NEWS OF ARGENTIA BROKE up Washington’s summer doldrums, at least for a time. Democratic leaders in Congress hailed the Atlantic Charter as a magnificent statement of war aims—indeed, as a signpost to “real and lasting peace.” Hiram Johnson and Robert Taft accused Roosevelt of making a secret alliance and planning an invasion of Europe. The New York Times, billing the pledge to destroy Nazi tyranny in an eight-column headline, proclaimed that this was the end of isolationism, while the New York Journal-American accused the President of retracing, one by one, all the steps toward war taken by Wilson. Colonel McCormick’s Chicago Tribune, irked by the Roosevelt-Churchill togetherness, reminded its readers that the President was “the true descendant of that James Roosevelt, his great-grandfather, who was a Tory of New York during the Revolution and took the oath of allegiance to the British King.” Both friend and foe saw the meeting as a prelude to more aggressive action.

But not Roosevelt, evidently. Having taken a dramatic step forward, he executed his usual backward hop. Aside from a lackluster message to Congress incorporating the declaration, he took little action to follow it up. At the first press conference after the meeting, on the Potomac, reporters found him cautious. What about actual implementation of the broad declarations, he was asked. “Interchange of views, that’s all. Nothing else.” Were we any closer to entering the war? “I should say, no.” Could he be quoted directly? “No, you can quote indirectly.”

But the meeting at sea did seem popular with the people, according to the pollsters. Seventy-five per cent of those polled had heard about the eight-point credo, and of those about half indicated full or partial approval, while only a quarter of them were cool or hostile. Many were indifferent or uninformed, however, and this number grew as time passed. Five months later most people remembered the two men meeting, but few remembered anything about the Charter itself.

Nor did the conference seem measurably to change popular attitudes toward Roosevelt’s aid-to-Britain program. Those attitudes seemed almost fixed during most of 1941. Asked in May, “So far as you, personally, are concerned, do you think President Roosevelt has gone too far in his policies of helping Britain?” about a quarter answered “too far,” about a quarter “not far enough,” and half “about right.” This pattern persisted with remarkable stability into the fall; evidently the President was shifting step by step with the movement of opinion. On the face of it he was acting as a faithful representative of the people; a majority endorsed his policies and he fell evenly between the critics of both wings. As he took increasingly interventionist action “short of war,” he was holding the great bulk of public support.

The troubling question remained whether, in view of the critical situation abroad, he should be more in advance of opinion than representative of it, more of a catalytic or even a divisive agent than a consensual one, more of a creator and exploiter of public feeling than a reflector and articulator of it.

This was the question Stimson kept raising. When the President phoned him early in the summer to tell him that he had some good news—that a forthcoming Gallup Poll was going to be much more favorable than the Gallup people had expected—Stimson reminded him again that all these polls omitted one factor which the President seemed to neglect—“the power of his own leadership.” Roosevelt had not denied this but had complained that he simply did not feel peppy enough.

It was leadership and decision, after all, that American strategists needed, not merely symbol and pageantry. Early in July the President had asked Stimson to join with Knox and Hopkins in exploring over-all production needs in order to “defeat our potential enemies.” For ten weeks the defense Secretaries had struggled with the question, and then given up. Everything depended on what assumptions they were working under, Stimson wrote to his chief—whether the United States promptly engaged in an avowed all-out military effort against Germany, or merely continued its present policy of helping nations fighting the Axis with munitions, transport, and naval help. The Army, Navy, and Air strategists were united in preferring active participation in the war against Germany, Stimson went on, but work could not be concluded until the President’s views were known.

The military uncertainty was reflected right down the army line. A Nation reporter spent ten days in August tramping up and down Times Square talking with over three hundred Regular soldiers, draftees, National Guardsmen. They were a breezy, cocky lot, confident that any one of them could lick the Germans or an infinite number of Japanese. But, except for the Regulars, they hated the Army, Roosevelt, General Marshall, and Negroes in about equal degree. Few had any idea why they were in the Army or what the Army was for. Some were America Firsters—but they had little suspicion that the Commander in Chief was trying to drag the United States into war. They simply seemed confused. They neither attacked nor defended Roosevelt’s foreign policy; they just did not seem to care.

But there was some logic to their position. They understood the President’s policy of aid to Britain short of war, but if the nation was not preparing to fight Germany, “Why this Army?”

The President had promised Churchill at Argentia that he would use hard language in his message to Tokyo; the Prime Minister had feared that the State Department would try to water it down, and he was right. Hull and his aides felt that the warning might arouse the extremist wing in Japan, and by the time they finished massaging the message it was one more general warning. The President went along with the change. He decided that he could deliver the warning more effectively at a direct confrontation with Nomura. On Sunday afternoon, August 17, 1941, the Japanese Ambassador arrived at the White House.

The old Admiral was hard of hearing, had a glass eye, spoke English uncertainly, and was so fuzzy at times that Hull wondered if he understood his own government’s position, let alone Washington’s. But he was affable and had an encouraging way of nodding responsively, with an occasional mirthless chuckle, to Roosevelt’s and Hull’s main points. The President, in fine fettle after his two weeks at sea, made some pleasant remarks and then spoke gravely, contrasting his country’s peaceful and principled record in the Far East, as he saw it, with Japan’s conquests through force. Did the Admiral have any proposal in mind? Nomura did. Pulling a paper from his pocket, he said that his government was earnestly desirous of peaceful relations—and Premier Konoye proposed a meeting with the President midway in the Pacific.

The President seemed unperturbed at losing the initiative just as he was about to issue his warning. He read the watered-down statement anyway. Even this weak message Roosevelt presented almost defensively. Indeed—or so Nomura reported to Tokyo—the President finally handed him the oral remarks as a matter of information. The lion’s roar of Argentia had become a lamb’s bleat. Even so, Roosevelt reported to Churchill that his statement to Nomura was “no less vigorous” than the one they had planned.

Konoye’s offer to meet Roosevelt was a weak card played from a shaky hand. Dropping Matsuoka had not eased the Premier’s situation at home. Washington’s reaction to the Indochina occupation had been sharper than Tokyo expected; the freeze seemed a direct threat to national survival. The Emperor, Konoye knew, was uneasy about the drift toward conflict with America. The Army under Tojo still took its old expansionist line, but now, to the Premier’s alarm, the oil-conscious Navy was swinging to a more militant stance. The jingo press was attacking Washington for sending oil to Russia via Vladivostok and “Japanese” waters; officials lived under heavy police guard against assassination; extremists in the middle ranks of the Navy and Army were a constant threat. A dramatic meeting with Roosevelt might break the deepening spiral, Konoye calculated, arouse the moderates among the people, enlist the Emperor’s backing, and present the militarists with a fait accompli. He won Tojo’s grudging acquiescence to a parley on condition that if the meeting failed—as the War Minister expected it would—the Premier would return home not to resign but ready to lead the war against the United States.

Playing for the highest stakes, Konoye was so eager for a summit conference that he had Foreign Minister Toyoda sit down with Ambassador Grew and plead, on a long, stifling evening, for Grew’s support for the idea. He prepared a special ship for the voyage to the conference and planned to take a brace of admirals and generals, all of them moderates, to “share responsibility” with him. In order to bypass Hull, Nomura would deliver Konoye’s invitation to the President personally; a conciliatory note was prepared for Hull in a style calculated not to excite him.

The notes that Nomura handed Roosevelt on the morning of August 28 were full of benevolence and vague promises. Konoye renewed his invitation to meet—and to do so soon in the light of the present situation, which was “developing swiftly and may produce unforeseen contingencies.” Roosevelt remarked that he liked the tone and spirit of Konoye’s message. The note from the Japanese government indicated its willingness to withdraw from Indochina as soon as the China incident was settled, not to attack Russia, and indeed not to attack anyone, north or south. Roosevelt interrupted the reading of the note to offer some small rebuttals, and he could not resist the temptation, with what seemed to Nomura a cynical smile, to ask whether there would be an invasion of Thailand while he might be meeting with Konoye, just as Indochina had been invaded during Hull’s conversations with Nomura.

