Dried and pressed hop flowers waiting for brew day.

YOU CAN NO MORE BLAME CRAFT BEER DRINKERS FOR RAISING THE IPA ABOVE ALL OTHERS THAN YOU CAN BLAME HOPS FOR TASTING AND SMELLING TENACIOUSLY GOOD. WHEN THE CARBONATION AND ESSENTIAL HOP OILS ARE JUST RIGHT, A BEER’S AROMA CAN BURST FORTH UPON HITTING YOUR GLASS, ONLY FURTHER WHETTING YOUR APPETITE. YOU MIGHT EVEN SAY THAT A FINE HOPPY BEER IS A TEASE.

INTRODUCTION TO AROMA HOPS

Aroma hops are added to the boil after bittering hops. Despite the name, they contribute both aroma and flavor. By adding them later in the boil, the aroma and flavor compounds are retained. The closer to the end of the boil the hops are added, the brighter and more crisp they’ll be while also contributing more to aroma. Any hop variety can be used for aroma and bittering, but certain types have been bred for one or the other.

In this chapter, you’ll learn:

The different types of hops

Recommended hop blends

When to add hops

Hop flavor compounds

AMERICAN HOPS

American pale ales owe their hoppy beginnings to Cascade, which in 1972 became the first widely accepted American aroma hop. Innovation was slow for that generation of homebrewers, as most modern varieties didn’t appear until the 1990s.

Today, about thirty American varieties are available with aromas ranging from pungent citrus to delicate floral spice. Hops defy concrete characterization, and to a degree are like grapes, with good and bad years. However, the more established a variety, the steadier it becomes year after year. Reliable standbys, such as Cascade and Centennial hops, are bedrocks of consistent brewing.

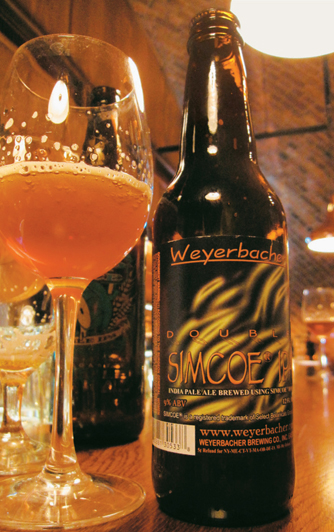

Weyerbacher Brewing’s double simcoe IPA is one of few single-hop double IPAs.

For lesser-known hops, most postharvest descriptions from distributors leave much to be desired. How helpful is it to know a new variety’s aroma is “mild and pleasant”? To help supplement your own batch-to-batch hopping experiments, try some of these hop mixes for flavor and aroma. |

||

Varieties |

Blend Ratio |

Character |

Amarillo and Simcoe |

1:1 |

Tropical fruit and pine |

Crystal (or Mt. Hood) and Simcoe |

3:1 |

Pine with herbal and floral hints |

Amarillo and Centennial |

1:1 |

Tropical fruit, lemon, grapefruit, and mango |

Centennial, Amarillo, and Simcoe |

1:1:1 |

Fruity, pine, and citrus |

Goldings and Target |

4:1 |

For English ales; earthy and spicy with hints of tangerine |

Saaz and Hallertau |

3:1 |

Pepper and floral |

Strisselspalt and Crystal (or Mt. Hood) |

1:1 |

Floral and citrus |

Blends courtesy of Stone Brewing Co.’s Head Brewer, Mitch Steele |

||

EUROPEAN HOPS

The classic hop fields in Kent, England, or Hallertau, Germany, grow beautiful, wonderfully subtle hops. Where American hops tend toward the big and bold citrus flavor, many German and English hops hold a more delicate spicy character. If blending both types of hops, and you should try it at some point, be wary of overpowering the milder hops.

If you’re recreating classic European styles, strictly traditional hops aren’t always necessary. Going back more than one hundred years, British brewers were known to employ American hops when the prices were right. Today, German brewers import about a third of their hops from the United States.

HOP TERRIOR

Hop distributors largely sell hop varieties as a commodity, with only a country of origin to distinguish them. Just like vintners might have a favorite hillside of grapes, brewers make appointments with growers to find the perfect crop and place orders for the year.

Homebrewers can’t always have the luxury of rubbing fresh cones between their fingers, but smaller independent growers may sell direct to brewers online in small quantities for homebrewing. Each farm’s soil, climate, and tending bring a slight, but unique, character to hops.

