CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

Success on Nanga Parbat

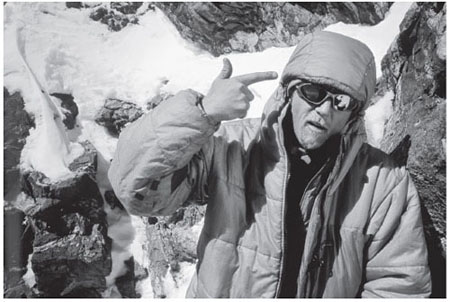

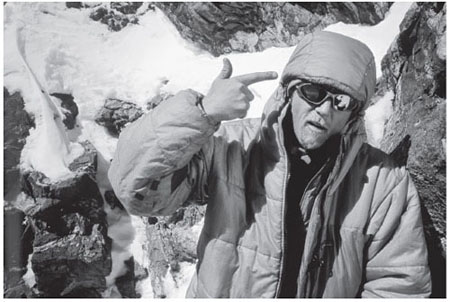

It’s good when your partner is still able to make a joke, even at 25,000 feet. STEVE HOUSE

Rupal Face Descent – 24,000 Feet on Nanga Parbat, Pakistan: September 7, 2005, 10 am

We’re late. Vince coils the ropes as I wiggle a pencil eraser-sized brass nut into a split in the greasy gray rock. When the sun hit the tent I woke and started the stove. I kept falling asleep while it ran but eventually we had one quart of water to wash down our breakfast of one GU each, and another quart to take with us. We struck the tent and packed what we have left: a couple more GUs, a singleserving packet of dehydrated bean soup, and one almost full fuel canister.

Now at 10 am, we’re just leaving camp. My limbs are thick and heavy. My brain is filled with altitude sludge and my thoughts won’t coalesce into words, just ill-defined impressions and feelings. One thought, however, is crystal clear: we need to get down off this mountain, now.

I clip our two ropes – now tied together to enable longer 165-foot rappels – into the single-point anchor and rig my rappel device as Vince tosses the ropes. I start backing up to the edge of the cliff. A thousand feet of rappelling should get us to the Merkyl Icefield. With a drag of my foot I push the last bit of rope over the edge when I suddenly drop, but manage to catch myself right at the edge.

“Whoa!” Vince shouts.

Instinctively I stand up as Vince leans forward to inspect the nut. “That’s not good,” he says.

“What.”

“Ahh. The nut shifted as you started. Give me the nuts, I’ll place a back-up.” Six rappels after Vince added the extra nut to the anchor the wide expanse of the Merkyl Icefield seems close. As I start the seventh rappel, I tell Vince, “I think that maybe we could just jump to it.” At the end of the ninth rappel we’re standing on the snowfield and Vince answers, “Guess we couldn’t have jumped for it.”

“Yeah, that was a long ways,” I agree. “We’d better be careful. I don’t think we’re thinking too well.” Vince nods and ties a loop in the end of one rope, clips it to his harness, and we start walking down together, Vince dragging the joined ropes.

“Now we’re on the 1970 route, the Messner route. Down here and just right of that snowy point we have to rappel down an ice cliff.” The directions I give are redundant. But they help us keep our bearings, reassuring us that we are returning to the world of the living.

“Right,” says Vince, as we walk side by side down the snowfield, coughing only occasionally, our crampons driving in a few reassuring inches with each step. Dropping over 1,000 feet has already made me feel better.

Rupal Face Ascent – 11,500 Feet on Nanga Parbat, Pakistan: September 1, 2005, 4 am

As I walk into the dimly lit mess tent, Vince, hidden in shadow, presses the play button on our little stereo. The opening stanzas of “The Ride of the Valkyries” blasts full volume into the darkness. Charging out of base camp at dawn, we climb unroped for 5,000 feet to our first bivy. Early in the afternoon we scoop snow off the lower lip of the bergschrund, pitch our two-pound tent and crawl inside to rest; safe from the accelerating whiz of falling stones and the relentless heat of the sun.

We wake at midnight to climb while the loose stones remain frozen to the mountain above us. I imagine millions of them perched above and across the massive wall, waiting for the sun’s rays to melt the thin layer of ice that holds them temporarily in place. Vince lashes a coiled rope under his pack lid as I start soloing across the steep slope above the bivy.

