The impression that visitors receive of Seattle today – a self-confident, prosperous, and eminently livable city – belies the eccentricity and gritty character that mark its earlier history.

First inhabitants

The Puget Sound area, with its mild climate, abundant with fish, wildlife, and crops, was inhabited by peaceful tribes like the Salish and Duwamish. Fishing and hunting only their own lands, with seashells for currency, they bought dressed deer and elk skins from easterly inland tribes.

The first Europeans to see this area landed under the command of an Englishman, Captain George Vancouver, near what is now Everett, north of Seattle, in 1792. The Hudson’s Bay Company was based to the south in Fort Vancouver on the Columbia River, along the present-day border between Washington and Oregon. A ragtag group of social outcasts was engaged to bring in the pelts of sea otters and beavers and deal with the indigenous peoples. For three decades, the distant landlords of the Hudson’s Bay Company dominated the Northwest, but the mid-19th century gold strike in northern California and the opening of new trails to the West pushed out the corporate bureaucrats and fur traders.

Dressed in a breechcloth and faded blue blanket, the 6ft (1.8-meter) -tall Chief Sealth, with steel-gray hair hanging to his shoulders, caused quite a stir among the early settlers of Seattle.

Pristine regions of the Pacific Coast were carved up by zealous city builders and entrepreneurs, and there were already a handful of settlers in Puget Sound when David Denny and his party reached the sandy spit of Alki Point – south of present-day downtown Seattle – in September 1851, which they named Alki-New York (alki means ‘by-and-by’ in Chinook, and New York was Denny’s home town).

Chief Sealth, for whom the city is named.

Historical Society of Seattle and King County/Museum of History and Industry

Flattery and fraud

A dismal winter revealed that Alki-New York was an unsuitable site for a cabin, let alone a city. Denny realized that a deep-water harbor would be needed, so he borrowed a clothesline, tied horseshoes to it, and took a dugout canoe along the coastline, plumbing the depths until he found deep water in Elliott Bay. The site for present-day Seattle had been chosen.

Denny, Carson Boren, and William Bell staked out claims on the waterfront and were soon joined by Dr David Swinson Maynard. Medical doctor, merchant, lumberman, blacksmith, entrepreneur, and all-around visionary, Maynard – like thousands of pioneer settlers – had come by the Oregon Trail, a 2,000-mile (3,200km) trek, fraught with dangers of death and disease, from the Mississippi River through the Rocky Mountains to the mouth of the Columbia River.

The first store

Maynard hired local tribesmen to build near the Sag, as they called the land by the water, and within a few days his new store was selling ‘a general assortment of dry goods, groceries, hardware, etc., suitable for the wants of immigrants just arriving.’

In Olympia, Maynard had befriended a local tyee (chief) named Sealth (pronounced see-alth and sometimes see-attle), leader of the tribe at the mouth of the Duwamish River, where it entered Elliott Bay. Europeans in the region considered him among the most important tyee in the territory, and Maynard’s suggestion to name the new city Seattle – in honor of his noble friend – became reality, replacing the native name Duwamps.

Early Pioneers

City building was a booming enterprise in 19th-century America. A determined developer laid claim to a location with promise, devised a town plan, then enticed settlers and investors, using any means at his disposal – from bribery and exaggeration to flattery and fraud. Thus began the towns of Steilacoom, Olympia, Whatcom, Port Townsend, Tacoma and, most successfully, Seattle. Men heavily outnumbered women to start with, and prostitution became part of the landscape. Eventually more women were brought to the area to boost morale and become future brides, but it must have taken a hardy spirit to accept the less-than-genteel conditions in those early days.

Maynard employed Native Americans to cut a stand of fir behind the store into shakes, square logs, and cordwood, while others caught salmon and made rough barrels. When the ship Franklin Adams docked in October, the entrepreneur had 1,000 barrels of brined salmon, 30 cords of wood, 12,000ft (3,700 meters) of squared timbers, 8,000ft (2,400 meters) of piling, and 10,000 shingles ready for shipping.

