Just as beer has its barley and hop fields, honey has hives.

BEER HISTORIANS LIKE TO WAX POETIC ON THEIR BEVERAGE HAVING BEEN THE CATALYST FOR EARLY CIVILIZATION, BUT MEAD’S HISTORY TRACES BACK TENS OF THOUSANDS OF YEARS EARLIER AND IS LIKELY OUR EARLIEST FERMENTED DRINK. HONEY DISSOLVED IN WATER CAN’T HELP BUT FERMENT, AND ON A BASIC LEVEL, THAT’S ALL YOU HAVE TO DO—WATER IT DOWN AND WAIT.

Clover honey and the darker wildflower honey make an easy blend for mead.

Often mead recipes will look like a beer recipe: A base honey comprises about 80 percent of the sugar, with one or two other honeys added to complement the base flavor, like the malts in beer. Unlike specialty malts, though, most of the honeys you’d use in small doses could also be used for the base.

In this chapter, you’ll learn about:

Honey varieties

Mead brewing

Mead yeasts and fermentation

Conditioning mead

SELECTING HONEY FOR BREWING

Brewing malts and hops are relatively Standard from region to region. Honey, however, draws its character from the flora bees pollinate. An orange blossom honey will be citrusy as a result, and a desert honey will have a more earthy, spicy character.

Although that means there are few flavor standards for honey varieties, as with picking hops or grape varieties, as long as you have a quality product, there are no bad options. We recommend buying locally made honey, which can seem expensive, but simply tastes better and adds true local flavor to your mead.

In general, darker honeys have a richer, more nuanced flavor. Clover honey, which is stocked in every grocery store, is more basic and generic. Wildflower, which is highly dependent on its origin, and orange blossom honey are both reliable, easy-to-find options to begin making mead.

PREPARING YOUR HONEY

Mead makers should warm their honey in a hot box over a day or two before adding it to the brewing water. This dissolves any crystallization (caused by long storage) and makes mixing the honey in considerably easier. Cold honey added to heated water will sink to the bottom of the kettle, splashing the hot water and scorching the bottom of your pot. You can simulate a hot box by giving your container of honey a hot water bath in a tub of hot water from the tap. Ideally, the honey will slowly reach 110°F (43°C), at which point it’s ready to mix. Add honey as you would liquid malt extract, warm and with vigorous stirring.

YEAST

Most wine yeast strains will make fine mead under the right conditions, so choose one based on the fermentation temperature, honey strength, and desired sweetness or dryness. Taking a white wine yeast with a lower alcohol tolerance will leave a fair amount of residual sugar in a mead with more gravity than the yeast can process. Likewise, a strong champagne yeast will power through lower-gravity meads, leaving them bonedry.

HONEY TO MEAD

Step 1: Mix the honey and water. You should boil water, not honey. Actually, it doesn’t even need to be boiled. Bring your water to 180°F (82°C) and then turn off the heat. Once the temperature reaches 160°F (71°C), add your honey and let it sit for twenty minutes to pasteurize the must (unfermented mead) before cooling. Honey holds a lot of delicate aromas, so the less exposure to heat it has, the better you’ll preserve the flavors and aromas.

Step 2: Rehydrate your yeast by mixing it into a small amount of warm water (unless you’re using liquid yeast) as your must cools. You may also add a rehydration nutrient (different from fermentation-phase nutrients below) such as Go-Ferm with 1.25 grams for every gram of yeast.

Step 3: Aerate the liquid like you would wort. The yeast cells still need oxygen to work. Take your gravity reading, pitch your yeast, and wait for the first nutrient addition.

YEAST NUTRITION

Honey is relatively pure and sterile compared to most fruits or grains that are fermented. While this takes some stress off sanitation, it also means that beyond sugar, none of the necessary yeast nutrients, such as nitrogen, which you’d find on barley are present. Without small amounts of nitrogen, one of the most important nutrients, yeast won’t convert the sugar to alcohol.

Step 1: Add 1 teaspoon (4 g) of yeast nutrient (available at homebrew shops) near the end of the wort boil. Don’t add all the nutrient immediately because yeast would burn through it, speeding fermentation when you actually want a steady stream of sugar conversion from yeast for better flavor.

