The 1999 Arden text is based on the 1623 First Folio.

MIRANDA If by your art, my dearest father, you have |

|

Put the wild waters in this roar, allay them. |

|

The sky, it seems, would pour down stinking pitch |

|

But that the sea, mounting to th’ welkin’s cheek, |

|

Dashes the fire out. O, I have suffered |

5 |

With those that I saw suffer – a brave vessel |

|

(Who had no doubt some noble creature in her) |

|

Dashed all to pieces. O, the cry did knock |

|

Against my very heart! Poor souls, they perished. |

|

Had I been any god of power, I would |

10 |

Have sunk the sea within the earth or ere |

|

It should the good ship so have swallowed and |

|

The fraughting souls within her. |

|

PROSPERO Be collected; |

|

No more amazement. Tell your piteous heart |

|

There’s no harm done. |

|

MIRANDA O woe the day. |

|

PROSPERO No harm! |

15 |

I have done nothing but in care of thee, |

|

Of thee, my dear one, thee my daughter, who |

|

Art ignorant of what thou art, naught knowing |

|

Of whence I am, nor that I am more better |

|

Than Prospero, master of a full poor cell, |

20 |

And thy no greater father. |

|

MIRANDA More to know |

|

Did never meddle with my thoughts. |

|

PROSPERO ’Tis time |

|

I should inform thee further. Lend thy hand |

|

And pluck my magic garment from me. So, |

|

Lie there my art. Wipe thou thine eyes, have comfort; |

25 |

The direful spectacle of the wreck which touched |

|

The very virtue of compassion in thee, |

|

I have with such provision in mine art |

|

So safely ordered, that there is no soul – |

|

No, not so much perdition as an hair, |

30 |

Betid to any creature in the vessel |

|

Which thou heard’st cry, which thou sawst sink. |

|

Sit down, |

|

For thou must now know further. |

|

MIRANDA You have often |

|

Begun to tell me what I am, but stopped |

|

And left me to a bootless inquisition, |

35 |

Concluding, ‘Stay, not yet’. |

|

PROSPERO The hour’s now come; |

|

The very minute bids thee ope thine ear. |

|

Obey and be attentive. Canst thou remember |

|

A time before we came unto this cell? |

|

I do not think thou canst, for then thou wast not |

40 |

Out three years old. |

|

MIRANDA Certainly, sir, I can. |

|

PROSPERO By what? By any other house or person? |

|

Of any thing the image, tell me, that |

|

Hath kept with thy remembrance. |

|

MIRANDA ’Tis far off, |

|

And rather like a dream than an assurance |

45 |

That my remembrance warrants. Had I not |

|

Four or five women once, that tended me? |

|

PROSPERO |

|

Thou hadst, and more, Miranda. But how is it |

|

That this lives in thy mind? What seest thou else |

|

In the dark backward and abysm of time? |

50 |

If thou rememb’rest aught ere thou cam’st here, |

|

How thou cam’st here thou mayst. |

|

MIRANDA But that I do not. |

|

PROSPERO Twelve year since, Miranda, twelve year since, |

|

Thy father was the Duke of Milan and |

|

A prince of power. |

|

MIRANDA Sir, are not you my father? |

55 |

PROSPERO Thy mother was a piece of virtue, and |

|

She said thou wast my daughter; and thy father |

|

Was Duke of Milan, and his only heir |

|

And princess, no worse issued. |

|

MIRANDA O, the heavens! |

|

What foul play had we that we came from thence? |

60 |

Or blessed wast we did? |

|

PROSPERO Both, both, my girl. |

|

By foul play, as thou sayst, were we heaved thence, |

|

But blessedly holp hither. |

|

MIRANDA O, my heart bleeds |

|

To think o’th’ teen that I have turned you to, |

|

Which is from my remembrance. Please you, farther. |

65 |

PROSPERO My brother and thy uncle, called Antonio – |

|

I pray thee mark me, that a brother should |

|

Be so perfidious – he, whom next thyself |

|

Of all the world I loved, and to him put |

|

The manage of my state, as at that time |

70 |

Through all the signories it was the first, |

|

And Prospero the prime Duke, being so reputed |

|

In dignity, and for the liberal arts |

|

Without a parallel; those being all my study, |

|

The government I cast upon my brother |

75 |

And to my state grew stranger, being transported |

|

And rapt in secret studies. Thy false uncle – |

|

Dost thou attend me? |

|

MIRANDA Sir, most heedfully. |

|

PROSPERO Being once perfected how to grant suits, |

|

How to deny them, who t’advance and who |

80 |

To trash for overtopping, new created |

|

The creatures that were mine, I say, or changed ’em, |

|

Or else new formed ’em; having both the key |

|

Of officer and office, set all hearts i’th’ state |

|

To what tune pleased his ear, that now he was |

85 |

The ivy which had hid my princely trunk |

|

And sucked my verdure out on’t. Thou attend’st not! |

|

MIRANDA O, good sir, I do. |

|

PROSPERO I pray thee, mark me. |

|

I thus neglecting worldly ends, all dedicated |

|

To closeness and the bettering of my mind |

90 |

With that which, but by being so retired, |

|

O’er-prized all popular rate, in my false brother |

|

Awaked an evil nature, and my trust, |

|

Like a good parent, did beget of him |

|

A falsehood in its contrary as great |

95 |

As my trust was, which had indeed no limit, |

|

A confidence sans bound. He being thus lorded, |

|

Not only with what my revenue yielded |

|

But what my power might else exact, like one |

|

Who, having into truth by telling of it, |

100 |

Made such a sinner of his memory |

|

To credit his own lie, he did believe |

|

He was indeed the duke, out o’th’ substitution |

|

And executing th’outward face of royalty |

|

With all prerogative. Hence his ambition growing – |

105 |

Dost thou hear? |

|

MIRANDA Your tale, sir, would cure deafness. |

|

PROSPERO |

|

To have no screen between this part he played |

|

And him he played it for, he needs will be |

|

Absolute Milan. Me, poor man, my library |

|

Was dukedom large enough. Of temporal royalties |

110 |

He thinks me now incapable; confederates, |

|

So dry he was for sway, wi’th’ King of Naples |

|

To give him annual tribute, do him homage, |

|

Subject his coronet to his crown, and bend |

|

The dukedom yet unbowed (alas, poor Milan) |

115 |

To most ignoble stooping. |

|

MIRANDA O, the heavens! |

|

PROSPERO |

|

Mark his condition and th’event, then tell me |

|

If this might be a brother. |

|

MIRANDA I should sin |

|

To think but nobly of my grandmother; |

|

Good wombs have borne bad sons. |

|

PROSPERO Now the condition. |

120 |

This King of Naples, being an enemy |

|

To me inveterate, hearkens my brother’s suit, |

|

Which was that he, in lieu o’th’ premises |

|

Of homage, and I know not how much tribute, |

|

Should presently extirpate me and mine |

125 |

Out of the dukedom and confer fair Milan, |

|