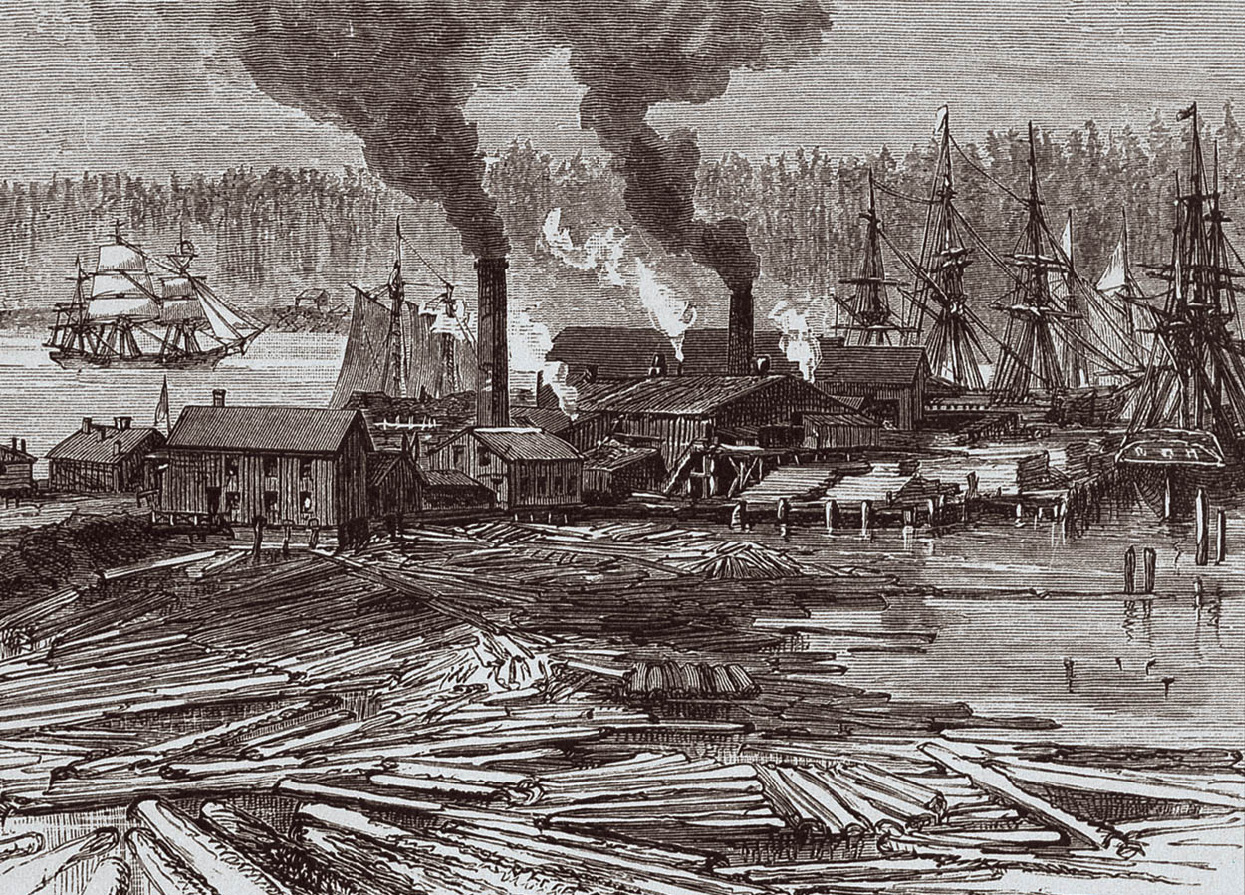

The salmon spoiled, which ruined most of his profits, but ‘Doc’ Maynard’s enthusiasm wasn’t dimmed. What was good for Seattle was good for Maynard, so when Henry Yesler arrived scouting the Sound to locate a steam-driven sawmill, Maynard and Boren both contributed land at the water frontage.

Sawmills dominated the streets of early Seattle.

Bruce Bernstein Collection/Courtesy of the Princeton University Library

Sawmills and strained relations

The rugged residents built a log cookhouse and started on ‘Skid Road,’ a log slide for the timber to slip down the hill to the sawmill. When Yesler returned from San Francisco and set up his equipment, Seattle took a large step forward. ‘Huzza for Seattle!’ said the paper in Olympia. ‘The mill will prove as good as a gold mine to Mr Yesler, besides tending greatly to improve the fine town site of Seattle and the fertile country around it, by attracting thither the farmer, the laborer, and the capitalist. On with improvement!’

Seattle became the government seat for King County, and Doc Maynard’s little store became the site not only of the post office but even the Seattle Exchange.

Though the local tribes had at first welcomed the outsiders – and their tools, blankets, liquor, guns, and medicines – they soon rued new diseases; a religion that called Indian ways wicked (for reasons less than clear); and most perniciously, the notion of private property. By the time Doc Maynard helped broker a deal to buy their land, they were in a weak bargaining position. In 1854, a proposal, the Port Elliott treaty, was put to the local tribes by a drunken Governor Stevens in Chinook Creole, a bastard tongue used by fur traders, more suited to rough commerce than diplomacy.

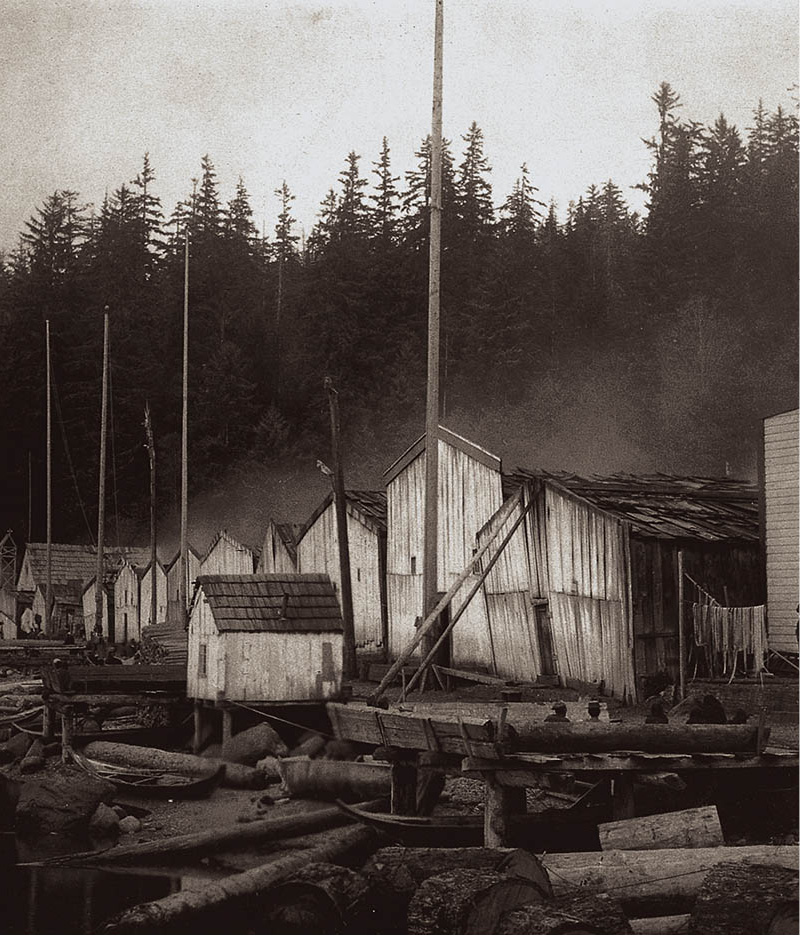

Native village, Alert Bay.

National Anthropological Archives

The US government offered the Native American tribes $150,000, paid over 20 years in goods, and a reservation, for 3,000 sq miles (8,000 sq km) of land. Chief Seattle answered on behalf of all the Indians in his language, Duwamish. Recalling the speech over three decades later, Dr Henry Smith was taken ‘with the magnificent bearing, kindness, and paternal benignity’ of Chief Seattle.

‘The Big Chief at Washington sends us word that he wishes to buy our lands but is willing to allow us enough to live comfortably,’ goes Smith’s version of Chief Seattle’s speech. ‘His people are many. They are like the grass that covers vast prairies. My people are few. They resemble the scattering trees of a storm-swept plain. Every part of this soil is sacred in the estimation of my people. Every hillside, every valley, every plain and grove has been hallowed by some sad or happy event in days long vanished, and when the last Red Man shall have perished and the memory of my tribe shall have become a myth among the White Men, these shores will swarm with the invisible dead of my tribe.’

