FOOD DOES NOT HAVE TO BE ELABORATE. IN FACT SIMPLE preparations can be genuinely delicious. However, preparing things simply is deceptively difficult, since there is no way to hide any oversights. Care and attention are crucial.

When food is always fancy or elaborate, then fanciness becomes quite ordinary, and we forget the plain, full-natured, actual taste of things. Living in a world of created taste, we think that we can make everything suit our fancy. We reject foods that do not suit our cultivated taste, which gets increasingly particular the more we cater to it. Soon enough we have quite a low level of tolerance, of willingness to experience the unfamiliar. When we are open to ordinary goodness, not always comparing a particular taste with what we are used to, then we can experience and appreciate the actual taste of things. Though the taste is not like we thought it would be, the flavor comes home to our hearts.

When I was young, I couldn’t stand eating vegetables. The very sound of the word evoked something frightfully distasteful. “At least try it” was always the command, on occasion reluctantly obeyed. I mainly ate frozen peas and frozen green beans. Then in eighth grade a girl made a show-and-tell salad with sour cream and basil dressing, and I started eating lettuce. When I was in high school, my mother cooked cabbage with wine, and I started eating cabbage. Since then my vocabulary of edible vegetables has increased enormously. Only brussels sprouts give me pause, but I cook and eat them anyway—occasionally.

The recipes in this chapter have very few measurements. Essentially I am crediting everyone with an ability to sense things for themselves. The size of vegetables varies, appetites vary, tastes vary. Numbers can be fairly arbitrary. If you like onions, put more in; if you don’t like carrots, use less. “Spinach with Onion and Carrot” could be “Onion with Carrot and Spinach” or “Carrot with Spinach and Onion.”

Vegetables can be cooked much more precisely by taste and experience than they can by numbers. You know how full the salad bowl needs to be to serve everyone, which bowl (or combination of bowls) needs filling in order to make a vegetable dish. Cook more when it’s a dish you and your family just love and can’t get enough of. Cook less when it’s a dish that people aren’t so fond of, or perhaps one that you’re trying out for the first time.

You’re the cook. What I call cooked may be someone’s half raw. It’s a tentative designation. What I call overcooked may be someone’s favorite way of preparation. Don’t cook for me, cook for yourself, and for those who will be eating.

VEGETABLES

Whatever is done will not make a cucumber more of a cucumber or a radish more of a radish. What is done may make a vegetable more suitable to some particular taste—that’s the ordinary way, to see what taste we want. But why not “ask” the cucumber, why not “ask” the radish? What is the taste it would like to express? Welcome it into your mouth, into your experience: ask and listen.

Practicing Zen with Vegetables

Nowadays we are often advised to eat the best, to enjoy the freshest. And we shop for only the finest. I guess I’m in another school. My Zen teacher, Suzuki Roshi, would buy the worst-looking vegetables. “Who will use them if I don’t?” he would ask. The grocery clerk would try to dissuade him, “Wouldn’t you like something fresher?” When his wife joined him here in America from Japan, she wouldn’t let him go shopping anymore.

It’s an ancient Zen tradition, not wasting anything, including leftovers: we understand that the way you treat one thing is the way you treat everything, so study carefully how to use the moment, before discarding it: “Do not see with ordinary eyes. Do not think with ordinary mind.”

Especially when I began cooking at Tassajara in 1967, using what came to hand was pivotally important. Essentially we had no refrigeration. What we had was old-fashioned insulated walk-ins without any compressors, so we would open the walk-in doors at night to let in the cool air, and then close them in the morning. Menus came from what was in the garden and what was at hand—rather than the fantasy realm of “you can have what you want when you want to have it.” (Yes, and you can lose connection with Source and Sustenance and deplete natural resources relentlessly and unnaturally.)

My next-door neighbors still remember (as do other friends) when I first came to cook at their house, and they exclaimed, “We have nothing to eat.” After I made them a fine meal culled largely from their refrigerator, they said that I should have a TV show called, This Old Food, where I would go to people’s houses and cook what’s there.

So here is a guide to utilizing what can be utilized.

Take a look at what needs to be used. Glean from the garden and keep in mind what’s in the refrigerator. Start with the oldest vegetables before they are “gone.”

When are the vegetables still good? Vegetables are still good up to, but not including, the point at which they become rotten. If parts of the vegetables are still in good shape, the slimy or rotten portions can be removed. Greens are on their way when yellow. These are vegetables at their worst. Before they reach that point they can still go into a bean soup, or perhaps be cooked and blended and then put in soups, or served with a complementary (cover-up) sauce. Vegetables on the edge of oblivion have often been noted to add a marvelous, distinctive taste to casseroles, soups, and mixed vegetable dishes. Play it by nose. I just used some old beet greens (sorted through) with a bit of onion, some chopped olives, balsamic vinegar, and honey. So good. Turning what at first glance appears distasteful into something nourishing.

The next class of vegetables are those wilted or limp from loss of water. These too can still be used. They will need little doctoring other than the addition of some form of liquid—perhaps simply blanching will suffice, or a sauce, a dressing, or a light soup. In this way limp vegetables often make do for nearly any use. Cutting the tops off root vegetables will help keep them firm and fresh.

When vegetables are in their prime, consider doing as little as possible. Consider letting them be what the are—expressing themselves fully—rather than making them into something else. Hopefully, the simple recipes that follow will prove a guide for doing just this.

Of course, once in a while vegetables do become un-eatable. Careful planning and consideration can keep such loss to a minimum, but when it occurs, please give the vegetables back to Mother Earth, via a compost pile. Sometimes, even botched cooking must end up there, but when is a dish really botched? Here’s the recipe for some of the finest greens I ever ate.

Smoked Greens

I don’t necessarily recommend that you try to duplicate this recipe, but maybe you will sometime without even trying. (I did this just the other day, making some smoked lentil soup.)

Greens

Lemon butter

Oil

Salt

We cooked the greens in a wok, the concave Chinese frying pan, over a high flame. They were briefly forgotten about until—“Oh no! They’re burning!” Complete dismay in the kitchen—forty people waiting for supper—what to do to make do? The blackened greens stuck to the bottom of the pan, and out came the rest, to be served with lemon-flavored butter. Everyone wondered, “How did the greens get this wonderful smoked flavor, as though they’d been cooked with a flavorful ham bone?” C’est la vie.

Then all of those blackened leaves had to be cleaned out of the pan.

Carrots

Though common and ordinary, carrots are also versatile, inexpensive, and too often neglected. They can be prepared deliciously by themselves, and add sweetness and color when grated in salads, combined with other vegetables, or added to soups.

Carrots are used here to exemplify several possible vegetable cuts. Any one shape can be done in different sizes. I almost never peel carrots, but scrub them thoroughly and then cut off the stem and root tail—just barely. You needn’t toss away extra half inches of carrots every time you cut. Engage your mind in the activity.

ROUNDS, OVALS, AND JULIENNES

Once you have trimmed off the ends, the cutting can start at either end of the carrot. You can use the tip-of-the-knife-down stroke, slicing down and toward you, or one of the up-and-down chopping cuts (see illustrations in Stroking Down and Toward You and A Third Way to Slice). The latter is particularly effective at the carrot’s thick end. (If you are using a curved chef’s knife rather than the Japanese vegetable knife, you will often find the down-and-away cut useful (see illustrations in Stroking Down and Away from You).

For rounds, the cut is made straight across the carrot, and for ovals the cut is made diagonally across the carrot—keeping the knife in the same position as when cutting straight across, but changing the angle of the carrot (see illustrations).

To make juliennes, I like to cut the carrot into ovals, then cut the ovals crosswise into short julienne pieces. (See below for the more traditional way of cutting julienne pieces or “matchsticks.”)

HALF MOONS

Cut the carrot in half lengthwise. Slice crosswise.

SECTIONS, STRIPS AND MATCHSTICKS

For sections, cut the carrot crosswise at even intervals. Sections can then be cut lengthwise into strips. (The illustration shows how it is sometimes useful to hold the vegetable with your thumbnail while making the necessary cuts.) The strips may be cut lengthwise into short matchsticks. (the illustrations in Stroking Down and Away from You show the tip-on-the-table slice, away and down to cut strips into matchsticks.)

DICING

I like to cut the carrot first into lengthwise slabs, perhaps a quarter of an inch wide. When cutting the carrot lengthwise, you may find it useful to hold the carrot with your left (nonknife hand) thumbnail. Then you can cut lengthwise (about a quarter inch wide) into matchsticks. The matchstick pieces can be diced by cutting them crosswise.

