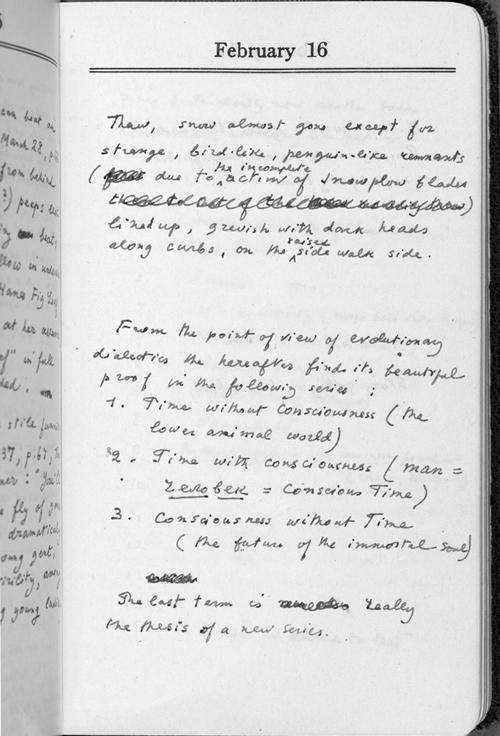

FIGURE 18. Nabokov records thoughts on Time and consciousness.

And when you look over the railing at the bubbly foam rapidly running away, you feel as if you were drifting further and further backwards, standing on the very stern of Tıme.

—Other Shores1

ALL HIS CONSCIOUS LIFE Nabokov was pondering the chief structuring condition of earthly existence, Time. Death, the borderline demarcated by the pale fire of uncreated light beyond which time should be no longer,2 was a mystery whose magnetic chill he felt almost from the “cradle rocking above an abyss.”3 It is possible to consider his drive to write fiction as a sustained attempt at various inquiries into the carefully prepared conditions of time and space. The English term “novel,” a secondhand Italian import, is feckless (as is much of the English generic literary terminology) because it is completely unattached to the drivetrain of the genre, without which, or with an unskilled handling of which, it reliably fails. That drivetrain is Time; that is what sets a “romance,” to use another unfortunate term, apart from other genres of prose fiction.

Proper time handling requires room—and not the other way round: the cardinal difference between a “short story” and a “novel” is not that the latter is a “long story” but that there are specific space demands for re-creating timeflow plausibly. Time in fiction is not mere chronology that ought to be monitored. It is rather a most difficult, deliberate verbal production of the effects of time passing, jumping, bucking, crawling, elapsing, warping, forking, reversing that we experience but can never quite get accustomed to in the course of life. A better term for a “novel” would be something like chronopoeia, a time-craft in writing, compositional time-management, the taming of time.

All Nabokov’s novels are masterfully chronopoetic. He studied in detail, valued highly, and presented to his Cornell students aspects of this very special branch of craftsmanship in Proust, who deftly managed temporal springs and neaps; in Tolstoy, who somehow synchronized his tweaked, thirty-six-hour-a-day chronometer with the mesmerized reader’s standard watch; in Joyce, who broke a score of hours of a single day into twelve-hundred elastic minutes. And, as said before, Nabokov’s own composing of “long fiction” may be viewed as an extended, specialized experiment with Time whose ultimate goal was, if not to grasp then at least to touch the enigma of mortality—a highly pleasurable means to a wittingly unattainable end.

On February 14, 1951, he wrote in his diary:

Space, time, the two prime mysteries. The transformation of nothing into something cannot be conceived by the human mind.

Revisiting the entry on the same date eight years later he added:

The torrent of time—a mere poetical tradition: time does not flow. Time is perfectly still. We feel it as moving only because it is the medium where growth and change take place or where things stop, like stations.

Two days later he drafted a clear-cut supposition that he had tried in less streamlined forms in his earlier writing and that became a founding principle in his last three novels:

Feb. 16.

From the point of view of evolutionary dialectics the hereafter finds its beautiful proof in the following series:

1. Time without consciousness (the lower animal world)

2. Time with consciousness (man = chelovek4 = conscious Time)

3. Consciousness without Time (the future of the immortal soul)

The last term is really the thesis of a new series.5

It can be said, perhaps, that before his “experiment with time” according to Dunne’s prescription, Nabokov’s view of the place of time in art was somewhat simplistic: he proposed that art depended on the “perfect fusion of the past and the present,” but “the inspiration of genius adds a third ingredient: it is the past and the present and the future (your book) that come together in a sudden flash; thus the entire circle of time is perceived, which is another way of saying that time ceases to exist.”6 This position grew much more sophisticated by the 1960s, after the experiment—arguably, as a result of it.

FIGURE 18. Nabokov records thoughts on Time and consciousness.

Rightly heard, all tales are one.

—Cormac McCarthy7

Nabokov’s post-experiment fiction—three published novels and one left unfinished at the time of his death, all written inside and in the vicinity of a Swiss grand hotel in Montreux, where he lived for the last fifteen years of his life—differed from his previous novels in a number of ways. The most significant difference is a new and special handling of the time dimension, that “backbone of consciousness,” as Van Veen puts it, and therefore the backbone of any artistic fiction simulating the human condition. Time-travel became much more extended than before, making up, in a disproportionately staggered form, the entirety of Ada and much of the other two novels’ narrative space.

Time-molding took very complex shapes. Death, as a personal end of time, grew into an overarching theme. In all these novels Nabokov seems to be testing Dunne’s idea that Time is not an inexorable, irreversible Heraclitic river-stream that cannot be entered twice and so on; rather, it is an alternating electric current that pulses in both directions. Change can be changed back.

The cards on which he drafted Ada, the first fiction Nabokov wrote after his dream experiment, shared a big folder with the dream cards. The seven-year gap between that novel and the previous, Pale Fire, was the longest for him,8 and the resulting book turned out to be twice as fat as the previous largest, The Gift. Like that Russian novel, Ada is made up of five parts; unlike it, the parts are of pointedly unequal length. Part 4 is the plot-carrying core: most of its room is taken by Van Veen’s essay entitled The Texture of Tıme. Its postulate is basically apophatic: the notion of Time should not be confused with, or suffused by, that of space: the two must be uncoupled once and for all. Yet within the novel this proposition contains a curious self-biting antinomy: Van is mind-handling this theory while driving at full throttle to meet Ada at Mont Roux, as if ignoring the fact that speed is time mating distance (and he somehow erases a day in the process).9 In a remarkable scene in The Gift, a character lying in bed in a darkened room, pondering death, hears the noise of “trickling and drumming” water behind the tightly blinded window and arrives at the trite conclusion that there is nothing afterward, which, he thinks, is as certain as the fact that it is raining. And yet it is bright and sunny outside, and the tenant upstairs is watering her flowers on the balcony. Could Van’s conviction that time and space must be divorced be similarly mistaken? After all, the morning after that spastic journey through space, in a frantic effort to outrun time, he sees, against all expectations, Ada standing on the balcony one floor below his.