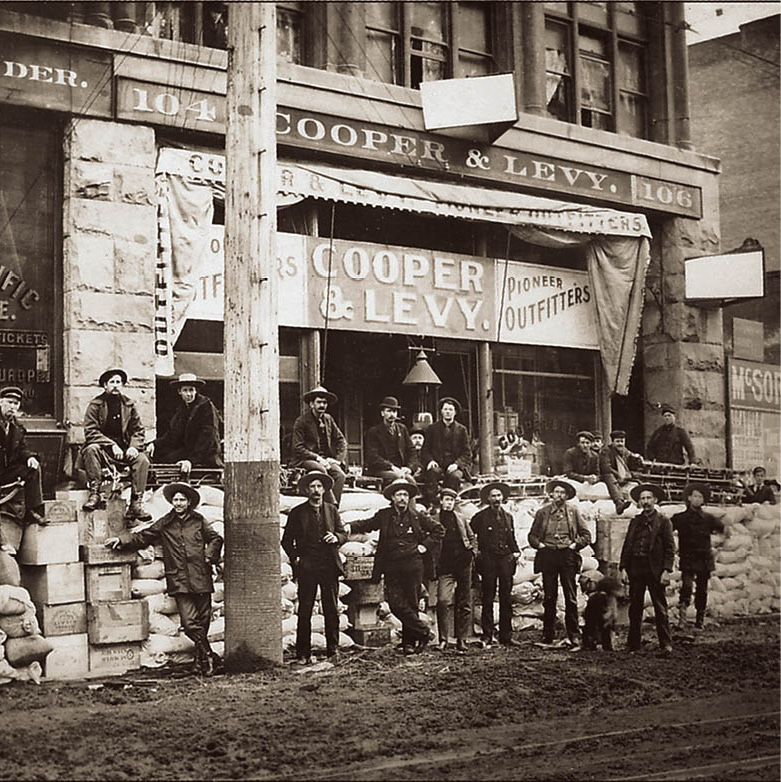

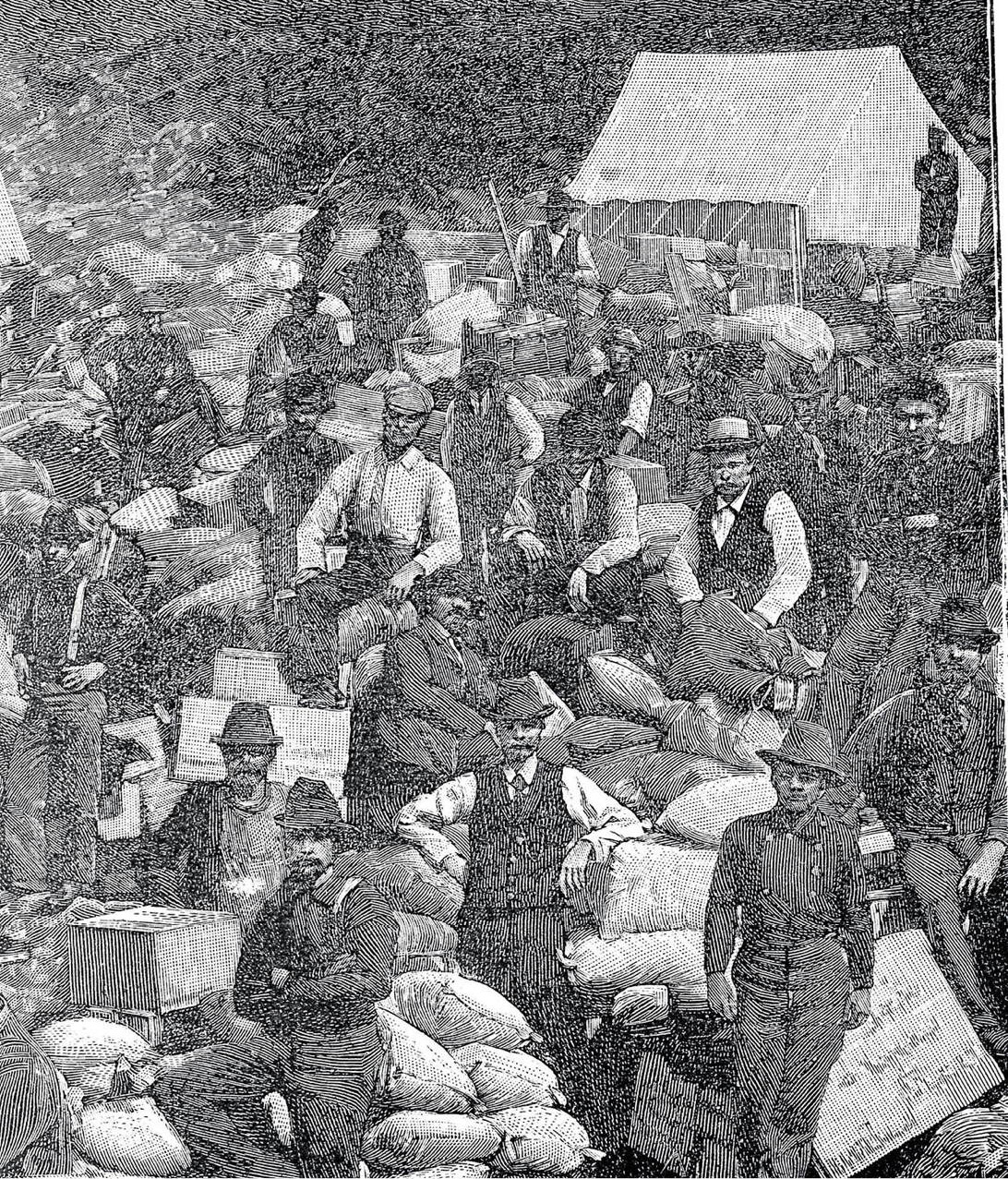

Anti-Chinese riot led by the Knights of Labor, 1886.

TopFoto

The next year the treaty was signed and most Native Americans moved to reservations across Puget Sound. In 1856, though, some rebelled. There were few casualties on either side, and the US Army easily defeated the small group. Leschi was a rebel Indian leader, caught by the perfidy of a nephew, tried and convicted of murdering an officer during the war, and hanged. The so-called Indian War was over and the whites had won, but many issues, like territorial fishing rights, remain disputed to this day. Leschi became a regional hero, with a neighborhood, a park, and a statue dedicated to his memory.

