7 • Mad Poets: Dylan Thomas and John Berryman

Coursing through the frozen prairie in 1950 aboard a night train from Chicago to Iowa City, where he was scheduled to deliver a highly anticipated reading hosted by the Iowa Writers’ Workshop and attended by the wider campus community, the world-renowned Welsh poet Dylan Thomas did what came naturally—he imbibed with the locals. As famous as he was, Thomas was never more comfortable than at a bar cavorting with perfect strangers, swapping tales, and filling the room with his raucous wit and Welsh-English brogue. The fellow travelers he fell in with in this case were hard-drinking truck drivers, whose conviviality was not below this poet renowned for his BBC broadcasts and poetry volume Deaths and Entrances, published in 1946, that established him as a major literary figure. With Thomas in the mix, the otherwise drab dining car on this blindingly boring four-hour journey west across the Mississippi River valley was overflowing with high spirits. Thomas had boarded the train sober; but when Workshop faculty member Ray B. West, Jr., arrived to shuttle him to his speaking engagement, set to take place in the Senate Chamber of the Old Capitol just a few hours later, the poet was dead drunk. As West helped him from the train, Thomas bellowed in agony, “This is the night I don’t go on!”1

Given the high stakes of Thomas’s visit, a fast and furious remedy was necessary. Staff and administration had been long preparing for his arrival, rolling out the red carpet for this distinguished guest by situating his talk in the majestic gold-domed Old Capitol building, the architectural crown jewel at the heart of campus reserved for only the most auspicious occasions. Barely able to walk, Thomas was beside himself muttering an incoherent slur of profanity-laced epithets, disheveled and in no shape to face the university community’s top brass. High-profile representatives from the publishing industry, including Seymour Lawrence, were also in attendance. This was a cast carefully arranged by Workshop director Paul Engle to be a glittering spectacle for potential investors in the program and to stimulate the professional development of his students. West knew the show must go on.

Thinking fast, West went where most Workshop faculty and students gravitated when facing an acute crisis, whether financial, personal, or creative—the Quonset hut main office situated a short distance down the hill from the Old Capitol building. Like Gabriel piloting the obliterated Freddy Malins across the dance floor and out of view for the sake of decency in James Joyce’s “The Dead,” West rushed Thomas into the office bathroom, which had an actual tub, dunked him in ice-cold water, helped him back into his clothes, and ushered him up the hill to the awaiting packed audience of literati and dignitaries in the stately confines of the Senate Chamber. Miraculously, as W. D. Snodgrass recalled, “he delivered one of his most beautiful readings,” fully living up to the occasion Robert Lowell’s introduction described in superlative terms. The purpose of the event, Lowell said, was “to hear an important poet, perhaps the most important of our time—a poet who had altered the modern trend, who seemed to have sprung from a different tradition than most poets today, who had revived what seemed to be a romantic sensibility at its best,” as West later paraphrased it. His reading was mellifluous and powerful; “his syllables penetrated the far corners of the hall, each word distinct from the next, so that it seemed to hover a moment in the air like the flare of a rocket before giving way to the next one.” The fireworks were delivered with a stately grace one could imagine of Lord Byron himself, his voice “sonorous and nearly Shakespearean” as he held the book with his arm theatrically extended. Between passages his arm lowered and his eyes glazed over. The public stage persona of the poetry reader, a consummate professional, transformed into the private romantic bohemian, a waggish buffoon whose “speech was slurred, shambling, obscene.”2 Then, beginning to read again, he raised his head, extended the book and shifted back into character, summoning back the oracular “strange compelling music of his native Welsh diction.” Occasionally he would pause to pick up a glass of water, only to regard it with a look of horror and replace it quickly on the table, the chill of his jarring ice bath still deep in his bones. That “strange and wild” voice overwhelmed the room, leaving listeners marveling. “There is nothing like Dylan Thomas in poetry today. There is a wholeness, a harmony, a radiance about everything he has written which sets him apart,” as Lawrence Ferlinghetti described his later performance in San Francisco in 1952.3

Thomas was the most notorious reckless romantic of his era, and his hostility to academic literary critics—he detested their “bloody nit picking”—paradoxically made him more attractive to university audiences.4 Literary critics and creative writing teachers especially found appealing the authenticity of this performing poet, seemingly from another era, who lived for the music of verse.5 From his early BBC days, oratorical performance was his strong suit; a Thomas poem was always better read in his own voice than silently on the printed page. In addition to influencing the faculty and students on the many college campuses where he read, “the tradition of oral poetry Thomas presented became a model as well for many of the younger poets who were to constitute the heart of the San Francisco Renaissance—the Beat Generation,” as Beat historian Barry Silesky observes.6

Iowa was but one stop on his whirlwind tour of the United States that began in late February of 1950 and was intended to showcase that charismatic voice. Thomas’s proclamation that this was the night he would not go on, which spurred the horrified West into action to ensure that he did, exposed his fear that his bacchanalian lifestyle might prevent him from meeting all the dates on the frantic schedule set by his agent, John Malcolm Brinnin. Starting at Yale and Harvard, he made stops for readings throughout New England and proceeded to the Midwest, which included the Universities of Chicago, Illinois, and Notre Dame before his journey by train to Iowa. The breakneck pace of the tour was daunting; he would keep more than thirty engagements over the span of three months. Almost all of his stops were at universities with jaunts into the broader literary and entertainment culture off campus. Across the bay from UC Berkeley he mixed with Beat poets in San Francisco, led by Lawrence Ferlinghetti at their haven in City Lights Books, and near UCLA, he fell in with Hollywood film icons Shelley Winters and Charlie Chaplin. Winters not only knew of Thomas but was familiar with his poetry. When he amorously took her enthusiasm the wrong way, she successfully rebuffed his advances. Chaplin hosted him at his home and treated his group to an impromptu comedy routine. When the star-struck poet said his friends in Wales would never believe he had been the guest of Chaplin, his host delighted him by instantly composing a cable and sending it off to his wife Caitlin in Laugharne.7

This was no perfunctory set of visits, but a carefully plotted tour arranged by his literary agent Brinnin to maximize Thomas’s exposure and generate employment opportunities. What brought Thomas to Iowa was a combination of the sheer scale of Brinnin’s colossal publicity network, fueling the literary equivalent of the Beatles’ American invasion, and Engle’s extraordinary capacity to attract the most significant writers of the era. Robert Lowell’s presence on the faculty was the key to securing the date with Thomas, who had admired his poetry and sought a similar position to his at an American university as a means of continuing his career as a practicing poet. A key shift in Engle’s responsibilities for the Workshop had led to his hiring of Lowell. When Ray West brought his journal the Western Review with him to Iowa, Engle’s editorial duties ceased. West’s Review lifted Engle’s burden of running a new journal after American Prefaces had discontinued publication during the war years. This enabled Engle to concentrate his energy and time on expanding his network, which rapidly grew to include “every American and British writer of any accomplishment in the last sixty years,” many of whom Engle brought to Iowa as faculty, both temporary and long-term, or students.8 In a 1976 letter, West recalled that Engle was in New York soliciting funding for the program during Thomas’s visit, noting that the “teachers of poetry during Paul’s absence were Robert Lowell and John Berryman” and that the “Visitors who came to read and lecture included, most memorably, Dylan Thomas and Roy Campbell.”9

