3

3

3

3

THE JADE EMPEROR’S MIND SEAL CLASSIC

Refining the Three Treasures

After first reading through the Chinese text of The Jade Emperor’s Mind Seal Classic, I admit I wasn’t all that enthusiastic about translating it, as it appeared to be nothing more than a collection of Taoist aphorisms, disjointed and unclear in purpose. But I kept returning to it as a reference while translating and studying other Taoist materials. Eventually, I realized why Taoist monks, especially of the Chuan Chen (Complete Reality) and Lung Men (Dragon Gate) sects, found it so valuable in their daily rituals and festival ceremonies. The Jade Emperor’s Mind Seal Classic is, without question, a concise overview of what a Taoist aspires to spiritually.

Those unfamiliar with Taoist terminology might view this text as mere mystical gibberish, but for the Taoist monk it is a tool for mindfulness. Indeed, all Taoist practices—whether meditation, yogic inner alchemy exercises, visualizations, recitation of mantras or sacred texts, or ceremonial rites—are ultimately exercises in mindfulness, a self-hypnosis or autosuggestion of sorts.

The Jade Emperor’s Mind Seal Classic was used daily by Taoist monks of the Complete Reality and Dragon Gate sects. It was also recited on auspicious days by other sects. At Po Yun Miao (White Cloud Monastery) in Beijing, records show that this text was held in high esteem and that the novice Tao Shih (Taoist monk) had to memorize it during his one-hundred-day training period before ordination.1

Hopefully, you will come to share my belief in the importance of this text.

The underlying message of this classic is that within each of us dwells the “medicine” to cure the affliction of mortality. We possess the seeds of primal forces, which when cultivated properly will confer great spiritual benefits. The “open secret” of nourishing these seeds is none other than our own tranquillity—to let the dust settle so that we may see with utmost clarity the seeds of immortality.

The Jade Emperor’s Mind Seal Classic is extremely important to our modern-day society, not only for the achievement of immortality (a difficult concept for many Westerners to grasp), but also for the achievement of health, longevity, and spiritual insight. With all the stresses and illnesses afflicting our society, the experience of tranquillity could be the greatest medicine of all. We need not accept the lofty Taoist goal of immortality to understand and seek out these other jewels along the Way.

Historical Background

This brief text was probably composed sometime during the Sung dynasty, under the reign of Emperor Hui Tsung, who had originally deified the Jade Emperor as Lord on High and erected temples in his honor. Although various other texts use the term Mind Seal (as used here, a synonym for immortality) in their titles, there are two extant texts of this classic, one arranged by Lu Szu-hsing and a later version by Chio Chen-tzu. The earlier of the two was written during the Ming dynasty and is titled Yu Huang Hsin Yin Miao Ching (The Jade Emperor’s Profound Mind Seal Classic), and has an attached commentary by Lu Szu-hsing.

Lu states in his commentary that the most important verse of the entire text, which is taken directly from the Tao Te Ching (Classic on the Way and Virtue), tells us to “keep to nonbeing yet hold on to being.” An adept’s empirical understanding of the meaning of this verse will help him reverse the light of the yuan shen (primal spirit). This in turn will create a “quickening of the qi” and enable self-illumination. The verse points directly to the experience of creating a Spiritual Fetus—a being, yet a nonbeing. Within Lu Szu-hsing’s version of this classic are appended verses that do not appear in other compilations, suggesting that they are most likely his own inventions. Chio Chen-tzu of the Ching dynasty omitted these verses in his reformation of the text, which is presently the accepted version of the classic. For the sake of clarity I have placed Lu’s appended verses at the end of the English translation.

Lu Szu-hsing divided the text into twenty-four separate verses (Chio Chen-tzu discarded this arrangement) and provided select discourses on nourishing the ching and qi, inner alchemy, congealing the Elixir, and releasing the Spiritual Child. In his introduction to the text he provides many related quotations not only from Taoist sources, but from Buddhist and Confucianist ones as well. The entire work is presented in much the same manner as The Secret of the Golden Flower (T’ai I Chin Hua Tsung Chih), although retaining a greater sense of Taoism and being much less eclectic. Unfortunately, it can also be a bit confusing to the noninitiate. Chio Chen-tzu did well to simplify the text and commentary. The work presented here lies somewhere in the middle of their two texts, although it leans toward Chio Chen-tzu’s version.

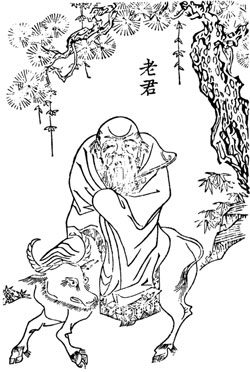

Lao-tzu

No clear evidence suggests who the original author of the classic truly was, but this is not important. What is important, however, is the terminology used throughout the text, as many of the ideas are derived directly from the Tao Te Ching, from the Chuang Tzu, and from the Pao P’o Tzu.

To determine the period of original authorship would help clarify whether the cult of the Jade Emperor was an integral part of early folk religion (Taoism adapted portions of this cult into its beliefs) or whether it was an invention of the first organizer of popular Taoist religion, Chang Tao-ling (born A.D. 34, later Han dynasty). Chang is believed to have lived 123 years and was the founder of the Heavenly Masters sect.

Chang Tao-ling

Origins of the Jade Emperor

The Jade Emperor is part of the Taoist trinity, of which he is the head. On his right side stands Tao Chun and on his left, Lao-tzu. They are commonly known as the Three Pure Ones (San Ching). In more practical Taoist terms they are but symbols of the true trinity: primal (yuan) ching, qi, and shen.

Yu Huang (Jade Emperor), sometimes called Jade Ruler or Pearly Sovereign, is, for the most part, identified with Brahma of Hinduism, Indra of Buddhism, and, to a lesser degree, the notion of God Almighty in Judeo-Christian and Islamic traditions. He represents shen (spirit), t’ien (heaven), Primal Cause, and present time.

Tao Chun (Sovereign of the Way) represents ching (regenerative force) and is identified with the Pole Star God. He represents jen (humanity), the interaction of yin and yang, and time past.

Lao-tzu (Old Philosopher) represents qi (vital life force energy) and is identified by the Taoist doctrine. He represents ti (Earth) and future time.

The Jade Emperor’s Mind Seal Classic refers to these three forces as the “supreme medicines,” the curative and preventive prescriptions for both physical and spiritual ills, as well as the compound for the true Elixir of Immortality. The text is very brief, consisting of only two hundred characters arranged in four character couplets, which allowed the Taoist monk to easily memorize them and recitate them rhythmically. The contents of the text covers a wide range of ideas crucial to the Taoist cultivator, reading more like a crib sheet to keep the mind on the essentials for attaining immortality—of which ching, qi, and shen are the foundation.

The Jade Emperor, along with the Eight Immortals (Pa Hsien), stands as one of the most popular of Taoist celestial beings. A host of other spiritual beings and immortals are part of his court. In popular tales, however, he is not always revered. He rarely intimidates the immortals of lesser rank and is often tricked by them into granting favors and promotions, not unlike earthly leaders. It is not a job to which most immortals aspire, as the powers of that position do have their limitations.

There are various interesting accounts as to how he became the Jade Emperor, as well as three versions of his ascension. It is purely a matter of personal belief as to whether any of them is truthful. Mythic history, however, more often than not has its base in factual and documented history. Some truth is always embedded within the myth. Myth is valuable for its unique ability to open up and expand the mind, an exercise in imaginative powers that is important to any spiritual endeavor, Taoist or otherwise. Dealing with just raw facts tends to block the mind from its creative instincts. Inner illumination is far more important to the Taoist than any worldly exercise of fact finding.

Any of the following three accounts would serve well to explain the Jade Emperor’s origin, since this august figure is more symbolic than personal. The first account is probably more fact than fiction, whereas the last two accounts are most likely just “wild history.” But to the Taoist the last two accounts might be more acceptable in that they have a higher inspirational value than the redundant first account—an attempt simply to compile raw data.

First Account:

The Immortal Chang Deified as the Jade Emperor Sung Dynasty (A.D. 1116)

As Buddhism took hold in China during the Tang dynasty, the various Taoist orders grew envious of the well-organized Buddhist communities, which erected beautiful temples for their patrons. They became envious also of the Buddhist paraphernalia: its spiritual images, disciplines, rituals, and volumes of literature. When Buddhism gained imperial patronage, great pressure was applied to the Taoist representatives to get back into the court’s grace and to regain the attention of the public at large.

