26

Journalism Ethics in the Moral Infrastructure of a Global Civil Society

Ethics is disturbing.

(Simon Blackburn, 2000, p. 7)

Nothing can be accomplished by denying that man is an essentially troubled being, except to make more trouble.

(William Barrett, 1990, p. 279)

The presence of the public in us depends on our willingness to recognize and to take responsibility for the other, that other person who appears to us, in our space, in our world, and whose presence cannot be ignored. It also depends on honesty and integrity, however pious this sounds, of the communications we construct for each other.

(Roger Silverstone, 2007, p. 39)

In the past decade or more the world of reporting events has expanded from the old categories of reporter, commentator, columnist (both serious and gossip), paparazzi, stringer, and journalist to include citizen journalist, blogger, news aggregator, tweeter, facebooker, youtuber, and mash-upper. Arguably, people referred to as “spinners” and “flacks” could also be added to these lists. These are not precise names, of course, and there is a fair amount of overlap in the activities of one sort of reporter and another. People who report events on Facebook, or via email, are likely also to be tweeters, YouTube users and possibly constructors of mash-ups. Some bloggers are also news aggregators or gossip columnists (Matt Drudge) or perhaps even journalists (HuffingtonPost). Some large media corporations (CNN, Fox) now invite citizen journalists to submit stories to their websites. Some print newspapers (e.g., The Washington Post) also employ bloggers. Some websites thrive on reports from their own constituents as citizen reporters (e.g., OhmyNews International from South Korea). How can any global ethical system be applied in such a complex and confusing context?

We must admit, first, the essential truth of Blackburn’s observation that ethics is disturbing, perhaps more so in an age of unedited reportage and the propensity to conflate journalism with reporting. None of us would be likely to challenge Barrett’s observation – at least on a rational basis – the foundation, rationale, or first justification for observation and reporting since newspapers gave up their singular attention to commerce and began to carry stories on politics, crime, and sensationalistic accounts of human depravity in the mid-nineteenth century. Of course, human nature being what it is (and I will leave that to each of you to define), it is always the “other” who is of interest. People object when the “other” is themselves – their privacy has been violated, their peccadilloes trotted out for the entertainment of the masses. Roger Silverstone’s (2007) suggestion that for people to embrace the public aspects of character requires that they take responsibility for the other means that they must, first, know of the other – as someone dependent, or owed, care. To do that, as he continues, requires honesty and integrity in what we say and hear about the other.

We might think of this as the first obligation, then, in this complex environment, for practicing life ethically. Seeing it in all reports of the other, regardless of source, is, of course, a chimera. Jean Baudrillard goes so far as to argue that it cannot be done. In our digitalized world, he says (2005), everything has become an image – even what we consider text on a screen (2005, p. 76). These images are no longer representational; they are merely information to be manipulated, processed, distributed, combined, and recombined. They tell no stories; they have no meaning. “It is this failure of representation which, together with a failure of action, underlies the impossibility of developing an ethics of information, an ethics of images, an ethics of the Virtual and the networks. All attempts in that direction inevitably fail” (2005, p. 78). So the question is, what must ethicists and journalists do – or what can they do, if anything – to assure that this obligation for honesty is met, given the complexity we now face, the essentially troubled character of humankind, and this new environment within which any global civil society must be constructed?

Baudrillard’s pessimism about the digital world is a good starting point for exploring the question of journalism ethics. This may seem odd, given his denunciation of the world as ethics-less, but his contention that our present context is one of information alone does provide a foothold. His characterization of our predicament is correct, of course, insofar as it applies to the challenge, even if we can (and should, or must) challenge his conclusion. It is not merely his pessimism that should give us pause, but also his implicit denial of the possibility for a robust ethical response to this environment. The human concern for ethics has too long a history to be dismissed so easily. So this essay will attempt to make a case for ethics in an unstable information-laden digital world.

First, let us hear Baudrillard’s argument. As everything has become undifferentiated information, Baudrillard doubts that the world itself can be “reflected or represented; it can only be refracted or diffracted now by operations that are, without distinction, operations of brain and screen – the mental operations of a brain that has itself become a screen” (2005, p. 78). In other words, everything suffers distortion – perhaps entropy – in its display and human beings who use information systems (e.g., computer screens) do so on the terms of the screen. “Image-feedback dominates, the insistent presence of the monitors – this convolution of things that operate in a loop” (2005, p. 79). Everything, then, is duplicity – because nothing is true, or authentic, as represented in such systems we all lose our sensibility about what matters, what represents. The countryside becomes a landscape, merely a representation of itself – not merely on the screen, but in the physical world as well, as people become incapable of seeing the countryside for what it is. They merely see it within the context of the artificial construct we call “landscape,” based on the way that we have become accustomed to seeing it on the screen (2005, p. 79).

What we see on the computer screen, Baudrillard argues, is only a “machine product” – the products of a machine itself (2005, p. 80). “they are artificially padded-out, face-lifted by the machine, the films are stuffed with special effects, the texts full of longueurs [overlong passages] and repetitions due to the machine’s malicious will to function at all costs (that is its passion), and to the operator’s fascination with this limitless possibility of functioning” (2005, p. 80).

Baudrillard also denies that the Internet provides the “freedom” that is often claimed for it. He calls what the Internet provides merely simulation (2005, p. 81). Although people may have the illusion that they are interacting, he says, they are merely doing so “with known elements, pre-existent sites, established codes. Nothing exists beyond its search parameters. Every question has an anticipated response assigned to it. You are the questioner and, at the same time, the automatic answering device of the machine. Both coder and decoder – you are, in fact, your own terminal” (2005, p. 81). This, he says, “is the ecstasy of communication” (2005, p. 81). The computer is a “prosthesis” (2005, p. 82).