Lowell, thinking like Engle, knew that Thomas’s presence on campus would infuse the program with fresh energy. West had recently heard word that Thomas was nursing a horrific hangover after his Notre Dame engagement, when “the boys in Chicago had been feeding him boilermakers.” Advised to restrict hard liquor and “keep him on beer,” since “he loves beer and gets along well on it,” West heard opposite advice from Lowell, who knew what kind of impact an unleashed Dylan Thomas could have on the campus community. With no limits to his behavior, Thomas might “be provoked into creating some scandalous fuss that would enliven the city,” a comment revealing how little Lowell cared for the visitor’s personal well-being in the process of exploiting his popularity for the Workshop’s benefit. Thomas’s stay with West extended to just under two weeks before he boarded a flight from Cedar Rapids to San Francisco to continue his tour.10

Since Thomas emulated Lowell and desired a position like his at Iowa, he knew that remaining as long as possible beyond the requisite night or two might pay dividends toward a future faculty job. In the wake of the tour, he entered negotiations for a position with the speech department at the University of California, Berkeley, despite his failure to comprehend the unit’s purpose and self-definition. “I don’t quite know what the function of this department is,” he confessed, undeterred in his pursuit of an offer. “No date for my possible employment was mentioned, but I gather that it is under discussion now,” he wrote a friend in hopeful tones.11 During the planning of the tour, Thomas made his immediate short-term demands clear: “I don’t want to work my head off, but, on the other hand, I do want to return to England with some dollars in my pocket.” Aware of his own inability to handle money and perennial confusion about the location and time of his appointments, he gratefully handed over such matters to Brinnin: “I’ll have to leave this to you. I hand the baby over, with bewildered gratitude.”12

After returning from his trip, he wrote his wealthy patron Margaret Taylor about the position of poets in universities. On display in the letter is Thomas’s capacity to play the mad poet persona on the page and not just in person. In it, he dramatizes his exhilarating and exhausting tour that kept him from his correspondence. “I was floored by my florid and stentorious spouting of verses to thousands of young pieces whose minds, at least, were virgin territory,” he quipped with a clever double-entendre. Delighting in the sound of his rollicking recollection, he continued, “I was giddy agog from the slurred bibble babble, over cocktails bold enough to snap one’s braces, of academic alcoholics anything but anonymous.” In Iowa City, he was escorted in “powerful cars at seventy miles an hour,” rocket-like speed for the time, “tearing from Joe’s Place to Mick’s Stakery, from party to party.”13 The letter then abruptly pivots as Thomas dons his poised and calculating alter ego, an identity acutely aware of the institutional parameters of making a living as a professional poet.

In sober exacting prose clashing with the madcap debauchery of the letter’s opening two paragraphs, Thomas measures the landscape of professional positions for poets, paying close attention to the role of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. The shift suggests Thomas’s use of the mad poet role was a gratuitous act for Taylor’s amusement, a way of charming her before focusing on business. Now surveying his competition with deadly accuracy, he identifies the only well-known poets unattached to universities, “Wallace Stevens, Vice President of an Insurance company, and e. e. cummings, President, Treasurer, Secretary, & all the shareholders of E. E. Cummings Ltd, a company that exports large chunks of E. E. Cummings to a reluctant public,” he observed with a jab at his rival. But Robert Lowell’s career, he makes clear, is exemplary of the potential for a poet’s professionalization in conjunction with American academic institutions in 1950. With great precision, he defines Lowell’s position as “running a Poetry Workshop in Iowa State University [before it was renamed the University of Iowa], there to ‘discuss the demands of the craft, to criticize the individual works of student members of the workshop, and to foster enthusiasm for poetry & the sense of criticism among them.’ ” He notes Lowell’s official title is “Poet in Residence” and that another writer runs a similar workshop only for prose. “Lowell is paid the same salary as an Assistant Professor: in his case, between 5 & 6,000 a year.” The advantages to such a position are obvious compared with the dearth of such professional opportunities for poets in Great Britain. “The disparity in incomes, & in spending power, between America & here is so great,” he noted, that one can only imagine “what money a similar post, if established here, would demand.”14

Taylor had considered providing funds for the establishment of a program in creative writing like Iowa’s at a British university, naming Thomas as faculty and perhaps director. The thoroughness and accuracy of his description of the various institutional arrangements for the employment of practicing poets at American universities suggest Thomas’s serious desire for such a position. He specifically comments on programs for whom “the procedure is the same as in Iowa” in which “the Poet in Residence is engaged for one year only,” comparing them to others. He described “other universities [where] the Poet is engaged for far longer periods, sometimes permanently.” The variance of time frames also pointed to the possibilities “to arrange for other poets to come along occasionally as guests, & supervise the activities of the workshop (if it could be called that) for one session or more and/or to read or lecture.”15 Taylor demurred on that prospect, but maintained her support of Thomas by purchasing a basement flat for him and his wife Caitlin in London, under the assumption that it would place him in a more favorable position from which to search for employment. The couple moved in winter of 1951, but Thomas detested the accommodations, calling it his “London house of horror,” and did not return after his second trip to the United States in 1952.16

Thomas’s admiration of American university positions for poets was of course complicated by his disdain for criticism. The day after his reading in the Senate Chamber of the Old Capitol at Iowa, Lowell introduced Thomas to thirty-five MFA students in one of the Workshop’s converted army barracks. Thomas, totally uncomfortable in the classroom environment, especially in the instructor’s role if only as a guest speaker, was bewildered. He asked Lowell sheepishly after his lavish introduction what he was supposed to do. Lowell, barely concealing his frustration, “waved his arms in the air. ‘Anything,’ he said, ‘just anything,’ ” West recalled. “Dylan explained that he was no critic, he didn’t really know how to talk about poetry, the way critics did.”17 Instead, he asked Lowell for an anthology of British poetry, which he handed him. Thomas, suddenly comfortable and animated, leafed through the pages to the poems that he liked, read them with the same dramatic virtuoso flair of his performance the day earlier, and paused to explain why they appealed to him. He also made mention of poems he disliked and offered explanations for each. The critic in him emerged. Had he lived longer, he might have found his voice as a powerful instructor in an MFA poetry workshop like Iowa’s.

Thomas’s admiration of university poets helps explain why he was relatively well behaved on his trip to Iowa City. As his correspondence indicates, he was on a mission to establish a professional career in the manner of his friend Robert Lowell. The unusually long time he spent at the Workshop, and willingness to make a return visit, point to the value of Iowa in his estimation. He left a lasting impression and was long remembered mainly for the poetry, if not for a few slips triggered by whisky. On one occasion, he succumbed at Joe’s Place in Iowa City, missing a dinner engagement and returning home to West’s residence early the next morning. A woman had taken him to her apartment on the opposite bank of the Iowa River where she kept his glass full of Scotch all evening while reading from her own poetry. Thomas tolerated the abysmal poetry in exchange for Scotch, so he stayed, missing his dinner date and alarming the Wests, who did not hear him stagger onto their porch until long after sunrise. On another occasion, a discussion with a doctor’s wife over martinis turned ugly. The conversation moved toward socialized health care, of which he was a staunch proponent, having benefited from it personally. “Why, you don’t know what you’re talking about!” she screamed at one point when she perceived one of his comments as an insult to her husband’s profession. He shot back reflexively, “You bloody fuckin’ bitch!” The phrase was a mere preface to what West described as “the most elegantly strung together sequence of obscenities she had ever heard uttered,” profane poetry at its best, liquor-ridden misogyny at its worst.18 If these were his most scandalous scrapes in Iowa City, he had behaved like an angel, especially compared with the ugly public battles—some devolving into embarrassing drunken tirades—with his wife Caitlin in San Francisco two years later.