Farmers in Tettnang, Germany, celebrate their harvest with a Hops Queen.

The fall hop harvest in Washington State’s Yakima Valley, the largest hop-growing region in the United States

Hoppy doesn’t always equate to bitter beer. In fact, by pulling your IBUs from aroma and flavor additions (the final 30 minutes of a boil), you can create a smoother bitterness that lets the malt stand up for itself in the final beer character.

The name “hop bursting” was given by homebrewers, and the technique calls for adding a large charge of hops near the end of the boil. Some brewers prefer to distribute the hops over the final half hour their wort is on the heat. Others drop their hops in for the final 5 minutes. The essential rule to follow is that at least half of the IBUs should be drawn from the aroma and flavor additions.

POSTBOIL ADDITIONS

Once the heat is off, there are two popular spots to boost the hop aroma. In both cases, about 2 ounces (57 g) of hops will have a noticeable effect in a 5-gallon (19 L) batch of IPA.

HOPBACK

Immediately out of the kettle, before the wort even cools, brewers will pump the hot liquid through a hopback. Think of it as adding back hop aromas and oil lost to the boil. The device goes back at least a couple hundred years in brewing history and is essentially a sealed container with a filter that allows wort to pass through the hops, absorbing the fragrant oils. The wort would then be cooled and retain the aromatic compounds.

Some hopback advocates claim exposing the hops to hop wort is more sanitary, but hops have their own aseptic properties, and infection through hops is rarely, if ever, an issue.

DRY-HOPPING

This simple, but slow, process can potentially add a crisper, more pungent hop aroma than a hopback. Brewers typically add the hops for the last five to fourteen days of conditioning, but if that’s all the time your beer will mature, rack the batch onto the hops. Unless added to a sterile, weighted hop bag, your addition may float on top of the beer, not maximizing contact area. This is more a problem for whole-leaf hops.

Hop pellets spill over the top of a container during a dry-hop addition.

For an extra hop punch, try the technique of double dry-hopping. Split your dry hops into two equal charges. Then if, for example, you’re dry-hopping for ten days, add the first charge with ten days remaining and the second with five days remaining. The two levels of dry-hopping will add depth to your aroma.

HOP CHEMISTRY

Homebrewers can create more interesting beer if they understand the roles of the chemicals that make up those delicious alpha acids.

MYRCENE

Alpha acids and cohumulone help us understand bitterness (see chapter 2 for more), but myrcene is an easy indicator of pungent citrus and pine character. It’s one of four essential oils that contribute to flavor and aroma. Hop distributors will list the share of myrcene just like alpha acids. The classic noble hops of Europe are low in myrcene (about 20 percent of the oils), while stereo-typically rich American hops, such as Amarillo, Simcoe, and Cascade, are higher in myrcene (about 60 percent).

HUMULENE

Humulene represents a spicy, herbal central European character. Hops that are particularly strong in this sense, such as Fuggle, Saaz, and Hallertau, will have one to two times more humulene than myrcene.

SPOTLIGHT: HOW NEW HOPS ARE BORN

Every year, one or, if we’re lucky, two new hops varieties are planted en masse and make their way to your local homebrew store. These low numbers aren’t for a lack of effort. Every spring in the largest hop-growing region in the United States, the Yakima Valley, about 100,000 new varieties are bred through cross-pollination and planted with the hope that in ten years one of these plants will produce strong, pleasing, and consistent hops.

Over the first year, about half the breeds will simply die, while others are quickly eliminated for reasons such as poor disease resistance, weak cone structure, and bad yield. The following year, about one hundred potential varieties remain and the planting expands so farmers can begin to predict how they’ll act if widely planted. Some will develop strong onion or garlic aromas while others lack consistency. After five or six years, growers begin letting brewers experiment. If the feedback is positive, the next Simcoe or Amarillo may be born.

KNOWN AS THE “ALPHA KING,” NICK AND HIS MASTERY OF HOPS STARTED AT AN UNLIKELY BREWERY. BUT OVER THE LAST DECADE, HE DEVELOPED A CULT FOLLOWING FOR BEERS THAT ARE ALMOST BAWDY IN THEIR HOPPINESS.

WHAT WAS YOUR FIRST BREWING JOB?