As to news/journalism/reporting, Baudrillard says we are hostages, “but we also treat it as spectacle, consume it as spectacle, without regard for its credibility. A latent incredulity and derision prevent us from being totally in the grip of the information media. It isn’t critical consciousness that causes us to distance ourselves from it in this way, but the reflex of no longer wanting to play the game” (2005, p. 84). At first blush, this argument appears to have a positive streak. People are not “totally in the grip.” However, what he really means by that is that, because we maintain a bit of distance from the portrayals we view, we are mere spectators of spectacle. We see what we see as mere observers, detached as a result of our own cynicism, not as a result of critical consciousness. So what appeared potentially optimistic quickly fades.

Finally, Baudrillard provides some perspective on morality – but again with a condemnatory spin. Since everything becomes an image represented on the computer monitor, Baudrillard is concerned with the nature of that image. He says (2005) that violence is done to images as we see them. They are exploited “for documentary purposes, as testimony or message,” they are exploited “for moral, political or promotional ends, or simply for the purposes of information …” (2005, p. 92, ellipsis in original). All images are thus illusions, destroyed “by overloading them with signification; we kill images with meaning” (2005, p. 92).

There are at least three points to be made about Baudrillard’s concerns. First, some of what he says has been argued by others, so his objections are not necessarily unique. The problem of news as spectacle, particularly, is a point of view that many critics of news – and particularly television news – have raised before.

Second, there is truth and reality here. It is true, I think, that many people have gone down the route that Baudrillard illuminates: they fail to maintain an arm’s length relationship with the data flow that emerges from their computer screens. They seek it out; immerse themselves in it, as some recent examples of Internet addiction or videogaming have demonstrated. According to research conducted in Sweden, immersion in violent video games can lead to loss of bladder control from stress activation of the vagas nerve or to symptoms similar to premenstrual syndrome (Hurtado, 2008). Internet addiction treatment centers have also begun operation in some countries, including the United States and the Netherlands (Clark, 2006). A Council of the American Medical Association recommended to that body’s annual policy meeting that video game addiction be added to the diagnostic manual used to classify mental illness (Tanner, 2007). In South Korea a 28-year-old man collapsed and died after playing a video game for fifty straight hours with few breaks, little food or sleep (“S. Korean dies after video games session,” 2005).

Third, although Baudrillard argues that the mutation of experience into data streams makes concerns for ethics meaningless, what he is describing actually calls for an ethical response from societies where unbridled freedom has provided the philosophical justification for death by cyber-immersion. It seems to me that one task for journalism is to respond to social changes that do fundamentally shift the terrain for the expression of humanity and engagement with technology, which – if we take Baudrillard seriously – is exactly what he is arguing about society.

So on what basis, or using what criteria, might we develop such an expression and engagement? Second, is it reasonable to expect journalism to take the lead in developing appropriate expression, or showing the way forward in engagement with technology? This is an especially pressing and difficult question to address given the collapse of journalism itself in the United States as a result of falling circulations and revenues and the rise of the blogosphere as an alternative to the professional press. It is doubly a problem because journalists are as likely to mislead or misinform the public about technology as a result of their own needs (or those of their sponsoring organizations) as they are to illumine. These are global claims, and they require some elaboration here.

The decline of the print media – especially newspapers – in the United States is perhaps so well known that it goes without saying (see Ahrens, 2009; “Charting US newspapers’ decline,” 2009; Henry, 2007; “Who killed the newspaper?” 2006). The Project for Excellence in Journalism’s annual report on the news media began its 2009 report by stating that “newspaper ad revenues have fallen 23% in the last two years…. By our calculations, nearly one out of every five journalists working for newspapers in 2001 is now gone.” It was not just newspapers. Local television news staffs “are being cut at unprecedented rates…. In network news, even the rare programs increasing their ratings are seeing revenues fall.” The ethnic press is likewise “troubled.” “Only cable news really flourished in 2008, thanks to an Ahab-like focus on the election, although some of the ratings gains were erased after the election.” Matt Cover (2009) reported, too, that an internal report within the Federal Communications Commission written by commissioner Michael Copps, examined “the decline of broadcast journalism over the past several years and [tried] to explain why traditional forms of journalism have declined while other, newer forms have been on the rise” (see also Merritt, 2005; Meyer, 2009; and Tunstall, 2008).

It is not just in the United States that journalism is thought to be declining. Graeme Turner (2005) has written about the decline, at least of current affairs journalism, in the Australian Broadcasting Company’s programming. Steven Barnett and Ivor Gaber (2001) also argue that political journalism in Britain is on the decline, not because of financial woes or the Internet, but because of “the culmination of a number of interacting structural factors over which journalists have little control (p. 2).” If such concerns are correct, then the conclusion reached by Daniel C. Hallin and Paolo Mancini (2004) is particularly worrisome: “A powerful trend is clearly underway in the direction of greater similarity in the way the public sphere is structured across the world. In their products, in their professional practices and cultures, in their systems of relationships with other political and social institutions, media systems across the word are becoming increasingly alike” (p. 2).

On to the second claim: journalists are as likely to mislead or misinform as to enlighten when it comes to technology. The advent of what I call “pre-news” as a form of reporting has become so ubiquitous that perhaps many people do not notice it. By “pre-news” I mean the reporting of what someone is going to do, or is expected to do, later in the day or the week at a press conference, or through a press release or some other form on a matter of public interest. This makes the actual event almost anticlimactic. The only thing to wonder about is whether the event will affirm what has already been reported. In the area of technology this type of reporting has figured greatly in the phenomenon of “vaporware,” promised software advances that either never appear or appear at later dates as originally promised or in forms other than those that were originally reported. J. D. Kleinke (2000) has argued that even the “health care Internet” is an example of vaporware. Robert Prentice (1996), reviewing the antitrust case United States v. Microsoft Corp., quoted Judge Stanley Sporkin, who noted “that ‘vaporware,’ the high-technology industry’s marketing ploy of preannouncing products that do not exist at the time of the announcement and may never come into existence in anything like their described form, ‘is a practice that is deceitful on its face and everybody in the business community knows it’ ” (p. 1; see also Haan 2003).