Still, Roosevelt was sorely tempted to parley. A rendezvous in the Pacific would be a dramatic counterpart to his trip to Argentia; the Japanese seemed to be in a conciliatory mood; and he always had confidence in his ability to persuade people face to face. He even proposed Juneau as a place to confer, on the ground that it would require him to be away two weeks rather than three. But now the President ran into serious difficulties among his advisers.

Hull and the old Far Eastern hands in his Department opposed a conference unless the major questions were settled—and settled to Washington’s liking—in advance. The Secretary seemed to take a mixed approach to Japan: he never tired of stating his principles and flailing Japan for not living up to them; he opposed conciliation because he had no faith in Konoye’s ability to check the military; but he also opposed drastic action. He had both a devil theory of Japanese politics and an aversion to a showdown—an ambivalence that precluded any consistent policy except endless pieties, conversations, and delays. And Hull could hardly have welcomed another ocean conference where the President, off in the heady sea breezes with advisers like Welles and Hopkins, might take steps—like the warning to Japan drawn up at Argentia—that could upset Hull’s patient diplomacy.

In Tokyo, Grew took the opposite stand. Though long a hardliner toward Japan, he had seized on a Pacific rendezvous as the last-best hope of averting a showdown. He urged Hull not to reject the Japanese proposal “without very prayerful consideration.” Konoye would not request such a meeting, he argued, unless he was willing to make concessions; he was determined to overcome the extremists, even at peril to his own life. At the most, Grew contended, Japan would make concessions on Indochina and China; at the very least a meeting would slow the growing momentum toward a head-on collision. He ended with a grim warning: if the meeting did not take place, new men would come to power and launch a do-or-die effort to take over all of Greater East Asia—which would mean war with the United States.

When faced with conflicting advice Roosevelt rarely made immediate clear-cut choices; in this case he took the expedient course of continuing to talk hopefully of a meeting while following Hull’s advice to demand agreement on fundamental principles before consenting to a rendezvous. Calling Nomura to the White House on September 3, the President carefully dealt with the Japanese proposal of the week before. He appreciated Konoye’s difficulties at home, he told the Ambassador, but he had difficulties, too. While Hull sat by, Roosevelt read the Secretary’s four fundamental principles: respect for other nations’ territorial integrity and sovereignty; noninterference in other nations’ internal affairs; equality of commercial opportunity; nondisturbance of the status quo in the Pacific except through peaceful means. He was pleased, said the President, that Japan had endorsed these principles explicitly in its note of August 28. But, since there was opposition to such principles in certain quarters in Japan, what concrete concessions would Tokyo make in advance of the summit conference?

While Roosevelt played for time, other less visible decision makers in Japan were facing their own urgencies during August. Washington’s freezing order of late July along with increasing indications that Russia would hold on were forcing Army and Navy planners in Tokyo to abandon thoughts of attacking the Soviets from the rear, at least during 1941, and to look south. The only way to overcome American, British, and Dutch power, it was decided, was through a series of lightning attacks. Such a plan would be heavily dependent on weather—on tides, phases of the moon, monsoons—and on moving fast, before oil gave out. On September 3 the military chiefs and the Cabinet met in a liaison conference. “We are getting weaker,” Navy Chief of Staff Osami Nagano stated bluntly at the outset. “The enemy is getting stronger.” A timetable must be set. Military preparations must get under way even while diplomacy continued. While Cabinet members sat by, Navy and Army chiefs soberly discussed plans. Finally it was agreed: “If, by the early part of October, there is still no prospect of being able to attain our demands, we shall immediately decide to open hostilities against the United States, Great Britain, and the Netherlands.”

So a timetable had been set. In all the tortuous windings toward war, this was the single most crucial step. Why did Konoye agree? Partly because he had high hopes for his conference with Roosevelt—he would let the military play their game if they would let him play his. And partly because of the Emperor, who presumably could keep the military in line. On September 5 Konoye’s Cabinet unanimously approved the action of the liaison conference. The Premier then hurried to the palace to inform the Emperor.

Hirohito was in an almost imperious mood. He listened to Konoye with apparently rising concern, then questioned him sharply. Were war preparations gaining precedence over diplomacy? Konoye said no, but suggested that the Emperor ask the military chiefs. Nagano and the Chief of the Army General Staff, Hajime Sugiyama, were summoned to the throne room. The Emperor questioned Sugiyama on military aspects of the plan. How long would a war with the United States last? For the initial phase about three months, the General said. The Emperor broke in: Sugiyama as War Minister in 1937 had said that the China incident would be over in a month; it was still going on. This was different, Sugiyama said; China was a vast hinterland, while the southern area was composed of islands. This only aroused the Emperor further. “If you call the Chinese hinterland vast would you not describe the Pacific as even more immense?” Sugiyama looked down at his boots and was silent.

Next morning Hirohito called in his Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal, Koichi Kido. In a few minutes an imperial conference was to start; the Emperor had decided that he would speak out, he told Kido, and inform the military that he would not sanction war as long as the possibility of a settlement remained. Kido said smoothly that he had already asked Yoshimichi Hara, the President of the Privy Council, to ask the questions for the Emperor; it would be more appropriate for His Majesty to make any comments at the end.

Soon the Cabinet and the Chiefs of Staff were seated across from the Emperor on hard chairs in the east wing of the palace. One after another his ministers went through their carefully prepared recitations. The Empire would go to war by the end of October, declared Konoye, unless diplomacy had achieved its “minimum demands.” These were: America and Britain should not hinder settlement of the China incident; they would cease helping the Chungking regime; they would not strengthen their military position in the Far East; they would co-operate with Japan economically. Japan’s “maximum concessions” were: not to advance militarily from Indochina; to withdraw its forces from Indochina after peace was established; to guarantee the neutrality of the Philippines.

Nagano spoke next. Vital supplies—especially oil—were dwindling. Time was vital. He sketched the necessary strategy if war broke out. If the enemy aimed for a quick war and early decisions and dispatched their fleet, “this would be the very thing we hope for.” With aircraft “and other elements” he could beat them in the Pacific. More likely, though, “America will attempt to prolong the war, utilizing her impregnable position, her superior industrial power, and her abundant resources.” In a long war Japan’s only chance, after the first quick strikes, was to seize the enemy’s major military areas, establish an impregnable position, and develop military resources. Sugiyama then spoke up. He expressed the Army’s complete agreement with Nagano. Japan must not mark time and be trapped by Anglo-American intrigue and delays. Intensive troop movements were required. If negotiations failed, a decision for war must be made within ten days of the failure at the latest. Others spoke, but there was no break in the united front.

The Emperor became flushed as Hara went through set questions and received set replies. A hush fell on the room. His Majesty was not satisfied with the assurances about diplomacy first. He drew a slip from his pocket and in his high voice read a poem composed by his grandfather the Emperor Meiji:

“All the seas, in every quarter, are as

brothers to one another,

Why, then, do the winds and waves of strife

rage so turbulently throughout the world?”

The Emperor’s meaning was clear. All present were struck with awe, Konoye remembered, and there was silence throughout the hall. Nagano assured the Emperor that the whole Cabinet favored diplomacy first. The meeting adjourned in an atmosphere of unprecedented tension.

At just about this moment, on the other side of the world, the American destroyer Greer was speeding through North Atlantic waters on a mail run to Iceland. These waters were in both the German war zone and the American defense zone. A British patrol plane signaled her that a submerged U-boat lay athwart her course ten miles ahead. The Greer speeded up, sounded general quarters, zigagged toward the submarine, made sound contact, and began trailing the U-boat and reporting its exact position to the plane, but with no intention of attacking it. After an hour the plane dropped four depth charges without effect and turned back to refuel; the Greer hung on her quarry’s trail. After two hours of this the submarine suddenly launched a torpedo at the Greer, and then one or two more. The Greer dodged them and began dropping a circle of depth charges, meantime losing contact. Over two hours later the Greer made contact again and dropped eleven more depth charges. The Greer trailed the U-boat a while longer, then broke off the pursuit, leaving it in the hands of British destroyers and planes in the area.

