relationship between Martin et al.’s (2003) humor styles and (1) stress, (2) satisfaction with coworkers, (3) team cooperation, and (4) organizational commitment among employees in organizations of different sizes in a variety of different industries. They found that positive humor styles predicted positive outcomes, whereas negative humor styles related to negative outcomes. First, Romero and Arendt found that affiliative and aggressive humor styles predicted both stress and satisfaction with coworkers. Employees who have an affiliative humor style might experience less job stress and greater satisfaction with coworkers because they use humor as a way to reduce stress-inducing interpersonal tensions and maintain positive relationships with others (Martin et al., 2003; Hampes, 2005). In contrast, those who use humor in an interpersonally aggressive manner experience more stress-inducing interpersonal tensions and have poorer interpersonal connections with their coworkers.

Interestingly, Romero and Arendt did not find the self-enhancing or self-defeating humor styles to be related to job stress. This is surprising given Cann and Etzel’s (2008) findings that these two self-directed humor styles related more strongly to psychological wellbeing than the two other-directed humor styles. Perhaps job-related stress is particularly dependent on the quality of interpersonal relationships one has with others in their immediate environment.

Finally, Romero and Arendt found that both affiliative and self-enhancing humor styles related positively to team cooperation and organizational commitment (degree of identification with the organization; Meyer, Allen, & Smith, 1993) and that an aggressive humor style negatively related to team cooperation and organizational commitment. They suggested that because employees with an affiliative humor style tend to be “other focused” and concerned with maintaining positive interpersonal connections, they are likely to be more cooperative with coworkers and committed to their organization. Similarly, those with a self-enhancing humor style tend to be more extraverted and agreeable (Martin et al., 2003; see Chapter 4: The Personality Psychology of Humor), and thus more cooperative and committed to the organization. In contrast, an aggressive humor style negatively relates to agreeableness and conscientiousness, and positively relates to hostility. This general interpersonal negativity is reflected in less team cooperation and organizational commitment.

Other research has also shown beneficial effects of positive humor. Positive, friendly teasing and banter between colleagues reduces boredom (Plester & Sayers, 2007), facilitates coping with stress (Plester, 2009), and increases cohesion or solidarity among coworkers (Janes & Olson, 2015; Romero & Pescosolido, 2008). Further, it induces positive emotions, which in turn contribute to desirable outcomes such as increased productivity and creativity (Van den Broeck, Else, Dikkers, de Lange, & Witte, 2012). Positive humor also helps employees make sense of ambiguous events (Blanchard et al., 2014). Mesmer-Magnus, Glew, and Viswesvaran (2012) conducted a meta-analysis of positive humor in the workplace, analyzing data from 49 different studies. They found that employees’ use of positive humor resulted in a number of positive outcomes. Positive humor enhanced job performance and satisfaction, team cohesion, physical health, psychological wellbeing, and coping skills. It also decreased employee burnout, stress, and withdrawal. In general, it appears that a positive humor climate can facilitate positive psychological and physical wellbeing and act as a protection against workplace stress.

A positive humor climate also plays an important role in smoothing social interactions, particularly during times of conflict or tension (Plester, 2009). Some scholars, for instance, have suggested that humor facilitates negotiations and mediation. Forester (2004) suggested that the use of humor in mediation is more than simply telling jokes. Rather, it alters perspectives, changes expectations, reframes relationships, and provides alternative views on a topic.

Mulkay, Clark, and Pinch’s (1993) observational study of humor use in sales negotiations between a parts supply salesman and a potential buyer from a photographic equipment shop illustrate these positive functions of humor. The salesman and the potential buyer used humor to deal with difficulties and to avoid confrontation, allowing each to better achieve their goals. For example, the prospective buyer used a great deal of humor as a way of refusing to buy the salesman’s products, requesting concessions, halting a persistent sales pitch, suggesting that the prices were too high, and hinting that the goods were of inferior quality. For his part, the salesman used humor to overcome the buyer’s resistance, to make fun of his various excuses for not buying the products, and to forestall further criticism. Each person used humor to express his views without appearing overly confrontational. In general, it appears that humor can provide a nonthreatening, socially acceptable way to voice conflict or criticism (Holmes & Marra, 2002).

