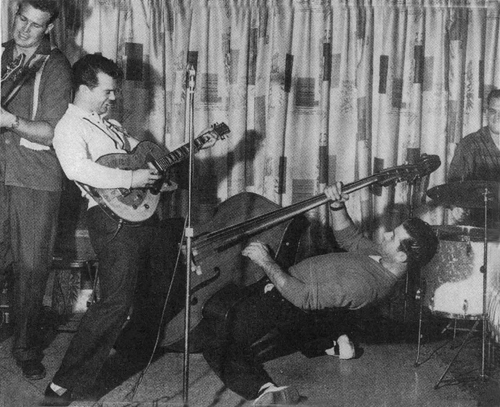

Lavon Helm, age thirteen, hamboning at a 4-H Club talent show in Phillips County, Arkansas, circa 1953 (TURKEY SCRATCH ARCHIVES)

Rosemarie Crysler was a beautiful Mohawk Indian girl from the Six Nations reservations above Lake Erie. After World War II started she came to Toronto to live with an aunt and met a guy named Klegerman, with whom she had a son in July 1943, Jaime (pronounced Jamie) Robert. Mr. Klegerman was a professional card player and gambler, as his son later described him. He was killed while changing a tire on the Queen Elizabeth Way between Toronto and Niagara Falls when his son was a baby. Robbie’s mom married a Mr. Robertson, and they both worked in a jewelry-plating factory while Robbie was growing up.

The boy spent his summers on his mother’s reservation, surrounded by cousins and uncles who played fiddles, mandolins, and guitars and laughed a lot. His great-grandfather would grab the boy with the crook of his cane as he ran by, tell him stories and lore, trying to make a Mohawk out of him. His mother took Robbie for guitar lessons when he was ten; the Hawaiian instructor laid a guitar on his lap and taught him to play it flat, Waikiki style. It was the only training the boy ever had. Meanwhile he stayed up all night listening to WLAC out of Nashville, a fifty-thousand-watt clear-channel station with a thousand-mile range. Deejay John R. played blues all night in the 1950s. It was the underground radio of the day. There was also George “Hound Dog” Lorenz, a rock and roll disc jockey in Buffalo whose show was influential for a lot of young Canadians.

Robbie liked school until he caught the rock and roll bug. At thirteen he was in a band called Little Caesar and the Consoles, playing New Orleans songs like “Blue Monday.” Then he formed Robbie Robertson and the Rhythm Chords around the time the now-classic sci-fi movie Forbidden Planet came out, featuring Robbie the Robot. So Pete Traynor, one of the Rhythm Chords, drilled some holes in Robbie’s Harmony guitar, installed some antennae and wires, and they renamed the group Robbie and the Robots. Then there was Thumper and the Trambones. At fifteen Robbie Robertson was a tall, dark street-smart punk living with his mom in Toronto’s Cabbagetown neighborhood and hanging out on Yonge Street, catching the bands that came through town: Bo Diddley, Carl Perkins, Ronnie Hawkins. That’s when we met him.

Robbie, Pete Traynor, and a piano player named Scott Cushnie had this little band, and they opened for the Hawk one night at Dixie Arena. The Hawks, Robbie told an interviewer, “played the fastest, most violent rock and roll I’d ever heard. It was exciting and exploding with dynamics. The solos would get really loud, Ronnie would come in and growl, then it would get quiet, then fast and loud again. It was these cool-looking guys doing this primitive music faster and more violent than anybody, with overwhelming power.

“It was also the way they looked, how young they were. They weren’t as young as me, but they were still pretty young. There was this little kid playing drums. You couldn’t believe this guy was the drummer, but he was terrific. Terrific to look at and terrific to hear….

“I knew the majority of the music I liked and felt connected to was from the South,” Robbie continued, “and they kind of represented that to me. And Levon didn’t let down my fantasy of what this thing was. He was real, authentic, and had such a love for music. To me it seemed he came right from Mecca.”

The Hawk took a liking to this kid. One afternoon I came into the club, and Robbie was auditioning for the Hawk, playing him a couple of songs he’d written. That night Ronnie said to me, “Son, y’know that kid who’s been hanging out? He’s got so much talent it makes me sick! Maybe we should take him on.”

I pointed out that we already had a couple of guitar players.

“Yeah,” the Hawk said, “but Luke’s going home soon, and this kid can write a little. Besides, I know his mom. She’s worried about him, and maybe if we take him on, it’ll keep him out of jail. Let’s think about it.”

We didn’t hire Robbie right away, but the Hawk took him along to New York when we cut our next tracks at Bell Sound. He sat next to me in the Cadillac and talked my ear off as I drove down the “Queen E.” Jesus, this kid really wanted to be in the band. I got the impression he’d kill for a permanent seat in the Cadillac. Of course, I would’ve too.

One reason the Hawk took Robbie to New York was that he trusted Robbie’s ears. Robbie was opinionated about hit records, and Ronnie figured since the kid was still a teenager, what Robbie liked would also appeal to the teenager rock and roll market. We were looking for that big hit, right? So while I went over to the Metropole Cafe on Seventh Avenue to check out Cozy Cole or Gene Krupa, Hawk and Robbie went over to the Brill Building on Broadway and met some of rock and roll’s biggest songwriters—Doc Pomus and Mort Shuman, Jerry Leiber and Mike Stoller, Carole King and Gerry Goffin, Otis Black-well—and auditioned a hell of a lot of songs. “That wasn’t bad,” the kid told Mort “Save the Last Dance for Me” Shuman. “You got anything else?”

The Hawk cut two of fifteen-year-old Robbie Robertson’s tunes with Henry Glover on October 26: “Hey Boba Lou” and “Someone Like You,” as well as “Baby Jean” (cowritten by me) and nine other tracks. These came out on the Hawk’s second album, Mr. Dynamo, which Roulette released in January 1960.

The Hawk told anyone he could that this kid Robbie was going to be one of the biggest stars in the business some day. Ronnie had us all convinced. Nevertheless, he told Robbie he was too young to be in the band.

Late in 1959 Willard wanted to go back to Arkansas for a while; not quit the band, just take a leave. The Hawk replaced him with Scott Cushnie from Robbie’s band, who finished a gig we had at the Brass Rail in London, Ontario. Luke went home, deeply mourned by the Hawk, who maintains to this day that Jimmy Ray Paulman was the best rhythm guitar player in the history of rock and roll, bar none. Then Lefty Evans quit while we were working down in Arkansas. As a going-away present for him, I picked up two cherry bombs for a dollar. While Lefty was asleep in the Cadillac, I lit the fuse of one of the big firecrackers, tossed it in the backseat, and shut the door. The hissing fuse woke him up, and Lefty tried to stomp it out, but the fuse kept burning. I could see Lefty’s fingertips just reaching the door handle when it went off. Then he tumbled out of the car amid thick smoke and flying bits of paper.

We were cruel to one another in the band.

Fred Carter, Jr., took over lead guitar, and Robbie Robertson was called down to Arkansas to play bass. It might have been Scott who suggested Robbie.

The Hawk called Robbie at his mother’s house from his nightclub in Fayetteville. “Son, can you play any bass?” he asked.

“Yes sir,” Robbie lied.

“Start practicing. I’ll call you next week.”

The Hawk didn’t call. A few weeks later Robbie reached him at the Rockwood Club. “OK, come on down,” Ronnie told him. “I’m gonna put you in training. Maybe we can break you in.”

Robbie begged, pleaded, and lied until his mom let him go. There was no money for bus fare, so he pawned his ’57 Fender Stratocaster. He took one bus from Toronto to Buffalo, than another to Chicago, then a train to Springfield, Missouri, and another bus up winding Ozark roads to Fayetteville. When Robbie got off the bus, Ronnie and his friends simply laughed at this city kid wearing a long overcoat. It was hot in Arkansas in December. “You look like an immigrant from Albania,” the Hawk told him. Ronnie took the kid to the barber, got him cleaned up, bought him some new clothes, and explained that he and I were going to England to be on TV, and if Robbie practiced real hard while we were gone, he might have a spot in the band when we came back. “Nobody knows if you’ll be good enough,” he told the kid. “We’ll see how it works.”

Then he put Robbie on a bus to Helena.

Up in Fayetteville, the Ozark mountain air was clear and fresh. As Robbie’s bus came out of the mountains, down through Little Rock, he saw the landscape flatten. The light changed as it filtered through the delta dust. Everything was low and wet, with rice growing in fields of water. “People walked in rhythm and talked this singsong talk,” he remembered. “When I’d go down by the river in Helena, the river seemed to be in rhythm, and I thought, No wonder this music comes from here: The rhythm is already there.”

I picked Robbie Robertson up at the bus station and drove him out to Turkey Scratch. “How come your house is up on stilts?” he wanted to know. Diamond was still farming cotton on some land he owned and some he leased. Linda was still at home, and my brother Wheeler was only about ten. Momma made Robbie supper, and he told her it was the best meal he’d ever had. I bet it tasted good, after ten hours on that bus. Diamond told some funny stories, and Robbie about split his sides. Then Diamond got out his mandolin, and we all might have sung a little, with Robbie playing my guitar. Later that night we drove back into Helena, and Robbie looked around with his mouth open.

“It’s like being in another world,” he said. “I never saw so many black people in my life. It’s like Africa.” I explained that down here in the delta there were eight black people to every white. Robbie didn’t say anything. He sat in the passenger seat and stared into the darkness of the night.