CHINESE ROLLING CUT

Start by making a diagonal cut—cut straight down with the knife nearly parallel to the carrot. Then roll the carrot slightly away from the knife. Make the next diagonal cut at about a forty-five-degree angle to the first cut. After each diagonal cut the carrot is rotated by “walking” your fingertips. The cut surface which was perpendicular to the cutting board, now angles up toward the left. The new cut will intersect the plane of the preceding cut. These pieces can be made large or small, fatter, thinner, longer, shorter, depending on the angle of the carrot in relation with the knife. These pieces are attractive and sauté well, bouncing easily around the skillet, whereas rounds and ovals will often stick together, not allowing for a true sauté.

Carrot Salad

Find out how satisfying carrots can be, salt bringing up the flavors, lemon and honey accentuating their sunny brightness. Green of some sort—say parsley, green onion, or fresh tarragon—would be a welcome complement as well.

Carrots

Salt

Lemon juice

Honey (optional)

Green to garnish (optional)

Wash and grate the carrots, or cut them into ovals and then into thin strips. Sprinkle with salt and squeeze in hands. Add lemon juice and possibly honey. Mix well.

Garnish with green, if you have it and would like.

VARIATIONS

Breakfast Carrots

Just carrots cooked with oil and salt. Without fancy ideas in mind, they taste pretty fine. Good anytime.

Carrots

Oil

Salt

Water or stock with ginger (optional)

Nuts, seeds, or wheat germ (optional)

Wash and slice carrots in rounds or ovals, or use the rolling cut. Stir-fry for 3 to 4 minutes, until the sizzling quiets down. Add some water and grated ginger if using it, put on a close fitting lid and turn the heat down moderately low. Cook about 4 to 6 minutes with the lid on. Are they done? Salt to taste. When the breakfast carrots are ready, you might add toasted nuts or seeds, or maybe wheat germ.

Carrots Sautéed and . . .

Curried with pineapple, banana, or poppy seeds.

Glazed with butter and choice of sweetening.

Seasoned with allspice, caraway, cardamom, cinnamon, cloves, ginger, pepper, basil, mint, parsley, tarragon, or thyme (no, not all of them).

Onions

Onions! Magic beyond compare, especially when sautéed, onions transform the single note melody of other ingredients into full-bodied chords—the flavors broaden and deepen, and you find yourself saying, “Yes, let’s eat.” Onion goes with almost anything including watermelon: it picks up tired dishes, sweetens greens, beefs up sauces, zests salads. But consider who is being served. Raw onion in particular does not suit everyone’s taste. To cope with this I cut the onion pieces very finely—or make pickled onions (which are milder). (And—doctor I am not—onions are not what causes indigestion, though they are fragrant enough to be what you smell when you have it and burp.) The cooking time for onions can vary a lot: a longer cooking will bring out their sweetness and “meatiness”—imagine onion soup! Cooked onions lose their overwhelming sharpness, and become quite compatible with other vegetables. Starting a mixed vegetable sauté with onions brings out the depth of all the flavors excellently.

The fleshy concentric layers of the onion are covered with a skin which is papery and inedible. Like potatoes, onions may be baked in their skins, but usually the onion is peeled prior to cooking or eating. To remove the skins, first trim off both top and bottom ends of the onion. Place the onion on one of its flat surfaces and cut it in half. Peel the layer of papery skin off the onion. If one particular layer shares some fleshy part and some paper part, it’s usually best to remove it entirely, although some smaller paper skin patches may be pared off. Now the onion—halved and peeled—is ready to be sectioned, sliced, diced, minced, or grated.

Crying time. It’ll help to peel all the onions first, and then start cutting, as the cut pieces may then be placed in a covered container off to the side rather than under your nose. Tear remedies include a wooden match between the teeth (OK to chew), and chewing on a piece of raw onion or bread. Many people feel that onion skin is one vegetable trimming which is not especially good in stock.

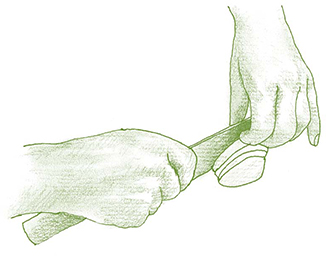

SLICED ONIONS

Place the peeled half onion flat side down, slice (or chop) parallel with the axis (see illustrations in Stroking Down and Toward You, Stroking Down and Away from You, and A Third Way to Slice). When you have sliced about two-thirds of the onion half, tip over the remainder and continue slicing on the uncut surface. A final picture here shows how the remainder of the onion half can be held for the last few cuts, balanced against the first finger and held in place with the thumb. The knife can be guided by the thumb knuckle. This is quite a useful grip to know in cutting many different vegetables—sometimes it will be easier to turn the vegetable around before continuing to cut (cutting radishes into rounds for example), whereas with the onion you can simply tip it over and continue cutting.

DICED ONIONS

To dice the onion, begin with the halved onion, placing it flat side down, root end to the left (if right-handed). Leave the root end intact when cutting. Cut straight down and through, parallel with the axis and at appropriate intervals. Then make a couple of cuts with the knife parallel to the tabletop. Again, leave the left end intact. When cutting horizontally, use a gentle sawing motion so that the knife doesn’t suddenly cut through to your fingers. Now cut straight down across all the cuts you have made. Isn’t it helpful to have pictures? Tip over the intact part. Section it, turn ninety degrees, and dice.

MINCED ONION

To start with, dice the onion as finely as you can. This gives a head start on the mincing.

Sautéed Onions

Sautéed onions are simply classic. I think it was M. F. K. Fisher who remarked that if you’ve been home alone all day and haven’t done much in the realm of house cleaning or laundry washing, have some onions sautéing when your partner comes home, and all will be well. The fragrance in the air says, “Welcome home, honey, you are in for something delicious.”

Onions

Olive oil

Salt

Soy sauce (optional)

Balsamic vinegar (optional)

Slice, dice, or section the onions. Heat a sauté pan, add a thin layer of oil (and a sprinkling of salt), and sauté the onions from 3 to 5 minutes. Allow longer cooking time for bigger onion sections. The onions will first turn translucent, and then begin to brown. (A sprinkling of soy sauce or balsamic vinegar will accentuate the flavors and add to the earthy brownness.)

VARIATIONS

Baked Onions

These come out very sweet, mild, and succulent.

Onions

Balsamic vinegar

Salt

Pepper

Preheat oven to 375°. Bake the onions in their skins like potatoes for 50 to 60 minutes, depending on size. Having a bit of water in the bottom of the pan will make cleaning easier, as the onions release sugary juices which will caramelize in the pan. Onions may also be skinned, then quartered or chunked, and baked in a small amount of water and/or oil. After baking, marinate with some balsamic vinegar, salt, and pepper. As for baking with skins on or off, both have their virtues—partly having to do with presentation.

Green Onions

Known as green onion or scallion, this is the slender long one with a white root end and slightly spreading green top. In most grocery stores these onions will be chopped down to 12 or 15 inches, as the upper greens wilt. All of this onion is good—mild yet zippy. The green as well as the white can be cut finely for salads, or in longer sections for cooking. Particularly when sliced diagonally, the green pieces make an excellent bright green alternative to a parsley garnish. To prepare, first wash, then cut off the roots and break off all wilted green stalks.

SLICING GREEN ONIONS

To slice the onions, grip them with the left hand; thumb and last finger on the sides, then other fingers curled on top. Keeping the tip (or curve) of the knife on the table, the cut is made by pulling the knife down and toward you. (This is the most thorough way to cut green onions.) The table-hugging tip cuts through all of the onion at some point, so that there is no chain of onion slices hung together where they were incompletely cut. Cutting on a long diagonal will make attractive ellipses of green as you see in miso soup in Japanese restaurants. Green onions can be used to decorate and season vegetables, grains, potatoes, eggs, cheese, soups, salads, main dishes—anything. Yes, I’ve even had them finely cut with oranges and watermelon.

Leeks

Leeks, yet another form of onion, look like large scallions. Mild and sweet, they are frequently used in potato soups and quiches. Though some cooks use just the white part as it has a milder flavor, we use the whole plant, prepared and sliced like scallions in narrow slices. The thin slices will make for easier chewing. Before cutting the narrow slices crosswise, I tend to cut the leek lengthwise and then wash out the dirt between the layers. Another option is to wash the slices after you have cut them.

Leeks vary from baby, a fat-pen size (serves two per person), to extra large, an inch and a half in diameter (each one serves 3 to 4 people)—please consider this if you are getting confused about quantities.

Simply Leeks

As the leeks are not cut thinly crosswise here, this preparation is best with tender small leeks rather than the giant 12 to 15 inchers.

Leeks

Butter

Water

Salt

Pepper

Cut off the tips of any wilted leaves, leaving 4 to 6 inches of green. Trim the roots. Cut in half lengthwise and wash between the layers. Melt the butter. Place the leeks flat side down and cook for a couple of minutes. Then add some water (cover the bottom of the pan), salt, and pepper. Cover and simmer for 10 minutes. Check periodically to make sure there is still liquid in the pan. Using a white wine in place of water or adding a touch of lemon juice will enliven the flavors.

