LOS ALAMOS, NEW MEXICO

APRIL 22, 1945

5:00 P.M.

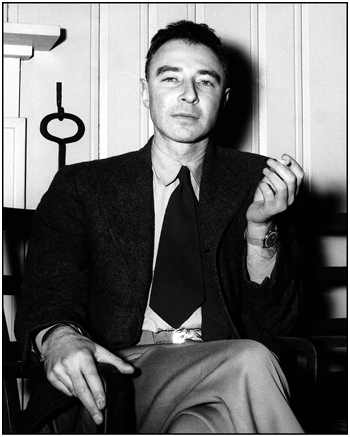

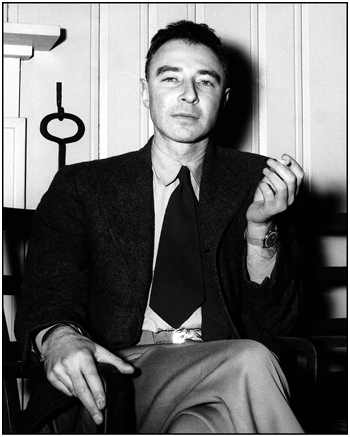

The most dangerous man in the world is celebrating his forty-first birthday. Sipping on a dry gin martini, the eccentric and brilliant physicist, J. Robert Oppenheimer, moves from conversation to conversation in the living room of his 1,200-square-foot stone-and-wood cottage. The air smells like pipe tobacco. His guests are physicists, chemists, and Nobel Prize winners, their accents British, American, and Eastern European.1

Everyone in the room has a top secret security clearance, allowing them to speak freely about a topic few in the world are aware of. With Germany all but defeated, these brilliant minds are divided between those who want to see the atomic bomb dropped on Japan and those who believe it is morally wrong to destroy a country so near to surrender. Some believe that dropping the A-bomb will lead to a worldwide arms race. Indeed, the Hungarian physicist Leo Szilard is making secret plans to meet with President Truman to discuss this troubling matter in person.2

The altitude in Los Alamos is 7,300 feet atop a desert mesa. Newcomers often find themselves unable to handle their liquor because the thin air brings dizziness. But Oppenheimer’s drinking stamina is legendary among his staff, surpassed only by his obsessive drive to create the world’s first atomic weapon. Even after this Sunday night of celebration, Oppenheimer will rise well before the 7:30 a.m. factory whistle blows.

* * *

“My two great loves,” Robert Oppenheimer wrote to a friend long before the war, “are physics and desert country. It’s a pity they can’t be combined.”

Now, thanks to Brigadier General Leslie Groves and the top secret Manhattan Project, they have been. It has been six years since Franklin Roosevelt’s Oval Office meeting with Alexander Sachs and its resulting call to action for America to pursue nuclear weapons. But it has been less than three years since Oppenheimer was tasked by the overweight army bureaucrat with not only building a state-of-the-art laboratory in the middle of nowhere but also convincing some of the world’s sharpest minds to put their lives on hold to spend the rest of the war here.

Oppenheimer was not the obvious choice to be in charge of the lab. His past indicated some trouble: the young professor from the University of California at Berkeley had a history of depression and eccentric behavior. In the late 1930s, Oppenheimer dated a woman known to be a member of the Communist Party, which concerned army counterintelligence and the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Also, Oppenheimer had no experience managing a large group of people, nor had he won a Nobel Prize. Many doubted that he had the experience required to build the world’s first weapon of mass destruction.

Yet the outspoken Groves was determined to hire him. “Oppenheimer can talk to you about anything. He can talk to you about anything you bring up. Well, not exactly.… He doesn’t know anything about sports,” Groves would later tell an interviewer, referring to Oppenheimer as “a genius.”

Word of a new laboratory devoted to splitting atoms eventually filtered into the scientific community. At the time of Oppenheimer’s hiring, in October 1942, some were shocked at the “most improbable appointment.” As one physicist noted: “I was astonished.”

A twenty-five-year-old boys’ school thirty-five miles northwest of Santa Fe with log dormitories and a stunning view of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains was soon purchased to build Oppenheimer’s new lab. Included in the $440,000 price were 8,900 acres of land, sixty horses, fifty saddles, and one phone line. The school, named Los Alamos, was soon ringed with security fences topped with coils of razor wire and guarded by military personnel and attack dogs. Oppenheimer’s scientists begin to feel so secure that many stop locking their front doors when they leave for work in the morning. That safety, however, comes at a cost: each employee at the Los Alamos National Laboratory is subject to constant monitoring of his or her personal life by security personnel. News of the atomic bomb research must be kept from reaching Germany and the Soviet Union.3

What began as a theoretical laboratory soon became a small town. A theater group was formed, with Oppenheimer himself making a cameo appearance as a corpse in Arsenic and Old Lace. A town council was elected. Parties were common and lasted late into the night, sometimes featuring the world’s most learned minds playing piano or violin to entertain their friends. Some found the remote location to be claustrophobic, while others thought it romantic, leading to an extraordinarily high birth rate.