Before he could make a concerted effort at securing a university position, Thomas died at the age of thirty-nine, on November 9, 1953, in a Catholic hospital in Manhattan just days after claiming, “I’ve had 18 straight whiskies. I think that’s a record!”19 Multiple complications—gout, upper respiratory infection, and several other untreated conditions—have been disputed since as the causes of death. Pathologists conducting the autopsy claimed that pneumonia, brain swelling, and a fatty liver were also contributing factors. He had complained of difficulty breathing and was rushed to the hospital, slipping into a coma for several days while doctors worked to revive him. Although Thomas himself was unconscious, his wife Caitlin was the one “raging at the light” in accord with his most famous poem. She arrived at the hospital “stinking drunk,” asking, “is the bloody man dead yet?” Complicating matters was the presence of Thomas’s mistress, Liz Reitell, at the hospital. Deepening tensions further, Reitell was the assistant to John Malcolm Brinnin, Thomas’s literary agent, who was also at his bedside.

Finding her husband in an oxygen tent attached to a respirator with a tangle of intravenous tubes protruding from both arms, Caitlin mournfully pressed her body against his. But in her drunkenness, she neglected to notice the effect of her weight on his lungs. His already labored breathing slowed dangerously, alarming his nurse, who intervened and banished her to an adjacent room. There she waited with Brinnin, whom she blamed for Thomas’s suffering, since he had concocted the slate of professional engagements and projects that eventually overwhelmed the poet. Brinnin foolishly responded by attempting to calm her with whiskey. Becoming increasingly agitated, she flew into a rage and began smashing her head against a window, which would have shattered if it had not been reinforced with mesh wiring. Medical personnel descended on her, and Brinnin backed away. Turning her roiling emotions on them, she ripped a large decorative cross from the wall of the Catholic hospital and swung it fiercely, first at Brinnin and then at the orderly. Now completely unhinged, she wheeled with the crucifix gripped in her hands like a baseball bat, shattering a statue of the Virgin Mary before the orderly could wrestle her to the ground, blood filling her mouth and flowing from his hand where she had ground her teeth. Once Caitlin was safely removed from the scene in a straitjacket and rushed to a psychiatric unit, Thomas’s mistress, Liz Reitell, whose presence Caitlin was unaware of, quietly crept back to his bedside where she resumed her vigil beside the wheezing patient.20 Amazingly, Reitell had managed to avoid the entire frothing melee—a violent blasphemy in this otherwise somber Catholic setting—without a scratch.

Caitlin’s attack on Brinnin was motivated by her contention that the agent was overzealous and that the promotional engine responsible for building Thomas up had instead torn him down. Interestingly, among all the promoters of literary talent at the time, no one was more acutely aware of Thomas’s star power than Engle. The lasting effects of Thomas’s visit on the Workshop were visible more than a decade after he tore through Iowa City like a cyclone. Workshop graduate Edmund Skellings, for example, was acutely aware that the oratorical brilliance of Thomas had elevated his celebrity status to rock star proportions. He thus launched his own tour of American universities as “the American Dylan Thomas,” according to the caption of a giant poster of the poet leaning earnestly into a microphone, striking the unmistakable pose of a charismatic lead singer of a band. Along with the poster, the standard packet of promotional materials advertising Skellings’s “Electric Poetry” tour included copies of a descriptive pamphlet bearing Engle’s blurb from the Miami Herald in bold letters at the top, heralding the act as “A new direction for poetry itself.” Through Engle’s marketing connections with the commercial advertising industry, and with Thomas as inspiration, Workshop talent was clearly being packaged and sold as show business. “Edmund Skellings calls his unique performance ‘lyric theatre,’ and one critic has called it ‘spoken singing,’ ” according to the pamphlet. “But whatever one names it, this complex blend of rock and rhyme, humor, blues and psychedelics is a totally fresh exploration of how meaning happens in mind and mouth,” it continued, leaving no movement in popular contemporary music unmentioned. Marketed as “acted poetry with original lyrics in the conventional beat patterns of popular song,” Skellings’s show was performed in scenes drawing from the tradition of live theater. A small vinyl 45-sized record under the label “Professional Associates Dania, Florida” is folded in with the poster and flyers with a playlist of his numbers, “Testing, The Lecture, Down in the Ghetto, Nowno.”21

Thomas’s impact on mass culture has not been replicated since, notwithstanding the efforts of Skellings, the self-described “American Dylan Thomas.” Based on his Collected Poems, 1934–1952, Thomas was arguably the era’s greatest living poet, perhaps best known for his lyrical masterpiece, “Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night,” a poem that eerily foreshadowed his own passing. “Rage, rage against the dying of the light” is directly addressed to his father but also functions as Thomas’s vow to live out his final days in bold defiance. Indeed, “Wild men who caught and sang the sun in flight” is a prophetic self-description.22 With the radio drama Under Milk Wood, which was later produced as a play, under way in New York City, Thomas died soaring at the height of his powers. By 1952, critics generally agreed with the proclamation by Philip Toynbee of the Observer declaring him “the greatest living poet in the English language.”23

The Passing of the Torch

When it came to defending the memory of Dylan Thomas no one was more ferocious than poetry Workshop faculty member John Berryman. In fall of 1953, Lowell had been kind enough to allow several literati from Iowa City who were not enrolled students to attend his seminar. These impeccably dressed urbane amateurs regarded verse as an affectation or fine verbal ornament to life, vestiges of the rhymer clubs and literary cliques of the nineteenth century who typically churned out third-rate poetry to be read at their own group events with no ambition for publication or professionalization. Many were fans of Lowell’s and were avid readers of Lord Weary’s Castle. (Berryman’s own accolades would mount in the coming years, reaching a zenith with a National Book Award in 1969 for His Toy, His Dream, His Rest.) Lowell had invited these dilettantes to class in part because they could always be counted on to praise his work and lend credibility to his status. So when they appeared in Berryman’s class the following semester, in the winter of 1954, showing themselves as Lowell groupies by clutching their well-thumbed copies of Lord Weary’s Castle to their chests, they faced less welcoming circumstances.

The poetry these affluent citizens wrote stayed within their own circle and thus uniformly received a self-congratulatory reception. Lowell only occasionally asked his non-enrolled followers to submit their work for the class’s criticism, which was politely vapid, much like the poetry itself, as Philip Levine recalled. When Berryman demanded a poem from one of the group, the poet received a brutal initiation into the workshop method. Berryman began politely enough, reading the poem, which commemorated the late Dylan Thomas, and asking the class for feedback. When he heard nothing, he delivered his own, refusing to treat the poem with kid gloves. Incensed, he lit into the piece. “No, no,” he said shaking his head violently, “it’s not that it’s not poetry. I wasn’t expecting poetry,” reflexively insulting the writer. A deeper moral principle had been violated, one that bore directly on the memory of the revered Thomas, whose manner of death might present the subject of a moving elegy in the right hands, but to Berryman was not to be treated with fictional flights of fancy. In this case, the poet had cast the doctors as the villains for losing Thomas, because they had subordinated his well-being to their own financial profit. Berryman, who had been extremely close to Thomas, raged at this conceit, charging, “it’s not true, absolutely untrue, unobserved, the cheapest twaddle.”24

Poets, of course, have artistic license just as fiction writers do, to recreate and recast events to evoke deeper truths otherwise hidden by strict adherence to the objective reportorial facts. Anne Sexton—who attended John Holmes’s poetry workshop at the Boston Center for Adult Education with Robert Lowell (the two drove together and parked in the loading zone in honor of their ritual visit to the bars after each session)—was one of many poets adamant that the “confessional school” of poetry, which she had helped establish along with Snodgrass’s aching portrayal of his separation from his daughter in Heart’s Needle, had such latitude. “Unknown Girl in the Maternity Ward,” she insisted, was not autobiographical; instead it featured a created dramatic identity as its voice and central figure. But Berryman, since the writing in this case was so far below qualifying as poetry, and since it so grossly solicited the memory of Thomas as an object of sentimentality, felt he was in the presence of an intolerable lie that threatened nothing less than the historical memory of Dylan and his generation of great poets.