It is not just the hyping of software that results in journalistically reported misleading information. The advent of so-called “neuromarketing,” based in brain studies has resulted in a variety of claims about known functional brain centers that could be appealed to by marketing campaigns. Max Sutherland (2007) calls this “toutware.” Its impact is exacerbated by media “overclaiming.” “The media love sensationalist stories that can carry a headline like ‘Buy centre of the brain found.” As a result, journalistic reporting is prone to outstrip the scientific substance.” Peter Lunenfeld argued as early as 1996 that many technology theorists were prone to similar excursions, leading to “science-fictionalized discourse.”

The frames used by journalists to report about technology can also be misleading. Journalists often look for an on-going narrative within which to place a story. This provides a means to discuss a new development efficiently by placing it within a context with which the audience is already familiar. The “gee-whiz” nature of much technological development (or at least announcements of developments) provide one convenient hook upon which to hang a story. Another such device is placing a story within a narrative structure with mythical qualities. Peppino Ortoleva explains some dimensions of this activity in this way:

Technology has been able, in the age of the great faith in progress, to create a world wonderful and realistic in the same time, the world of the great Expos, in which things that were becoming part of everyday life were at the same time projected into the myth of unlimited expectations, in which each single achievement got its meaning (both intellectual and esthetic) from the great endeavor of creating a whole new world of shared welfare…. More recently, another myth has succeeded in creating a symbolic (and illusionistic) remedy to a real condition of meaninglessness: that of interactivity …. The idea of a “prosumer”, of the consumer of computing who is made an hero by the technology itself he/she uses, is a very interesting case in which a concrete phenomenon …. overlaps with a plurality of aggressive marketing campaigns (2009, pp. 5–6).1

Myths attached to the development of technology in the United States are not new (Dery, 1997, especially pp. 10–11). Leo Marx (1997/2001, p. 26) writes about the “ideology of progress,” an ideology that often leads to “the archetypal sentence: ‘Technology is changing the way we live.’ ” He refers to this archetype as hazardous. This is because when the word technology is used in that way, it becomes “hazardous to the moral and political cogency of our thought.” In the United States reports about the spread of technology are often sprinkled with phrases such as “the global village,” a reference to the ubiquity of connection to the world that has overstated the reality since it was coined by Marshall McLuhan nearly a half-century ago. Reports of how health problems are diagnosed using the Internet or mobile telephones are used to stop price gouging in Africa are not uncommon (see, for instance, Grady, 2006). However, research undertaken by the International Center for Media Studies (www.center4media.org) in several developing countries over the past two years suggests that for the poor of the world even the arrival of a new technology does relatively little to change their situation beyond enabling them to stay connected on an infrequent basis with relatives working in other countries. Although the reports of instances where new technologies have assisted the poor may be true, they mislead by suggesting that they are merely one or two instances among many that could be reported – and thus poverty or isolation is reduced on a global scale. To repeat and paraphrase Marx’s point: when such reports are made within a context of mythologies and are taken as archetypes of reality on a global scale, they are hazardous. They distort the moral and political convictions of our thought.

Journalists thus contribute to the data streams of everyday life, but how they report the facts, and the context within which they place them can both distort these streams. Narrative structures make certain demands on the nature of their reporting. Commonly held mythologies can provide easy interpretive structures that result in facile interpretations. The use of isolated examples or anecdotes as a way to humanize stories or to provide instances of impact can distort interpretations made by audiences and diminish very real problems affecting the planet. All of these activities, whether intentionally used or not, mislead audiences – or can do. They also diminish the reality – and thus, I will argue, the humanity of those outside the usual understandings of audiences.

What, then, should publics expect from journalists, and – more importantly for this essay – what makes these expectations legitimate, or defensible, in a globalized, yet fragmented, world? As Christians and Traber put it (1997) in their introduction to a book on ethics and universal values, “Communication ethics … has to respond to both the rapid globalization of communications and the reassertion of local sociocultural identities. It is caught in the apparently contradictory trends of cultural homogenization and cultural resistance” (p. viii). Christians himself offers the prospect that what he calls “proto-norms” as basic commitments (p. 6). Such norms would be to Kant (1998) a “categorical imperative,” or to others nonnegotiable principles or axioms (see Elliott, 1997, p. 81). The difference is that in Christians’ formulation (1997), these protonorms emerge from a kind of consensus among those who practice different religions, feminists, and the international community at large as evidenced in declarations on human rights (pp. 8–13). Universals are possible because, as Gomes (1997) puts it, “human beings are imbued with a moral conscience that determines their daily actions…. [They] are moral by their very nature” (p. 211).

This sentiment itself is not universally endorsed. Zygmunt Bauman (1993) does not disagree with the point that human beings are moral by nature, but he does object to the idea that any sort of universal values can be imposed or even articulated within vastly different societies. “No universal standards, then. No looking over one’s shoulders, to take a glimpse of what other people ‘like me’ do” (p. 53). His claim, instead, is that “Only rules can be universal. One may legislate universal rule-dictated duties, but moral responsibility exists solely in interpellating the individual and being carried individually. Duties tend to make humans alike; responsibility is what makes them into individuals” (p. 54). He continues, “one may say that the moral is what resists codification, formalization, socialization, universalization” (Bauman, 1993, p. 54). Morality, in the end, Bauman argues (1993), is “irredeemably non-rational” (p. 60) (All emphases in original).

This is because, as he puts it (p. 69), “reason is, by definition, rule-guided; acting reasonably means following certain rules.”

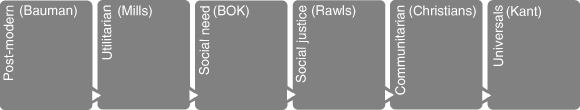

Figure 26.1 A continuum of approaches.

Between these two positions are a multitude of other approaches. We might put them on a continuum as shown in Figure 26.1.