As 1944 becomes 1945, and the testing of an actual A-bomb begins, the physical and emotional toll of transforming a weapon that once existed only in theory into a violent force that could end the largest war in history has been debilitating. Oppenheimer stands almost six feet tall but has wasted away to just 115 pounds. His teeth are rotting. He smokes five packs of Chesterfield cigarettes a day and is prone to long fits of smoker’s cough that turn his face purple. He rarely eats, having abandoned his passion for spicy food in favor of a diet of gin, cigarettes, and coffee.

Worse, Oppenheimer’s wife of five years, Kitty, a genius in her own right in the field of botany, has broken under the strain. She has gone home to live with her parents in Pittsburgh, taking their four-year-old son, Peter, with her. Strangely, Kitty leaves their four-month-old daughter, Toni, behind. Knowing that Oppenheimer will not be able to care for the baby, she has entrusted the child to Pat Sherr, a good friend who has just suffered a miscarriage. The truth is that Kitty has never been a good mother to Toni, whom she sees as an unwanted burden, frequently abandoning her to the company of friends for days at a time.

J. Robert Oppenheimer

Robert Oppenheimer visits his daughter twice a week, though his own love for his daughter is just as precarious as that of his wife. Juggling parenting and the upcoming testing of the atomic bomb is too much for him. On one occasion he asks Sherr if she would like to adopt Toni, explaining that he “just can’t love her.” An appalled Sherr declines.

Robert Oppenheimer longs for Kitty’s return. She is his sole confidante and one of the few people he can trust.4

Yet in Kitty’s absence, there are rumors. Despite his cadaverous look and the smell of stale tobacco that clings to him like a shroud, some women are drawn to Oppenheimer. He is not oblivious to their charms; talk of affairs follows him throughout his time at Los Alamos. Among the rumors (although it appears to have been nothing more than that) is one of a liaison with a pretty blond twenty-year-old secretary, Anne T. Wilson, whom Oppenheimer handpicked for the job upon meeting her in Washington.

Oppenheimer’s relations with other women, however, go far beyond rumor. In June 1943, he rekindled an old romance with pediatric psychologist Jean Tatlock while on a business trip to Berkeley. Army intelligence agents, who were spying on Oppenheimer’s every move due to the high security surrounding the Manhattan Project, reported that he had dinner and drinks with Tatlock before spending the night in her apartment. Years before, in the midst of a torrid relationship, Tatlock had turned down Oppenheimer on three separate occasions when he asked her to marry him. It was a decision she would come to regret by 1943. Six months after Oppenheimer spent the night, Jean Tatlock drew a bath, swallowed a bottle of sleeping pills, and died.

* * *

Another of Oppenheimer’s affairs is with Ruth Tolman, a psychologist for the Office of Strategic Services who is ten years older than Oppenheimer. This affair will continue long after the war’s end. Tolman’s husband is also employed at Los Alamos and soon learns of his wife’s infidelity. When Ruth’s husband, Richard, dies of a heart attack in 1948, some will claim that despondence over his wife’s love of Oppenheimer was a primary cause.

Right now, however, Robert Oppenheimer has little energy to stray. His “gadget,” as he calls the A-bomb, is almost ready for testing. The detonation, when it occurs, will take place in the nearby desert, the Jornada del Muerto—or “Journey of the Dead Man,” as this barren, windswept landscape is appropriately known. The site has been chosen because it is remote, unpopulated, and flat.

Robert Oppenheimer graduated from Harvard with honors in just three years and has a PhD in physics from Germany’s University of Göttingen. He is a natural leader who enjoys the spotlight but rarely shows his true emotions.

Among his varied interests, Oppenheimer is a believer in Eastern philosophy. His code name for the upcoming A-bomb test is “Trinity,” after the three Hindu gods Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva.5 Oppenheimer can quote the Hindu scripture, the Bhagavad Gita, at will: “If the radiance of a thousand suns were to burst into the sky, that would be like the splendor of the mighty one.… Now I am become death, the shatterer of worlds.”6

As his birthday party progresses, Oppenheimer shakes another martini with great flair. The cocktail is one of his personal trademarks. Although he drinks constantly, the scientist prefers to sip his libation slowly and rarely becomes inebriated.

Robert Oppenheimer’s life is full of contradiction. But as his favorite selection from the Bhagavad Gita suggests, this man who chose to play a corpse onstage, and whose body now wastes away as he deprives it of simple nourishment, is a real-life Grim Reaper.

And he knows it.