I traverse left, ice tools swinging easily, boots kicking effortlessly. I am gliding, buoyed by hope mixed with the ever-present fear of failure. I wonder about Vince. Though our friendship spans 10 years, we have not climbed more than a day route together. I am tense about having committed to an unknown partner. Flatland friendship is based on what we tell each other – much of it unverifiable. Each creates the image we want to project, who we think the other would want us to be.

The gully steepens; the ice is thinner than last year when I climbed these pitches with Bruce. Up here there is no hiding. Climbing partners can be as, or more, intimate than spouses. Over the next few days I will come to know Vince as few know him. Climbing big mountains exposes us. For this we must go, try, discover. After an hour of kicking and swinging, the ice ends in a small bowl of snow cut from the rock. I pull up against the left wall to a deep crack in the solid rock and build an anchor.

Vince steps up next to me and begins to rack for leading as I remove the rope from his pack and stack it carefully across my boots. Once tied in, he starts climbing, carrying the lead pack that, though small, still weighs 20 pounds. He reaches the base of the ice, stops, and places an ice screw. His headlamp casts a circular pool of white light around him.

As I watch him work, I am reassured by his attitude. His anxieties are correctly focused on things beyond our control – weather, rockfall – not on doubts about himself. “I don’t have the experience you have,” he told me when we spent several weeks climbing in Canada to test our compatibility for this venture, “but I can keep going for a really long time.” I thought that was a fine answer, finally, to the question I posed him that day at the Pool Wall in Ouray last January.

Vince hacks at the ice several times. “This ice is shit,” he says.

“Yeah? It was like that last year. I went up the right flow, even though it looks thinner, the ice was better.”

“Okay,” he replies. We’ve talked over these details a hundred times in the last months. I shared everything I learned about the Rupal Face on my attempt with Bruce; breaking it down into pieces so that Vince could digest what would be required each step of the way.

Our surroundings emerge as the sky slips from black to gray. Vince’s halo of light recedes before the pervasive soft light of early dawn. The details of the pitch become sharper and I see that the frozen cascade is more anemic than last year. Vince ascends to where the ice narrows and nearly disappears and the wall becomes vertical. I led this difficult and dangerous pitch last year. The ice was too soft to hold a screw, and the rock too broken to take good rock protection. Afterwards Bruce told me that only two of the pieces of gear would have held a leader fall.

Vince still has no gear in. I can hear him panting as he complains, “This pack. Ugh.” He sweeps away a few inches of dry, icy snow that sounds like millions of grains of broken glass tinkling down past my stance.

“Is that good?” I shout as he wiggles a cam into some unseen crack in the rock.

“It’s okay.” He takes the nuts off his rack and fiddles with three before one slots in. It makes a hollow rattle as he jerks sharply down on the nut to test it. With both pieces clipped he starts clearing the snice. He climbs a few tentative moves upwards, the pack pulling him off balance.

“God damn…Ugh. I’m coming down.”

“What?”

“I can’t lead this with the pack!” he yells. “I’m pumped!”

“Okay.” I lean back against my anchor to check the progress of the sunrise. We’re in the worst possible place for the warming of the day. Thousands of acres of potentially loose rocks are perched to fall down this ice gully we are climbing. From the top of this pitch we have three easier pitches – two of them we can solo if we really need the speed – before we’ll be safe from the rockfall.

I lower Vince to the belay and before he has clipped himself in, I grab the gear and rack up to try the pitch without the pack.

“Ready?” He nods and I’m off, inhaling as deeply as I can, I regain the two pieces he set.

“This gear sucks,” I say. “I can’t believe you lowered on that.”

“Maybe it shifted when I started down.”

“Maybe?” I reorient the cam so it seems a little stronger and continue climbing.

I approach an icicle the thickness of my arm that hangs down 10 feet from a black rock roof and pools into a flat plate of blue ice. I place a screw in the ice pool and thread a sling around the icicle, and clip both pieces into my rope.

“This is the hard part,” I think, remembering exactly which small fissure I cammed the pick of my ice hammer into 13 months ago.

“How is it?” Vince shouts up.

“Desperate!” I reply. I know that he understands that to mean that I love the tension, the effort, the climbing.

