29

Questioning Journalism Ethics in the Global Age

How Japanese News Media Report and Support Immigrant Law Revision

Immanent Nationalistic Views inside Modern Journalism

This essay discusses how “fact-oriented” conventional journalism ethics works to support the ideology and politics of “nationstate” by taking up a case study of reports on Japan’s policy on immigration. Timothy E. Cook described in his book Governing with the News: The News Media as a Political Institution “how the development of the current news media has always been closely fostered by practices and public policy, how the news media perform governmental tasks, how reporters themselves (like it or not) are political actors” (Cook, 1998, p. 164). He regarded practices, rules and conventions of news media as an “institution” and worked to strengthen the government policies, from the theory of so-called “new institutionalism.” Extending Cook’s argument, I argue here that the news media in Japan has been serving not only as a political institution, but also as a major factor in the politics of nation building in its modern history and thus experiencing difficulties adjusting to the globalization and change to a multicultural environment that Japanese society is undergoing.

My aim here is not so much to criticize the content of the reports themselves, but to examine the process by which nation-centered discourse overwhelms more liberal, pluralistic discourse which is indispensable at the time of globalization. The problem I identify here is that it is not, as is often believed in general, powerful conservative actors who silently manipulate public opinion from the shadows towards the formation of more nationalistic opinion; rather, it is those professional rules and ethics such as disinterested detachment, the separation of fact from opinion, and the balancing of claim and counterclaim that cause the media to turn their back on examining social changes and acknowledging the emerging needs of new members of society.

The Professional Ethics of Japanese Journalism

For the purpose of analysis, I identify two characteristics of Japanese journalism and its views on rules and ethics. These rules may also be observed in other liberal industrialized countries, but the nature and degree to which Japanese journalists comply with them institutionally and systematically are symbolic due to the history and structure of Japanese journalism.

First, the media coverage in Japan can be characterized by its impressively heavy inclusion of “official facts.” This is attributed to its exclusive Press Club System for newspaper and broadcasting journalists. A press club is a group of major news organizations, including national daily newspapers, key TV stations and wire services that belong to the Japan Newspapers Publishers and Editors Association. There are hundreds of press clubs nationwide, and in most cases, members are given space in government and industry buildings including those of the prime minister, the Diet, ministries, local governments, and police.

Press club journalists feel they are compelled to be loyal to their duties and report facts obtained from respective official sources. They are trained to stick to “objective reporting,” and not to express their “private” opinions – “not being aware that their objectivity is a politician’s subjectivity” (Uemae, 1982, p. 42). Furthermore, according to their ethical professional rules, all the official announcements, and all the statements by “accredited” and prominent sources connected to press clubs, should be covered immediately and “correctly,” and all of them should receive a timely follow up for impacts and reactions so that no single paper falls behind in coverage of any story. Criticisms that Japanese newspapers all look alike may be attributed to this rigid professional ethic. Additionally, because each newspaper publishes a morning edition as well as an evening edition and most readers subscribe to them both as a “set”, and as each morning/evening edition is printed in several versions to include corrections and additions, journalists are required to update their information constantly until their final version is finished.1 This means at the same time that a majority of Japanese reporters work uninterruptedly throughout the day to keep up with their “latests” so that they can use the most up to date information. The “professional ethics” and working environment of Japanese journalists are designed for total devotion to following up “just facts.”

Unfortunately, however hard-working they are, Japanese journalists more often than not skip or neglect reporting some of the important issues. It is said that their news standards have become too mechanical to recognize new phenomena that utilises journalists’ own definition and interpretation. More often than not they become parochial in judging what is important to society at large due to limited capacity for reflection after long working hours. Consequently, the dose of nation-centric, if not always nationalistic, discourse receives high news priority while other issues get buried in oblivion.

Second, due to market forces, Japanese media have been increasingly required to reflect “public tastes” in selecting their topics and how they describe those topics. Down-to-earth, grass-root angles are theoretically justifiable if one considers that journalism has its mission to serve people’s right to know, but such a call would leave room for nation-centric, populisitc discourse. This is especially the case with Japanese media because Japan’s media audience consists mainly of those who can speak Japanese and identify themselves as Japanese.

It is no doubt that such a “user-oriented” tendency for the contents of mass media arose in tandem with the decline of the corporate media. Like other industrialized countries, with the Internet becoming an everyday tool to obtain information (often free of charge), many people, especially the young generation, turn to digital news source.2 In the face of a shrinking business, journalists are urged to be friendly and accountable to the public to win back their customers. Inside the industry, this call has often been translated into a normative form of being “reader-friendly” or “needs-sensitive” on the ground that journalists ought to serve society.

Keeping in mind these journalistic practices, rules, and ideology in Japan, I demonstrate how the revision of the Immigration Control Law, one of the most sensitive and new issues3 in Japan, was reported. In the following, I will first briefly explain the background of the immigration policy in Japan. After that I will touch upon the framing methodology I employed for the analyses. Next, I will present three discursive frames identified in the coverage of the revision of the Immigration Control Law. I will then examine how these frames compete with each other in the process of reporting and analyze the mechanism by which one becomes dominant. Last, I will reflect on the meaning of journalism ethics, rules, and practices in the rapidly changing globalized world.

Research Background and Method

On May 17, 2006, the Japanese Parliament approved the revision of the Immigration Control Law. This law was originally enacted in 1952 and provides the basic framework of immigration policy in Japan (Tanaka, 1995: 35ff). Although modeled on the system in the United States, this law from its inception was not designed to encourage migrants to settle in the country, to say nothing of including them as members of society. It can be said that Japan has kept its door shut to most migrants throughout its postwar history.