Step 2: Mead needs a number of nutritional boosts throughout fermentation. Add 1 gram per gallon (0.3 g per liter) of the nutrient, rehydrated, to the fermenter after the initial lag time (six to twelve hours before visual activity). Then add half that amount once a third of the mead’s sugar has been fermented. This promotes a slower fermentation than adding the nutrient immediately, but the yeast will remain healthy and active longer. Of course, before you add any nutrient, check the dosage instructions and the yeast’s nutrition needs. Some strains need more nitrogen than other.

Step 3: Aerate again. It’s common practice for some mead makers to aerate after fermentation has begun. Brewing will occasionally perform the same process for high-gravity beers, and the act further fuels the yeast while removing yeast-inhibiting CO2. Of course, oxidation becomes a worry whenever oxygen is introduced after yeast inoculation. If you feel your mead could benefit from an extra kick of oxygen, try aerating once after the first or second day of fermentation.

Each bee in a colony will produce a teaspoon of honey over the course of its life.

CONDITIONING

Mead is slow. There’s no way around it, so think of the beverage-to-be as an investment in your cellar like a great barleywine or imperial stout. Eight to twelve months is a typical maturation time for a traditional mead weighing in around 8 percent alcohol. Once you reach 12 percent and beyond, you can expect up to two years, maybe more, for the mead to mellow. A high residual sugar level will also increase aging time by as much as a year. The ideal conditioning temperature for a dry mead is around 60°F (16°C), but for a sweeter mead you can arrest fermentation by dropping the conditioning temperature to around 42°F (6°C).

OXIDATION

Long conditioning times can turn an unbalanced mead to a near work of art, but the longer it sits and the more it’s transferred, the more susceptible it becomes to oxidation. You might already recognize the signs of oxidation if you’ve had a vintage beer. At best, it creates a sherrylike character as ethyl alcohol breaks down to the fruity-tasting acetaldehyde. However, as the process continues, the oxidation flavors nose-dive into a realm of newspaper and nail polish remover.

Three steps help prevent oxidation:

Step 1: Age with minimal head space in your carboy. As yeast goes dormant and less CO2 is produced, it loses the ability to displace oxygen in the area above the mead.

Step 2: Store the mead cooler than you’d ferment it. This simply slows reaction.

Step 3: Adding Campden tablets, potassium (or sodium) metabisulphite, will bind oxygen to create sulfate and remove the free oxygen.

TYPES OF MEAD

Few mead makers actually focus on simple batches of fermented honey. Instead, there’s a rich history of styles, like in beer, calling in various types of ingredients for drastically different drinks.

BRAGGOT

This beer and mead hybrid is loosely defined as a mead that has malt and/or hops in the process. On one hand, you could make a braggot that pulls half its sugar from an amber ale recipe. You could also dry-hop a mead with floral hops, such as Centennial, to complement a floral honey. If you go this route, add up to 2 ounces of hops per gallon (15 g per liter), depending on how happy you want to make fellow hopheads. Other brewing spices are commonly used, added to the kettle while the must is hot.

A typical recipe will have a fairly even split of malt and honey, but keep in mind that barley has a richer character than most honey and can easily overpower and mask a wonderfully complex variety. Honey, per pound, contains slightly more sugar than base malt but ferments completely, whereas barley conversion relies on mash efficiency. To balance malt and honey sugar, use 1.5 pounds of grain for every 1 pound of honey (or 1.5 kg grain for every 1 kg honey).

When transferring mead (or any hard beverage), keep the transfer tube below the top of the liquid to avoid splashing.

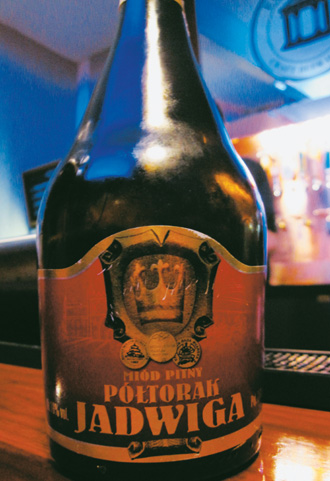

Brewed with “more honey than water,” Póltoraks like the Miód Pitny Póltorak Jadwiga drink like dessert wines.