Nabokov, who once let it be understood that he did not share all of Van’s views on time,10 seems to undermine the cardinal point of Van’s theory by correlating temporal dimension with a spatial one. Ada’s five parts are sized in inverse proportion to the time period they span. “Time is rhythm,” pronounces Van;11 but rhythm is the spacing of time. Part 1, composed of 43 chapters, takes up 325 pages in the first edition, well over half of the book’s total bulk, and covers the events of less than four years, 1884 to 1888 (discounting the pluperfects at the beginning necessary to flesh out Van and Ada’s common genealogy); part 2, of only 11 chapters and 120 pages, propels the narration to 1893; part 3 has eight chapters and 93 pages but covers 29 years, 1893 to 1922. The seminal part 4 makes up a single harried chapter and spans, in a matter of 28 brisk pages, the three (or four) days in mid-July 1922. (It is the only part with no interpolations by Ada, who nevertheless has the last word: “We can know the time, we can know a time. We can never know Time. Our senses are simply not meant to perceive it. It is like—” . . . death was probably the inaudible word, or what comes after death.) Van Veen covers considerable space in a relatively short time, all the while trying to cut off Time from “Siamese Space” and to expound on the falsehood of the future—which comes rushing in the last part, only 22 pages long, its hurried six chapters accounting for the rest of the timeline, a tremendous space of 45 years. There is a neat stability in this receding proportion: the size ratio of parts that have one part between them (I–III, II–IV, and III–V) is kept about the same: four to one. In a sense, this inversely progressive de-spacing is akin to the phenomenon of the reverse perspective, a concept that Florensky explored in depth in 1919–24.12

Viewed another way, Nabokov uses about 30,000 words to present one year for the first four years of narration (including the initial flashbacks); about 9,000 words per year for the five following; approximately 1,200 words per year on average for the next 29; and allots only about 400 per year for the remaining 45 years of the storyline, counting parts 4 and 5 together. “Time is but memory in the making,”13 Van states further, and his chronicle drives the point home, so to speak, since the first four years are more richly worded, much more brightly preserved, much better restored, in other words, much more real than the remaining eighty, getting dimmer as Van and Ada asymptotically get older.

His next novel, Transparent Things, is half the size of Ada’s part 1 alone. Its intricate diegetic device removes the bodiless narrators, all of them dead, from terrestrial conditions and places those spirits in the timeless realm from which they unfold the story of Hugh Person. They pronounce utterances in unison, like a tragic chorus; they know in depth the past and in width the present of all men and things, and the future for them is, presumably, the present. This design is so difficult that, seeing that even the sharpest readers did not quite grasp it, Nabokov went so far as to make up an interview in which he explains to the imaginary questioner the book’s real plot-work.14 It is of note that the title is a double-take, of the Finnegans Wake type: the narrating “things” are transparent (invisible) to the living; at the same time, all things are transparent (knowable) to them. Incidentally, since both these aspects cannot be retained in one Russian phrase (because the stricter semantic range of the word “things” drains the phrase of the first meaning), Nabokov privately called this slim but significant book in Russian Skvozniak iz proshlago, a draught from the past, а line from his 1930 poem about a sense of the hereafter, entitled “To the Future Reader.”15 This arrangement is markedly different from the way Dante’s spirits see the time dimension: the past and the future are indeed transparent to them, but they are “denied the sight of present things.”16

Like Van Veen, Vadim Vadimych N., the narrator of the last novel Nabokov published, rather senses than suspects the coexistence of another world, unreachable but permeable, which his much happier and healthier maker inhabits. Is his world an interminable dream? One of Dunne’s important points is that precognitive dreaming is a normal human faculty, which almost nobody registers owing to inattention. VVN is beset by what he thinks is a singular mental handicap, perhaps a sign of encroaching madness: he cannot perform a mental roundabout of spatial progress so that he would see objects just passed in reverse order. As if confirming Van’s insistence on removing Space from the space-time, VVN’s marvelously congenial last wife resolves his lifelong conundrum by explaining that he takes imagined spatial progress for temporal: it is exceedingly hard to reverse Time. Yet memory does not reverse it: it makes the past present.

It’s queer, I seem to remember my future works, although I don’t even know what they will be about.

—The Gift17

Definitions of Time usually exhibit a tendency toward short-circuiting. A character in a mimetic fiction may be allowed to conceive time as rhythm or as memory-in-the-making, but he cannot have license to imagine a world transcendental to his in which his time could be stretched, kneaded, or reversed as need be, that is, in effect a world where, from his standpoint, there is no time. Van Veen might feel at home in the company of the so-called detensers, such as J. M. McTaggart and, to a lesser degree, his younger Cambridge colleague and opponent Bertrand Russell, who tried to divorce Time not only from Space but also from itself, collapsing the dimension to a figure of speech. If Time is an allegory for change, then, they would argue, change is “nothing more than things having different properties at different times.”18

It is not unthinkable, though rather unlikely, that Nabokov saw an interesting 1935 letter to the editor of Philosophy, a quarterly published by Cambridge University, in regard to Dunne’s theory of Time. While conceding that “general indebtedness of thought to Dunne” may be great, Joshua Gregory, a British philosopher of considerable renown, a younger colleague of McTaggart and Russell, arrives at a conclusion very similar to Van Veen’s: “[The] presumed infinite regress of Time is based fallaciously on an illegitimate spatialization,” pointing out a “seeming initial error—an attempt to convert Time into a kind of Space.”19 And yet the measuring rod of astrophysicists is the distance that light covers in a year: an exemplary space-in-time unit.

Modern physical science is so thoroughly alienated from metaphysics, indeed from any sort of idealistic philosophy, that attempts to make sense of the relationship between quantum mechanics and gravitational theory lead to dry absurdities, because, in the shrewd words of a recent interpreter, they “seem to eliminate time as a dimension altogether, leaving us with nothing even recognizable as normal change,”20 thus hopelessly confusing a metaphysical condition with a physical one, without acknowledging the fact. The hypothesis of gravitational waves as an extension of the theory of general relativity proposed by Einstein in 1916 appeared to have found validation exactly a century later, when LIGO detectors situated in Louisiana and Washington both “measured ripples in the fabric of spacetime—gravitational waves.”21 That particular metaphor of rippled fabric is very close to Nabokov’s “folding carpet” of time’s pliable patterning; indeed, he wrote a short story based on the proposition that waves of gravitation may warp space-time (“Time and Ebb,” 1944). In that story undulating Time re-laps and re-lapses upon itself. It is one extended déjà vu in effect, set to illustrate why time “ling’reth in childhood, but in old age fleeteth.”