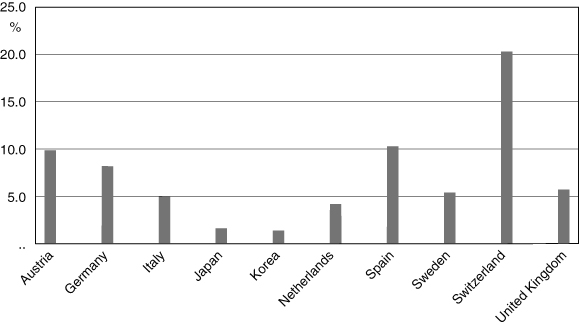

Some key statistical figures by the Immigration Bureau provide a broad picture of the movement and migration situation in Japan.4 The percentage of foreign residents against the total population remains around 1.7% at the end of 2007. As the international comparison figures in Figure 29.1 show, it is fair to state that Japan remains exceptionally cautious towards accepting migrants.

Figure 29.1 shows that Japan, together with South Korea, have a relatively small foreign population. Tanaka Hiroshi, urging a radical review of immigration policy as well as consciousness change on the part of the Japanese people, maintains that according to Japan’s way of thinking, its principle has been “no foreigners”, and those few foreigners who are accepted are treated “as exceptions” (Tanaka, 1995, p. 243).

Figure 29.1 Foreign nationals in selected OECD countries, 2008.

However, Tanaka saw a slight change in attitudes on the part of some Japanese when he wrote his book Zainich Gaikokujin. Ho¯ no Kabe, Kokoro no Mizo (Foreign Residents in Japan: Legal Barriers and Mind Gap) in 1995. Indeed, slight signs of change towards liberalization had been identified in some of the policy revisions made in the 1990s including banning fingerprinting of foreigners altogether and opening the door to foreign-born Japanese as an unskilled labor force.

With the enforcement of the most recent revision, however, all non-Japanese adults entering Japan are again obliged to be fingerprinted and photographed on entry. It is expected that the country will accumulate biometric data on more than 7 million people a year with this new enforcement. With this revision, Japan became the second country in the world after the United States to introduce the system of requiring visitors to give biometric information on entry.

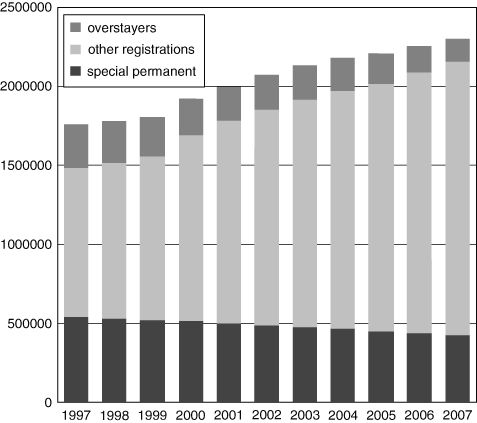

Many activists and scholars see this new revision as anachronistic against the tendency toward liberalization since the late 1990s, however modest that tendency may have been in its scale. It is estimated, for example, as of the end of 2008 that some 2 266 000 people from overseas live in Japan. Of them 2 152 973 are registered and 113 072 (as of January 1, 2009) are undocumented foreign residents. Some 430 000 foreign residents have a status of residence called “special permanent resident.” These residents are people, and their offspring, who were forced to migrate to Japan from Korea and China which were colonized by Japan before 1945. Altogether, the number of foreign residents has steadily increased, especially since the late 1980s as Figure 29.2 shows. The number of registered foreign residents has hit a record high.

Figure 29.2 The number of foreign residents in Japan 1997–2007.

Therefore, ever since the government first proposed revising the law, experts and NGO leaders have been very critical about this change. Even some conservative politicians and bureaucrats were skeptical about whether such tightened border control should be implemented in Japan since it totally goes against the borderless age we are in.

On the other hand, the government explained the necessity of this revision citing two reasons. One is to reduce visa overstayers who are believed to contribute to the rising crime rate and general deterioration of public security in Japan. The government, therefore, sought support for revision of the law on the grounds of maintaining “the people’s life and security.” This argument was in line with the action plan adopted by an initiative under Prime Minister Jun’ichro Koizumi in December, 2003 to reestablish Japan as “the safest country in the world.” This action plan aimed to halve the number of those entering the country illegally or overstaying their visas in the five-year period between 2004 and 2008.

Another reason cited by the government was “the war on terror.” In this respect, the government had already issued antiterrorism action plan in December 2001 at the Emergency Anti-Terrorism Headquarters established within the Cabinet Office under the top-down leadership of Prime Minister Koizumi. This plan included the blueprint of the revision in that it explicitly discusses the policy that requires all foreign visitors to submit biometric information when entering Japan. The stated purpose was to “forcefully advance comprehensive and effective emergency measures against terrorism.” This action plan also clearly states that an increase in the number of foreign aliens entering Japan is one reason why Japan had been transformed from a “peaceful country” into an insecure one. Thereby justifying the importance of the surveillance of foreigners entering Japan.

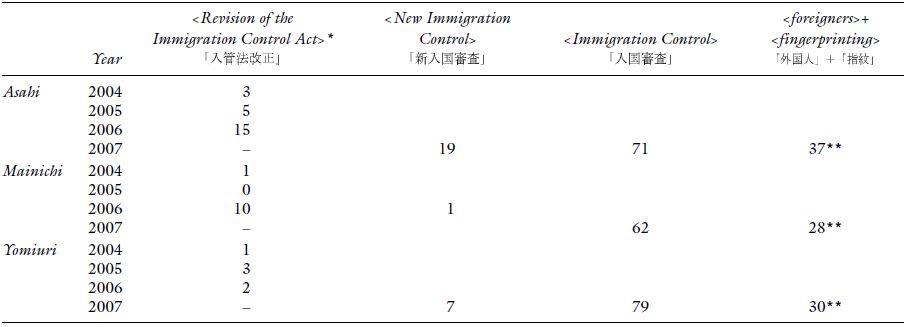

Table 29.1 The number of articles for analysis

The numbers include articles published in local pages of each national daily.

