THE PRESIDENT HAD RETURNED home from Teheran to an embittered capital. All the old simmering issues seemed to be coming to a boil. Joseph Guffey, the aged New Deal war horse, rose in the Senate to castigate the “unholy alliance” of Old Guard Republicans under Joe Pew and of Southern Democrats under Harry Byrd. In reply, his foes threatened to organize a new Southern party that would hold a balance of power between the two major parties. In the House, John Rankin, of Mississippi, pointedly read off the Jewish names of New Yorkers supporting a soldiers’-vote bill. Secretary of Interior Ickes charged over a nationwide radio hookup that the “four lords of the press”—Hearst, McCormick, and the two Pattersons—hated Roosevelt and Stalin so bitterly that they would rather see Hitler win the war than be defeated by “a leadership shared in by the great Russian and the great American.”

“There is terrific tension on the Hill,” Budget Director Smith noted. “People who have been friends for years are doing the most erratic things.” A leading politician said privately: “I haven’t an ounce of confidence in anything that Roosevelt does. I wouldn’t believe anything he said.”

Seldom had race feeling been so conspicuous in the capital. Indignation greeted the news that 16,000 “disloyal” Japanese had rioted at the Tule Lake concentration camp. The Senate killed a federal aid-to-education bill when Republicans adroitly hitched on an antidiscrimination provision. Railroad employers and unions alike defied an FEPC order barring discrimination against Negro firemen. Not since Reconstruction, the Nation observed, had sectional feeling run so high in the halls of Congress.

“The President has come back to his own Second Front,” Max Lerner wrote. “We shall need to build another bridge of fire, not to link in with our Allies but to unite us with ourselves, and to span the fissure within our own national will.”

The center of the storm seemed as calm as ever. He had got the impression on returning that there was a terrible mess in Washington, the President observed mildly to the Cabinet. Nor did he betray any worry. “There he sat,” reported the New Republic’s TRB, “at his first press conference after his five weeks on tour-Churchill sick; inflation controls going all to pot; the Democratic party at sixes and sevens; a rail strike threatened; selfish goals sought by labor and farmers and business; ignoble motives imputed to every public act of every public man; the world a global mess—and there he sat, bland and affable, in his special chair, puffing imperturbably on an uptilted cigarette and welcoming old friends.”

Roosevelt was not as imperturbable as he appeared. He was entering the new year like a tightrope walker starting out over Niagara. Monumental questions were hanging in the balance—not only the war economy, his electoral standing with the voters, the cross-channel invasion, the invasion routes to Japan, but also his whole strategy of war and peace. He was following a precarious middle way. He was trying to establish close rapport with Russia and at the same time follow an Atlantic First strategy depending on the closest relations with the British. He was trying to help make China a great nation in war and peace while putting it far down the priority list of military aid and political influence. He was trying to establish a new and better League without alienating the isolationists. He was calling for freedom for all peoples but deferring to the British in India and the Moslems in the Near East. He was demanding unconditional surrender but dealing with Darlans and Badoglios.

He had said that “magnificent idealism” was not enough; neither was manipulation or expediency. How he balanced and interlinked the demands of his faith and the necessities of the moment would be the great test of Franklin Roosevelt in 1944.

After seeing soldiers stuck in lonely outposts in Iran and stretched out on hospital cots in Sicily, the President was indignant about the attitudes he found at home—complacent expectations of an early victory, isolationists spreading suspicion about the Allied nations, noisy minorities demanding special favors, profiteers, selfish political interests, and all the rest. He decided to declare war on these elements in his State of the Union message—indeed, to make a dramatic reassertion of American liberalism even at the height of war.

But first he indulged in one of those baffling sidesteps that often had accompanied, and camouflaged, a major Rooseveltian action. To a reporter who had tarried a bit after a press conference the Chief Executive had complained that he wished the press would not use that term “New Deal,” for there was no need of a New Deal now. At the next press conference reporters pressed him for an explanation. The President assumed a casual air, as though it was all so obvious; some people, he said, just had to be told how to spell “cat.” He described how “Dr. New Deal” had treated the nation for a grave internal disorder with specific remedies. He quoted from a long list Rosenman had put together of New Deal programs. But after his recovery, he went on, the patient had a very bad accident—“on the seventh of December, he was in a pretty bad smashup.” So Dr. New Deal, who “didn’t know nothing” about legs and arms, called in his partner, “who was an orthopedic surgeon, Dr. Win-the-War.”

“Does that all add up to a fourth-term declaration?” a brash reporter asked.

“Oh, now, we are not talking about things like that now. You are getting picayune….”

“I don’t mean to be picayune,” the reporter went on, “but I am not clear about this parable. The New Deal, I thought, was dynamic, and I don’t know whether you mean that you had to leave off to win the war and then take up again the social program, or whether you think the patient is cured?”

The President answered with a confusing analogy of post-Civil War policy. Then he insisted again: the 1933 program was a program to meet the problems of 1933. In time there would have to be a new program to meet new needs. “When the time comes…When the times comes.”

There’s an Odd Family Resemblance Among the Doctors

December 30, 1943, C. K. Berryman, courtesy of the Washington (D.C.) Star

The creator of the New Deal had killed it, the conservative press exulted.

Two weeks later Roosevelt gave the most radical speech of his life. He chose his annual State of the Union message as the occasion. Early in January he had come down with the flu, but he labored over draft after draft while Rosenman and Sherwood sat by his bed. He had not recovered enough to deliver the message to Congress in person, but he insisted on giving it as a fireside chat in the evening for fear that the papers would not run the full text.

The President lashed out at “people who burrow through our Nation like unseeing moles…pests who swarm through the lobbies of Congress and the cocktail bars of Washington…bickering, self-seeking partisanship, stoppages of work, inflation, business as usual…the whining demands of selfish pressure groups who seek to feather their nests while young Americans are dying.”

Once again he asked Congress to adopt a strong stabilization program. He recommended:

“1. A realistic tax law—which will tax all unreasonable profits, both individual and corporate, and reduce the ultimate cost of the war to our sons and daughters….

“2. A continuation of the law for the renegotiation of war contracts—which will prevent exorbitant profits and assure fair prices to the Government….