Garlic

The subtle, intoxicating, and invigorating flavors of garlic are at their peak when you prepare it freshly—rather than using garlic previously peeled, minced, powdered, or preserved.

MINCING GARLIC

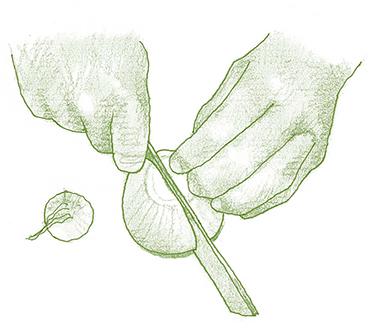

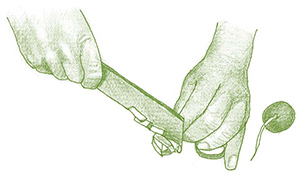

Mincing garlic rates a special note, since it is done so often. I’ve developed a method of mincing the garlic where I rely on my Japanese vegetable-cutting knife. For me, it’s simple and effective, and saves dirtying other implements, such as a garlic press. To use the garlic, separate the cloves from the head. I like to get the peel loose by placing the flat of my knife on the garlic clove and tapping it with the fist of my other hand. Or if the cloves are larger, simply cut them in half lengthwise. Follow this up by removing the papery skins.

The key for mincing garlic is getting it started. On the TV show Yan Can Cook, I think I have seen Martin Yan demonstrate pressing the flat of the knife on the garlic clove and giving it a good wallop with his left hand to smash the clove. Then it can be minced.

I prefer to chop the clove of garlic into thin slices with the back of my knife first, and then mince. People love this method when I demonstrate it. The keys are to hold the knife with the cutting edge directly up (upside down); position the clove of garlic close to the near edge of the cutting board; hold the garlic clove firmly in your left hand; and then, with the back tip of the knife on the counter, lever the back of the knife down onto the clove of garlic, cutting and mashing a section off the edge. Repeat until the clove is “preminced,” then mince it more thoroughly. If this doesn’t work for you, get a garlic press, macerate the clove in a mortar and pestle, or chop it as you please.

Ginger Root

Ginger root is used in several recipes, as it is a pungent bright element much like garlic which can enliven a variety of dishes. I have fabulous bamboo ginger graters, but you can also grate it on a regular cheese grater. In my rustic cuisine, I leave the peel on.

Potatoes

Potatoes are marvelously soft, smooth, filling. Especially after a steady diet of brown rice back in the 1960s at Tassajara, potatoes were always a treat: mellow, earthy, soft. If you want to know how I messed up by serving impenetrable baked potatoes, see “Potato Fiascoes.”

We always eat potatoes with the skins—even mashed potatoes are good with flecks of skin. Scrub before cooking.

CUTTING POTATOES

Cutting into chunks: First cut in half lengthwise. Place these halves cut side down and cut them lengthwise once or twice. Then section the potato crosswise into chunks.

Cutting into rounds: Use the chopping cut, down-and-away continuing down-and-toward. (See the illustration in A Third Way to Slice.)

Cutting into sticks (french fries): First cut into rounds. Then cut the rounds crosswise into sticks.

Home-Fried Potatoes

Simple—and simply delicious.

Potatoes

Butter

Salt

Pepper

Wash the potatoes and cut them into narrow strips, or grate. Smaller pieces will cook more thoroughly and fry more quickly than larger ones. Use a generous amount of butter. Fry on gentle heat, until the potatoes are brown on the outside and soft on the inside (flip or turn over from time to time). Season. The pan can be covered so that the potatoes steam as well as fry. Open and turn over the potatoes regularly. Butter seems to work better than oil for keeping the potatoes from sticking to the pan.

Oven-Fried Potatoes

This is a good recipe to know about. These potatoes can come out well browned without the fuss of french-frying. Works for me—I don’t want big pans of hot oil in my kitchen.

Potatoes

Oil

Salt

Preheat oven to 425°. Cut the potatoes into rounds and the rounds into french-fry shapes. Toss with a bit of oil to coat and then put the sticks on baking sheets, more or less one layer thick. Bake for about 40 minutes. Turn with a spatula 2 or 3 times. Sprinkle with salt. Try one. Bake longer if necessary. These are best when served straight from the oven.

Potato halves can be baked in the same way. Cut in half lengthwise. Place cut side up on baking sheet. Brush with oil, sprinkle with salt, bake. You may also put sliced or grated cheese on top for the last 5 minutes although they are amazingly good when served plain.

Baked Potatoes

Baked potatoes uplift heaven—is that possible? A food of the gods, maybe it’s all the butter and other accompaniments. You’ll have to figure out which of these you’ll want to use, with the list below giving you something of a head start.

Potatoes (russets are the standard for this)

Butter or oil

Accompaniments (see below)

Preheat oven to 375° to 400°. Wash the potatoes, dry them, rub on butter or oil. Bake for an hour or until fork-piercing tender. The bigger the potato the longer the baking time.

Here are some possible accompaniments: Butter, salt, and pepper; grated cheese; sliced green onions; or how about cilantro and salsa? Nut butter or nut butter sauces, sour cream, yogurt, (vegetarian) bacon bits. I don’t know—look in your refrigerator: olives, capers, green goddess dressing, what’s in there?

Mashed Potatoes

The best mashed potatoes bring to mind the sublime—the earth-bound potato raised from the ground to heavenly silky smoothness. Oh let’s . . .

Potatoes

Water

Milk, buttermilk, or sour cream, or rice or soy milk

Butter

Salt

Pepper

Garlic (optional)

Cut the potatoes in halves or thirds and cook them in lightly salted water until tender. Drain off the water and save it for soup. Mash the potatoes, mixing in the milk, buttermilk or sour cream—possibly some butter or a nondairy alternative. Season with salt and pepper. Do you like garlic? It’s fantastic in mashed potatoes.

VARIATIONS

Potato Salads

I suggest dressing potato salads with mayonnaise or with an oil-and-vinegar dressing. Putting on the dressing while the potatoes are still hot helps them soak up all the flavors.

Potatoes

Choice of dressing: oil and vinegar or mayonnaise with mustard, curry, tarragon, and/or marjoram, vinegar and sugar

Choice of vegetables and other ingredients: grated carrot, sliced celery, hard-boiled egg, grated cheese, minced onion, sliced green onion, parsley, black olives, pimento, dill pickle, sliced radishes, fresh basil

Cut the potatoes into cubes and blanch until tender (6 to 8 minutes). Remove and drain. Mix in a liberal amount of dressing, seasoning the dressings to your taste. (You can also look in the section on salad dressings.) Chill the dressed potatoes. Prepare the other ingredients (not too many) and mix them in also. Some of the optional ingredients can be saved for garnishing, especially the grated cheese and the fresh herbs.

Yams and Sweet Potatoes

Even more than potatoes, yams and sweet potatoes are favorites of ours. Deep yellow-orange with sweet, rich flavor, they can be cooked in the same way as potatoes, although the seasoning may vary. In the recipes that follow, the names “yams” and “sweet potatoes” are used interchangeably. (Yams to me have the brick red exterior with the somewhat darker orange-yellow interior. Sweet potatoes have the more beige exterior and somewhat lighter interior.)

Home-Fried Yams (or Sweet Potatoes)

The orange earthiness of the yams is accented with the slightly bitter earthiness of the roasted seeds. Add a touch of orange juice or minced peel to brighten or lift the flavors.

Yams or sweet potatoes, sliced

Oil or butter

Salt or soy sauce

Sunflower or sesame seeds, roasted

Cut and fry these like the regular home fries above. Once the yam slices are soft, add soy sauce and sprinkle generously with roasted sunflower or sesame seeds.

VARIATION

For Onion Home Fries, fry the yams with sliced onions. May be served with yogurt.

Just Yams and More

Yams baked in water have a mellow succulence. Dark greens wilted in butter and/or a salad complement this nicely.

Yams

Water

Salt

Preheat oven to 375°. Scrub the yams, cut in halves or thirds crosswise. Then in quarters lengthwise. Arrange in a baking dish with a quarter inch of water on the bottom. Cover and bake until soft, about 40 minutes.

VARIATIONS

Mashed Yams

These mashed yams can be served on their own or layered in a casserole—see one suggestion below.

Yams

Butter

Orange rind, grated (optional)

Boil or bake the yams. Mash them with butter, salt, and pepper. Mix in the orange rind, and add cinnamon for seasoning. Serve.

VARIATIONS

Sprouts

Sprouts can be started at any time of the year from beans, grains, and assorted seeds, including alfalfa, fenugreek, radish, mustard, sesame and sunflower. The little shoots are literally bursting with energy, as well as vitamins and protein. Crisp with moisture, they are also tender without having to be cut up. Growing them at home, which isn’t difficult, produces the freshest vegetable available.