Nabokov’s well-known insistence on rereading is a cardinal element of his aesthetics. The principle of rereading entails the notion of reverse reading, that is, going from effect to cause, ultimately from the end to the beginning—of a unit (chapter, part) and of the whole (novel). Rereading also entails, ineluctably, a passive imitation of the author’s act of multilayered rewriting of his text. Reading, of course, is nowhere near writing in intensity and sheer compositional ecstasy. There is a quantitative compensation, however: one has reread what the writer wrote many more times than the author did.

Viewed from a different angle, rereading amounts to a spatial reversal of time, a vitally important problem with which Nabokov’s deeper-thinking characters (e.g., Van Veen in Ada and Vadim Vadimych N. in Look at the Harlequins!) grapple so memorably and so futilely. In general, in his Montreux novels, more than in the preceding ones (The Defense is the only exception), subsequent readings reveal new layers of previously stored but missed intelligence, discoverable only by sailing back in time, spar-buoy by spar-buoy. The (re)reader of the second half of such a novel is in a regular flood-and-ebb mode, constantly reaching back to earlier chapters for illuminating theme-tracking.22

A formal model of backtracking time in prose underpins Nabokov’s early English piece with the awkward title “Time and Ebb,” where the first word evokes “tide,” as in Shakespeare’s “the tide of times.”23 Here Time is made, not to warp, as it may in a regular novel, but to boomerang, to fold back onto itself like a tidal wave: Time booming like a tide, ranging like waves. In that story, narrated by a coeval of Nabokov’s son Dmitri, the reality of the present time-space (1944, New York City) falls under study by means of an extraordinary application of the making-strange device. Read superficially, it is a wistful account furnished by an astoundingly detailed, clear vision of a beautiful, heroic, imperfect past, recollected from a point of great remove for the benefit of the memoirist’s younger contemporaries. But on a higher plane, a pencil of rays is projected into the remote future only to be reflected back onto the world of the story-maker rather than teller, and it is in that strange light that the readers of the New Yorker, where the story appeared, were invited to see, as if for the first time, the “brass and glass surfaces” and the “whirr and shimmer of a caged propeller” in the milk bar of a drugstore, or the sunset of a “greenhouse day” in Central Park, with its “old-fashioned . . . lilac-colored . . . aquatic skyscrapers” and “Negro children [sitting] quietly on artificial rocks,” or else they, the first readers, were reintroduced to the rum habit of pushing numerous tiny buttons through tight slots in their garments. Time courses back and forth, looping moebiusly as it were, depending on the terrace we take for observation, even though it somehow turns out to be one and the same in the end. Shortly prior to “Time and Ebb,” Nabokov tried a peculiar “future in the present imperfect” tense at the very end of The Gift, where the hero envisions writing someday the very book that is dwindling in the reader’s hands, and also in The Real Life of Sebastian Knight, whose surface narrative trick is predicated on moving through the timeflow upstream, from the certain fact of the hero’s death to the hazy beginning of his uncertain life reflected in a chronological series of his books. It seems that between 1937 and 1944 Nabokov was trying a complex technique of writing forward whilst narrating backward.

He liked reversals both in word games (he found anagrams and even palindromes irresistible, once writing a perfectly reversible rhymed Russian quatrain into an album of his and Joyce’s friend, Lucie Noël Léon, the palindrome of whose maiden-married name could not have escaped Nabokov’s eye) and in chess (the so-called retrograde analysis, explained in Speak, Memory), and employed both in his writing. The Gift and The Real Life of Sebastian Knight, the last Russian novel and the first English one, composed adjacently, both employ an elaborate device of real narration running backward, against the current of progressive unfolding of information. The reader of either book learns at the end that there is no end: the storyline begins on the last page and takes you back to the level right above the entrance, in a never-ending helicoid rereading process. Indeed, retrograde analysis may be a happy way to describe Nabokov’s axiom of proper reading of a novel. In a chess game, as in life, ground rules forbid taking moves back; but in a retrograde chess problem one is supposed to, indeed must, take moves back, one by one, all the way to the beginning, a solid metaphor for the notion of reading backward, as it were: retracing one’s steps. And, to revise Nabokov’s favorite dictum, if a book is not worth retracing (checking hidden key points by backing up to the beginning) and rereading (now enlightened by the discoveries made by retrogressing), it is not worth reading the first time.

The principal movement in Nabokov’s prose is perhaps that of shuttling, of going back (when memory is at work) and forth (when imagination is engaged), and it is that interaction of memory and imagination that makes true fiction possible and the make-believe powerful, and this is exactly what Nabokov expects the reader to have and to use.24

“The future is but the obsolete in reverse,” we read in “Lance,” Nabokov’s last short story,25 which, unlike “Time and Ebb,” is projected plainly into a fathomable future, predicting in reverse, as it were, and thus reversing the etiology of an event. But strictly speaking “the future is . . .” is a disagreeable linguistic fallacy, whereby a present-tense verb is made to predicate that which is not in the present. The other grammatical means to express it predicatively in English (and in many other languages) are merely ways to sidestep the conundrum by expressing one’s wish or hope or obligation. “Sham Time,” Van calls it (perhaps with a nod to Finnegans Wake) and further elaborates on that sensible abnegation of the future, that “faculty of prevision.”26

Certain passages . . . sound a prophetic, even doubly prophetic forenote not only of the later atomystique but of still later parodies of the theme—quite a record in its small dark way.

—Foreword to The Waltz Invention

Clairvoyance, a term of specifically religious origin and connotation, does not imply foreseeing the future; rather, it stands for seeing the future as if it were present. “Time and Ebb” stages a somewhat gawky experiment that aims to do just that—but in reverse, since only the actual reader, and not the fictive narrator, knows what is projected, whence, and whither.

With Nabokov, the incidence of a phenomenon for which I cannot find a fitter description than a strangely accurate foreglimpse of an event that has not yet happened is disconcertingly large. Once one has exceeded the number of instances that still feels probable and then sees that number doubled and trebled—rather like in the coin-flipping prologue to Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead—one doesn’t quite know what to make of it or what to do with it. It is one of those things that are at once awkward to display and a shame to discard. It is a staggering chance meeting an improbable alternative to chance; their meeting place is aporia.