This is by no means a perfect representation of ethical perspectives. Kohlberg and Colby (1987) and Noddings (2003) both would argue that ethics develops within people who are a society and would thus likely fit between Bok and Rawls. Bok (1999) argues that society cannot afford to accept untruths for their own sakes. Mill (1978) takes the position that it is the greatest good for the greatest number that must be the clincher when choices must be made. Rawls (1971) suggests that only when social, political and economic positions are put aside can anyone decide what the right course of action is. Kant demands that the categorical imperative be paramount in choice. So from the left to the right of this chart is a movement from innate, or emotional, morality (postmodernistic ethics) toward greater and greater application of rationality, a movement toward negotiated rules, then inviolable principles, determined by rationality or essential qualities (often based in religious traditions).

Is being human the same thing, then, as being moral? We all know enough about the atrocities visited upon both individuals and groups of people (think of Rwanda, Congo, Cambodia, Kosovo, Ukraine, Nazi Germany, etc.) to answer this question in the negative. There is nothing intrinsically moral about human beings. They may have a predilection (or merely a desire) to somehow make the “right” choice, but this begs the question – what is the source of that predilection? Perhaps it evolved as people discovered that working together made hunting easier or community life safer. Perhaps truth-telling became a norm because people found the consequences of lying potentially too horrible to contemplate. This would be the default position of those who will not accept the idea of a created order in which the expectations of the creator are hardwired into humanity. In either case, though, the exceptions to moral (or right) behavior are legion.

Given that reality, and the fact that none of us can be sure whether morality is hardwired, evolved, or developed within society, it is problematic to assume that any particular individual will act rightly, or even more to the point, altruistically, or as Daniel Bell (1976) puts it, with civitas. In many respects, however, this is the expectation that society has of journalists. The very notion of objectivity is premised on the fact that journalists will report news by putting their own personal biases (including moral biases) to the side. They will not be influenced by personal commitments, but examine and report facts independently of pressure, without subjective interpretation, and in a manner that is fair to all parties. In a real sense, without certainty as to moral standards or extant moral behaviors shared broadly across a society, the expectations of such reporting are ludicrous. Ethical codes written for professional societies of journalists, editors, publishers, and so on, all assume a rational perspective – they should be followed because they will result in trust, or profit, or professional status, provide for social acceptance of the product on offer. However, if universal principles cannot be trusted, or are negotiable, or if morality itself is not a rationality-based activity, then the basis for ethical expectations is fatally flawed. As Harry G. Frankfurt (2008) put it, “if we have no respect for the distinction between true and false, we may as well kiss our much-vaunted ‘rationality’ good-bye” (p. 66).

Yet the journalistic function in any society is too important to allow it to sink into a morass of subjectivity, relativism, or shifting allegiances. Hence the struggle among philosophers, moralists, theologians, and sociobiologists to determine some basis for right behavior. If the Commission on Freedom of the Press was right (1947), then there must be some basis for determining the truth of events, campaigns, contexts and movements, for the press to accomplish its first task: “providing a truthful, comprehensive and intelligent account of the day’s events in a context which gives them meaning” (p. 20).

It seems equally far-fetched to tell journalists to do as they will and the public will sort it out. The expectation that in a contest between truth and falsity, truth will always win out (at least eventually) is as fatally flawed as that journalists will act ethically in a morally-perverse world. People tend toward reading, listening, watching, or searching for facts that affirm their prior beliefs (see Carey, 1989). They don’t go looking for demonstrations of their own mistaken intellectual or emotional commitments. What is more likely is that the middle ground of commitments wherein reasonable conversations can occur among those with different beliefs will shrink and information that is more outrageous or fanatical will flourish, drawing people to ever more extreme positions – and thus destroying any possibility of genuine dialog.

The argument that is made here is that the role of journalism must be to open up prospects for genuine dialog. This simple statement rests on a foundation outlined by James W. Carey (see Carey’s chapters on journalism in Munson and Warren, 1997) and others concerning the necessity for journalism to function in such a fashion in order that democracy might flourish. (After all, dialog is not required in a dictatorship.) Beyond that, however, is the assumption that if journalism does not pursue this role, the chances that civil society can develop or be maintained in places where it may be lacking are slim at best and likely to slide into barbarity at worst.

The implications of this are two-fold (at least). First, it is necessary that some institution act to protect the language of discourse. If those who seek power are allowed to define terms or concepts as they choose without being called to account for distortions, unflattering (to brutal) portrayals of others, or prevarications, legitimate genuine dialog is impossible. Journalists are in the best position to assure that this occurs. They have more day-to-day connection with publics than do other wordsmiths such as storywriters, novelists, screenwriters, magazine writers, or educators, so their influence is more crucial. Also, they are both obviously engaged in dealing with matters of public import (legislation, campaigns, movements, protests, meetings, stump speeches, debates, spin, advertising, public relations, etc.) than are others, and they do so not from a position of power-seeking, but from one of dispassionate observer, fact-checker, and analyst (at their best).

It is, of course, the power of the unembellished truth that is most useful to genuine, or authentic, dialog in the public sphere. It is what protects the language of discourse itself, and what provides journalists with their power as watchdogs over the contests between ideologies or partisan positions that are part of the public sphere. This unembellished truth can only be guaranteed by adherence to one overarching requirement: the practice of ethics.

The second implication concerns the practice of journalism under a regime of ethics. Ethics in this sense is not about what journalists should be doing to adhere to some set of professional standards nor is it fundamentally about journalists functioning in a particular way because doing so would enhance their credibility. It is more fundamental than either of these rationales. The reason underlying such an expectation of protecting the language of discourse and thus accepting the limitations of an ethical regime (whatever it is), is that it makes the public sphere possible. Other forms of information or opinion contribute to the public sphere, but it is journalism that assures that honest discourse occurs. It calls people to account for their claims and vocabulary. It explicates the institutional or historical memory that is assumed without defense or even accuracy. It compares and contrasts the implications of differing approaches to public policy. It holds participants in the public sphere accountable.