Seattle became an industrious village. While Yesler’s sawmill prospered, sending lumber to San Francisco and transferring sawdust to fill the swampy lowland, not everybody benefited to the same degree. Angeline, the daughter of Chief Seattle, worked as domestic help. ‘A good worker,’ said Sophie Frye Bass, niece of founder David Denny, ‘but when she had a fit of temper she would leave, even though she left a tub full of clothes soaking.’

The Great Fire of 1889 allowed the city fathers to rebuild a safer, better metropolis.

R.F. Zallinger/Museum of History and Industry

Racial problems

The mid-1880s were difficult times in Seattle. The city was hard hit by an economic depression afflicting the entire country. Out-of-work fishermen, lumber workers, and miners competed for jobs – not only with unemployed city clerks and carpenters, but also with the many Chinese laborers discharged after completion of the railroads. The Chinese workers became a scapegoat for the area’s problems. The hardworking Asian immigrants were resented by many unemployed Seattleites. The Knights of Labor, a white fraternal organization, wanted them ejected from the Northwest by force. In 1885, about 30 Chinese were driven out of nearby Newcastle. In early 1886 Seattle exploded in racial violence. Five men were shot, Chinese stores and homes were demolished, and 200 Chinese were forced aboard a San Francisco-bound steamer. By March, when federal troops restored order, the Chinese community of about 500 had been eliminated.

By 1890, Seattle’s population had more than quadrupled in a decade to 50,000. Three years later, the surge was over, but the city had become a very different place. Seattle was developing a sense of place, a personality, and an identity.

Miners pose on a Downtown street; the Yukon Gold Rush of 1897 made local merchants wealthy.

Historical Society of Seattle and King County/Museum of History and Industry

Nothing demonstrates Seattle’s ‘can-do’ attitude better than the city’s reaction to John Back’s blunder on June 6, 1889. Back, a handyman, threw a bucket of water on a flaming pot of glue in the middle of a paint store. The building exploded into flames, and 12 hours later the entire commercial district – 60 city blocks – was consumed.

Before the ‘Great Fire,’ the commercial section of Seattle had become a pestilential morass. The downtown area was built on mudflats, and sewers backed up when the tide came in. Chuckholes and pools of mud would open up at intersections, swallowing a schoolboy, horses, and even carriages. Typhoid and tuberculosis were rampant.

The fire allowed the overhaul of the municipal systems, and the city was rebuilt. Civic improvement began three days after the blaze, while the embers were still warm. Three years later, a new Seattle of brick and stone stood ready to lead the Pacific Northwest. New, higher roadways now reached the second stories of the buildings; people crossed the street by ladders. But the sidewalks and the ground levels 12ft (4 meters) below needed to remain accessible. This two-tier city is now the subject of a rambling, entertaining ‘Underground Seattle’ tour (for more information, click here).

New wharves, railroad depots, freight sheds, coal bunkers, and warehouses lined the mile-long waterfront strip. The sawmills moved out of town, leaving behind the name of Skid Road (now called Yesler Way). In later years, as this part of town became the haunt of homeless men and women, ‘Skid Row’ became a term used in other US cities to describe poor and urban neighborhoods of broken dreams.

For much of the 1890s, Seattle was in decline. Skid Road was becoming dangerous and derelict, and business slumped – until the arrival from Alaska of the SS Portland in July of 1897. Headlines screamed across the country the next day that the Portland docked bearing ‘A Ton of Gold Aboard.’ Seattle’s then-mayor, W.D. Wood, heard news of the Yukon gold strike while visiting San Francisco, wired his resignation, and headed straight for gold country.

Miners panning for gold in the Klondike, 1897.

TopFoto

Yukon Gold Rush

The mania swept the Western world, as men from Sydney to Switzerland uprooted their lives and headed to the frozen fields of the Yukon, far to the north. Many of these treasure seekers needed to pass through Seattle.

Tens of thousands of prospectors and unprepared fortune hunters hit the city, wanting supplies for their northbound adventure. Schwabacher’s Outfitters rose to the top of the provisioning industry, and supplies for the trek north were stacked on the boardwalk 10ft (3 meters) high. By the spring after the SS Portland’s arrival, Seattle merchants raked in some $25 million, against the previous year’s revenues of $300,000. Hotels and restaurants were overbooked and Seattle banks filled with Yukon gold. Schools taught mining and classes were even given in dogsled driving. This, in a city that rarely saw a snowflake.