With all the honours, on my brother. Whereon – |

|

A treacherous army levied – one midnight |

|

Fated to th’ purpose did Antonio open |

|

The gates of Milan and i’th’ dead of darkness |

130 |

The ministers for th’ purpose hurried thence |

|

Me and thy crying self. |

|

MIRANDA Alack, for pity. |

|

I, not rememb’ring how I cried out then, |

|

Will cry it o’er again. It is a hint |

|

That wrings mine eyes to’t. |

|

PROSPERO Hear a little further, |

135 |

And then I’ll bring thee to the present business |

|

Which now’s upon’s, without the which this story |

|

Were most impertinent. |

|

MIRANDA Wherefore did they not |

|

That hour destroy us? |

|

PROSPERO Well demanded, wench: |

|

My tale provokes that question. Dear, they durst not, |

140 |

So dear the love my people bore me, nor set |

|

A mark so bloody on the business, but |

|

With colours fairer painted their foul ends. |

|

In few, they hurried us aboard a bark, |

|

Bore us some leagues to sea, where they prepared |

145 |

A rotten carcass of a butt, not rigged, |

|

Nor tackle, sail, nor mast – the very rats |

|

Instinctively have quit it. There they hoist us |

|

To cry to th’ sea that roared to us, to sigh |

|

To th’ winds, whose pity, sighing back again, |

150 |

Did us but loving wrong. |

|

MIRANDA Alack, what trouble |

|

Was I then to you? |

|

PROSPERO O, a cherubin |

|

Thou wast that did preserve me. Thou didst smile, |

|

Infused with a fortitude from heaven, |

|

When I have decked the sea with drops full salt, |

155 |

Under my burden groaned, which raised in me |

|

An undergoing stomach to bear up |

|

Against what should ensue. |

|

MIRANDA How came we ashore? |

|

PROSPERO By providence divine. |

|

Some food we had, and some fresh water, that |

160 |

A noble Neapolitan, Gonzalo, |

|

Out of his charity – who, being then appointed |

|

Master of this design – did give us, with |

|

Rich garments, linens, stuffs and necessaries, |

|

Which since have steaded much; so of his gentleness, |

165 |

Knowing I loved my books, he furnished me |

|

From mine own library with volumes that |

|

I prize above my dukedom. |

|

MIRANDA Would I might |

|

But ever see that man! |

|

PROSPERO Now I arise. |

|

Sit still and hear the last of our sea-sorrow. |

170 |

Here in this island we arrived, and here |

|

Have I, thy schoolmaster, made thee more profit |

|

Than other princes can that have more time |

|

For vainer hours, and tutors not so careful. |

|

MIRANDA |

|

Heavens thank you for’t. And now I pray you, sir, |

175 |

For still ’tis beating in my mind, your reason |

|

For raising this sea-storm? |

|

PROSPERO Know thus far forth: |

|

By accident most strange, bountiful fortune |

|

(Now, my dear lady) hath mine enemies |

|

Brought to this shore; and by my prescience |

180 |

I find my zenith doth depend upon |

|

A most auspicious star, whose influence |

|

If now I court not, but omit, my fortunes |

|

Will ever after droop. Here cease more questions. |

|

Thou art inclined to sleep; ’tis a good dullness, |

185 |

And give it way. I know thou canst not choose. |

|

[to Ariel] Come away, servant, come; I am ready now. |

|

Approach, my Ariel. Come. |

|

Enter ARIEL. |

|

ARIEL All hail, great master; grave sir, hail! I come |

|

To answer thy best pleasure, be’t to fly, |

190 |

To swim, to dive into the fire, to ride |

|

On the curled clouds. To thy strong bidding, task |

|

Ariel and all his quality. |

|

PROSPERO Hast thou, spirit, |

|

Performed to point the tempest that I bade thee? |

|

ARIEL To every article. |

195 |

I boarded the King’s ship: now on the beak, |

|

Now in the waist, the deck, in every cabin |

|

I flamed amazement. Sometime I’d divide |

|

And burn in many places – on the topmast, |

|

The yards and bowsprit would I flame distinctly, |

200 |

Then meet and join. Jove’s lightning, the precursors |

|

O’th’ dreadful thunderclaps, more momentary |

|

And sight-outrunning were not; the fire and cracks |

|

Of sulphurous roaring, the most mighty Neptune |

|

Seem to besiege and make his bold waves tremble, |

205 |

Yea, his dread trident shake. |

|

PROSPERO My brave spirit, |

|

Who was so firm, so constant, that this coil |

|

Would not infect his reason? |

|

ARIEL Not a soul |

|

But felt a fever of the mad and played |

|

Some tricks of desperation. All but mariners |

210 |

Plunged in the foaming brine and quit the vessel; |

|

Then all afire with me, the King’s son Ferdinand, |

|

With hair up-staring (then like reeds, not hair), |

|

Was the first man that leapt, cried ‘Hell is empty, |

|

And all the devils are here’. |

|

PROSPERO Why, that’s my spirit! |

215 |

But was not this nigh shore? |

|

ARIEL Close by, my master. |

|

PROSPERO But are they, Ariel, safe? |

|

ARIEL Not a hair perished; |

|

On their sustaining garments not a blemish, |

|

But fresher than before; and, as thou bad’st me, |

|

In troops I have dispersed them ’bout the isle. |

220 |

The King’s son have I landed by himself, |

|

Whom I left cooling of the air with sighs, |

|

In an odd angle of the isle, and sitting, |

|

His arms in this sad knot. |

|

PROSPERO Of the King’s ship, |

|

The mariners, say how thou hast disposed, |

225 |

And all the rest o’th’ fleet? |

|

ARIEL Safely in harbour |

|

Is the King’s ship, in the deep nook where once |

|

Thou called’st me up at midnight to fetch dew |

|

From the still-vexed Bermudas; there she’s hid, |

|

The mariners all under hatches stowed, |

230 |

Who, with a charm joined to their suffered labour, |

|

I have left asleep. And for the rest o’th’ fleet, |

|

Which I dispersed, they all have met again, |

|

And are upon the Mediterranean float, |

|

Bound sadly home for Naples, |

235 |

Supposing that they saw the King’s ship wrecked |

|

And his great person perish. |

|

PROSPERO Ariel, thy charge |

|

Exactly is performed; but there’s more work. |

|

What is the time o’th’ day? |

|

ARIEL Past the mid-season. |

|

PROSPERO |

|

At least two glasses. The time ’twixt six and now |

240 |

Must by us both be spent most preciously. |

|

ARIEL |

|

Is there more toil? Since thou dost give me pains, |

|

Let me remember thee what thou hast promised, |

|

Which is not yet performed me. |

|

PROSPERO How now? Moody? |

|

What is’t thou canst demand? |

|

ARIEL My liberty. |

245 |

PROSPERO Before the time be out? No more! |

|

ARIEL I prithee |

|

Remember I have done thee worthy service, |

|

Told thee no lies, made thee no mistakings, served |

|

Without or grudge or grumblings. Thou did promise |

|

To bate me a full year. |

|

PROSPERO Dost thou forget |

250 |

From what a torment I did free thee? |