In January 1960 Morris Levy flew Ronnie and me to London. Rockabilly hadn’t died in England like it did back home, and Ronnie had a following, especially, we heard, up in Liverpool. Before we left, the Hawk gave Robbie a hundred dollars to live on, and he and the rest of the band moved into Charlie Halbert’s motel. Fred Carter, Jr., was supposed to teach Robbie a few things while we were away; instead Fred took him up to Memphis, to the famous Home of the Blues record store on Beale Street, and Robbie spent his allowance on blues and R&B records. Fred also took Robbie to Sun Records, where Jerry Lee Lewis was recording. I’m here, Robbie said to himself. I made it.

In England we appeared on an early BBC pop-music show called Boy Meets Girl and got to hang out and jam a little with Eddie “Summertime Blues” Cochran, who was also big in England and touring at the time with the Shadows, a good British band. I was astonished by Eddie’s ability to chord a guitar using his little finger as a bar. It was something else! Eddie Cochran was a hell of a rocker; we were saddened a short time later when we heard he’d been killed in a car accident over there. (I almost got killed myself in London when I stepped off the curb after looking the wrong way for oncoming traffic. I’d forgotten the British drive on the left!)

Meanwhile, back in Helena Robbie was picking apart Howlin’ Wolf records for their bass and guitar parts. He practiced twelve hours a day until his fingers were hard as nails. Robbie remembered the Hawk pumping him up, telling him how good he was. He thought about Ronnie’s mercenary, out-for-blood attitude toward the music business, and realized that Fred Carter wasn’t exactly killing himself as a guitar teacher. Robbie realized he was fighting for his life. “There was no way,” he remembered, “that Ronnie was gonna come back and say, ‘This ain’t working out.’”

The Hawk and I returned home and couldn’t believe the progress Robbie had made in two weeks. We started rehearsing and would sit up all night deciding what to do with the band.

Charlie Halbert had a big mansion up on a hill, and he let us rehearse in his living room, which had a good piano. Robbie watched Fred work his Fender Telecaster. He had replaced the two bottom strings with steel banjo strings, a trick that gave his sound a real bluesy twang. Robbie picked up all this stuff and absorbed techniques from everyone, even transposing some of Ray Charles’s piano licks for electric guitar. One night we sat down and played Ronnie’s big ‘numbers—“Mary Lou,” “Hey! Bo Diddley,” “Who Do You Love”—and Robbie was pumping the bass lines. Hell, I wanted to get up and dance, it sounded so good.

When we finished rehearsing that first night, the Hawk looked at me and said, “This cat’s a genius.” He turned to Robbie. “Son, you got the job. Stick with us, and you’ll get more nookie than you can eat.”

In the winter and spring of 1959-60 Ronnie Hawkins reached a turning point. Morris Levy wanted him to stay in New York and take over rock and roll, maybe go to Hollywood. “You can’t go back to Canada!” Morris shouted at us in his office. “You’ve got it all to yourself. Elvis is in the fuckin’ army, and you’re better than him anyway now. Buddy Holly, Eddie Cochran—dead. There’s a vacuum here, and you’re the only one around who can take advantage of it. You’re on the goddamn verge! You can’t just vanish on me.”

But the Hawk wasn’t as sure as Morris was. If you watched American Bandstand that year you saw who was taking over: Dick Clark’s new teen idols, like Frankie Avalon, Fabian, Bobby Rydell. Italian kids from Philadelphia with big hair. When the big payola scandal hit the front pages a few months later, Alan Freed’s career was over, and with it the rock and roll business we’d come up in. Hell, the fifties were over. Meanwhile, the Hawk had been investing. He owned a couple of clubs in Fayetteville and had bought two farms in the area. These required cash flow. We’d worked for almost two years building a lucrative circuit in southern Ontario and Quebec. Hawk knew that in Canada he could work seven nights a week all year and be guaranteed a living that the changing American music business might no longer provide.

I felt the way the Hawk did. By then my dad had quit farming, and Momma was working in a department store. I’d been sending money home every week since I went with Ronnie, so my own family was dependent on the Hawk’s working steadily. There were so many bars between Windsor, Ontario, and Montreal that I knew we could work every night of the year. Unlike Luke, Lefty, or Willard, I didn’t have a girl back home. In fact, I was getting extremely infatuated with the Canadian girls. By all means, I agreed with the Hawk, let’s get back to Toronto and be the big fishes in the littler pond.

Morris Levy couldn’t believe it. “Hawkins moves better than Elvis,” he told me. “He looks better than Elvis and sings better than him too, if you ask me. Why don’t you talk to him?”

I had tried. So had Henry Glover. Even the Colonel. Morris was mystified. “He keeps saying how much he loves Canada,” he told me. “It’s breaking my heart.”

We went back to Canada with Robbie in the band, playing bass. He told me later his whole outlook had changed in Arkansas. “I’d hear something at night and not know whether it was an animal, a harmonica, or a train,” he remembered, “but it sounded like music to me. And every day the radios would go, ‘Pass the biscuits! It’s King Biscuit Time!’ and you’d hear this harmonica—‘waa, waaaah’—and it was Sonny Boy Williamson. The jukeboxes were like being in heaven, but what blew my mind was that in the places we played, the audiences weren’t just a bunch of kids, it was everybody. Old people too, from the richest to the poorest, checking it out and getting crazy. I’d never even seen a beer flow like this.”

Back at the Warwick Hotel in the hooker district, we were happy to be home. That’s when the great Stan Szelest from Buffalo came into the band. Ronnie thought we sounded thin when Luke left, so he hired seventeen-year-old Stan to play piano. (The Canadian bar owners didn’t like hiring Canadian musicians. Rock and roll came from the States, and that was all a tavern owner in Simcoe, Ontario, or Quebec City wanted to know.)

Stan was a Memphis-style musician with that full muscle in his playing. His group, Stan and the Ravens, were rock and roll in Buffalo, and Stan had made his bones on the road playing behind Lonnie Mack in Pennsylvania’s mining and steel towns. Stan was young, but he was already a star-quality musician. He was big and good-looking, and I was happy because Stan and Robbie were closer to my age than Luke and Lefty, who were closer to the Hawk’s advanced age of twenty-five. We took Robertson and Stan over to Lou Myles and bought ’em a couple of black mohair stage suits. Once Lou made your suit, you were officially a Hawk.

With rockabilly a dying form, Ronnie tried to stay even with the changing times, which led to some funny things happening. Rock and roll was still good business in Canada (we were making five hundred dollars a week, top money for a band in those days), but the younger kids were being converted to the folk-music revival sweeping North America in the wake of the Kingston Trio. Canadian folkies like Ian and Sylvia and Gordon Lightfoot were drawing to the coffeehouses in Toronto’s Yorkville district crowds as big as the ones we were bringing to Yonge Street.

So in March 1960 we were back in Manhattan recording folk songs for Morris Levy. Ronnie sang “John Henry,” “Motherless Child,” and “I Gave My Love a Cherry.” He even cut a protest song, “The Ballad of Caryl Chessman,” about the condemned killer whose rehabilitation in prison stirred up those against capital punishment. Henry Glover brought in jazz bassist George Duvivier to back Ronnie, and Roulette released Folk Ballads of Ronnie Hawkins in May 1960.

Spring and fall were the times we went back to Arkansas. Working out of Fayetteville, we made our rounds. At the Club 70 near Little Rock they did a heavy trade in amphetamines in the parking lot. The place, torched and repeatedly rebuilt like so many Arkansas honkytonks, was between the city line and the Air Force base at Jacksonville. Inside you’d get a volatile mix of northern kids from the base and locals from Little Rock, and soon chairs would be flying over our heads. After the show we’d head into the Ozarks to play a college dance in Fayetteville or a frat party in Norman, Oklahoma, where we’d have to wade through a knee-high river of beer cans to get to where we were set up.

We had a friend there named Dayton Stratton, who co-owned the Rockwood Club with the Hawk. Dayton was also a manager and a booking agent, and he helped us with security. If we were putting on a dance in Norman, he’d hire some wrestlers from the University of Oklahoma to keep things relatively peaceful.

Dayton was the ultimate southern gentleman—until you riled him. I’d see him beg people to stop fighting and just sit down and enjoy the music, but sometimes they wouldn’t listen. If they took a poke at Dayton, oh my God. He’d hit ’em with both fists and kick at a well-defined area between the head and the groin. I’ve seen people try to fall when Dayton was working on them, and they couldn’t because the rain of blows was that intense. They’d eventually go down, and Dayton would keep it up until they hit the floor. He would clean house! One night I had to stand between Dayton and a friend of mine. That was scary.

During this period we played a week at the Canadian Club in Tulsa, after which the owner gave us a check that bounced as soon as we tried to cash it. Well, that made us angry. We’d heard this guy had stiffed a lot of other musicians, including Ray Charles just a month earlier. I hated that particular place because it had a low, spackled plaster ceiling. Whenever I got up from the drums, I’d always hurt my head on the little “stalactites.” Jimmy “Pork Chop” Markham, who played drums with Conway Twitty, told me he had the same problem. All drummers hated the joint.