At last Roosevelt had his incident. It was not much of an incident, since the Greer had sought out the submarine and had jeopardized it by broadcasting its position; moreover, there was no indication (as the White House was informed) that the Germans even knew whether the destroyer was British or American. But shots had been exchanged in anger, and Roosevelt felt that here was his chance to dramatize the Nazi menace that he had long been picturing. He found Hull in an equally stern and even aggressive mood; the Secretary waxed so indignant about the situation that the President asked him to put it all in writing for a White House address. It was announced that the President would make a major statement the following Monday. Churchill wired that all were awaiting his speech with profound interest. The President went to Hyde Park for the weekend.

While he was there, on Saturday, September 6, his mother died, suddenly and peacefully, in her pleasant corner room looking out toward the Albany Post Road. What private grief Roosevelt felt at this loss, breaking his main link with his childhood, no one could tell, for he said little. But perhaps Mackenzie Ring was uttering Roosevelt’s own thoughts when the Prime Minister wrote him later that one could not see “the main theatre of all one’s actions since childhood’s days” suddenly removed, “as Mrs. Roosevelt’s passing must have been to you, without experiencing a sorrow much too great to express in words.”

The President instructed Rosenman and Hopkins to continue work on his speech, which was now postponed to the eleventh. Back in Washington he read a draft of it to his Cabinet; all approved but Hull, who was now arguing for a strongly moralistic speech, though without threat of action. Roosevelt refused to tone it down.

“The Navy Department of the United States,” he began his fireside chat, “has reported to me that on the morning of September fourth the United States destroyer Greer, proceeding in full daylight toward Iceland, had reached a point southeast of Greenland. She was carrying American mail to Iceland. She was flying the American flag. Her identity as an American ship was unmistakable.

“She was then and there attacked by a submarine. Germany admits that it was a German submarine. The submarine deliberately fired a torpedo at the Greer, followed later by another torpedo attack. In spite of what Hitler’s propaganda bureau has invented, and in spite of what any American obstructionist organization may prefer to believe, I tell you the blunt fact that the German submarine fired first upon this American destroyer without warning, and with deliberate design to sink her.

“Our destroyer, at the time, was in waters which the Government of the United States had declared to be waters of self-defense—surrounding outposts of American protection in the Atlantic.”

The President described these outposts and their role in protecting the lifelines to Britain. To people in the room with him, the mourning band for his mother showed somberly against his light-gray seersucker suit.

“This was piracy—piracy legally and morally.” The President then reviewed a series of earlier incidents in the Atlantic, beginning with the Robin Moor. “In the face of all this, we Americans are keeping our feet on the ground.…It would be unworthy of a great Nation to exaggerate an isolated incident, or to become inflamed by some one act of violence. But it would be inexcusable folly to minimize such incidents in the face of evidence which makes it clear that the incident is not isolated, but is part of a general plan….Hitler’s advance guards—not only his avowed agents but also his dupes among us—have sought to make ready for him footholds and bridgeheads in the New World, to be used as soon as he has gained control of the oceans.” Hitler was seeking world mastery, and Americans of all the Americas must give up the romantic delusion that they could go on living peacefully in a Nazi-dominated world.

“We have sought no shooting war with Hitler. We do not seek it now. But…when you see a rattlesnake poised to strike, you do not wait until he has struck before you crush him….

“Do not let us be hair-splitters. Let us not ask ourselves whether the Americas should begin to defend themselves after the first attack, or the fifth attack, or the tenth attack, or the twentieth attack.

“The time for active defense is now.” The President called the roll of early Presidents who had defended the freedom of the seas.

“My obligation as President is historic; it is clear. It is inescapable.

“It is no act of war on our part when we decide to protect the seas that are vital to American defense. The aggression is not ours. Ours is solely defense.

“But let this warning be clear. From now on, if German or Italian vessels of war enter the waters, the protection of which is necessary for American defense, they do so at their own peril….

“The sole responsibility rests upon Germany. There will be no shooting unless Germany continues to seek it….

“I have no illusions about the gravity of this step. I have not taken it hurriedly or lightly. It is the result of months and months of constant thought and anxiety and prayer….”

Shoot on sight. Roosevelt was in effect declaring naval war on Germany, in response to the war of aggression he believed Germany was waging against his nation. The Atlantic cold war was over; now it was a hot war, limited only by America’s neutrality laws and by Hitler’s restraints on his submarine fleet. It was war nonetheless, and Roosevelt proceeded to act in those terms. Two days after his speech he ordered Admiral King officially to protect not only American convoys to Iceland but also shipping of any nationality that might join such convoys. A delighted Churchill at once diverted about forty destroyers and corvettes from the convoy area to duty elsewhere. If any doubt remained, Secretary Knox cleared it up at the American Legion convention in Milwaukee on September 15: “Beginning tomorrow…the Navy is ordered to capture or destroy by every means at its disposal Axis-controlled submarines or surface raiders in these waters.

“That is our answer to Mr. Hitler.”

Mr. Hitler was infuriated by Roosevelt’s escalation, but he was still playing it cool. Raeder made the long trip to the Führer’s Wolfsschanze headquarters on the Eastern Front to protest that the United States had declared war, that his U-boats either must be allowed to attack American warships or must be withdrawn, but Hitler insisted on no incidents—at least before about the middle of October. By that time the “great decision in the Russian campaign” would have been reached; and then, Hitler implied, he and Raeder could deal with the Americans. Glumly Raeder withdrew his proposal.

Roosevelt’s fireside chat seemed to win wide support at home. In mid-September people favored “shoot on sight” by roughly two to one. The President had acted, indeed, on a foundation of public support; by even stronger ratios, polled Americans had favored American convoys for war goods at least as far as Iceland. But these polls could not measure intensity of feeling, and observers sensed a good deal of apathy among the public, or at least a feeling of fatalism. Opinion seemed to be volatile and moody, except when a question touched on the possibility of outright war. Then the people shrank from action. Clearly many Americans were still accepting at face value Roosevelt’s promise that his defense measures would help America keep out of war.

The President judged opinion ripe for the next step—modification of the Neutrality Act, which was still barring the arming of American merchantmen and excluding them entirely from proclaimed combat zones. Interventionist newspapers were now in full cry against the act: it was worth a thousand submarines to the foe, declared the New York Times; it was a “hoary and decrepit antique,” according to the New York Post; it had become a “stench in the nostrils” of the editors of the New York Herald Tribune. But the isolationists in Congress were not prepared to discard a measure that had been both an emblem of American virginity among world predators and a chastity belt to foil them. Senator Taft and others contended that repeal of the Neutrality Act would be equivalent to a declaration of war.

Remembering his one-vote margin on the draft-extension bill of August, the President decided against challenging the whole isolationist bloc. He would call for modification of neutrality rather than total repeal—above all, for authorization to arm American merchant ships. Soon his speech writers were at work on his proposals to Congress. The message was a direct and hard-hitting plea that Congress stop playing into Hitler’s hands and that it untie Roosevelt’s. But the President was adamant on the main tactic. Modification of neutrality must be presented to Congress not as any kind of challenge to the enemy but as a simple matter of the defense of American rights.

One could sense at the end of summer 1941 that the war was rushing toward another series of stupendous climacterics. German troops had isolated Leningrad and broken through Smolensk on the road to Moscow, had surrounded and overwhelmed four Russian armies in the Kiev sector; through the two-hundred-mile gap they had torn in the south the Nazis could see the grain of the eastern Ukraine and the oil of the Caucasus. Churchill was preparing a strong blow in North Africa and pressing for a bolder policy in Southeast Asia. Tokyo was vacillating between peace and war, under a dire timetable. Chungking’s morale seemed to be ebbing away. Washington and London were stepping up the Battle of the Atlantic. And in Moscow, around the end of September, the first flakes of snow fell silently on the Kremlin walls.