|

ARIEL No. |

|

PROSPERO |

|

Thou dost, and think’st it much to tread the ooze |

|

Of the salt deep, |

|

To run upon the sharp wind of the north, |

|

To do me business in the veins o’th’ earth |

255 |

When it is baked with frost. |

|

ARIEL I do not, sir. |

|

PROSPERO |

|

Thou liest, malignant thing; hast thou forgot |

|

The foul witch Sycorax, who with age and envy |

|

Was grown into a hoop? Hast thou forgot her? |

|

ARIEL No, sir. |

|

PROSPERO Thou hast! Where was she born? Speak; tell |

|

me. |

260 |

ARIEL Sir, in Algiers. |

|

PROSPERO O, was she so? I must |

|

Once in a month recount what thou hast been, |

|

Which thou forget’st. This damned witch Sycorax, |

|

For mischiefs manifold and sorceries terrible |

|

To enter human hearing, from Algiers, |

265 |

Thou knowst, was banished. For one thing she did |

|

They would not take her life; is not this true? |

|

ARIEL Ay, sir. |

|

PROSPERO |

|

This blue-eyed hag was hither brought with child, |

|

And here was left by th’ sailors. Thou, my slave, |

270 |

As thou report’st thyself, was then her servant, |

|

And – for thou wast a spirit too delicate |

|

To act her earthy and abhorred commands, |

|

Refusing her grand hests – she did confine thee, |

|

By help of her more potent ministers |

275 |

And in her most unmitigable rage, |

|

Into a cloven pine, within which rift |

|

Imprisoned thou didst painfully remain |

|

A dozen years, within which space she died |

|

And left thee there, where thou didst vent thy groans |

280 |

As fast as millwheels strike. Then was this island |

|

(Save for the son that she did litter here, |

|

A freckled whelp, hag-born) not honoured with |

|

A human shape. |

|

ARIEL Yes, Caliban, her son. |

|

PROSPERO Dull thing, I say so – he, that Caliban, |

285 |

Whom now I keep in service. Thou best knowst |

|

What torment I did find thee in: thy groans |

|

Did make wolves howl and penetrate the breasts |

|

Of ever-angry bears. It was a torment |

|

To lay upon the damned, which Sycorax |

290 |

Could not again undo. It was mine art, |

|

When I arrived and heard thee, that made gape |

|

The pine and let thee out. |

|

ARIEL I thank thee, master. |

|

PROSPERO If thou more murmur’st, I will rend an oak |

|

And peg thee in his knotty entrails till |

295 |

Thou hast howled away twelve winters. |

|

ARIEL Pardon, master, |

|

I will be correspondent to command |

|

And do my spriting gently. |

|

PROSPERO Do so, and after two days |

|

I will discharge thee. |

|

ARIEL That’s my noble master. |

300 |

What shall I do? Say what? What shall I do? |

|

PROSPERO Go make thyself like a nymph o’th’ sea; |

|

Be subject to no sight but thine and mine, invisible |

|

To every eyeball else. Go take this shape |

|

And hither come in’t. Go! Hence with diligence. |

305 |

Exit Ariel. |

|

[to Miranda] Awake, dear heart, awake; thou hast slept |

|

well. |

|

Awake. |

|

MIRANDA The strangeness of your story put |

|

Heaviness in me. |

|

PROSPERO Shake it off. Come on, |

|

We’ll visit Caliban, my slave, who never |

|

Yields us kind answer. |

|

MIRANDA ’Tis a villain, sir, |

310 |

I do not love to look on. |

|

PROSPERO But as ’tis, |

|

We cannot miss him; he does make our fire, |

|

Fetch in our wood, and serves in offices |

|

That profit us. – What ho, slave! Caliban, |

|

Thou earth, thou: speak! |

|

CALIBAN [within] There’s wood enough within. |

315 |

PROSPERO |

|

Come forth I say, there’s other business for thee. |

|

Come, thou tortoise, when? |

|

Enter ARIEL, like a water nymph. |

|

Fine apparition, my quaint Ariel, |

|

Hark in thine ear. |

|

ARIEL My lord, it shall be done. Exit. |

|

PROSPERO |

|

Thou poisonous slave, got by the devil himself |

320 |

Upon thy wicked dam; come forth! |

|

Enter CALIBAN. |

|

CALIBAN As wicked dew as ere my mother brushed |

|

With raven’s feather from unwholesome fen |

|

Drop on you both. A southwest blow on ye |

|

And blister you all o’er. |

325 |

PROSPERO |

|

For this, be sure, tonight thou shalt have cramps, |

|

Side-stitches, that shall pen thy breath up; urchins |

|

Shall forth at vast of night that they may work |

|

All exercise on thee; thou shalt be pinched |

|

As thick as honeycomb, each pinch more stinging |

330 |

Than bees that made ’em. |

|

CALIBAN I must eat my dinner. |

|

This island’s mine by Sycorax, my mother, |

|

Which thou tak’st from me. When thou cam’st first |

|

Thou strok’st me and made much of me; wouldst |

|

give me |

|

Water with berries in’t, and teach me how |

335 |

To name the bigger light and how the less |

|

That burn by day and night. And then I loved thee |

|

And showed thee all the qualities o’th’ isle: |

|

The fresh springs, brine pits, barren place and fertile. |

|

Cursed be I that did so! All the charms |

340 |

Of Sycorax – toads, beetles, bats – light on you, |

|

For I am all the subjects that you have, |

|

Which first was mine own king; and here you sty me |

|

In this hard rock, whiles you do keep from me |

|

The rest o’th’ island. |

|

PROSPERO Thou most lying slave, |

345 |

Whom stripes may move, not kindness; I have used thee |

|

(Filth as thou art) with humane care and lodged thee |

|

In mine own cell, till thou didst seek to violate |

|

The honour of my child. |

|

CALIBAN O ho, O ho! Would’t had been done; |

350 |

Thou didst prevent me, I had peopled else |

|

This isle with Calibans. |

|

MIRANDA Abhorred slave, |

|

Which any print of goodness wilt not take, |

|

Being capable of all ill; I pitied thee, |

|

Took pains to make thee speak, taught thee each hour |

355 |

One thing or other. When thou didst not, savage, |

|

Know thine own meaning, but wouldst gabble like |

|

A thing most brutish, I endowed thy purposes With |

|

words that made them known. But thy vile race |

|

(Though thou didst learn) had that in’t which good natures |

360 |

Could not abide to be with; therefore wast thou |

|

Deservedly confined into this rock, |

|

Who hadst deserved more than a prison. |

|

CALIBAN You taught me language, and my profit on’t |

|

Is I know how to curse. The red plague rid you |

365 |

For learning me your language. |

|

PROSPERO Hag-seed, hence: |

|

Fetch us in fuel, and be quick – thou’rt best – |

|

To answer other business. Shrug’st thou, malice? |

|

If thou neglect’st, or dost unwillingly |

|

What I command, I’ll rack thee with old cramps, |

370 |

Fill all thy bones with aches, make thee roar, |

|

That beasts shall tremble at thy din. |

|

CALIBAN No, pray thee. |

|

[aside] I must obey; his art is of such power |

|

It would control my dam’s god Setebos, |

|

And make a vassal of him. |