“3. A cost of food law—which will enable the Government (a) to place a reasonable floor under the prices the farmer may expect for his production; and (b) to place a ceiling on the prices a consumer will have to pay for the food he buys….

“4. Early reenactment of the stabilization statute of October, 1942….We cannot have stabilization by wishful thinking. We must take positive action to maintain the integrity of the American dollar.

“5. A national service law—which, for the duration of the war, will prevent strikes, and, with certain appropriate exceptions, will make available for war production or for any other essential services every able-bodied adult in the Nation.”

Then came the climax of the address:

“It is our duty now to begin to lay the plans and determine the strategy for the winning of a lasting peace and the establishment of an American standard of living higher than ever before known. We cannot be content, no matter how high that general standard of living may be, if some fraction of our people—whether it be one-third or one-fifth or one-tenth—is ill-fed, ill-clothed, ill-housed, and insecure.

“This Republic had its beginning, and grew to its present strength, under the protection of certain inalienable political rights—among them the right of free speech, free press, free worship, trial by jury, freedom from unreasonable searches and seizures. They were our rights to life and liberty.

“As our Nation has grown in size and stature, however—as our industrial economy expanded—these political rights proved inadequate to assure us equality in the pursuit of happiness.

“We have come to a clear realization of the fact that true individual freedom cannot exist without economic security and independence. ‘Necessitous men are not free men.’ People who are hungry—people who are out of a job—are the stuff of which dictatorships are made.”

The President was now speaking with great deliberateness and emphasis. The italics were not in his text, but in his delivery.

“In our day these economic truths have become accepted as self-evident. We have accepted, so to speak, a second Bill of Rights under which a new basis of security and prosperity can be established for all—regardless of station or race or creed.

“Among these are:

“The right to a useful and remunerative job in the industries or shops or farms or mines of the Nation;

“The right to earn enough to provide adequate food and clothing and recreation;

“The right of farmers to raise and sell their products at a return which will give them and their family a decent living;

“The right of every businessman, large and small, to trade in an atmosphere of freedom from unfair competition and domination by monopolies at home or abroad;

“The right of every family to a decent home;

“The right to adequate medical care and the opportunity to achieve and enjoy good health;

“The right to adequate protection from the economic fears of old age and sickness and accident and unemployment;

“And finally, the right to a good education.

“All of these rights spell security. And after this war is won we must be prepared to move forward, in the implementation of these rights, to new goals of human happiness and well-being….”

In its particulars the economic bill of rights was not very new. It was implicit in the whole sweep of Roosevelt’s programs and proposals during the past decade; it was Dr. New Deal himself suddenly called back into action. But never before had he stated so flatly and boldly the economic rights of all Americans. And never before had he linked so explicitly the old bill of political rights against government to the new bill of economic rights to be achieved through government. For decades the fatal and false dichotomy—liberty against security, freedom against equality—had deranged American social thought and crippled the nation’s capacity to subdue depression and poverty. Now Roosevelt was asserting that individual political liberty and collective welfare were not only compatible, but they were mutually fortifying. No longer need Americans swallow the old simplistic equation the more government, the less liberty. The fresh ideas and policies of Theodore Roosevelt and of Robert La Follette, of Woodrow Wilson and of Al Smith, of the earlier Herbert Hoover and of George Norris, nurtured in days of muckraking and protest, evoked by depression, hardened in war, came to a clear statement in this speech of January 11, 1944.

And this appeal fell with a dull thud into the half-empty chambers of the United States Congress.

“He’s like a king trying to reduce the barons,” Senator Wheeler had cried out against Roosevelt in the early New Deal years. He himself was the baron of the Northwest; Huey Long, the baron of the South; Roosevelt had once been just a baron, too. Ten years later most of the old barons, including Wheeler himself, dominated the political life of Capitol Hill. But now they were less the lords of regions—except, always, the South—than masters of procedure, evokers of memories, voices of ideology—and contrivers of deadlock. Power holding on Capitol Hill had changed little since before Pearl Harbor. There was the ancient and ailing Carter Glass, who, with his protégé Harry Byrd, still ran the Virginia Democratic party; Gerald Nye, as forceful, shrewd, and fundamentally isolationist as ever; Bennett Champ Clark, rotund and forensic, a spokesman for veterans; the stocky, smooth-faced Robert La Follette, less isolationist than his father but wary of Roosevelt’s foreign commitments; Hiram Johnson, seventy-seven, a true baron of the West, a bit feeble now but still a commanding presence with his noble features and snow-white hair. There were a brace of ambitious Republicans: Robert Taft, already high in the Senate establishment for a first-termer, dry, competent, assured; Arthur Vandenberg, now midway in his long, troubled retreat from isolationism, looking both wise and naïve , with his owlish little features setting off a big round face; the handsome, towering Henry Cabot Lodge, grandson of the great isolationist and a living invocation of the battles of 1919, a soldier who would soon go off to the wars again. There was a handful of vigorous internationalists: Warren Austin, of Vermont, Joseph H. Ball, of Minnesota, Harold H. Burton, of Ohio. Many an internationalist Democrat was there, too: Alben Barkley, Abe Murdock, of Utah, Theodore Green, James E. Murray, of Montana, Harry Truman, and others. But the Democrats were divided in war as in peace. Walter George, Kenneth McKellar, of Tennessee, Theodore G. Bilbo, of Mississippi, William B. Bankhead, of Alabama, E. D. (“Cotton Ed”) Smith, of South Carolina, and others were guardians of the South, lords of their committees, and as a group not dependably internationalist.

One way or the other Roosevelt had taken the measure of such men, Republican and Southern Democrat alike. But in early 1944 the rules of the game were different because the stakes had drastically altered. The issue was no longer welfare or domestic reform or economic policy, for which presidential pressure, persistence, and politicking could be counted on to bring a satisfactory if delayed victory. The President’s adversaries on the Hill now had the power to deny his supreme ambition—to lead the United States into an effective world-security organization.