* The key phrase Revision of the Immigration Control Act sometimes refers to the 1989 revision. I read all the articles and omitted irrelevant ones.

**Only in November 2007 when the Act was enforced.

While investigating how the issue of the revision of the Immigration Control Law was reported I examine the development of discussions of the legal revision in Japan’s three major national newspapers: the Asahi Shimbun (daily circulation of 8 million), Mainichi Shimbun (6 million), and Yomiuri Shimbun (10 million).These dailies are considered to represent the liberal (Asahi and Mainichi) and conservative (Yomiuri) views of the nation and, as their circulation figures indicate, are well-read. Consequently, they set the direction of national public opinion on important political issues.5

For a broad overview, data was collected from the data bank on the Japanese press maintained by “Nikkei-Telecon.” I began with explorative investigations using several keywords and picked up at last three key phrases: “revised immigration law ( )” “new immigration law (

)” “new immigration law ( )” and “fingerprinting (

)” and “fingerprinting ( ).” These key phrases covered almost all the articles published during the period between January 1, 2004 and December 31, 2007. All the articles were also confirmed either from the newspapers themselves or from each paper’s reprinted compact paperback editions (called “shukusatsu-ban”). Data were also collected from local and regional newspapers, although there are few systematic search engines in this area. For a breakdown of these sources see Table 29.1.

).” These key phrases covered almost all the articles published during the period between January 1, 2004 and December 31, 2007. All the articles were also confirmed either from the newspapers themselves or from each paper’s reprinted compact paperback editions (called “shukusatsu-ban”). Data were also collected from local and regional newspapers, although there are few systematic search engines in this area. For a breakdown of these sources see Table 29.1.

The research employed media frame analysis. Media frame analysis has its theoretical origin in the concept of “frame” by Goffmann (1975). Goffmann’s frame analyses were conceived to identify and abstract rules as to how people organize subjectively their daily experience. He argues that frames bridge between social dynamics and individual actions and behaviors. Although he remained hesitant about claiming any connection between frames and social institutions or organizations, media frame analysts try to bridge the gap between individual understandings of events or texts and the organizational mechanisms of broader cultural, social meanings of discourse. According to Gamson, a frame is considered to be “culturally available” if there is any organization or advocacy network within the society that sponsored it (Gamson, 1992, p. 215). Robert Entman also emphasizes the power of culture in the production of frames: “Those frames that employ more culturally resonant terms have the greatest potential for influence” (Entman, 2004, p. 6). It is this cultural and social hegemonic power that I wish to problematize in the construction of media coverage.

News Framing of the Coverage on Revision of the Immigration Control Law

After having examined government documents, related literature and articles in the period from 2004 to 2007, I was able to identify the following three main discursive frames in newspaper reporting:

1 Critical interpretations focusing on the violation of foreigners’ human rights

2 Commentary on the government’s policies for “combating terrorism” and “counteracting the rising incidence of crimes committed by foreigners”

3 “Objective reporting” on implementation and execution

Critical interpretations focusing on the violation

of foreigners’ human rights

In this frame, the revision of the Immigration Control Law was reported from the standpoint that the human rights of foreigners in Japan were being violated since fingerprinting remains a key symbolic issue in the critique of discrimination and human-rights violations against foreigners in postwar Japan.

Japan used to take fingerprints as part of the registration process for all foreign residents, a policy which has been the subject of much controversy, especially among Zainichi Koreans. Historically, these Zainichis are one of the legacies of Imperial Japan. Tanaka discovered that the debate about whether or not to make fingerprinting obligatory for “foreigners” goes back to the late 1940s after Japan lost the war and its colonies. At that time, Koreans and Chinese abruptly became “foreigners” and continued to be deprived of their civil rights. Even their descendents, already in the second or third generations who have never been in their “homeland” and are not familiar with their “native” culture and language, were treated as foreign residents with the obligation of fingerprinting (Tanaka, 1995, 81ff).

In the 1980s and 1990s, the campaign against this obligatory fingerprinting of foreigners was led mainly by these ethnic Korean residents in Japan. After many years of campaigning, this ethnic group succeeded in abolishing the requirement on the grounds of human rights infringement. In 1999 the Alien Registration Law was further amended to eliminate fingerprinting of foreign residents in general. Following this change of law, Japan banned fingerprinting altogether in the year 2000.

In fact, in light of this historical background, the most recent revision exempted the so-called permanent residents including Zainichi Koreans, which makes up, 20% of all the registered foreign population in Japan. This has led to a consequence that the countermovement against this revision floundered.

Commentary on the government’s policies for “combating

terrorism” and “counteracting the rising incidence

of crimes committed by foreigners”

As previously mentioned in 2004, the Japanese government adopted an “Action Plan for the Forestallment of Terrorism,” which included revision of immigration legislation as one of its concrete goals for the prevention of terrorism. In reference to concerns that Japan had shifted from being a “society at peace” to an “unstable society,” this action plan also cited increased crossborder movement (in other words, the entry of larger numbers of foreigners into Japan) and especially the entry of illegal aliens and criminals as a cause of social instability. Both “combating terrorism” and “counteracting the rising incidence of crimes committed by foreigners” were thus included within the same framework in the revision of the Immigration Law.