|

PROSPERO So, slave, hence. |

375 |

Exit Caliban. |

|

Enter FERDINAND, and ARIEL, invisible, playing and singing. |

|

ARIEL [Sings.] |

|

Come unto these yellow sands, And then take hands; |

|

And then take hands; |

|

Curtsied when you have, and kissed The wild waves whist; |

|

The wild waves whist; |

|

Foot it featly here and there, |

380 |

And sweet sprites bear |

|

The burden. |

|

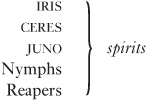

[Burden dispersedly] |

|

SPIRITS Hark, hark! Bow-wow, |

|

The watch dogs bark, bow-wow. |

|

ARIEL Hark hark, I hear, |

385 |

The strain of strutting chanticleer |

|

Cry cock a diddle dow. |

|

FERDINAND |

|

Where should this music be? I’th’ air, or th’earth? |

|

It sounds no more, and sure it waits upon |

|

Some god o’th’ island. Sitting on a bank, |

390 |

Weeping again the King my father’s wreck, |

|

This music crept by me upon the waters, |

|

Allaying both their fury and my passion |

|

With its sweet air. Thence I have followed it |

|

(Or it hath drawn me, rather) but ’tis gone. |

395 |

No, it begins again. |

|

ARIEL [Sings.] |

|

Full fathom five thy father lies, |

|

Of his bones are coral made; |

|

Those are pearls that were his eyes, |

|

Nothing of him that doth fade |

400 |

But doth suffer a sea-change |

|

Into something rich and strange. |

|

Sea nymphs hourly ring his knell. |

|

SPIRITS Ding dong. |

|

ARIEL Hark, now I hear them. |

|

SPIRITS Ding dong bell. |

405 |

FERDINAND |

|

The ditty does remember my drowned father; |

|

This is no mortal business nor no sound |

|

That the earth owes. I hear it now above me. |

|

PROSPERO [to Miranda] |

|

The fringed curtains of thine eye advance, And say what thou seest yond. |

|

And say what thou seest yond. |

|

MIRANDA What is’t, a spirit? |

410 |

Lord, how it looks about. Believe me, sir, |

|

It carries a brave form. But ’tis a spirit. |

|

PROSPERO |

|

No, wench, it eats and sleeps and hath such senses |

|

As we have – such. This gallant which thou seest |

|

Was in the wreck, and but he’s something stained |

415 |

With grief (that’s beauty’s canker) thou mightst call him |

|

A goodly person. He hath lost his fellows |

|

And strays about to find ’em. |

|

MIRANDA I might call him |

|

A thing divine, for nothing natural I ever saw so noble. |

|

PROSPERO [aside] It goes on, I see, |

420 |

As my soul prompts it. [to Ariel] Spirit, fine spirit, |

|

I’ll free thee |

|

Within two days for this. |

|

FERDINAND Most sure the goddess |

|

On whom these airs attend! – Vouchsafe my prayer |

|

May know if you remain upon this island, |

|

And that you will some good instruction give |

425 |

How I may bear me here. My prime request, |

|

Which I do last pronounce, is (O, you wonder!) |

|

If you be maid or no? |

|

MIRANDA No wonder, sir, |

|

But certainly a maid. |

|

FERDINAND My language? Heavens! |

|

I am the best of them that speak this speech, |

430 |

Were I but where ’tis spoken. |

|

PROSPERO How? The best? |

|

What wert thou if the King of Naples heard thee? |

|

FERDINAND A single thing, as I am now, that wonders |

|

To hear thee speak of Naples. He does hear me, |

|

And that he does, I weep. Myself am Naples, |

435 |

Who, with mine eyes, never since at ebb, beheld |

|

The King my father wrecked. |

|

MIRANDA Alack, for mercy! |

|

FERDINAND |

|

Yes, faith, and all his lords – the Duke of Milan |

|

And his brave son being twain. |

|

PROSPERO [aside] The Duke of Milan |

|

And his more braver daughter could control thee |

440 |

If now ’twere fit to do’t. At the first sight |

|

They have changed eyes. [to Ariel] Delicate Ariel, |

|

I’ll set thee free for this. [to Ferdinand] A word, good sir; |

|

I fear you have done yourself some wrong. A word. |

|

MIRANDA [aside] |

|

Why speaks my father so ungently? This |

445 |

Is the third man that e’er I saw, the first |

|

That e’er I sighed for. Pity move my father |

|

To be inclined my way. |

|

FERDINAND O, if a virgin, |

|

And your affection not gone forth, I’ll make you |

|

The Queen of Naples. |

|

PROSPERO Soft, sir, one word more. |

450 |

[aside] They are both in either’s powers, but this |

|

swift business |

|

I must uneasy make, lest too light winning |

|

Make the prize light. [to Ferdinand] One word more. |

|

I charge thee |

|

That thou attend me. Thou dost here usurp |

|

The name thou ow’st not and hast put thyself |

455 |

Upon this island as a spy, to win it |

|

From me, the lord on’t. |

|

FERDINAND No, as I am a man. |

|

MIRANDA |

|

There’s nothing ill can dwell in such a temple. |

|

If the ill spirit have so fair a house, |

|

Good things will strive to dwell with’t. |

|

PROSPERO [to Ferdinand] Follow me. – |

460 |

Speak not you for him; he’s a traitor. – Come, |

|

I’ll manacle thy neck and feet together; |

|

Sea water shalt thou drink; thy food shall be |

|

The fresh-brook mussels, withered roots, and husks |

|

Wherein the acorn cradled. Follow! |

|

FERDINAND No, |

465 |

I will resist such entertainment till |

|

Mine enemy has more power. |

|

[He draws and is charmed from moving.] |

|

MIRANDA O dear father, |

|

Make not too rash a trial of him, for |

|

He’s gentle and not fearful. |

|

PROSPERO What, I say, |

|

My foot my tutor? Put thy sword up, traitor, |

470 |

Who mak’st a show but dar’st not strike, thy conscience |

|

Is so possessed with guilt. Come from thy ward, |

|

For I can here disarm thee with this stick |

|

And make thy weapon drop. |

|

MIRANDA Beseech you, father – |

|

PROSPERO Hence; hang not on my garments. |

|

MIRANDA Sir, have pity; |

475 |

I’ll be his surety. |

|

PROSPERO Silence! One word more |

|

Shall make me chide thee, if not hate thee. What, |

|

An advocate for an impostor? Hush. |

|

Thou think’st there is no more such shapes as he, |

|

Having seen but him and Caliban. Foolish wench, |

480 |

To th’ most of men, this is a Caliban, |

|

And they to him are angels. |

|

MIRANDA My affections |

|

Are then most humble. I have no ambition |

|

To see a goodlier man. |

|

PROSPERO [to Ferdinand] Come on, obey: |

|

Thy nerves are in their infancy again |

485 |

And have no vigour in them. |

|

FERDINAND So they are! |

|

My spirits, as in a dream, are all bound up. |

|

My father’s loss, the weakness which I feel, |

|

The wreck of all my friends, nor this man’s threats |

|

(To whom I am subdued) are but light to me, |

490 |

Might I but through my prison once a day |

|

Behold this maid. All corners else o’th’ earth |

|

Let liberty make use of; space enough |

|

Have I in such a prison. |

|

PROSPERO [aside] It works. [to Ferdinand] Come on. – |

|