He went on with his diatribe to set the record straight, emphasizing that the doctors who worked on Thomas “did not work for money.” Although he did allow that the medical personnel “did not know who the man was, that he was a remarkable spirit,” he insisted that their humanity drove them because “They knew only that he was too young to die, and so they worked to save him, and, failing, wept,” as Levine observed.25 Although Berryman did not name Thomas during his rant, Levine later confirmed him as the tragic figure of the poem who was too young to die. What drove Berryman into a tirade was the thought of Thomas being made a spectacle for the sake of saccharine third-rate poetry written by non-enrolled Lowell fans. Berryman, however, missed the poem’s indictment of the American medical industry, operating according to a free market model in which doctors are rewarded financially for their work. The underlying assertion of the piece, hidden from Berryman’s perspective, was that under the socialized medical care of Thomas’s native Wales, with its presumably more compassionate doctors driven to serve humanity for its own sake, the poet might have survived. As seen by Thomas’s own fierce defense of socialized medicine earlier with the doctor’s wife, the topic was prominent in the culture, and he harbored passionate convictions about it. So it was a fashionable subject to superimpose on the circumstance of Thomas’s death, but it became intolerably pretentious in the poem when overlaid with dripping sentimentality. Berryman’s diatribe dispatched the guilty party, visibly shaken, from the room. Emotion pouring through him—the thought of such mistreatment of Thomas’s memory in the popular mind struck him as profoundly toxic—Berryman was not able to continue, and thus dismissed the rest of the silent and stunned class.

The exclusivity of the program was never so bluntly applied as under Berryman’s direction. This points to the changing climate at Iowa from its early days of communal cohesion, as recalled by Robert Penn Warren. The spring of 1941, the “most protracted” of his visits in Iowa City, was a time notable for “the pervasive and communal literary sense . . . the interpenetration of interests among faculty (or a number of faculty) and students.” He was struck by “how people of basically different interests and trainings could find a common ground, fruitful for all. I am sure most of those people never had found anything like that before or ever since,” Warren remarked, politely qualifying his praise in his next comment. “It is only natural that I should, over the years, have wondered if this atmosphere could survive the great public success and enormous size of the school.”26

Frances Jackson, a disgruntled Workshop alumna, recalled a different culture in the next generation, which she believed suffered because “The workshop is just too big.” Citing competition among students for valuable funding and fellowships, and the unjust system of playing favorites, she complained: “Those with financial aid are always in the limelight, are in ‘The Hall’ all day, meet the faculty, become friends with them,” a scenario that put them on the inside track toward long- and short-term financial gain. “Then when it comes time for teaching jobs, more fellowships, grants, awards, etc. they are naturally the ones who get them,” she observed, her frustration with her own stalled career apparent. “Iowa can do a whole lot for the chosen few. In fact, because it is so large” (at the time, enrollment reached sixty), “I don’t think it can do as much for the average student.” In this urbane and elite culture, “To be a dominant figure at Iowa it would also help to be an articulate, intellectual, verbal person from New York City. . . . No one would ever guess it was in the Midwest by the tone that is set by New Yorkers. They are witty and verbally flashy and others dim by comparison.”27

Of course this clashes with Warren’s utopic portrait of the program as a rustic idyll. He loved the sense of community at the time of his visit, mainly because he was already a full-blown literary celebrity when he arrived, and thus had students and faculty fawning over him. In his view, the program was intimate, but he also worried it had grown too large for its own good. Despite such a liability, he alluded to how “the record of achievement stands to be read” in the proliferation of student and faculty publications as testimony to the program’s success. Berryman and Lowell, essentially running the Workshop in Engle’s absence on a fund-raising trip to the East Coast, represented a key transition toward the cosmopolitan character of the program, and its status as a clearinghouse of dominant literary minds largely transplanted from more diverse urban locations.

Thomas’s visit to Iowa City and Berryman’s subsequent defense of his memory were watershed moments reflecting the increasing cosmopolitan sophistication of the Workshop culture. Like Thomas, Berryman came to Iowa when his career was on the rise, but his personal life was in shambles. Thomas’s death had raised demons for Berryman that he grappled with his entire life. They were perhaps never more visible than during his semester teaching at the Workshop, in the winter of 1954, just one year after Thomas’s death. Berryman had been undergoing psychotherapy for six years before his arrival in Iowa City, a time of protracted anguish he was happy to escape through full immersion in the world of poetry on the remote Iowa prairie. He originally underwent the treatment, a battery of orthodox Freudian sessions of the “talking cure,” to appease his wife after she discovered he was having an affair. The affair foreshadowed his second marriage, more than ten years later, to a woman twenty-five years his junior. These personal circumstances mitigated Berryman’s professional life. Professionally, he was developing from a well-known to a world-class poet while tasting the personal liberation of psychological and geographical distance from his disastrous marriage.

Berryman’s fierce stand on behalf of Thomas at the poetry Workshop was a testimonial to the life of arguably the greatest poet of the postwar generation, a fiery validation of the poet’s memory bearing the standard of excellence and seriousness, which Lowell’s followers pretentiously believed they could dabble in. Poets and poetry mattered more than mere diversion, and the project of producing professionals would be a demanding endeavor only for the fully committed. Further, Berryman’s deep sense of identification with Thomas derived from the uncanny similarity of their dual personae, of the public professional poet and the private romantic wild man. Berryman carried the torch of the mad poet in Iowa City, as his life there pivoted between brilliant, uncompromising teaching and savage altercations with both faculty and students alike.

“Lowell left in January and Berryman came,” as the future poet laureate Levine identified the spark that ignited his career. “Jesus, did the whole thing tone up. I was working well and hard, and he—though he was tough on me—was very encouraging.”28 Levine was not always comfortable with Berryman’s methods, however. He remembered “Berryman being tough on one of my poems, a poem that showed I was growing, though not a very good poem.” Then “Don Petersen came to my defense, making the point that the poem was evidence of real talent and lots of hard work and development, and that’s what should have been said FIRST. Then rip it apart for what was wrong.”29 Berryman notoriously lacked such tact. A violent verbal altercation he had with Marguerite Young at a local bar ended with his arrest at his apartment, landing him in jail. Headlines in the papers the next day scandalized the university’s administration, prompting his immediate removal from the Workshop.