Most easily sprouted are mung beans (which produce the well-known “Chinese bean sprout”), alfalfa and fenugreek seeds, and lentils. Oats, wheat, and rye are fairly easy to grow, but their taste doesn’t appeal to everyone. Soybeans can be sprouted if the nonsprouting beans are carefully sorted out as the sprouting progresses.

Sprouting seeds need to be kept in a dark, moist, warm environment. First soak the seeds overnight. Drain off the water and reserve it for some other cooking use. Then put the seeds into a wide-mouthed jar. Leave the end open, or cover it with cheesecloth or some other material which lets air in and out. Place the bottle on its side and keep it in a dark, warm place—in a cupboard or simply covered with a towel. To keep the seeds moist, rinse them once a day: cover the seeds with tepid water, swish the water gently around, then pour it through the cheesecloth or into a strainer. If the seeds are actually in water (after the initial soaking) they will tend to rot rather than sprout, so drain off the rinsing liquid thoroughly. Seeds can also be sprouted in a tray, plate, bowl, or crock. Cover with a lid to keep moisture from evaporating. Pour the rinse water off through a strainer. Another method for sprouting is to put paper towels under and over the soaked seeds in the tray. Keep moist and out of the light. This method may take a little longer, but rinsing is not necessary.

Before eating, if the sprouts are put in the sunlight for several hours, they will turn green, which means that chlorophyll and vitamin C are present.

Seeds take from three to five days to sprout. Alfalfa sprouts are at the peak of their nutritional value when they are one inch long, but they can be eaten when they’re several inches long, and even after the first leaves appear—“alfalfa lettuce.”

Lentil sprouts peak at two inches, soy and mung bean sprouts at three inches.

Homegrown mung bean sprouts are darker than the commercial variety, which are chemically bleached.

For eating, grain sprouts are best when equal in length with the grain. Larger grain sprouts can be chopped or used in breads.

If the seeds don’t sprout, it may be that the particular batch of seeds is old, defective or sprayed.

Sprouts are tasty and refreshing when eaten raw. They can be added to any salad, centered in a clump or tossed in with everything else. They also add a moist, light quality to sandwiches. Only bean sprouts are really suited to cooking. The others, being very delicate, can stand only brief cooking—add them at the end—in the last two minutes for soup or as a garnish for soups or mixed vegetable dishes.

ALFALFA SPROUTS

Very popular in salads and sandwiches, these make an excellent side dish as well. Lemon juice sweetened with honey dresses them adequately.

Alfalfa-Banana Sprouts with Nuts

If you’re looking for a more substantial side dish or salad, try this.

Alfalfa sprouts

Banana

Lemon juice (optional)

Walnuts

Mash the banana to make a dressing for the alfalfa sprouts. Thin and season with lemon juice if necessary, then mix it with the sprouts and walnut pieces (which could be roasted).

VARIATIONS

Stir-Fried Bean Sprouts

A straight-forward dish with optional seasonings in the variations.

Bean sprouts

Celery

Mushrooms

Oil

Water or stock

Salt

Soy sauce

Slice the celery and the mushrooms. Stir-fry them in oil for about 2 minutes before adding the sprouts. Stir to mix, add some water or stock and a bit of soy sauce. Cover and steam a couple of minutes. Adjust seasoning and serve.

VARIATIONS

LENTIL SPROUTS

For a two month period during one winter several years ago the fourteen-mile dirt road into Tassajara was washed out (see “Finding Out That Food is Precious”). That provided quite an incentive to conserve food and to use things efficiently. Everything was at a premium. That’s when we first started sprouting seeds. Two cups of lentils became over a gallon of sprouts. We had them almost every day for lunch, by themselves or mixed with wild greens: curly dock, miner’s lettuce, chickweed, shepherd’s purse. Arugula or a baby lettuce mix would be excellent alternatives. Equal amounts of vinegar and honey dressed the salads, except on occasion when a few lemons or oranges would show up. Living with some limitation like that, everything was delicious. Maybe with other things available lentil sprouts aren’t quite that good, but I am still fond of them.

Lentil sprouts, somewhat heftier than mung bean sprouts, may require slightly longer cooking, but the same recipes can be followed. One combination to try is with onions and roasted sunflower seeds, seasoned with soy sauce and ginger.

Cabbage

Like any vegetable, cabbage is what you make it. Don’t boil it down to mush and don’t serve it with overly sweet mayonnaise. When raw, I find it best sliced quite thinly and given a little salt to start with. Cooked, it is good sautéed or lightly steamed. Raw cabbage has a natural peppery or slightly hot taste, which is vigorous and refreshing, that can be accented with the seasoning. Red cabbage is somewhat more pungent than green, and lends coloring to green salads or mixed vegetable dishes. Chinese cabbage (also known as hakusai, or nappa) has a very mild flavor and is quite juicy and tender—a marvelous ingredient for a fresh-tasting salad.

CUTTING CABBAGE

To prepare, remove the outer wilted or dirty leaves. Wash these and use them for stock, or if in good shape cut and prepare with the remainder of the cabbage. To slice the cabbage, first cut it in quarters lengthwise through the core. Holding the quarter at an angle with the cut surfaces facing up, cut out the core.

Remove a few inner layers of the cabbage, place them flat on the table, and then slice thinly crosswise. Place the remainder of the cabbage leaves on the counter—I often do it in two batches—inner side down (to help flatten it out), and slice thinly crosswise. If necessary to have the cabbage leaves lay flat, cut them in half crosswise first, and then place the inner side down and slice thinly. Cut into larger wedges or cubes for steaming or soups.

Thin-Slice Cabbage Salad

Can you cut the cabbage as thin as you can without cutting yourself or taking forever? This is what makes the dish. So simple, so delicious.

Cabbage

Salt

Honey or sugar

Vinegar or lemon juice

Cut the cabbage in thin slices. If you have some question about how to do this, see the above instructions for cutting. Sprinkle with a couple pinches of salt and squeeze in your hands, this way and that, until some moisture begins to come out of the cabbage. If this isn’t happening after a minute or so, add a little more salt and work it some more. Add sweet (honey, sugar) and sour (vinegar, lemon juice) to brighten the flavors. Taste before and after the addition to notice the difference.

VARIATIONS

Sautéed Cabbage

For my taste a very light cooking leaves the cabbage perky and live-tasting. See what you discover.

Cabbage

Oil

Salt

Water

Cut the cabbage fairly thinly. Stir-fry a couple of minutes until the cabbage wilts slightly. Add some water (or white wine) along with a little salt, put on a lid, and steam briefly.

VARIATIONS

Tomato-Sautéed Cabbage

Food is so delicious, especially when you haven’t filled up on chips and dip. Take this dish with cabbage brought more fully alive with the red summery fruit of tomato, the grassy green pungency of the onion or parsley. Cook it a short time and the tomato pieces will retain their shape and fresh-flavor. Cook it longer and you will have cabbage with tomato sauce—you may want to add some dried herbs (especially thyme and oregano)!

Cabbage

Tomato

Green onion or parsley

Oil

Salt

Slice the cabbage into about 1-inch squares. Section the tomatoes and slice the green onions. Stir-fry the cabbage for 3 or 4 minutes, add the onions and tomatoes (along with a little salt), cover, and cook just a couple of minutes, until the tomatoes are hot.

Red Cabbage and Apple

This is more or less a traditional Northern European dish, that here is prepared without the meat juices.

Red cabbage

Apples

Brown sugar

Vinegar

Salt

Pepper

Cut the cabbage into fairly large wedges. Slice the apples. Sauté the cabbage for several minutes before adding the apples. Then sprinkle on equal amounts of brown sugar and cider vinegar, making it sweet and sour to taste. Salt and pepper lightly. Cover, cook for 5 to 8 minutes, and serve.

VARIATION

Bake in a covered baking dish for 30 minutes or more at 375°. You may want to try adding a sprinkling of sherry to sooth its nerves. When baked the dish will be quite a bit limper than the unbaked version.

Celery

Celery is notably stringy, crunchy, crisp, but it can also be a tender and luscious green with no strings attached. Used primarily as an accompaniment, celery attractively greens and complements cauliflower, potatoes, squashes, soups, casseroles, and salads. But like carrots and onions, celery can also be a main ingredient. Celery leaves are very much edible and, when finely chopped like parsley, add seasoning. Especially in salads, celery is best when cut thinly, prettiest when cut in boomerang shape. The thinner the celery is cut, the less string there is and the more easily it is chewed.

CUTTING CELERY

To prepare the celery, break off individual stalks and wash them carefully, rubbing thumbs up and down the interior surfaces. Place celery stalk with leaf end to the right and cut off side branches. (Chop these separately.) Turn bottom end to right and trim off the end of stalks. When you cut the celery into thin slices, the strings of the celery stalks are cut into short pieces as well, which make the celery easy to chew. Here are two ways to do it.