The Taoists raised funds to build temples and monasteries, established the Taoist Canon, formulated rituals, and began arranging their own hierarchy of spiritual beings. The beings were not necessarily new to Taoism, but this was the first sincere attempt to present them in an orderly fashion to the outside world. During this period the topknot was fashioned for all Taoist monks and priests. The Buddhists considered this just a ploy to differentiate the Taoists from the bald-headed Buddhist monks.

The Jade Emperor was created mostly as a counterpoint to the ever growing popularity of the Buddhist trilogies: Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha; Amitabha (past Buddha), Shakyamuni (present Buddha), and Maitreya (future Buddha); and the Pure Land sect’s trilogy of E Mi To Fo (Amitabha Buddha), Kuan Shih Yin (Avalokitesvara) Bodhisattva, and Ta Shih Chih (Mahasthamaprapta) Bodhisattva, which gained great popularity throughout China. In response, the Taoists formulated their own triad, called the Three Pure Ones, which consisted of the Jade Emperor, Tao Chun, and Lao-tzu. Other triads were created but did not gain the broad acceptance that the Three Pure Ones have today.

It is thought that the Jade Emperor, in his early life, was a member of the Chang clan. Almost all Taoists take Chang as their surname in order to connect themselves with the famous lineage of Chang Tao-ling of the later Han dynasty, the founder of what is called religious Taoism. Some propose, however, that he was a well-respected magician and alchemist who lived sometime during the early Tang dynasty.

Chang’s deification as Jade Emperor, the Supreme Ruler, did not occur until A.D. 1116, in the Sung dynasty. He was deified, under some suspect conditions, by the Sung dynasty emperor Hui Tsung. It seems that an outcast Buddhist monk, Lin Ling-su, managed to convince the emperor to deify this Tang dynasty magician as Supreme Ruler, claiming that the Buddhists were not indigenous to China and that it was not in the empire’s best interest to allow Buddhism to gain such popularity with the masses. Ling made the argument that if the people of China adopted the foreign export of Buddhism, they might very well impeach the emperor in favor of a foreign one. But this was not Lin’s true motive. As soon as the deification took place, Lin attempted to place himself at the head of this new Jade Emperor cult. He hoped thereby to crush the Buddhist influences prevalent in society and take revenge against the Buddhist clergy responsible for ousting him. The Jade Emperor was deified and gained broad popularity, but Lin Ling-su never achieved the role of patriarch of the cult.

Second Account:

Emperor Chen Tsung’s Edict from the Jade Emperor Sung Dynasty (A.D. 912)

Long before the creation of the Jade Emperor triad of the Three Pure Ones, there were other, similar triads in certain Taoist circles. The Jade Emperor, it appears, is just one in a succession of Supreme Rulers. The first on record is T’ai Yi, who abdicated in favor of Huang Lao-chun, who in turn abdicated to Yuan Shih T’ien-tsun, who finally abdicated his throne to the Jade Emperor. However, it is said that when Maitreya Buddha2 enters our world, the Jade Emperor will abdicate his throne to yet another accomplished immortal, and he will descend in order to serve the next Buddha. Here is yet another interesting aspect of Taoism, at least in its religious context. Chosen immortals, Gods on High, serve only for a limited time (vast by human standards, as each day and night of the Jade Emperor’s existence equals about five hundred years of the mortal concept of time).

The popular belief of why the Jade Emperor was introduced as a Supreme Being is that Taoists needed both public and imperial patronage. Taoists used the Jade Emperor as an object of veneration and meditation, not unlike the Buddhist Pure Land practices surrounding Amitabha Buddha (Buddha of Infinite Light) and Kuan Shih Yin Bodhisattva (Contemplator of the World’s Cries). To a lesser degree, it gave them something that would compete against all the popular Confucian rites and ceremonies.

Buddhists claim that the Jade Emperor is now waiting in the Tushita Heaven with Maitreya Bodhisattva studying the Buddhadharma. Because of his inconceivable and limitless past merits, the Jade Emperor is now serving as Supreme God until his introduction as a bodhisattva into this realm, where he desires to teach joy, the dharma of Maitreya. This claim comes as no surprise because Buddhists usually take the stance that all accomplished Taoist immortals, sages, and divine beings are actually transformation bodies of Buddha’s disciples and/or a particular transformation of a bodhisattva. The best example is Lao-tzu, who is thought to be none other than Mahakasyapa, the First Patriarch of Ch’an Buddhism (Zen). It was Mahakasyapa who first became enlightened by the wordless teaching after seeing the Buddha twirl a flower in his hand, and he is now deep in samadhi within the Chi Chio Shan (Chicken Foot Mountains) awaiting Maitreya’s entrance into this realm.

Furthermore, there was this tendency, especially in the Sung dynasty, to intermix Taoist figures with those of Buddhist teachings. Reasons for this varied, as in some cases it was a Buddhist effort to keep Taoism under its thumb, so to speak, and in other cases it was the organized religious Taoists themselves attempting to incorporate themselves into the popular following of Buddhism. But more often than not, it was the emperors themselves, as they had to play both ends against the middle so, keeping the masses happy by melding the two. Yet despite all the political maneuvering and arguments, many Taoists and Buddhists believed that spiritual beings, be they Buddhist bodhisattvas or Taoist immortals, were part of a vast pantheon of spiritual beings and that it was only human semantics creating their separation. We see all this really coming into popular belief in China during the Ming dynasty in the folk story the Journey to the West, by Wu Cheng’en.

In this epic myth there are numerous references to the Jade Emperor and his Palace of Miraculous Mists. This novel of Chinese folklore, probably more than any other work in Chinese literature, popularized the belief in the Jade Emperor, who with his retinue—a vast array of gods, immortals, and spiritual beings—fights the evil spirits and forces within the heavenly and earthly realms. The references made to the Jade Emperor are too numerous to list here, as are the descriptions of his heavenly abode. Even though the celestial prime minister is not always regarded kindly by this primarily Buddhist novel, Journey to the West is well worth reading for anyone interested in Buddhism, Taoism, or Chinese mythic culture in general.

The novel, which was written during the Ming dynasty, is in one sense an anthology of Chinese folklore and a catalog of the numerous spiritual beings. From another perspective, it is a metaphor on the progression of spiritual cultivation (integrating Buddhist, Taoist, and Confucian methods). We all carry within us aspects of its main characters: the Monkey King, Friar Sand, Pig, Horse, and Hsuan Tsang the monk. Indeed, it would be hard to imagine that anyone could understand Chinese spiritual concepts without having read this work. Beyond this amusing tale lies a very profound and mystical message for those engaged in spiritual cultivation.

The above account of the Jade Emperor coming into power and his predicted abdication was supposedly reported by the emperor Chen Tsung of the Sung dynasty (A.D. 912), who received in a dream an edict from the Jade Emperor himself, informing him that he was about to take charge of heaven and reside in the Palace of Miraculous Mists and that the next earthly emperor was to deify him as Yu Huang Shang Ti (Jade Emperor Supreme Ruler). Consequently, Emperor Hui Tsung did deify the Jade Emperor in A.D. 1116 and began erecting temples and images in his honor under the influences of Lin Ling-su.

Third Account:

The Mythical Version of the Jade Emperor Sung Dynasty

The Jade Emperor is thought to be the son of an emperor named Ch’ing Ti, who had a consort called Pao Yueh-kuang, who interestingly enough is thought to have become a spiritual attendant of the Taoist matriarch Hsi Wang Mu (Western Royal Mother), called Hsuan Nu (Mysterious Girl), who promulgated sexual teachings that led to immortality and as well dispensed Peaches of Immortality to deserving mortals when so directed by the Western Royal Mother.

Pao had reverently prayed to the gods for a son, as the emperor still had no sons to inherit his throne. She became pregnant, much to the happiness of the emperor. The astrologers predicted a son would rule all of heaven and earth, and this child was most certainly a male.

As foretold, brilliant light shot forth from his body and all his physical features were perfect. The story goes on to claim that the young boy had great and far-reaching intelligence and very deep compassion for all living things. When he finally came of age and inherited his father’s throne, his acts of charity to the homeless, sick, impaired, orphaned, and unjustly treated were very generous and kind. After his father’s death, he left the empire, resigning his throne, and traveled to the Pu Ming Mountains to meditate, whereupon he achieved immortality.