Those instances range from gratuitous to scientific to mystical. On the silly end of it, Pale Fire’s narrator’s powerful motorcar is called “Kramler,” likely a portmanteau of Chrysler and Daimler-Benz. In 1998 the two automakers merged and their official corporate name became “DaimlerChrysler” (they divorced nine years later). In the same novel, Nabokov coins “modem,” another happy portmanteau whose currency, since its invention in 1958 until much later, was limited to the US air defense’s shorthand for “modulator-demodulator.” Nabokov’s modems stand for “modern democrats,” a funny foresight in hindsight. (This somehow reminds one of Shakespeare’s making Hermione exclaim, with restrained pride, “The Emperor of Russia was my father”—more than a century before the first such emperor, Peter I, was proclaimed.)

“I often think,” Nabokov once said, that “there should exist a special typographical sign for a smile—some sort of concave mark, a supine round bracket . . .”27 Now, of course, this ubiquitous smiling roundface grins at you from every screen as a preemptive sign of nonaggression.

Much as he predicted, the late twentieth- and early twenty-first-century “denominations of time” might indeed look to the anglophone people of the earlier twentieth century like “telephone numbers” (“Time and Ebb,” 581), as digital clocks in the 1980s supplanted the descriptive half-past-fours in favor of the often excessively precise four-thirty-ones (or even the military-style “sixteen-thirty-one”), then briefly gave room to “analogue” watches while retaining the hyperaccurate time-telling of the digital ones, then yielded the entire what-time-is-it business to electronic devices and, most recently, to computers imitating wrist watches. And while in Antiterra’s de-electrified, hydraulic-powered world the “dorophone” (a fantastic telephone stand-in), smart as it may be, does not resemble an iPhone, “the new instantogram” certainly predates the Instagram by half a century.28

Here is a more complex case, but just as absurd and as annoyingly “wondrous strange” (to quote Horatio). Following chess moves and names in The Real Life of Sebastian Knight takes one on a fascinating journey to a dead end. Even before the book was published, Nabokov told Wilson, who had read it in manuscript and wrote a curious blurb, that “. . . no—except for the sketchy chess-game alluded to in one chapter there is no ‘chess-idea’ in the development of the whole book. Sounds attractive, but it is not there.”29 A small town called Roquebrune is where Sebastian’s mother died. He visits the place, senses her ghostly presence in the pension’s garden, only to discover later that she had spent her last months in a different Roquebrune (in the Var rather than Cap-Martin). It seems quite likely that Nabokov chose that particular place because of its faintly chess-sounding name (roquer means to castle, i.e., to have a rook leapfrog the king). In 1992, seventy years after Sebastian had sat on that garden bench at Les Violettes, a Dutch tycoon named Joop van Oosterom staged in that very town the first of the twenty annual chess tournaments called “Melody Amber” (after his newly born daughter), with specially invited elite players. That first tournament in Roquebrune, incidentally, was won by a Ukrainian named Ivanchuck.

Here is another curious case of strikingly limpid guesswork verging on augury. Pnin’s former wife, Liza Wind, visits him in the piercingly sad second chapter and says:

“I think I’ll lie on your virgin bed, Timofey. And I’ll recite you some verses. . . . Listen to my latest poem,” she said, her hands now along her sides as she lay perfectly straight on her back, and she sang out rhythmically, in long-drawn, deep-voiced tones . . .

Forty-five years after this was written, Emma Gershtein, a friend of Anna Akhmatova—Liza’s paragon in poetry and pose—published her rather scandalous memoir in which one finds this description of an episode in 1941: “Anna Andreevna [Akhmatova’s patronymic] lies in her bed almost all the time, and without even lifting her head from the pillow is reciting for me, muttering as if in trance [почти бормочет], her new poem.”30

In the short story “Double Talk,” an atypically topical and therefore somewhat awkwardly stitched together 1945 short story (later renamed “Conversation Piece, 1945”), the narrator encounters a seedy Russian émigré colonel at an implausibly disgusting soirée of German sympathizers. The man is of the kind that Nabokov found particularly repulsive: a “Red Monarchist” and a Soviet end-of-war patriot. The narrator doesn’t quite catch his name at introduction: “. . . a Colonel Malikov or Melnikov . . .” Six decades on, a number of display features of the Russian Federation’s ideological tenets fit uncannily, almost verbatim, the good colonel’s ideals (“The great Russian people has waked up and my country is again a great country. We had three great leaders. We had Ivan, whom his enemies called Terrible, then we had Peter the Great, and now we have Joseph Stalin. . . . Today, in every word that comes out of Russia, I feel the power, I feel the splendor . . .”). Moreover, two prominent trans-Soviet Nabokov critics happen to be called Malikova and Melnikov.

In the fast-moving, toponymical part of Lolita, drafted mostly while he himself was traveling across America, Nabokov lists the places where Humbert and Lolita “had rows, minor and major. The biggest ones we had took place: at Lacework Cabins, Virginia; on Park Avenue, Little Rock, near a school . . .” and several more. The Nabokovs passed Little Rock already on their first long-distance motoring in 1941 and might have done it again on a subsequent trip west and southwest.31 At the beginning of the 1957 school year, that is, at least four years after Lolita was finished, nine black students enrolled in the racially segregated Central High School in Little Rock, which caused a crisis that required President Eisenhower’s intervention. Central High is on Park Street. One block down is S. Schiller Street (Lolita was to become Mrs. Schiller).32

Among the more absurd osculations of this sort stands out an episode that Nabokov describes in rich detail in one of his interviews, unsuspecting of the punch line. In February 1937, in Paris, he was asked to give a reading on Pushkin as a last-minute substitute for Yolanda Földes, the Hungarian authoress of La Rue du chat qui pêche, a pretty ghastly best-selling novel inhabited by faux-Russian farcical characters with names straight from a Hollywood script-book (“‘She loves Fedor, not Vassja,’ Tuchachevski said to Bardichinov”). As Nabokov entered the Salle Chopin, the Hungarian consul raced to him to express his sympathy, mistaking him for the husband of the suddenly indisposed lady-writer.33 The husband’s name—the name that the good consul had on his lips as he extended his hand to the surprised lecturer—was “M. Clarent,” a French homophone of the name of the cemetery where Nabokov was to be buried forty years later.