FRUIT MEAD (MELOMEL)

There are generally even fewer rules to adding fruit to mead than there is with beer. A basic mead makes a great platform for interesting or particularly delicious fruit.

To let fruit, or any flavoring, stand on its own, use a milder honey, such as clover in your mead.

As little as 8 ounces (225 g) of fruit in a 5-gallon (19 L) batch will make a large flavor impact on mild mead. Larger additions, such as 1 pound per gallon (120 g per liter), would be appropriate for sweeter, high-alcohol (12 percent and higher) meads.

CYSER

A meeting of cider and mead, cyser often has the zest and fruit of a white wine, but with a distinct honey character. Like pyment (below), the two components are fermented together and conditioned like a mead. A common blend is 2 pounds of honey per gallon (240 g per liter) of cider. With no added water, this yields a starting gravity near 1.100.

Polish meads stand out for their simplistic, traditional recipes and colorful herbal character. Polish mead makers often age their miód in oak with local herbs for several years and use mostly acacia honey with some buckwheat honey. The varieties are broken down into four styles defined by their water content.

Name: Czwórniak

Water-to-Honey Ratio: 3-to-1

Water-to-Honey Ratio: 1.1

Approximate Final Gravity: 1.02

Strength: 9 to 11

Character: The lightest of the meads is regarded and enjoyed like a dry white table wine. It also can be added to hot tea or poured over ice cubes in the summer.

Name: Trojniak

Water-to-Honey Ratio: 2-to-1

Water-to-Honey Ratio: 1.14

Approximate Final Gravity: 1.04

Strength: 12 to 15

Character: This registers semisweet, is often aged for a few months in oak, and may have a fruit or herb flavor added.

Name: Dwójniak

Water-to-Honey Ratio: 1-to-1

Water-to-Honey Ratio: 1.21

Approximate Final Gravity: 1.09

Strength: 15 to 18

Character: Sweet and strong, this mead approaches port after several years of aging.

Name: Póltorak

Water-to-Honey Ratio: 1-to-2

Water-to-Honey Ratio: 1.25

Approximate Final Gravity: 1.12

Strength: 15 to 18

Character: The strength increases, leaving it around 16 percent with enough residual sugar to make this a fine dessert mead. It can be and is aged for decades.

If you want to try replicating these sugary wonders, try a small batch with honey, especially acacia honey from Poland, from a European food supplier. (Locust honey, which is widely available in the United States, is similar).

Fruit versions of these Polish meads will swap a third of the water for juice, and herbs are added to the boil (these are boiled, not just heated) and conditioning tank. Use a high-attenuating, alcohol-resistant wine or mead strain. Otherwise, follow the normal mead process and have a little extra patience for behemoths like these to mellow.

PYMENT

This variation of melomel is distinct for its use of wine grapes. Also, although fruit additions are regularly added to (but not limited to) conditioning tanks, the grape juice is fermented along with the honey.

A good starting point for making pyment is to use a sugar content blend of 75 percent honey and 25 percent of your favorite grape varietal. Most homebrewing stores stock wine ingredients, such as grape juice concentrates or, if you’re lucky, frozen grapes.

Pyment can be further dissected and becomes hippocras if spices are added. Historically, hippocras referred to a dry wine sweetened with honey and flavored with herbs, such as ginger and cinnamon, but today it is considered a type of mead. The flavoring doesn’t need to be anything special, as normal metheglin spices make a fantastic hippocras mead.

METHEGLIN

Metheglin is spiced or herb mead. The most popular infusions are similar to beer, with Belgian and winter spices such as cinnamon, vanilla, ginger, and orange peel commonly used. This style of mead is an opportunity to inject your favorite culinary flavors; nothing is off-limits. If someone can brew a garlic metheglin (and they have), don’t be afraid to try to make a chili-pepper mead (Capsicumel) with a half pound (225 g) of jalapeños.