“Don’t rush,” I remind myself. Deliberately I torque a pick into the rock, test it with a tug, and step up on clear ice. Whrrrrr. The first rock sails overhead as the sun’s rays touch the upper wall. I press on my right toe and am about to reach up when the ice I’m standing on breaks and I swing against the wall. Very carefully, I reach out and press my crampon point onto a rock edge uncovered by the broken ice. I release the right tool with a gentle, slow wiggle and place it into ice up higher.

At the belay, I remember exactly which piece of gear went where. I tie in and start to haul the smaller pack while Vince prepares to follow.

“Climbing!”

“Okay!” I quickly tie off the pack and let it hang halfway up the frozen waterfall while Vince climbs. When he pauses to take out the first two pieces of gear, I start pulling the pack up hand-over-hand.

“Up rope,” Vince calls. I tie the pack back in and take up the slack in Vince’s belay. Five minutes later he arrives at the stance winded, the smaller pack still dangling below. While he ties himself in, I pull it up and put it on with the rope still tied to it.

“Belay me,” I say as I unclip, grab my tools and start climbing.

After I’ve gone 20 feet I hear Vince say, “You’re on.” At that moment a stone eggbeaters past me through the air.

“I’m going!” I find a pace just below my anaerobic threshold and hold it there: my chest is heaving and my legs pump steadily.

“Twenty feet!” Vince yells. I run out the rope, place an ice screw, clip it, and glance down. Vince has already started climbing. Wordlessly we motor toward the safety of the second bivy just a few hundred feet away.

Rupal Face Descent – 23,000 Feet on Nanga Parbat, Pakistan: September 7, 2005, 1:30 pm

Descending the Merkyl Icefield, we near the top of an ice cliff. An old, polypropylene three-strand rope appears out of the snow and angles down to the right. We follow it until it becomes too steep to walk. I turn in and front point down to where it is attached to an ice screw.

Vince stops and kneels, breathing heavily but more smoothly now. Still coughing, but with less pain in his face than before.

“What do ya say? Do we use this old screw?” I ask.

“Well. It is fixed. I don’t see why not.”

We’ve been independent of any outside help for seven days, and I’m not ready to start relying on others’ relics now.

“We don’t need it. I’m drilling a thread.” Vince waits patiently as a fog rolls over us in patches.

After the third rappel we can’t see 20 feet. Swallowing pride in the interest of expediency, I clip the next fixed ice screw I see. We need to go fast now, and the fastest thing is to use what’s available. I’m haunted by past minor transgressions such as accepting food and shelter from the NPS Rangers at the 14,200-foot camp after the Slovak Direct. The lack of visibility is unnerving, but the moist air feels luxurious on the ragged tissues of my throat. This time I rig our rappel from the fixed screw and it brings us to another snow slope which angles sharply to the right. I sit in the snow with my pack on as Vince comes down.

“What’s up?”

“I think this is near where Bruce and I joined the Messner route last year. And if I’m right then we need to be off to the left. The crest of the rib that the route follows is on the left.”

“Looks like it goes down to the right here.” Vince is skeptical.

“I know. But I think that leads to a really big ice cliff and we’d be screwed.”

I pause and Vince pulls the ropes. “Whatever you think. I’ll trust your judgment here.”

“I think to the left. If I’m right we should find more fixed crap: ropes, maybe some kind of anchors, within the next few hundred feet. The old Messner route Camp Three is nearby, if we find that we should bivy and hope for clearer weather in the morning.” I stand and start angling to the left.

I down climb facing in even though the climbing isn’t steep. The fog is disorienting: visibility is almost zero. It’s like climbing inside a cotton ball. No up, or down, no shadows. Just the reassuring feeling of my boots in the snow and my hands on my axes. I move down and across the slope.

I feel a subtle change in the slope angle. To get some depth perception, I scrape my foot across the snow surface, my eyes tracing the track to where it suddenly ends. I kick loose a block of snow and watch it roll twice and be swallowed in the cloud and snow and whiteness. I know the far side drops sharply away: I’m on the crest of the ridge.

“This is it!” I shout into the cold damp wall of wind. I don’t know if Vince can hear me. I can’t see him and he does not reply. Facing in I continue down, gliding my hand along the ridge crest like a banister. I ache. My legs move on autopilot as my mind molds the rhythm of the wind into the crescendo of a warm Gregorian chant. The pitch rises and falls, the tone deepens. I spot an abandoned piece of fixed rope that confirms we are on route.