The Canadian Club’s owner had gotten away with ripping off musicians because he figured no one had enough money to hire a lawyer and go after him. So Ronnie, Dayton, Donny Stone, and I decided to take matters into our own hands. We went back to the club that night after closing. Leon Russell had the house band, and we tenderly moved his equipment out to the parking lot, because Leon’s gear wasn’t paid for yet. Then Hawk and Dayton went in, broke the beer machine, and generally wrecked the place. Then Ronnie poured fifteen gallons of gas on the floor, running a line of gas out the back door to the parking lot. That’s the way they did it in the movies.

Well, I lit the match, touched the line of gas, and it all blew at once! The force of the explosion knocked us all down. The Hawk was blown through the back door of the club, and his eyebrows got burned off. There was nothing left of the Canadian Club except smoking rubble. We were too dazed to leave the scene and were still there when the cops arrived.

They let us go! Told us the owner was a lowlife who was always causing trouble. “Hell, boys,” they told us, “you done us a favor. We’ll just say we couldn’t find the arsonists. Now get out of here and don’t come back.”

Later, Dayton and Donny returned, found out where the club owner lived, wrecked the Cadillac parked in front of his house, then went in and got the money he owed us. We heard this guy took out a contract on us, but we never heard from the hired killers and are still laughing about torching the Canadian Club to this day.

Instead of going straight back to Canada, we stopped in Nashville to record Ronnie’s next record, Ronnie Hawkins Sings the Songs of Hank Williams.

The two worst things a musician can say to his producer in Nashville are “I’ve been thinking” and “I’d like my band to play on the record.” Country records were all cut by a clique of studio musicians, and the artist’s wishes never entered into it. Well, we arrived at Bradley Studio, an old Quonset hut, ready to cut “Jambalaya,” “Hey, Good Lookin’,” and Hank’s other songs, and the Hawk floored ’em by demanding that we all play on the record. The producer said no, and Hawk read ’em the riot act. The Nashville session people were sitting around and didn’t like this. They looked at us, we looked at them, the Hawk was shouting, and it looked like our Nashville debut was going to end in a fistfight. Meanwhile, downstairs in studio B, Bobby “Blue” Bland and his orchestra were recording “Turn on Your Love Light.” I could hear the music leaking out of the studio; Blue Bland was a hero to me, and I was itching to go downstairs and listen.

The Hawk won eventually, and his Hank Williams LP was released in November 1960. I didn’t enjoy Nashville and got out as soon as I could, but Fred Carter, Jr., saw the light when he realized a studio guitarist could earn twenty times what a musician could earn on the road. Fred kept talking about it, and we could see his days in the band were numbered.

Sure enough, he soon carried out his plan to move to Nashville. There Fred quickly became one of the elite studio guitarists and then a record executive with his own studio.

There’s a period in here where the Hawks’ guitar players were all jumbled up. For a short time Fred was replaced by Roy Buchanan, a brilliant and moody player who definitely had his own mystique. He had a beatnik look, complete with goatee, which both Ronnie and I adopted for a while. Roy had strange eyes, didn’t talk to anyone, and looked real fierce. Ronnie always reminded us to smile, move, and dance when we played. We had to look like we were having a better time than anyone. It was show business, those little leg kicks that fellas in bands had to do back then.

Not Roy. He didn’t believe in putting on a show. He just stood there and played the shit out of that guitar. Roy played a Louisiana Hayride style like Fred and James Burton, who was playing with Ricky Nelson then. We loved how good Roy was, but he was too weird for the Hawk. One night Roy tried to convince us that he was a werewolf and destined to marry a nun. Not long after that, Robbie took over the lead guitar.

The Hawk was thinking about me playing second guitar. I wasn’t a lead guitarist, but I did play a decent rhythm guitar. “Do you know,” he asked, “how powerful two guitars could be?” I remembered Luke and Fred together just a couple of months earlier: It was a hell of a sound. Pork Chop Markham came up from Arkansas for a look but decided he was better off with Conway. We also thought about Sandy Konikoff, the drummer in Stan Szelest’s former band, but then the Hawk decided to stay with one guitar.

So we hired Rebel Paine from Buffalo to play bass. He must have come in with, or just after, Stan. Rebel was a Seminole, originally from the Florida Everglades, and a hellacious character and a great bass player. Willard was back in the group, and Stan was playing keyboards, with Robbie on guitar and me on drums.

To me, Stan was the demon in the Hawks. I was in awe of him, not only for his musical ability (which bordered on magic) but because he actually kicked the shit out of me a couple times when I got on his nerves. Stan was a big, strong rocker, and he didn’t take any shit from anyone—especially me, who liked to give it out. One time he said to me, “Levon [by then the boys had changed my name from Lavon because it was easier to say], for two cents I’d kick your ass.”

I said, “Hell, Stan, I’ll give you a goddamn dollar bill.”

The Hawk says, “OK, best man spits over my finger” (an old Arkansas way of starting a fight), and Stan and I started swinging at each other in the hotel room, knocking over lamps and breaking things. The Hawk made us finish it in the parking lot. I kneed Stan in the gut; then he punched me in the forehead. I felt stunned, like a hog staring at a wristwatch. Stan was throwing up. For the next month it was like sitting next to a rattlesnake in the Cadillac.

Robbie Robertson had a Steve Cropper rhythm-section style of playing. He was an ensemble player, like we all had to be. He had a serious side, but he was just a kid like the rest of us, so he was a good laugher and fit in pretty well. Eventually, after Stan and Rebel went back to Buffalo, Robbie and I got to be close friends.

“The one who really saved my ass was Levon,” he once recalled. “He was my best friend, my big brother. He taught me the tricks of the trade. Ronnie taught me the sexual tricks; with Levon it was the angle, the inside scoop on style and southern musical things.”

This is true, if you don’t mind my saying so. I took Robbie under my wing, and we roomed together on the road for some time afterward. It was me and Robbie against the world. Our mission, as we saw it, was to put together the best band in history.

Realigned, the Hawks took to the road.

The Hawk’s trailer was made to match his car. We had the Cadillac of trailers. It was like a little teardrop-shaped ice-cream wagon back there, but wasn’t a lot higher than the Cadillac itself, so you had to give it a little extra room, coming around people. The trailer was white, and had a hawk painted on the side. I mean, you couldn’t miss us. Years later Dr. John told me he’d seen us go by in Louisiana in the early sixties. He said we were going at a pretty good clip.

I was at the wheel. Always. The Hawk knew I’d push it up and we’d get there faster. My tractor-driving experience came in handy one night when we lost the trailer on the northeast side of Mount Gaylor, where the Ozarks peak. Late at night, I’m doing maybe eighty, eighty-five, and that damn thing hits a rock and comes loose. The safety chains had enough slack in ’em to hold the turn, about three inches off the road. “Son,” the Hawk says, while the boys are hollering in the back, “if that son of a bitch is goin’ off the cliff, we’re goin’ with it.”

To stop the thing I had to pop the brake and stab maybe twelve inches of ’59 Cadillac tail fin through the window of the trailer. It looked awful. I lived through that twice, and it scared the hell out of us.

Our first roadie was a skinny, very funny guy from Scotland who managed one of the all-day movie theaters on Yonge Street. He let us in anytime in the afternoon. His name was Colin McQueen, but the Hawk called him Bony.

He unloaded the trailer and set up our gear until he ran afoul of the Cadillac. The Hawk was strict about that car and could spot a dent from a hundred yards. One day he saw a little nick about the size of a quarter in the bumper, inches from the steel post the car was parked against. Bony had the keys because the Hawk had told him to get the car washed. So Bony had a short career with the Hawk, who was always a stern taskmaster.

For a while we had to cart our own stuff, set it up, try to clean up a little bit. Then we met Bill Avis, from Lake Simcoe, Ontario, and the Hawk hired him to be our road manager.

“I met Ronnie and the band in early 1961,” Bill remembers, “when they were playing at the Le Coq D’Or in Toronto. I’d quit school due to hard times and was hanging out, looking for work. I tried to see Ronnie when he was in town because it was simply the best band anyone had ever heard—country rock and roll. Hawk did that camel walk and people went nuts. And there’d be Levon, dead center, stage rear, twirling his drumsticks and singing ‘Slippin’ and Slidin” and ‘Short Fat Fannie.’ Robbie was already in the band, with Will Pop Jones, Rebel Paine on bass, and Stan Szelest on keyboards.

“The first thing you noticed was how good-lookin’ this band was. Clean-cut, tall young men immaculately dressed in hip suits, cuff links, good haircuts. They just looked sharp. Stan Szelest looked incredible. Ronnie called Stan ‘Lon Chaney on helium.’

“The next thing you noticed was that everyone looked up to the band. All the rounders—hoods, hookers, night people—would do anything for them. These people weren’t that nice to other musicians, who noticed this. So other bands—local guys like Larry Lee and the Leisures—copied our music, our clothes, our style. There was no question about who were the kings of the hill.

“When I got the nerve to ask Ronnie for a job, he said, ‘Son, I’ll give you fifty dollars a week and all the nookie you can eat.’ That was all I needed to hear. So I was the roadie: set up the mikes, mix the sound, do a little PR on the side. They took me to Lou Myles the tailor and got me a black mohair suit like theirs. They had a big Cadillac, and later two of ’em, and we drove those suckers a million bloody miles over the next six years.

“Like most people, I got to be friends with Levon, and we roomed together quite a bit on the road. In Toronto we lived with Mama Kosh—that’s what the band called Robbie Robertson’s mom—in her house at 193 First Avenue. We rented rooms from her when we were in town playing the Le Coq D’Or, Concord Tavern, or Friar’s Tavern. She’s a lovely lady, and she genuinely loved the band.