Viveka Adelsward and Britt-Marie Oberg (1998) also conducted qualitative research on the role of humor in business negotiations and meetings between potential buyers and sellers. They found that both parties used humor to signal a desire to move on to a different topic without appearing too abrupt or controlling, and to smooth tensions and find common ground. Similarly, Carmine Consalvo (1989) observed that humor and laughter occurred most frequently during transition points in managerial meetings, such as when group members moved from a problem-identification phase to a problem-solving phase in their discussions. She concluded that humor at these times signaled a willingness to work together to solve the problem and conveyed an open, accepting, and mutually supportive attitude among group members.

Negative Humor Climate and Organizational Culture

In a negative humor climate employees and managers use humor aggressively, to disparage, tease or ridicule others, to enforce social norms, or to undermine existing power relationships (Blanchard et al., 2014). People can direct negative humor toward others who are outside the immediate work group, or toward those who are part of the work group. Blanchard et al. suggested that negative humor directed outside the immediate work group typically addresses working conditions and organizational policies or the ideals of the larger organizational community (Dwyer, 1991; Holmes & Marra, 2002; Taylor & Bain, 2003). In a review of sociological studies of humor in the workplace, Tom Dwyer (1991) noted that workers often use humor to joke about the inadequacies of managers, to complain about poor working conditions, and to protest seemingly arbitrary rules. Likewise, managers use negative humor to mask the authoritarian nature of a message or to create divisions among subordinates, so as to weaken their collective power.

In an observational study, David Collinson (1988) described the use of negative humor directed outside the immediate work group and within the work group. He observed shop-floor workers in the parts division of a truck factory in England. He noted that the workers engaged in nearly constant joking, humorous banter, witty repartee, and horseplay in their interactions with one another. They engaged in positive humor that functioned as a way of finding fun and releasing tension in the monotony of tightly controlled, repetitious work tasks, and negative humor that served the subversive function of expressing resistance to the social organization of the company. For example, they often derogated and made fun of managers and white-collar staff, emphasizing the workers’ self-differentiation from, and antagonism toward, these “out-groups.” In addition to expressing antagonism and resistance toward management, workers directed negative humor toward one another as a way to enforce conformity to social norms. They engaged in a good deal of highly aggressive teasing, sarcastic put-downs, and practical jokes, which seemed to be a way of communicating and enforcing group norms and expectations, particularly concerning behaviors associated with working-class masculinity. Anyone who deviated from these social norms would be subjected to constant teasing and practical jokes, providing a powerful incentive to conform. Furthermore, Dwyer observed that higher-status team members initiated such negative forms of humor more often than lower-status members.

As illustrated in Collinson’s (1988) study, Blanchard et al. (2014) suggested that negative humor directed toward members of one’s own work group tends to involve denigrating, disparaging teasing or ridicule. One form of such humor that has received considerable research attention is sexist humor, humor that denigrates, demeans, stereotypes, or oppresses a person on the basis of his or her gender (LaFrance & Woodzicka, 1998; Sev’er & Ungar, 1997). Research has shown that gender harassment in the form of sexist jokes and teasing is the most commonly experienced type of sexual harassment by women in the workplace (e.g., Duncan, Smeltzer, & Leap, 1990; Fitzgerald et al., 1988; Gruber & Bjorn, 1982; Pryor, 1995a, 1995b). For example, Fitzgerald et al. (1988) surveyed 2599 undergraduate and graduate students, as well as faculty and staff at two universities. Among all participants, they found that humor-based gender harassment (e.g., suggestive stories or offensive jokes) was the most frequently reported experience of sexual harassment among five dimensions of sexual harassment assessed by their Sexual Experiences Questionnaire. Over 31% of the female student respondents and 34% of the working women respondents reported experiencing some form of humor-based gender harassment, whereas only 15% of the students and 17% of the working women reported experiencing more serious forms of sexual harassment. Similarly, Pryor (1995a) used data from a survey of over 2600 employees from a government agency and found that gender harassment in the form of sexual teasing and jokes was the most frequently experienced form of sexual harassment among women. Pryor also (1995b) found that gender harassment (i.e., sexual teasing, sexist jokes) was the most common form of harassment reported among female military personnel. In fact, 82% of harassed military women experienced sexist joking in one form or another.