Nabokov rejected, for serious philosophical reasons, generic science fiction but himself was not alien to the fiction of foreknowledge, in areas as diverse as geopolitics, psychology, cosmology, and of course his specialized branch of biology. One of Brian Boyd’s articles aims to show that Nabokov anticipated certain important recent discoveries about human nature.34 In “Lance,” a fantasy written ten years before the earth could be seen from outer space and a full seventeen years before photographic images of its entire lapis-lazuli globe as it was rising over the moon’s horizon were published in Stewart Brand’s techno-hippy Whole Earth Catalog, Nabokov imagined what it would look like if viewed from another planet:

My young descendant on his first night out, in the imagined silence of an unimaginable world, would have to view the surface features of our globe through the depth of its atmosphere; this would mean dust, scattered reflections, haze, and all kinds of optical pitfalls, so that continents, if they appeared at all through the varying clouds, would slip by in queer disguises, with inexplicable gleams of color and unrecognizable outlines.35

Nowadays young descendants look without any excitement at these images, some of which resemble Nabokov’s description with astounding accuracy.

A few years ago a shocked scientist published a report in which a DNA analysis proved not only that Nabokov was right in theorizing, at about the time of writing “Time and Ebb,”36 that certain Blues (butterflies) had come to the New World from Asia but that they came in five distinct waves. “He got every one [of the stages of migration] right,” said Dr. Naomi Pierce, curator of lepidoptera at Harvard. “I couldn’t get over it—I was blown away,” she told the New York Tımes.37 Moreover, the specific route via the Bering Strait that Nabokov proposed and that seemed improbable at the time (because of the low temperatures) has also received strong support. In Conclusive Evidence, he pursues mentally his first butterfly, a captured but escaped Swallowtail, on its forty-year-long flight from Vyra to Vologda to Viatka to Verkhne-Kolymsk (where it lost a tail over the conglomerate of Soviet extermination camps), and from there, across the Bering Strait (how else?), to Alaska, to be at long last recaptured in Colorado.

In a poem composed shortly before “Time and Ebb,” Nabokov says that he wants above all to be remembered as a discoverer and describer of a butterfly. But his reputation in the world of biology has now reached much farther, into the elite company of those visionaries who worked at restoration of an unfathomable past, and their vision, though shrugged off as wild by their contemporaries, was pronounced right by a posterity they did not live long enough to catch a glimpse of.

There are several recorded instances of what Nabokov called inklings of his posthumous fame, some light and droll, others strangely factual, all baffling. “I open a newspaper of 2063 and in some article on the books page I find: ‘Nobody reads Nabokov or Fulmerford today.’ Awful question: Who is this unfortunate Fulmerford?”38 (This well-known twinkling reply to a silly question has spawned, in half the time predicted, a Fulmerford Club and a webpage that opens on “Yes, I am that Fulmerford.”) This was a simple projection—a clean 100-year throw from the date of that Playboy interview. But here is an earlier and queerer case of a projection reflected. In a 1941 letter to his wife, he whimsically visualizes himself in his present situation from a great temporal distance, much as the narrator of “Time and Ebb” does: “. . . shall I write one little piece in Russian—and then translate it? ‘While living at Wellesley, amidst oaken groves and sunsets of serene New England, he dreamt of trading his American fountain pen for his own incomparable Russian implement’ (From Vladimir Sirin and His Tıme, Moscow, 2074).”39 Why that particular year? What was the mnemonic peg here? His 175th anniversary? Why not just pick the round bicentenary? In any event, that “and his time” viewed from an untouchable remoteness falls neatly into the theme.

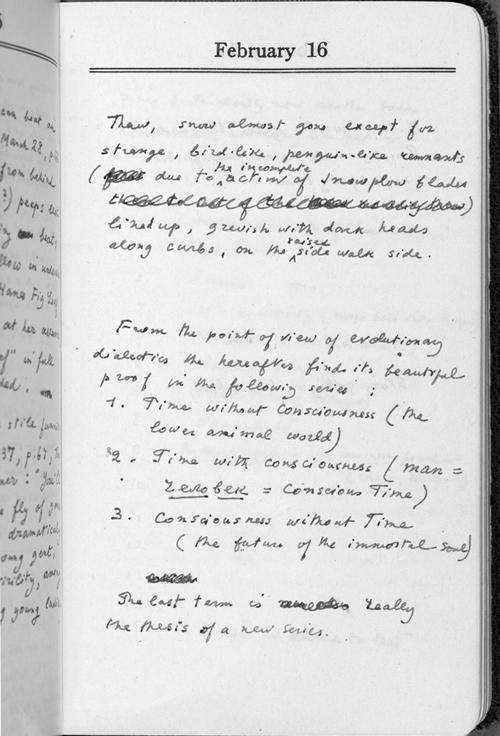

FIGURE 19. An inchoate chess problem, possibly a mate in three, on the verso of the dream card dated November 24, 1964.

Earlier in this book I dwell on two of Nabokov’s prescient dreams, one extraordinarily prodigious, both wondrously Dunnesque.40 But how would Dunne explain the story of Roman Grynberg’s sending Nabokov, in 1957, the first volume of the Lexicon of Pushkin’s Language, just published in Moscow, in response to which Nabokov wrote back from Ithaca in May of that year: “Dear Roman, thank you for the present and the inscription. You will send me the second volume in 1960, and the last one—in 1977.” It was probably nothing but levity: it would take, he implied, the Soviets “forever” to complete the project (in the event, the last volume came out in 1961). However, Nabokov’s projected 1977 would be carved in granite on his gravestone twenty years later.41

In July 1975 he stumbled and fell (“shot down 150 feet,” as he put it in his diary) in the mountains near Davos, almost literally with “a heavenly butterfly in his net, on the top of a wild mountain,” to quote from a shiveringly prescient short poem about one plausible setting of his death scene he had composed three years before that fall. It was a recast of Gumilev’s famous “You and I,” with these lines: “And I shan’t die in my bed, a doctor and a notary at my side, but in some remote mountainous crevice choked by wild ivy.” In Nabokov’s case, the net leapt out of his hand and got caught up in a tree branch, “like Ovid’s lyre,” and could not be retrieved. Nabokov himself was, eventually; he died in a hospital bed after all, from an apparently unrelated cause. Brian Boyd sees in this episode “Hugh Person stuff,”42 but Nabokov—supine, upside-down, unable to get up, a cable car quietly floating over him like a spaceship full of gay, waving aliens—might also recall a place from his last novel, just then published, which has a remarkable foreshadowing of an ethereal journey for which this fall could have been a departure point:

Imagine me, an old gentleman, a distinguished author, gliding rapidly on my back, in the wake of my outstretched dead feet, first through that gap in the granite, then over a pinewood, then along misty water meadows, and then simply between marges of mist, on and on, imagine that sight!43

Not all of the “Time and Ebb” narrator’s recollecting foresights, or, conversely, prognostic remembrances, have come true. The “true nature” of electricity was not discovered “by chance” in the 1970s; the “great flying machines” are still flying, but library index cards have been replaced by intangible catalogs; the great “South American War” has been so far avoided; we still “squeeze . . . buttons into as many buttonholes” and have our “meals at large tables” in a “sitting position,” or at least some of us do; and Russia and France not only do not have a common border (a misogermanic Russian’s dream) but are now separated also by the Ukraine and the Russian Federation.