Pressure from all these sectors converged on the man in the White House. Allies were stepping up their demands; enemies, their thrusts. His Cabinet war hawks battered him with conflicting advice. But Roosevelt under stress seemed only to grow calmer, steadier, more deliberate and even cautious. He joshed and jousted with the reporters even while artfully withholding news. He listened patiently while Ickes for the tenth time—or was it the hundredth?—maneuvered for the transfer of Forestry from Agriculture to Interior—an effort that the President might have found exquisitely irrelevant to the war except that he himself seemed excited by a plan to establish roe deer in Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

But Roosevelt was not impervious to the strain. More than ever before he seemed to retreat into his private world. He spent many weekends at Hyde Park, partly in settling his mother’s estate. He devoted hours to planning a Key West fishing retreat for Hopkins and himself; he even roughed out a sketch for a hurricane-proof house. He found time to talk to the Roosevelt Home Club in Hyde Park, to Dutchess County schoolteachers, to a local grange. And always there were the long anecdotes about Washington during World War I days, about Campobello and Hyde Park.

Physically, too, the President was beginning to show the strain. Systolic hypertension had been noted four years earlier and not considered cause for concern; but—far more serious—diastolic hypertension was diagnosed during 1941. Dr. McIntire was no longer so rosily optimistic, though he said nothing publicly to temper his earlier statements. His patient was eating, exercising, and relaxing less, showing more strain, and carrying more worries to bed, than he had during the earlier years in the White House. But the President rarely complained and never seemed very curious about his health. Doubtless he felt that he had enough to worry about abroad.

Tension was rising, especially in the Far East. The imperial rebuke spurred Konoye to redoubled efforts at diplomacy even as the imperative timetable compelled generals and admirals to step up their war planning. The government seemed schizophrenic. All great powers employ military and diplomatic tactics at the same time; but in Japan the two thrusts were competitive and disjointed, with the diplomats trapped by a military schedule.

Subtly, almost imperceptibly, Konoye and the diplomats beat a retreat in the face of Washington’s firm stand. Signals were confused: Nomura acted sometimes on his own; messages were also coming in via Grew and a number of unofficial channels; and Konoye and Toyoda had to veil possible concessions for fear extremists would hear of them and inflame the jingoes. The Japanese military continued to follow its own policies; amid the delicate negotiations, Washington learned that the Japanese Army was putting more troops into Indochina. The political chiefs in Tokyo, however, seemed willing to negotiate. On the three major issues Tokyo would: agree to follow an “independent” course under the Tripartite Pact—a crucial concession at this point, because America’s widening confrontation with Germany raised the fateful possibility that Tokyo would automatically side with Berlin if a hot war broke out; follow co-operative, nondiscriminatory economic policies, a concession that was as salve to Hull’s breast; and be willing to let Washington mediate a settlement between Japan and China.

Day after day Hull listened to these proposals courteously, discussed them gravely—and refused to budge. He insisted that Tokyo be even more specific and make concessions in advance of a summit conference. By now the Secretary and his staff conceded that Konoye was “sincere.” They simply doubted the Premier’s capacity to bring the military into line. That doubt did not end after the war when historians looked at the evidence, which reflected such a shaky balance of power in Tokyo that Konoye’s parley might have precipitated a crisis rather than have averted it. Konoye had neither the nerve nor the muscle for a supreme stroke. Much would have depended on the Emperor, and the administration did not fully appreciate in September either his desire for effective negotiations or his ability to make his soldiers accept their outcome.

The mystery lay not with Hull, who was sticking to his principles, but with Roosevelt, who was bent on Realpolitik as well as morality. The President still had one simple approach to Japan—to play for time—while he conducted the cold war with Germany. Why, then, did he not insist on a Pacific conference as an easy way to gain time? Partly because such a conference might bring a showdown too quickly; better, Roosevelt calculated, to let Hull do the thing he was so good at—talk and talk, without letting negotiations either lapse or come to a head. And partly because Roosevelt was succumbing to his own tendency to string things out. He had infinite time in the Far East; he did not realize that in Tokyo a different clock was ticking.

Amid the confusion and miscalculation there was one hard, unshakable issue: China. In all their sweeping proposals to pull out of China, the Japanese insisted, except toward the end, on leaving some troops as security, ostensibly at least, against the Chinese Communists. Even the Japanese diplomats’ definite promises on China seemed idle; it was as clear in Washington as in Tokyo that a withdrawal from a war to which Japan had given so much blood and treasure would cause a convulsion.

Washington was in almost as tight a bind on China as was Tokyo. During this period the administration was fearful of a Chinese collapse. Chungking was complaining about the paucity of American aid; some Kuomintang officials charged that Washington was interested only in Europe and hoped to leave China to deal with Japan. Madame Chiang at a dinner party accused Roosevelt and Churchill of ignoring China at their Atlantic meeting and trying to appease Japan; the Generalissimo chided his wife for her impulsive outburst but did not disagree. Every fragment of a report of a Japanese-American détente set off a paroxysm of fear in Chungking. Through all their myriad channels into the administration the Nationalists were maintaining steady pressure against compromise with Tokyo and for an immensely enlarged and hastened aid program to China.

Even the President’s son James, as a Marine captain, urged his father to send bombers to China, in response to a letter from Soong stating that in fourteen months “not a single plane sufficiently supplied with armament and ammunition so that it could actually be used to fire has reached China.” Chiang was literally receiving the run-around in Washington as requests bounced from department to department and from Americans to British and back again. Its very failure to aid China made the administration all the more sensitive to any act that might break Kuomintang morale.

So Roosevelt backed Hull’s militant posture toward Tokyo. When the Secretary penciled a few lines at the end of September to the effect that the Japanese had hardened their position on the basic questions, Roosevelt said he wholly agreed with his conclusion—even though he must have known that Hull was oversimplifying the situation to the point of distortion. Increasingly anxious, Grew, in Tokyo, felt that he simply was not getting through to the President on the possibilities of a summit conference. On October 2 Hull again stated his principles and demanded specifics. The Konoye government in turn asked Washington just what it wanted Japan to do. Would not the Americans lay their cards on the table? Time was fleeting; the military now were pressing heavily on the diplomats. At this desperate moment the Japanese government offered flatly to “evacuate all its troops from China.” But the military deadline had arrived. Was it too late?

Not often have two powers been in such close communication but with such faulty perceptions of each other. They were exchanging information and views through a dozen channels; they were both conducting effective espionage; there were countless long conversations, Hull having spent at least one hundred hours talking with Nomura. The problem was too much information, not too little—and too much that was irrelevant, confusing, and badly analyzed. The two nations grappled like clumsy giants, each with a dozen myopic eyes that saw too little and too much.

For some time Grew and others had been warning Washington that the Konoye Cabinet would fall unless diplomacy began to score; the administration seemed unmoved. On October 16 Konoye submitted his resignation to the Emperor. In his stead Hirohito appointed Minister of War Hideki Tojo. The news produced dismay in Washington, where Roosevelt canceled a regular Cabinet meeting to talk with his War Cabinet, and a near-panic in Chungking, which feared that the man of Manchuria would seek first of all to finish off the China incident. But reassurances came from Tokyo: Konoye indicated that the new Cabinet would continue to emphasize diplomacy, and the new Foreign Minister, Shigenori Togo, was a professional diplomat and not a fire-breathing militarist. As for Tojo, power ennobles as well as corrupts. Perhaps it had been a shrewd move of the Emperor, some of the more helpful Washingtonians reflected, to make Tojo responsible for holding his fellow militarists in check.