Thou hast done well, fine Ariel. – Follow me; – |

495 |

Hark what thou else shalt do me. |

|

MIRANDA [to Ferdinand] Be of comfort; |

|

My father’s of a better nature, sir, |

|

Than he appears by speech. This is unwonted |

|

Which now came from him. |

|

PROSPERO [to Ariel] Thou shalt be as free |

|

As mountain winds, but then exactly do |

500 |

All points of my command. |

|

ARIEL To th’ syllable. |

|

PROSPERO [to Ferdinand] |

|

Come, follow; – speak not for him. |

|

Exeunt. |

|

GONZALO Beseech you, sir, be merry. You have cause |

|

(So have we all) of joy, for our escape |

|

Is much beyond our loss. Our hint of woe |

|

Is common: every day some sailor’s wife, |

|

The masters of some merchant, and the merchant, |

5 |

Have just our theme of woe. But for the miracle, |

|

I mean our preservation, few in millions |

|

Can speak like us. Then wisely, good sir, weigh |

|

Our sorrow with our comfort. |

|

ALONSO Prithee, peace. |

|

SEBASTIAN [to Antonio] He receives comfort like cold |

10 |

porridge. |

|

ANTONIO [to Sebastian] The visitor will not give him |

|

o’er so. |

|

SEBASTIAN Look, he’s winding up the watch of his wit; |

|

by and by it will strike – |

15 |

GONZALO [to Alonso] Sir – |

|

SEBASTIAN One. Tell. |

|

GONZALO When every grief is entertained that’s |

|

offered, comes to th’entertainer – |

|

SEBASTIAN A dollar. |

20 |

GONZALO Dolour comes to him, indeed. You have |

|

spoken truer than you purposed. |

|

SEBASTIAN You have taken it wiselier than I meant you |

|

should. |

|

GONZALO Therefore, my lord – |

25 |

ANTONIO Fie, what a spendthrift is he of his tongue! |

|

ALONSO I prithee, spare. |

|

GONZALO Well, I have done; but yet – |

|

SEBASTIAN He will be talking. |

|

ANTONIO Which, of he or Adrian, for a good wager, |

30 |

first begins to crow? |

|

SEBASTIAN The old cock. |

|

ANTONIO The cockerel. |

|

SEBASTIAN Done! The wager? |

|

ANTONIO A laughter. |

35 |

SEBASTIAN A match! |

|

ADRIAN Though this island seem to be desert – |

|

ANTONIO Ha, ha, ha. |

|

SEBASTIAN So, you’re paid. |

|

ADRIAN Uninhabitable and almost inaccessible – |

40 |

SEBASTIAN Yet – |

|

ADRIAN Yet – |

|

ANTONIO He could not miss’t. |

|

ADRIAN It must needs be of subtle, tender and delicate |

|

temperance. |

45 |

ANTONIO Temperance was a delicate wench. |

|

SEBASTIAN Ay, and a subtle, as he most learnedly |

|

delivered. |

|

ADRIAN The air breathes upon us here most sweetly. |

|

SEBASTIAN As if it had lungs, and rotten ones. |

50 |

ANTONIO Or, as ’twere perfumed by a fen. |

|

GONZALO Here is everything advantageous to life. |

|

ANTONIO True, save means to live. |

|

SEBASTIAN Of that there’s none, or little. |

|

GONZALO How lush and lusty the grass looks! How green! |

55 |

ANTONIO The ground indeed is tawny. |

|

SEBASTIAN With an eye of green in’t. |

|

ANTONIO He misses not much. |

|

SEBASTIAN No; he doth but mistake the truth totally. |

|

GONZALO But the rarity of it is, which is indeed almost |

60 |

beyond credit – |

|

SEBASTIAN As many vouched rarities are. |

|

GONZALO That our garments being, as they were, |

|

drenched in the sea, hold notwithstanding their |

|

freshness and gloss, being rather new-dyed than |

65 |

stained with salt water. |

|

ANTONIO If but one of his pockets could speak, would it |

|

not say he lies? |

|

SEBASTIAN Ay, or very falsely pocket up his report. |

|

GONZALO Methinks our garments are now as fresh as |

70 |

when we put them on first in Africa, at the marriage of |

|

the King’s fair daughter Claribel to the King of Tunis. |

|

SEBASTIAN ’Twas a sweet marriage, and we prosper |

|

well in our return. |

|

ADRIAN Tunis was never graced before with such a |

75 |

paragon to their queen. |

|

GONZALO Not since widow Dido’s time. |

|

ANTONIO Widow? A pox o’that. How came that widow |

|

in? Widow Dido! |

|

SEBASTIAN What if he had said widower Aeneas too? |

80 |

Good lord, how you take it! |

|

ADRIAN Widow Dido, said you? You make me study of |

|

that. She was of Carthage, not of Tunis. |

|

GONZALO This Tunis, sir, was Carthage. |

|

ADRIAN Carthage? |

85 |

GONZALO I assure you, Carthage. |

|

ANTONIO His word is more than the miraculous harp. |

|

SEBASTIAN He hath raised the wall, and houses too. |

|

ANTONIO What impossible matter will he make easy |

|

next? |

90 |

SEBASTIAN I think he will carry this island home in his |

|

pocket and give it his son for an apple. |

|

ANTONIO And sowing the kernels of it in the sea, bring |

|

forth more islands! |

|

GONZALO I – |

95 |

ANTONIO Why, in good time. |

|

GONZALO Sir, we were talking that our garments seem |

|

now as fresh as when we were at Tunis at the marriage |

|

of your daughter, who is now Queen. |

|

ANTONIO And the rarest that e’er came there. |

100 |

SEBASTIAN Bate, I beseech you, widow Dido. |

|

ANTONIO O, widow Dido? Ay, widow Dido. |

|

GONZALO Is not, sir, my doublet as fresh as the first |

|

day I wore it? I mean, in a sort. |

|

ANTONIO That sort was well fished for. |

105 |

GONZALO When I wore it at your daughter’s marriage. |

|

ALONSO You cram these words into mine ears, against |

|

The stomach of my sense. Would I had never |

|

Married my daughter there, for coming thence |

|

My son is lost and (in my rate) she too, |

110 |

Who is so far from Italy removed |

|

I ne’er again shall see her. O thou mine heir |

|

Of Naples and of Milan, what strange fish |

|

Hath made his meal on thee? |

|

FRANCISCO Sir, he may live. |

|

I saw him beat the surges under him |

115 |

And ride upon their backs. He trod the water, |

|

Whose enmity he flung aside, and breasted |

|

The surge most swoll’n that met him. His bold head |

|

’Bove the contentious waves he kept and oared |

|

Himself with his good arms in lusty stroke |

120 |

To th’ shore, that o’er his wave-worn basis bowed, |

|

As stooping to relieve him. I not doubt |

|

He came alive to land. |

|

ALONSO No, no, he’s gone. |

|

SEBASTIAN |

|

Sir, you may thank yourself for this great loss, |

|

That would not bless our Europe with your daughter |

125 |

But rather loose her to an African, |

|

Where she at least is banished from your eye, |

|

Who hath cause to wet the grief on’t. |

|

ALONSO Prithee, peace. |

|

SEBASTIAN |

|

You were kneeled to and importuned otherwise |

|

By all of us, and the fair soul herself |

130 |

Weighed between loathness and obedience, at |

|

Which end o’th’ beam should bow. We have lost your son, |

|

I fear, for ever. Milan and Naples have |

|

More widows in them of this business’ making |

|

Than we bring men to comfort them. |

135 |

The fault’s your own. |

|

ALONSO So is the dear’st o’th’ loss. |