Ridden by the memory of Wilson’s defeat, Roosevelt had been proceeding all through 1943 with almost fanatical cautiousness on postwar organization. He had let Hull and a group of State Department experts move ahead quietly with planning for postwar peace and security. He had let Willkie and other internationalist Republicans proclaim the postwar security underpinnings of “one world.” In Congress the internationalist Democrats were restive. J. William Fulbright, a low-ranking member of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, urged the President to support his resolution favoring international machinery with power adequate to establish and to maintain a just and lasting peace, and for United States participation therein. He had always felt, he wrote, that the President’s success had been largely due “to your courage in boldly taking the lead” on troublesome problems. Roosevelt would not take the lead on even such an innocuous resolution, but after conferring with Hull he told Fulbright that he favored action on his resolution if it gained wide backing and if no prejudicial amendments were tacked on it.

As usual Roosevelt’s cautiousness was well calculated. His views on postwar organization had developed slowly before Teheran; he still favored Big Four domination and regional security organization. Hull and his State Department planners were strong for one universal organization. Questions were already arising—of a Big Power veto, of the method of representing nations, of a world-security force, of the relation between postwar peace treaties and the establishment of a permanent world organization—questions that aroused disturbing echoes of the controversies that had done the League to death.

Roosevelt wanted to still those echoes. The history-minded President was, indeed, so worried about improper parallels being drawn between 1919 and 1943 that he asked Hull to postpone publication of notes of conversations among Wilson, Lloyd George, and Clemenceau; such notes should not have been made in the first place, he added. He was resolved that any congressional planning for a new League must be very gradual and wholly bipartisan. Above all, discussion must not get bogged down in minor details. But there was considerable feeling in the Senate that specifics were the crucial matter. Willkie Republicans wanted a more explicit plan. When the Senate Foreign Relations Committee reported out the Connally Resolution, calling for United States participation, through its constitutional processes, in the “establishment and maintenance of international authority with power to prevent aggression and to preserve the peace of the world,” the President favored an even more general statement.

“Mr. President,” he was asked at a press conference late in October 1943, “does the Committee Resolution reported out by the Senate Foreign Relations Committee meet that specification [of generality]?”

“That’s the whole trouble,” Roosevelt answered. “Now you put your finger right on it. How could I answer that question? I couldn’t. Now you are getting down to specific language. You and I could sit down, if we were the dictators of the world, and work out some language that you and I thought was 100 per cent. And then Earl Godwin would come in and give us something that was better.”

“Earl Godwin thinks that it does,” Godwin said, amid laughter. “Now, if it’s just a matter of words, it’s sort of silly to take up time—”

“Well,” the President interrupted, “I think the Senate has every right to talk about it just as long as they want.”

“Exactly, sir, we shouldn’t say anything else. But suppose the Senate had adopted the Resolution, which it may at any moment, and you may be over in Europe, will the United States or will the President of the United States feel bound by this kind of Resolution?”

“That’s a difficult thing to say. I might not like it.”

“Well, it’s an expression of the Senate. It isn’t the ratification of anything.”

The President would not show his hand.

“Well, if the general sentiment is all right that’s fine. I have told you what the general sentiment I think ought to be. This country wants to stop war….”

By the end of 1943, however, things were falling into place for Roosevelt. The Republicans at Mackinac had, in the words of Vandenberg, who had exerted skillful conciliatory leadership, “put down in black and white the indispensable doctrine that Americans can be faithful to the primary institutions and interests of our own United States and still be equally loyal to the essential postwar international co-operations which are required to end military aggression for keeps….” Hull had found in Moscow, as Roosevelt had in Teheran, considerable convergence among the Big Three on postwar security policy. Always flexible on ways and means, the President himself had shifted from a regional emphasis to Hull’s universalism.

Roosevelt was also heartened by the the success of international wartime programs and institutions that would undergird postwar co-operation. Lend-Lease, the Combined Chiefs of Staff and its vast Anglo-American supporting and planning machinery, international agricultural and commodity programs, world-wide resource allocation, technical and scientific co-operation—all these activities, and the institutions that embodied and expanded them, appealed to Roosevelt’s preference for practical co-operation and progress without labels and controversy. In November he signed an agreement establishing the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration. “As in most of the difficult and complex things of life,” he said on that occasion, “Nations will learn to work together only by actually working together.”

By 1944 the time had come to move ahead on more definite postwar security planning. During January the President went over a State Department paper embodying the work of its experts. On February 3 he gave Hull formal word to go ahead with his planning for the United Nations on the basis of the State Department proposals, which would later become, with little change, the administration’s proposals to the Dumbarton Oaks Conference. But not for a moment did Roosevelt forget the potential role of the barons on the Hill—or the ambitions and passions that might be aroused by the November elections.

Despite Roosevelt’s talk about keeping issues “out of politics,” nothing important could be insulated from the pressures of campaign year 1944. Barkley, Taft, Nye, and a score of other notable Senators would be up for re-election. So would 435 members of the House of Representatives. And so would the President—perhaps. Nothing at this time could have aroused campaign sensitivities more acutely—along with ideological feelings about states’ rights, fair play, GI’s, the poll tax—than the question of the servicemen’s vote.

Late in January the President put the issue directly before Congress. The people, he said, feared that the vast majority of the eleven million servicemen would be deprived of their right to vote in the fall elections. Men stationed all over the world could not comply with the different voting laws of the forty-eight states. A federal absentee-balloting act passed in September was an advance, but a small one; only 28,000 servicemen had voted that year. A bill endorsed by the Senate in December 1943 “recommending” to the states that they pass absentee-ballot legislation was meaningless—a fraud to the servicemen, a “fraud upon the American people.” He asked Congress to enact a pending administration bill that would provide for quick and simple voting for federal candidates by name or—if the name of the candidate was still unknown—simply by checking the party preferred.

“Our millions of fighting men do not have any lobby or pressure group on Capitol Hill to see that justice is done for them,” the President added pointedly. As Commander in Chief he was expressing their resentment for them. And, admitting that as Chief Executive he had no right to interfere in legislative procedures, as an “interested citizen” he demanded that every member in Congress stand up and be counted in a roll-call vote rather than take cover in a voice vote.