This approach by the government was in close conformity with the public mood at the time. Even while the events of 9/11 were still fresh in people’s minds, there were reports in the media about terrorist acts by Islamic extremists in such places as Moscow and Madrid, and mention of the possibility that terrorists had entered Japan. These reports were combined with popular perception about the increased incidence of (nonterrorist) crimes by foreigners in Japan. As a result, this was the most easily accepted frame of discourse among the public in the years 2004 to 2006.

“Objective reporting” on implementation and execution

Much of the newspaper reporting on this topic gave much space on how efficiently the new immigration procedures were being implemented. Indeed, such reporting accounted for a larger volume of news than coverage of the debate on legislative revision. On the first day of the new law’s implementation, large numbers of journalists were mobilized to report intensively on whether or not the law was being successfully implemented. Much attention was paid to such “factual matters” as the new machinery installed at the passport control gates, the response of the immigration staff, and the length of time foreign tourists had to wait in line at the airports, typically with a photo of a foreign visitor putting his/her finger on the newly-installed equipment at the passport control. Such coverage surrounding a social event or the introduction of new administrative systems has been typically regarded as “news worth printing” in Japanese journalism. On the one hand, it could be understood as a fulfillment of journalism’s public duty in that it monitors achievements by the government and authority. On the other hand, however, it serves to divert attention away from the background and significance of the event by giving prominence to the minutia of administrative procedures (Hayashi, 2008). This narrowness of focus is all too typical of Japanese political reporting that adheres to the press club system (Krauss, 2000: 25ff, 53ff).

Altogether, in the course of the various phases of the revision process (planning, legislative debate, implementation), these three discursive frames appeared and disappeared – competing and interacting with each other. At any particular time, one of them may have come to the fore while the others retreated into the background. In the next section, I look in detail at this process of competition and interaction among the frames.

The Tradeoff between Foreigners’ “Human Rights” and “Combating Terrorism”

As already mentioned, the proposed revision to the Immigration Law was first incorporated as part of the “Action Plan for the Forestallment of Terrorism” finalized on December 10, 2004 by the government’s “Headquarters for the Promotion of Countermeasures against International Organized Crime and Terrorism.” At the time of the initial announcement of this plan, discussion focused mostly on the issue of human rights contravention. On December 11, 2004, for instance, Yomiuri Shimbun carried a 1200-character article explaining the plan under the following headline: “Terrorism Prevention Plan Countermeasures: Respect for Human Rights by International Standards and Adequate Explanation Required.” In its discussion of the plan’s significance, while making mention of the establishment of an underground Al Qaeda cell in the city of Niigata in May earlier the same year, it points out that human-rights problems would remain if the legal revision was adopted. The conclusion of the article reads as follows:

There is the possibility that parts of the currently adopted plan stipulating fingerprinting of foreigners and restrictions on the daily life of nationals will give rise to debate from the viewpoint of human rights. However, the reality of the approaching danger of terrorism cannot be ignored. Besides respecting human rights, the government also has a duty to explain and obtain the understanding of the people.

By portraying a state of tension between “human-rights” and “terrorism countermeasures,” the article presents revision of the Immigration Control Law as an issue of finding a balance between the two options. The inclusion of the words “respect for human rights” in its headline also casts doubt on whether terrorism countermeasures were a sufficient justification for the gathering of biometric information from all foreigners entering the country.

Asahi Shimbun’s article, published on December 8, 2004, almost at the same time as the prior Yomiuri article, was 600 characters long and bore the following headline: “Human Right Problems Remain: Government Issues Terrorism Prevention Action Plan.” “Human Rights” thus appears as the top headline. The lead immediately below the headline reads as follows: “Some measures are sure to lead to human-rights problems, and questions are likely to arise concerning the balance between counteracting terrorism and respecting human rights when it comes to concrete issues such as implementation and operation.”

Like Yomiuri, Asahi also presented “human rights” and “terrorism countermeasures” as being in a trade-off relation. This closely reflects repeated statements made by responsible government high-rank officials when appealing for support of the revision: “There is no time to lose before Al Qaeda makes Japan one of its targets” (Taro Kono, Deputy Minister of Justice); and “Terrorism is a major threat. It’s a question of balancing the weight of different values, so all we can do is to have some people endure” (Kunio Hatoyama, Minister of Justice).

When the revised law passed the Lower House of the Diet on March 31, 2006, Asahi Shimbun once again took up the issue of “balance” in its editorial, mentioning “human rights” and “the war on terror” as opposing values. The lead “Revised Immigration Law: the Merits and Demerits of Fingerprinting reads as follows:

The House of Representatives has passed the revised Immigration Control Law which stipulates the fingerprinting and facial photographing of foreign visitors to Japan. The stated purpose of the revision is to forestall acts of terrorism [as well as] […] counteracting illegal immigration.[…]

However, there is also deep-seated caution. The obligatory fingerprinting of foreign nationals residing in Japan was criticized as a violation of human rights and was abolished in 2000. […].

Security is of the utmost importance, but there remains a danger that Japan’s image may be seriously damaged. We urge the Upper House to consider the merits and demerits of this system from a wider perspective. (Asahi Shimbun Editorial March 31, 2006)

Thus, Asahi Shimbun pointed out the existence of both “merits” and “demerits” to the revised law. It maintained its noncommittal stance in this editorial, which is one of the few spaces where the newspaper has an opportunity to express its own opinions directly. “Forestalling terror,” “counteracting illegal immigration,” and the “affront to the dignity of foreign nationals” are each given equal prominence and the editorial concludes by simply observing that “revision of the law will have major effects.”