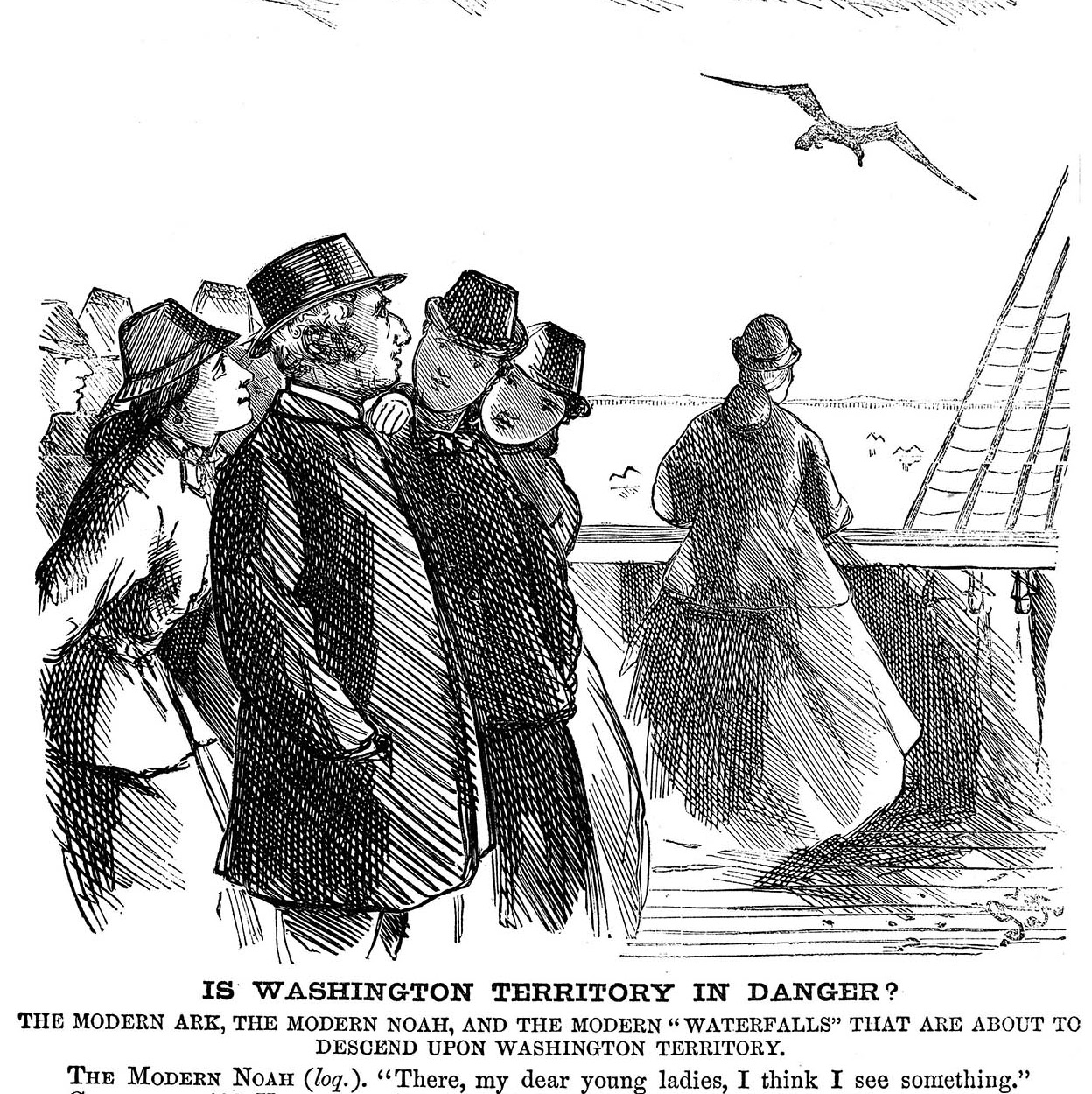

1866 cartoon mocking Asa Mercer’s importation of marriageable women to Seattle.

TopFoto

The transient Gold-Rush population craved entertainment. John Considine, patriarch of the famous acting family, opened up the People’s Theater and brought in famed exotic dancer Little Egypt, who, clad in diaphanous harem clothes, gave a lesson in international culture – the muscle dance, the Turkish dance, and the Damascus dance – for appreciative crowds almost every night of the year. Box-houses – so-called for the private alcoves at the sides of the theater – were a feature of Seattle’s nightlife.

Prostitution was a natural product of the mostly male lumber town. The demographic discrepancy between men and women led Asa Mercer, a carpenter on the newly built Territorial University (and its first president), to secure a $300 fee from lonely Northwest bachelors with the promise of marriageable young maidens from the East Coast. He aimed to bring 500 women, but returned to Seattle a year later with just 100. But Mercer managed to placate his male clients, married one of his imports, and moved inland.

Gold-diggers leaving for Klondike.

TopFoto

The Klondike Gold Rush also confirmed Seattle as the Northwest’s trade center, surpassing the older city of Portland, to the south. The boom raised Seattle’s population to 80,000 by 1900; with three railroad lines and a road over the Cascade Mountains, numbers rose to a quarter of a million by 1910. Swedes populated the then-separate sawmill city of Ballard (now part of North Seattle). Laborers from Japan came in large numbers in the late 1890s, foreshadowing Seattle’s later role as a shipping link to Asia and the Pacific.

By the beginning of the 20th century, Seattle had become a center for traffic in white slaves. Women were in great demand, many coaxed onto ships bound for the Northwest with promises of the good life.

The downtown area was regraded to reduce the inclines of the hills. Areas like Capitol Hill became neighborhoods of the utmost propriety. The high-class bordellos and cheaper ‘crib-houses’ were closed, and John Considine moved from his first box-house theater on Skid Road into a vaudeville-theater chain that soon extended across the United States. Alexander Pantages, who began as a bartender in a Dawson saloon and also ran a box-house theater, rivaled Considine’s chain.

The birth of Boeing

Seattle dominated the Alaskan shipping routes of the West Coast, and when the Panama Canal opened in 1914 and World War I brought increased demand for navy vessels, Seattle saw its future in shipbuilding and the sea. In 1910, at a makeshift airport south of Los Angeles, one wealthy Seattleite set his sights higher. The scion of a wealthy Minnesota iron-and-timber family with his own fortune from local timber, William Boeing attended the first US international flying meet.

Boeing’s initial interest in flying may have been on a par with his purchase of the Heath shipyards just in order to finish a yacht, but over Lake Washington, while testing a Curtiss-type hydroplane he built with friend and fellow Yale graduate George Conrad Westervelt, he found a profession and a mission. In 1916, the company was incorporated in Seattle.