After his departure from this world he was reborn, and for eight hundred successive lifetimes taught the common people about spiritual matters and doctrines. For another eight hundred lifetimes he returned to this world to cure the sick and instruct the common people on medical matters. Then for another eight hundred lifetimes he practiced unconditional compassion in both the hells3 and on Earth. He descended to this world for yet another eight hundred lifetimes to patiently endure suffering. It was upon the completion of these thirty-two hundred lifetimes of spiritual practices that he finally became the first of the verified order of Golden Immortals. He was deified and ascended to the position of Supreme Ruler, called Yu Huang Shang Ti.

From this account the Jade Emperor supposedly received his name, Yu (Jade). Since his father’s name was Ch’ing (Pure and Bright) and his mother’s was Pao Yueh-kuang (Moon Light Gem), the two names in combination symbolized white jade (yu).

Explanation of Terms

Yu Huang (Jade Emperor)

The most important question concerning the origin of this text is whether or not it existed before the popularization and deification of the Jade Emperor himself. His name is mentioned only in the title and not in the text itself. Therefore, it is quite possible that the text did exist before the Sung dynasty and that sometime during or after the Jade Emperor’s deification under the emperor Hui Tsung his name was attached to the title.

The sixth line of the text refers to the Shang Ti, thought to be the Jade Emperor. But it must be remembered that the term Shang Ti existed long before the introduction of the name Jade Emperor. Lao-tzu was also given the honorific title of Shang Ti, as were others in the Taoist mystical pantheon. Also, if taken in the plural sense, the term might mean the Three Pure Ones (San Ching, the Taoist trinity).

The term Shang Ti was first used in ancient China as a title for the head of a clan. Only later was it applied to supreme beings. In connection with the Jade Emperor, Shang Ti means the “Lord on High” or “Sovereign of Heaven.” He is the supreme authority of all other gods and deities. Earthly emperors were considered his “Sons of Heaven.” The Shang Ti is a summation of all the various Taoist hierarchies of gods. When one of them reaches a certain level of spiritual perfection and merit and the Jade Emperor decides to abdicate, then this god will replace him. There is another group of mythic supreme beings called the Jade Rulers, and this consists of Fu Hsi, Shen Nung, and Huang Ti. They, however, have no relation to the Jade Emperor in either lineage or the history of his creation.

Interestingly enough, the main controversy overshadowing the cult of the Jade Emperor has nothing to do with the legitimacy of his title Lord on High or Sovereign of Heaven. Even Buddhists and Confucians recognize his lofty position. The real controversy lies in the question of why he was originally introduced into the Taoist pantheon.

Taoism is not a teaching about mysticism; it is mysticism. Taoism, as one learns through study and practice, is paradoxical, at least to the Western way of thinking. No paradox exists, however, in the Chinese mind. For the typical Western mind contemplating Taoism, the Supreme Being does not really seem to exist. A Westerner could conceive of Tao, the primal spirit (yuan shen) in each of us, as the source of all things—an impersonal, creative force—but then have trouble viewing the mysticism, the Jade Emperor, and all the various spiritual beings as anything other than symbols. A true Taoist, however, would have no difficulty in seeing the Jade Emperor as the Supreme Lord of Heaven, but in the same breath consider this august figure just a symbol of yuan shen. To the Taoist there is no contradiction in these seemingly opposing views—one being an outer expression of religious practice and the other a self-empowered, internal expression of spirituality devoid of religious tenets.

The underlying doctrine of Taoism is that humans and heaven are but reflections of each other and are one, for in each human lies both a Heavenly Spirit (Hun) and an Earthly Spirit (P’o).4 Therefore, to the Taoist there is no real contradiction in the religious practice of worshipping a God, yet to the Taoist this would be better termed as “paying reverence to” because it tends more toward the idea and practice of paying reverence than to actual worship. There is a problem when one thinks that religious practice is the only means of spiritual enlightenment. Using a personal god has never been a foreign practice to Taoism, but it was also never taken as a final answer or as the true reality. Like Buddhists, Taoists view gods and spiritual beings as still engaging in the process of cultivating their spiritual growth and being subject to retribution for their actions, just as human beings are—whereas Western religions tend to perceive God as a manifestation of fixed perfection. This perception is one of the great divisions between Eastern and Western thought.

It is now easy to see why Lu Szu-hsing considers the verse in the Tao Te Ching “Keep to nonbeing, yet hold on to being” as extremely important and why it has been the main paradox of Lao-tzu’s philosophy. This verse can be interpreted in many ways, but for the purpose of understanding the perspective of the Jade Emperor it might be interpreted as “Keep to the idea of no supreme being, yet hold on to the idea of a supreme being.” It is not in keeping with Taoism to view anything as absolute, supreme being or not. There is obviously an enormous difference between attaching to such things in a one-sided manner and the acceptance of both sides of an issue. Extremist views tend to destroy themselves and converge into their opposites.

Again, in the Huang Ting Ching (The Yellow Court Classic) hundreds of spirit-gods are named and assigned to specific parts of the body, both internally and externally. The Jade Emperor’s Court is, in essence, the “court of inner man.” Taoism, seen in this light, is not dogmatic or even religious (at least in the Western meaning of the term). Indeed, in the Chinese language the word religion is only a century old, having been introduced by Christian missionaries.

Originally, Buddhist, Taoist, and Confucian ideas were simply referred to as teachings. The notion of a dogmatic religion was entirely foreign to the Chinese until the intervention of Western beliefs. So when the Taoist speaks of a Supreme God, the language is not the same as when a Western Christian speaks of God. Whereas the Christian speaks of something external and distinct from himself, the Taoist is speaking of something external but simultaneously connected to his own inner being. Heaven and the Jade Emperor are seen not only as truly existing, but also as symbols. Externally, they reflect what is going on here, but aren’t involved or necessarily concerned with our affairs.

Hsin Yin (Mind Seal)

Hsin Yin is a most difficult term to translate into English, which also makes it difficult to explain. Frequently, the term Mind Seal is used interchangeably with the word immortality. The Mind Seal is not a matter of ritual or some ceremony wherein a student can just hear some words and become an immortal. The Mind Seal is an instant awakening to the truth of how to become an immortal, an event beyond all words and rationalization that instantly seals the spirit. The Mind Seal may be experienced through a metallurgical process (the Eight Minerals formula) and herbal intake (several remedies were supposedly created, all called the Pill of Immortality); through spiritual alchemy (by means of attaining tranquillity), which results in the Elixir of Immortality; or through spiritual psychic experiences (like receiving the Peach of Immortality from the Western Royal Mother of one of her female attendants in a dream or state of tranquillity). All of these cause what the Taoists call Mind Seal.

The term has three very profound and subtle, interconnected definitions. The first is a deep and abstract experience of truth gained from the successful practice of meditation, which seals the mind forever from reentering a state of illusion and physical bonds. The realization is wordless, and therefore cannot be communicated through language.

A Taoist seeker was wandering about a mountain range in search of a true teacher. He had wandered many such mountainous areas, yet never found anyone who he thought really had achieved immortality. On one occasion he happened upon a small Taoist hermitage high atop a peak on Wu-T’ang Mountain, where a small number of venerable old immortals (priests) were living. They invited him to stay for rest and food as long as he liked. Though he found these men extremely wise and charming, he did not think they were true immortals. But he did find the place comforting and he decided to stay on with them to learn and rest. One evening, while talking with one of the priests, he asked who the man’s teacher was and how he came to be living in this remote place. The old Taoist laughed and told him he was a disciple of a high immortal who mounted the back of dragon many years ago and ascended to an Immortal Paradise. In regard to how he got to his present abode, he simple answered, “Does a lone leaf really care or know where it goes under the gentle guidance of the wind? Does it seek to understand such things? The Tao of the leaf is no different from mine. We are where we are supposed to be.” The seeker then said, “Since your teacher is gone I have missed a great opportunity to meet and possibly study with him. This is so regrettable.” The old Taoist retorted, “I didn’t say he was gone. I said he mounted a dragon and went to an immortal paradise. You mortals always have to define things as absolute: life and death, black and white, here and there.” At this point the old Taoist politely excused himself, wishing to go cross his legs in his chamber for the remainder of the night. The statements made by the old Taoist seemed to cut very deep into the mind of the seeker, bringing him to almost a tearful state and causing him to reflect throughout the night.