Meanwhile, Mainichi Shimbun refrained from taking its own position on the issue at all and strove instead to represent the opinions of numerous experts and people concerned. The frame of “human-rights violations” was particularly prominent in this debate, as the following extracts illustrate:

Fingerprinting in Japan is restricted to circumstances in which a person is remanded in custody as part of a criminal investigation or when a warrant has been issued. However, requiring almost all foreign nationals to give their fingerprints is going too far. There are even greater problems related to the maintenance and use of fingerprint information. There is the visible intention to go beyond the original purpose of counteracting terrorism and use this information in order to combat crime and control immigration. Since it treats all foreigners (including those free of suspicion) as potential criminals or illegal immigrants, the law lends itself to discriminatory practices (Nanba Mitsuru, Lawyer, Mainichi Shimbun, March 23, 2006).

Fingerprints are one of the most sensitive forms of personal information. Fingerprinting should be considered cautiously lest there be a danger of belittling privacy. We must avoid a situation in which the majority is forced to provide their fingerprints in order not to be severely disadvantaged by their inability to use automated gates (Hisashi Sonoda, Professor of Information and Criminal Law, Konan Law School, Mainichi Shimbun, March 28, 2006).

These comments were both published prior to the passing of the law in the Lower House on March 31, 2006. Just before the law passed the Upper House on May 1, 2006, Mainichi published a “debate” between the former chief of the Tokyo Immigration Bureau, Sakanaka Hidenori, and the deputy chairman of the Japan Federation of Bar Associations, Seiichi Ito.

In all these discourses in Mainichi, the word “fingerprinting” was laden with symbolism in the context of the “human rights” frame. This symbolism derived from memories of the highly significant human-rights campaign in the 1980s to abolish obligatory fingerprinting of resident foreign nationals.

In the final instance, however, both Asahi and Mainichi failed to adopt a clear position on the controversial revision of the Immigration Law and instead adopted the role of an “opinion forum.” This forum was structured according to the binary opposition between the “war on terror” and “human rights.”

Despite their slightly different distribution of opinions on the debate, all three national newspapers, Yomiuri, Mainichi, and Asahi demanded that their readers adopt the same basic approach of balancing the two frames of “national security” versus the “infringement of foreigners’ human rights through the compulsory provision of fingerprint data” at this early stage of discussion.

The positing of these two frames as mutually exclusive alternatives was even more pronounced in the regional newspapers. Shimotsuke Shimbun (a local newspaper based in Tochigi Prefecture) and Yamanashi Nichinichi Shimbun (a local newspaper based in Yamanashi Prefecture) both carried the same wire-service report about the revision of the Immigration Law, but the headlines they each added to the article suggest entirely “opposite” readings:

May 17, 2006

House of Councilors Justice Committee to Approve Revised Immigration Law Today: Aiming at Preventing Entry of Terrorists (Shimotsuke Shimbun, p. 5).

Fingerprinting Made Obligatory at Immigration Inspection: Revised Immigration Law to Pass the House of Councilors Justice Committee Today (Yamanashi Nichinichi Shimbun, p. 2).

These contrasting headlines indicate opposing editorial positions on the same report, one emphasizing the issue of “fingerprinting” and the other stressing “preventing entry of terrorists.” We need, however, to question the underlying assumption behind this binary opposition: Is the protection of foreigner’s human rights necessarily opposed to the protection of Japan from terrorist attacks? Lurking beneath the surface of the debate is an unspoken equation of “foreigners” with “terrorists.” This in the end is what provides the link binding together the various issues of “combating terrorism,” “criminal acts by foreigners,” “illegal entry,” and “illegal residency.” I will consider this further in the next section.

The Origins of the “Terrorists = Foreigners” Discourse

In the period between the publication of the 2004 government action plan and the passing of the revised law in May 2006, Yomiuri Shimbun only carried three articles on the issue. This is rather small in number compared to Asahi’s nine articles and Mainichi’s six. However, the Yomiuri editorial published on April 18, 2006 (while the bill was being debated in the Diet) contained the following very clear statement of opinion as the government started to articulate the significance and purpose of the revision:

The Revised Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Law has been passed by the House of Representatives and has been sent to the House of Councilors…. According to the Government, the revised law is “an avoidable measure designed to protect the lives and property of the nation. Besides forestalling acts of terror, it will also serve as a means to deal with crime by foreigners, illegal entry and illegal prolongation of stays.” The revised law is highly necessary and should be enacted in the current session of the Diet. (April 18, 2006 Yomirui Shimbun Editorial “Proposed immigration law revision: Move toward fingerprinting seen worldwide”)

In this editorial, there is no longer any mention of “human rights.” Starting with this article, Yomiuri abandoned the “human-rights” frame completely. The news angle has shifted instead to “combating terrorism” which the government exactly argued for in its proposal.

It is notable that the Yomiuri uncritically adopts the government line by listing “forestalling terrorism” and “crime by foreigners, illegal entry and illegal staying” as if they were self-evidently related. At the time of the revised law’s implementation in November, 2007, Yomiuri once again listed terrorism countermeasures and crime by foreigners in the same context and emphasized the concrete benefits of the law to persons with Japanese nationality residing in Japan. The headline and lead published by Yomiuri on this occasion was as follows:

Fingerprint data and facial photographs will be taken. The revised Immigration Law will be implemented on the 20th and the new immigration inspection system will swing into action. Its main objective is the prevention of terrorism and the entry of foreign criminals. If it succeeds, Japan’s reputation as a safe country will surely be enhanced. (November, 19, 2007 Yomiuri Editorial “Revised Immigration Law: Use fingerprints and facial photographs to improve public order”)

Yomiuri took over this unreflective identification of terrorism with foreign nationals from the government discourse contained in the 2003 “Action Plan for the Realization of a Society Resistant to Crime” and the 2004 “Action Plan for the Forestalling of Terrorism.” In contrast to Yomiuri’s lumping together of the issues of combating terrorism, crime by foreigners, and illegal immigration, Mainichi pointed out the separate nature of each of these objectives. While recognizing that the revised law would have some effect in combating these separate problems, Mainichi drew attention to difficulties with its implementation.