|

GONZALO My lord Sebastian, |

|

The truth you speak doth lack some gentleness, |

|

And time to speak it in. You rub the sore |

|

When you should bring the plaster. |

140 |

SEBASTIAN Very well. |

|

ANTONIO And most chirurgeonly! |

|

GONZALO It is foul weather in us all, good sir, |

|

When you are cloudy. |

|

SEBASTIAN Foul weather? |

|

ANTONIO Very foul. |

|

GONZALO Had I plantation of this isle, my lord – |

|

ANTONIO He’d sow’t with nettle-seed. |

|

SEBASTIAN Or docks, or mallows. |

145 |

GONZALO And were the king on’t, what would I do? |

|

SEBASTIAN ’Scape being drunk, for want of wine. |

|

GONZALO I’th’ commonwealth I would by contraries |

|

Execute all things, for no kind of traffic |

|

Would I admit; no name of magistrate; |

150 |

Letters should not be known; riches, poverty |

|

And use of service, none; contract, succession, |

|

Bourn, bound of land, tilth, vineyard – none; |

|

No use of metal, corn, or wine or oil; |

|

No occupation, all men idle, all; |

155 |

And women, too, but innocent and pure; |

|

No sovereignty – |

|

SEBASTIAN Yet he would be king on’t. |

|

ANTONIO The latter end of his commonwealth forgets |

|

the beginning. |

|

GONZALO |

|

All things in common nature should produce |

160 |

Without sweat or endeavour; treason, felony, |

|

Sword, pike, knife, gun, or need of any engine |

|

Would I not have; but nature should bring forth |

|

Of its own kind all foison, all abundance, |

|

To feed my innocent people. |

165 |

SEBASTIAN No marrying ’mong his subjects? |

|

ANTONIO None, man, all idle – whores and knaves. |

|

GONZALO I would with such perfection govern, sir, |

|

T’excel the Golden Age. |

|

SEBASTIAN ’Save his majesty! |

|

ANTONIO Long live Gonzalo! |

170 |

GONZALO And – do you mark me, sir? – |

|

ALONSO Prithee, no more. |

|

Thou dost talk nothing to me. |

|

GONZALO I do well believe your highness, and did it to |

|

minister occasion to these gentlemen, who are of such |

|

sensible and nimble lungs that they always use to |

175 |

laugh at nothing. |

|

ANTONIO ’Twas you we laughed at. |

|

GONZALO Who, in this kind of merry fooling, am |

|

nothing to you, so you may continue and laugh at |

|

nothing still. |

180 |

ANTONIO What a blow was there given! |

|

SEBASTIAN An it had not fallen flat-long. |

|

GONZALO You are gentlemen of brave mettle. You |

|

would lift the moon out of her sphere, if she would |

|

continue in it five weeks without changing. |

185 |

Enter ARIEL playing solemn music. |

|

SEBASTIAN We would so, and then go a bat-fowling. |

|

ANTONIO Nay, good my lord, be not angry. |

|

GONZALO No, I warrant you, I will not adventure my |

|

discretion so weakly. Will you laugh me asleep, for I |

|

am very heavy. |

190 |

ANTONIO Go sleep, and hear us. |

|

[All sleep except Alonso, Sebastian and Antonio.] |

|

ALONSO What, all so soon asleep? I wish mine eyes |

|

Would, with themselves, shut up my thoughts. I find |

|

They are inclined to do so. |

|

SEBASTIAN Please you, sir, |

|

Do not omit the heavy offer of it. |

195 |

It seldom visits sorrow; when it doth, |

|

It is a comforter. |

|

ANTONIO We two, my lord, |

|

Will guard your person while you take your rest, |

|

And watch your safety. |

|

ALONSO Thank you. Wondrous heavy. |

|

[Alonso sleeps. Exit Ariel.] |

|

SEBASTIAN What a strange drowsiness possesses them! |

200 |

ANTONIO It is the quality o’th’ climate. |

|

SEBASTIAN Why |

|

Doth it not then our eyelids sink? I find not |

|

Myself disposed to sleep. |

|

ANTONIO Nor I. My spirits are nimble. |

|

They fell together all, as by consent; |

|

They dropped, as by a thunderstroke. What might, |

205 |

Worthy Sebastian, O, what might –? No more; |

|

And yet, methinks I see it in thy face |

|

What thou shouldst be. Th’occasion speaks thee, and |

|

My strong imagination sees a crown |

|

Dropping upon thy head. |

|

SEBASTIAN What, art thou waking? |

210 |

ANTONIO Do you not hear me speak? |

|

SEBASTIAN I do, and surely |

|

It is a sleepy language, and thou speak’st |

|

Out of thy sleep. What is it thou didst say? |

|

This is a strange repose, to be asleep |

|

With eyes wide open – standing, speaking, moving, |

215 |

And yet so fast asleep. |

|

ANTONIO Noble Sebastian, |

|

Thou let’st thy fortune sleep – die rather; wink’st |

|

Whiles thou art waking. |

|

SEBASTIAN Thou dost snore distinctly. |

220 |

There’s meaning in thy snores. |

|

ANTONIO I am more serious than my custom. You |

|

Must be so too, if heed me, which to do |

|

Trebles thee o’er. |

|

SEBASTIAN Well, I am standing water. |

|

ANTONIO I’ll teach you how to flow. |

|

SEBASTIAN Do so. To ebb |

|

Hereditary sloth instructs me. |

|

ANTONIO O, |

|

If you but knew how you the purpose cherish |

225 |

Whiles thus you mock it, how in stripping it |

|

You more invest it. Ebbing men, indeed, |

|

Most often do so near the bottom run |

|

By their own fear or sloth. |

|

SEBASTIAN Prithee, say on; |

|

The setting of thine eye and cheek proclaim |

230 |

A matter from thee, and a birth, indeed, |

|

Which throes thee much to yield. |

|

ANTONIO Thus, sir: |

|

Although this lord of weak remembrance – this |

|

Who shall be of as little memory |

|

When he is earthed – hath here almost persuaded |

235 |

(For he’s a spirit of persuasion, only |

|

Professes to persuade) the King his son’s alive, |

|

’Tis as impossible that he’s undrowned |

|

As he that sleeps here swims. |

|

SEBASTIAN I have no hope |

|

That he’s undrowned. |

|

ANTONIO O, out of that ‘no hope’, |

240 |

What great hope have you! No hope that way is |

|

Another way so high a hope that even |

|

Ambition cannot pierce a wink beyond, |

|

But doubt discovery there. Will you grant with me |

|

That Ferdinand is drowned? |

|

SEBASTIAN He’s gone. |

|

ANTONIO Then tell me, |

245 |

Who’s the next heir of Naples? |

|

SEBASTIAN Claribel. |

|

ANTONIO She that is Queen of Tunis; she that dwells |

|

Ten leagues beyond man’s life; she that from Naples |

|

Can have no note unless the sun were post – |

|

The man i’th’ moon’s too slow – till newborn chins |

250 |

Be rough and razorable; she that from whom |

|

We all were sea-swallowed, though some cast again, |

|

And by that destiny to perform an act |

|

Whereof what’s past is prologue, what to come |

|

In yours and my discharge! |

255 |

SEBASTIAN What stuff is this? How say you? |

|

’Tis true my brother’s daughter’s Queen of Tunis, |

|

So is she heir of Naples, ’twixt which regions |

|

There is some space. |

|

ANTONIO A space whose every cubit |

|

Seems to cry out, ‘How shall that Claribel |

260 |