Rupal Face Ascent – 17,770 Feet on Nanga Parbat, Pakistan: September 3, 2005, 3 am

Our second camp is safely above the greatest threat of rockfall, so we sleep late and don’t get up until 3 am. Soloing by headlamp, we each climb in our individual circles of cool, white light. We follow a small ridge and prepare to cross a dangerous avalanche path. Yesterday we watched tons of snow and ice, loosened by the sun, plummet down this gully. Any one of the avalanches would have crushed a small office building, not to mention a couple of puny climbers.

In the cold darkness the gully is quiet. I pause to listen as my breath slows and I prepare to sprint across to minimize my exposure. I look out to the vivid, warm orange edge of the earth, ragged with the teeth of the Karakoram Range to the north. K2’s great pyramid stands tall next to Broad Peak and all seven of the Gasherbrum peaks, Masherbrum and Chogolisa. The K7 and K6 groups frame a parade of subservient mountains marching east across the glowing Indian frontier.

I sprint just before the sun’s rays light up the summit 7,000 feet above. Vince watches me cross safely and starts his own ragged, vertical sprint. Once he’s joined me, I punch on ahead, searching for a sustainable rhythm. I’m distracted from the monotony by the pink light bathing the white ice wall to which we cling and the buttresses of dark stone checked through with bits of ice and mushrooms of snow.

The valley below remains shrouded in darkness; no cooking fires or lights of any kind are visible. We are already a vertical mile above the churning river, swimming upward in the sublime glow of dawn. I stop to take pictures of Vince coming up below. He grinds steadily upward, closing the gap between us as I scan the horizon. Much of the sky is filled with the mountain above, looking out I can see China and India and south to the Punjab plain of Pakistan.

The day grows warmer, and I am slowed by burning thighs; step, breathe, step, breathe. Gradually the ice steepens and becomes more strenuous until a rib of rock emerges. I climb up its right flank for 30 feet until I need the security of the rope to continue.

I balance on the rocky crest, standing on a small ledge and secure myself to a man-sized horn. I take the pack off. Vince arrives and I remove the rope from his pack and prepare the climbing gear. He clips off his pack, dumping it with a heavy sigh. Vince racks the gear onto his harness, and I flake the rope before handing him some energy gel and a water bag. He squirts the gel into his mouth and takes three large gulps.

He leads through a steep rock barrier to threads of ice gracefully formed by seeping patches of snow. Climbing great alpine walls is more about adventure than the quest for the “good” moves on solid rock that climbers rave about. But this pitch is fun. Under a bright-blue sky I edge my crampons on small wrinkles in refreshingly hard stone, following Vince up the delicate smears of ice.

As Vince leads pitch after pitch, puffs of cloud form against the wall. The climbing is moderate, but hard enough to keep the rope on. He leads a full 165-foot-rope length, places an ice screw, clips the rope in, and we climb together in running-belay fashion. He can do this for five rope lengths because we have five ice screws. I try to do the calculations in my head between steps. “Five times one-sixty-five. Okay five times five is twenty-five, five times sixty is three hundred. Eight hundred and twenty-five feet of climbing between leader changes.”

I start my second five-rope lengths of leads – my 825 – as clouds build around us. Between steps my mind wanders. “The end of this block will put us at thirty-three hundred feet of climbing so far today. Is my math right?” And I start again. “Five times five is twenty-five…”

It’s dark by the time I finish the fifth pitch. At the anchor Vince gnaws on a half-frozen Snickers bar. My calves burned up, then felt fine, then the burning came on again. So many cycles of pain and relief that I can’t remember. Vince is climbing at a snail’s pace. I hurt, that I know.

“We’ve gotta bivy,” Vince says as he struggles to cross the last 10 feet to my next belay stance. “I’m wasted.”

“Me too. I think we have to go up a bit more and then right. We should get onto that hanging glacier. I just hope we can find an easy bivy.”

“No shit!” as he drills his ice tool home with a grunt.

I put my headlamp on over my helmet. It’s about to get dark and we’ve been climbing without more than a few moments rest for 16 hours. “Your lead. You want it?”

“I don’t think so.”

“Okay.” I’ve done this before, kept climbing at the end of a long day when I didn’t want to climb more. I press my cool gloved hands into my face and take a breath. I wish I had some water, but we finished that an hour ago. I know I can physically go beyond this place. I have to. We have to. No choice but to be careful and do it. I exhale and reach for my ice axes.