Being able to accomplish such tasks, however, depends on the perceived credibility of journalists and this, in turn, depends on the way that journalism is practiced and defended. If journalism is merely another input into the public sphere, perceived to be little different than that provided by bloggers, aggregators, public relations workers, advertising, political bombast, crackpots, conspiracy theorists, or the uninformed but opinionated masses who believe what they hear from such sources, then there is little reason to be concerned about journalism itself. Journalism is only valuable to the degree that it does adhere to ethical standards of one sort or another, enforces them within its fraternity, and defends them within the public sphere.

At a minimum the requirements for journalists (as opposed, here, to mere reporters) is that they would, as the Hippocratic oath puts it for physicians, “do no harm.” Of course the “harm” that journalists might do differs from that for physicians, who are to assure that whatever treatment they accord to a patient does not make things worse. In the symbolic world of journalism it would always be problematic as to how this same expectation might work. A person could ask, “worse for whom?” Or “define worse.” The practice of journalism, if practiced rightly, would often result in a worse outcome for someone. A politician whose sexual peccadilloes are exposed is probably worse off for the publicity. A corporation whose polluting practices are outed, likewise, would consider itself worse off than when it controlled knowledge of its activities. Liars and criminals often do not appreciate having their true motives or behaviors held up to the light.

So what would it mean to do no harm? Our most minimal expectations, I will argue, are that journalists adhere to what Clifford Christians (Christians and Traber, 1997) has called “protonorms,” those universal values that societies and religious traditions agree are basic and non-negotiable “in terms of our human wholeness” (p. 6). The most basic of these is acknowledging the sacredness of life (p. 12). Based on that protonorm, Christians argues, are the ethical principles of “human dignity, truth, and nonviolence” (p. 13). Every issue opened for public debate should then have particular questions answered: “Do they sustain life, enhance it long term, contribute to human well-being as a whole? The challenge for the mass media is not just political insight on the news and aesthetic power in entertainment but moral discernment. This is the discourse that irrigates public debate, refusing simply to focus on politics or entertainment per se but connecting the issues to universal norms, speaking not only to our minds but vivifying the spirit, grafting the deeper questions underneath the story onto our human oneness” (p. 15).

This is a good first step – but our expectations for journalism must go deeper. One might argue that these basics adhere to all public discourse, whether by journalists or not. The demand for truth-telling, for instance, is for Sissela Bok (1999) the most basic requirement for interpersonal relations. Living in a society where people cannot trust others to be telling the truth in conversation is unthinkable. Felipe Fernández-Armesto goes one step further: “It is, I think, impossible to be human without having a concept of truth and a technique for matching the signs you use to the facts you want to represent as true” (1997, p. 4). Not only that, but human beings, according to Fernández-Armesto, have an innate characteristic of seeking coherence (p. 31). “No people known to modern anthropology is without it.” Desiring either equilibrium or coherence (or both) within a society is what leads them to seek truth – the most important “contribution to equilibrium or particip[ant] in cohesion” (p. 32).

Even “sacredness of life” could use more precision. It is not merely a requirement that people’s lives be spared, or that journalists report on activities that result in the taking of life (criminal activities, terrorism, genocide, war, etc.), but also that torture be banned (Tesón, 2001, p. 381). Beyond that are so-called “second-generation” human rights, rights that adhere to humankind by international agreement, that are part and parcel of definitions of a fully human life, although the lack of them may not, in itself, threaten the basics of human physiology. These include the “right to physical integrity, the right to participate in the election of one’s government, the right to a fair trial, freedom of expression, freedom of association, freedom of movement, or the prohibition of discrimination” (Tesón, 2001, p. 381) All such rights must be part of moral discourse, according to Fernández-Armesto because such discourse must be universalizable (p. 385) to have any meaning in the international arena (or sphere) of human rights.

Although there may be differences of opinion concerning the basis of such rights (with Asians, for instance, objecting to the Western individualist notion of rights rather than rights located within the collective), beginning from a different foundation can sometimes lead to the same conclusion: “the Buddhist conception provides an alternative way of linking together the agenda of human rights and that of democratic development. Whereas in the Western framework these go together because they are both seen as requirements of human dignity, and indeed, as two facets of liberty, a connection of a somewhat different kind is visible among Thai Buddhists of the reform persuasion. Their commitment to people-centered and ecologically sensitive development makes them strong allies of those communities of villagers who are resisting encroachment by the state and big business and fighting to defend their lands and forests” (Taylor, 2001, pp. 418–419). This different conception is based in the “fundamental value of nonviolence” (p. 418).

So we much go deeper – beyond merely a Western conception of individual rights to be protected (whether that is the “civil liberties” under the US Constitution or various human rights accords signed in the international arena). Journalists must not only do their tasks with these basics in mind (“do no harm”), but also carry out their tasks in defense of community. This is at once both obvious and controversial. It is obvious within the Western journalistic tradition where journalists have a type of fiduciary relationship with the public: they are watchdogs of government, they expose corruption in high places, they represent the public’s interests when the public does not have the access to the information or individuals who can provide the truth on particular issues. However, it is also controversial, because a question can legitimately be posed as to what communities are to be protected. There are minority communities of Muslims, people of African descent (Africans themselves, Caribbean-Africans, African-Americans), Arabs, and indigenous peoples, and others in many Western countries. Outside the West there are tribal and clan groups, castes, people of European descent and indigenous peoples, refugees, internally-displaced persons, expatriate communities, and so on. So, what community?

The answer is complicated, as there are two distinct ways to approach it. One way is to say the answer is all communities and no single community. In other words, journalists should not see their task as representing merely the most oppressed, or poorest, or least engaged community that may exist within a given society. The people in such communities should be represented, of course, but not to the exclusion of other communities that may be wealthier, more engaged, or powerful. This would mean that all communities should be represented, but none preferred. However, there is a caveat to this approach. That is that the universals cannot be violated.