Measure us back to Naples? Keep in Tunis, |

|

And let Sebastian wake.’ Say this were death |

|

That now hath seized them; why, they were no worse |

|

Than now they are. There be that can rule Naples |

|

As well as he that sleeps; lords that can prate |

265 |

As amply and unnecessarily |

|

As this Gonzalo. I myself could make |

|

A chough of as deep chat. O that you bore |

|

The mind that I do! What a sleep were this |

|

For your advancement! Do you understand me? |

270 |

SEBASTIAN Methinks I do. |

|

ANTONIO And how does your content |

|

Tender your own good fortune? |

|

SEBASTIAN I remember |

|

You did supplant your brother Prospero. |

|

ANTONIO True: |

|

And look how well my garments sit upon me |

|

Much feater than before. My brother’s servants |

275 |

Were then my fellows; now they are my men. |

|

SEBASTIAN But for your conscience? |

|

ANTONIO Ay, sir, where lies that? If ’twere a kibe |

|

’Twould put me to my slipper, but I feel not |

|

This deity in my bosom. Twenty consciences |

280 |

That stand ’twixt me and Milan, candied be they |

|

And melt ere they molest! Here lies your brother, |

|

No better than the earth he lies upon. |

|

If he were that which now he’s like (that’s dead) |

|

Whom I with this obedient steel – three inches of it – |

285 |

Can lay to bed forever (whiles you, doing thus, |

|

To the perpetual wink for aye might put |

|

This ancient morsel, this Sir Prudence, who |

|

Should not upbraid our course) – for all the rest |

|

They’ll take suggestion as a cat laps milk; |

290 |

They’ll tell the clock to any business that |

|

We say befits the hour. |

|

SEBASTIAN Thy case, dear friend, |

|

Shall be my precedent. As thou got’st Milan, |

|

I’ll come by Naples. Draw thy sword! One stroke |

|

Shall free thee from the tribute which thou payest, |

295 |

And I the king shall love thee. |

|

ANTONIO Draw together, |

|

And when I rear my hand, do you the like |

|

To fall it on Gonzalo. |

|

SEBASTIAN O, but one word – |

|

Enter ARIEL with music and song. |

|

ARIEL |

|

My master through his art foresees the danger |

|

That you, his friend, are in, and sends me forth |

300 |

(For else his project dies) to keep them living. |

|

[Sings in Gonzalo’s ear.] |

|

While you here do snoring lie, |

|

Open-eyed conspiracy |

|

His time doth take. |

|

If of life you keep a care, |

|

Shake off slumber and beware. |

305 |

Awake, awake! |

|

ANTONIO Then let us both be sudden. |

|

GONZALO [Wakes.] |

|

Now, good angels preserve the King! |

|

ALONSO [Wakes.] |

|

Why, how now, ho! Awake! Why are you drawn? |

|

Wherefore this ghastly looking? |

310 |

GONZALO What’s the matter? |

|

SEBASTIAN Whiles we stood here securing your repose, |

|

Even now we heard a hollow burst of bellowing, |

|

Like bulls, or rather lions. Did’t not wake you? |

|

It struck mine ear most terribly. |

|

ALONSO I heard nothing. |

315 |

ANTONIO O, ’twas a din to fright a monster’s ear – |

|

To make an earthquake! Sure it was the roar |

|

Of a whole herd of lions. |

|

ALONSO Heard you this, Gonzalo? |

|

GONZALO Upon mine honour, sir, I heard a humming, |

|

And that a strange one too, which did awake me. |

320 |

I shaked you, sir, and cried. As mine eyes opened, |

|

I saw their weapons drawn. There was a noise, |

|

That’s verily. ’Tis best we stand upon our guard, |

|

Or that we quit this place. Let’s draw our weapons. |

|

ALONSO |

|

Lead off this ground, and let’s make further search |

325 |

For my poor son. |

|

GONZALO Heavens keep him from these beasts, |

|

For he is, sure, i’th’ island. |

|

ALONSO Lead away. |

|

ARIEL Prospero, my lord, shall know what I have done; |

|

So, King, go safely on to seek thy son. Exeunt. |

|

CALIBAN All the infections that the sun sucks up |

|

From bogs, fens, flats, on Prosper fall, and make him |

|

By inchmeal a disease! His spirits hear me, |

|

And yet I needs must curse. But they’ll nor pinch, |

|

Fright me with urchin-shows, pitch me i’th’ mire, |

5 |

Nor lead me, like a firebrand in the dark, |

|

Out of my way unless he bid ’em. But |

|

For every trifle are they set upon me: |

|

Sometime like apes that mow and chatter at me |

|

And after bite me, then like hedgehogs which |

10 |

Lie tumbling in my barefoot way and mount |

|

Their pricks at my footfall. Sometime am I |

|

All wound with adders, who with cloven tongues |

|

Do hiss me into madness. Lo now, lo, |

|

Enter TRINCULO |

|

Here comes a spirit of his, and to torment me |

15 |

For bringing wood in slowly. I’ll fall flat; |

|

Perchance he will not mind me. |

|

TRINCULO Here’s neither bush nor shrub to bear off any |

|

weather at all, and another storm brewing; I hear it sing |

|

i’th’ wind. Yond same black cloud, yond huge one, |

20 |

looks like a foul bombard that would shed his liquor. If |

|

it should thunder as it did before, I know not where to |

|

hide my head. Yond same cloud cannot choose but fall |

|

by pailfuls. [Sees Caliban.] What have we here, a man |

|

or a fish? Dead or alive? A fish: he smells like a fish, a |

25 |

very ancient and fish-like smell, a kind of – not of the |

|

newest – poor-John. A strange fish! Were I in England |

|

now (as once I was) and had but this fish painted, not |

|

a holiday fool there but would give a piece of silver. |

|

There would this monster make a man; any strange |

30 |

beast there makes a man. When they will not give a |

|

doit to relieve a lame beggar, they will lay out ten to |

|

see a dead Indian. Legged like a man and his fins like |

|

arms! Warm, o’my troth! I do now let loose my |

|

opinion, hold it no longer: this is no fish, but an |

35 |

islander that hath lately suffered by a thunderbolt. |

|

Alas, the storm is come again. My best way is to creep |

|

under his gaberdine; there is no other shelter |

|

hereabout. Misery acquaints a man with strange |

|

bedfellows! I will here shroud till the dregs of the |

40 |

storm be past. |

|

Enter STEPHANO singing. |

|

STEPHANO I shall no more to sea, to sea, |

|

Here shall I die ashore. |

|

This is a very scurvy tune to sing at a man’s funeral. |

|

Well, here’s my comfort. [Drinks and then sings.] |

45 |

The master, the swabber, the boatswain and I; |

|

The gunner and his mate, |

|

Loved Mall, Meg, and Marian, and Margery, |

|

But none of us cared for Kate. |

|

For she had a tongue with a tang, |

50 |

Would cry to a sailor, ‘Go hang!’ |

|

She loved not the savour of tar nor of pitch, |

|

Yet a tailor might scratch her where’er she did itch. |

|

Then to sea, boys, and let her go hang! |

|

This is a scurvy tune too, but here’s my comfort. |

55 |

[Drinks.] |

|