Two pitches later, I traverse steep ice in the dark toward a fin of snow. I climb that to a block of solid rock and place a good nut in a finger-width crack. The climbing is steep; I’m on my arms, which are fried from the day’s thousands of swings. I am dizzy, but somehow my body robotically continues. I drag my pick in the crack until it catches and climb to the right. I reach up and swing. It takes four swings to get the pick solidly lodged. Each swing is progressively weaker.

I step one foot out to the right; the pack drags me off balance. My feet hurt. I make another move, somehow, and another, and I’m standing on a solid shelf of ice. I put in a screw before the retching starts.

I drool and hack, my body heaving. Nothing comes up. The stomach pain is otherworldly, transcendent. I think I might faint. “Is this what it takes?” I ask myself. With no answer, I grip the ice screw with one hand and my ice axe with the other, bracing for the next wave.

Vince’s voice calls through the darkness. “You okay?”

I can’t speak. I try to breathe, strings of saliva slap against my chin and my nose is suddenly heavy with snot. I double over, and retch again. Some bile dribbles from my mouth.

Breathe, breathe, breathe. I force my chest open and my posture straight. Pull it together. I finish the pitch by climbing the ice rib. As I place an anchor I can see the maw of a huge crevasse splitting the chin of the hanging glacier: a perfect bivy site, just one pitch of moderate ice away. I look at my watch, midnight. We will be able to pitch our tent on flat snow, sheltered by the overhanging roof of the serac.

Rupal Face Descent – 19,700 Feet on Nanga Parbat, Pakistan: September 7, 2005, 3 pm

The fixed rope, bleached white by untold years hanging in the sun, disappears again into a slope of blue ice. I clip our rope to it, a half-hearted attempt to protect Vince and me from a catastrophic fall, and back down, slowly now. Vince is moving faster on the easier slope above and has no way to know that I’ve slowed. Because of the difference in our pace, the rope pools around my feet. I try to hold it out of the way with one hand and continue backing toward the dark apparition of a rock tower that I hope marks the gully of the lower Messner route.

The tower is round and broken down, but near its flank we find a large frozen coil of fixed rope and a sling of pitons. We’re on route. This old rope is useless, but the pitons are a goldmine. We’ve left most of our rack above. All we have left is a couple of nuts and one ice screw. As long as we have that one screw we can drill V-threads from which to rappel. But it’s a frustrating and tiring chore; each V-thread takes 10 minutes of concentrated effort.

As Vince arrives at the stance I take a medium-size piton from the sling and hammer it into a crack. I clip one of my last carabiners into it and rig the rappel.

“Nice to score some pins,” Vince says as he pulls a headlamp out of his jacket pocket in the descending dusk.

“For sure.” I lean my weight onto the rope. Instead of the hard reassurance of an anchor, I sit back and then slowly keep moving. I jump up. “Whoa!”

“Shit.” Says Vince looking at the half-dislodged piton I had just placed. The rock was just frozen together without being solid. In a rush of adrenaline I spin in the ice screw to make another V-thread.

Two rappels later the adrenaline has faded and I’m laboring to make another V-thread. Vince flips off his light and stands next to me. The fog thins and reveals a thick crop of stars. Below us in the valley, we see five large fires burning.

“Hey. Looks like there’s a party going on down there,” Vince says.

“For us, I’m sure,” I say. The very idea that the two of us are visible to the inhabitants of the Rupal Valley, two tiny black dots on this infinite landscape of ice and stone, is absurd.

I’m suddenly aware that Vince is standing stock still. “I hear drumming,” he says. “Seriously.” He holds up a hand, begging my silence. “I think I hear drumming.”

Several times during my expeditions to Pakistan I’ve witnessed celebrations beat out on improvised instruments such as plastic barrels and kerosene jugs. These local songs are sung to jubilant rhythms and I’ve often been impressed by how happy these people seem to be, living off their bony herds of goats and a small hand-irrigated plot of potatoes. I can’t imagine what the whole valley would be celebrating tonight.

I cock my head down towards the valley. “You’re crazy.” I stand still for one more moment. “I don’t hear anything. I think you’re hallucinating again.” I turn back to building the anchor.