Journalists can only avoid violating universals if they are committed to traditional values within the journalistic profession – especially fairness, balance, accuracy, and avoidance of conflicts of interest. Journalists who fail to commit to these traditional values cannot be trusted in the public sphere. A corollary to these values is a commitment to social justice – a step beyond simple fairness. As Joseph V. Montville explains (2001), “in its most general sense, justice implies order and morality. That is, justice means predictability in the daily life of a community and its individual members and the observance of basic rules governing right and wrong behavior. Justice serves the interests of life and the advancement of the human species, because it is perhaps the most fundamental element of peace. [Peace and justice must be defined] as progress toward the optimum environment for the fulfillment of human developmental potential” (p. 129).

This wider commitment to social justice is an important obstacle (if a true commitment) to preventing domination of the public sphere by the privileged in society. This is – according to Rawls (2001) the “first virtue” of social institutions (p. 4). Privilege may come from the exercise of political power, wealth, notoriety, celebrity or status (based, for instance, on race or gender). None of these can be allowed by true journalists acting ethically to influence the types of stories reported, the approach to them, or the perspectives and facts included. If these factors do influence reports, then what the public sees is the same as what defines current political discourse: an overvaluation of “individualism, confrontation, hyperbole, winning, and entertainment, while [undervaluing] community, understanding, compassion, and information” (Allen, 2002, p. 98).

This responsibility implies that those who have achieved some prominence in society, whatever the reason, should have no more access to journalists than do ordinary people. It also implies that, although no quantifiable favoritism should be shown to those from nonprominent elements of society, that attention must be given to engaging them in the wider conversation within the public sphere that comprises society. This could be done, as Jürgen Habermas suggests (Allen, 2002, p. 112) by controlling the press to prevent it from forging relationships with society’s most powerful elements, but such an approach would elevate legal requirements above ethical responsibility. Seyla Benhabib suggests an approach that retains the focus on ethics – a “radically democratized, conversational” discourse ethics “rooted in the Kantian tradition of ethical universalism [that] posits an idealized form of practical reason that transcends cultural boundaries” (Bracci, 2002, p. 126).

These boundaries may be those from one society to another, but they may also be seen within a single society, as many cultures may exist within a single social corpus. These cultures may be defined by ethnicity, gender, age cohort groups, class, caste, and so on. If journalists can succeed in identifying and using the collective knowledge that exists within such cultures as part of the due diligence we should expect as they exercise their fiduciary obligation to the public, this would devalue notoriety and thus radically democratize the nature of the reporting they do to open up the social conversation on matters that affect the lives of everyone.

The second answer begins with the question: what is the role of the press – is it to represent the public’s interests or is it to invite them into a conversation? It can be argued either way, of course. The traditional arguments for the First Amendment – for instance, that the public has a right to know and thus the press’s access to information must trump other considerations (short of national security), or that the independence of the press is sacrosanct because it is a watchdog on behalf of the public, are both essentially claims that journalists represent the public’s interests. In such cases journalists act on behalf of the other, and remain apart from it (for instance, see Gurevitch and Blumler, 1977, pp. 280–281). As Martin Linsky put it (1988), “at least as presently organized and under its current conventions, the press is a substantial barrier to overcome in attempting to move toward a richer, more participatory, broader, more explicative dialogue on public affairs” (p. 211). Why? “Journalists and news organizations like to see themselves as observers of public affairs, not as participants in them.” So they must stay “independent” and potentially “irresponsible” (Linsky, 1988, p. 211). Similarly, McQuail’s (1977) characterization of mass media as an institution that “can help bring certain kinds of public into being and maintain them” also suggests the separation between journalists and citizens (pp. 90–91).

Contrast this with the expectations of journalists put forth by John Dewey and James W. Carey. Dewey (1954) in typically abstruse fashion argues that the American polity developed in a period characterized by intimate community life, but that much was lost in the expansion of the country to a continent-wide nation that led people to organize themselves into interest-based groups disconnected from one another. To create what he called the “great community” (itself defined by democracy) two things were necessary. One was interconnection among these groups via the transmission and circulation technologies of the modern age. The second was the intelligence generated by the social sciences applied in daily news reports by journalists who were free of the distortions created by interests of elites that controlled the press (Chapter 5). If journalists were choosing news voluntarily (for instance, in the interests of their audiences) rather than at the instruction of their money-driven producers, they would be acting morally (Dewey, 1960, p. 8).

Carey (1997), although building on the foundation of Dewey’s ideas, is more direct and expectant about the relationship of citizens and the press. He argues that the press that is independent of the conversation of culture would be “a menace to public life and an effective politics” (p. 218). He continues with the observation that the press and the public must be connected, that the press without connection to its public is a vacuous notion. “The notion of a public, a conversational public, has been pretty much evacuated in our time” (Carey, 1997, p. 218). “From this view of the First Amendment, the task of the press is to encourage the conversation of the culture – not to preempt it or substitute for it or supply it with information as a seer from afar. Rather, the press maintains and enhances the conversation of the culture, becomes one voice in that conversation, amplifies the conversation outward, and helps it along by bringing forward the information that the conversation itself demands” (p. 219).

In this perspective journalists are participants in the culture, representing, encouraging, including, questioning, agreeing or disagreeing, with the variety of opinions voiced by members of the public as concerns. They are not apart. They are integral, intimate with the public, using their positions as journalists to assist the public in its deliberations. It does not pander to their baser instincts, but elevates the conversation by adding intelligence that emerges in their examination of issues. These examinations are to uncover the various opinions, facts, allegiances, biases, and connections emerging in public consideration of issues relevant to their own wellbeing.

So, both the universal and the particular must inform the practice of journalists. Commitment to the universal establishes journalists as humane practitioners. Such a commitment would mirror the ethic of primum non nocere – “first, do no harm.” It sets journalists apart from those who are committed to an ideology, or political platform, or who pursue self-aggrandizement, in their communication practices. When these motivations are fundamental to communication, they allow rationalizations that justify lying, distortions, and – as Harry Frankfurt (2005) claims – the most dangerous of all, “bullshit.”