A few days later the seeker decided to take a stroll. The entire area of the hermitage was very serene and one couldn’t help but get immersed in its ambience of tranquillity. As he walked about he came upon a cave opening and thought he might explore it. He entered and soon saw light coming from the end of one of the corridors. As he drew near, he saw a very surprising sight: A man with very long gray hair and a dark blue robe was sitting cross-legged, facing out over a vista of seemingly endless valleys below. The robed man sat so still that the seeker was unsure whether he was dead or alive, a being or a statue. As he drew within ten feet of the figure, he heard the soft words, “What are you searching for, Sung-wei?” Sung-wei was the man’s birth name, which he used as a child, and which had been known by only a few people fifty years ago. The seeker was scared, dumbfounded, and unsure of what he had heard. He responded nervously, “For immortality, venerable sir. Are you talking to me?”

“I see no other mortal demons here, so yes, I must be talking to you,” the strange man said as he effortlessly turned his entire body around without uncrossing his legs. “And how may I be of service to a such a wretch as yourself?”

Taken aback by such harsh language, the seeker thought he should just leave and not engage in conversation with this man. But the appearance of the man struck him as peculiar—he had never before seen anyone who looked so old and young simultaneously, so vibrant and yet still, and seemingly there but not there. As he was observing the man and contemplating how to bow and apologize for his intrusion before departing, the man invited him to sit. The seeker did so, and after a long silence the man spoke to him.

“You seek immortality because you fear what death has to offer. The pleasures of life have entrapped you like a koi swimming about aimlessly in its pond, constantly searching for bits of food to sustain its life. In its search for food it soon grows old and weak. It wishes to be young again, to regain its vitality and strength. People are like this too. It is a mortal condition to struggle with the realization of the quick pace of aging, so people constantly search to regain bits of their youthfulness, or to become an immortal so they can forever be what they are because they dread their present condition. This is what you are searching for.

“But you must ask yourself, if what you are is so undesirable, why would you seek to immortalize it? Actually, I ask this knowing full well you do not have the answer. It is not your body you wish to immortalize; it is your mind you wish to keep forever. The body is just an illusion and is what keeps you from being immortal. What you see before you now is only what I want you to see. What I see before me now is only a reflection of everything you have thought and done. In your ignorance you want to immortalize your body because you think that is you. Seek to immortalize your mind. Then you may have whatever body you wish, when you wish. It is the mind that creates everything, but the bond to your body limits the illimitable workings of the mind.

“In your ignorance you want to immortalize your body because you think that is you. Seek to immortalize your mind. Then you may have whatever body you wish, when you wish.”

“Immortals are no more than mortals like you who discovered how to seal their spirits [consciousnesses] so that no trace of the illusion and attachment they previously carried concerning their bodies exists. When reaching the highest states of tranquillity, only the mind exists and it can then function purely of itself. This sealing of the spirit [mind] is what you are searching for. So cease all your wandering, cease all your false thinking, and cease all your physical attachments.

“When I was a mortal I missed thousands of opportunities to become immortal. All mortals are constantly provided with the means to immortality. It is purely a law of nature for things to become immortal. There is no one path of life, birth and death. There are two paths: mortal and immortal. The former is the physical [p’o, animal] path, the later is the mental [hun, spiritual] path. Because mortals bond so completely with the p’o, the hun is completely neglected.

“In your life you have had possibly thousands of sexual orgasms. Each of these was an opportunity to achieve immortality. But since all your attention was on just the physical sensations, you missed the spiritual possibilities. When you learn to reverse this process and use that blissful moment of pure tranquillity, immortality can be achieved.

“Nature [Tao] provides endless means for immortality, just as it provides endless means for physical sustenance. It is the mortal’s choice as to which to seek. Our great ancestor Lao-tzu rightly said, ‘Heaven [Tao] treats all men as straw dogs.’ Tao provides all things but compels no one to draw from them. All you need do is seal your spirit, then all is done, immortality is yours.”

With this said the seeker returned to the hermitage. When he told the old Taoist of whom he met and spoke with, the old Taoist responded sharply, “No, I told you he mounted a dragon and went to an immortal paradise. Don’t speak of this again.” Just as he finished saying this, the old Taoist flung out a fly whisk from the sleeve of his robe and hit the seeker hard across the face with it. Immediately the seeker saw that the old Taoist had completely changed appearance and was now the old man in the cave. Both grinned broadly at each other and the old man spoke, “Try your best!” as he turned and walked away singing. The seeker made his residence at the hermitage and never left. To this day visitors to the mountain sometimes hear men far off in the distance singing and laughing.

The second meaning relates to the procedure and experience of wordless, mind-to-mind transmission from teacher to disciple. In this sense of the term it is the teacher who seals the mind of the disciple on a particular doctrine or realization. Though words might be used between the teacher and the student, it would prove quite impossible to translate those words into something comprehensible to anyone else. The disciple would be on the brink of a final realization and the teacher need only introduce the proper catalyst for the disciple’s transformation.

There once was an old monk who taught each of his disciples according to their own character. This meant that his teachings appeared to be different for each individual. The old monk was unorthodox, yet was considered a high immortal. He rarely spoke and more often than not communicated through peculiar gestures that were meant to seal the mind of a disciple when he felt the conditions were ripe for transmission. In the case of one student, the teacher would simple extend his thumb and point it aggressively at the disciple no matter what the youth asked. Years passed and the disciple was eventually put in charge of training novices on scriptural matters. He imitated his teacher, so that every time a novice would ask a question of him he would raise his thumb and point it at him. One day, while the young monk was standing by the well to collect water, his teacher happened along. The teacher walked to the edge of the well and looked down into the depths. Smiling, he looked directly at the student and asked, “When I look down in the well the water is dark and mysterious, but when you draw it up it appears clear and pure. Is this the nature of the water or the nature of you?” The disciple extended his thumb boldly at the teacher. Immediately the teacher drew a sharp knife from his robe and swiftly cut off his disciple’s thumb. The disciple looked in horror at his thumbless hand and then at his teacher, who was now extending the severed thumb toward him. Both broke out into loud laughter. The disciple broke out in verse and said, “The Tao is deeper and more mysterious than the greatest of wells, and from it I have now drawn the precious elixir. The thumb may be gone, but my spirit is now everlasting.” Other disciples who witnessed this event claim both men leaped into the air and chased each other like children atop the tall pine trees.

The third meaning is very ancient in both China and India. It was seen as a symbol, wan tzu,  , a swastika. While the swastika invokes the image of Nazi Germany to the Western mind, it was not intended for this end. Hitler took the symbol and reversed the image for his purposes. But in ancient China the swastika, in its original form, was a spiritual symbol of auspiciousness and eternal life (immortality).

, a swastika. While the swastika invokes the image of Nazi Germany to the Western mind, it was not intended for this end. Hitler took the symbol and reversed the image for his purposes. But in ancient China the swastika, in its original form, was a spiritual symbol of auspiciousness and eternal life (immortality).

It is said in Taoism that the correct swastika appears on the bottoms of the feet, on the forehead, or on the chest of immortals, thus showing their spirit has been immortalized and sealed. In this sense, this third use of the term Mind Seal—used in conjunction with the symbol of the swastika—is not a method of sealing the mind, but rather the indication of a mind that has been sealed.

In Buddhism this swastika is used as a symbol of Buddha’s heart. Taoism incorporated it into a symbol of immortality. In China this symbol was a very old form of the character fang, which meant the four directions. Later fang became associated with wan, the ten thousand things (all phenomena). Hsin Yin is a term interchangeable with wan tzu; hence, various translations could apply to these terms, such as “enlightened to all things” and “sealing the heart/mind within all phenomena.”

Wan tzu, fang, and wan

Yin also carries the variant meaning of “mudra,” a Sanskrit term for a sacred hand position used during meditation, during recitation of a mantra or scripture, and for warding off evil influences. Thus, Hsin Yin here could likewise translate as “mind mudra,” a sacred positioning of the mind.

Since Taoists used wan tzu as a symbol for immortality, the title of the work we are examining could easily be translated as The Jade Emperor’s Immortality Classic. However, the meanings implied by Mind Seal are more appropriate, as the purpose of the text was to transmit wisdom that could lead to spiritual transformation.