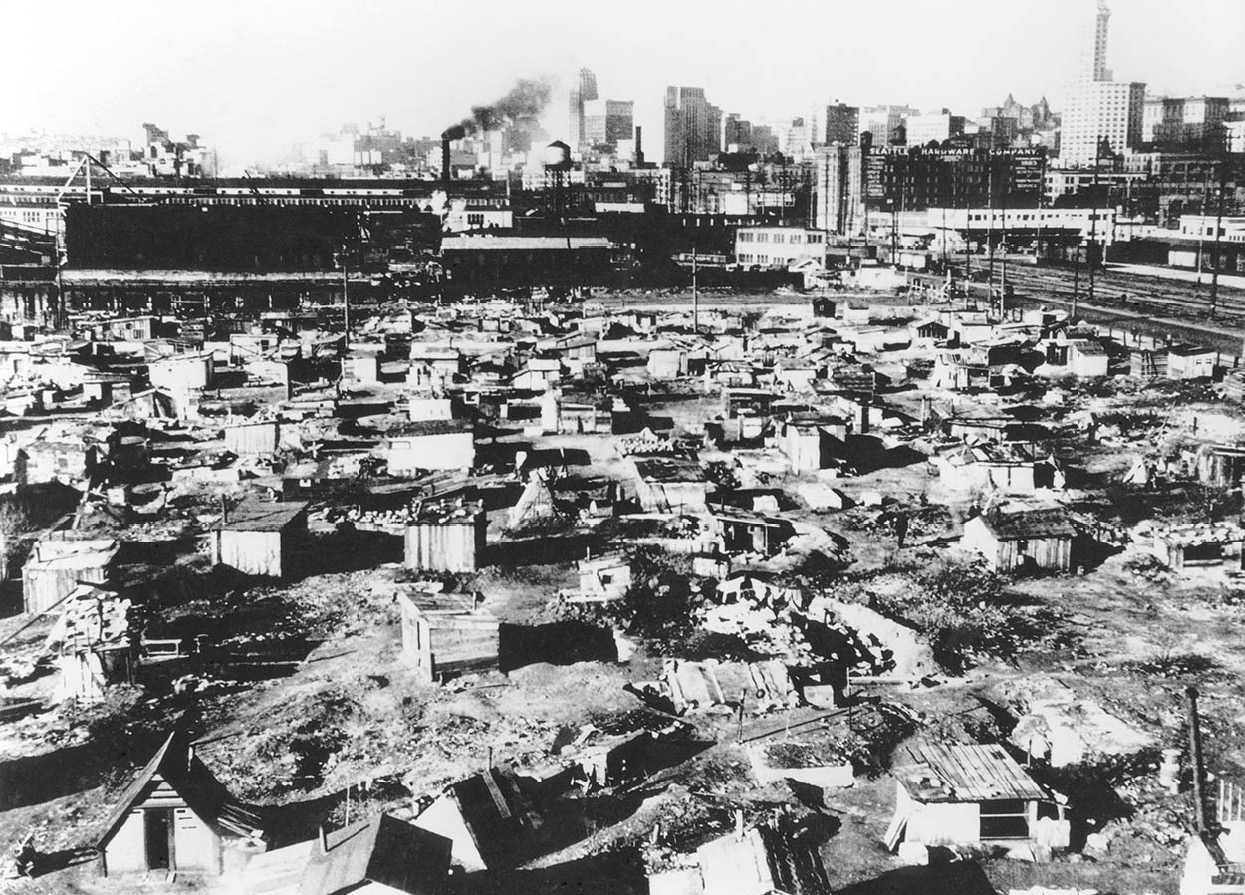

In the early 1930s, the economic body blow that followed the Great Depression hit Seattle harder than most cities. Skid Road saw an ever-growing population of the haggard and the hungry. A meal cost only 20 cents, but few on Skid Road could afford it. Still, there was order among the destitute.

Bertha Knight Landes was elected mayor in 1926. She was the first female elected executive in a major American city, and the only woman to date who has held the position of Seattle’s mayor.

The city’s so-called Hooverville (Depression-era shantytowns were named after then-President Hoover), built on the tide flats in an abandoned shipyard, was among the largest temporary communities in the US. It had its own self-appointed vigilante committee to enforce a sanitation code. The Unemployed Citizens’ League reached a peak membership of 50,000 in 1931, and formed a separate community – called the Republic of the Penniless – with a system of work and barter to feed and house its members. Those lucky enough to hold jobs were members of a network held in lock step with the powerful Teamsters union.

When non-union beer from the East Coast appeared in the Seattle area, teamsters refused to move it from warehouses. Local breweries benefited, helping to establish the strong Seattle tradition of regional breweries.

Seattle shantytowns, 1933.

TopFoto

Big bombers and the Jet Age

World War II brought Seattle’s next great economic boom. Although based partly on shipbuilding, this time the recovery was centered predominantly on one industry – aircraft – and one company – Boeing. Borne on the wings of Boeing’s mass-produced B-17 Flying Fortress and B-29 Super Fortress bombers, the 1940 greater metropolitan population of about 450,000 continued to grow. But the economic benefits didn’t extend to everyone; the war and Japan’s bombing of Pearl Harbor brought misery to the local Japanese population.

When President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 in February 1942, 110,000 Japanese were summarily removed from their jobs and homes and interned in camps along the West Coast, Wyoming, and Idaho. In Seattle, 7,000 Japanese lost everything they owned and spent the next three years in an Idaho camp.

A Boeing 707, the USA’s first successful commercial jet, flies over Mount Rainier in 1954.

Topforo

Yet, like the Chinese before them, many Japanese returned to Seattle after the end of the war, even though their property was taken and despite the racism they encountered almost daily.

In the 1950s Seattle’s economy also benefited from the Korean War, with growing demand for B-47 and B-52 bombers. The civilian 707 launched Seattle’s confident entry into the Jet Age.

Nothing symbolized this better than the landmark of the skyline, the Space Needle, built for the 1962 World’s Fair in Seattle. The Century 21 Exposition, as the fair was named, left a lasting legacy of futuristic structures for the people of Seattle, not just with the Needle but with the entire Seattle Center, including the Pacific Science Center, the International Fountain, indoor and outdoor concert venues, and the Monorail that connects Seattle Center with Downtown.

The World’s Fair of 1962 was responsible for Seattle’s most prominent landmark, the Space Needle.

Historical Society of Seattle and King County/Museum of History and Industry

By 1965, the population had grown to more than half a million. Despite the massive lay-offs at Boeing in the late 1960s, Seattle continued to be a draw for newcomers. Attempts were made to raze older sections of the city, but the growing population was fostering an interest in preservation and renovating what remained of old Seattle. Civic visionaries saw to it that Pioneer Square was designated a National Historic District, preserving its unique architectural character. One notable hero of preservation was the architect Victor Steinbrueck, who led a citizens’ campaign to save the Pike Place Market from the wrecking ball of developers. In 1971 the first branch of Starbucks opened in the market, selling dark-roasted whole-bean coffee.

It was also during this decade that the first major festival of music and arts took root. Later to be known as Bumbershoot, it has since become the city’s largest and most popular festival, held every Labor Day weekend. In 1978, the Seattle Art Museum mounted the hugely successful King Tut exhibition, which attracted 1.3 million visitors and gave SAM the impetus to think bigger, including plans to move from Volunteer Park in Capitol Hill to Downtown. The 72,000-seat Kingdome was built as a venue for Seahawks football, major rock concerts, and trade shows for boats, RVs, and much more.