The particular includes commitments grounded in community-defined norms. In the United States, for instance, such norms would include the guarantees of the First Amendment, not merely for a free press, but for freedom of speech and association. It also includes expectations for social responsibility, the protection of minority opinion and whistle-blowers, and willingness to spend the time and finances necessary to get to the bottom of controversies, and economic, political, and social practices. It demands that journalists eschew the “partisanship [that] is unabashed on the Web, and increasingly on cable” and the “rise of niche journalism … taking place as old-line organizations more frequently chase tabloid melodramas” (Kurtz, 2009).

In other words, it is through the practice of ethics itself that journalists actually become journalists. Journalistic style has been compromised by the sheer number of news sites on the web (which has supplanted much of what people used to think of as news sources) and the different approaches taken to reporting on them. Different perspectives, uses of language (both descriptive and vitriolic), and attention to different types of minutia have all contributed to a confusion of reportage. How are journalists to be known – to be identified in such a chaotic environment? It is by their ethics that we will know them. Although there are ethical dimensions to such activities as blogging, they are not the same ethics as those that should define truly journalistic activity.

This does not mean that journalists will always get it right or that aspects of news will always be reported first or more completely by them. Sometimes other sources – in some cases, perhaps, hugely biased ones – may accomplish this. However, by putting ethics first, before economics, style, publisher demands, or personal predilections, journalists can reestablish themselves as worthy of public trust. Their activities will reflect public questions, concerns, and fears, their reporting will include the representation of all segments of the society, helping people to understand the “other side,” because journalists are representing the “other,” whoever that may be. News will not be dominated by sensationalism, elite pronouncements, angry retorts, vindictive comments, because journalists will see their ilk as anomalous, self-serving, or designed to throw true debate to one side in favor of peculiar biases or idiocies. What will matter is what those with whom journalists are participating within the culture are worried about or do not understand. This does not mean that the public’s own silliness or uninformed perspectives are the focus of journalism, because journalists should be elevating the level of public understanding and debate by providing the intelligence necessary to accomplish this. However, they do not have to assume that the President, for instance, or the Senate majority leader, or celebrities, are always the most knowledgeable, articulate, or understandable in the public sphere that matters. Their job is still interpretation and contextualization of facts, explanation, provision of multiple perspectives, but within a public arena of accountability to the common man. People should be able to see that journalists are on their side, are their champions, are concerned about the same things that they are. It is only through new vigilance in following the universals of ethics, and knowing intimately the community nuances that influence application of these universals within a particular context, that journalists can distinguish themselves from other reporters or writers and reimagine their function within a democratic society. It is only through such work that journalists will be able to see the value of their activities to the public that they should wish to serve.

Note

1 The allure of reporting “scoops” in technology for journalists can be seen in Valvovic (2000, pp. 4–5).

References

Ahrens, F. (2009) The accelerating decline of newspapers. The Washington Post, October 27. www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/article/2009/10/26/2009 (last accessed November 9, 2009).

Allen, D.S. (2002) Jürgen Habermas and the search for democratic principles, in Moral Engagement in Public Life: Theorists for Contemporary Ethics, (eds S.L. Bracci and C.G. Christians), Peter Lang, New York, pp. 97–122.

Barnett, S., and Gaber, I. (2001) Westminster Tales: The Twenty-First-Century Crisis in Political Journalism, Continuum, New York.

Barrett, W. (1990) Irrational Man: A Study in Existentialist Philosophy, Anchor Books, New York.

Baudrillard, J. (2005) The Intelligence of Evil or the Lucidity Pact, (trans. Chris Turner), Berg, New York.

Bauman, Z. (1993) Postmodern Ethics, Blackwell, Cambridge, MA.

Bell, D. (1976) The Coming of Post-Industrial Society: A Venture in Social Forecasting, Basic Books, New York.

Blackburn, S. (2000) Being Good: A Short Introduction to Ethics, Oxford University Press, New York.

Bok, S. (1999) Lying: Moral Choice in Public and Private Life, Knopf Publishing Group, New York.

Bracci, S.L. (2002) The fragile hope of Seyla Behnabib’s interactive universalism in Moral Engagement in Public Life: Theorists for Contemporary Ethics, (eds S.L. Bracci and C.G. Christians), Peter Lang, New York, pp. 123–149.

Carey, J.W. (1989) Communication As Culture: Essays on Media and Society, Unwin Hyman, Boston.

Carey, J.W. (1997) “A republic, if you can keep it”: liberty and public life in the age of glasnost, in James Carey: A Critical Reader, (eds E.S. Munson and C.A. Warren), University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, pp. 207–227.

Charting US newspapers’ decline (2009) www.guardian.co.ukmedia/organgrinder/2009/oct/28/us-newspapers, (last accessed November 9, 2009).

Christians, C.G. (1997) The ethics of being in a communications context, in Communication Ethics and Universal Values, (eds C.G. Christians and M. Traber), Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA, pp. 3–23.

Christians, C., and Traber, M. (1997) Introduction, in Communication Ethics and Universal Values, (eds C.G. Christians and M. Traber), Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA, pp. vii–xvi.

Clark, A. (2006) Detox for video game addiction? July 3, www.cbsnews.com/stories/2006/07/03/health/webmd/main1773956.shtml (last accessed September 24, 2009).

Commission on Freedom of the Press (1947) A Free and Responsible Press, University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Cover, M. (2009) FCC Commissioner circulates document on “The State of Media Journalism.” July 9, www.cnsnews.com/public/content/article.aspx?RsrcID=50761 (accessed July 14, 2010).

Dery, M. (1997) Escape Velocity: Cyberculture at the End of the Century, Grove/Atlantic, Inc, New York.

Dewey, J. (1954) The Public and Its Problems, The Swallow Press, Chicago.

Dewey, J. (1960) Theory of the Moral Life, Holt, Rinehart and Winston, New York.

Elliott, D. (1997) Universal values and moral development theories, in Communication Ethics and Universal Values, (eds C.G. Christians and M. Traber), Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA, pp. 68–83.