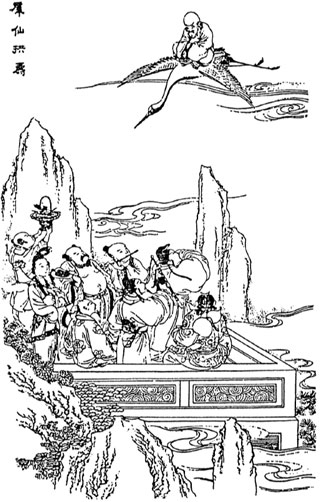

Lao-tzu riding a crane to visit the Eight Immortals

Ching means “to thread together,” as strands of silk are woven together to make fabric. The lines of the text, indeed the characters themselves, are thought to be woven together like strands of silk. There has never been a standard in English for the translation of this word, as it sometimes appears as canon, scripture, treatise, tractate, or discourse.

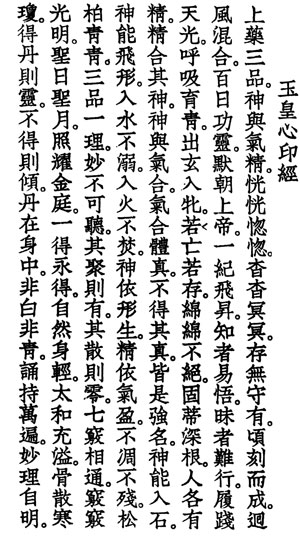

A Translation of

The Jade Emperor’s Mind Seal Classic

1. The Supreme Medicine has three distinctions:

Ching [essence], Qi [vitality], and Shen [spirit],

Which are elusive and obscure.

2. Keep to nonbeing, yet hold on to being

And perfection is yours in an instant.

3. When distant winds blend together,

In one hundred days of spiritual work

And morning recitation to the Shang Ti,

Then in one year you will soar as an immortal.

4. The sages awaken through self-cultivation;

Deep, profound, their practices require great effort.

5. Fulfilling vows illumines the Heavens.

6. Breathing nourishes youthfulness.

7. Departing from the Mysterious, entering the female.

It appears to have perished, yet appears to exist.

Unmovable, its origin is mysterious.

8. Each person has Ching.

The Shen unites with the Ching,

The Shen unites with the Qi,

The breath then unites with the true nature.

Before you have attained this true nature,

These terms appear to be fanciful exaggerations.

9. The Shen is capable of entering stone;

The Shen is capable of physical flight.

Entering water it is not drowned;

Entering fire it is not burned.

10. The Shen depends on life form;

The Ching depends on sufficient Qi.

If these are neither depleted nor injured

The result will be youthfulness and longevity.

11. These three distinctions have one principle,

Yet so subtle it cannot be heard.

12. Their meeting results in existence,

Their parting results in nonexistence.

13. The seven apertures interpenetrate

And each emits wisdom light.

14. The sacred sun and sacred moon

Illuminate the Golden Court.

One attainment is eternal attainment.

15. The body will naturally become weightless.

When the supreme harmony is replete,

The bone fragments become like winter jade.

16. Acquiring the Elixir results in immortality,

Not acquiring it results in extinction.

17. The Elixir is within yourself,

It is not white and not green.

18. Recite and hold ten thousand times.

These are the subtle principles of self-illumination.

Lu Szu-hsing’s Appended Verses

19. The two images of the dragon and tiger are unified through Qi; Chaos blending as One.

20. It is not possible to attain the eternal just through invocation.

21. The Elixir is called Green Dragon and White Tiger;

The Elixir is the nature of no-nature,

Emptiness of nonemptiness.

22. Even if you are unable to make use of the substance, You can certainly make use of the function.

23. Frequently both the substance and conditions

for the substance appear together, although

these are not always perceived as identical.

24. The ancients said, “The term emptiness embraces the entire teaching.”

1. The Supreme Medicine has three distinctions: Ching [essence], Qi [vitality], and Shen [spirit] . . .

The Supreme Medicine, or shang yao, literally translates as “the foremost healing herbs.” This includes not only the idea of a preventive or curative prescription for physical illnesses, but also a “wonder drug” for all mental and spiritual illnesses. These supreme medicines are not something external to the self, but are rather the very forces that constitute your existence. Taoists consider these forces to be the three primary energies within each human being: our physical and sexual essence (ching), our vital energy and breath (qi), and our mental energy and state of consciousness (shen).

Taoists believe that the essences of the material physical body, the breath that animates it, and the mind that makes us conscious of life not only confer good health, but, if developed to their highest potential, will likewise confer immortality. Conversely, dissipating sexual energy and abusing the physical body, disregarding the regulation of the breath, and never concentrating the mental energy will result in an unhealthy life and an early death.

The three forces are normally referred to in Taoist works as the Three Treasures (San Pao). It is the preservation and cultivation of these three treasures that promotes health, longevity, and immortality. Without these forces there can be no life, as it is the integration of them that constitutes existence. Their abundance determines the level and quality of your health and the length of your life. Their transformation into the Elixir brings about immortality.

Taoist philosophy contends that there is no reason for a person ever to suffer physical illness, and that death itself, whether from old age or sickness, is also unnecessary. Illness and death occur because of the dissipation and destruction of the Three Treasures.

At birth everyone acquires a varying degree of Hsien T’ien (Before Heaven) ching, qi, and shen. As we grow up we must then learn how to restore, gather, and transform them. They are then called Hou T’ien (After Heaven) ching, qi, and shen.

The secret of health, longevity, and immortality is not to damage the Before Heaven levels of ching, qi, and shen. If they are damaged, we must learn how to restore them. The next step is to gather these three and then transform them into an elixir that confers immortality.

It is worth noting that within the Tao Te Ching, Lao-tzu also speaks of Three Treasures. The treasures to which Lao-tzu refers, however, have to do with noble human conducts, not the forces of Hsien T’ien and Hou T’ien. In chapter 67 of the Tao Te Ching the term san pao is used; here Lao-tzu, speaking of the practice of wu wei (nonaggression), states that his three treasures are frugality, compassion, and mindfulness. This clearly expresses the idea of the restoration and gathering of ching, qi, and shen: Frugality can be viewed as conserving ching through lessening sexual dissipation and consumption of food; compassion can be perceived as the negation of the Seven Emotions so positive qi can be accumulated; and mindfulness can be considered the means for strengthening the mind and spirit (shen).

Ching

Ching, or essence, is normally translated as “sperm,” but this is incorrect in the Taoist context, as women also have ching. In the wider sense, ching is the energy inherent within the reproductive process, the “giver of life.” Ching is the reason we are born, and the lack of it the reason we die. Therefore, Taoists believe in both the stimulation and preservation of ching, for when the ching is strong, vitality and youthfulness remain. In the male too much dissipation will weaken the ching and thus shorten the life span and produce illness. In the female the goal is to end the menstrual cycle in order to regenerate the ching. In both cases the ideal is to return to the period in our lives when we either did not dissipate sperm as males or menstruate as females. This is obviously the period of our lives when we were at the peak of our youthfulness and vitality, or when we had, as Lao-tzu puts it, “the pliability of a child.”

It is not only sexual dissipation that damages ching, as Taoists believe that food and drink also play a major role. Food and drink enter into the bloodstream and thus affect the five viscera and seven openings, leaving behind many impurities. To the Taoist, excessive eating and drinking is a sign of unrequited sexual desire. Monks, especially celibate ones, had to be very careful about their diet.

But we must draw a distinction between excessive eating and obesity, as these do not have the same root cause. Obesity is a dysfunction of the Before Heaven Qi, meaning it is inherited. Excessive eating is a symptom of After Heaven Qi, meaning it is self-induced. Excessive eating and drinking is also considered the reason why a monk would enter a state of oblivion during meditation. (I think we’ve all experienced that after a big meal.) To the Taoist the end result of either excessive eating or emission is loss of vital energy. Great pains are undertaken to avoid this, so many male Taoists choose celibacy and eat only one or two meals per day. Others choose moderation and frugality in all these matters. The goal of all Taoists is to eventually live off the “wind and dew,” a poetic way of saying qi (breath) and saliva (the juice of immortality).