The region’s economy was continuing to diversify. By 1979, the young Microsoft company moved from Albuquerque to the Eastside city of Bellevue, Washington, returning to the area where its founders, Bill Gates and Paul Allen, were raised. Now the Puget Sound area was home to logging, spearheaded by the Weyerhaeuser Corporation headquartered in the southern suburb of Federal Way, aerospace engineering, and the fledgling high-tech industry.

Crushed car and flattened bare trees in the aftermath of Mount St Helens’ 1980 eruption.

Photoshot

Fire Mountain explodes

On May 18, 1980, nature took a stab at containing the growth of Seattle and the Pacific Northwest itself when Mount St Helens, south of Seattle, lived up to its Native American name of Fire Mountain. After 200 years of being virtually dormant, 9,677ft (2,950-meter) Mount St Helens erupted, sending much of the mountain’s summit 60,000ft (18,000 meters) into the air.

The eruption came after warnings from scientists and attempts to evacuate the area, but the flow of molten rock and clouds of ash still resulted in as many as 60 deaths. Damage was estimated at $1 billion. Within three days, the ash cloud had crossed North America; within two weeks, it had traveled right around the globe. Mount St Helens itself became 1,300ft (400 meters) shorter than it had been before the blast. Ash fell throughout the Northwest in heavy amounts, hindering transportation, industry, and – in the short term – agriculture. Ultimately, the ash injected nutrients into the soil, as it has throughout the formation of the earth’s lands.

Other factors were also contributing to the changing landscape. In 1986, Microsoft went public, and the ensuing rise of the stock price created thousands of millionaires. In 1981 Starbucks hired Howard Schultz, who led a group to purchase it in 1987. It would go on to become one of the world’s best-known brands, selling coffee across the globe.

In a bid to attract more business to the city, the Washington State Convention Center opened its doors in downtown Seattle, creating a large central venue for conferences and conventions. A subsequent expansion doubled the meeting space capacity, and hotel space in the city center also continued to grow.

Seattle’s annual Bumbershoot arts and music festival.

Dreamstime

Logging and protests

During the 1990s Seattle grew less economically dependent on logging and on aerospace, becoming a high-tech mecca for companies such as Amazon and Nintendo of America. Even after the dotcom bubble burst, these companies stayed strong.

In 1994, Pioneer Square-based Aldus Software, maker of popular programs such as PageMaker and founded by Paul Brainerd, merged with Adobe Systems and set up shop in the Seattle neighborhood of Fremont.

Jeff Bezos launched his online bookstore, Amazon, in 1995, and soon added software, CDs, movies, and video games. The company, headquartered at the time in a former hospital on Beacon Hill, survived the ‘dot bomb,’ but remarkably didn’t turn its first annual profit for another eight years.

In 1990 Seattle hosted the Goodwill Games, with 2,300 participants from 54 countries. The event was held in reaction to the political troubles and boycotts over the 1980s Olympic Games.

Starbucks continued to go from strength to strength, too. The first Starbucks outside North America opened in Tokyo in 1996, and today the company sells coffee in more than 60 countries.

The explosive growth in high-tech industries produced scores of young millionaires, as well as changes in the local landscape. Local boy Bill Gates became the richest man in the world in 1993 (for more information, click here). Paul Allen, who had stepped out of day-to-day operations at Microsoft a decade earlier, spent huge amounts of money in civic projects around the Puget Sound area. He purchased and began preservation work on Union Station, a century-old Seattle landmark. He bought the Seattle Seahawks football franchise, securing the team’s future in the city, and constructed a world-class stadium and exhibition center on the site of the old Seattle Kingdome, adjacent to Safeco Field, the state-of-the-art baseball stadium that opened in 1999. He also founded the EMP Museum, a dynamic interactive music museum designed in high style by architect Frank Gehry (for more information, click here).

Bill Gates and Microsoft

One of the world’s wealthiest men, the co-founder of Microsoft is now focused on bringing advances in health and education to communities around the globe

William H. Gates III, the son of a successful Seattle attorney, was born on October 28, 1955. Prodigious in math and science, he gained programming experience at the city’s prestigious Lakeside School. At the age of 19, taking time out from Harvard, he founded Microsoft with an old friend, Paul Allen. Microsoft’s phenomenal success is rooted in a 1981 coup to supply operating systems for IBM’s new line of personal desktop computers. They licensed a system known as QDOS (Quick and Dirty Operating System), adapted it to produce PC-DOS, and effectively created a stranglehold on the nascent PC market. In 1986, Gates sold some of his stock at $21 a share; in 1999, he sold nearly 10 million shares at $86 a share. In its heyday, Gates’ worth increased by an average of $1 million a second.

Much is made of Gates’ and Allen’s wealth, but scores of employees also made millions through stock options. In the 1990s, the neighborhoods around Microsoft’s headquarters in Redmond were (and still are) lush with dotcom success stories.

Microsoft’s power base is still the Windows operating system, but as the internet gained momentum in the mid-1990s, Gates steered the company’s focus toward the net. Fearing the browsers of Netscape and AOL could relieve users’ dependence on Windows, Microsoft began the ‘browser war’ by creating Explorer. It also allied with NBC to create the cable-TV and online news service MSNBC and bought web businesses, from WebTV to Hotmail.

Microsoft today

IBM and Microsoft parted ways long ago, but Microsoft has gone from strength to strength. The operating system that powers more than 90 percent of the world’s PCs makes Microsoft formidable. The company took a big and lucrative step into the games-console market with the Xbox, and is tilting at Apple’s iPhone market its Windows Phone series and the Kin smart phone aimed at young people.

Such staggering success has not gone unopposed. Microsoft attracted massive antitrust suits from both the US Government and the European Union, and there have been battles over copyright theft in China; open-source movements in South America; and the open-source operating system, Linux. But as a company that is still wealthier than all but half-a-dozen countries in the world, Microsoft is unlikely to be in any danger. In 2008 Gates stepped down from running the company full-time, handing the reins over to Steve Ballmer, in order to administer the charitable Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, which he established with his wife. The impressive Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation Visitor Center, across the street from Seattle Center, opened to the public in February 2012.