To cut boomerang pieces: Hold the stalk (or stalks) on its edge and cut on a diagonal.

To cut comma pieces: Let the stalk (or stalks) lie flat and cut on a diagonal.

Orange-Celery Salad

What makes this salad exquisite for me is slicing the celery thinly into beautiful shapes. (See above.) Then the vibrant stalkiness of the celery lends a touch of ground to the fruit—while still being easily chewable: flash of color, flash of flavor.

Celery

Oranges

Apple

Salt

Honey (optional)

Lemon juice (optional)

Spearmint leaves (optional)

Wash the celery and trim off the leaves. Hold the stalks on their edges and cut into thin pieces diagonally. Add salt lightly. Cut the peel off of the orange and cut in rounds or half rounds. Wash and quarter the apple. Cut out the seeds, and cut in slices. Mix all together. Need anything else? (You may enjoy some honey and lemon juice for instance, or some spearmint leaves.) Sprinkle chopped celery leaves on top.

Quick-Fry Celery

A quick sauté will do wonders for most any vegetable. Celery is no exception—so go ahead and surprise yourself with how good this is. Splurge with some gratings of fresh black pepper.

Celery

Oil

Salt or soy sauce

Slice the celery and stir-fry in oil (and salt) until tender. Sprinkle on some soy sauce, if you’d like a different sense of salt.

“Fancy” Boiled Celery

What makes this “fancy” is the use of butter and cream. If you are not eating dairy, I would suggest the options of roasted cashews or cashew butter thinned with water.

Celery

Butter

Cream or milk

Salt

Pepper

Cut the celery in boomerangs. Boil in a covered pot with just enough water to cover the celery. When tender, pour off the water and save for stock. Then add a touch of butter and cream or milk, along with salt and pepper to taste.

Mushrooms

Mushrooms aren’t really vegetables, of course, they’re fungi, which grow from rot—turning it into something edible. Some mushrooms, shiitake for one, are considered to do the same in the body, reducing cancerous growths. I think most vegetarians must grow to love mushrooms, especially if they were once meat eaters, as mushrooms have something of a meaty quality: dried mushrooms in particular have something of the chewiness of meat.

Nowadays there are many mushrooms readily available: most commonly the generic whites, the brown field mushrooms, fresh shiitakes, and portobellos. As with other ingredients, I tend to keep it simple—I have neither the cabinetry for storage nor the wherewithal to track everything—so I mostly stick to the brown field mushrooms and the fresh shiitakes.

The price per pound for mushrooms looks high, but there are a lot of mushrooms per pound and, like garlic, a little can go a long way. A few mushrooms can be a good addition to almost any vegetable dish. I think I’ve had mushrooms with every vegetable except beets. Plus, there are mushroom sauces, mushroom soups, mushroom stuffings, and mushrooms stuffed.

Mushroom lovers insist that mushrooms not be washed—especially the wild ones—but, if anything, simply wiped with a damp towel. Still, I prefer to give them a quick bath, lightly rubbing the tops with my thumbs. (I like to determine these things from my own experience, and hey, I’ve done taste tests and can’t say that I notice a distinctive taste difference between the washed and the wiped. Appearance-wise, the wiped-by-hand ones definitely look more attractive. Go figure—or observe for yourself.)

Mushrooms can be sliced using the chopping cut, down and slightly toward. If the stems have darkened with age, they can be trimmed off and discarded. (The stems of fresh shiitakes need to be cut off and discarded as they are not chewable.)

Mushrooms don’t require much cooking. They brown in just three to four minutes and steam to perfection in five minutes. When added to soups at the last minute they bob handsomely on the surface. Mixed into potato dishes, grain dishes, stuffings, or casseroles, the mushrooms can cook for a more lengthy time and their flavors will permeate the dish.

Mushroom sauce can be made by adding sautéed mushroom slices to a white or brown sauce. Mushroom soup can be made by thinning the mushroom sauce with hot milk to soup consistency.

Sautéed Mushrooms

Sautéed mushrooms can be served on their own or used to garnish other vegetable dishes. They can also be added to grain, bread cube, or potato stuffings. The hearty flavors and deep brown colors can make this a striking accompaniment, so give it a consideration when otherwise at a loss of what else will complete a meal.

Mushrooms

Oil or butter

Salt

Pepper

Parsley, minced or green onion, finely sliced (optional)

Slice or quarter the mushrooms. Cook them in butter or oil, 3 to 4 minutes. Season with salt and pepper. Sprinkle with minced parsley or green onion.

VARIATIONS

ABOUT DRIED MUSHROOMS

I have found dried mushrooms available at Italian groceries (porcinis) and at Asian food shops (shiitakes). Both are prepared in the same way by soaking for thirty minutes or more in warm or hot water.

Be sure to save the water in which the mushrooms were soaked. There will be some dirt at the bottom of the soaking bowl, so after removing the mushrooms, carefully pour off the liquid or strain it through a paper towel. This soaking liquid will be a flavorful addition to the dried mushroom dish itself, or to some other soup, sauce, grain, or casserole dish. After soaking, the mushrooms can be used whole or sliced. The Asian type can be cooked in ten minutes, while the European type takes twenty minutes or more. Simmer them in the soaking liquid or a sauce. They are a great addition to sauces and soups both for flavor and texture. They are also good in quiche or lasagna.

Parsley

Parsley can be used as an ingredient, a seasoning, or a garnish. It is excellent in soups, especially those which seem overly sweet, like onion, carrot, or yam, as it provides a lemony grassiness that fine tunes the flavors. Parsley sprigs are a famed and overused garnish. Green onion, water cress, green pepper, celery, cucumber, and alfalfa sprouts, artfully sliced and arranged, could all be considered alternatives. Flat-leafed (Italian) parsley has a great flavor and is easier to work with than the curly leaf. I recommend it.

MINCING

The parsley (or whatever vegetable is to be minced) is first cut as finely as possible right from the start. With parsley, several sprigs can be bunched together. Roll the sprigs up sideways to clump the leaves into a more cutable pile—then it’s helpful to cut off the loose ends and place the main pile on top of them—and then cut finely crosswise. Again the sides are held in with the thumb and little finger, the other fingers bunching together the top. The short down and away cut can be very effective here. If you can do this well, it will take care of the mincing. Otherwise proceed to the second part.

The finely cut pieces may be piled up to be minced. If a curving chef’s knife is used, the knife is rocked up and down through the pile. The top edge of the blade is tilted in the direction in which the knife is traveling. Each chop is farther and farther away, or closer and closer, to the person chopping. At intervals the dispersed pile is regrouped for further mincing. If a straight-edged Japanese vegetable knife is used, the tip can be held down with thumb and first finger on either side of the blade (or between first two fingers with the thumb on top—see also mincing and mincing garlic).

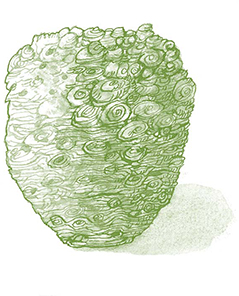

Winter Squash

Winter squashes are harvested in the fall and, if their tough outer skin is intact, they will keep for several weeks or more over the winter. They include banana squash, Hubbard squash, acorn squash, butternut squash, even pumpkin, which makes heartwarming soup and vegetable dishes as well as pie. Smooth, squashy, and among the most satisfying of wintertime foods, when cooked, these vegetables are like a piece of summer sunshine. They are usually steamed or baked, or a combination of both. If the skin is tough, the squash can be eaten by scooping out the pulp with a spoon. Thinner skins can be eaten. Another alternative is to cut off the skins before or after cooking.

Steamed Winter Squash

Steaming the winter squash brings out its mild mellow goodness. The butter or nut butter gives it richness.

Squash

Salt

Water

Butter (optional)

Nut Butter (optional)

Put about ½ inch of water in the bottom of a pan. Cut open the squash, remove the seeds and cut into serving-size chunks before putting it in the water. Sprinkle on some salt, heat to boiling, then turn down to simmer. Put on a lid and let cook until tender, about 30 to 40 minutes. Serve with melted butter, or mix some of the cooking liquid in with a nut butter, season, and use it as a sauce. A green garnish would provide color and freshness.

Roasted Winter Squash

Roasting the squash will give it a more robust nutty earthiness. Use the spices and it’s almost dessert.

Squash

Oil or butter

Salt or sesame salt

Cinnamon, nutmeg, or allspice (optional)

Preheat oven to 375°. Cut up the squash, remove the seeds, and arrange the pieces in a baking dish. Baste the pieces generously with oil or melted butter; add cinnamon, nutmeg, or allspice to the basting liquid, if you like. Bake for 40 to 60 minutes, depending on the size of the pieces. Baste every 10 or 15 minutes for added moistness and flavor. Season with salt or serve with sesame salt.