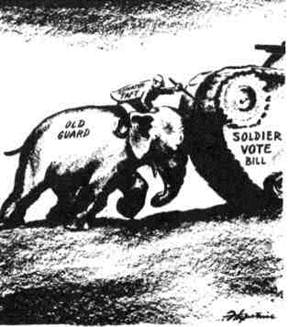

The message hit Congress like a declaration of war. The 1944 campaign was under way, the Commander in Chief himself a likely candidate for President. His face red and his arms flailing, Senator Taft charged that Roosevelt was planning to line up soldiers for the fourth term as WPA workers once were marched to the polls.

January 28, 1944, Daniel R. Fitzpatrick, St. Louis Post-Dispatch

GOING UP AGAINST SOMETHING

“That’s okay, Joe—at least we can make bets.”

Drawing copyrighted 1944 by United Features Syndicate, Inc., reproduced by courtesy of Bill Mauldin

Privately Republicans and Southern Democratic Senators poured out their feelings. “Roosevelt says we’re letting the soldiers down,” a Senator said. “Why, God damn him. The rest of us have boys who go into the Army and Navy as privates and ordinary seamen and dig latrines and swab decks and his scamps go in as lieutenant colonels and majors and lieutenants and spend their time getting medals in Hollywood. Letting the soldiers down! Why, that son of a bitch…”

Roosevelt was the issue. If he would only eliminate himself as a fourth-term candidate, Republican Senator Rufus C. Holman, of Oregon, announced, the bill would pass. Democratic Senator Murdock answered mockingly: “I know it is the prayer in his heart, and it is the prayer in the heart of every other good, old, stand-pat Republican in the United States today…that Franklin D. Roosevelt would eliminate himself from politics and give them at least a shadow of a chance to bring in the Grand Old Party again. But I say to them…the American people still want Roosevelt.” At this the Senate gallery broke into applause and jeers.

Debate took an uglier turn in the House. Southerners feared that a soldiers’-vote act would override the poll tax and enable Negroes to vote. “Now who is behind this bill?” Rankin demanded of the House. “The chief publicist is PM, the uptown edition of the Communist Daily Worker that is being financed by the tax-escaping fortune of Marshall Field III, and the chief broadcaster for it is Walter Winchell—alias no telling what.”

“Who is he?” prompted a conservative Republican.

“The little kike I was telling you about the other day, who called this body the ‘House of Reprehensibles.’ ” No one rose to protest, and after Rankin closed with a quavering appeal to the Constitution and states’ rights, scores of Congressmen rose and applauded him.

For weeks the Senate and House worked the bill over, slowly squeezing out its substance. By the time it reached Roosevelt the measure was little more than a shell. The President was so vexed by the confusion and delay wrought by his conservative foes and by the bill’s limited scope that he refused to sign it. Under the bill that became law without his signature, 85,000 servicemen voted in the November election by means of the federal ballot, though a larger number—mainly those still in the country—voted via regular state ballots.

David Lilienthal ran into a special brand of Southern racism and reaction. All through the early months of 1944 he was facing congressional inquisitors hostile to the TVA in general and to him in particular. Rankin had been a champion of the TVA—he claimed, indeed, to be its “co-father”—but in the middle of his struggle Lilienthal learned that the Mississippian was threatening to “blow us out of the water” because the TVA had permitted a Negro girl to take an examination for a clerical position. Lilienthal’s main threat was not Rankin, but McKellar, an aging spoils-man and probably the most parochial member of the Senate. After baiting Lilienthal for hours before the Appropriations Committee, McKellar told the press that he had the “pledge” of the President that Lilienthal would be gotten rid of. Later, Presidential Assistant Jonathan Daniels lunched with Lilienthal and told him that he had mentioned McKellar’s statement to the President, who said that Daniels could tell Lilienthal that the previous spring McKellar had come in with bitter complaints about the TVA Chairman and that the President had replied:

“Well, Kenneth, I have been thinking about getting Lilienthal out of Tennessee myself. I would like to see a Columbia Valley Authority set up in the Northwest, and put Lilienthal in charge of it, since he has done such a good job. But I have never been able to get Congress to pass the bill for a CVA. So if you want to get rid of him, you go back on the Hill and get that bill passed.” How much of this was banter, Lilienthal wondered. But he stayed on.

Like other Presidents, Roosevelt found that his dextrous political management and manipulation could not overcome Congress when great political interests and risks were at stake. National-service legislation in 1944 demonstrated the limits of his influences on the Hill. For many months before Teheran he had vacillated on the matter. Stimson pressed him for a strong proposal to Congress, but WMC and WPB officials were cool to the idea. Baruch argued that the best way to mobilize and allocate manpower was by allocating materials; men would shift to high-priority industries to get jobs. His mind set, but tired of the endless debate, Roosevelt, on returning from Teheran, told Rosenman to draft a proposal for a national-service bill for his State of the Union address, but not to tell a soul about it.

Rosenman was aghast. Not even tell Byrnes or McNutt or Stimson or “Bernie,” men who had been laboring on the problem? No, said his chief, he did not want to argue about it any more. “I want it kept right here in the room just between us boys and Grace.” Byrnes was so indignant when he heard the recommendation over the radio, Rosenman was told, that he stalked into the President’s office and bitterly tendered his resignation; Roosevelt talked him out of it. Stimson was equally surprised, but also so delighted that he forgot to be indignant.

Congress was as cool to national-service legislation in early 1944 as it always had been to proposals that united labor and business in opposition. A gulf yawned between the legislators, sensitive to economic pressures, and Stimson, who saw a moral purpose in the bill transcending even the practical needs of war. A national-service law, he told the Congressmen, was a question of responsibility. “It is aimed to extend the principles of democracy and justice more evenly throughout our population….” Congress did not see it that way; the bill died in committee. Roosevelt had finally come around to Stimson’s point of view. National service transcended politics, he told Congress. “Great power must be used for great purposes.” But he had come to this view late, he had not marshaled his administration behind his position, and he failed to convince the men on the Hill.