The High Ones Do Not Go Gentle

Berryman’s volatility at Iowa derived from the pain of losing “the high ones,” the great poetic minds of his generation who “die, die. They die,” as he wrote in The Dream Songs.30 Homage and elegy were sacred and fiery forms to him at the time, informing his vitriolic rejection of the Lowell follower’s poem on the death of Dylan Thomas. Thomas’s reinvention of the elegy as a modern poetic form appealed to Berryman, who worked his entire career to master the art of homage in his own writing. Berryman reserved special admiration for Thomas’s “A Refusal to Mourn the Death, by Fire, of a Child in London,” proclaiming it “one of the profoundest elegies” written in English.31 The year of Thomas’s death, in 1953, Berryman had published his first major work, Homage to Mistress Bradstreet, which established him as a master of the elegiac lyric form. When asked in one interview why he wrote poetry, he said it was “For the dead whom thou didst love,” trusting that they will read it, “for they return as posterity,” citing a dialogue from Johann Georg Hamann quoted in Kier-kegaard.32 In Berryman’s hand, elegy was an eclectic and jagged concoction of grief, anger, and humor deeply influenced by the strange and moving music of Songs of Innocence and Experience by William Blake. Berryman was also an expert in Shakespeare, regularly demanding his students revisit specific plays in order to eradicate the palaver from their style. With the gruff confidence of a physician prescribing the perfect medicine, he told Levine on one occasion to reread Macbeth as a model for honing the technique and tone of his verse.

Berryman’s The Dream Songs, published in 1969, points to the concurrence of acute psychological turmoil and a surge of creative power that began to overwhelm him a decade earlier in Iowa. “Dream Song 36” is an elegy to William Faulkner, but derives from the mourning of Berryman’s own father, whose passing haunted him his entire life, and clearly foreshadowed his own death. Like his father, who died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound on Clear Water Island in 1926, Berryman also took his own life, forty-six years later. Only twelve at the time of his father’s suicide, Berryman turned the demons of this crushing tragedy into poetry. Unlike Anne Sexton, whose poetry enabled her to face her dark thoughts directly and exert some degree of emotional control over them, Berryman did not grapple with depression by aestheticizing the circumstances of his own death.

Berryman went in another direction with his darkness, focusing less on dialoging with the forces of suicide and instead on eulogizing the literary luminaries who were his contemporaries and, in several instances, close friends. Elegy in Berryman’s hands ran counter to maudlin mourning and sentimentality, for a richer pragmatic sensibility that he certainly shared with Sexton. Berryman’s poetic homage to Faulkner in “Dream Song 36” revealed the tragic self-immolation of the creative mind pervasive in a culture that believed “It’s better to burn out/ Than to fade away,” as expressed in the lyrics of Neil Young. Frost, Williams, and Eliot follow in “Dream Song 36,” which takes the shape of a poetic memorial to the great minds of his generation. He mourns the passing of Sylvia Plath, Theodore Roethke, and Louis MacNeice, a list that finally gives way to his personal intimates, Delmore Schwartz and Randall Jarrell, the latter of whom achieved fame for imagining his own demise in a World War II bomber aircraft in “The Death of the Ball Turret Gunner.” The gunner’s metaphorical birth is figured as an awakening “to black flack and the nightmare flares” that destroy him and lead to the cold, perfunctory processing of his remains. “When I died, they washed me out of the turret with a hose,” the voice reports from the afterlife with a knowing frankness about the hard coldness of the passage into death.

The poetic voice that speaks from the grave appears in the American tradition in Emily Dickinson’s equally bleak image of the passage from life to death in “I heard a fly buzz when I died.” Jarrell’s remains are unceremoniously hosed out of a turret and Dickinson’s senses abruptly shut down: “And then the windows failed—and then/ I could not see to see,” after their last perception is a random fly rather than a grand vision of the gates of heaven.33 A quiet rage—directed at the machine in Jarrell and at an indifferent deity in Dickinson—sounds a note of frustration and protest, at the cold inhumanity of the military-industrial complex in the former and the hollowness of conventional antebellum Congregational Christian dogma in the latter. Berryman similarly protests against the cosmic injustice of the disproportionately high numbers of brilliant poets that rank among the prematurely deceased.

During his darkest hours in Iowa, horrific visions of death menaced Berryman. Repeatedly awaking bolt upright in bed to a bombardment like Jarrell’s black flack and nightmare flares, Berryman struggled to ward off the demons. In a letter to his mother dated April 9, 1954, he described how he had “been suffering lately from terrible waking-nightmares and fear of death.” The bleak self-diagnosis pivoted on the fulcrum between a subconscious he could not control and the rational conscious life embodied by his identity as a professional poet and intensely dedicated faculty member of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop. To shape the uncontrollable demons into art was the challenge, a formidable one given the horror welling up from the trauma of his father’s suicide during his youth. The trauma was exacerbated in adulthood by watching his best friends and most admired poets pass before their times. Like William Blake, who turned his mad visions into the beautiful nightmares of his lyrics and visual art, Berryman buoyed himself on the conviction that “life is, all, transformation,” a phrase that appears in his letter to his mother with the resolve of a survivor.34 At times in The Dream Songs he marveled at his own capacity to endure: “I don’t see how Henry, pried/ Open for all the world to see survived,” figuring himself as the voice of Henry, described in the prologue as one who “has suffered an irreversible loss and talks about himself sometimes in the first person, sometimes in the third.” Asked once if he was Henry, Berryman acknowledged that he was indeed, noting however that his created poetic identity is free from the suffering of living: “Henry pays no income tax” and “Henry doesn’t have any bats” like the ones “that come over and stall in my hair.”35

Berryman’s dark humor, also notable in Blake, kept him afloat, even if it still left him rudderless. During one class at the Workshop, Berryman recited from memory Blake’s “Mad Song,” which skewers the condition of the romantic idealist. The poem reflects Berryman’s core aesthetic and self-effacing humor that enabled him to cope with life as mad poet. “I turn my back to the east/ From whence comforts have increased,” Blake writes, “For light doth seize my brain,/ With frantic pain.”36 The dark humor in the lines satirizes the singer’s self-imposed incarceration within the parameters of time and space and attempt to escape it by chasing after night. Berryman’s best moments in his own poetry similarly draw back from despair to mock it, not unlike Herman Melville, who routinely checked his own excesses through comic inversion, as when he skewers Ishmael’s romantic idealization of life aboard a whaler by placing him under the command of the mad Captain Ahab in Moby-Dick.

As with Sexton, poetry kept Berryman alive. One can see him rescue himself from despair within the poems themselves, as in “Dream Song 36.” Precisely when he is about to succumb to the dark notion of life as a curse to be endured while all the brilliant literary minds have died, his tone shifts. He adopts the vernacular and philosophy of a tough-minded and world-weary survivor, and quiet assurance prevails: “Now there you exaggerate, Sah. We hafta die./ That is our ’pointed task. Love & die.” Without the capacity to rally himself in the space of his poetry in this way, Berryman declined rapidly. In his last days, his depression and alcoholism finally interfered with his ability to write and perform at readings and lectures. Similarly, changes in Sexton’s pharmaceutical therapy—particularly her shift to Thorazine—intended to treat her depression only sapped her energy and dulled her creative edge. Without poetry, or more precisely with poetry in a severely compromised fog, she and Berryman had little to live for.