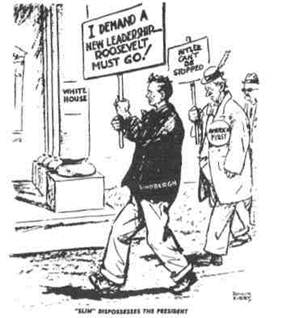

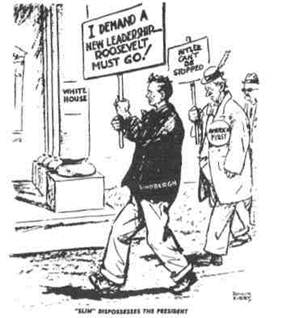

October 13, 1941, Rollin Kirby, reprinted by permission of the New York Post

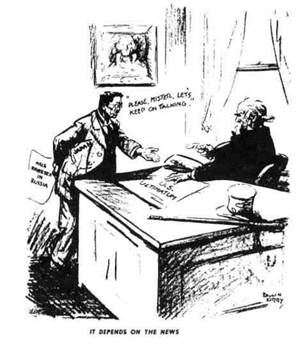

October 31,1941, Rollin Kirby, reprinted by permission of the New York Post

So for a couple of weeks the President marked time. Since he was still following the diplomacy of delay, he could only wait for the new regime in Tokyo to take the initiative—and to wonder when the next clash would occur in the Atlantic.

That clash came on the night of October 16. About four hundred miles south of Iceland a slow convoy of forty ships, escorted by only four corvettes, ran into a pack of U-boats. After three ships were torpedoed and sunk, the convoy appealed to Reykjavik for help, and soon five American destroyers were racing to the scene. That evening the submarines, standing out two or three miles from the convoy and thus beyond the range of the destroyers’ sound gear, picked off seven more ships. The destroyers, which had no radar, thrashed about in confusion in the pitch dark, dropping depth bombs; when the U.S.S. Kearny had to stop to allow a corvette to cross her bow, a torpedo struck her, knocked out her power for a time, and killed eleven of her crew. She struggled back to Iceland nursing some bitter lessons in night fighting.

At last the first blood had been drawn—and it was American blood (though the U-boat commander had not known the nationality of the destroyer he was firing at). News of the encounter reached Washington on the eve of a vote in the House on repealing the Neutrality Act’s ban against the arming of merchant ships. Repeal passed by a handsome majority, 259 to 138. The bill had now to go to the Senate. On Navy Day, October 27, the President took up the incident. He reminded his listeners, packed into the grand ballroom of Washington’s Mayflower Hotel, of the Greer and Kearny episodes.

“We have wished to avoid shooting. But the shooting has started. And history has recorded who fired the first shot. In the long run, however, all that will matter is who fired the last shot.

“America has been attacked. The U.S.S. Kearny is not just a Navy ship. She belongs to every man, woman, and child in this Nation….”

The President said he had two documents in his possession: a Nazi map of South America and part of Central America realigning it into five vassal states; and a Nazi plan “to abolish all existing religions—Catholic, Protestant, Mohammedan, Hindu, Buddhist, and Jewish alike”—if Hitler won. “The God of Blood and Iron will take the place of the God of Love and Mercy.” He denounced apologists for Hitler. “The Nazis have made up their own list of modern American heroes. It is, fortunately, a short list. I am glad that it does not contain my name.” The President had never been more histrionic. He reverted to the clashes on the sea. “I say that we do not propose to take this lying down.” He described steps in Congress to eliminate “hamstringing” provisions of the Neutrality Act. “That is the course of honesty and of realism.

“Our American merchant ships must be armed to defend themselves against the rattlesnakes of the sea.

“Our American merchant ships must be free to carry our American goods into the harbors of our friends.

“Our American merchant ships must be protected by our American Navy.

“In the light of a good many years of personal experience, I think that it can be said that it can never be doubted that the goods will be delivered by this Nation, whose Navy believes in the tradition of ‘Damn the torpedoes; full speed ahead!’ ”

Some had said that Americans had grown fat and flabby and lazy. They had not; again and again they had overcome hard challenges.

“Today in the face of this newest and greatest challenge of them all, we Americans have cleared our decks and taken our battle stations….”

It was one of Roosevelt’s most importunate speeches, but it seemed to have little effect. After a week of furious attacks by Senate isolationists, neutrality revision cleared the upper chamber by only 50 to 37. In mid-November a turbulent House passed the Senate bill by a majority vote of only 212 to 194. The President won less support from Democrats on this vote than he had on Lend-Lease. It was clear to all—and this was the key factor in Roosevelt’s calculations—that if the administration could have such a close shave as this on the primitive question of arming cargo ships, the President could not depend on Congress at this point to vote through a declaration of war. Three days after Roosevelt’s Navy Day speech the American destroyer Reuben James was torpedoed, with the loss of 115 of the crew, including all the officers; Congress and the people seemed to greet this heavy loss with fatalistic resignation.

It was inexplicable. In this looming crisis the United States seemed deadlocked—its President handcuffed, its Congress irresolute, its people divided and confused. There were reasons running back deep into American history, reasons embedded in the country’s Constitution, habits, institutions, moods, and attitudes. But the immediate, proximate reason lay with the President of the United States. He had been following a middle course between the all-out interventionists and those who wanted more time; he had been stranded midway between his promise to keep America out of war and his excoriation of Nazism as a total threat to his nation. He had called Hitlerism inhuman, ruthless, cruel, barbarous, piratical, godless, pagan, brutal, tyrannical, and absolutely bent on world domination. He had even issued the ultimate warning: that if Hitler won in Europe, Americans would be forced into a war on their own soil “as costly and as devastating as that which now rages on the Russian front.”

Now—by early November 1941—there seemed to be nothing more he could say. There seemed to be little more he could do. He had called his people to their battle stations—but there was no battle. “He had no more tricks left,” Sherwood said later. “The bag from which he had pulled so many rabbits was empty.” Always a master of mass influence and personal persuasion, Roosevelt had encountered a supreme crisis in which neither could do much good. A brilliant timer, improviser, and manipulator, he confronted a turgid balance of powers and strategies beyond his capacity to either steady or overturn. Since the heady days of August he had lost the initiative; now he could only wait on events. And events with the massive impact that would be decisive were still in the hands of Adolf Hitler.

The crisis of presidential leadership mirrored the dilemma of national strategy in the fall of 1941. According to long-laid plans, the United States, in the event of war, would engage directly with Germany and stall off or conduct a holding action with Japan. Roosevelt was expecting a confrontation with Germany, probably triggered by some incident in the Atlantic, but he was evading a showdown with Japan. In his denunciations of Nazism he had been careful not to mention Nipponese aggression or imperialism. But Hitler still pointedly avoided final trouble in the Atlantic, while the Far Eastern front, instead of being tranquilized, was becoming the most critical one.

And if war did break out in the Pacific—what then? The chances seemed strong that the Japanese would strike directly at British or Dutch posssessions, not American. Sherwood posed the question well. If French isolationists had raised the jeering cry “Why die for Danzig?” why should Americans die to protect the Kra Isthmus, or British imperialism in Singapore or Hong Kong, or Dutch imperialism in the East Indies, or Bolshevism in Vladivostok? It would no longer be enough for the United States to offer mere aid. Doubtless Roosevelt could ram through a declaration of war—but how effective would a bitter and divided nation be in the crucible of total war? And if the United States did not forcibly resist Japanese aggression against Britain and Holland, what would happen to Britain’s defenses in the Far East while so heavily committed at home, in the Middle East, in North Africa, and on the seven seas?

The obvious answer was to stall Tokyo as long as possible. Eventually an open conflict with Germany must come; if Japan had not yet entered the war, perhaps it would stay out for the same reason it had kept clear of the Russo-German conflict. By November 1941 Roosevelt needed such a delay not only because of Atlantic First, but also as a result of a shift in plans for the Philippines. Earlier, the archipelago had been assumed to be indefensible against a strong enemy assault, and hence the War and Navy Departments had not made a heavy commitment there. Now, with General MacArthur’s appointment as commander of U.S. forces in the Far East and the development of the B-17 heavy bomber, the Philippines were once again considered strategically viable. But time was needed, at least two or three months.

So early hostilities with Japan would mean the wrong war in the wrong ocean at the wrong time. Yet it was clear by November 1941 that the United States was faced with the growing probability of precisely this war. Why did not the President string the Japanese along further, taking care not to get close to a showdown?