VARIATIONS

Beets

Beets are red, and once they are cut open or cooked, beets will tint everything that comes into contact with them—hands, knife, cutting board; egg whites and potatoes turn pink; even celery and carrots will redden with prolonged contact—a wondrous effect.

Beets have a sweet, earthy flavor, and cooking will bring out their sweetness. Raw beets are occasionally eaten grated in salad. They taste, quite simply, like dirt, which may not be so bad, but I prefer to cook them first and then grate them. Beet greens, including the red stems, are quite edible, tender, and mild tasting. They can be cooked with the beets or separately as a greens dish. A pound of beets without tops can provide four servings. (In fact this is my standard measure for determining quantities: four ounces of vegetable per person.)

COOKING BEETS

Boiling is the most common method of cooking beets, after which they may be prepared as a beet dish or combined with other ingredients. Scrub the beets as best you can with the root and about one inch of stem attached. Cover or half-cover the beets with salted water, then cover with a lid and simmer until fork-piercing tender—one-half hour or more for smaller beets, up to an hour or more for larger ones. Check from time to time that there is still water in the cooking pot. (Seriously—I have more than once found the beet pot without water.) With a pressure cooker, use just an inch of water and cook twelve to eighteen minutes, depending on size.

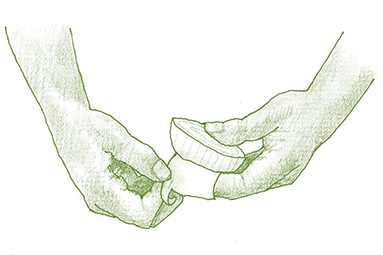

When the beets are drained and cool enough to handle, one of the most sensuous pleasures in cooking awaits: slipping off the skins. A gentle tug dislodges the stems, then, squeezing the beet proper, out pops the bright interior—smooth, slippery, warm, and plump in your hand.

Next, cut the beets in the desired shape: rounds, half rounds, wedges, quarters, or eighths. Notice I do not say cubes: I am not a fan of making beets look like they came out of a machine.

Then, reheat the cut beets with a bit of butter, salt, and pepper. Beyond this you might do the following:

Beets can also be steamed. Cut the stems off about an inch from the beets, then the beet juices will stay inside the beet, and you will have a little handle to start the skin removal later. If they are fresh and in good condition, you can save the the greens to cook later (one recipe here calls for them), but they can also be added to other vegetable dishes or soups, like spinach or chard.

Put the beets in a saucepot with one-half inch or so of water; it doesn’t need to cover the beets. Cover the pot and heat to boiling, then reduce the heat and continue cooking (steaming) until the beets are fork-tender. This will take about thirty minutes, depending on the size of the beets. If the biggest ones are cut in half, they will cook more quickly. Check the pot on occasion to make sure it still has water in it.

Remove the beets from the pot or pan and let them cool for several minutes until you can handle them easily. Remove the stems, and then slip off the skins by hand, as above.

Cut into the desired shape.

Baking the beets will give them a somewhat sweeter, roasted, or grilled flavor. Prepare the beets as for boiling, leaving on the root and an inch of stem. For larger beets, slice into halves or quarters through the stem and root. Toss with olive oil and sprinkle with salt and pepper. Bake at 375° for one half to one hour. Season to taste, sprinkle with balsamic vinegar if you like, and serve. Roast on kitchen parchment to keep the pan cleaner.

Another alternative would be to put the unpeeled beets (with the inch of stalk) in a baking pan with one-half inch of water, and cover with foil or a lid. Bake at 375° until fork-tender, about one hour. As with the steamed beets, wait for them to cool before peeling. Season to taste and sprinkle with balsamic vinegar.

Beets and Greens

I usually find the idea of washing and cutting up the greens for this dish to be somewhat daunting, but the dish speaks for itself: the beets gentled by the greens, the greens made more sturdy by the beets.

Beets

Beet greens

Salt

Pepper, black or red

Green onions or chives (optional)

Boil or steam the beets and cut them as described previously. Cut the greens and stems into 1-inch sections crosswise (and wash). When reheating the cooked beets, add the greens, and a little salt along with some pepper, cover and steam for a couple of minutes. Then stir the beets and greens together, adjust the seasoning, and continue cooking until done—another 2 or 3 minutes. Garnish with sliced green onions or chives.

VARIATIONS

Radishes

Radishes have a snappy, peppery flavor which is refreshing and palate cleansing. Aside from being served whole, as an appetizer with sweet butter and salt, radishes can be sliced and added to salads: lettuce, cabbage, potato, bean, vegetable, corn. Some people find it is easier to leave the stem and leaves attached when slicing so there is something to hold on to. But after a few slices you can turn the radish around and hold it with your thumbnail. If you want red-tipped radish juliennes, cut into rounds, then cut the rounds crosswise. Another possibility would be to cut the radish using the Chinese rolling cut.

The white radish, known as icicle radish or daikon radish, has a hot taste, so it may be quite a hit in salads, or again it can be cooked like carrots, to make the flavors milder.

Radish Salad

The fresh goodness of earth, water, sunlight, and sky brought to the table.

Radishes, sliced

Green pepper, slivered

Carrot, grated

Vinegar

Soy sauce

Honey or sugar

Sweeten the vinegar to taste with the honey or sugar and season with soy sauce. Mix with the vegetables.

Radish-Raisin Salad

The sweetness of the raisins with the pungent flavor of the radishes.

Radishes

Carrot

Lettuce leaves (or arugula)

Raisins

Oil

Vinegar

Soy sauce

Mint, fresh basil, or flat-leafed parsley (optional)

Slice the radishes in rounds. Cut the carrot into short matchstick pieces. Tear or cut the lettuce into small pieces. Mix up the dressing—about 2 parts oil and 1 part vinegar and then soy sauce to taste. Toss everything together. And splurge: garnish with cute little leaves of mint, fresh basil, or flat-leafed parsley.

Turnips & Rutabagas

Is it ruta-BAH-gas or ruta-BAY-gas? They’re good either way. Turnips and rutabagas are both root vegetables: the turnip round and white, often with a purplish area on its skin; the rutabaga more oval shaped and orange-brown. When eaten raw they have, as radishes have, something of a peppery, zesty taste. When cooked just to tenderness, their taste is clean, mild, with a slight bite. Cooking to mushiness will draw out the more odorous and penetrating flavors, which is OK, but like well-cooked cabbage, it is not a taste everyone acquires. Here are several ways to prepare them.

Turnip Pickle

This is a Japanese-style pickle, originally made with seaweed.

Turnips

Salt

Lemon peel and juice

Sugar or honey

Kombu seaweed (optional)

Much like the Thin-Slice Cabbage Salad, here’s another recipe that will test how well you’re cutting. Wash the turnip and trim off the root and the green at the top. Cut the turnip in rounds as thin as you possibly can. Half rounds won’t have the same wholeness, but they’ll do, as far as flavor. Put the slices in a bowl with some salt (about ¼ teaspoon for each medium sized turnip), and salt under pressure (see Salting Vegetables) for 30 minutes or more. (It can even be overnight.) Meanwhile, peel a lemon with a vegetable peeler and cut the strips of peel into ¼-inch squares or narrow crosswise strips. Soak the kombu for 20 minutes and cut it in ¼-inch squares also. If there is a lot of water with the turnips after salting, pour it off and save it for some soup stock. Taste the turnips and rinse off any excess salt. Mix the lemon juice with the sugar or honey to taste, and then toss everything together. The turnip is good by itself after just the salt and the pressing, too. The pickles will keep.

Turnip Stir-Fry

A natural for those littleish turnips which come with a lot of green.

Turnips

Turnip greens

Olive oil

Salt

Pepper

Ginger, freshly grated

Sugar (optional)

Wash the turnips, then cut in half and slice. Wash the greens, cut in 1-inch sections, and keep them separate from the turnips. Stir-fry the turnips for 3 or 4 minutes in the olive oil. Turn the heat down to medium low, put in the greens, along with the salt, pepper, ginger, and possibly a couple pinches of sugar, and cover. Let it cook for 4 or 5 minutes. Check it once in the meantime. Is it doing OK? Temperature all right? Turnips not quite tender?

VARIATIONS

Roasted Turnips or Rutabagas

Roasting the turnips or rutabagas does wonders for deepening their flavors, giving them a sense of nuttiness, that you could enhance with some roasted, chopped almonds.

Turnips and/or rutabagas

Olive oil or butter

Balsamic vinegar (optional)

Preheat oven to 375°. Wash the vegetables and cut them into ½-inch chunks. Toss with oil or melted butter. Place on baking sheet or pan and bake for about 40 minutes. May be garnished with grated cheese and/or chopped parsley when serving—or the roasted, chopped almonds as mentioned above. A sprinkling of balsamic vinegar brightens the flavors.