The President still met, the first thing on Monday mornings, with the congressional Big Four—Vice President Wallace, Speaker Rayburn, Senate Majority Leader Barkley, House Majority Leader McCormack. Years later Barkley would remember these sessions-Roosevelt sitting in his plain mahogany bed amid a pile of papers, wrapped in an aging gray bathrobe that he refused to give up, puffing on a cigarette through his long uptilted ivory holder, Wallace in turn voluble and quiet, Rayburn laconically sagacious, Barkley himself often speaking for the whole leadership on the Hill.

Late in February 1944 these usually amiable talks took a sharper turn. Even since the previous October, when Morgenthau had presented the President’s stiff revenue proposals to the House Ways and Means Commute, the administration bill had been running-more often crawling—a legislative gantlet. The fiscal committees patiently heard scores of special-interest representatives. Most of the nation’s press opposed the administration’s tax program; the people, as reflected in a Gallup Poll, were as divided as usual. The Ways and Means Committee not only scrapped the Treasury’s program, but also barred Treasury officials from attending its executive sessions. Eventually the committee’s new bill, which would produce barely two billion dollars, was passed by a lopsided vote in the House. The Senate let the bill go over until the next session. In January the President warned that a realistic revenue law would tax all unreasonable profits, both individual and corporate, and that the tax bill then pending did not begin to meet that test. Undismayed, the Senate passed a bill that would raise only a fraction of the 10.5 billion requested by the President and that bristled with what the administration viewed as inequities and favors to special interests.

Congress, it seemed to Roosevelt, was playing with fiscal dynamite. Treasury men estimated that in the fiscal year 1944 income payments to individuals would amount to 152 billion, and that the amount of goods and services available could absorb only about eighty-nine billion of that figure. While the 1943 tax rate would reduce the difference by twenty-one billion, an inflationary gap amounting to forty-two billion would be left to threaten the nation’s stabilization program. War-bond savings and other savings were not expected to reduce this figure enough to forestall the piling up of a dangerous amount of excess income. Taxes were needed for both revenue and stabilization.

The President bespoke his indignation over the tax bill in a bedside conference with the Big Four. All but Wallace urged him to sign it anyway; Roosevelt said he would think it over. A week later he had made up his mind. The administration position had hardened by then. Byrnes originally had favored acceptance of the bill on the ground that if “you asked your mother for a dollar and she gives you a dime” you should go back later for the ninety cents. But Vinson’s and Paul’s arguments swung Byrnes against the bill; and Morgenthau had glumly concluded that the President should let the bill become law without his signature.

When Barkley and his colleagues arrived for the next Monday conference, the President had his tentative veto message written out. He read it to his silent visitors; then Barkley once again sparred with him on the issues. The President was willing to give way on one or two questions, but he was adamant on what he saw as concessions to special interests. Timber was the main case in point. Barkley argued that it should be taxed as capital gains, since it took fifty years to grow a tree for lumber. He grew trees himself, Roosevelt said. Timber should be treated as a crop and therefore as income when sold.

“Well, Mr. President,” Barkley went on, “it’s perfectly obvious that you are going to veto this bill and there’s no use for me to argue with you any longer about it.” Barkley was so depressed that he rode back to the Capitol with Wallace in the latter’s limousine without exchanging a word with him. His dismay turned to indignation next day when he saw the text of Roosevelt’s veto message. New and searing phrases had been added.

He had asked, the President said, for legislation to raise 10.5 billion dollars over present revenues. Persons prominent in public life—everyone knew he was referring mainly to Willkie—had said that his request was too low. The bill from Congress purported to provide 2.1 billion in new revenues but it canceled out automatic increases in the Social Security tax yielding over a billion and granted relief from existing taxes that would cost the Treasury at least 150 million dollars.

“In this respect it is not a tax bill but a tax relief bill providing relief not for the needy but for the greedy.” He listed “indefensible” special privileges to timber and other interests.

“It has been suggested by some that I should give my approval to this bill on the ground that having asked the Congress for a loaf of bread to take care of this war for the sake of this and succeeding generations, I should be content with a small piece of crust. I might have done so if I had not noted that the small piece of crust contained so many extraneous and inedible materials.” He went on to condemn Congress for not simplifying tax laws and returns; the people, he added, were not “in a mood to study higher mathematics.”

For years Barkley had been ridiculed in the press—especially in Time—as a bumbling and spineless flunky of the White House. Now as he read Roosevelt’s biting words he felt personally affronted. He had been a liberal long before the New Deal, he reflected bitterly; he had learned his progressivism at the feet of Woodrow Wilson after coming to Washington from Paducah in 1913. He had gone down the line for Franklin Roosevelt’s program, he had carried the administration’s flag up on the Hill, often with little help from the White House, and now here was this sarcastic message. Barkley had to protect his political situation, too. In Kentucky a Republican trend seemed under way. In the Senate, like other elected leaders before and since, he was caught between members loyal to the President and the anti-Roosevelt Senators clustered in the citadels of power, including the Finance Committee, of which Barkley was a high-ranking member. He checked with his Senate cronies and found them equally aroused. He wanted to denounce the message immediately from the floor, but Chairman George of the Finance Committee was recognized first. Barkley decided to sleep on the matter. Next morning, as he left his apartment he told his wife, an invalid, that he would denounce the President’s veto and resign as Majority Leader. “Go to it, I’m with you,” she said.

Barkley spoke before packed galleries; he did not disappoint his audience. To keep his Democratic credentials, he began with a crack at Willkie—that “up-to-date Halley’s comet darting across the firmament hither and yon to illuminate the heavens with an array of fantastic figures which neither I nor anybody can comprehend.” While he talked, his old foe McKellar, who once had refused to speak to him for weeks even though their seats adjoined, ran copy from page boys who were bringing dictated pages from Barkley’s office. Barkley went on to rebut Roosevelt’s “deliberate and unjustified misstatements” point by point. Roosevelt’s effort to compare his “little pine bushes with a sturdy oak, gum, poplar, or spruce…is like comparing a cricket to a stallion.” The President’s comment about tax relief for the greedy is a “calculated and deliberate assault upon the legislative integrity of every Member of Congress. Other members of Congress may do as they please; but, as for me, I do not propose to take this unjustifiable assault lying down.” He concluded: “If the Congress of the United States has any self-respect left it will override the veto of the President and enact this tax bill into law, his objections to the contrary notwithstanding.” Prolonged applause on the Senate floor, members rising, the reporter noted. Spectators joined in; newsmen dashed from their gallery to their typewriters and telephones.