[…] However, it will certainly demonstrate its effectiveness against illegal entry on false passports. Of the 56,000 people deported last year, approximately 7300 had been deported previously. These are people who should never have been allowed into the country in the first place, and the system of immigration control was under constant criticism for being ineffective. (November 24, 2007 Mainichi Shimbun Editorial “New immigration law: Secure system desired”)

While it gives recognition to the effectiveness of the new law as a way of dealing with “illegal immigration,” the principal point of this editorial is to point out the need for urgent measures to improve more practical side of the issues such as data management.

Asahi raised doubts about the inclusion of immigration control issues together with “combating terrorism” despite the fact that initial discussion cited the latter as the purpose of revising the Immigration Control Law. It also contested the effectiveness of the new law in dealing with terrorist threats.

[…] However, some experts question their effectiveness in countering terrorism. A former chief of the Tokyo Immigration Bureau points out the following: “How can we check fingerprints when there is hardly any data of terrorist fingerprints in Japan? The first thing we need to do is establish our own data collection capacity.” (November 19, 2007 Asahi Shimbun Column “New immigration procedures starts tomorrow: Fingerprints and facial photographs collected”)

The above extracts, however liberal and critical they may initially appear, demonstrate that there has hardly been any debate on the definition of the word “terrorism.” There is an unspoken assumption that “terrorism” is an external problem created by organizations outside Japan such as Al Qaeda. This assumption is not, however, as self-evident as it may initially appear in Japan. Only the English-language Japan Times, whose readership consists mostly of foreign nationals resident in Japan questions the identification of “terrorism” with “foreigners.” This paper carried extensive discussion of the revised Immigration Control Law around the time of its passage through the Diet in, 2006, including the following:

Does anyone really believe that all terrorists are foreigners? The Tokyo subway sarin attack comes to mind (6000 injured, 12 dead), so does the bombings of Mitsubishi Heavy Industries in Tokyo in, 1974 (20 injured, 8 dead) and the Hokkaido Prefectural Government office in Sapporo in, 1976 (80 injured, 2 dead). The obvious prejudice here is palpable (Dioguardi, 2006).

The new law does not cover “special” permanent residents, i.e. Koreans and Chinese, which for some throws into question the whole basis of the fingerprinting requirement – preventing terrorist attacks – since Japan’s nearest threat is neighboring North Korea.

Exempting the very large North Korean community in Japan is an area of the law that some legal experts see as problematic” (Joseph, 2006).

The same August 22, 2006 article pointed out the vagueness of the law’s provisions even after deliberation in the Diet:

And despite plans to implement the changes to law from November 2007 some Japanese officials spoken to by The Japan Times suggest awareness of the law in government circles is limited. One Foreign Ministry official admitted: “We have not heard of that law yet. Are you sure it applies to permanent and long-term residents?”(Joseph, 2006)

To those who are to have their fingerprints taken, the “war on terror” and “foreigners’ human rights” are not in a situation of trade-off. There is no direct relation between terrorism and “crime by foreigners” and “illegal immigration.”

The desire to treat terrorism as something belonging to foreigners – that is, the culturally different “Other” – has already been pointed out by scholars such as Edward Said (1997). In the revision of the Immigration Control Law, the history of terrorist acts committed by Japanese citizens has been entirely forgotten. With the emergence of the frame treating the Immigration Control Law as a means of “combating terrorism,” “terrorists” came to be seen more and more like invaders threatening the internal peace of Japan from the outside. As a result, the focus of debate shifted almost automatically to the questions of how to prevent the entry of “illegal foreigners” and how to combat the growing problem of “crime by foreigners.”

Avid Coverage of Implementation

Another frame that was particularly important in coverage of the revision of the Immigration Control Law concerned issues of implementation and administrative management.

The “implementation and execution” frame functioned at first as a counterweight to the frame of “controlling terrorism and foreigners.” For example, at the earlier stage of the Action Plan, Mainichi published the following commentary on December 11, 2004, in which “terrorism countermeasures” and “implementation issues” are discussed together:

Since Japan has been named by Al Qaeda as a possible future target of attacks, the danger of terrorism for Japan has increased. However, systems have to be invented that would place restrictions on individual rights and impose extra burdens on individuals and businesses in order to strengthen the control against terrorism. As the government considers fingerprinting and photographing foreign nationals at entry and the creation of a data base, there is apprehension about possible information leaks and worry for the state becoming the collector of the “ultimate form of personal data.” (Mainichi Shimbun December 11, 2004 Commentary: “Terrorism prevention outline plan: Government adopts ‘Action Plan’ – Law to be revised in 2005 or 2006”)

In this article, the issue of personal data management is cited as a potential threat to individual rights. Rather than relying on memory of the struggle against the fingerprinting of foreign residents in the 1980s as Yomiuri and Asahi did at the early stage, Mainichi criticizes the revised law from the standpoint of personal data protection. The two frames of “terrorism/foreigner countermeasures” and “implementation and execution” are thus placed in opposition to each other. When, however, the law went into implementation in 2007 the debate shifted in the direction that “flawless implementation” would serve the purpose of terrorism countermeasures.