The term ching, as used in this text, has three definitions: the energy that is the essence of procreation, the substances of sperm and menstrual fluids, and, when ching has been transmuted into a spiritual energy, the Elixir of Immortality. The Taoist classics usually refer to these three manifestations of ching with the terms primordial ching, turbid ching, and true ching. All these ideas equate to what is called generative or regenerative force, in either the physical or the spiritual sense. To fully understand the term ching, as used in Taoism, we must understand not only reproductive secretions and sexual energy, but also transformative energy. In addition, the Taoist view of sexual activity falls into three categories: recreational, reproductive, and transformative. The restoration or repairing of ching falls into the third category, transformative, as only this confers health, longevity, and immortality.

The etymology of the character for ching gives many clues as to why Taoists chose this ideogram to represent the first of the Three Treasures.The main radical is mi, which symbolizes the idea of unhulled or uncooked rice, the natural state of the seed. Next to mi stands ch’ing, which depicts the green color of nature in the spring or growing stage. Ch’ing also stands for the white of an egg before the yoke develops. This ch’ing is made up of two symbols, sheng, meaning life and birth and tan, which represents both the hue of young, sprouting plants and the Elixir of Immortality. The symbol chu is often used as a contraction of sheng and tan.

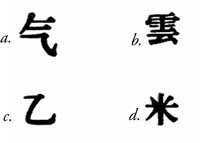

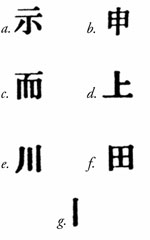

The etymology of the character for ching:

a. mi, b. ch’ing, c. sheng, d. tan, and e. chu

Taoists observed that the coloration of sprouting plants was identical to that of refined semen and vaginal secretions of accomplished cultivators. According to methods of the Taoist sexual yogas, when men retain sexual fluids and women regulate their sexual fluids, the sexual secretions of both transform into a form of the Elixir of Immortality and take on the coloration of sprouting plants. Thus, sheng and tan combined express the idea of “the Elixir of Immortality and the source of life.” Hence ching, and all its component parts, is the first and essential ingredient for creating the Elixir of Immortality.

Qi

Qi, or vitality, can be thought of as breath, vital life force, or an energy inherent within the body. The various uses and meanings of qi, from “breath” to “cosmic energy,” make it a most difficult term to define. The following definition will focus on personal qi, or, as traditional Taoists would call it, acquired qi or After Heaven Qi.

All the self-cultivation practices for developing qi come down to one fundamental aspect: the warming of fluids (blood, sexual secretions, and body fluids). In the I Ching this idea is depicted by the image of the sixty-third hexagram, After Completion, which is represented by the diagram of water (k’an)  over fire (li)

over fire (li)  .

.

Using self-cultivation practices, the blood is heated as it is stimulated through abdominal breathing. The blood then circulates more freely and begins warming the bones so that they produce more marrow, causing them to be more pliable and stronger. The heat generated through abdominal breathing will also warm the other body fluids and the sexual secretions (ching). When all this occurs, you can then sense the free circulation of blood and the movement of qi rising from the tan-t’ien (lower abdomen), as well as an increased sense of vitality, stamina, and lightness of body.

The human body, according to Taoist thought, contains five activities (Wu Hsing, the Five Elements). These are earth, wind, fire, water, and metal. Earth represents the bones and flesh; wind represents the breath; fire, the heat (qi); water, the blood and other body fluids (ching); and metal, the Elixir and spirit (shen). The process of refinement (lien) mentioned in many Taoist works is simply a matter of wind (breath) stimulating heat (qi), ch’i (fire) stimulating the blood (water), and blood (water) stimulating the bones and flesh (earth) to reach a state where the Elixir is formed and the shen is stimulated (metal).

After Completion image

To use another analogy, when the breath is full the qi is abundant, when the qi is abundant the blood will circulate, when the blood circulates the bones and flesh are nourished, and when the bones and flesh are nourished the Elixir can be formed.

From the above explanations you can see why qi is so difficult to define, as there are many facets of it. Qi is in the breath, in the heat, in the blood, in the bones and flesh, and in the Elixir.

The terms full, abundant, circulate, and nourished should be explained further. Full means that you are breathing with the entire body and that the breath is focused in the tan-t’ien, like a bellows. Abundant is the stage of experiencing heat throughout the body. Circulate is the stage which the qi is experienced in the tan-t’ien and is circulating throughout the body, like steam driving the piston of an engine. Normally, we must do something physical to increase blood flow, but in this case it is the qi circulating the blood flow. Nourished is the process whereby the stimulated blood flow and qi circulation begin permeating the flesh and bones with qi.

The etymology of the character for qi: a. qi, b. yun, c. chih, and d. mi

Etymologically, the character for qi is formed by two radicals. The first is qi, which represents several ideas, including cloudy vapor, aura, spirit, breath, air, and ether. The earliest meaning of this was “curling vapors that rise up from the earth to form the clouds above.” The radical is derived from two symbols, yun, or clouds, and chih, or the seed within man. The second aspect of qi is the radical mi, which is identical to the one used in ching. These combine to form “vapors that rise in the process of cooking rice.”

Shen

Shen, or spirit, is divided into San Hun (Three Spiritual Energies): ming shen (bright spirit), hsin shen (mind/heart spirit), and ling shen (immortal spirit). In the Three Spiritual Energies ming shen corresponds to qi, hsin shen to ching, and ling shen to shen. Accumulating the qi causes the shen to become bright, when the ching is restored the shen manifests itself, and when the shen is transformed it is immortalized.

This process, however, is a most difficult one to achieve, as we humans are affected by the Seven Emotions (Ch’i P’o), which negate the transformation of our hun shen (or San Hun). The seven emotions of happiness, joy, anger, grief, love, hatred, and desire all have negative effects on the self-cultivation of the Three Treasures, which in turn affects our spiritual development.

The Taoist believes that when a human being is born to this earth he or she inherently acquires a hun spirit and a p’o spirit. The hun spirit is a representation of yang, heaven, and immortality. The p’o spirit is a representation of yin, earth, and mortality. If during our lives we function totally within the Seven Emotions, then at death, when the hun and p’o separate, we will return to earth as one type of kuei (ghost). The kuei does not survive long and fades away to become a chi (dead ghost). The hun, on the other hand, is in a sense immortal, as it survives for a very long time, but it will eventually die if it does not unite with a p’o spirit and return to Earth to try again. If the feet are warm immediately after the point of death, then the p’o descends. If the top of the head is warm, the hun ascends, a telltale sign of whether the person’s spiritual practice bore any fruit. In brief, the only way out of this cycle is for the hun to undergo transformation as a true immortal.

When the shen is strong, the mental faculties are sharp and lucid. Shen is expressed externally through the eyes, revealing not only a deep and profound intelligence, but also a clarity and brightness of presence. A strong shen enhances the ability of sight and mental insight. These are all aspects of attaining ming shen.

When the shen can be retained internally and expressed externally, then it can be released from the body at will—an effect of hsin shen. However, this is a very difficult stage to pass through because the shen, as the years go by, becomes increasingly attached to the physical body. Usually, only in a dream state can the shen be released to wander about. This is not truly an effect of hsin shen. Only willed and conscious release is a mark of this achievement.

When we are young the shen is strong and not so attached to the body, which is why we can have so many flying dreams during our youth. We feel immortal. We do not truly accept or comprehend death, old age, and sickness. Time itself seems slower when we are young. Anyone can tell you how long summer vacation seemed to be in her childhood. But in old age we become more materially oriented, clinging to forms and objects in hopes of prolonging life and, ultimately, avoiding death. The mind becomes ever more narrow and unaccepting. Time begins flying by even more quickly. Days, months, and years are perceived as becoming shorter and shorter. An old Chinese saying relates, “Pay heed, young man, for in the twinkle of an eye you will be an old man.”

However, if the shen is made strong, death is no longer a concern, time slows down, and you become increasingly content with not only your lot in life, but with the world around you as well. All becomes tranquil. Like a youth, you are playful and at ease. Your attachment to the Seven Emotions ceases and the shen is free to interact with all the conditions in life that arise. As the Taoist puts it, “You will remain unmoved even if Mount Tai were to fall in front of you.”

The etymological derivation of the character for shen: a. shih, b. shen, c. erh, d. shang, e. chuan, f. t’ien, and g. the vertical stroke implying the connection between Heaven and Earth

The derivation of the character for shen is based on two radicals, shih and shen.