“Her son, meanwhile, was just coming into his own as a guitar player. Robbie was too young to legally get into most of the places we played, but he could stretch those goddamn strings, man, until you’d think they’d pop. He was a player, a showman. He’d raise that right arm over a sustained note, and the place would go ape! He’d make those strings hum.

“I was so happy to be part of this gang. The Hawks were like a permanent stag party with an entourage of the most beautiful girls in Canada. We were a hot band, and we knew we were going places, even if we weren’t quite sure where we were going or even how to get there. To us back then, the sky was the damn limit!”

Nineteen sixty one was a big transitional year for us. We started it out playing a dance Dayton Stratton was putting on in Dallas the night of the Cotton Bowl. The University of Arkansas was playing Duke University, and unfortunately the Blue Devils beat us 7-6, and the Razorbacks in town for the game felt more like getting drunk than dancing. We were playing the show with Conway’s band, which had a real good drummer, Jack Nance, who I’d looked up to ever since he’d taught me how to twirl the sticks. Nobody was in a good mood that night, least of all the Hawk, who pointed to Jack and whispered to me, “You’re gonna cut Jack’s ass tonight, cut him so damn bad he’s gonna bleed. He’s gonna want to quit when you get through with him, OK?” Because it was war with the Hawk. That’s how it was. He was known for taking no prisoners.

Ronnie’s band was pretty much in flux. Willard had been going like fire for three years and wanted a change. Rebel’s wife wanted him home after a year on the road with us. One Sunday afternoon that spring we were in the Cadillac heading toward our weekly job at Pop Ivy’s in Port Dover. “If we don’t get some new blood in the group this year,” the Hawk said, “it’s gonna be all over. But it ain’t a big problem because there’s so much goddamn talent here in Ontario, I can’t even stand it.”

I was a little more skeptical.

“What about that big kid over in Simcoe?” Ronnie suggested. “What’s his name—Danko? Nice-looking boy. He’d bring in the girls, and he plays guitar in that little group of his.”

“Yeah,” piped up Robertson from the backseat, “but he only knows four chords.”

“That’s all right son,” the Hawk joked. “You can teach him four more the way we had to teach you.”

“My family lived in rural Ontario,” Rick recalls. “I’m from Greens Corner, near Simcoe, in the southern Ontario tobacco belt. My grandfather, Joseph Danko, came from the Ukraine and bought a huge farm in Manitoba to grow wheat, long before they had tractors. My dad, Maurice Danko, was born on the farm but came to Ontario when he married my mom, whose family was there. I was born at home in 1943, the third of four brothers.

“We were a musical family, all of us. My dad played mandolin and banjo. So did Uncle Spence, who married my mom’s sister. My earliest memory is pretending to play music so I could stay up to watch those people party. Dad played country music with some older people at barn dances. Those were the first times I saw people play music, people dancing—a hundred fifty dancing in a big old barn. To this day, it’s weird for me to look at people at a concert, and they’re not dancing.

“I’m like Levon. We didn’t have electricity till I was ten years old. We listened to the Grand Ole Opry on a windup Victrola and battery radios. I had a crystal set that brought in WSM and WLAC in Nashville. I could even get Wolfman Jack coming out of Nuevo Laredo. I was a bit of a showman as a kid because I was allergic to dust. I’d get these red blotches if I worked in the garden. I’d be gasping for air! So my mother got these songbooks that came out every couple of weeks, and I learned songs on the guitar. I’d get ’em from the radio too, country songs from Nashville: Kitty Wells, Red Foley, Ernest Tubb. Uncle Spence had been in Nashville and said he knew ’em all, and that really impressed me. He took me to Toronto one summer, and we got to meet [singer-banjoist] Grandpa Jones, then in his thirties!

“I was one of those kids who was basically out of the house by the time he was ten. I was playing publicly from age twelve on. The drummer was my seventh-grade teacher, Mr. Titmouse. He had a set of drums, but no cymbals. I fired him the moment I got out of public school—the only person I ever fired in my life!”

“At fourteen I realized I could rent a hall in January, Uncle Rollie would put up posters, and two hundred people would show up because there was nothing else to do. We’d be Rick Danko and the Starliners on Friday night in St. Williams, and Rick and the Roxatones on Saturday in Walsh. In Delhi we had seventeen different ethnic clubs. This was where the tobacco farmers moved after they’d turned the farms over to their kids. We’d play the Slavic club, the Belgian club. At the fairgrounds in Delhi they had a famous guy who weighed six hundred pounds. He had a hot-dog stand. To this day Levon remembers him: Alfonso Cook. The Hawks used to stop in Delhi on the way to Port Dover. Levon’d buy a few dogs and stare at Alfonso for hours.

“I quit school at fifteen. I knew I’d be playing music, but I was a serious kid and didn’t want to be dependent if I could help it, so I apprenticed myself to a meat cutter and learned how to cut meat. Not butchering, where you go for the throat a thousand times a day, but dividing it into quarters, cuts, and so on. There was an art to it, like any craft.

“I was seventeen the first time I saw the Hawk. This was at Simcoe Arena in late 1960. Conway Twitty was headlining, with Fred Carter, Jr., on guitar, after Fred had left the Hawk. The Hawks were Levon, Rebel, Stan, and Willard. Robbie was just learning guitar. The Hawks were wearing these tight black suits, and the music was more than powerful. It was unbelievable. Ronnie was doing backflips. Will Pop was playing so hard when the Hawk danced over to the piano the buttons of his clothes were ripping open. Everyone was covered in sweat. They were irresistible. Levon would just laugh into the microphone and make the whole audience laugh. They had routines, comedic timing. Mostly, Ronnie tore the place up. I never saw anything like it. He was doing James Brown steps, only faster!

“Next spring, when the Hawk came back to Simcoe, I arranged to have my band—maybe it was Ricky and the Rhythm Notes that night—open for him. That happened maybe five times. On a rainy Sunday night in May 1961, Ronnie comes up to me after the show at Pop Ivy’s in Port Dover—I couldn’t believe this—and he rasps, ‘Son, what do we have to do for you to get in that Cadillac over there and come with us tonight?’

“They had two Cadillacs. I got in with the Hawk. Bill Avis was driving. We made two stops. At the meat cutter’s I said good-bye to my boss. ‘Don’t make any rash decisions,’ he advised. When I told him I was going to Toronto with a famous rock and roll band, he shook his head and said, ‘You’ll be back.’ Then we went home to get some clothes. I told my mom I was leaving town for a couple of weeks and parked my ’49 MG convertible in the garage because it had a few holes in it. I kissed ’em good-bye and that was it. I was on the road. Hawk was telling me that I was gonna play a little rhythm guitar, but that Rebel was coming out of the band later that summer, and I’d be playing bass after that. I’d never played either in my life! Meanwhile I noticed that Bill Avis has us cruising down Highway 3 at maybe seventy-five, and all of a sudden I saw car lights coming on fast behind us. I thought it was the Mounties. But no.

“‘Pull over, son,’ Hawk said to Bill. ‘That’s Levon—give him plenty room!’ Sure enough, in ten seconds Levon blows by us at one hundred ten, windows rolled down with bare legs sticking out. Young girls’ legs. He had a beautiful ’54 two-door: dark green on top, light green on the bottom, first year of the rock-ground windshield. Filled with young women! This was Levon on his way to Grand Bend, where the Hawks were playing next. Yaa-hooooo!!!! Away we went!

“We got to Grand Bend, where the Hawk was playing a hotel on Lake Huron. They put us up in a loft over the beer storeroom, a place where they’d put in a hallway with Sheetrock, with three bedrooms on each side. I didn’t know what to expect because these guys had terrible reputations as sex perverts—orgies, gang bangs, everything. I was just a kid from Simcoe and didn’t know anything about this life they were living, this existence.”

We put young Rick Danko in one of these rooms. The Hawk gave him a couple of greenies and told him to practice while we were playing. Between sets we sent Bill Avis to peek at him through a hole in the wall.

“How’s he doing?” Hawk asked.

“Practicing like hell and chewing his teeth,” Bill replied.

“He’s too green,” Robbie said.

Hawk looked at me. I had to be honest. “I don’t think he can cut it,” I observed wisely.

“That boy’s a hell of a musician,” the Hawk said. “Take my word for it. He’s gonna play bass when Rebel goes home.”

Eventually we let Rick out of his room, and the Hawk told him to watch the band and learn that way.

“They were basically playing Ronnie’s records,” Rick says. “‘Mary Lou,’ ‘Odessa.’ Levon would get a big slot, and he’d yell out ‘Lucille’ or ‘Short Fat Fannie.’ It wasn’t hard, but I had a lot to learn. Levon and Robbie started to work with me, teaching me about the bass and the bass feeling. I rehearsed for maybe two months off the stage before they’d let me on. Rebel stayed around, but he was taking a lot of speed, and I couldn’t pick up much from him. So I used to copy Stan Szelest’s left hand.

“Every piano player who ever worked with Ronnie asked for as many tapes from Stan as they could, to study him. He was a living fountain of rock and roll piano, a one-of-a-kind player. His presence, the way he could pound a piano, was overwhelming.