At this moment Roosevelt was at Hyde Park. He had been quickly informed by Wallace and Byrnes of Barkley’s impending speech and resignation—and he appeared to be unconcerned. He told Byrnes to forget it and “just don’t give a damn…”; he remarked mildly to Hassett that Alben must be suffering from shell shock. Barkley was tired and Mrs. Barkley ill, he said later; it was just a nine-day wonder. When Byrnes pressed him for a conciliatory letter, the President agreed to send one if his War Mobilizer would draft it. Together the President and the former Senator produced a small masterpiece of balm and finesse.

“I sincerely hope,” Roosevelt wrote to Barkley, “that you will not persist in your announced intention to resign as Majority Leader of the Senate. If you do, however, I hope that your colleagues will not accept your resignation; but if they do I hope that they will immediately and unanimously re-elect you.”

Roosevelt’s letter keyed a scenario that had already been planned. Barkley came out of a conference of Senate Democrats to tell reporters, amid exploding flashbulbs, with tears in his eyes, that he had resigned as Majority Leader. He retired to his office while his colleagues deliberated. Suddenly the conference-room door swung open; Tom Connally, resplendent in a long black coat, a boiled white shirt, gold studs, and flowing gray-white hair, burst out, crying, “Make way for liberty! Make way for liberty!” and pushed his way through reporters and cameramen to Barkley’s office. A little procession of Senators followed. A few moments later Barkley was triumphantly escorted back to the conference room, where amid cheers and applause he was unanimously re-elected Majority Leader.

The Senate had had its hour. The nation’s press was delirious. At last the White House errand boy had turned on his master; at last Congress had revolted against the dictator. More satisfaction was to come. The House overrode Roosevelt’s tax veto, 299 to 95; the Senate did the same the next day, 72 to 14. Treasury experts said it was the first revenue act in history to become law over a veto.

The storm, as Roosevelt predicted, blew over in a few days. Barkley, who had seemed self-conscious and uncomfortable as a hero to the Senate barons, wrote the President a cordial note. When he returned to the White House as Majority Leader his role was unchanged. Roosevelt continued to appear undisturbed by the episode. Hassett could detect no bitterness or recrimination—even when the President inspected his Hyde Park timber-cutting operation, which was sending virgin oak direct to shipyards, though possibly it was accidental that photographers were on hand to record the size of the huge trunks. Passage of the tax bill over his veto, Hassett calculated, would save him $3,000 in taxes on his lumbering operations.

Still, things would not be quite the same again. Not only were eight billion dollars of taxes lost, but the orgy of anti-Roosevelt eruptions in Congress and the press left a heavy deposit of bitterness. Western as well as Southern Democratic Senators—Edwin C. Johnson, of Colorado, for one—were coming out publicly against a fourth term. Uneasiness persisted over Roosevelt. Why had he vetoed the bill, knowing he would gain nothing better? And why a veto in such harsh and mocking terms?

The columnists trotted out explanations. It was because Willkie was goading the President, some said, or because Barkley had infuriated him by belittling his Christmas trees, or because some New Dealer—Morgenthau or Byrnes or Rosenman or Paul—was really in control of fiscal policy. But it became evident that Roosevelt had written most of the cutting phrases in the veto message—and this fact helps explain Roosevelt’s action. He had come home from a global mission to a squabbling capital. The barons on Capitol Hill in particular—George, McKellar, Rankin, and the rest—seemed to symbolize the parochialism, the selfishness, the greed, the pettiness that Roosevelt felt was undermining the war effort. He himself was less patient, less receptive to advice from congressional spokesman, a bit less sparing of feelings. So his vetoing of the tax and other major bills, and his allowing the soldiers’-vote bill to become law without his signature, dramatized the gap between White House and Congress; but it also would leave the record clear.

And always—for all the politicians—loomed the portent of the fall, the ultimate test by ballot. What would Roosevelt do? At the White House correspondents’ dinner, the President threw back his head and roared as Bob Hope gabbed away: “I’ve always voted for Roosevelt as President. My father always voted for Roosevelt as President….”

It was widely assumed in Washington that Roosevelt would run for a fourth term only if the war was still on by summer 1944. Many Americans thought the war would be over and won by that time, but the President himself had always been loath to predict an early victory. “We have got a long, long road to go,” he told visitors early in March 1944. “We are going to win the war—it is going to take an awfully long time.”

The President spoke at a time when the war in Italy—the only active Allied front in the West—was going badly. Inching up the long valleys north of Naples, Mark Clark’s Fifth Army and the British Eighth Army, with polyglot elements from other nations, had fought their way through the Germans’ winter line and had come up hard against the Gustav Line, anchored in jutting, snow-covered mountains. Here was a soldier’s purgatory—rough, brushy terrain cut by gullies and stream beds and flanked by rocky terraces, knife-edge cliffs, broken ridges, all of which favored the defenders. The sunny days of Calabria had given way to weeks of pelting rain and wet snow that turned fields into swamps and quagmires. The drenched, shivering soldiers crouched in foxholes or thigh-deep in swamplands were an ironic symbol. The kind of draining, positioned warfare that Churchill had abhorred in the plains of France was appearing again in the mountains of Italy. When Clark’s 36th Division tried to force the Rapido River, south of Cassino, footbridges were blown up by mines or gunfire even while being erected; rubber boats sank under small-arms fire, and the few men who got across were trapped in barbed wire, mines, and machine-gun and shell fire. The 36th took 1,600 casualties in three days—and was not across the Rapido.

Churchill was dismayed but unmoved by the deepening stalemate in Italy. He would not change the Italian strategy, but would adjust other strategy to it. OVERLORD, he professed, still had highest priority, but must everything be subordinated to the “tyranny” of the cross-channel attack? As he saw the problem, the campaign in Italy was the vital counterpart to the main operation in France. He was still critical of the “American clear-cut, logical, large-scale” style of thought. “In life people have first to be taught ‘Concentrate on essentials’…but it is only the first step. The second stage in war is a general harmony of war efforts by making everything fit together….”