Rupal Face Ascent – 20,000 Feet on Nanga Parbat, Pakistan: September 4, 2005, 8 am

“Rise and shine,” I announce, as the brush of sunlight wakes me. I sit up and lean out of the tent to start the stove. When we crawled inside at 1 am last night we were so worked that all we managed was a bit of soup and one pot of water before we slept.

“Do or die,” Vince says in a faint, ironic voice, flat on his back and groggy from lack of sleep. Indeed, it may now be impossible to descend the 10,000 feet below should we fail to make the summit. From here we must find our way up to the Messner route, and then down climb and rappel from V-threads.

Descending the way we came would require thousands of feet of rappelling where the only anchors would have to be found in the rock for which we lack the gear. Our rack consists of nine pitons, six nuts, five ice screws, and three cams. Without a radio or support team, we have no one to ask for help. If we don’t get rehydrated and refueled we’ll be compromised. We’ve breached 20,000 feet of altitude and we will eat and drink less and less as we get to more extreme altitudes.

As the snow melts in the pot I take out our three photographs of the wall. They offer few hints about the next section. From the valley our binoculars hadn’t revealed any solutions. But my instinct, born of many smaller walls, tells me that we will find our way through.

Far away now, is that boy of 19 who, with a Slovenian expedition, laid at the base of this wall and wondered what he didn’t know about himself. I have been shaped by 16 years and a million decisions made: what I learned, how well I trained, when we went, how long we waited for good weather, for good conditions, where we chose to climb. The sum of my past actions doesn’t determine who I am, but it certainly determines who I may become.

I wonder about Vince. I don’t know what seas he has crossed, what has shaped him. I have noticed that he perceives subtleties in life and art that I miss in my rush to juggle as many projects and activities as I can handle. On the outside Vince looks unapproachable. He often wears anti-religious, pornographic T-shirts. He has multiple body piercings, wears dangling chains and studded black boots. He plays music – Norwegian black metal – which virtually no one else appreciates. This veneer hides a stoic, quiet demeanor and a sensitive, thoughtful, highly articulate person.

At noon we’ve been climbing for two hours and we need food and water. I cut a stance in the ice. There is one big unknown left, one section of headwall still hidden. Vince arrives, but we don’t speak.

I shoulder my pack and start up, uncertainty weighs heavily. “This has to go,” I think as I traverse up and right. Slowly, a hidden corner opens to reveal a broad, chalky flow of ice rolling upward. “Pay dirt!” I holler back to Vince. “It goes! Easy!”

Pushing too hard, 150 feet later I’m exhausted. Foolishly, I’ve just soloed vertical ice with my pack on at 21,000 feet. My irrational exuberance could have killed us both, but I realized it after I was too far up to climb back down. Ashamed at my bad decision and the potential consequences for my partner, I lower the rope to Vince who waits patiently.

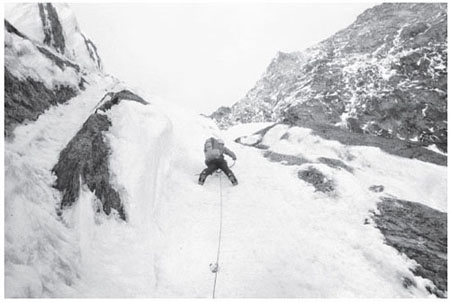

Some of the best ice on the route was on this pitch that I am leading in a gully that will take us through the overwhelmingly steep headwall to my right. We climbed as fast as we could throughout the afternoon; we hadn’t seen a bivouac site all day. VINCE ANDERSON

As evening nudges me onwards I admonish myself: “No mistakes, Farmboy.” Fifty feet above my last ice screw I start chopping at the cornice. “If I can get on top of this ridge maybe we can get a good bivy.”

The cornice breaks suddenly and my body swings out over the dark valley 11,000 feet below. My full weight falls onto one tool as hard blocks of snow crash towards Vince. I hear the dull slaps as they hit him, and then I hear his moans. I step up, slam the shaft of my other tool into the newly exposed slope and pull across. Adrenaline pumping, I scurry down a few feet on the opposite side.

I call down. “Are you okay?”

“Fine,” Vince responds, his voice cracking.

He doesn’t sound fine, but there’s nothing I can do. I continue along the ridge for 20 meters until I find solid rock and build an anchor by headlamp. As I belay Vince, my head pounds from the altitude. He rounds the corner.