“So I tried to play what Stan was doing with his left hand. I wasn’t stealing, I was learning. One night Stan gave me a look while I was copying him. He stared at me with a super-conscious look in his eye, and—magic!—all of a sudden I got better at doubling his left hand. He had transmitted some powerful force to me. Stan could just give it to you, if he wanted to.

“By midsummer 1961, Rebel was out, and I was in. Stan and I became roommates on the road, and he let me drive his ’59 Buick convertible, the ‘Ragtop.’ He wrote his rockabilly classic ‘Ragtop’ about that car, so I was honored.

“The other thing that I both recognized and respected was the bond of friendship between Levon and Robbie. It was very strong, a brotherhood, almost a family thing. It was one of the strongest relationships that I ever felt, and the energy was so good that it was fun to be around it.”

There were a couple of other developments while we were at Grand Bend. Ronnie liked to keep the pot boiling, and still hadn’t given up on the two-guitar idea. So Roy Buchanan came back for a few days, and he and Robbie had a kind of duel. Call it a showdown.

Robbie had been playing for eighteen months and was acquiring a hell of a reputation. There just weren’t many guitar players in Ontario who worked as hard as Robbie, bending strings, screaming like Jimi Hendrix would years later. The whole band was incredibly tight because Ronnie literally worked us all the time. If we played until midnight, the Hawk would let us break for “lunch” and then rehearse us till four in the morning. Whether we were in Canada or Arkansas, it didn’t matter.

Robbie had actually learned a lot from Roy, whose technical accomplishments as a blues guitarist were without peer back then. (Once I asked him where he learned to play so good and he explained in all seriousness that he was half wolf.) But Robbie was playing with total excitement and raw teenage disturbance. That’s what it boiled down to: Roy Buchanan’s tricks and technical skills versus Robbie’s ability to really rock a good dance party. I’m told there are a lot of people in that part of Ontario who remember those nights when Robbie and Roy went at it. When it was over, Robbie still held the guitar chair in the Hawks. Roy Buchanan, a true master of the electric guitar, went his own way.

Instead of a second guitar, Ronnie hired Jerry Penfound to play horns. Jerry was from London, Ontario, and played a mean baritone saxophone. It sounded low, powerful; really what you wanted to hear under what we were playing. That horn added another dimension; now we could play “Turn on Your Love Light” and soul-type songs, a direction that the band, if not the Hawk, wanted to pursue.

We called Jerry “Ish,” short for Ish Kabibble, an old radio character. He was a funny cat who was a really good cook. He’d inherited some money, could fly a plane, wore a big blue diamond ring he liked to flash at the girls. He fit in right away, and when Willard left the band at the end of the summer, Ish stayed in. People were always coming and going.

The Hawk called Will Pop Jones “Caveman.” Sometimes he called him “Bungawa.” It meant the same thing. He was a hellacious character, the living embodiment of rockabilly. He was a big, raw-boned Arkansan; maybe 185 pounds, with not an ounce of fat. His untutored country manners and habits were so crude they revolted even the Hawk, who was usually beyond embarrassment. Willard would pile white bread, mashed potatoes, and chicken gravy in ascending layers on a big plate until the food was nine inches high and dribbling over the side. He would then take this and a couple of Cokes up to his room to eat by himself, in exile. His table manners were so bad that Ronnie didn’t like to eat with him.

Willard would show up onstage very shiny, with everything in order, but he played with such ferocious energy that after one song he’d be rumpled, then totally disheveled: sweaty jacket, shirttail out, collar open, tie and hair askew, loafers half off, exposing one green sock and one purple sock. All this and hammers sailing out of the piano. Few who saw him perform ever witnessed anything like it.

Willard was unbelievably cheap. The Hawk used to say he could squeeze a nickel so hard the buffalo would shit. On the road he’d sleep in the Cadillac unless someone let him crash on the floor of his motel room. If we were all in the car, Ronnie would say, “Willard, please don’t go to sleep; you know how awful you look when you wake up.” This was because Willard had a lazy eye; one eye looked one way, the other eye went the other way. No one back home in Marianna ever thought about getting Willard the simple operation to straighten this out, and for years the Hawk ragged on him about it until we were finally able to get him to the doctor in Toronto. Willard had the operation, came out of the hospital, and was so strong he did four or five sets with us that night, wearing a patch.

After he had his eye fixed, Willard started getting dates. We all remember one famous one that didn’t work out, when Willard met a working girl during a booking at the Concord Tavern. She took him home, and it was going along pretty smooth until the subject of money came up. The lady wanted to be paid, and Willard didn’t want to hear about it. They got to shouting at each other, and Willard noticed she had a couple of hamsters in a cage. He grabbed one hamster and said, “I’ll pinch his goddamn head off! I ain’t bullshittin’ ya, girl! I’ll pinch him right now in front of you!” Willard was about to sacrifice the hamster, when the lady relented.

We were living at the Warwick Hotel at the time. A sign outside said ENTERTAINERS WELCOME, so the clientele consisted of musicians, strippers, and hookers. That address ended a lot of dates for us before they even started; killed a lot of parties. “The Warwick? Are you crazy? Forget it!”

The day after his date, Willard went downstairs to get some breakfast over at the Wilton Restaurant: two bacon cheeseburgers and a couple of cartons of milk, please. As he was walking back to the hotel, the girl’s pimp and a buddy stepped out of an alley. Willard quickly sized up the situation. These weren’t the friendly, familiar pimps that came to hear us play, like “Russian Wally” or “Ralph the Frenchman.” These guys were there either to collect or to slap Willard around a little.

“Wait just a minute,” he said, and gently laid the paper bag containing his meal against the wall. Then he whirled around, grabbed the pimp by the arm, and smashed him face-first against the side of the brick building. Willard let go of the arm, and the pimp just… faded. He fell down the brick wall like water and lay unconscious in the street.

Willard calmly picked up his sack and disappeared into the Warwick to eat by himself.

So Willard was a terrific, funny character, and I was sad to see him leave the Hawk when we went back to Arkansas in the fall of 1961.

The Hawk kept talking about getting Garth Hudson to replace Willard. Garth played the organ and some horns for a band in Detroit, and everyone kept saying he was the best musician on our circuit. Others said that Garth would rather play Bach than rock.

Hawk had tried to hire him as early as 1959, but Garth Hudson wasn’t interested in joining us. He was a little older than us, a trained classical musician who was only playing rock and roll to make a little money in his spare time. His family was very conservative, and Garth didn’t think they would approve of him joining any rockabilly band on a permanent basis. Somehow Ronnie had talked him into coming to the Le Coq D’Or to see us. It must have been December 1960.

“Aw, I finally told Ronnie I’d look at his band,” Garth remembers. “There was Willard with his pounding left-hand technique. I’d never heard anyone amplify a piano that loud before. He was a big guy with tremendous thrust, played those wild glissandos like Jerry Lee Lewis, with incredible stamina. Stan Szelest was a close second in terms of sheer power. I thought, I can’t play this music. I don’t have the left hand these guys do.”

“Then I looked a little closer. Stan Szelest’s fingers were bleeding from pounding the keys. I looked at Willard and saw hammers actually flying out of the piano. The whole thing was too loud, too fast, too violent for me.” Six months later he came to see us a second time, and again left without joining.

We all knew that if Garth Hudson joined the band, it would put us up a notch, and we’d be unstoppable. But he said no again. So Ronnie reached down into a little Stratford, Ontario, band that he was managing (he’d sent them down to Fayetteville to play the Rockwood Club) and pulled out Willard’s replacement.

Richard Manuel was a whole show unto himself. He was hot. He was about the best singer I’d ever heard; most people said he reminded them of Ray Charles. He’d do those ballads, and the ladies would swoon. To me that became the highlight of our show.

Richard already had a small following when we met him. He was born in Stratford, Ontario, in 1944. His father, Ed, was a Chrysler mechanic, and his mom taught school. Richard sang in his church choir with his three brothers and started piano lessons when he was about nine. They ended when Richard played a note that wasn’t on the sheet music. It wasn’t a wrong note, he insisted. (Later he realized it was a different voicing of the same chord.) The piano teacher slammed the lid on his fingers because she thought he wasn’t paying attention.

But the Manuel family piano soon became a hangout where Richard and his friends would get together and rehearse. “The Beak,” as he was nicknamed because of his prominent nose, was into the blues real early—Ray Charles, Bobby Bland—which he’d pick up on WLAC’s The John R. Rhythm & Blues Show after midnight. He ordered records from Memphis and Nashville by mail, and friends remember him arriving at junior high school with fresh Jimmy Reed and Otis Rush albums under his arm.

In 1960, when he was fifteen, Richard, John Till, and Jimmy Winkler started a band called the Rebels, which soon changed to the Revols in deference to Duane Eddy and the Rebels. Soon the Rockin’ Revols were the best teenage band in Stratford. Hell, even we heard about ’em. Richard, of course, was the singer. He did teen-idol songs like “Eternal Love” and “Promise Yourself” and played a mean rhythm piano on a boogie-woogie version of Franz Liszt’s “Liebestraum” that was broadcast over CKSL in London, Ontario.

We first ran into the Revols when they were opening for the Hawks at Pop Ivy’s place in Port Dover. “See that kid playing piano?” Hawk said. “He’s got more talent than Van Cliburn.” After their show, Ronnie told the Revols they were so good they were making us nervous. Richard blushed. “Thanks, but you don’t have to worry. You guys are the kings,” he told us in reply.