In the summer of 1926, a year after their marriage, Véra Nabokov, who was unwell, spent two months at a Schwartzwald resort; Nabokov would write her from Berlin a long letter every night, often with attached self-made word riddles and cryptograms. She wrote back much less often, which led to repeated jocular complaint. In one of his letters he remonstrates that “if we published a little book—a collection of your letters and mine—it would contain no more than 20% of your labours, my love. . . . I suggest that you close the gap—there is still time . . .” The time left was fifty-one years to the day: that letter was written on July 2, the date Nabokov was to die. When the collection was published, the “little book” turned out to be an eight-hundred-page three-pounder, in which Véra Nabokov’s contribution amounted to zero percent (because she had suppressed and likely destroyed her part of the correspondence). Curiously enough, Pale Fire was begun on July 2, 1959, and it is on that day that Gradus is chosen to carry out the regicide. In his copious commentaries to Eugene Onegin, Nabokov mentions (as does his creature Pnin in the third chapter of the novel) Pushkin’s obsessive memento mori, in particular his attempts to preview the “fatidic date” by writing down and then closely examining the digits of various plausibly looking candidate years. Here we seem to see a reversal of sorts: inadvertently assigning mnemonic value to a date that would turn out to be the second date on one’s tombstone.

A randomly chosen date for use in fiction; a casually mentioned year in a letter to a friend; a slip of the tongue in a dream on the second day of his experiment; an amusing quid pro quo in a Paris lecture hall—scattered incidentals, trifles if taken singly, yet oddly significant in combination, for they pointed to the time of Nabokov’s death and the places of his cremation and burial. He would have admired this design employed in every one of his novels, had he noticed it—that is, had he not been part of it.

Nabokov’s looping projections into the future had a secret, if deniable, plane. It is as if he were setting up catastrophic situations in fiction in order to render harmless that very possibility in life. The belief that life resists predictability is nothing new, of course, but essaying it in one’s art, so as to preempt an untoward turn in life, is not common. Here again, Nabokov certainly knew the precedent of Pushkin, two of whose 1829 poems had to do with this sort of inoculative divination: “Whether I roam . . . ,” with its memorable lines “. . . Where am I destined to expire—in combat, travels, or in waves?”44 and “Traveller’s Complaints” (1829)—a long list of more or less improbable manners of death on the road (e.g., by being whacked on the head by a swing-beam a clumsy operator might drop at a crossroads).

His prophylactic explorations of more plausible disasters had much more to do with his wife and son than with himself. In a sequel to The Gift, Godunov-Cherdyntsev’s wife dies in a car accident; the differently widowed Sineusov, in the unfinished novel Solus Rex, madly wants to believe that his dead wife’s spirit may be able to communicate; his desperate idea is to try to reverse time and effect a restoration in an imaginary setting of a novel, but even in fiction within fiction she meets with a violent end all the same.45 The theme of some terrible danger threatening a son or a daughter—invariably only one and often of an age close to Nabokov’s only son Dmitri at the time of writing—runs through his early novels and stories written in America. David Krug (Bend Sinister) is tortured to death by the brutal socialist-collectivist tyranny; Dolores Haze (Lolita) is kidnapped by a talented monomaniac; Lancelot Bok (“Lance”) is about to leave behind, for the second and apparently last time, his elderly, stoically adoring parents, to explore the perilous depths of space. In Pnin, his only noncatastrophic (in the classical sense of the term) novel, the richly gifted Victor Wind is lucky to be spared the harm that his addle-headed, Freud-befuddled parents were to inflict on him, just as his “real” father Pnin narrowly escapes the snares of his uncharitable narrator. In 1942 Nabokov wrote a little projection poem of the forfending-by-forestalling type, published only once and never collected:

When he was small, when he would fall,

on sand or carpet he would lie

quite flat and still until he knew

what he would do: get up or cry.

After the battle, flat and still

upon a hillside now he lies—

but there is nothing to decide,

for he can neither cry nor rise.46

And in the shortest and saddest of his English short stories, the postwar “Signs and Symbols,” Nabokov makes the nameless elderly couple dread that their only son, a teenager beset by an apparently congenital mental illness very much akin to autism, might have succeeded after several thwarted suicide attempts. The ending of that story is open like a trapdoor, inviting equally to enter and to avoid. Before the end, the mother is going through old pictures in the family album: “Four years old, in a park: moodily, shyly, with puckered forehead, looking away from an eager squirrel as he would from any stranger.” The park, we learn, was in Leipzig where the family lived at the time. In June 1936 Nabokov’s wife and son spent a month in Leipzig, and in one of his letters to her from Berlin, he responded to something in her previous: “Strange he’s afraid of squirrels.”47 Without the later short story this would perhaps be unremarkable. But it is even more striking for the fact that this passage could be based on Véra Nabokov’s sketches of Dmitri’s childhood that Nabokov had urged her to write and on which chapter 15 of his memoirs (about their son) relies:

Once, I remember, he was desperately frightened. It was on his first trip (to Leipzig) and his first walk in the city park dedicated to the preservation of wildlife—as much of it as there could be preserved in a fairly large city. Pigeons, common and huge ringdoves (were they ringdoves?), squirrels, ducks, all of them so tame that they walked around your feet in circles waiting for crumbs, and innumerable small birds, grown so cheeky that they constantly try to peck at your sandwich between the lunch basket and your mouth. And an occasional rabbit or two playing in the middle of some vast lawn (not quite so tame—they would scurry for cover when you came nearer). This sudden exposure to nature had an unexpected result. A baby who loved to run around (and a fast runner he was) suddenly became a little lap-baby. He refused to take a step. He refused to be carried by familiar and friendly people (aunt, uncle), but clung to me in despair yelling when I tried to put him down for a minute (a big baby, a heavy armful of a baby).48

The real writer should ignore all readers but one, that of the future, who in his turn is merely the author reflected in time.