For a less dramatic start in metheglin, try a vanilla-cinnamon mead: Add the contents of three vanilla beans and three cinnamon sticks to a 5-gallon (19 L) batch after primary fermentation. Taste the mead after a week, and when you’re satisfied with the infusion, rack the mead into another carboy to separate it from the spices.

ACID AND TANNIN

Honey naturally lacks the acids in most fruit, but to get more of a dry, winelike mouthfeel, some mead makers will add grape tannin and an acid blend. If you’ve found after conditioning that your mead lacks mouthfeel, or seems watery, start with 1/2 teaspoon (2 g) of tannin and/or acid, mixed in water, for a 5-gallon (19 L) batch. If after a few days, that addition does not produce enough character, add more and wait again. Be patient: As with a strong spice, you can ruin a batch by adding these overzealously.

Metheglins only need a spice; any will do.

I would first of all advise someone [who wants to make mead to] understand how to make wine or ale first. Get to know the process, then experiment with different yeasts and honeys.

UNLIKE MOST BREWERS, BOB MAKES HIS BEVERAGE FROM THE SAME RAW MATERIALS HE HELPED CREATE EARLIER IN THE YEAR: HE IS ALSO A BEEKEEPER. OF COURSE, HIS BEES DO A GOOD SHARE OF THE LEGWORK IN CREATING HONEY, BUT BOB’S ATTENTION TO DETAIL AND LIFELONG INFATUATION WITH BEES CREATES AN EXCEPTIONAL MEAD.

HOW DOES ONE CHOOSE TO GET INTO BEEKEEPING?

I started beekeeping as free child labor when I was six years old. My parents literally lined me up with beekeeping equipment and told me to get the colonies ready for next season. Painting, scraping boxes, all the light-duty stuff. From there, I just took an interest in sticking my head into hives and seeing what the bees were up to.

NOVICES MIGHT THINK, “MY GOD, I CAN’T GET NEAR.”

That’s one reaction we get quite often. The other reaction is they want to just jump in without protection. They think of bees as benevolent and friendly, but bees can have bad days as well. You’ve got to get to know the livestock, as it were.

DO BEES HAVE PREDICTABLE TEMPERAMENTS?

Yes, if we’re talking about the standard European honeybee, which we use for most of beekeeping. But it depends on the breed. What we’ve done as beekeepers over the millennia is breed for certain characteristics like survival, honey foraging, and attitude. Beekeepers don’t want to work with bees that want to sting them.

YOU SAID EUROPEAN HONEYBEES, BUT WHAT ABOUT YOUR NATIVE NORTH AMERICAN HONEYBEES?

The European honeybee is a European-Western Asiatic bee. They probably arrived with the early European settlers. There are upwards of 19,000 native species in North America, so they’re not uncommon. Unfortunately, none of those bees produce a large quantity of honey, though a lot of them are good pollinators. When it comes to honey quantities, the European honeybee is on top of the pile.

SO WHAT DO YOU KNOW ABOUT NATIVE NORTH AMERICAN INTERACTIONS WITH OTHER BEES?

There’s a lot to be studied, particularly since we’re moving bees around the planet with regularity now. With them, we transport pests and pathogens, and some bee populations are undoubtedly [more] susceptible. There are proven cases of the bumblebee industry importing bees from China and transferring various nosema diseases into native bee populations and decimating them.

THERE’S BEEN A LOT OF TALK ABOUT HONEYBEE DIE-OFF.

It’s nowhere near being stabilized and is probably going to get worse before it gets better. We know a little more about it than we did when it started around 2005. It’s undoubtedly the result of a lot of factors, largely things like climate change, nutritional stress, pesticides, and breeding.

We’re [studying] further pesticides, which are highly toxic to bees. It’s not being treated seriously by researchers [who are] bringing it to market. Europe has banned some pesticides that [North America] promotes. What’s most disturbing is that we’re not only seeing large losses in our bee populations, but also other natural pollinators, like hummingbirds, bats, moths, and butterflies.

It’s a nonsustainable, spiraling problem: Farmers have to use more pesticides every year to save the year’s crop. Are you going to watch your crop get eaten, or spray more pesticides?