CALIBAN Do not torment me! O! |

|

STEPHANO What’s the matter? Have we devils here? Do |

|

you put tricks upon’s with savages and men of Ind? |

|

Ha! I have not ’scaped drowning to be afeard now of |

|

your four legs; for it hath been said, ‘As proper a man |

60 |

as ever went on four legs cannot make him give |

|

ground’. And it shall be said so again while Stephano |

|

breathes at’ nostrils. |

|

CALIBAN The spirit torments me! O! |

|

STEPHANO This is some monster of the isle, with four |

65 |

legs, who hath got, as I take it, an ague. Where the devil |

|

should he learn our language? I will give him some |

|

relief, if it be but for that. If I can recover him and keep |

|

him tame, and get to Naples with him, he’s a present for |

|

any emperor that ever trod on neat’s leather. |

70 |

CALIBAN Do not torment me, prithee. I’ll bring my |

|

wood home faster. |

|

STEPHANO He’s in his fit now and does not talk after the |

|

wisest. He shall taste of my bottle; if he have never |

|

drunk wine afore, it will go near to remove his fit. If I |

75 |

can recover him and keep him tame, I will not take too |

|

much for him! He shall pay for him that hath him, and |

|

that soundly. |

|

CALIBAN Thou dost me yet but little hurt. Thou wilt |

|

anon, I know it by thy trembling. Now Prosper works |

80 |

upon thee. |

|

STEPHANO Come on your ways; open your mouth. Here |

|

is that which will give language to you, cat. Open your |

|

mouth! This will shake your shaking, I can tell you, |

|

and that soundly. [Pours into Caliban’s mouth.] You |

85 |

cannot tell who’s your friend. Open your chaps again. |

|

TRINCULO I should know that voice. It should be – but |

|

he is drowned, and these are devils. O, defend me! |

|

STEPHANO Four legs and two voices – a most delicate |

|

monster! His forward voice now is to speak well of his |

90 |

friend; his backward voice is to utter foul speeches and |

|

to detract. If all the wine in my bottle will recover him, |

|

I will help his ague. Come. Amen! I will pour some in |

|

thy other mouth. |

|

TRINCULO Stephano! |

95 |

STEPHANO Doth thy other mouth call me? Mercy, |

|

mercy! This is a devil and no monster. I will leave him; |

|

I have no long spoon. |

|

TRINCULO Stephano? If thou be’st Stephano, touch me |

|

and speak to me, for I am Trinculo! Be not afeard – thy |

100 |

good friend Trinculo. |

|

STEPHANO If thou be’st Trinculo, come forth. I’ll pull |

|

thee by the lesser legs. If any be Trinculo’s legs, these |

|

are they. [Pulls him from under the cloak.] Thou art very |

|

Trinculo indeed! How cam’st thou to be the siege of |

105 |

this mooncalf? Can he vent Trinculos? |

|

TRINCULO I took him to be killed with a thunderstroke. |

|

But art thou not drowned, Stephano? I hope now thou |

|

art not drowned. Is the storm overblown? I hid me |

|

under the dead mooncalf’s gaberdine for fear of the |

110 |

storm. And art thou living, Stephano? O Stephano, |

|

two Neapolitans ’scaped? |

|

STEPHANO Prithee, do not turn me about; my stomach |

|

is not constant. |

|

CALIBAN |

|

These be fine things, an if they be not sprites; |

115 |

That’s a brave god and bears celestial liquor. |

|

I will kneel to him. |

|

STEPHANO How didst thou scape? How cam’st thou |

|

hither? Swear by this bottle how thou cam’st hither. I |

|

escaped upon a butt of sack, which the sailors heaved |

120 |

o’erboard – by this bottle, which I made of the bark of |

|

a tree with mine own hands since I was cast ashore. |

|

CALIBAN I’ll swear upon that bottle to be thy true |

|

subject, for the liquor is not earthly. |

|

STEPHANO Here, swear then how thou escaped’st. |

125 |

TRINCULO Swum ashore, man, like a duck. I can swim |

|

like a duck, I’ll be sworn. |

|

STEPHANO Here, kiss the book. [Trinculo drinks.] |

|

Though thou canst swim like a duck, thou art made |

|

like a goose. |

130 |

TRINCULO O Stephano, hast any more of this? |

|

STEPHANO The whole butt, man. My cellar is in a rock |

|

by th’ seaside, where my wine is hid. How now, |

|

mooncalf, how does thine ague? |

|

CALIBAN Hast thou not dropped from heaven? |

135 |

STEPHANO Out o’th’ moon, I do assure thee. I was the |

|

man i’th’ moon when time was. |

|

CALIBAN |

|

I have seen thee in her, and I do adore thee! |

|

My mistress showed me thee, and thy dog and thy |

|

bush. |

|

STEPHANO Come, swear to that. Kiss the book. I will |

140 |

furnish it anon with new contents. Swear! |

|

[Caliban drinks.] |

|

TRINCULO By this good light, this is a very shallow |

|

monster. I afeard of him? A very weak monster. The |

|

man i’th’ moon? A most poor credulous monster! Well |

|

drawn, monster, in good sooth. |

145 |

CALIBAN I’ll show thee every fertile inch o’th’ island, |

|

And I will kiss thy foot. I prithee, be my god. |

|

TRINCULO By this light, a most perfidious and drunken |

|

monster; when’s god’s asleep, he’ll rob his bottle. |

|

CALIBAN I’ll kiss thy foot. I’ll swear myself thy subject. |

150 |

STEPHANO Come on, then, down and swear. |

|

TRINCULO I shall laugh myself to death at this puppy- |

|

headed monster. A most scurvy monster. I could find |

|

in my heart to beat him – |

|

STEPHANO Come, kiss. |

155 |

TRINCULO But that the poor monster’s in drink. An |

|

abominable monster! |

|

CALIBAN |

|

I’ll show thee the best springs; I’ll pluck thee berries; |

|

I’ll fish for thee, and get thee wood enough. |

|

A plague upon the tyrant that I serve! |

160 |

I’ll bear him no more sticks but follow thee, |

|

Thou wondrous man. |

|

TRINCULO A most ridiculous monster – to make a |

|

wonder of a poor drunkard! |

|

CALIBAN I prithee, let me bring thee where crabs grow, |

165 |

And I with my long nails will dig thee pignuts, |

|

Show thee a jay’s nest, and instruct thee how |

|

To snare the nimble marmoset. I’ll bring thee |

|

To clust’ring filberts, and sometimes I’ll get thee |

|

Young scamels from the rock. Wilt thou go with me? |

170 |

STEPHANO I prithee, now, lead the way without any more |

|

talking. Trinculo, the King and all our company else |

|

being drowned, we will inherit here. Here, bear my |

|

bottle. Fellow Trinculo, we’ll fill him by and by again. |

|

CALIBAN [Sings drunkenly.] |

|

Farewell, master; farewell, farewell! |

175 |

TRINCULO A howling monster, a drunken monster! |

|

CALIBAN No more dams I’ll make for fish, |

|

Nor fetch in firing at requiring, |

|

Nor scrape trenchering, nor wash dish. |

|

Ban’ ban’ Ca-caliban, |

180 |

Has a new master, get a new man. |

|

Freedom, high-day; high-day freedom; freedom high- |

|

day, freedom. |

|

STEPHANO O brave monster, lead the way. Exeunt. |

|