This is what he did try, at least until November. It was not easy. Every time reports spread that Washington had considered even a small compromise on the central issue of a Japanese withdrawal from China, frantic cries arose from Chungking. Churchill, too, pressed insistently for a harder line toward Tokyo. At home Roosevelt had to deal with public attitudes that turned more militantly against Japan than against Germany. In early August those opposing war with Japan outnumbered those favoring it by more than three to one, while by late November twice as many as not were expecting war between their country and Japan in the near future.

Doubtless the basic factor, though, was one of calculation, or analysis. Churchill, still responding to the bitter lessons of Munich, contended that a policy of firmness was precisely the way to earn peace; it was the democracies’ vacillation that tempted aggressors to go to war. Roosevelt was not so sure that the Asiatic mind worked in just this way. Yet he went along with Churchill’s theory of peace through firmness and with Hull’s insistence on adherence to principles, rather than with Stimson’s and Knox’s urgent advice to stall the Japanese along in order not to be diverted from Atlantic First and in order to have time to prepare in the Pacific.

Later an odd notion would arise that the President, denied his direct war with Hitler, finally gained it through the “back door” of conflict with the Japanese. This is the opposite of what he was trying to do. He wanted to avoid war with Japan because—like all the grand strategists—he feared a two-front war, and American strategy was definitely set on fighting Hitler first. In another three or six months, after the Philippines and other Pacific outposts had been strengthened, the President might well have gone through the “back door” of war—but not in late 1941. Churchill’s calculations, however, were more mixed. He could assume his stand-firm posture with far more equanimity than Roosevelt; the Prime Minister could reason that a Japanese-American break would probably bring the United States into the German war as well and thus realize London’s burning hope of full American involvement. But much would depend on the strength of Berlin-Tokyo solidarity and on each nation’s calculus of its interest. Churchill had to face the fearsome possibility that the United States might become involved only in the Pacific. Hence he, too, was following the Atlantic First strategy.

It was not Roosevelt’s calculation that was at fault, but his miscalculation. And because he lacked the initiative, and was assuming the imperfect moral stand of condemning Hitlerism as utterly evil and bent on world domination without openly and totally combating it, he faced a thicket of secondary but irksome troubles. Labor was restive in the fall of 1941 as it saw its chance to get in on the war boom. For many businessmen it was still business as usual. The Supply Priorities and Allocations Board had been set up on top of OPM in August, but SPAB seemed to be working with little more effectiveness than its predecessors. Congress seemed incapable of passing an effective price-control bill. Military aid to Allies, though rising, was still inadequate in the face of gigantic demands, and the orderly flow of food and munitions was disrupted by sudden emergencies and shifting needs.

Stimson was still insisting that ills such as these could be remedied only if the President assumed clear moral leadership, took the initiative against Germany, and established definite priorities at home and abroad. But Roosevelt would not yet ask for a declaration of war. Rather, he would try by management and maneuver to swing his nation’s weight into the world balance.

To relations with Moscow in particular Roosevelt applied his most delicate hand. Russia’s sagging defenses in the Ukraine had produced no reversal of opinion among Congress and people, or of policy in the White House. The hard-core isolationists still opposed aid to the Soviet Union and expressed gratification that Russians and Germans were bleeding one another to death; that conflict, said the Chicago Tribune, was the only war for a century that civilized men could regard with complete approval. Roosevelt, who was holding all negotiations with the Kremlin tightly in his own hands, was granting dollars and other aid in small dabs while recognizing that Russia needed massive help. He took care not to propose—or even discuss—bringing the Soviets under Lend-Lease until after Congress passed a big fall appropriation for the program.

The President was showing his usual respect for public opinion, which as always was shrill, divided, inchoate, and waiting for leads. He was especially wary of Catholic feeling against involvement with Bolshevism. With his implicit encouragement, at least, his friend Supreme Court Justice Frank Murphy told fellow Catholics that Communism and Nazism were equally godless but the latter was godlessness plus ruthlessness. When the President, however, suggested to reporters that Russians had some freedom of religion under their constitution, religious leaders pounced on him for his “sophistry” and ignorance. Ham Fish proposed that the President invite Stalin to Washington and have him baptized in the White House pool. Roosevelt dispatched his envoy Myron Taylor back to Rome to sound out Pope Pius and to inform him that “our best information is that the Russian churches are today open for worship and are being attended by a very large percentage of the population.” Taylor carried with him a letter from President to Pope granting that the Soviet dictatorship was as “rigid” as the Nazi, but that Hitlerism was more dangerous to humanity and to religion than was Communism. The Pope was little influenced by this view, and his doctrinal expert, Monsignor Domenico Tardini, bluntly stated that Communism was and always would be antireligious and militaristic and told the Pope privately that Roosevelt was apologizing for Communism. The Vatican did respond to Roosevelt a bit by restating doctrine in such a way as to enable Catholics to make a distinction between aiding Russians and aiding Communism. Roosevelt also tried to induce Moscow to relax its antireligious posture, but with little effect.

Clearly the great opportunist was having little impact on the great doctrinaire. But if the President hardly was leading a holy crusade for a full partnership of the antifascist forces, he was at least removing some of the roadblocks and allowing events to exercise their sway. Congress defeated moves to bar the President from giving Lend-Lease aid to Russia, and at the end of October the President without fanfare told Stalin that he could have one billion dollars in supplies. Yet the President paid a price for this success. He and his colleagues had to stress not the great ideals of united nations but the expedient need to help keep the Russian armies in the fight and thus to make American military intervention less necessary. Aid was extended for crass reasons of self-interest. The only link between Americans and Russians was a common hatred and fear of Nazism.

Stalin was not deceived. He wrote to Churchill in early November that the reasons for the lack of clarity in the relations of their nations were simple: lack of agreement on war and peace aims, and no second front. He could have said the same to Roosevelt.

The whole anti-Axis coalition, indeed, was in strategic disarray by late fall of 1941, even while it was co-operating on a host of economic, military, and diplomatic matters. Churchill was almost desperate over Washington’s stubborn noninvolvement. He still had serious doubts about Russia’s capacity to hold out; he had to face the nightmarish possibility of Britain alone confronting a fully mobilized Wehrmacht. As it was, he had to share American aid with Russia, and while he was eager to do anything necessary to keep the Bear fighting, he found it surly, snarling, and grasping. He still feared a Nazi invasion of Britain in the spring, and he was trying to build up his North African strength for an attack to the west. Stalin was always a prickly associate. A mission to Moscow led by Lord Beaverbrook and Averell Harriman had established closer working relations with the Soviets, but no mission could solve the basic problem that Russia was taking enormous losses while only a thin trickle of supplies was arriving through Archangel, Vladivostok, and Iran. As for China, which was at best third on the waiting list for American aid, feeling in Chungking ranged between bitterness and defeatism.

So if Roosevelt was stranded in the shoals of war and diplomacy, he was no worse off than the other world leaders in 1941. All had seen their earlier hopes and plans crumble. Hitler had attacked Russia in the expectation of averting a long war on two fronts; now he was engaged in precisely that. Churchill had hoped to gain the United States as a full partner, but had gained Russia; he had wanted to take the strategic initiative long before, but had failed; he doubted that Japan would take on Britain and America at the same time, but events would prove him wrong. Stalin had played for time and lost; now the Germans, fifty miles west of Moscow, were preparing their final attack on it.

All the global forces generated by raw power and resistance, by grand strategies and counter-strategies, by sober staff studies and surprise blows—all were locked in a tremulous world balance. Only some mighty turn of events could upset that balance and release Franklin Roosevelt from his strategic plight.

On November 1, 1941, the new leaders of Japan met to decide the issues they had debated since assuming office two weeks before. Should they “avoid war and undergo great hardships”? Or decide on war immediately and settle matters? Or decide on war but carry on diplomacy and war preparations side by side? These were the alternatives as Premier Tojo framed them for his colleagues: Foreign Minister Togo, Finance Minister Okinori Kaya, Navy Minister Shigetaro Shimada, Navy Chief of Staff Osami Nagano, Planning Board Director Teiichi Suzuki. Also present were members of the military “nucleus”: Army Chief of Staff General Sugiyama, the Army Vice Chief of Staff, the Navy Vice Chief of Staff, and others.