Shih is derived from erh, which is an old form of shang, meaning “heaven” or “the highest point,” and from chuan, which depicts those things that are suspended from heaven: the sun, moon, and stars. Combined, these radicals originally meant “the influx of things from heaven that reveal transcendent matters to humans.” Shen, the second radical, is also a derivation of t’ien, a cultivated field. The extension of the central vertical stroke implies a connection between Heaven and Earth.

[1.] . . . Which are elusive and obscure.

The Three Treasures are elusive, which means that seeking any of them as an object of possession will result in them eluding you even further. They are not tangible substances or objects. The problem is not whether they are real or unreal, but rather that our deluded minds cannot comprehend what Taoists call “the true emptiness of emptiness,” or as the Buddhist Heart Sutra puts it, “Form is emptiness, and emptiness is form.” To use an analogy, this is like a person wanting to scoop up in his hands the reflection of the moon on the water because he believes that the reflection is the real moon. The Three Treasures are like this also, because through the experiences of cultivating them we attach ourselves to the sensations, only to discover that these are but reflections.

The Three Treasures are also obscure, which indicates that using the rational mind to somehow experience and analyze them without self-cultivation will only lead to further distortion. To use the same analogy, this is like the man scooping up the reflection of the moon, but when his hands touch the water the image of the moon is distorted. What at one point seemed real is now revealed as an illusion. So the idea of elusiveness relates to our conception that these Three Treasures have form and are real; obscurity relates to our experience of seeing them as empty and illusory. These two extreme views are a natural progression for anyone who undergoes self-cultivation. We swing back and forth between views of real and unreal, bouncing off the extreme ends in hopes of finding the middle.

The Chinese characters for elusive and obscure are huang huang hu hu, which were borrowed from Lao-tzu in the Tao Te Ching. However, Lao-tzu used them in the singular, huang hu; the doubling is just to be more expressive. As a compound huang hu means “the unconscious,” “illusory,” and “elusive.” Lao-tzu used these two characters to express the idea of being confused about spiritual reality and unreality.

Only the person who looks up and sees the true moon, not the reflected image, can transcend and awaken to the illusion of the moon in the water. Likewise, the depth of our attachment to the illusory moon can become almost unfathomable, for one illusion may yet be distorting another illusion. For example, you may see a small moon in a small body of water and a large moon in a large body of water. Each moon is relative to the body of water it is reflected in. Therefore, if you never see the true moon, your perception will always be conditioned by the illusory, reflected moon.

The text begins by telling us that the medicine is for immortality, but then immediately warns us about the extremes of perception to which we may attach ourselves in trying to obtain these medicines.

2. Keep to nonbeing, yet hold on to being

And perfection is yours in an instant.

This is the secret of immortality, but it is very difficult to understand because we are caught in the realm of duality. We cannot perceive anything without simultaneously deluding ourselves with its opposite. For example, we cannot know white without comparing it to black. Everything is like this: male/female, up/down, hot/cold. This line is the one Lu Szu-hsing considers the most important. This particular verse is taken from the Tao Te Ching and has been interpreted variously.

In order to gain some understanding we must first examine the words being and nonbeing. In the Chinese the characters are yu (being) and pu yu (nonbeing). Yu means “to have” or “to exist”; pu yu means “not to have” or “not to exist.” From this the idea is “keeping to nonexistence, yet holding on to existence,” or “keeping to nonemptiness, yet holding on to emptiness.” Consider again the analogy of the person wanting to scoop the reflected moon from the water. When the person sees the moon reflected in the water and thinks it’s real, this person is attached to being.

Conversely, when attempting to scoop up the moon, this person becomes attached to nonbeing, or, maybe better said, “the illusion of being.” This is how we as human beings perceive everything, convinced that it is either real or unreal. But these illusions of being and nonbeing or reality and nonreality are just extreme views. In order to understand the verse, keep in mind that things are “not two.” We can’t really distinguish white without the concept of black, nor can we distinguish form without the concept of emptiness. This is the condition of the rational mind—it thinks in terms of opposites. But to the mind that enters the Tao, all concepts of duality are gone; everything is and becomes just One. Things are not either nonbeing or being. In relation to the Three Treasures they are neither nonreal nor real.

To really get to the heart of this verse we need to have some knowledge of both Taoist doctrine and self-cultivation practices, including meditation and the internal energy doctrines. To the Tao Shih (ordained Taoist) the text presents itself from a level that takes for granted his knowledge of such matters.

In very early Taoist practices there were two processes necessary for the attainment of immortality: yang hou (yang heat) and yin fu (converging the yin). This can be interpreted as the seen (yang) and the unseen (yin). Yang ascends and yin descends. Within fire there is heat and within water is coolness. These ideas are usually expressed in Taoism as Green Dragon, White Tiger, but the teaching has been perverted into a gymnastic series of breath control exercises and visualizations, ignoring its orginal context of developing ching and qi through specific sexual and contemplative practices. Almost all contemporary Taoist teachings are really just the process of yang hou—the process of accumulating and circulating qi. Yang hou is certainly a beneficial process, but it is only half the story.

In reference to Lao-tzu’s verse “hold on to Being,” yang hou is being. Yin fu is then “keep to Nonbeing.” Or as Lao-tzu also said, “From nothing comes something.” This means that when we cultivate the Three Treasures on the level of restoration, accumulation, and stimulation, we are only exercising the process of yang hou, which is the process of refining ching and transmuting qi. But when we refine the qi and transmute the shen, this is yin fu, or, as the text implies, instantaneous perfection.

How, then, do we “keep to Nonbeing, yet hold on to Being” in the same instance? How can we possibly embrace something and nothingness simultaneously? We can paraphrase Lao-tzu’s advice on experiencing or perceiving the Tao this way: If Tao cannot be seen, then stop looking; if it cannot be heard, then stop listening; if it cannot be grasped, then stop grasping; if you cannot think your way to it, then stop thinking. As long as the Tao is viewed as an object or goal, it will be forever elusive and obscure.

We are like a person who is under the illusion of being imprisoned and frantically attempts to pry open the door to escape. Yet in reality this person is just breaking into a prison. This is synonymous with the process of yang hou, for immortality is still not attained. My teacher, Master Liang, would humorously say, “Yang hou, is like eating; yin fu is like defecating. If you only practice yang hou, you will stagnate, maybe burn up. So don’t just eat and never defecate. Don’t just borrow and never lend.”

In Buddhism this same process was explained by Bodhidharma (Tamo) in the two works he left behind: Yin Chin Ching (The Muscle Change Classic) and Hsi Sui Ching (The Marrow Cleansing Classic). The Yin Chin Ching reveals the yang hou process; Hsi Sui Ching, the yin fu. But few are those who can truly explain yin fu in the context of attainment, for it is not a question simply of intellectual understanding, but rather of actual accomplishment—“uniting with the void.” The Hsi Sui Ching, in particular, is not written in the form of method, but rather in the perception of the effects.

Thus, this line about being and nonbeing refers to the Taoist goal of Returning to the Source and perfecting the Elixir of Immortality. Again using our analogy of the man scooping the moon from the water, in this instance he is no longer confused about the illusory nature of the two (being and nonbeing), as he now perceives the truth of the source of the reflected and distorted moon and is also able to look directly at the true moon (true nature). He is then instantly awakened and will never be confused by being and nonbeing again.

3. When distant winds blend together,

In one hundred days of spiritual work

And morning recitation to the Shang Ti,

Then in one year you will soar as an immortal.

Distant winds is a symbol of the ching, qi, and shen in the unrefined and unrestored state. Blend together means that they have been transmuted into the Elixir of Immortality. This stage of practice is also called “setting up the consciousness.” It centers on working with the light within the eyes, a result of having refined ching and transmuted qi.

One hundred days of spiritual work is a reference to the actual period of time for the ordination of a Taoist monk (Tao Shih). Within this time frame the would-be monk is required to cultivate within himself all the disciplines and moral deportments necessary for attaining immortality. One of these disciplines is what is commonly called “Virgin Boy Training,” which is one hundred days of preserving and restoring the ching. It is thought that if a person undergoes this training, his ching can be fully restored to the level of his ching prior to losing his virginity. It also reveals very quickly to the chief ordination monks whether or not this person is suited to spiritual and monastic life.