Next time we saw them was at a battle of the bands in the Stratford Coliseum in 1961. The Stratatones opened, we were next as headliners, followed by the Rockin’ Revols. I remember them watching us from the wings as the Hawk went wild at the edge of the stage, working the crowd. Robbie was rumbling on guitar. Nobody else was playing that good that I knew of. The Hawk was a hell of an act to have to follow; he didn’t leave you much to work with after he had exhausted an audience.

But when the Revols came on, Richard sang Ray Charles’s “Georgia on My Mind” and brought down the house. That did it, as far as the Hawk was concerned. Rather than compete with the Revols, he hired ’em. He sent them to Dayton Stratton, who booked them into the Rockwood Club and other stops on our southern circuit. The Revols lived in a house trailer in Fayetteville, which they nearly demolished, they were so wild. One time they took the Hawk’s Cadillac to Memphis to clear up an immigration problem—none of the band’s six members was much over sixteen—and got themselves arrested at three in the morning and spent the next day in the Memphis city jail until they could prove the Cadillac wasn’t stolen.

While we were in Arkansas, Stan Szelest left the band to marry his high school sweetheart, Caroline. Ronnie had a policy of discouraging us from having steady girls. Our life-style, he insisted, was not to fall in love. Ronnie only hired good-looking guys to draw girls to the places we worked. The boys were sure to follow the girls, and we’d all have a party. But if you had a girlfriend, you’d sit with her between sets instead of mingling at the bar. Ronnie figured that if you weren’t prowling around, you weren’t doing your job.

When Stan went back to Buffalo, the Hawk called Richard and told him to come on down to Arkansas. Richard turned him down because he had a pact with Jimmy Winkler: One couldn’t leave the Revols without the other. At a band meeting, Jimmy told him, “Beak, this is your chance. You better take it.”

So Richard called back, and he was in the band. His younger brother took his place in the Revols, who drove Richard to the airport for the flight to Tulsa, where we would pick him up. They bade the Beak farewell, but not before taking out a flight-insurance policy on him—just in case.

Rick Danko remembers: “Richard’s first night was a baptism because Ronnie was real drunk, and he just pulled the curtain back, showed Richard the crowd, and told him, ‘Let it ride, son!’ Richard had never played lead piano, only rhythm piano, but he could really sing. He reminded me of Ray Charles, James Brown, and Lee Marvin! That’s what he sounded like. I knew at once that Richard and I sounded great singing together. He brought a lot of powers and strengths to the group. He brought in gospel music from his church upbringing. Plus, he loved to play and just come up with new things. It was like having a force of nature in the band.”

The piano was a rhythm instrument in the Hawks, like the drums and the bass. Solos, when they happened, were played by the guitar and the horns, and later the organ. The piano was there so the rhythm didn’t drop out. Richard fit into that slot right away. Energy piano, we call it. At the same time, he gave the Hawk a rest when it came to singing, because Richard could scream a rocker or croon a ballad and make you believe it. I’d been singing only because someone had to sing when Ronnie didn’t. Having Richard’s voice put us on a higher level musically.

Richard settled in quick. He was instantly likable and extremely funny. He liked to drink a little with the rest of us; he was seventeen when we met him, and he told us with a sheepish grin that he’d been drinking for ten years. He really missed his parents when we went out on the road. In fact, we all missed our folks. We were young and away from home, and we would spend hours sitting around hotels talking about our parents, and families, and the funny things they said and did. That loneliness was a fact of our lives, and in retrospect we know it took a toll on Richard.

We spent a good part of that fall of 1961 working in the South, breaking in Rick and Richard, who’d been hired within just a few months of each other.

Usually that time of year we’d live at the Iris Motel in Fayetteville and do the frat parties, college dances, and roadhouses in Arkansas, Oklahoma, and Texas. It was a helluva circuit back then. We played places on Oklahoma Indian reservations where we felt we wouldn’t get out alive if they didn’t like us. Other places people didn’t come to hear the band; they came to steal our gear, throw coins and lit cigarettes at us, test us a little. If we got past that, then they’d listen to us. (There was a little Indian boy who used to come see us in Tulsa back then. He’d watch Robbie very carefully from down in front of the stage. You couldn’t miss him. This was Jesse Ed Davis.)

One week we played a gangster club in Fort Worth that had been robbed and firebombed so often they didn’t bother locking it at night. We had to take turns strapping on guns and guarding our equipment when the joint closed. One morning at dawn the cops burst in with dogs, and there was almost a showdown before we got it sorted out. The next night the club was teargassed by a bounced customer. These kinds of places often didn’t pay us at the end of the week, and we’d find ourselves stealing steaks from supermarkets to survive.

Just being a professional musician in that part of the country was like being a gunfighter. The younger ones wanted your reputation, and if we were a new band in town we made our last set an open session, or else. People down there all knew music, and the local guitars would come up with a smile, plug into your amp, and try to run you off the stage. They’d happily make you look like a chump, if they could.

But eventually we got that respect we were after. Despite our unsavory rep throughout the Midwest and Canada as pill-poppin’, whorevisitin’, gas-siphonin’, girlfriend-stealin’ reprobate musicians, we’d hear our competition—good bands, too—and they’d be playing our arrangements, our turnarounds, stuff we invented. That’s how we knew we were so good.

I had been bothering Ronnie for months about trying to hire Garth Hudson again. We’d seen him play with his band and in little jazz clubs, and he was a phenomenon to us because of the scope of his musical knowledge. He was as interested in good polka music as he was in J. S. Bach. He could play with Miles Davis or the Chicago Symphony or the Grand Ole Opry. We felt we had to have Garth.

When we got back to Canada the Hawk agreed we needed Garth in the band at any cost. “This guy’s a damn genius or I’m Jack Kennedy,” Hawk fumed. “I don’t even understand what he’s doing musically, but I know it works. You don’t have a great band unless you have him or someone like him, someone who’s been to school, knows how to arrange. You need him to teach the other guys.”

“Why don’t you just pay him what he’s asking,” I suggested. “How much could it be?”

“Son, Garth doesn’t just wanna get paid to play. He wants me to buy his time when he ain’t playing,” Ronnie explained. “I told him he could have anything he wanted. I told him he could give you guys music lessons when we ain’t onstage.”

“What did he say?”

“He thought it was funny. He said he would think about it if we’d throw in a new Lowrey organ as part of the bargain.”

Garth grew up in London, Ontario. “My dad, Fred James Hudson, and my two uncles were farm people from around London,” he recalls. “Not tobacco farmers. They told jokes about tobacco farmers and complained about their methods—no crop rotation, and they bleached their soil with chemical fertilizers. But Dad left the farm and went to work for the Canadian Department of Agriculture as an inspector. My mother, Olive Louella Pentland Hudson, had me in 1937, and I was her only child. I was raised in the Anglican Church, Diocese of Huron. There was a strong English tradition in the farming community, and London had some magnificent stone mansions, built with English money. I dated a girl who lived in the gardener’s house attached to one of these estates. I took her to a dance and hit a stop sign at a T intersection with a ’49 Pontiac Tierback Straight Eight. That was a dark day. I couldn’t sleep that night. In the morning I heard my folks in the kitchen. My father hadn’t seen the bumper yet. That’s when my heart problems started. I was probably sixteen.

“My mother played the accordion. She had a good ear and played the piano too. We had a player piano in the house when I was little. I guess I learned something from watching it, because I could play ‘Yankee Doodle’ by ear before taking lessons from Miss Milligan on Richmond Street. I think I was five years old. Her brother played first violin with the Hart House Symphony, an old Toronto institution. My first record—I still have it—was a 78 with a chip in it: ‘Wild Old Horsey’ with ‘Gee It’s Great to Be Living Again’ on the other side. It was kind of country swing put out by a political-religious movement of the late 1940s called MRA: Moral Rearmament of America.

“My dad played flute, drums, cornet, saxophone, and triangle. Dad had a C-melody silver saxophone. He’d get it out every year or so, put a handkerchief in it, and play sweet band music like the Lombardos, Guy and Carmen, who were from nearby London. They had the Royal Canadians. All my uncles played too, and they were good musicians. My uncle Austin played trombone. He had great tone and worked at the London Arena four or five nights a week with various bands. Sometimes they played the Stork Club in Port Stanley, thirty miles south of London on the shore of Lake Erie. It had the largest ballroom floor in Canada. Later I played there myself with dance bands.

“I sort of grew up with country music because my father would find all the hoedown stations on the radio, and then I played accordion with a little country group when I was twelve. My parents sent me to study piano at the Toronto Conservatory. I had a good teacher who used older methods and older pieces. That’s how I learned to play the Bach preludes and fugues, material like that. I loved Chopin, and Mozart amazed me. But I found I had problems memorizing classical annotated music. I could do it, but not to the extent that is necessary. So I developed my own method of ear training and realized I could improvise.

“Another uncle of mine owned a funeral home. That was where I started playing in public. They had a good organ, and I played hymns from the Anglican Church, but usually it was Baptist hymns: ‘What a Friend We Have in Jesus,’ ‘Jesus, Keep Me Near the Cross.’ When we played ‘Abide With Me,’ that was the signal for the minister to come in.

“I had a high-school guidance counselor who laughed when I told him I might like to be a professional musician. He told me music was a hobby, and I ought to think about going into agricultural research, which is what I thought I was going to do. But I also had a teacher who played in a big band, who saw I was interested in transcribing music. He asked me to do something for him, and I used a record player and wrote down what I heard. Then he played the transcriptions with his band.