The first job I could get was in Auburndale, Florida, alligator country, at the Florida Brewery, which made Falstaff, Gator Lager, Malta, and even Hatuey, the Cuban brand.

WOW, MALTA.

Yeah, unfermented [expletive] porter. You’ll put that in your book?

I MAY HAVE TO NOW.

And we were brewing with old cast-iron equipment.

I DIDN’T KNOW THERE WAS CAST-IRON BREWING EQUIPMENT.

Oh yeah, these guys didn’t care. The mash mixer, where you mash in, and the kettle were cast iron with direct steam injection. Metallic was the house character.

THAT THING MUST HAVE BEEN A LOCOMOTIVE.

I was 21, so sometimes I’d goof off and leave the kettle. Boilovers would shoot off a 20-foot rainbow of wort.

SO YOU MAY NOT HAVE TAKEN THE MOST PRIDE IN YOUR PRODUCTS?

When you went in the offices, you’d see 300 different cans of beer brands, but 200 of them were the same lager. And we brewed for ABC Liquors, a big chain down there. They had a light, an ale, a lager, and a malt liquor, but the ale and the lager were the same and the malt liquor had a handful of Melomalt added to give it a slight golden color. It’s hard to believe, but it’s a good experience when you’re 21.

I EXPECT THIS NEXT QUESTION WILL GET SOME CHUCKLES OUT OF YOU—HOW WERE HOPS REGARDED THERE?

I think we had two different kinds. Nugget hops and Saaz for special lagers like Hatuey. All I knew about hops was that there was a bittering kind and an aroma kind.

WHAT TURNED YOU ON TO HOPPY BEER?

Part of it was brewing all that crap in Florida. I had a Sierra Nevada in Tampa and I was amazed, then I started liking fresh German hoppy stuff.

IT SOUNDS LIKE IT GOT YOUR ATTENTION AND IMAGINATION. THEN WHAT?

This uptight German dude in Chicago had a job available at the Weinkeller Brewery. I’m like, you have all stainless equipment and I can make whatever I want? Ja.

I started bringing in all the Cascade, Centennial, or whatever freak-show new American hops we could get our hands on. But the German guy was so tightly wound he must have fired half of Chicago, and the place didn’t last long.

LET’S TALK ABOUT EXPERIMENTING WITH NEW HOP VARIETIES.

For professional brewers, it’s really important to go to the hops harvest in Yakima. Set up appointments, rub and smell all the hops, find out what field you like, what growing region you like, what variety. Find out which farms are growing experimental hops.

In 2010, we were one of eight breweries to get El Dorado hops. We used a control beer, like a pale ale or German altbier for a single-varietal batch to test it. We’ll do several batches like that a year with different and new varieties. Whenever we find a new hop we like, we jump on it and start making new stuff.

VARIETIES CHANGE CHARACTER EVERY YEAR.

I think Amarillo hops aren’t as good as they used to be; we’re phasing them out. Summit, in my opinion, used to be great when it was grown as a dwarf; now it tastes to me like onions if you go to a hop field. Centennial and Cascade are always solid, and more varieties are becoming more reliable every year. But you start by adjusting your hop blends to mimic the aroma and flavor you want, maybe mix in a hop like Warrior or Simcoe.

LET’S SAY YOU’VE GOT A HANDFUL OF HOPS, BUT THEY DON’T NECESSARILY SMELL LIKE WHAT THEY’LL BRING TO THE BEER...

They don’t, but for us, when we smell the hops we can visualize it. Any hint of dirt, onions, or bad aromas will be picked up later if you dry-hop. Not so much with kettle hops. The way we do it is hand to nose to kettle.

DO YOU HAVE CURRENT FAVORITE HOP VARIETIES AND OLD STANDBYS?

Our big three are Centennial, Cascade, and Warrior. We mix different high-alpha American hops to emulate what we want, basically.

ISOMETRIZED HOP EXTRACT: WHERE DOES THAT FIT IN?

You might look at it as an abomination by big breweries, ’cause they use gallons of that. But I think it’s a secret weapon for making double IPAs and giant IBUs without having the vegetable matter you’d otherwise need. It has its benefits.

I KNOW OF ONE HIGHLY SOUGHT-AFTER IPA THAT USES IT. DO YOU?