Had he remained at Iowa, a different John Berryman, both poet and man, would have surely emerged. Despite his complaints to his mother about the alienating environment—“I detest Iowa City,” he wrote—he qualified his otherwise damning impressions: “I don’t like the people here much, but have nothing against them.” The truth is that he was thriving at the Workshop in spite of himself: “Several of my students are good enough to be worth the trouble,” especially Philip Levine and Anita Phillips. Behind the mask of the disagreeable curmudgeon was his admission that “everyone [is] very pleasant” and that his work in the classroom was both painstaking and satisfying, a labor of love he deeply valued. He had spent a great deal of time “setting up my courses, at which I’ve worked very hard and am teaching beautifully,” an edifying yet exhausting enterprise that “has not left me much energy.”37

Such creative burning Berryman identified with the brilliant flare that was Dylan Thomas’s soaring Welsh-English voice, possessing a rhythm and wit of striking alacrity, tenderness, and verbal agility. The Workshop in Berryman’s seminar hardly drummed the individualism out of students or formalized their writing. Thomas’s meeting with students delighted in their diversity of voices and experiences; he would also be hard to imagine as a scold demanding regular meter. If Berryman had been harsh, it was only because “Even a class as remarkable as this one will produce terrible poems, and I am the one obliged to say so.”38 But what marked both mad poets was their openness and encouragement of young talent. As we saw, Lowell had discouraged Snodgrass on early drafts of Heart’s Needle, demeaning what others considered courageous self-disclosure and emotional verve in treating the subject of his separation from his daughter. “Snodgrass,” he groused, “you have a mind; you mustn’t write this tear-jerking stuff.”39 Berryman gave opposite advice, never condemning early drafts as sentimental, and always pushing the metrical and formal limits of his syntactical expression. Levine received such guidance from Berryman, who inspired experimentation and unusual subjects, which the more formally inclined Lowell detested, tending instead “toward poetry written in formal meters, rhymed, and hopefully involved with the grief of great families, either current suburban ones or those out of the great storehouse of America’s or Europe’s past,” as Levine described. Levine’s poetry would thrive under Berryman’s eclectic, inclusive approach, inviting and validating his poems on subjects from his working-class background in Detroit. But Berryman never neglected or ignored the use of formal meter as an object of experimentation itself. “He even had the boldness to suggest that contemporary voices could achieve themselves in so unfashionable and dated a form as the Petrarchan sonnet,” testifying to how “he was all over the place and seemed delighted with the variety we represented.”40

Just as Dylan Thomas did “not go gentle into that good night,” Berryman would himself be among “The high ones” who “die, die. They die.” These mad poets burned through Iowa City, forever changing the place, upsetting the belief that literary professionalism necessitated the production of uniform workshop verse. Instead of suppressing subjectivity and idiosyncratic individual perception, Berryman encouraged it in his classes, and Thomas embodied it in his madcap visit and virtuoso reading. Both undermined the common assumption that teachers like Lowell had standardized poetic form, when both Levine’s and Snodgrass’s training and publications suggest otherwise. Their work, like their mentor, did not fit the description of the Workshop’s production of the disciplinary “quintessential form of literary professionalism” responsible for generating “the academic poem of the 1950s and early 1960s,” a species of writing “densely textured, tonally restrained, traditional in meter and form, replete with classical and mythological allusion and symbol.”41 In fact, Berryman’s aesthetic liberated his students to draw from traditional metrical forms and the rich symbolism of classical mythology—particularly according to the models of Shakespeare and Blake—to find a personal voice, like the ones Levine and Snodgrass discovered. His eclecticism indeed anticipated the Language writing movement of the 1970s that rose in opposition to the academic poem advanced by such writers as Lowell. In this manner, Berryman shared more with the Beats, as did Thomas. That aesthetic also demanded a full-bodied immersion in the creative process, one that left personal lives in ashes. Berryman and Thomas, whose madness was their poetry, embodied Jack Kerouac’s “mad ones, the ones who are mad to live, mad to talk, mad to be saved, desirous of everything at the same time, the ones that never yawn or say a commonplace thing, but burn, burn, burn like the fabulous yellow roman candles exploding like spiders across the stars.”42

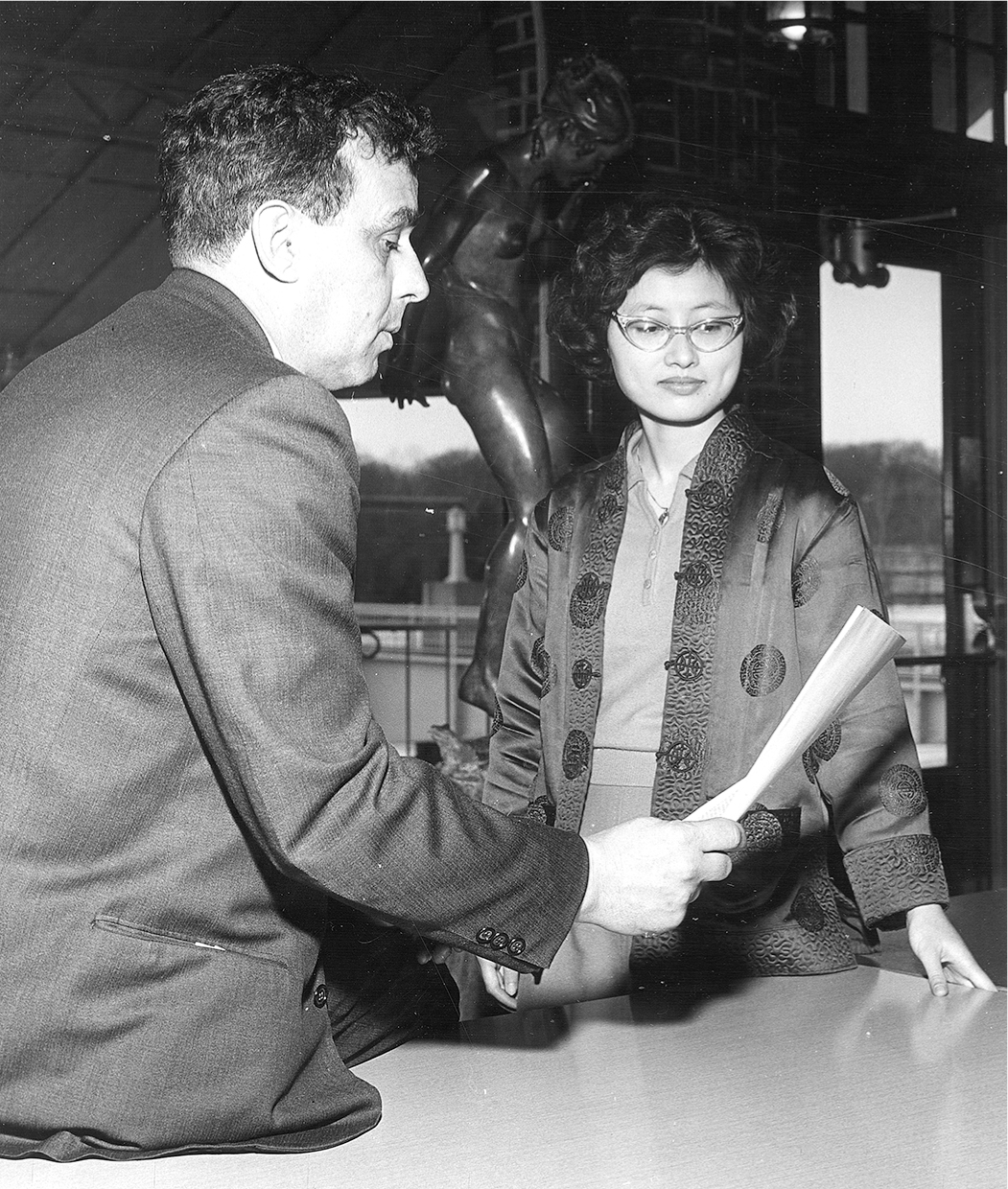

Flannery O’Connor at Amana Colonies, with Robie Macauley (with camera) and Arthur Koestler, 1947 (Wikimedia Commons)