“You okay?” I ask again.

“The biggest pieces missed me, but a smaller one hit me on the shoulder pretty good. How’s this look?” he asks dubiously, eyeing the extremely narrow crest.

“Well,” I grab Vince’s pack and reach in to find the small shovel he carries, “let’s find out.”

With a resigned scowl, he takes the shovel from me. “Yeah. Let’s.”

Rupal Face Descent – 15,000 Feet on Nanga Parbat, Pakistan: September 7, 2005, 7:45 pm

We’re down to 15,000 feet. We’ve descended 11,000 feet since leaving the summit three days ago, but we still have nearly 3,000 feet before we get off the face and another 1,000 feet of hiking down to base camp.

At the next anchor, Vince takes off his hat and his headlamp accidentally flies down the slope. We wordlessly watch the light skip down the steep ice gully and disappear. I start the next rappel and my headlamp batteries die when I reach the ends of the ropes. At midnight I rappel by starlight.

Summitting Nanga Parbat had stripped us to our most basic essential selves. Now each step of this descent is a high-pressure debridement of that rawness. Pain immerses me. I don’t crave food or water, just rest: to lie down and let my bones sink into a good flat piece of earth.

Earlier, Vince complained about foot pain, apparently a persistent problem for him. But now he is silent. His artistic aesthetic holds suffering in high regard. That, I think as I rappel away from Vince, his head hung forward, is a man living his ideal.

Near the end of the rope I notice a pointy blackness where no stars shine. It’s a serac, a house-sized piece of ice. Toggling the switch of my headlamp I get a brief burst of faint light before it dies again. Sure enough, there is a flat area at the base of the serac. I climb over, stand comfortably and unclip. I’m too tired to notify Vince of my discovery. As he rappels toward me, I kneel and tease the tent out of its stuff sack. It’s 1 am.

Inside the tent, Vince cooks our last bit of food: a single packet of instant bean soup. With the first bite he gags and spits.

“Ugh, sand!” he moans.

Without a light he hadn’t noticed that the snow here is full of dirt, rocks and sand. He dumps out the soup, and in the darkness, excavates down to what he thinks will be clean snow. We dine on tepid water.

In the morning the fuel canister sputters under a half-melted pot of water. We take turns drinking down the icy broth before piling out of the tent. At such a low altitude and with such fatigue, our sleep has been sound and I am refreshed, but as I stand, the exhaustion and pain returns.

At noon we step off of the Rupal Face.

Rupal Face Ascent – 24,000 Feet on Nanga Parbat, Pakistan: September 5, 2005, 11 am

Day five and we slowly climb the upper gully, which has gradually become less steep. Our goal is to find a good bivy as early as possible so we can rest for the summit attempt tomorrow. At two in the afternoon, at about 24,250 feet, we discover a snow arête and quickly excavate a good tent platform. Our tension, drawn tight for so many days, releases like a relaxed bow. We know that from here we can reach the 1970 Messner route and descend if necessary. I lounge in the tent, enjoying the warm sun.

At half past midnight the alarm chimes. Summit day. Vince, again not having slept, starts the stove and we begin the wait. I stare at the flame, willing it to burn hotter, but the altitude takes its toll on the mechanical as well the human.

At lower altitude mixed climbing is enjoyable, but 100 feet out of the tent I struggle to make even the easiest moves as I fight my cold, oxygen-starved body. When we reach the end of the rock, we tie the climbing rope and most of the gear to a big boulder. We continue with one rucksack containing food, water and clothes, and a five-millimeter static rope for the descent. The one without the pack breaks trail.

The couloir we’re following steepens, and the snow gets deep and loose. Vince wallows in the lead.

“Do you think it could slide?” I ask. An avalanche here would send us for a 12,000-foot fall.

Vince replies that it seems okay, but we both get quiet. Around us, the field of white seems to separate into individual crystals; innumerable factors that configure our success or failure, life or death. At this altitude, it’s hard to know whether our perception, let alone our judgment, is reliable. I take my turn up front, pushing the snow down with my ice tools, crushing it with my knees, then stomping it with a foot so I can raise myself up a few inches. After five minutes, I step aside and Vince has a go. For over two hours we work like that, taking turns up front so we can progress together.

