Starting just after the day of the full moon in September and continuing through the next two weeks, my family liked to remember all our relatives who had died. On my grandfather’s Moon Day, year after year, we prayed, fed our priests and ate mightily well ourselves. We thought of our grandfather and hoped that he might be thinking of us. My grandfather was the first man – the first human being – that I had watched dying. I had not actually seen him die. I remember with great guilt now that when a cousin came running to inform me that my grandfather was actually dead, I felt cheated. Cheated because I had missed the moment. I had not seen human life stop. He had been dying for months, you see. I had watched his six-foot-tall frame shrink while the skin around his bones became almost translucent. His arrogance kept him going. His arrogance and his brilliance. He was just too powerful to be sucked away. So he went on living, much longer than he probably should have.

I remember one still May evening. It was too hot to sleep indoors so cots with crisp white sheets had been laid out on the lawn. There must have been at least forty cots. We were a large family, what with cousins, aunts and uncles. All of us were uneasy because of Grandfather’s condition. An oxygen tent had been placed near his cot and all the elders were taking turns holding the oxygen mask to his face. Once, when it was my mother’s turn, she turned to me and said in a whisper, ‘Hold the mask. I have to go inside for a minute.’

I felt like a soldier that had been called to duty. I held the mask up to my grandfather’s mouth and nose without blinking or moving a muscle.

There must have been something about the position of my rigid hand that my grandfather did not care for. He lifted his very frail arm with great effort and gave my hand a gentle push.

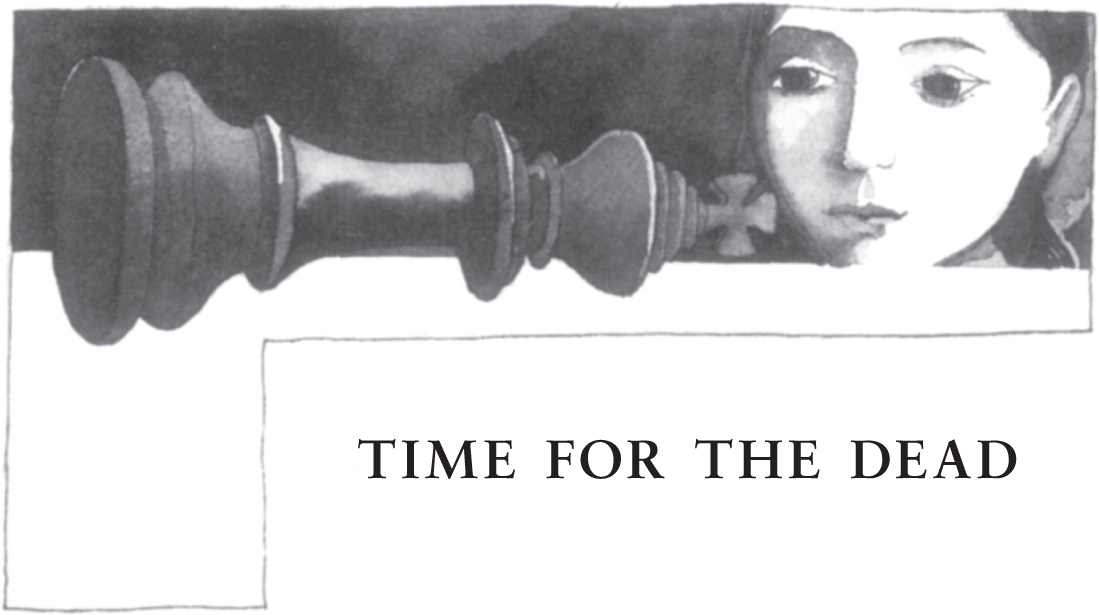

In that one touch – that last touch – were all the moments I had shared with my grandfather. There was a time when I was five and he had dipped his finger into his glass of whisky-soda to give me my first lick of alcohol. There was the time when he had lifted me up to ride with him in his phaeton carriage. And there was the time when he was teaching me chess. He had put his hand on mine and helped me lift my Queen into the air. ‘Now knock the King down and say “checkmate”. You have won. Don’t you see, you have won.’