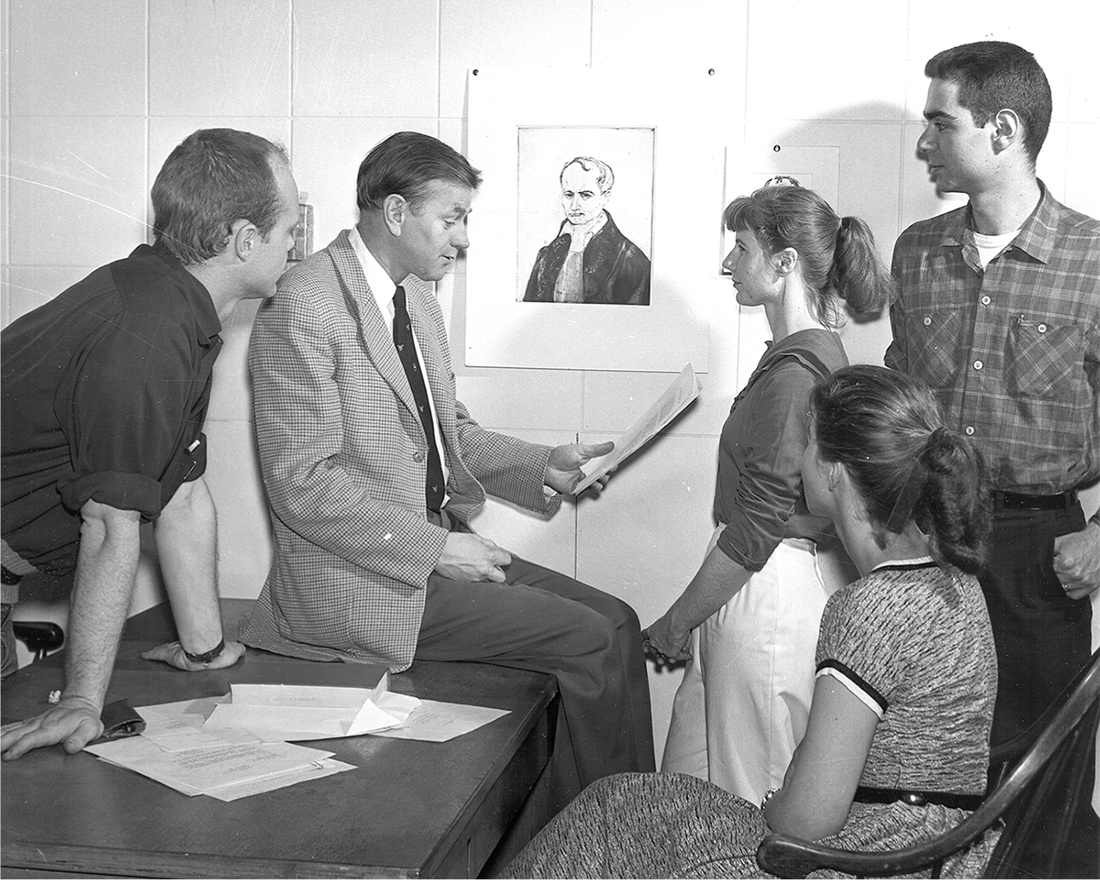

R. V. Cassill with a student at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, 1960 (Courtesy of the University of Iowa Library Archives)

Pulp fiction by R. V. Cassill, 1954: one of many attempts to supplement his income (Wikimedia Commons)

Paul Engle with Iowa Writers’ Workshop students, circa 1950s (Courtesy of the University of Iowa Library Archives)

Paul Engle (left), with Ralph Ellison, Mark Harris, Dwight Macdonald, Arnold Gingrich (standing), and Norman Mailer, at the Writer in Mass Culture symposium (sponsored by Esquire) at the University of Iowa, December 4, 1959 (Courtesy of the University of Iowa Library Archives)

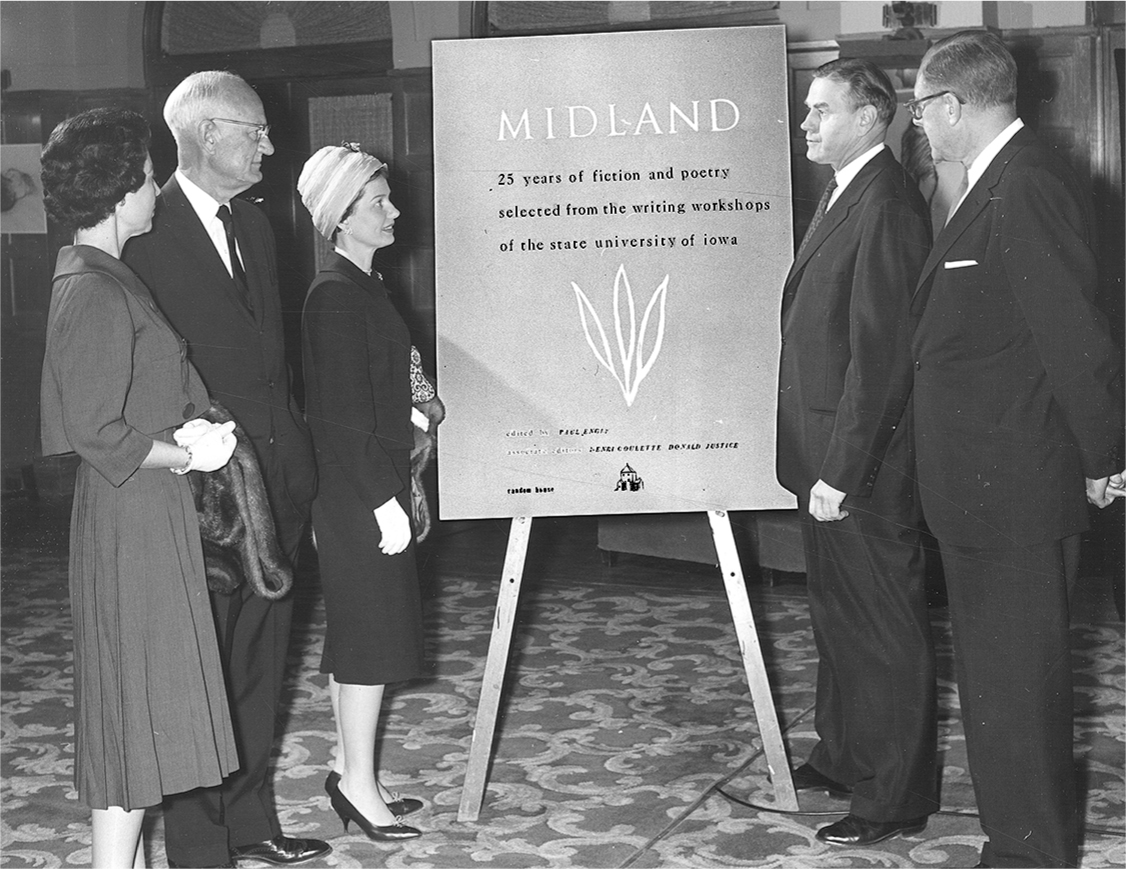

Paul Engle (right), presenting Midland: Twenty-Five Years of Fiction and Poetry, Selected from the Writing Workshops of the State University of Iowa (1961) to President Virgil Hancher at the University of Iowa, May 11, 1961 (Courtesy of the University of Iowa Library Archives)

Paul Engle at a reception for the anthology Midland, Iowa Memorial Union, University of Iowa, 1961 (Courtesy of the University of Iowa Library Archives)