The sixth consecutive clear sunrise colors our rarified world in soft pink. We have gained only 200 feet in two and a half hours: Impossibly slow. We keep working. There’s time left in the day. All our accumulated actions push us forward: all the steps, all the swings, all the luck. And before that, the hours, days and years of preparation.

In the sunlight, I discern a ripple of wind texture on the snow near a rock wall. With one crampon scratching for edges on the rock, and one in the snow, I make faster progress. Soon we’ve gained another 200 feet, and the snow stiffens to where it begins to support our steps. There is unspoken relief, but no certainty.

At 25,000 feet, with the sun high, I’m stripped to a shirt, gloveless, hatless and sweating. I can imagine the summit hiding just behind the crest, but my confidence is so shaken that it seems improbably far. Vince leans his head against his axe, exhausted from four mostly sleepless nights and six marathon days.

The wall drops away below. On its crest we scratch out a place to rest.

“How…ya…doin’,” I spit the question between breaths. It’s so hard to breathe here. Vince looks up, holds his fingers like a pistol and points it at his temple. It hurts to laugh, but I do. If he still has his sense of humor, black as it may be, then he is in good enough shape to continue. Vince shuts his eyes and looks peaceful as he gasps for air. He has pushed beyond all limits, beyond all pain into this, a solitary state of grace.

I strip my sweat-soaked socks, attach them to the rucksack, and reboot with bare feet. When we start again, our pace is slow and our altimeter reads only 25,250 feet, 1,400 feet below the summit. I hope it’s wrong. We wanted to be on the summit by 2 pm, and now I realize how much the deep snow set us back. The sky is clear and windless.

At 2 pm I pause, turn, and announce the time to Vince. The steady look in his eyes tells me what I need to know. There will be no turning back now. I keep breaking trail toward the summit.

At 4 pm we crest a false summit and see the true summit 100 yards away. We rest on a big flat rock, the first place we are able to sit unroped in six days. Vince lies back and soon falls asleep. I put my now-dry socks back on, shake Vince awake, and follow him as he makes the last steps.

Rupal Face Descent – 12,000 Feet on Nanga Parbat, Pakistan: September 8, 2005, 2 pm

Back at tree line Vince and I each follow our own cow trails through the juniper. Suddenly four Pakistani men are running towards us, shouting and waving. I flinch, and try to hide behind a scraggly shrub.

“Great,” I think. “What a perfect time to be captured by a Taliban warlord.” A tall bearded man in Muslim dress throws his arms around me; I brace weakly against the coming blows. But he hugs me, bouncing me up and down as he dances with me held tightly in his arms. I get my elbows up and push him away, trying to focus on his face. With my hands flat against his chest I squint and try to remember another human. It’s our assistant cook Ghulam.

He releases me, smiling, and gleefully shouts something unintelligible and walks a few steps downhill.

“Ghulam?” but he disappears around the other side of a large juniper tree as I follow. I see Vince sitting on his pack drinking from a bottle of water as our liaison officer Aslam stands proudly, preparing to open a box of cookies.

“Steve-sab,” Aslam shouts, and I endure another bear hug, before dropping my pack and taking the water from Vince. It is sweet and viscous and filling.

Rupal Face Ascent – 26,660 Feet at the Summit of Nanga Parbat, Pakistan: September 6, 2005, 5:30 pm

The light is low and the massive shadow of Nanga Parbat reaches across several valleys to the east. My crampons crunch into the summit snow; Vince follows just a few paces behind. Just before the top, I kneel in the snow, overwhelmed by emotion. Years of physical and psychological journey – to make myself strong enough, to discover whether I am brave enough – all fold into this one moment. It seems sacrilegious to step onto the summit.

Watching Vince arrive I know that I could not have completed this climb without him. I stand as he approaches, and I take one step backwards onto the summit of Nanga Parbat. Vince joins me in an embrace. Frozen tears fall to the snow at my feet, becoming part of Nanga Parbat, as it became part of me so many years ago.

An hour before sunset, two exhausted men descend from the summit of Nanga Parbat. It should be deeply frightening to gaze out over the Rupal Face at dusk – and it is. Perhaps nowhere on earth are you so far away from life. In the dark, fear and pain seem more appropriate. Home and love are just flickers of my imagination in the hollow darkness.

In that moment, I understand that on the outer edge of infinity lies nothingness, that in the instant I achieve my objective, and discover my true self, both are lost.