Greens

This is mainly about chard and spinach, probably the two commonest greens, but what is written here can be applied to most cooking greens. Beet greens (one of the most tender), turnip greens, collard and mustard greens, kale (probably the toughest green) and bok choy are all frequently available. Of these, only spinach is really appetizing when eaten raw, although the others may be thinly sliced and salted as a thin-slice salad.

Greens are slightly bitter or tart, but other flavors can be brought out depending on the way they are prepared. When using greens, the first decision is how much of the stems to use. With chard I like to cut out the stems using a V cut, and then cut them thinly crosswise about a quarter of an inch wide. With kale, collards, and mustard greens I tend to cut off the fat part of the stems and discard them—or use them to make stock. To cut the leaves I often start by cutting them in half lengthwise, then piling them up and cutting them crosswise into one-inch pieces.

Greens cook down by quite a lot, so to come out with the same cooked volume as with other vegetables, it is necessary to start with three to four times as much raw volume. We have found, however, that people eat about the same amount, by weight, of greens as they would of other vegetables.

When doing a combination vegetable dish with greens, the other vegetables can be stir-fried in the bottom of a larger pot. Then there is plenty of room to add the greens for steaming on top of the other vegetables. Folding over the stir-fried vegetables from the bottom will speed the process.

CHARD AND SPINACH

Spinach greens add a tender meatiness to salads, while chard is tougher and tends to pucker the mouth when eaten raw. Spinach leaves have (mostly) thin, easy-chewing stems, while chard leaves are centered on a broad, stringy white stalk. There is also a spectacularly beautiful chard with leaves centered on a red stalk with red ribs extending out into the green leafiness and also yellow chard. If prepared by themselves, these greens are probably best steamed or sautéed. Often slightly bitter, all greens can be sweetened when cooked in combination with onions, carrots, bananas, or such, and can be a main dish when cooked with eggs.

Nowadays baby spinach is often available in the produce section, and makes excellent spinach salad. Otherwise the stems of the largest spinach leaves can be removed, and the larger leaves cut into smaller pieces. Used in combination with other salad greens, or used alone, spinach may want a creamy dressing, perhaps some chopped hard-boiled egg, or maybe some grated cheese. Minced onion is good, too, if you and your guests think so. Little chunks of tomato make a bright addition; sliced pear or apple are complementary and refreshing. Roasted, sliced almonds add a welcome earthiness. I also enjoy spinach salads “wilted” with hot oil.

Steamed Whole Spinach

Spinach is particularly elegant and tasty cooked this way. The funny thing is that most people don’t know what it is. I have heard people commenting, “Oh my, how gorgeous—what is it?” One time someone said, “I think maybe it’s dandelion leaves.” For such a simple dish the reactions are often astounding. What makes the dish is some careful attention to details.

Spinach

Salt

Melted butter

Lemon wedges

Wash the spinach and, as you do so, make an effort to keep all of the stems going in the same direction. Arrange the spinach in a steamer, again in piles of leaves with stems in the same direction. Sprinkle in a little salt, picking up piles of leaves here and there. Steam the spinach just 2 to 4 minutes. Arrange the spinach attractively with lemon wedges (an extra star if you’ve taken the seeds out) on a heated serving platter. Spoon some melted butter over the spinach. Serve immediately.

VARIATION

Steam the spinach in a small amount of melted butter with a lid over the pot—the liquid released from the spinach as it cooks will keep it moist.

Sauté-Steaming Greens

Ease of cuisine, that’s one of the goals here. Start the greens cooking in the oil, then season and cover to complete the cooking. Black or red pepper, or green chilies, garlic or ginger, vinegars of various flavors (or lemon or lime juice), and soon you have numerous dishes at your command.

Greens

Olive oil

Salt

Pepper, black or red, or minced green chilies

Garlic or ginger (optional)

Lemon juice or vinegar

Once the greens are washed and cut, start the stems cooking in some olive oil (if you are using them). After 1 or 2 minutes begin adding greens, and continue adding as the greens cook down. Sprinkle new additions with some salt and black or red pepper (or other pungent ingredient). Cover and turn the heat down to finish cooking by steaming. Add a bit of lemon juice or vinegar to brighten the flavors.

Greens, Orange and Onion

Once again, steamed greens—only on a bed of carrot and onion, which add a marvelous earthy sweetness to the greens.

Greens

Onion

Carrot

Oil

Salt

Lemon juice (optional)

Wash the greens and cut them in 1- or 2-inch sections. Slice the onion and cut the carrot into small pieces. Sauté the onion for 1 minute, then add stalk pieces and the carrot, continuing to sauté for 3 to 5 minutes. Turn the heat down and add the greens, or as much as will fit comfortably. Sprinkle with salt. Cover and let steam for 1 minute, then open, fold in the greens, adding the rest if they didn’t fit at first. Steam another 2 or 3 minutes. Add lemon juice, if you have it.

Greens Get Egged On

The egg can appear or disappear, but in any case the greens become more meaty.

Greens

Olive oil

Salt

Pepper

Eggs

Soy sauce (optional)

Onion or green onion (optional)

Sauté-steam the greens until they’re nearly done. Stir in some beaten egg or eggs. With few eggs and lots of stirring, the eggs will blend in much like a seasoning. With more eggs and less stirring, the effect will be more omelet-like. A little bit of soy sauce can season the eggs. If you like onions, start by sautéing the yellow kind before adding the greens, or sprinkle on some chopped green onion to finish.

Lettuce: Head, Romaine, Boston, Oak Leaf, Red Leaf, Butter

Lettuces includes a wide variety of tender, leafy greens. Head lettuce and romaine are two with crispy-crunchy leaves, while the others tend to have softer, more velvety leaves. There are many exacting prescriptions for turning lettuce into salad. What follows are some basic principles.

Remembering that the idea is to eat some lettuce, why not just rinse off the earth and serve it? If you appreciate and enjoy lettuce like this, and the other people eating do also, read no further, nothing could be simpler. When one is in the garden this is sweet, savory, redolent eating. In the kitchen though maybe adding a little salt would bring out the flavors. What happens when salt is added is that water is drawn out of the lettuce. It goes limp, loses its crisp. With cabbage this is appropriate, but lettuce leaves, more delicate than cabbage, don’t have crisp to spare. The answer to this is get the lettuce coated with oil first (the oil also helps with “mouth-feel”). The salt won’t penetrate nearly as fast—and the oil helps the salt stick to the lettuce. Now the lettuce is rather gummed up with oil. What cuts oil is vinegar. A bit of zing, too, not bad. So that’s the basic dressing: oil, vinegar, and salt. Beyond this basic dressing, we can explore ways to further amplify, mollify, pacify. More about that in the salad section. For now let’s take care of the lettuce.

WASHING AND DRYING LETTUCE

Dirt is one of the most unappetizing things that could garnish lettuce. It adds a lot of hesitation and reluctance to chewing. Often only the outer leaves of a head of lettuce need washing—these leaves will frequently have some dirt tucked away in their folds or at the base of their stalks, but it is most practical to simply rinse off all the leaves. Focus some attention and energy on the activity of washing, and it can be a blessing.

It is sometimes recommended to wash each leaf individually under running water, since soaking the lettuce in water will leech out flavor and nutrients. I’ve never found that this running water method works very well, and it is impractical in any quantity—as well as a waste of water.

Here’s what I have found:

Prep the lettuce some before washing. Remove any wilted, yellowed, or slimy leaves and discard. Cut or tear the lettuce into bite-sized pieces. I did say “cut or tear.” Somehow people still think that cutting lettuce is damaging to the flavor—I haven’t noticed this—especially now that kitchen knives are made to not react with the food being cut. But I have noticed that people take a number of leaves at a time and rip the lettuce to shreds (often misshapen pieces) and call it “tearing”—not appetizing in my experience. Not good for the lettuce or its appearance.

Here’s my suggestion:

With romaine lettuce, cut it lengthwise down the rib, and for the largest leaves cut each half again in half lengthwise. Then cut all the leaves crosswise into one-inch pieces. Simple. Elegant. It works.

With other leaf lettuce, make a short lengthwise cut in the stems before tearing the leaves—and I do suggest tearing one leaf at a time. (As with so many kitchen practices, you can always study for yourself what works best for you.) The smaller leaves may be left whole.

Prepping the lettuce before washing makes it easier to clean—and also to dry.

To wash the lettuce immerse it in water. Swish it around and remove to a salad spinner or colander. Spin it dry in the salad spinner—or what I do for myself when I’m without a spinner, place in a clean dishtowel, hold the corners together and twirl outside. (For larger quantities you’ll need an old onion sack. At Tassajara we used an old dryer—on spin without heat. And nowadays you can also purchase a big-bucks “greens machine” for spinning greens or drying off french fries which have been soaking in water prior to frying.)