“My first group was the Three Blisters, and we backed up the highschool variety shows and the choirs. Then we had the Four Quarters. I played the accordion, still one of my favorite instruments. Then—either 1952 or 1953—I started to tune into Alan Freed’s Moondog Matinee from Cleveland, from 5:05 to 5:55 every day. He played great rhythm and blues, and I remember him talking about the first Moondog Coronation Ball, where they had thousands of people who couldn’t get in. It was almost a riot. That’s when I realized there were people over there having more fun than I was.

“There was a little rockabilly band in London called the Melodines. They did Bill Haley stuff, pretty well too. So some friends and I formed a group called the Silhouettes. We played around town and then went to the Windsor-Detroit area, where there was more opportunity to work. We hooked up with a young singer and called ourselves Paul London and the Kapers. I guess my professional career began at Aybar’s Island View Tavern in Windsor, Ontario, with Paul London.

“We played teen hops and similar things. I originally wanted to play piano in the band, but it turned out to be more fun to play the saxophone. Our repertoire was Little Richard and Larry Williams. We did ‘Long Tall Sally,’ ‘Hoochie Koo,’ and ‘Ready Teddy.’ I think I moved to piano when we played an afternoon dance party on CFPL-TV. To learn what to play, I listened real close to Johnnie Johnson, Chuck Berry’s piano player. I wanted to play organ, but I couldn’t afford the one I wanted. Other bands in Detroit used organ, but one group had a Lowrey, and it sounded great. I went to a music store and tried one out, and the Lowrey had certain things a Hammond couldn’t do.

“One night we all went to the Brass Rail in London to see the Hawk at a dinner show. Everyone I knew thought that Ronnie was the best rockabilly performer with by far the best band. Nobody could follow the Hawks, including Elvis, as far as being an organic unit that could get up there and shake it up! He was great and funny. To begin the set Ronnie’d yell, ‘It’s orgy time!’ and that would get everyone laughing and in the spirit of the thing. I remember we were nervous because we were mostly underage, but we got in. Boy, the Kapers were impressed by the power and speed of the thing. The Hawk was billed as ‘Mr. Dynamo’ and more than lived up to the label. They had Willard Pop Jones, with that left hand going all the time. He was breaking the keys! That’s where I met Levon and Robbie for the first time.

“Then we saw the Hawks again, at the Legion Hall in Ingersoll, Ontario. They played ‘Mary Lou’ and Ronnie’s other hits, and I recall a Marty Robbins-style song called ‘Hayride’ that would rear its ugly head. I think that was when they invited me into the band, after Hawk sent Levon and Robbie over to check me out. I met with Robbie in Grand Bend, and we talked about it, but I told them no. I wasn’t interested in that kind of music at the time. I liked chord changes and music that was a little more ‘uptown.’ Our band was playing rockabilly, but I didn’t have the left hand for that pounding technique that Willard and Stan Szelest used. My family also thought ‘rock and roll musician’ was a déclassé occupation, especially after my conservatory background, and they were already upset with me for dropping out of college after only a year. So I decided to stay local with Paul London and the Kapers.

“Later in 1961, Willard left the band because he couldn’t stand the pace. He went home and got married. Then Rebel Paine and Stan Szelest left, and Ronnie kept trying to get me into the band. The Kapers had made a couple of records in Detroit—‘Sugar Baby’ and ‘Big Bad Twist’—and we were promoting them (one went to No. 8 on the local chart), but we couldn’t get it on American Bandstand, we were told, because of two negative words. That was the way it worked.

“I saw the Hawks were making the big money because they worked seven nights a week, every week. I told my parents about Ronnie’s offer to join the band, but they still disapproved of my playing music in bars and taverns. Finally I had Ronnie talk them into it.

“‘Mr. and Mrs. Hudson,’ Ronnie told them in his most earnest and straightforward manner, ‘I have a band of talented young men who are being held back by their lack of musical education. I want to hire your son Garth to come along and teach them music. I want them to learn how to read notation properly. I’ve offered Garth a higher wage than anyone else, a cash bonus to join us, and we will pay him an extra ten dollars a week for the lessons he gives the boys. We’ll also buy a new organ so Garth can be heard at his best. Now, how about it? Do we have your blessing on this?’

“My parents, God bless them, finally said it was OK. This was in late 1961, around Christmastime. It was Levon, Robbie, Rick, Richard, and Garth for the first time.

“That’s when I went to organ. Richard not only had the voice, he had this great rhythmic feel, so I never had to play that heavy left-hand stuff. We bought a Lowrey organ, which nobody else was using except that guy in Detroit. I played it for the next fifteen years.”

I understood the qualms Garth’s family had. We all did, because back then being a professional musician wasn’t something you’d brag about. It wasn’t something your girlfriend could go tell everybody. Actually, it was a strike against you. I was almost twenty-two years old and making pretty good money, but I could barely get car insurance. They’d cancel you if they found out you were a musician. We were on their back page, along with athletes, jockeys, and race-car drivers.

With Garth and that organ, we sounded like a rock and roll orchestra. We felt so enriched it was ungodly. He had sounds no one else had. He liked that pedal-steel-guitar stop on the Lowrey; it sounded like a fire-breathing dragon. He had a horn like a car horn hooked to the top of his Leslie speaker cabinet. He’d hit a frequency that sounded that horn, and it was wild.

Garth was a serious musician. He spoke slowly and deliberately, and whored around less than us. Just having Garth as a teacher was an honor. He’d listen to a song on the radio in the Cadillac and tell us the chords as it went along. Complicated chord structures? No problem. Garth would figure them out, and we found ourselves able to play anything. Our horizons were lifted, and the thing became more fun. It was like we didn’t have to guess anymore, because we had a master among us. That’s how it felt.

Garth also brought a second saxophone to the band. With Jerry Penfound’s baritone and Garth’s alto, we had a soul-band horn section when we needed one. That really changed our sound toward a more R&B feel from the rockabilly we’d been playing for almost four years.

The main thing was, we were back to that double keyboard, Richard and Garth. That’s what we built on until we really thought we were the best band in the world.

Nineteen sixty-two was the first full year of the new band. It was also the year that everything began to change for us, especially when the Hawk got married.

Up till then, we were laughing all the time. Ronnie made sure that we had the worst reputation in North America. Richard always had a lot of girlfriends. He even chased girls that I was dating. If Robbie or Rick had a pretty girl, Richard might go after her too. “Son,” the Hawk used to say, laughing with paternal pride, “that Richard is a damn home wrecker!”

“This was a good-looking group,” Bill Avis recalls. “When we came into a room, people looked. The women stared. We did everything with class, and there was nothing to worry about but a case of the clap and maybe the crabs. It was a much different era.”

Yet I also can’t help but remember all the nights there weren’t wild parties, when we’d rehearse until dawn and then worry about where we wanted to go and how we were gonna get there. All those nights when Ronnie yelled, “It’s orgy time!” and Garth and I would wink at each other and try to stay focused on what we could do with the band if we had the chance.

No one loved women more than the Hawk. You’d walk into Ronnie’s suite at the Frontenac Arms Hotel, where we were living by then, and there’d be girls on every couch, every chair, waiting to get into his room, where he’d be holding court in bed. But the Hawk’s attitude changed after he met gorgeous Wanda Nugurski, who showed up one day on the “Coke side” of the Concord Tavern in Toronto. That was the nonalcoholic part of the Concord, where all the young musicians would come to watch us and learn. The Hawk was really smitten with Wanda (“Dammit, Levon, she’s the only woman in the world who’s got a dildo with two gears!”) and married her on March 15, 1962. I had the honor of serving as best man. Ronnie had nominally fought the marriage all the way down the aisle, but he was twenty-seven years old and wanted to have a family. Actually, he wanted it all: the family and the life-style of the rock and roll star. Damn if the Hawk didn’t have it all, at least for a while.

If Friday nights were hot for us, then Sundays were our downtime. We’d sleep late, play casino, drink Red Cap beer, and watch television. It was the only time in our lives things were quiet and we weren’t moving. Soon it seemed like Ronnie was more interested in Sundays than in Fridays, especially after Ronnie, Jr., was born a year after the wedding. That’s when things began to change.

Of course, we were on the road a lot that year; one of the last of the old-time rock and roll bands. We played the middle of North America in a vertical arc from Molasses, Texas, to Timmins, Ontario—so far north it was only a couple of hours from the arctic tundra. We logged thousands of miles in Ronnie’s ’62 Cadillac, all of us crammed in there. One night the Hawk was sleeping, and Richard stubbed out a cigarette on Ronnie’s hand, which must have been resting on the ashtray. Oh God, the Hawk was mad! He didn’t smoke himself, and it was always an issue among the band. There might be some ash on the carpet, and he’d say, “See that, son?” He thought it was a nasty habit, and he said he was scared for us. Eventually the Hawk offered us a hundred dollars each if we’d quit, and the boys took him up on it. So when it was cigarette time, I’d eat one of those little boxes of raisins—six for a nickel. I’d pass some to my buddies in the backseat. Next thing you know, someone had dropped a raisin in the back of the car, so the sun would hit it just right. When we were unloading or going into a restaurant, the raisin got stepped on and smeared like a flapjack. The Hawk was displeased when he saw that. “Goddamn,” he growled, “I gave you guys a hundred to get off cigarettes. I’ll give you two hundred to get rid of these damn raisins!”