It was a long meeting—seventeen hours—and a stormy one. Pressed by a skeptical Togo and Kaya as to whether the American fleet would attack Japan, Nagano replied, “There is a saying, ‘Don’t rely on what won’t come.’ The future is uncertain; we can’t take anything for granted. In three years enemy defenses in the South will be strong and the number of enemy warships will increase.”

“Well, then,” Kaya said, “when can we go to war and win?”

“Now!” Nagano exclaimed. “The time for war will not come later!”

The discussion went on. Finally it was agreed to pursue war preparations and diplomacy simultaneously. The burning issue was the timing of the two and their interrelation. The early deadline, said Tojo, was outrageous. A quarrel broke out so intense that the meeting had to be recessed; operations officers were called in to consider the timing question from a technical viewpoint. The military chiefs conceded that it would be all right to negotiate until five days prior to the outbreak of war. This would mean November 30.

“Can’t we make it December 1?” asked Tojo. “Can’t you allow diplomatic negotiations to go for even one day more?”

“Absolutely not,” Army Vice Chief of Staff Tsukada said. “We absolutely can’t go beyond November 30. Absolutely not.”

“Mr. Tsukada,” asked Shimada, “until what time on the 30th? It will be all right until midnight, won’t it?”

“It will be all right until midnight.”

Thus, as the army records of this session noted, a decision was made for war; the time for its commencement was set for the beginning of December; diplomacy was allowed to continue until midnight, November 30; and if diplomacy was successful by then, war would be called off. The conference then debated two alternative proposals for negotiation. The crucial point of Proposal A was that Japanese troops could be stationed in strategic areas of China until 1966. Proposal B would largely restore the status quo ante the July freeze: the two nations would undertake not to advance by force in Southeast Asia or the South Pacific; Japanese troops in Indochina would move to the northern part of the country; the United States would help Japan obtain resources in the Dutch East Indies and would supply annually a million tons of oil; the United States would not obstruct “settlement of the China incident.” The military preferred A because it posed the crucial question of China and would settle it quickly one way or the other—but fearing that Tojo might resign and topple the whole Cabinet, they agreed also to support the broader, but hardly less severe, terms of B.

On November 5 Tojo presented this consensus to an imperial conference at the palace. All agreed that if the diplomats could not settle matters by December 1, Japan would go to war regardless of the state of negotiations at that time. The Emperor had nothing to offer on this occasion—not even verse.

It was another major step toward war, but the Japanese were still following their two-pronged approach. Nomura continued his discussions with Roosevelt and Hull and continued to receive sermons of peace, stability, and order in the Pacific. Roosevelt was still playing for time, but Hull’s rigidity on principle was hardening as a result of MAGIC intercepts of Japanese coded messages indicating the dominance of the military and its timetable. Each side was now looking to its allies. Japan, which had edged away from Berlin as the Wehrmacht slowed in Russia, was now drawing closer to its partner in case of need. Hull told Nomura that he might be lynched if he made an agreement with Japan while Tokyo had a definite obligation to Germany.

The paramount issue was still China. When Nomura came back to the White House on November 17, this time with Saburo Kurusu, who had come from Tokyo as special ambassador to expedite the discussions, Roosevelt again urged the withdrawal of Japanese troops from China; once the basic questions were settled, he said, he would be glad to “introduce” Japan and China to each other to settle the details. After Kurusu failed to budge on this question Roosevelt retreated to homilies; there were no long-term differences preventing agreement, he said.

Empty words. It was becoming increasingly clear that there were few misunderstandings between the two countries, only differences. Despite much confusion the two governments understood each other only too well. Their interests diverged. They could not agree. When the Tokyo diplomats in desperation presented Proposal B, now softened a bit but still providing an end to American aid to China, Hull dismissed the contents as “of so preposterous a character that no responsible American official could ever have accepted them”—even though Tokyo meant them only as a stopgap, and Stark and Marshall found them acceptable as a way to stave off war.

Word arrived from Chungking that Chiang was completely dependent on American support and was agitated about reports of temporizing in Washington.

Undaunted, Roosevelt by now was working up a truce offer of his own. Around the seventeenth he had penciled a note to Hull:

6 Months

1. U.S. to resume economic relations—some oil and rice now—more later.

2. Japan to send no more troops to Indo-China or Manchurian border or any place south (Dutch, Brit, or Siam).

3. Japan to agree not to invoke tripartite pact if U.S. gets into European war.

4. U.S. to introduce Japs to China to talk things over but U.S. take no part in their conversations. Later on Pacific agreements.

This was Roosevelt’s most ambitious specific truce formula in the dying days of peace, and its short life and early death summed up the intractable situation. Hull combined Roosevelt’s plan with other proposals, American and Japanese, and cut the period to three months. On the twenty-second a message from Tokyo to Nomura and Kurusu was intercepted; it warned that in a week “things are automatically going to happen.” Cabling Churchill the essence of the American proposal, Roosevelt added that its fate was really a matter of internal Japanese politics. “I am not very hopeful and we must all be prepared for real trouble, possibly soon.” On the same day the Chinese Ambassador, Dr. Hu Shih, objected vigorously to letting Tokyo keep 25,000 men in northern Indochina. Chiang was wondering, he said, whether Washington was trying to appease Japan at the expense of China. The Dutch and the Australians were dubious about concessions.

Churchill was worried, too. “…Of course, it is for you to handle the business,” he cabled to Roosevelt, “and we certainly do not want an additional war. There is only one point that disquiets us. What about Chiang Kai-shek? Is he not having a very thin diet? Our anxiety is about China.” If it collapsed, their joint dangers would enormously increase. “We are sure that the regard of the United States for the Chinese cause will govern your action. We feel that the Japanese are most unsure of themselves.” Perhaps Roosevelt would have persevered. But on the morning of the twenty-sixth Stimson telephoned him an intelligence report of Japanese troop movements heading south of Formosa.

December 2,1941, Rollin Kirby, reprinted by permission of the New York Post

The President fairly blew up—“jumped up into the air, so to speak,” Stimson noted in his diary. To the President this changed the whole situation, because “it was evidence of bad faith on the part of the Japanese that while they were negotiating for an entire truce—an entire withdrawal (from China)—they should be sending their expedition down there to Indo-China.” Roosevelt’s truce formula died that day. In its stead Hull drew up a ten-point proposal that restated Washington’s most stringent demands.

The whole matter had been broken off, Hull told Stimson. “I have washed my hands of it and it is now in the hands of you and Knox—the Army and the Navy.” Shortly Stimson phoned the President again; the time had come, they agreed, for a final alert to MacArthur.

Diplomatic exchanges continued for a while, like running-down tops. On November 26 Hull presented Nomura and Kurusu with his ten points; Kurusu said that Japan would not take its hat off to Chiang—the proposals were not even worth sending to Tokyo. November 27—the President warned the two envoys at the White House that if Tokyo followed Hitlerism and aggression he was convinced beyond any shadow of a doubt that Japan would be the ultimate loser; but he was still ready to be asked by China and Japan to “introduce” them for negotiations, just as he had brought both sides together in strike situations. November 28—Nomura and Kurusu received word from Tokyo that they would soon have an elaboration of its position and the discussions would then be “de facto ruptured”; but they were not to hint of this. November 29 (Tokyo time) at the liaison conference: Togo: “Is there enough time left so that we can carry on diplomacy?” Nagano: “We do have enough time.” Togo: “Tell me what zero hour is. Otherwise I can’t carry on diplomacy.” Nagano: “Well, then, I will tell you. The zero hour is”—lowering his voice—“December 8.” November 30—at Warm Springs for a belated Thanksgiving with the patients, the President took a telephone call from Hull urging him to return to Washington because a Japanese attack seemed imminent; he left immediately. December 1—Premier Tojo at the Imperial Conference: “At the moment our Empire stands at the threshold of glory or oblivion.” The Chiefs of Staff asked the Emperor’s permission to make war on X day. Hirohito nodded his head. He seemed to the recorder to be at ease. December 2—Roosevelt, through Welles, demanded of Nomura and Kurusu why their government was maintaining such large forces in Indochina. December 3—Tokyo handed Berlin and Rome its formal request for intervention; Mussolini professed not to be surprised considering Roosevelt’s “meddlesome nature.” December 4—the President concluded a two-hour conference with congressional leaders with the request that Congress not recess for more than three days at a time. December 5—some in the White House were still considering reviving the ninety-day truce proposal, if only to gain time. December 6—Roosevelt worked on an arresting message to Hirohito urging a Japanese withdrawal from Indochina and the dispelling of the dark clouds over the Pacific.