You can keep the dried lettuce in the refrigerator, covered with a damp towel. But of course the flavors are better when the lettuce is closer to room temperature. Go figure.

Here are some alternatives for dressing a salad.

Two-Step Salad Toss

A simple way to dress a salad on a day to day basis.

Olive or other salad oil

Vinegar or lemon juice

Salt

Pepper

Herbs of your choice (optional)

First toss the salad with oil. Start with a small amount, toss well, and see that each leaf has got some. When the salad is sufficiently oiled, sprinkle on your choice of vinegar or lemon juice, salt, freshly ground pepper, and perhaps dust with herbs, all just to your taste. Toss well. Done properly, there won’t be a puddle of dressing on the bottom of the salad bowl or plate, and the dressing will give a little kick without being overpowering.

VARIATIONS

Lemonade Lettuce

This makes a light, refreshing salad. Maybe a bit unusual at first, but the sweetened, fragrant lemon leads right into the lettuce-ness of lettuce.

Lettuce

Lemon juice

Honey

Salt (optional)

Sweeten the lemon juice to taste. Mix thoroughly. Dip a piece of lettuce in it to sample. This is a wonderful dressing for wild, edible greens such as miner’s lettuce, chick weed, shepherd’s purse and curly dock. It can also be made with vinegar and sugar. Add a touch of salt possibly. Toss first with olive oil if you wish.

Nut-Butter Dressing

The earthy oily nut quality can be a grounding element with leafy greens, especially the more sturdy ones, such as spinach, cabbage, and kale. With more delicate lettuces adding toasted nuts or seeds directly seems a useful alternative.

Nut butter

Water or oil

Vinegar

Honey, sugar, or maple syrup

Salt or soy sauce

Pepper, black or red

Thin out the nut butter with some warm water (or possibly some oil). Season to taste with vinegar, sweetening, salt or soy sauce. Spice it up with some pepper (black or red) or some fresh ginger. Thin more to desired consistency. Yum . . .

Artichokes

Artichokes are one of the most spectacular and aristocratic of vegetables, despite (or maybe because of) the fact that most of it is thrown away. A type of thistle, artichokes are grown in California in an area centering around Castroville, the “artichoke capital of the world.” Artichokes are served whole and the leaves pulled off at the table, dipped in melted butter or sauce, and the fleshy end bitten off. If the artichokes are small, the outer leaves can be removed and the inner portion cooked and served as an “artichoke heart” where the whole thing is eaten—these also come in jars prepickled for use in salads. Whole artichokes are usually boiled or steamed (occasionally baked), while the hearts can also be sautéed, deep-fried, or pickled for salads. Artichokes are not eaten raw, but may be served either hot or cold.

To wash artichokes, hold them by the stem and swish them briskly up and down in water. Some of the tougher outer leaves may be removed. Cut off the stem flush with the lower leaves. The artichokes can be cooked like this or the top one-quarter to one-third of the leaves may be cut off with knife or scissors. (This removes the thistles which are at the end of each leaf, so that eating the artichoke is easier.) The stem, when peeled, may be cooked and eaten along with the rest.

COOKING ARTICHOKES

Artichokes are usually steamed or boiled, though baking is also a possibility. Slip the washed and trimmed artichokes into the boiling salted water or arrange in a steamer. If cooking in the liquid, cover, bring the water to a boil and then turn down the heat. Simmer for forty minutes or until the outer leaves may be easily removed. If steaming, the artichokes will probably take from forty minutes to an hour to cook. Check periodically to make sure that there is still water in the lower part of the steamer. Or pressure-cook for 12 to 15 minutes.

Want to dress up the artichokes? One of the easiest things to do is to cut off the upper portion of the leaves so that the tops of the artichokes are basically level. Loosen and spread the leaves apart, then sprinkle herbs between the layers. Use sweet basil, tarragon, thyme, or possibly marjoram or oregano, along with a sprinkling of salt. The herb’s fragrance will penetrate quite well. Another alternative is to season the cooking liquid. For this add the juice of a lemon, some onion and/or garlic, some celery, bay leaves or any other seasoning that you’re fond of.

When eating artichokes hot, dip the petals in melted butter or perhaps a seasoned mayonnaise (see Lemon Mayonnaise and Mayonnaise with Soy Sauce and Balsamic Vinegar) on their way to your mouth, or take a look at the other suggestions in the Asparagus section.

Asparagus

Fresh asparagus is a wonderful treat, which used to be available for only a short time in the late spring, when the new shoots of the asparagus plant are harvested. The cut end of the shoots may be set in water to help maintain freshness. This stem end at its base is frequently white and tough to chew. The tough part of the stem can be removed by gripping it as close to the end as possible and snapping it off. The shoot will break right at the tender eating mark. The asparagus is now ready to be eaten raw or cooked whole, boiled or steamed, or to be cut up for sautéing. Cook asparagus only until tender. Anything short of this is tasty too, juicy with a slight crunch. Hot or cold, asparagus is often served with mayonnaise, but there are many other possibilities.

Basic Asparagus

These are some basic options for cooking asparagus with water. Other options for cooking would include grilling, roasting, and sautéing/steaming. Cooking with water will accentuate the invigorating green-leafy quality of the asparagus.

Asparagus

Water

Salt

Melted butter and lemon juice or seasoned mayonnaise

Prepare the asparagus by snapping off the tough ends. Place in salted boiling water and when the water returns to boiling, turn the heat down so that the asparagus simmers, or steam the asparagus on a metal rack over boiling water. Another method is to tie a bunch of asparagus together with string, and cook all of them together standing on their end in water. If the asparagus is to be served cold, some crispness is especially appetizing, so cook the asparagus anywhere from 2 to 8 minutes, depending on how much crispness you want. To cool, spread out the asparagus on a large dish towel. Boiled or steamed asparagus is good with melted butter, lemon juice, or a seasoned mayonnaise. One attractive serving arrangement is to put the mayonnaise at one end of a platter, then arrange the asparagus to be swimming toward it.

Lemon Mayonnaise

Taste buds will perk up when the asparagus, as well as the artichokes, are served with this seasoned mayonnaise.

Mayonnaise

Lemon or lime juice

Salt (optional)

Garlic (optional)

Season the mayonnaise to taste with lemon juice. Taste for salt. Add finely chopped or macerated garlic for a poor cook’s aioli. Lime juice is also fine.

Mayonnaise with Soy Sauce and Balsamic Vinegar

This mayonnaise recipe also goes well with artichokes.

Mayonnaise

Soy sauce

Balsamic vinegar

Season the mayonnaise to taste with soy sauce and balsamic vinegar.

Asparagus with Guacamole

Deep green and light green blending.

Asparagus

Guacamole

Cook the asparagus as in the basic recipe, and serve with a guacamole dip.

Basic Asparagus Over Easy

Asparagus can be cut on long diagonals or Chinese rolling cut for sautéing. After it’s cut, then it’s sautéed.

Asparagus

Yellow onion

Carrot

Oil

Salt

Nuts (optional)

Snap the tough ends off of the asparagus. Then cut in oval shaped pieces (diagonally) about ¼ inch wide, leaving the buds intact at the tender tip end. Slice or dice the onion and cut the carrot in ovals, rolling cut, half rounds, or what-have-you. Sauté the onion for about a minute. Add the carrot and fry this with the onion for a minute or two. Then add the asparagus and a little salt. Toss with the onion and carrot for a minute, then add a small amount of water (or white wine), put a lid on, turning the heat down to medium or medium low. Cook for 2 to 5 minutes until tender. (The smaller the pieces, the shorter the cooking time.) For variation, sprinkle with roasted, chopped nuts.

Broccoli

One of cabbage’s many cousins, broccoli makes green, succulent eating. The broccoli flowerets extend from a thick main stalk. Both the flowerets and the stalk are edible, but the outside of the main stalk is generally tough and stringy. To use the stalk, cut it loose from the broccoli and trim off the tougher outside layer. Cut as you wish—without the outside layer it’s a very tender delicacy.

Cut apart the flowerets into bigger or smaller pieces, as you prefer.

Broccoli will have a more subtle taste, a bright green color, and an especially pleasing texture if it’s not overcooked. It has a strong flavor of its own, so it can stand being well seasoned. If the broccoli flowerets have bloomed yellow, the broccoli is past its peak, and is best served with a hearty sauce or put into soup.

Blanched Broccoli

Many vegetables taste great with butter, lemon, salt, and pepper, and broccoli is certainly one of them. Again the key here is to err on the side of undercooking the broccoli rather that overcooking it. So get the broccoli out of the water while still firm, as it will continue to cook.

Broccoli

Water

Salt

Pepper

Butter (optional)

Cheese, grated (optional)

Lemon juice (optional)