Though still feverish from pneumonia, Churchill had thrown himself into a battle to resuscitate the campaign in Italy. The stagnation on that front was scandalous, he told his Chief of Staff. A ray of hope was that Eisenhower planned an end run—an amphibious flanking attack behind the Germans at Anzio, thirty-eight miles south of Rome, conjoined with a renewed attack on the Gustav Line. Churchill was elated by this plan for a “cat claw.” The rub was that fifty-six LST’s destined for Britain and ERLORD would have to be held in the Mediterranean for the operation. Churchill sent a long, pleading letter to Roosevelt. The Italian battle could not be allowed to stagnate and fester, he insisted. A vast half-finished job could not be given up. The cat claw should decide the Battle of Rome and perhaps even destroy much of Kesselring’s army. If this opportunity was lost, the Mediterranean campaign of 1944 would be ruined.

Once again Roosevelt confronted a Churchillian squeeze play in the Mediterranean; once again his Chiefs of Staff and planners worried about the suction pump; once again the President gave in. He did remind the Prime Minister that under the Teheran pledges he could not agree without Stalin’s approval to any use of forces or equipment elsewhere that might delay or hazard the success of OVERLORD or ANVIL. “I thank God for this decision,” Churchill wired back, “which engages us once again in wholehearted unity upon a great enterprise.”

The cat claw struck Anzio on January 22. At first things went well. Undetected by the Germans, American and British assault troops met little resistance and quickly moved several miles inland. Unloading proceeded briskly. At this moment Kesselring’s reserves were committed in the battle against the major Allied attack to the south, and for a few intoxicating hours a lunge through to Rome seemed possible. Then came Hitler’s order of the day that the Führer expected the “bitterest struggle for every yard” for the sake of political consequences—the defense of Rome. The Anzio “abscess” must be liquidated. Ordering his Gustav Line troops on the defensive, Kesselring skillfully deployed his crack regiments into the Anzio perimeter. German divisions started moving down the boot of Italy. Fearing encirclement if they dashed toward Rome, the invaders fortified their beachhead positions and dug in. The attackers thus became the defenders. In the south the Allies stalled again below the formidable heights of Cassino. Roosevelt told reporters the situation was very tense.

Churchill was appalled at the failure to exploit Anzio. The wildcat hurled onto the shore, he complained later, had become a stranded whale. At least the whale was there to stay; heavy Nazi counterattacks came dangerously close to overrunning the beachhead, but the defenders hung on. It was clear that deadlock once again would grip the Italian front, that more men and supply would be needed, that the suction pump would speed up again. Once again tactics were colliding with strategy. It had been evident for some time that OVERLORD must be postponed until about the end of May. Now the British, who had never been very enthusiastic about ANVIL, were insisting that the planned invasion of southern France be scrapped or put off so that the full Mediterranean thrust would remain concentrated in Italy. German strength would be contained and bled below the Alps.

Roosevelt met with his Chiefs of Staff to consider this major proposal for altering the attack against Fortress Europe. The JCS saw the request as the latest in a long series of British efforts to favor the Mediterranean—efforts that seemed all the more curious now that the soft underbelly had turned out to be so hard. The President was mainly concerned with the political implications. He feared Soviet reaction to a cancellation of ANVIL; he did not want even to raise the matter at this point, when the usual rumors were flying around that Moscow (or Washington, or London) was seeking a separate peace with Berlin. Certainly ANVIL could not be scrapped without consulting Moscow first. The only immediate solution to the problem was to postpone a solution. In London, Eisenhower, ever the adjuster, worked out a formula that favored a further build-up in Italy but kept ANVIL alive.

The President confronted an even more crucial matter of strategy. During the long months of the early Italian campaign doubts had been rising among American military planners, and even more among British, as to the effectiveness of unconditional surrender. American army men at first accepted the presidential declaration without serious question, since it provided a definite, clear-cut goal of defeating the enemy decisively without getting into complex political and psychological problems. By early 1944 it became clear that Nazi propagandists were using the declaration as proof that the Allies were bent on exterminating the German nation and enslaving the German people. Intelligence officers in both London and Washington were becoming more and more doubtful about the doctrine, especially in view of the need to undermine Nazi resistance to the invasion of France. Late in March 1944 the Joint Chiefs of Staff asked the President to retreat from his uncompromising stand and to make clear now that the Allied intention was not to destroy the German people or nation but, rather, the German capacity for military conquest.

The Commander in Chief was adamant. With one eye on possible Soviet reaction to weakening on unconditional surrender, he told his chiefs:

“…A somewhat long study and personal experience in and out of Germany leads me to believe that German Philosophy cannot be changed by decree, law or military order. The change in German Philosophy must be evolutionary and may take two generations.” He was opposed to reconstructing a German state that would undertake peace moves. This might bring a period of quiet, but then a third world war.

“Please note that I am not willing at this time to say that we do not intend to destroy the German nation. As long as the word ‘Reich’ exists in Germany as expressing a nationhood, it will forever be associated with the present form of nationhood. If we admit that, we must seek to eliminate the very word ‘Reich’ and what it stands for today.”

Of course, the President said to Hull a few days later, there would have to be exceptions, “not to the surrender principle but to the application of it in specific cases.” This, he added, was a very different thing from changing the principle. “Germany understands only one kind of language,” he told Hull.

The President’s harsh attitude toward Germany was not unaffected by a growing burden on the world’s conscience. This was the agony of the Jews.

By January 1944 Morgenthau had been pressing Hull for months to move more vigorously on the complex actions needed to save thousands of Jews in their perilous refuges from Rumania to France. He had told Assistant Secretary of State Breckinridge Long to his face that the impression was all around that “you, particularly, are anti-semitic”; Long had denied it. At the turn of the year there was a flurry of activity in the State Department, but when Morgenthau visited Hull on January 11, 1944, he found the old man depressed and perplexed by the refugee situation. Morgenthau asked Randolph Paul to report on the urgency of the situation.