Almost a century before, he reminded the Emperor, the President of the United States had offered the hand of friendship to the people of Japan and it had been accepted. “Only in situations of extraordinary importance to our countries need I address to Your Majesty messages on matters of state.” Such a time had come. The President dwelt on the influx of Japanese military strength into Indochina. The people of the Philippines, the East Indies, Malaya, Thailand were alarmed. They were sitting on a keg of dynamite. The President offered to gain assurances from these peoples and even from China—and offered those of his own nation—that there would be no threat to Indochina if every Japanese soldier or sailor were to be withdrawn therefrom. Clearly the President was not engaging in serious negotiation here; it was one more effort to stall off a showdown.

“I address myself to Your Majesty at this moment in the fervent hope that Your Majesty may, as I am doing, give thought in this definite emergency to ways of dispelling the dark clouds….”

It was like a gigantic frieze in which all the actors move and yet there is no motion. While diplomats were deadlocked, however, the military was acting with verve and precision. In September Japanese carriers and their air groups had started specific training for Pearl Harbor, with the help of a mock-up as big as a tennis court. On October 5 one hundred officer pilots of the carrier air groups got the heady news that they had been chosen to destroy the American fleet in Hawaii early in December. On November 7 Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto set December 8 as the likely date because it was a Sunday. During mid-November the striking force of six carriers, two battleships, two cruisers, and nine destroyers put out from Kure naval base and rendezvoused in the Kuriles. On November 25 Yamamoto, from his flagship in the Inland Sea, ordered the advance into Hawaiian waters, subject to recall. On December 2 he broadcast the phrase “NIITAKE-YAMA NOBORE” (Climb Mount Niitaka)—the code for PROCEED WITH ATTACK! Meantime, other Japanese fleet units and scores of transports were moving into positions throughout the southern seas.

And Roosevelt? In this time of diplomatic stalemate and military decision he was still waiting, now almost fatalistically. “It is all in the laps of the gods,” he told Morgenthau on December 1. As late as December 6 he would tell Harold Smith that “we might be at war with Japan, although no one knew.” The President was pinioned between his hopes of staving off hostilities in the Pacific and his realization that the Japanese might not permit it; between his promise to avoid “foreign” wars and his deepening conviction that Tokyo was following Nazi ways and threatened his nation’s security; between his moral and practical desire to stand by the British and Dutch and Chinese and his worry that thereby he might be directly pulled into a Pacific war. He was pinioned, too, between people—between Hull, with his curious compound of moralizing and temporizing, and the militants, such as Morgenthau, who was pleading with the President not to desert China, and Ickes, who was ready to resign if he did; between the internationalists in the great metropolitan press and the isolationists in Congress; even between the “pro-Chinese” in the State Department and the “pro-Japanese,” including Grew, and finally between the polled citizens who said he was going too far in intervening abroad and those who said he was doing too little.

Pinioned but not paralyzed. The President’s mind was taken up by probabilities, calculations, guesses, alternatives. By the early days of December he felt that a Japanese attack south was probable. It was most likely to come, he thought, in the Dutch East Indies; next most likely in Thailand, somewhat less likely in the Philippines, and least probable—to the extent he thought about it all—in Hawaii. If the Japanese attacked British territory he would give Churchill armed support, the nature and extent depending, much as in the Atlantic, on the circumstances; if the Japanese attacked Thailand or the East Indies, Britain would fight and Roosevelt would provide some kind of armed support; if the Japanese attacked China from Indochina, he would simply step up aid to Chungking.

At this penultimate hour Roosevelt was extending his Atlantic strategy to the Pacific. It was not a simple matter of “maneuvering the Japanese into firing the first shot,” for the Japanese were probably going to fire the first shot; the question was where the United States could respond, how quickly, and how openly and decisively. What Roosevelt contemplated was a replica of his support of Britain in the Atlantic, a slow stepping-up of naval action in the southern seas, with Tokyo bearing the responsibility for escalation. He had asked and received permission from the British and Dutch to develop bases at Singapore, Rabaul, and other critical points—a repetition of his acquisition of Atlantic bases the year before. He did not concentrate on the Atlantic at the expense of the Pacific; he did not leave things unduly to Hull. He could not; the pressures were too heavy. But he did apply to the Pacific the lessons of his experience in the Atlantic.

It was a dangerous transfer, for it fostered Roosevelt’s massive miscalculation as to where the Japanese would strike first. Since he had reason to believe that he was confronting another Hitlerite nation in the East, he assumed that Tokyo would follow the Nazi method of attacking smaller nations first and then isolating and encircling the larger ones. He told reporters, off the record, on November 28 that the Japanese control of the coasts of China and the mandated islands had put the Philippines in the middle of a horseshoe, that “the Hitler method has always been aimed at a little move here and a little move there,” by which complete encirclement was gained. “It’s a perfectly obvious historical fact today.” But Roosevelt was facing a different enemy, with its own tempo, its own objectives—and its own way with a sudden disabling blow.

When general plans fail, lesser plans, miscalculations, technical procedures, and blind chance have a wider play. During the evening of December 6 the Japanese carriers reached the meridian of Oahu, turned south, and amid mounting seas sped toward Pearl Harbor with relentless accuracy. In Tokyo a military censor routinely held up the message from Roosevelt to Hirohito. If it had been in plain English he would not have dared hold up such an awesome communication; if it had been in top-priority code he would not have known enough to; but Roosevelt had sent it in gray code to save time, and it finally arrived too late. In the Japanese Embassy in Washington a many-part message began to come in from Tokyo; the parts were sent down to the coding room, but the cipher staff drifted off to a party, the fourteenth section was delayed, and the embassy closed down for the night. At the War and Navy Departments, signals experts received the first thirteen parts through their MAGIC intercept and swiftly decoded them; copies were rushed to the White House and to Knox and Navy chiefs, but not to Admiral Stark, who was at the theater, nor—inexplicably—to General Marshall, who was understood to be in his quarters.

At 9:30 P.M. a young Navy officer brought the thirteen parts to the oval study. The President was going over stamps, meanwhile chatting with Hopkins, who was sitting on the sofa. The President read rapidly through the papers. All day he had been receiving reports of Japanese convoy and ship movements in the Southwest Pacific.

“This means war,” the President said as he handed the sheaf to Hopkins.

For a few moments the two men talked about likely Japanese troop movements out of Indochina. It was too bad, Hopkins said, that the Japanese could pick their own time and America could not strike the first blow.

“No, we can’t do that,” Roosevelt said. “We are a democracy and a peaceful people.” Then he raised his voice a bit.

“But we have a good record.”

In the dark early-morning hours scores of torpedo planes, bombers, and fighters soared off the pitching flight decks of their carriers to the sound of “Banzai!” Soon 183 planes were circling the carriers and moving into formation. At about 6:30 they started south. Emerging from the clouds over Oahu an hour later, the lead pilots saw that everything was as it should be—Honolulu and Pearl Harbor bathed in sunlight, quiet and serene, the orderly rows of barracks and aircraft, the white highway wriggling through the hills—and the great battlewagons anchored two by two along the mooring quays of Pearl Harbor. It was a little after 7:30 A.M., December 7, 1941. It was the time for war.