Another, far more profound viewpoint on this comes from the Me Wang Ching (Classic on Regarding the Pulses): “When the qi of the primordial spirit [yuan shen] has not yet been experienced, the idea is to perceive the ‘one thing’ that is like a great weight dropping directly down into the tan-t’ien to begin the completion of the Elixir. Afterward continue breathing and let it join naturally, yet constantly be mindful of it and not for a moment let it go. This is the true meaning of ‘one hundred days of spiritual groundwork,’ which is just a term for the art of perfecting the Elixir. One hundred days is only an approximate number.”

Recitation refers to memorizing the text and chanting every morning before the shrine of the Shang Ti, the Jade Emperor. For those with an inclination toward the ritual aspects of self-cultivation, the proper manner of performing the ritual is to place a likeness of the Jade Emperor or the Three Pure Ones in or above the center and back of a shrine table. Place lit candles and flowers to each side of an incense burner. In front of the incense burner place three small cups, offering tea, cooked rice, and fruit or vegetables in each of the cups, respectively. Make sure the area you recite in is quiet and clean. Place three lit pieces of incense in the burner. Bow three times, touching your head to the floor, each time reciting, “Praise to the Heavenly Ruler, the Jade Emperor, Highest Sovereign of heaven and all immortals.” When your head is touching the floor during each bow, mentally offer the flowers, candles, tea, rice, vegetables, and incense to the Jade Emperor, visualizing yourself before him in his heavenly palace. Offer these things in hopes of receiving an auspicious response to the recitation of his scripture. During the entire ritual, keep a reverent and quiet mind. When done reciting, bow three more times. Finally, light three more pieces of incense and place them out-doors either in a burner or in the ground. Bow three times at the conclusion of each recitation.

Further discussion on recitation and memorization is provided in the commentary on the last line of the text (see page 151).

Shang Ti is a reference to both the Jade Emperor and his entire court of celestial beings. When they witness the monk’s sincere practice and devotion to the attainment of the Way, they are moved to lend spiritual aid to the future immortal. In Taoism there is a saying that relates to this: “When a person finds the Way, heaven is gentle. When the Way is not found, earth is harsh.”

Then in one year you will soar as an immortal: The Taoist believes that it takes a human being about one year to enter this earthly realm and that it should take no longer to become an immortal, as both are just a transformation and birthing process. Another interpretation of this line is, “In one year an ascending immortal will appear.” A spirit guide will come to aid the cultivator at a certain stage in his development in order to help him past some very formidable obstacles.

In more practical terms, this verse is more likely a reference to the notion that it is the shen that is released from the physical body. Since the shen retains the image of the body, exactly as in the dream state, it only appears to be flying. Actual physical flight is an entirely different subject in Taoism, as there appear to be two distinct beliefs. Some accept only that it is the shen that is released and thus flies. Others accept the fact that it is the physical body that flies. We also find this idea in Buddhism, where rsi (immortals) are classified into five types: Heavenly Immortals, Earth-Wandering Immortals, Spirit Immortals, Sky-Flying Immortals, and Ghost Immortals.

Flying or soaring, however, is an incidental word here in comparison to the word immortal (hsien jen). The term has such wide usage in Taoism that it is difficult to assign to it a particular meaning. It has been used posthumously for many sages and yogis, and is awarded as an honorific to those of old age. But no matter the usage, to be an immortal has always been the goal of Taoists. Whether immortal meant actual physical, flesh-and-blood transformation to eternal life, the immortality of the hun shen, or extraordinary long life, the idea of immortality permeates all of Taoism.

Immortality is divided into three categories, or grades of accomplishment. According to Ko Hung, immortals of the highest grade can make their bodies ascend directly into the Void, and are then classified as heavenly immortals. Those of the middle grade retreat to the mountains to refine the Elixir even further, and are termed earthly immortals. The third type can be freed from the body only at death, yet the shen (spirit) remains intact, and they are called corpse-freed immortals. The highest grade becomes a heavenly official, the middle grade joins the earthly immortals on Mount K’un-lun, and the third grade enjoys longevity and te (virtue) on earth. Those who are destined to become heavenly immortals can achieve their aim even if serving in the military. Those who are to be earthly immortals can do so even if serving as government officials. The corpse-freed immortal, however, needs to first retreat to the mountains or a forest.

The Immortal Classic (Hsien Ching) adds that heavenly immortals can make gold from cinnabar, the Elixir of Immortality. Earthly immortals can only make use of herbs, mushrooms, internal calisthenics (for example, t’ai chi ch’uan) and breathing exercises (such as tao yin and qigong). Those of the third grade can maintain themselves only through the ingestion of herbs. However, the only requirement for the attainment of immortality lies in the following processes: the treasuring of ching, the circulation of qi, and the taking of one crucial medicine (the Elixir), which is produced from the first two. The secret is knowing how to treasure the ching and how to circulate the qi. There are numerous methods for both, and you must be able to distinguish the profound from the shallow.

Through purity the ching is treasured; through tranquillity the qi is circulated; through emptiness the shen is awakened. The ideas of purity, tranquillity, and emptiness are all within the mind. In Taoism the words bathing and washing are frequently used in reference to these three processes. Some later Taoists, especially those of the hygiene schools, adapted these two words in the names for specific exercises, but the meanings are quite different.

Something should also be said about the differences in the terms immortality and enlightenment, as so many of us confuse the two or lump them into the same basket. The highest stage in Taoism is called kung hsin (Nature Void)—sunyata, in Buddhism. This stage ends in the fourth heavenly realm above Mount K’un-lun but is still in the realm of form, as it is only the nature of voidness, not voidness itself. This is the level of heavenly immortals and is indeed enlightenment (chio), but not the level that Buddha attained and called annutarasamyaksambodhi, which leads to nirvana, wherein all realms are surpassed and extinguished. Therefore, in the context of Buddhist and Taoist definitions of awakened, the terms enlightenment and immortality are not always identical. Even so, kung hsin is a very high state of attainment. Earthly immortals do attain a state of awakening (wu), but are limited to realizations of this realm of form and the unrealness of it. Corpse-freed immortals are not necessarily awakened but do acquire a great deal of wisdom. In brief, heavenly immortals are those who leave this earth and function somewhere within the Jade Emperor’s court, earthly immortals are usually referred to as True Men (Chen Jen), and corpse-freed immortals are those called Sages (Sheng).

Another problem is the magician-alchemist Taoists who sought immortality only through the transmutation of base metals and herbs and other plants. It is not known if such formulas really existed or worked, and if so, I would be hard pressed to understand how awakening or enlightenment could be a direct effect of such formulas. During the Sung dynasty Ko Hung himself struggled with this question, and even though he attempted to find formulas for such processes, he could never afford to complete them or trust them. Chinese folklore and Taoist lore are filled with aphorisms alluding to the existence and usage of such formulas, as well as numerous accounts of alchemists who died after ingesting some of these formulas.

As mentioned in chapter 2, becoming a heavenly immortal is not necessarily a process or effort of cultivation. Those who attain immortality do so through one of two ways. In the first, the alchemist cultivates the Elixir of Immortality and after ingestion is immediately transformed into an immortal. In the second method, a heavenly immortal confers the pill to a deserving mortal, who is then immediately transformed into a heavenly immortal. Taoism is filled with such stories, and has a long history of tales of even Hsi Wang Mu (Western Heavenly Mother), the sole keeper of the Peaches of Immortality, conferring her immortality fruit to deserving mortals. Conversely, all earthly and corpse-freed immortals had to apply self-effort, receiving no aid from accomplished immortals.

4. The sages awaken through self-cultivation; Deep, profound, their practices require great effort.

Even if you were born with many inherent spiritual psychic and spiritual abilities, you must still cultivate yourself or you will lose them. No one is exempt. Anybody seeking to be an immortal must undergo the spiritual work, which is very difficult. However, the difficulty is really in the repetition of practices. The text states that the work required is deep and profound, meaning that it must be investigated and well contemplated through both study and practice. You can’t just pick up a book on Taoism, read it, and think you’ve got it. You must study intensely every day. Without patient effort and diligent study you cannot accomplish true understanding. A Ch’an adage reflects this well: “Cultivation is like climbing up a hundred-foot greased pole; enlightenment is synonymous with reaching the top of the pole and then making a great leap upward.” Climbing the greased pole takes great effort, but leaping from it takes not only great courage, but wisdom as well.