Bill Gates, founder of Microsoft.

World Economic Forum

These are only some of many ambitious projects the city launched in the 1990s. Both the Seattle Art Museum and Benaroya Hall, home of the Seattle Symphony with a 2,500-seat concert hall and highly enviable acoustics, helped to revitalize Downtown.

But it wasn’t just in the upper echelons that the arts were thriving. A local sound that had been gaining momentum since the late 1980s, grunge now burst onto the world music scene, with bands including Nirvana, Pearl Jam, Soundgarden, Alice in Chains, and Mudhoney, and record label Sub Pop creating the phenomenon that was nicknamed ‘the Seattle sound.’ This brought a new cachet to the city, and scores of young people and musicians headed to Seattle.

Seattle Art Museum.

Ben Benschneider/SAM

Protests and anti-globalization

Another pivotal event that focused the world’s attention on Seattle was the World Trade Organization protest-turned-riot. In 1999 the WTO held its ministerial meeting at the Washington State Convention Center. A broad range of activists, made up of environmentalists, human rights activists, trade unionists, and pro-democracy campaigners came to protest against what they perceived to be abuses by the WTO’s trade practices. Although the city, Seattle police, and WTO organizers expected the protests, nobody was prepared for what followed, dubbed the Battle in Seattle. Clashes between police and protesters turned violent, tear gas was sprayed into the crowd, property was damaged, protestors were injured, arrests were made, and Mayor Paul Schell declared a state of emergency and ordered a curfew. The National Guard and the Washington State Patrol were called in to restore order. The mishandling of the situation ultimately led to the resignation of the chief of police.

In another contentious arena, the tension between environmentalists and the logging industry had been growing. In the 1990s, environmentalists had some cause for optimism. Activists began to see some success in halting the clear-cutting of ancient forests. The US Forest Service was becoming more environmentally sensitive and more responsive to public desires. Pressure groups forced the government of nearby British Columbia to cancel logging rights and to protect some magnificent, centuries-old, first-growth, temperate rain forests, principally on southwest Vancouver Island. Last-minute decisions made by outgoing president Bill Clinton in 1999 included a moratorium on new forest road construction on nearly 60 million acres (24.3 million hectares) of national forests – used as access roads for timber companies – as well as a program to close many such roads and to restore them to a natural state.

But America under President George W. Bush saw a roll back on environmental protections. The Bush administration revised Clinton’s plans, causing outrage among environmentalists and relief among lumber companies. A report presented by US Forest Service chief Dale Bosworth in 2002 criticized specifically the Northwest Forest Plan – implemented by the Clinton administration – to balance timber harvests and wildlife preservation in the region.

Anti-WTO protestors hit the streets in 1999.

TopFoto

21st century and more

A magnitude-6.8 earthquake struck the Seattle area in February 2001, and caused property damage throughout the region, including to the Capitol building in Olympia. The epicenter of the quake was about 10 miles (16km) northeast of Olympia, and 32½ miles (52km) underground. Unlike many regions on the continent, the Pacific Northwest coastal area has constant reminders of its geological history and origins.

That year Seattle suffered another seismic shock; this time when Boeing moved its corporate headquarters to Chicago, cutting 20,000 jobs in the process. The regional economy had become less dependent on Boeing over time, but the company still has a sizeable presence in the area.

Seattle’s latter-day phenomenal success has been at some cost, however. It has a dubious distinction as one of the nation’s worst cities for traffic. The Interstate-5 corridor is particularly crowded. The Alaskan Way viaduct, a 1950s concrete double-decker roadway running along the waterfront and past Pioneer Square, was damaged in the earthquake and after heated debate is being replaced by an expensive tunnel, but it gives Seattle the chance to change the Waterfront landscape, and to connect it with Downtown, removing the roar of traffic, too.

50 Shades of Seattle

Cuffs, paddles, and ropes, oh my! With her best-selling trilogy, 50 Shades of Grey writer E.L. James drew attention away from the small town of Forks on the Olympic Peninsula (made famous by the Twilight series) and put it squarely on Seattle, where her three lusty S&M-themed books take place. In the story, Christian Grey’s condominium (home to his ‘Red Room of Pain’) is in the Escala – an actual building in Downtown Seattle. Several local hotels (including the Edgewater and Hotel Max) offer 50 Shades of Grey-themed packages.

Neighborhoods have changed. House prices have risen. But then so have fantastic new buildings. The city’s skyline has been complemented by a new home for the city’s football team, CenturyLink (formerly Qwest) Field (2002), and the Olympic Sculpture Park (2007).

The Washington State Ferries terminal, the Seattle Art Museum, and the Seattle Aquarium have been expanded or remodeled. The Rem Koolhaas-designed Seattle Public Library opened in 2004, with new neighborhood branches in Ballard, Greenwood, and Montlake. Better transportation links are underway, with light rail and streetcars both expanding their services.

The Seattle skyline at night from the Space Needle.

Nathaniel Gonzales/APA Publication

Sports, too, have become big business. Starbucks CEO Schultz endeared himself to Seattleites by leading a group to buy the city’s basketball team, the SuperSonics, in 2001, but incurred their wrath by selling the franchise – including its women’s team, the Seattle Storm – in 2006. The Sonics were bought by a group of Oklahoma businessmen, and left town, while a local group of businesswomen bought the Storm, securing its future in Seattle. The Seattle Seahawks fought their way to the Super Bowl in 2006, but lost to the Pittsburgh Steelers. Meanwhile, the Sounders FC, the city’s wildly popular soccer team, has a loyal fan base.

In 2009, after one of the worst winters, with the most snowfall on record, in which the city’s snowplows failed to keep traffic moving, Mayor Greg Nickels lost a hotly contested election to environmental activist Mike McGinn.

During the elections of 2012, Washington voters not only helped to award Barack Obama another term in the White House, they also approved same-sex marriage and the legalization of marijuana. Building projects have sprung up across the city, with seemingly every vacant lot being dug out and constructed upon. Today, ongoing challenges face local government, including improvements to public transportation and road infrastructure, and balancing large-scale projected growth with environmental impacts in order to keep Seattle the highly livable, resilient, and beautiful city that it is.

The exterior design of the Seattle Central Public Library.

Nathaniel Gonzales/APA Publication