As I have already suggested, the prominence of this frame derives largely from the general understanding of the professional ethics of “monitoring power” and “objectivity” in Japanese journalism. As a fulfillment of this professional duty, journalists put their greatest efforts into observing the implementation of the law at airports around the country and interviewing entering foreigners to obtain their reactions. This becomes evident simply by examining the number of the headlines indicated in the Table 29.1 as well as the sheer quantity of column inches.

Unlike the case of the other two frames, all three national newspapers followed roughly the same line in their reporting on this third frame. This is true to the extent that they all carried very similar photographs of foreign nationals being fingerprinted and photographed at the immigration gates. Indeed, many journalists may have seen this frame as the one that matched the classical ethic of their profession most closely. For example, the previously cited Yomiuri editorial (2007, p. 3) that strongly supported the revised Immigration Law nevertheless contained the following demand to the government: “Operation will continue to require thorough consideration so that chaos does not occur as a result of system failures or excessive time taken to complete the procedures.”

By thus urging the government to be efficient and cautious in its implementation of the law, journalism is considered to formally fulfill its function in the narrowest sense of monitoring and criticizing those in power.

It might appear at first glance that the newspapers were fulfilling their role of scrutinizing the government by focusing debate on the condition of legal enforcement. However, this debate was premised on acceptance of the law’s existence, and little consideration was given to the background issues of “combating terrorism” and “dealing with illegal immigration” that lay behind the adoption of the law in the first place. By focusing almost exclusively on the efficiency of implementation after the law went into effect, Japanese journalism no longer questioned the justification and basis of the revision. This reflects the fact that the “implementation” frame was subsumed and assimilated into the justification for “terrorism countermeasures.”

On the day after the new law went into effect, Asahi carried a commentary article, “Start of the New Immigration Law: Caught between human rights and security – Increased staff at Narita Airport”, the lead portion of which is quoted below:

Amid concern about the invasion of privacy, the new immigration inspection system proclaimed as a measure in the “war on terror” went into operation on the 20th. At Japan’s number one gateway, Narita Airport, entering foreigners were compulsorily fingerprinted and photographed one after another. Asked to choose human rights or security, foreigners leaving the gates expressed various opinions about the new law, some in favor and some against. Some intellectuals issued warnings about the advance of social surveillance.

In this article, Asahi maintained its restrained position of favoring neither side in the balance between “combating terror” and “human rights.” The “implementation” frame also makes its appearance with the mention of the lack of trouble at the gates and reference to the opinions of various foreigners passing through. There was similar coverage in local editions of newspapers.

following introduction of the new immigration procedures involving fingerprinting and photographing, there has been a succession of mishaps in the taking of fingerprints […]. According to the Immigration Bureau, fingerprints could not be taken from a total of 21 people, due to reasons such as wearing away of fingerprints.

At Hakata Airport […] errors occurred in the cases of several tens of people when reading fingerprints magnetically. The procedure was repeated, but in the case of four people […] fingerprinting was abandoned and they were admitted at the discretion of the Immigration Bureau. Similar problems occurred at Narita, Chubu, Tokachi-Obihiro and Fukuoka. (November, 20th Mainichi Shimbun, “Immigration inspection: Fingerprinting of arriving foreigners, 21 people could not give fingerprints2)

On the 20th, the revised Immigration Control and Refugee Recognition Law was implemented, requiring all foreign nationals over the age of 16 to be fingerprinted and photographed, in order to preempt the entry of terrorists. At Narita Airport, 70 extra staff of the Tokyo Immigration Bureau were mobilized, forming a total force of 210, to guide arriving passengers and explain the procedures.

Some users had to repeat the procedures because reading of their fingerprints or photographs did not go smoothly. This caused arriving passengers to have to wait in line. (November 21, 2007 Yomiuri Shimbun, “Immigration fingerprinting and facial photographing made obligatory: 210 staff mobilized to guide and explain”)

As these articles illustrate, on this first day of the law’s implementation, all the major newspapers mobilized large numbers of their staff from branches all over the country to cover the story. The amount of labor expended in this one effort far exceeded what was used to cover deliberations on the law during its passage through the Diet.

Paucity of the Coverage

So far we have discussed three frames and the competition among them. However, there is another, perhaps most dominant, frame for the coverage: i.e. its paucity.

On June 6 2006, in the aftermath of the law’s approval in the Diet, Asahi reflected – somewhat apologetically – on the rather half-hearted tone of the debate, as follows:

Table 29.2 Coverage of the law revisions: Immigration Law vs. Education Basic Law searched on each paper’s data base for the period January 1, 2004 to December 31, 2007

| Revision of basic education law | Revision of immigration law | |

| Asahi | 1057 | 52 |

| Yomiuri | 604 | 58 |

[…]

The paucity of debate can be attributed to the understanding that “the problem has little to do with Japanese people.” Besides Japanese citizens, the revised law omits 470,000 special permanent residents as targets for fingerprinting.

A top official in the Ministry of Justice called this omission a “policy judgment.” Special permanent residents are citizens of North and South Korea who resided in Japan before the end of the Second World War or are descended from such persons. (June 6, 2006 Asahi Shimbun, “Immigration control: Differences in the deliberations between Japan and the UK on the provision of biometric information such as fingerprints and facial photographs”)

Asahi cites the exceptional treatment of special permanent residents and the perception that “it is someone else’s problem” as causes of the relative lack of debate compared to the case of Great Britain. Robert Entman (2004) claims that magnitude measures and helps determine a news event’s political importance: “the sine qua non of successful framing is magnitude” (Entman, 2004, p. 31). Such paucity may be a proof that the immigration issue is not a matter with cultural resonance in Japanese society. For example, there was far less coverage on revision of the Immigration Law compared with revision of the Basic Education Law, which was on the political agenda almost at the same time in the year 2006.