The interpretation of sexist humor in the workplace depends on the status of the humorist relative to the disparaged target. What is seen as innocent horseplay coming from a coworker may be viewed as inappropriate sexual harassment coming from a supervisor. Hemmasi, Graf, and Russ (1994) found that the same sex-related jokes—either sexual or sexist—were more likely to be viewed as sexual harassment when a male supervisor initiated them than when a male coworker initiated them. Similarly, Giuffre and Williams (1994) interviewed wait staff who worked with members of the same and opposite sex at a restaurant. Almost all of the respondents described their work environment as “highly sexualized” (p. 381). Sexist jokes, sexual innuendo, and teasing were commonplace. Three women and one man reported being sexually harassed by their manager. Interestingly, though, all four reported similar behaviors from their coworkers, but did not label the behaviors as sexual harassment. Rather, they dismissed them as “only joking” (p. 384). They interpreted sexist joking and teasing from coworkers as positive humor, as innocuous or benign expressions of camaraderie. However, they interpreted the same behaviors performed by a supervisor negatively, and labeled them as sexual harassment.

The different reactions to sexist joking by coworkers and superiors may be due to different role expectations ascribed to them. People have conceptions of the prototypical instances of discrimination—behaviors that represent the “best” or “classic” examples of discrimination. Furthermore, instances that match these prototypes are more readily viewed as discrimination than those that do not (Baron, Burgess, & Kao, 1991; Inman & Baron, 1996; Inman, Huerta, & Oh, 1998). Relevant to perceptions of potential sexual harassment, men have traditionally occupied positions of power and authority, and sexual harassment often is viewed as an attempt to assert or maintain power and authority over women (Montemurro, 2003; Thacker & Ferris, 1991). Thus, a male superior denigrating a female subordinate likely conforms to common conceptions of the prototypical or classic case of sexual harassment. As a result, women are more likely to perceive sexual harassment in sexist jokes told by a superior than by a coworker. Ironically, Pryor (1995b) reports, in a survey of military women, that sexual harassment was perpetrated most often by coworkers (45% of all cases).

Collectively, these findings highlight the need for managers—especially men—to be sensitive to the ways in which their joking may be interpreted. In fact, it would be prudent to advise managers to avoid sexually oriented comments altogether (Hemmasi et al., 1994).

In summary, an organization’s humor climate can be either positive or negative, and thus have beneficial or detrimental effects on organizational culture. In a positive humor climate, employees and managers share humor without excluding or negatively targeting anyone. A positive humor climate can benefit the psychological wellbeing and performance of individual employees, as well as the quality of relationships among employees in work groups. In contrast, a negative humor climate involves the use of aggressive humor in the form of disparagement or ridicule in order to enforce social norms, exclude individuals, emphasize divisions between groups, or to undermine existing power relationships. Unlike positive humor, negative humor can have a detrimental impact on organizational culture.

In view of the complexity and paradoxical qualities of humor, it seems rather simplistic and naïve to suggest, as some humor consultants do, that simply increasing the level of humor and fun in an organization will necessarily result in many desirable changes and improved productivity. Since humor is already ubiquitous in the workplace, serving many different functions and reflecting the social structures and power dynamics of the organization, the task for managers seems to be not so much to increase the level of fun and laughter, but to understand the meaning of the humor that already exists and to attempt to channel it in productive directions (Box 11.1).

Humor in Leadership

A good sense of humor is often considered to be an important characteristic for a leader, along with other attributes such as intelligence, creativity, persuasiveness, and general communication skills. Research on leadership behavior indicates that effective leadership requires skills in the general areas of (1) giving and seeking information, (2) making decisions, (3) influencing people, and (4) building relationships (Yukl & LepSinger, 1990). These broad skill areas have been further divided into a variety of component behaviors, many of which are related to interpersonal relations and communication, such as the ability to communicate and get along well with subordinates, peers, and superiors, to manage conflict, motivate others, and enhance group cohesion and cooperation. Humor can be viewed as an important communication skill that is potentially useful to leaders and managers in many of these areas. For example, the use of humor could be beneficial for teaching and clarifying work tasks, helping to motivate and change behavior, promoting creativity, coping with stress, and generally making the interactions between the manager and subordinates more positive and less tense (Decker & Rotondo, 2001).

The psychology of leadership and ways in which leaders can be most effective has historically been a topic of considerable interest, but has attracted even greater attention over the past few decades. The manner in which leaders incorporate humor into their organizations is an important area of this research because it often plays a key role in how leaders communicate with their employees. Leader–member exchange (LMX) theory suggests that leaders and followers develop unique relationships based on their social exchanges, and the quality of these exchanges within an organization can influence employee outcomes (Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995; Liden et al., 1997). Humor can be a contributing factor during such exchanges, and the frequency (Hughes & Avey, 2009) and type of humor (Wisse & Rietzschel, 2014) that leaders exhibit can shape followers’ perceptions of their leader.