All our double IPAs. I think they have a place, but it’s an art to using them. I say why not try it out for anything over 80 IBUs.

IS THERE A LIMIT TO HOP AROMA? CAN YOU OVER-DRY-HOP?

Not to me. Yeah, I’m sure when you spend a lot of money making four kegs of beer, that might be a limit. It tastes the same as XYZ IPA, but you can brag about it on your menu and charge more at bars. The hop aroma wars are like World War II tanks: The Germans came out with a new panzer, and then suddenly the Russians have their new tank. I think the war’s ended, but some brewers are still going. I guess we’ve been there, done that, and know where our limit is.

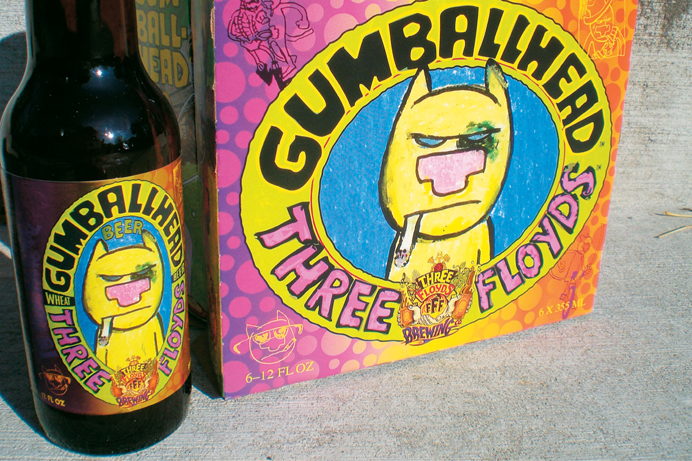

Three Floyds’ Gumballhead broke ground as one of the first hoppy wheat beers thanks to its use of Amarillos.

ALL THIS EXTREME BREWING HAS CERTAINLY PUSHED A LOT OF THRESHOLDS AND FRONTIERS. ARE THERE ANY LEFT?

Now the rush is to go back and make extremely sessionable, amazing quality beers like a helles lager. Not many people are doing that. I think most extremes have been met. Now I’m more happy to make a kickass lager and put it in a can.

WHAT DO YOU THINK ABOUT IDEAL WINDOWS FOR IPA OR PALE ALE, ABOUT HOW FAST HOPS DETERIORATE?

It’s a big issue for double IPAs. All these beer geeks want to drink it at two weeks old and say it’s garbage at five weeks. It kills me because real IPAs took three or four months to get to India and then they were mellow and rounded.

YOU DON’T MIND A LITTLE TIME ON YOUR BEERS?

I like Alpha King when it’s three months old, but to the new extreme geeks, that’s past its prime. They’re not looking for any other nuances besides getting kicked in the nostril by a pinecone. Even our double IPA at eight months, people say it’s crap. Me personally, I like stuff that’s aged a bit more.

SO WHERE DO YOU PUT AGING LIMITS?

I’d go by IBUs. A day for every IBU, if it’s bottled clean to begin with.

IS THERE A THRESHOLD AFTER THAT?

I think anything over 90 IBUs you can give at least half a year or a year. And don’t call it a drain-pour, just ’cause hops have mellowed a bit; it’s still a good, clean, bitter, bright IPA. Look for the other nuances in the beer.

DO YOU HAVE A PREFERENCE BETWEEN WHOLE-LEAF HOPS AND PELLETS?

We choose pellets for their stability. If we were closer to growers, we might favor whole-leaf. But for shipping and storing, pellets make more sense. Some of the greatest microbreweries out there use pelletized hops, so I don’t think there’s a disadvantage.

YOU’RE KNOWN MORE FOR NEW AMERICAN HOP VARIETIES THAN TRADITIONAL EUROPEANS. CAN EUROPEAN VARIETIES BE USED IN NONTRADITIONAL WAYS?

Oh yeah. We now make Blackheart, an English version of Dreadnaught Imperial IPA with Styrian Golding and East Kent Golding hops. What prevented us before is that European hops have been so expensive and iffy on consistency. But once you have a stable of American-hopped beers, why not go back and experiment with European and noble hops?

WHAT’S A BLEND OF AMERICAN AND EUROPEAN HOPS YOU ENJOY?

I’d use a small amount of Warrior for bitterness and then large amounts of English aroma varieties.