It was around this time that Robbie and I bought our own Cadillac. Everyone in the band treated it like it was their car, and it was trashed in eight months. I think we got a Volkwagen bus after that.

As usual, we went home that spring to play our southern circuit.

Lavon Helm, age thirteen, hamboning at a 4-H Club talent show in Phillips County, Arkansas, circa 1953 (TURKEY SCRATCH ARCHIVES)

Thurlow Brown, Linda Helm, and Lavon Helm at a show at Marvell High School, circa 1955 (COURTESY C. W. GATLIN)

Sonny Boy Williamson and His King Biscuit Entertainers at radio station KFFA, Helena, Arkansas, circa 1943 (COURTESY KFFA/DELTA CULTURAL CENTER)

Conway Twitty (second from left) and the Rock Housers, circa 1956 (MICHAEL OCHS ARCHIVES)

Ronnie Hawkins and the Hawks when they arrived in New York in 1958. From left: Levon Helm, Ronnie Hawkins, Jimmy Ray “Luke” Paulman, and Will “Pop” Jones. (MICHAEL OCHS ARCHIVES)

Ronnie Hawkins and the Hawks, circa 1960. From left: Stan Szelest, Rebel Paine, Ronnie, Robbie Robertson, and Levon Helm. Kneeling in front is band mascot, Freddie McNulty. (COURTESY RICHARD BELL)

Ronnie Hawkins and the Hawks at the Brass Rail in Hamilton, Ontario, circa 1963. From left: Rick Danko on bass, Richard Manuel on piano, Ronnie (note the beatnik goatee), Levon on drums, Robbie Robertson on guitar, and Garth Hudson on Lowrey organ. (TURKEY SCRATCH ARCHIVES)

Levon and the Hawks in New York, 1964. From left: Jerry “Ish” Penfound (who played saxophone), Rick Danko, Levon, Richard Manuel, Garth Hudson, and Robbie Robertson. (TURKEY SCRATCH ARCHIVES)

Levon and the Hawks were headlining Tony Mart’s big nightclub in Somers Point, New Jersey, in August 1965 when they were “discovered” by Bob Dylan. (TURKEY SCRATCH ARCHIVES)

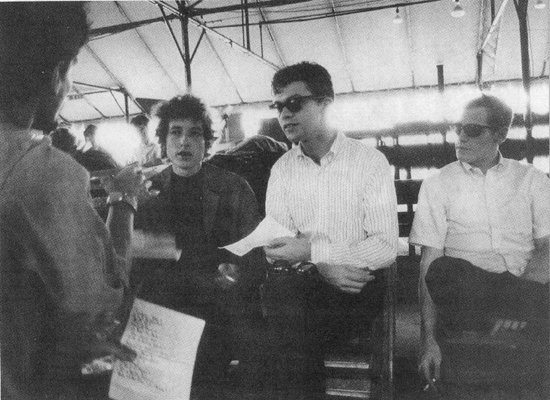

Bob Dylan, Robbie, and Levon go over Bob’s song lyrics backstage at Forest Hills, New York, on August 28, 1965. (PHOTO © 1967 DANIEL KRAMER)

Bob Dylan, Harvey Brooks, Robbie, and Levon onstage at Forest Hills, August 28, 1965 (PHOTO © 1967 DANIEL KRAMER)

Clockwise from top: Garth, Levon, and Richard playing football at Big Pink, Woodstock, New York, spring 1968 (ELLIOTT LANDY)

Just as photographer Elliott Landy was shooting The Band for the Music from Big Pink album sleeve, a friend of ours took off her clothes in an attempt to get us to lighten up. (ELLIOTT LANDY)

The Big Pink group photo was taken at a house Levon and Rick were renting at nearby Wittenburg, New York, spring 1968. Our dog Hamlet, a gift from Bob Dylan, was present at the creation. (ELLIOTT LANDY)

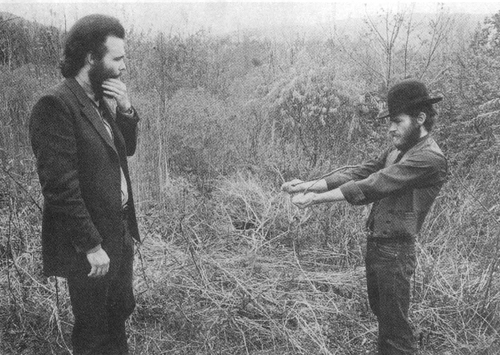

Garth Hudson instructs Levon in the finer points of dowsing, spring 1968. (ELLIOTT LANDY)

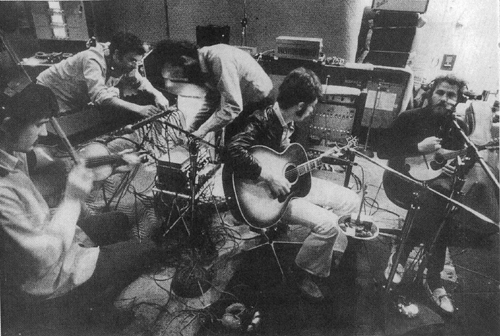

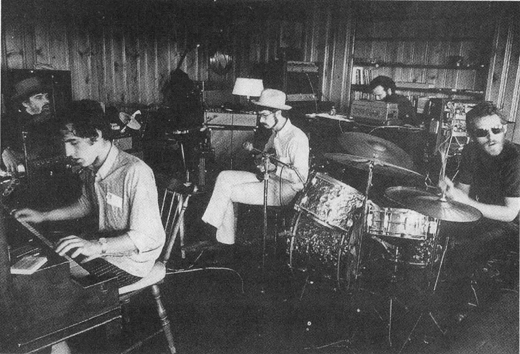

Recording “Rag Mama Rag” in California, winter 1969. Producer John Simon leans over keyboard at left. (ELLIOTT LANDY)

The Band posing for the brown album in Rick’s basement, early 1969 (ELLIOTT LANDY)

Band rehearsal at the house shared by Garth and Richard on Glenford Road, 1969 (ELLIOTT LANDY)

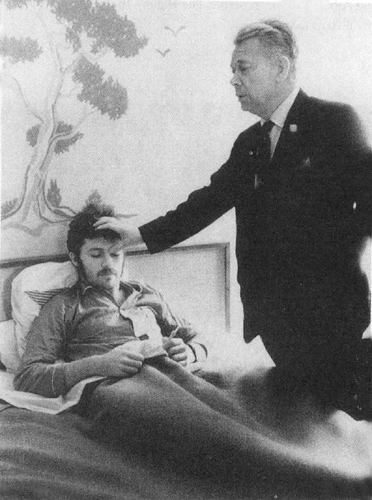

Robbie Robertson and the hypnotist, San Francisco, April 1969 (ELLIOTT LANDY)

Robbie, Levon, John Simon, Rick, and Albert Grossman before The Band’s first show at Winterland, San Francisco, April 1969 (ELLIOTT LANDY)

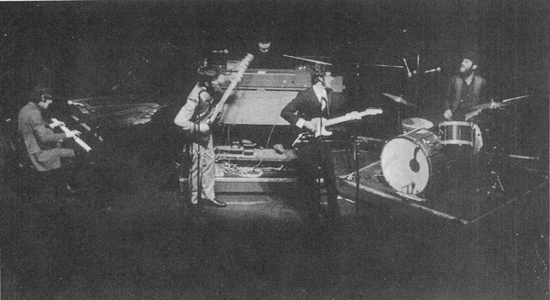

The Band at the Fillmore East, New York City, May 1969 (ELLIOTT LANDY)

Ronnie had his club and his farms in the Fayetteville area, and I bought a house for my folks in nearby Springdale. Friends of ours were putting in a development, interest rates were around 4 percent, and they lent me the down payment as well. My dad had stopped farming by then, and the family was ready for a move out of cotton country. I continued to send a little money home every payday—the band was making maybe $2,500 a week by then—and it was a better situation because the family could be together when the Hawks came down to touch home base every few months.

Tension filled the air that summer and fall of 1962 because of the Cuban missile crisis. President John F. Kennedy found out that the Russians were building missile sites in Fidel Castro’s Cuba, a mere ninety miles from Florida. In October he went on television to announce he’d given Premier Nikita Khrushchev an ultimatum: Get the missiles out or else face an American blockade of Russian shipping to Cuba. “Naval blockade’s an act of war,” Ronnie mused one evening while waiting to go onstage. The Strategic Air Command was put on red alert. B-52s were flying overhead, and things seemed pretty apocalyptic. People were nervous. We’d all grown up with those air-raid drills in school, hadn’t we?

We were in London, Ontario. “It looks bad, son,” the Hawk opined. “It could get into World War III.” I got pretty scared. If North America was going to be incinerated by nuclear bombs, I decided I didn’t want to die in Canada. I got a road map, and the Hawk and I planned our route in case of war. We could leave London, go through Sarnia, and head down through central Michigan. I wasn’t about to drive through Detroit. We figured we could get to Arkansas without hitting any major city on the Soviets’ target list.

October 27 was the deadline Kennedy had given the Russians to pull out. That night we were playing the Brass Rail, and everyone was a little tense. Even Freddie McNulty was subdued. There was a feeling of the impending end of civilization. We were right in the middle of a tune when the Hawk got onstage and killed the music with a wave of his hand.