Fernández-Armesto, F. (1997) Truth: A History and a Guide for the Perplexed, St. Martin’s Press, New York.

Frankfurt, H.G. (2005) On Bullshit, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ

Frankfurt, H.G. (2008) On Truth, Alfred A. Knopf, New York.

Gomes, P.G. (1997) Communications, hope, and ethics, in Communication Ethics and Universal Values, (eds C.G. Christians and M. Traber), Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA, pp. 211–224.

Grady, B. (2006,) Wireless technologies help less developed countries grow. Oakland Tribune, March 12, findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_qn4176/is_20060312/ai_n16155359/ (last accessed November 20, 2009).

Gurevitch, M., and Blumler, J.G. (1977) Linkages between the mass media and politics: A model for the analysis of political communications systems, in Mass Communication and Society, (eds J. Curran, M. Gurevitch and J. Woolacott), Edward Arnold, London, pp. 270–290.

Haan, M.A. (2003) Vaporware as a means of entry deterrence. The Journal of Industrial Economics, 51 (3), 345–358.

Hallin, D.C., and Mancini, P. (2004) Americanization, globalization and secularization: Understanding the convergence of media systems and political communication in the U S and Western Europe, in Comparing Political Communication: Theories, Cases, and Challenges, (eds F. Esser and B. Pfetsch), Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, www.mediacritica.net/courses/491m/hallin.pdf (last accessed November 19, 2009).

Henry, N. (2007) The decline of news. San Francisco Chronicle, May 29, www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=c/a/2007/05/29 (last accessed November 9, 2009).

Hurtado, C. (2008) The real danger of violent video games, November 26, www.popsci.com/entertainment-amp-gaming/article/2008-11/real-danger-violent-video-games (accessed July 2, 2010).

Kant, E. (1998) Groundwork of the Metaphysics of Morals, (eds D.M. Clarke and M. Gregor), Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Kleinke, J.D. (2000) Vaporware.com: The failed promise of the health care Internet. Health Affairs, 19 (6), 57–71.

Kohlberg, L., and Colby, A. (1987) The Measurement of Moral Judgment, Volume 1: Theoretical Foundations and Research Validation, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Kurtz, H. (2009) Media notes: Howard Kurtz on the evolution of media in the awful aughts, December 28, The Washington Post, C01.

Linsky, M. (1988) The media and public deliberation, in The Power of Public Ideas, (ed. R.B. Reich), Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, pp. 205–228.

Lunenfeld, P. (1996) Theorizing in real time: Hyperaesthetics for the technoculture, Afterimage, 23 (4), p. 16ff.

Marx, L. (1997/2001) Technology: The emergence of a hazardous concept, in Technology and the Rest of Culture, (eds A. Mack), The Ohio State University Press, Columbus, OH, pp. 23–46.

McQuail, D. (1977) The influence and effects of mass media, in Mass Communication and Society, (eds J. Curran, M. Gurevitch and J. Woolacott), Edward Arnold, London, pp. 70–94.

Merritt, D. (2005) Knight Ridder and How the Erosion of Newspaper Journalism is Putting Democracy at Risk, AMACOM, New York.

Meyer, P. (2009) The Vanishing Newspaper: Saving Journalism in the Information Age, University of Missouri Press, Columbia, MO.

Mill, J.S. (1978) On Liberty, (ed. E. Rapaport), Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., Indianapolis, IN.

Montville, J.V. (2001) Justice and the burden of history, in Reconciliation, Justice, and Coexistence, (ed. M. Abu-Nimer), Lexington Books, New York, pp. 129–143.

Munson, E.S., and Warren, C.A. (1997) James Carey: A Critical Reader, University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, MN.

Noddings, N. (2003) Caring: A Feminine Approach to Ethics and Moral Education, 2nd edn, University of California Press, Berkeley, CA.

Ortoleva, P. (2009) Modern mythologies, the media and the social presence of technology. Observatorio (OBS*) Journal, 8, 1–12.

Prentice, R. (1996) Vaporware: Imaginary high-tech products and real antitrust liability in a post-Chicago World, Ohio State Law Journal, 57, Heinonline.org (last accessed November 19, 2009).

Project for Excellence in Journalism (2009) The State of the News Media 2009: An Annual Report on American Journalism, www.stateofthemedia.org/2009 (accessed July 2, 2010).

Rawls, J. (1971) A Theory of Justice, The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Rawls, J. (2001) Justice as Fairness: A Restatement, (ed. E. Kelly), Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Silverstone, R. (2007) Media and Morality: On the Rise of the Mediapolis, Polity Press, Malden, MA.

S. Korean dies after video games session (2005) August 10, news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/technology/4137782.stm (accessed July 2, 2010).

Sutherland, M. (2007) Neuromarketing: What’s it all about. The Inaugural Australian Neuromarketing Symposium at Swinburne University, Melbourne, February, www.sutherlandsurvey.com/Columns_Papers/Neuromarketing-What’s it all about- March 2007.pdf, (last accessed November 19, 2009).

Tanner, L. (2007) Is video-game addiction a mental disorder? June 22, www.msnbc.msn.com/id/19354827/ (accessed July 2, 2010).

Taylor, C. (2001) A World Consensus on Human Rights? in The Philosophy of Human Rights, Paragon Issues in Philosophy, (ed. P. Hayden), Paragon House, St. Paul, MN, pp. 409–423.

Tesón, F.R. (2001) International human rights and cultural relativism, in The Philosophy of Human Rights, Paragon Issues in Philosophy, (ed. P. Hayden), Paragon House, St. Paul, MN, pp. 379-396.

Tunstall, J. (2008) The Media Were American: US Mass Media in Decline, Oxford University Press, New York.

Turner, G. (2005) Ending the Affair: The Decline of Television’s Current Affairs in Australia, University of New South Wales Press, Brisbane.

Valvovic, T. (2000) Digital Mythologies: The Hidden Complexities of the Internet, Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, NJ.

Who killed the newspaper? (2006) August 24, www.economist.com/opinion (last accessed November 9, 2009).