—The Gift49

Any fiction must harness time and reproduce its progress. At higher levels this illusion is made to resemble time-elapsing by techniques similar to cinematic montage: synchronization, juxtaposition, jump-cutting, etc. Nabokov perfected the art of time management in a novel by flipping the hourglass, as it were, so that events which had not yet happened could be checked against those that had, reversing the chain of causality.

The butterfly chapter in Conclusive Evidence ends on a singular pronouncement without an elaboration: “I confess I do not believe in time.” The Russian version, which is generally smoother, softer-lit, and sadder, is less terse and more lyrical in this instance as well: “I confess I do not believe in transient time [mimoletnost’ vremeni]—a light, gliding, Persian time!” That last attribute, Persian, makes for a smooth transition to his favorite carpet-folding metaphor for Time folding onto itself, making the past present. Yet, in a sense, the dry English statement suffices, for not believing in time is tantamount to not accepting degradation of such nonperishables as love, soul, and mimetic art. If the clarifying synonym of time is change, then “transient time” is a redundancy.

The last chapter of that memoir opens on a homophonic twisting of Horace’s line: “They are passing, posthaste, posthaste, the gliding years.” Horace was calling out, plaintively, repeatedly, his friend’s name: “Postume, Postume”; Nabokov, in the very next sentence, makes clear that not only this last chapter but the entire book is done in the same vocative case—is addressed to “you,” to his friend and wife. Time that seemed to stand still now is slipping by in midstream, rushing toward the end of a book whose secret purpose was to dam timeflow and make it go back. That name, Postumus, which initially meant “born late,” went on to mean “posthumous.”

Nabokov’s grave in the Swiss Clarens has the plain écrivain under his name and next to the dates that stake off the distance of time between the “two abysses,” prenatal and postmortal. The plain restraint of that single word shorn of modifiers is designed to carry the weight of significance. But no matter the significance, it only scratches the surface (which is the literal meaning of the word “writer” in Germanic, Romance, and Hellenic languages) of what the wordsmith really does. Like no other verbal artist before him, Nabokov shaped his observations, sensations, suppositions, and conclusions in supremely exquisite compositions, all the time experiencing, and experimenting with, that “draught from the past.” Toward the end of his life he lets out a sigh in an unpublished Russian poem: if only he were given a dozen more years to live (“prozhit’ eshcho khot’ desiat’ let”), to sense a “draught from Paradise” (“skvozbiak iz raia”).50 It was as if Nabokov felt an invisible presence of a time vortex, where the warm wind of the past meets the much lighter and cooler current of the foretold but unpredictable future, blowing “between remembrances and hope—that memory of things to come.”51 In an earlier Russian poem about the wind from the past the poet foresees his future reader feeling that same wind touching his forehead. Meteorologists call it a reversal wind, vent de retour. In a later English poem about the rain “travelling into the past,” the poet, looking rearward, hopes against hope that the ever-shining beginning of life is secure from later inclemencies:

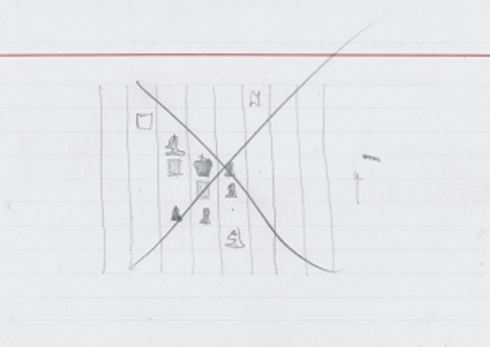

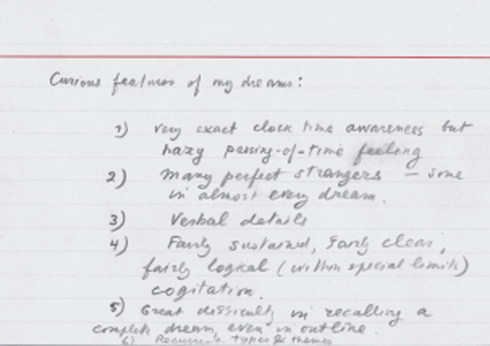

FIGURE 20. This card, “Curious features of my dreams,” appears among the dream records of November 1964.

How mobile is the bed on these

nights of gesticulating trees

when the rain clatters fast,

the tin-toy rain with dapper hoof

trotting upon an endless roof,

travelling into the past.

Upon old roads the steeds of rain

slip and slow down and speed again

through many a tangled year;

but they can never reach the last

dip at the bottom of the past

because the sun is there.52

There is yet another important Russian sentence absent in Speak, Memory. The last passage of chapter 6 begins: “I have wandered far—yet my past is still by my side, and a particle of the future is also with me.”

Speaking of particles: in 2011 the Hadron Collider, the world’s largest subatomic particle accelerator situated on the opposite shore of the lake where Nabokov composed Transparent Things some forty years earlier, beamed a jet of neutrinos, those ghostliest of particles that penetrate any material density, from point A in Geneva to point B in Gran Sasso in Italy, some 684 versts away (which happens to be the perfectly exact distance between the Moscow Fair Square and the Senate Square in St. Petersburg). Much to the bewilderment of the scientists, it exceeded the speed of light, outstripping it by an astonishing sixty feet.53 The speed of light limit is the bedrock of Einstein’s theory: all modern physics and, by extension, much of modern philosophy depend on it, including the origin of the universe and its conjurable age. At speed exceeding that of light, an object so traveling is, according to one bemused physicist, “lighter than nothing, has negative width, and time goes backwards.”54

Lurking among the draft notes for “A Detail of the Ornament,” a technical tour-de-force short story Nabokov published as “The Circle” (1934), there is a neatly compact sentence, unrelated to the story, which offers a surprising and original, if indirect, explanation of why he wrote fiction and even why he wrote it the way he did:

How can I not cosset, cherish, adorn my earthly life, which in the Kingdom to come will serve me as an enchanting amusement, a precious toy for my immortal soul.55

Cossetting, cherishing, and adorning life in an imaginary reconstruction of its givenness accessible (1) to the senses, (2) to psychological empathy, and (3) to metaphysical intuition was Nabokov’s lifelong artistic self-assignment. His incessant efforts aimed to probe, by artistic means, the riddle of human existence between the oblivion of what he calls the “infinite foretime” in Pale Fire and that toward which one is heading. That quest led him to peer into the mystery of death and afterlife, and so it is natural that Nabokov’s fiction can be viewed as a string of exploratory tests of various possibilities, from an almost Orthodox tenet formulated by Dandilio in The Tragedy of Mr. Morn (1924, the year of Van’s essay on Time), to the extraordinary attempt at self-erasure in what is left of his last, unfinished novel.