SO IT IGNORES DOMINO EFFECTS DOWN THE ROAD. CAN YOU EXPLAIN NUTRITIONAL DISTRESS?

Bees exploited to pollinate large agricultural sectors are put out into 10,000 hectare (25,000 acre) areas of sunflowers, for example, that have very poor nutrition. The average bee only flies up to six miles (10 km), so essentially they’re getting one type of food their entire life. That bee and their colony is forced into nutritional deficit by having one type of food, and that causes a lot of stress in organisms and the whole colony. It’s like having to live entirely on potatoes.

WALK US THROUGH THE BASICS OF MAKING MEAD, WITH A FOCUS ON MAKING MEAD AT HOME.

I would first of all advise someone [who wants to make mead to] understand how to make wine or ale first. There are some fairly nice meads made in an ale style, a honey and malt mix. Get to know the process, then experiment with different yeasts and honeys. One of the most interesting aspects [of mead] is using different types of honey, like you’d use different types of grapes [in winemaking]. Some honey produces very good mead and some honey produces very poor mead.

YOU MENTION WINE- AND BEER-STYLE MEADS. PLEASE DESCRIBE THE DIFFERENCE.

Wine-style [meads have] higher attenuation and greater acidity, and their yeasts are commonly from the wine industry, derived from root or stem yeast. The ale yeast are derived from grain crops. They’re not always, but [they] generally have a lower tolerance for alcohol. Get an idea for what you want to do, then use the appropriate fermentation techniques, instead of trying to hybridize, like using a champagne yeast with ale techniques.

WHAT’S THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN STORE-BOUGHT HONEY AND HONEY FROM A FARMERS’ MARKET?

If you go buying your honey at [a major discount retailer], you could be buying just a percentage of honey and it might have all sorts of crap in it. Some cheap honey is inexpensive because it’s mixed with cheap imported honey.

When you buy a kilo of honey on the cheap, you get a different result than getting a kilo of honey from a beekeeper down the street and being charged more. It’s like using grapes. You can be the greatest winemaker in the world, but if someone throws a bin of crappy grapes at you, you’re going to produce an inferior product.

DO YOU HAVE ANY ADVICE FOR WHEN TO ADD FRUIT AND SPICE?

It depends if it is fresh or not. It really comes down to experimenting and how much you want in flavor, too. It is very much a personal thing. Because mead making is such an old fermentation process, every society has been messing with it and you find many different ways of producing it.

A friend of mine makes t’ej, the national drink of Ethiopia. They use gesho, a hops- like herb that’s related to cannabis. It smells like a cross between low-grade hops and real bad pot, but they add to the boil.

DOES THIS PLANT BRING BITTERNESS?

Yeah, it’s similar to hopping a beer or mead and has a preservative nature.

CAN YOU DESCRIBE THE FLAVOR PROFILE?

It’s a cross between sweet wine and a sparkling ale. It has a bitter taste leaning towards a flat IPA with a little more alcohol in it, but the finish is still quite sweet.

SPOTLIGHT:

THE HISTORY OF MEAD

Most people who study the historical aspect of fermentation believe It was one of the first—that or palm resin wines. Some of the earliest records are rock wall painting in southern Spain, northern Libya, and Morocco, depicting people mixing honey with water to no doubt make alcohol. The beverage is 13,000 or 14,000 years old. Bob Liptrot asserts, “It certainly predates anything Egyptians were doing or anything from most of Europe.”

Mead probably started as a simple substance of diluted honey in water. Liptrot adds, “Our ancestors in neolithic and paleolithic periods probably found they could source it by getting a few bee stings and running like hell back to the safety of their camp. They let it ferment and probably discovered religion around the same time if they drank enough.”

They basically started with crude mead: honey water with maybe a bit of fruit they managed to forage. When you think about the big picture of mead production, the meads that are produced in a brewing style are largely a function of modern agriculture from the past 5,000 years or so.

The two main historical styles of mead that brewers tend to be interested in are metheglins and melomels. Metheglins are spiced or herbacous types of mead and melomels are fruit- or berry-based meads.