Survey studies have examined the correlation between sense of humor and perceived leadership qualities by asking workers to rate their supervisors on various dimensions. In a survey of 290 workers, Wayne Decker (1987) found that those who rated their supervisors as being high in sense of humor also reported greater job satisfaction and rated these supervisors as having generally more positive leadership characteristics as compared to participants who rated their supervisors as low in sense of humor (see Fig. 11.4).

Similarly, Robert Priest and Jordan Swain (2002) found that military cadets perceived leaders they felt were good or effective as having a warmer, more competent, and benign humor style; they perceived leaders they felt were bad or ineffective as having a colder, ineffective, and mean-spirited humor style.

In his 2009 paper, Larry Hughes proposed that a leader’s style of humor delivery has an impact on workers’ positive emotions (e.g., joy, contentment, interest) and creative performance. He identified three main styles of humor delivery: self-deprecating (leaders make fun of themselves), other-deprecating (leaders make fun of the focal person in the social situation), and nonsense style (the target of the humor is not the leader nor another person in the situation, but a neutral target). Hughes further suggested that followers’ positive emotions mediate the relationship between leader humor and followers’ creative performance.

In a later study, Deog-Ro Lee (2015) examined how leaders’ humor styles influence employee creativity, as well as the moderating effects of employees’ trust in their leader. Using 316 leader–follower pairs from five telecommunication organizations in South Korea, Lee showed that leaders’ use of self-enhancing humor correlated positively with employees’ creativity, while leaders’ use of aggressive humor was negatively associated with employees’ individual creativity. Importantly, employees’ level of trust in their leader moderated the relationship between a leader’s use of self-enhancing humor and employee creativity; when employees trusted their leader, the leader’s use of self-enhancing humor was associated with greater employee creativity. In contrast, insofar as employees did not trust their leader, the leader’s use of self-enhancing humor was associated with less employee creativity.

Researchers have also shown interest in whether humor uses and their outcomes may differ for leaders based on gender or race. Wayne Decker and Denise Rotondo (2001), for instance, conducted a study to determine whether a leader’s use of positive and negative humor has different outcomes depending on the leader’s gender. Decker and Rotondo asked employees in a variety of organizations to indicate the extent to which their manager used positive humor (e.g., enjoyment of jokes, use of humor in daily conversation) and negative humor (e.g., sexual humor, ridicule). They also rated their manager’s overall leadership effectiveness. They found that employees rated their managers as more effective insofar as they used positive humor, and less effective insofar as they used negative humor. Furthermore, this pattern of results was stronger for female than male managers. That is, the use of positive humor by female versus male managers was more strongly associated with workers’ positive perceptions of their leadership skills. By the same token the use of sexual and other negative forms of humor was more strongly associated with workers’ negative perceptions of their leadership skills in female compared to male managers.

Overall, these studies provide evidence that employees perceive supervisors who use positive humor as more effective leaders; leaders who use humor inappropriately tend to receive more negative evaluations of their leadership skills. These findings could suggest that greater sense of humor might cause a leader to be more effective, but perhaps not. The findings could just reflect a “halo effect,” whereby greater overall liking of a supervisor may cause employees to perceive him or her as having a better sense of humor as well as better leadership skills. Further research is necessary to more fully delineate the direction of causality in the relationship between leaders’ use of humor and employee outcomes.

Summary and Conclusion

Organizational scholars have begun to conduct more research on humor in organizations over the past decade, recognizing the link between humor and organizational culture and between humor and leadership. An organization’s humor climate—its shared perceptions of how employees in a particular work group use and express humor—can either have beneficial or detrimental effects on individual employees and on the quality of interactions among employees.

In a positive humor climate employees and managers engage in affiliative and self-enhancing humor in the form of amusing anecdotes and joking comments that serve to reinforce friendly and collegial relationships. Such positive uses of humor appear to have beneficial outcomes such as lowered job-related stress, less boredom, greater satisfaction with coworkers, greater team cooperation, and greater cohesion among employees and organizational commitment. In a negative humor climate employees and managers use humor aggressively, to disparage, tease, or ridicule others, to enforce social norms, or to undermine existing power relationships. Negative uses of humor seem to have a detrimental impact on employees and their relationships with one another. One particularly negative type of humor is the use of derogatory humor as a form of (gender) harassment. In view of the complexity of humor, it seems rather simplistic and naïve to suggest, as do some humor consultants, that simply increasing the level of humor and fun in an organization will necessarily result in many desirable changes and improved productivity.