Peace March in protest of the Vietnam War, Clinton Street, Iowa City, 1960s (Courtesy of the University of Iowa Library Archives)

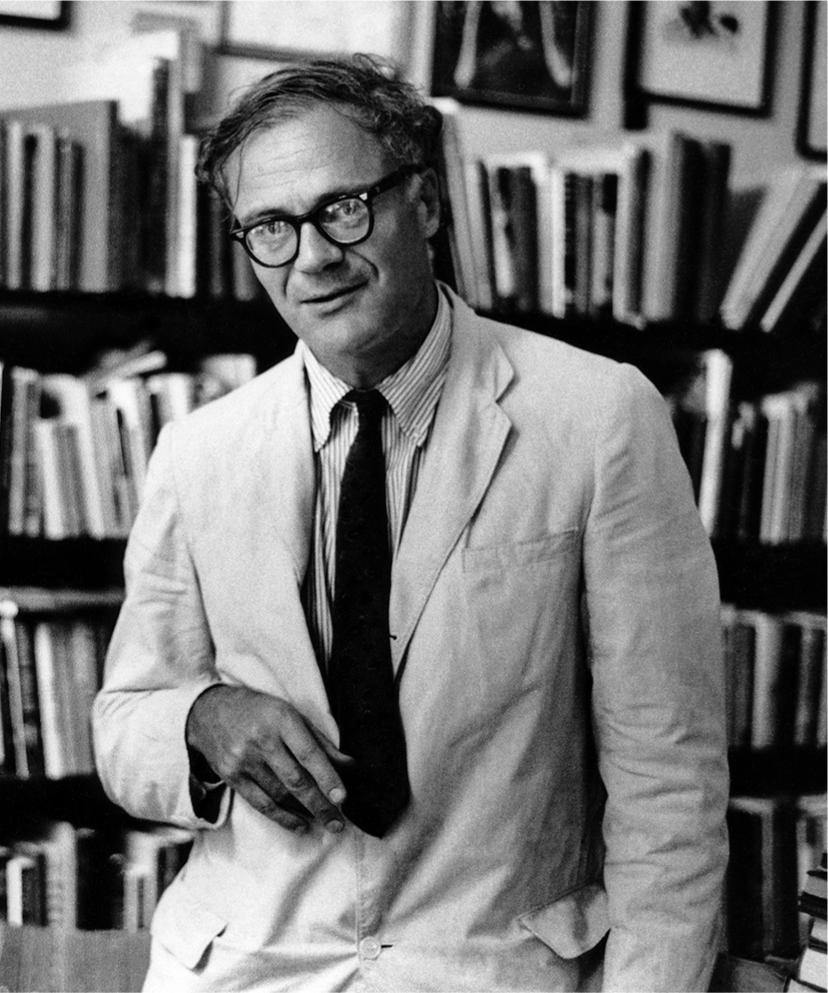

Robert Lowell, above, January 1, 1965 (Photo by Elsa Dorfman; Wikimedia Commons)

Kurt Vonnegut, left, February 17, 1972 (Wikimedia Commons)

Margaret Walker, Poetry MFA 1942, the first African-American graduate of the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, returned to Iowa to train as a fiction writer under R. V. Cassill. Jubilee, her doctoral thesis from 1966, was published by Houghton Mifflin. (Courtesy of the University of Iowa Library Archives)

Jane Smiley, October 31, 2009 (Wikimedia Commons)

T. C. Boyle, May 19, 2013 (Wikimedia Commons)

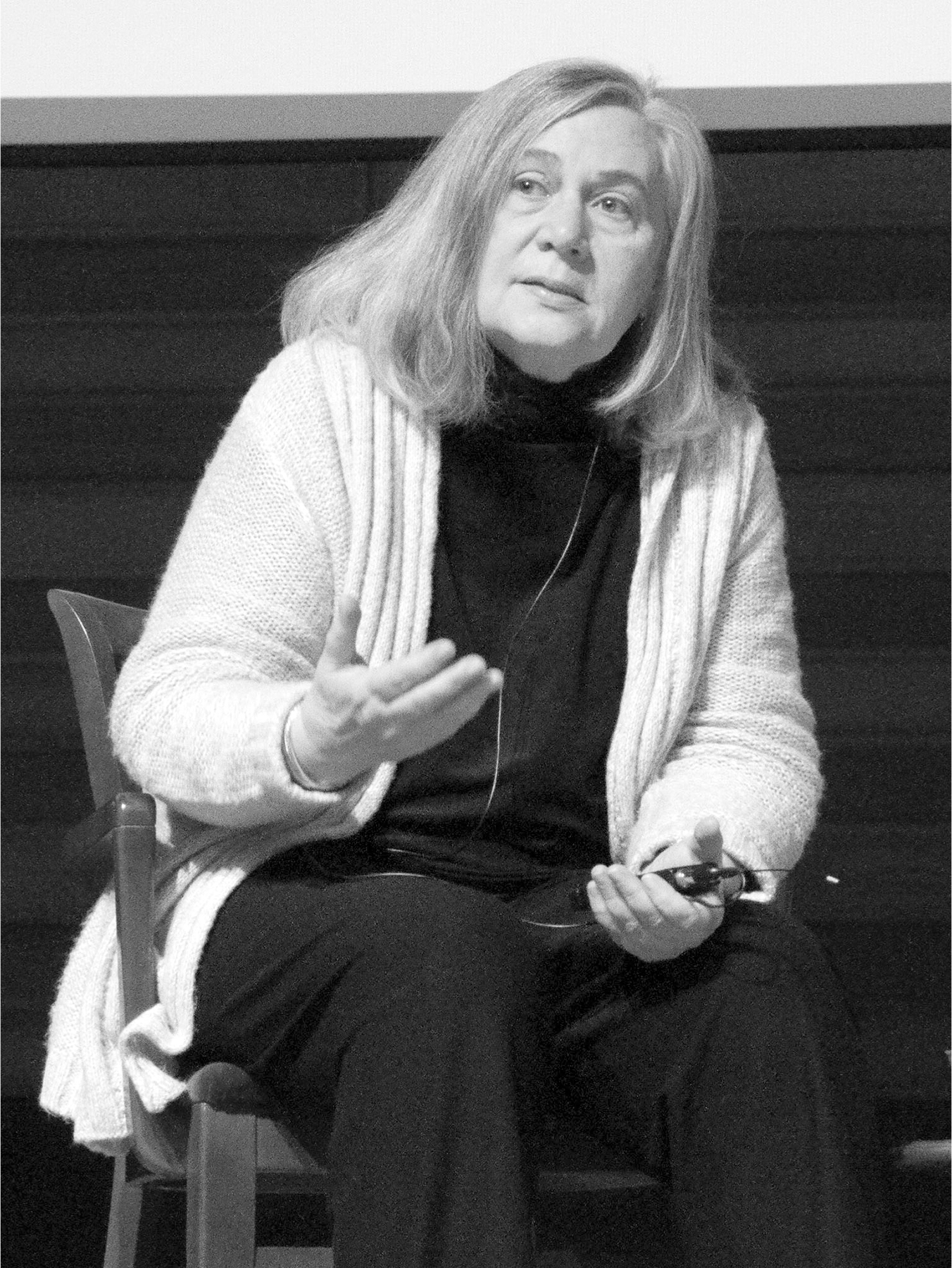

Marilynne Robinson, April 21, 2012 (Wikimedia Commons)