Figures show that the number of articles on revision of the Immigration Control Law remains as few as about 5% in Asahi and 10% in Yomiuri of the total headlines on revision of the Basic Education Law (see Table 29.2). It is understandable that domestic issues such as education reform have a higher news value in national media coverage. Nevertheless, the issue of the Immigration Law had to do with long standing political controversies regarding how open Japan can and should be to migration in the face of the increased border-crossing forces of globalization. Special permanent residents, of whom the majority are Zainichi Koreans, have long fought for their rights to stay in Japan without fingerprinting, and to them, the “revision” of this law appears nothing but anachronistic. However, because on this occasion, they do not belong to the concerned social group their voices were not raised against this change in the Law. Ultimately only around 60 articles were written in the full four years, which indicates that this issue never became a national concern, with the greatest weight being put on description of operational enforcement at ports and airports.

Conclusion

Through its “objective reporting” on the balance of debate between the demands of national security and the human rights of foreign nationals, the Japanese media failed to commit itself to the rights of foreign migrants. After all, any kind of advocacy is considered to be strictly inhibited in the world of journalism. As a result, the debate concerning the revision of the Immigration Control Law followed closely the discourse put out by “officially recognized” sources, such as government officials or intellectuals. In summary, among the “human rights frame,” the “combating terror frame,” and the “administrative implementation frame” within which the revision was reported, the last two were foregrounded.

Japanese journalists, who are mostly Japanese-speaking, monocultural people working lifelong for corporate media and living in the arena of nation-centric discourse, are not particularly sensitive to the need to listen to culturally and ethnically diverse voices. I conclude that the revised Immigration Control Law, which is targeted at foreigners who generally do not patronize the Japanese media and represent “total otherness” in their cultural and ethnic backgrounds, was practically irrelevant to the Japanese media due to cultural and linguistic barriers. My investigation confirmed that the newspapers all effectively gave support to the government policy line directly and indirectly through their journalistic practices and norms, whether they wanted to or not. So far, it would be fair to say that the direction of migration politics in Japan has been mostly determined by politicians and government officials with insufficient public scrutiny.

At least for issues that are not yet widely recognized as a social agenda within the national public sphere, it can be assumed that journalists select frames that are easy to understand to a wider audience such as war on terror or public safety so that their stories will be printed. The real challenge in the global age will therefore be to find out at which point and by which means new perspectives and values will grow to be an agenda for national debates and receive popular recognition in the world of domestic journalism.

Acknowledgments

I appreciate David Buist for his careful and competent translation and proofreading. I also thank Daimon Sayuri, news editor of the Japan Times for her numerous suggestions. This chapter owes much to the joint symposium by the University of Tokyo and the Japan Times Ltd. held in 2008.

Notes

1 Major newspapers belonging to the Japan Newspaper’s Publishers and Editors Association agree to set its final deadline at 1.25 a.m. for its morning edition and 10.00 a.m. for its evening edition. Newspapers cling to these deadlines strictly (and sometimes blindly) to keep the peace among them. A majority of reporters work until the last minute of these deadlines.

2 The total newspaper circulation declined from 53 669 866 in 1998 to 51 491 409 in 2008, a fall of about 4% in 10 years, according to Japan Newspapers Editors and Publishers Association. In addition, according to figures by Dentsu, Japan’s largest PR company, the share of newspapers in the advertising market has been falling continuously, from some 25% in the mid-1980s to 12.4 % in 2008, whereas that of the Internet has been rising steeply in the past five years. Its market share stands at 10.4% and it is expected to exceed that of newspapers in the very near future.

3 So far Japan’s immigration policy remains ambivalent. Some social and economic factors such as foreseeable labor shortages due to demographic changes are pushing some in the political and business sector towards a more open immigration policy. However, factors such as concerned popular sentiment about public security and growing apprehensions about international terrorism are prompting Japanese politics to adopt stricter immigration controls.

4 All the figures were cited from www.immi-moj.go.jp/toukei/index.html (accessed July 21, 2010)

5 Besides the large number of circulations, each newspaper company is operationally and formally associated with a large commercial TV broadcasting station.

References

Cook, T.E. (1998) Governing with the News. The News Media as a Political Institution, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Dioguardi, M. (2006) Japan Times, June 6, 16.

Entman, R.M. (2004) Projections of Power: Framing News, Public Opinion, and U.S. Foreign Policy, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Gamson, W.A. (1992) Talking Politics, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Goffman, E. (1975) Frame Analysis. An Essay on the Organization of Experience, Penguin, Harmondsworth.

Hayashi, K. (2008) Mass Media wo Shihaisuru “Saidai Tasū no Saidai Fukou”: Shokugyōrinri no Kentō to sono Sasshin no Kanousei [Innovations of Professional Ethics for Mass Media Journalism]. Ronza, July, 26–31.

Joseph, K. Jr. (2006) Japan Times, August 22, 16.

Krauss, E. (2000) Broadcasting Politics in Japan: NHK and Television News, Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY.

Said, E.W. (1997) Covering Islam: How the Media and the Experts Determine How We See the Rest of the World, rev edn, Vintage Books, New York.

Tanaka, H. (1995) Zainichi Gaikokujin – Hō no Kabe, Kokoro no Mizo, Iwanami Shoten, Tokyo.

Uemae, J. (1982) Shitenchô Wa Naze Shindaka, Bunshun Bunko, Tokyo.