When, in 1944, Nabokov made the nonagenarian narrator of “Time and Ebb” write, circa 2020, that he “can discern the features of every month in 1944 and 1945 but seasons are utterly blurred when I pick out 1997 or 2012,” he seems to describe nothing more than the well-known foreshortening of an aging memory. He could not, of course, foresee that his son, who was of the same age as the story’s narrator, would die in 2012 on reaching precisely the terminal age of his father. And yet, in the peculiar system of Nabokov’s late-life beliefs, from these seemingly arbitrary coincidences a gentle fogwind blows coming from the unknowable, forever arrested present tense of the story’s author, in the reversible perspective of space without dimension, and time without duration.

1. My translation.

2. Rev. 10:6.

3. From the opening sentence of Nabokov’s memoirs.

4. Russian for “man.”

5. Berg Collection, Manuscript Box: “Diaries, 1951–1959.”

6. Lectures, 378.

7. The Crossing, 406.

8. Eight years separate the publication of Bend Sinister and Lolita, but there was a book of memoir, a nonfiction novel, right in between.

9. See Dieter Zimmer’s most useful “Ada’s Timeline” at dezimmer.net. Van drives flat-out, but he twice takes the wrong turn, has to make up time—and one day gets skipped.

10. Strong Opinions, 143.

11. Ada, 537.

12. See Florensky-1999, 46–103, and Florensky-2000, 190–258. The term “umgekehrte Perspektive” as related to artwork was suggested by Oskar Wulff in a 1907 essay.

13. Ada, 559.

14. Collected in Strong Opinions, which apparently contains two more auto-interviews.

15. Related to the author by Nabokov’s widow in a private conversation.

16. “It seems, if I hear right, that you can see

beforehand that which time is carrying,

but you’re denied the sight of present things.”

“We see, even as men who are farsighted,

those things,” he said, “that are remote from us;

the Highest Lord allots us that much light.

But when events draw near or are, our minds

are useless; were we not informed by others,

we should know nothing of your human state.

So you can understand how our awareness

will die completely at the moment when

the portal of the future has been shut.”

—Inferno 10: 97–108 (trans. Allen Mandelbaum)

17. First imaginary dialogue.

18. See David Papineau, “Tensers” (review of Lee Smolin’s Tıme Reborn), TLS (Sept. 13, 2013), 23.

19. Philosophy (Cambridge University Press, the Royal Institute of Philosophy) 10, no. 39 (July 1935), 380.

20. Papineau, op. cit., 23.

21. LIGO = Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory. Reported in B. P. Abbott et al., “Observation of Gravitational Waves from a Binary Black Hole Merger,” Physical Review Letters 116, no. 6 (2016).

22. In a curious recent case of a “chronic déjà vu” (an interesting choice of adjective), a British man fell into a “constant loop of time”: see Emma Ailes, “Terrifying Time Loop: The Man Trapped in Constant Déjà Vu,” BBC News, January 24, 2015, www.bbc.com/news/uk-30927102.

23. Julius Caesar (3.1.272). Actually, “tide and ebb” would be technically an incorrect antonymy.

24. The effects of a reverse timeflow can be particularly striking in cinematography, but they are seldom employed to any depth, let alone sophistication. Nabokov might have seen the crude Escape from the Planet of the Apes (D. Taylor, 1971), but he would likely find the brilliant shifting of time frames in the television show Lost (J. J. Abrams et al., 2004–2010) fascinating.

25. Stories, 635.

26. Ada, 548, 560.

27. Strong Opinions, 133–34.

28. Ada, 552.

29. Nabokov–Wilson Letters, 51.

30. Emma Gershtein, Memuary, 264.

31. See Robert Roper, Nabokov in America, 51.

32. The “coincidence” spotted by Jeremiah L. Monk, then a Wesleyan University student.

33. See Strong Opinions, 86; Boyd-1991, 434.

34. “Nabokov as Psychologist,” in Brian Boyd, Stalking Nabokov, 109–22.

35. Stories, 639.

36. See his published and unpublished papers and notes of 1943–44, collected in Nabokov’s Butterflies.

37. Carl Zimmer, “Nonfiction: Nabokov Theory on Butterfly Evolution Is Vindicated,” New York Tımes, January 11, 2011.

38. Strong Opinions, 34.

39. Cf. Letters to Véra, 444.

40. See pp. 22–23.

41. R. Iangirov, ed., Diaspora: Novye materialy (Paris, St. Petersburg: Athenaeum-Phoenix, 2001), 522.

42. Reference to an episode in Transparent Things, Nabokov’s next-to-last novel. See Boyd-1991, 652.

43. Look at the Harlequins!, 240.

44. Nabokov quotes these verses in Pnin (ch. 3) and in the short story “Cloud, Castle, Lake” (1937).

45. See Nabokov’s preface to the English version: Stories, 680.

46. Atlantic Monthly, January 1943, 116.

47. Stories, 600–601. Letters to Véra, 274.

48. “Véra Nabokov on Dmitri’s Childhood,” undated, autographed typescript (6 pp.), Manuscript Box: “Nabokov, Vladimir Vl., Biographical and Genealogical Notes,” Vladimir Nabokov Archive, Berg Collection, New York Public Library. I am grateful to Professor Olga Voronina for pointing out this source.

49. Second imaginary dialogue.

50. Written on an index card, in a folder now in a private archive in Palm Beach, Florida.

51. From “Dom” (Home), a 1919 poem by Khodasevich that Nabokov certainly knew: «между воспоминаньемъ и надеждой, / сей памятью о будущемъ».

52. “Rain,” in Poems (1959).

53. A retest done by a different team, reported on March 15, 2012, did not confirm the initial finding (see arXiv.org/abs.1203.3433) but, in a sort of accelerated Popperian cycle, immediately generated calls for a re-retest.

54. See Michio Kaku’s report in the Wall Street Journal, September 26, 2011. Much of this was proposed in detail about ninety years earlier by Florensky in his book Mnimosti v geometrii [Imaginary Values in Geometry] (Moscow: Pomorie, 1922) and developed by Alexey Losev.

55. “Какъ мнҌ не нҌжить, не пҌстовать, не украшать моей земной жизни которая въ царствҌ будущаго вҌка будетъ служить прелестной забавой, дорогою игрушкой для моей безсмертной души.” The Berg Collection, New York Public Library. Folder in Manuscript Box: Detal’ ornamenta.