“Report to the Secretary on the Acquiescence of this Government in the Murder of the Jews,” Paul entitled his blunt indictment. It began: “One of the greatest crimes in history, the slaughter of the Jewish people in Europe, is continuing unabated.” He went on to charge that State Department officials had not only failed to use governmental machinery to rescue Jews from Hitler but also had used that machinery to prevent the rescue of Jews, had hindered private efforts, and had willfully covered up their “guilt.”

Morgenthau soon confronted the President with his own version of this report, which he had shortened but not tempered. Paul and John Pehle, the young head of Foreign Funds Control, accompanied their chief to the White House. Roosevelt, Morgenthau later told his staff, “seemed disinclined to believe that Long wanted to stop effective action from being taken, but said that Long had been somewhat soured on the problem when Rabbi Wise got Long to approve a long list of people being brought into this country many of whom turned out to be bad people….” But Morgenthau’s anguish and Pehle’s specific data impressed the President. The Secretary had brought along the draft of an executive order creating a War Refugee Board to take operations away from the State Department. Roosevelt approved the idea and asked Morgenthau to discuss it with Undersecretary of State Stettinius. Morgenthau did that very afternoon, and Stettinius approved.

Roosevelt acted within the week. He announced the establishment of the War Refugee Board, with Pehle as Acting Executive Director. “It is the policy of this Government,” the executive order began, “to take all measures within its power to rescue the victims of enemy oppression who are in imminent danger of death and otherwise to afford such victims all possible relief and assistance consistent with the successful prosecution of the war.” Composed of the Secretaries of State, Treasury, and War, and armed with funds and both legal and moral authority, the new board went right to work. It was fearfully late—in many cases too late. But at last the administration was putting some drive and persistence into the vast rescue operation.

“YOUR MOVE, TOJO”

December 14,1943, © Low, reprinted by permission of The Manchester Guardian

Within two months, indeed, Morgenthau could come to the White House with a hopeful progress report. His chief was keenly interested, but even while Morgenthau was talking about refugees, the President was thinking about the implications for Palestine. He was calculating how he could induce the British to promise publicly that if the Refugee Board actually brought Jews out of Europe, London would let them go to Palestine. “You know,” the President said to Morgenthau, “the Arabs don’t like this thing.” Neither did Morgenthau—he was not a Zionist—but he, Stimson, and Pehle persuaded the President to support emergency refugee shelters in the United States. Fearing opposition on the Hill, the President took steps to bring 1,000 refugees from Italy to an emergency shelter in Oswego, New York—and then simply announced his plan to Congress. The suction pump was still working in the Pacific, too. At the close of the second Cairo Conference Roosevelt and Churchill had initialed a revised plan for defeating Japan. The pivot of strategy would no longer be a mere holding operation around the vast Japanese perimeter, or a counteroffensive based on hopping from one island to the next, or even the long-planned major thrust through Burma and China. The planners now proposed a line of attack as bold and direct as OVERLORD itself—a massive amphibious operation sweeping across the western Pacific, outflanking and isolating big enemy bases, blockading the home islands by sea and air, and then closing in for the final assault. The Pacific advance would be two-pronged. The advance along the New Guinea-Netherlands East Indies-Philippine axis would proceed concurrently with operations to capture the Mandated Islands. The two series of operations would be mutually supported.

Roosevelt was delighted with the plan. Capitalizing on the enormous build-up in supply and troops, it would permit crushing blows against Japan even while the war in Europe continued, and it would meet popular demands for a greater effort in the Pacific. After talking with Eisenhower and Halsey in Washington shortly after the new year began, the President told reporters that the greatest possible pressure would be brought to bear on the European and Pacific theaters simultaneously.

Glittering naval and amphibious feats had made this plan seem feasible. In November 1943 Marines and soldiers under Admiral Spruance had counterattacked on Makin and Tarawa in the Gilbert Islands, now part of the Japanese outer defenses. War had rarely found a lovelier setting—curving ribbons of golden beaches and lowlands and coral reefs embracing placid lagoons, all brushed by warm winds from the encircling Pacific. But embedded under the sand and the rustling palm trees were hundreds of pillboxes built of concrete five feet thick, with roofs of iron rails laid on coconut logs, protected by outer walls of sand and coral ten feet thick. American planes and warships engulfed these tiny islands in flame; amphibious tractors ground toward shore with their machine guns firing; heavily laden Marines and soldiers stormed over the lacerating reefs and closed in on the enemy, only to see the strong points come alive and respond with withering, close-up fire. The only way to win was to advance foot by foot, enfilading pillboxes, pouring automatic fire into gun slits, lofting grenades, poling in TNT attached to long iron pipes, burning Japanese alive in their dugouts or flushing them out and gunning them down. On tiny Tarawa the Marines lost 1,000 dead and killed 3,000 of the enemy.

The Gilberts proved that American troops could capture powerful island bastions once they closed in on them—and that the Japanese Navy could not keep them away. The crucial step was the seizure of control of the central Pacific by Nimitz’s fast-growing Navy. By 1944 his carriers and cruisers were ranging almost at will in the vast area. Despite occasional disasters—the carrier Liscombe Bay was torpedoed with the loss of over two-thirds of her company—the fleet was big enough to feint widely dispersed attacks and then isolate a target and overwhelm it. In February Nimitz’s men seized key islands in the Kwajalein atoll. The Japanese made little effort to counter the heavy onslaught; Imperial Headquarters had decided to let the outlying garrisons conduct delaying actions while the main defense fell back to the perimeter of Timor—western New Guinea—Truk—Marianas. Kwajalein, key point in the atoll, was seized in several days of furious fighting the first week of February; Eniwetok atoll, only 1,000 miles from the Marianas, fell later in the month. The Eniwetok attack had been planned for mid-1944; Spruance had the mobility and the power to accelerate.

The President could be proud of his Navy, Forrestal reported to him during the Kwajalein fighting. The difference in the Navy’s teamwork now over 1942 was as of night and day. “It had the most meticulous plan…a substantial result at an astonishingly small cost….”

To the south and west Halsey and MacArthur were now accelerating their long climb up the twin ladders of New Guinea and the Solomons. American and Australian troops spent most of late 1943 subduing Japanese forces in southeastern New Guinea; then MacArthur leaped four hundred miles to Hollandia on the northern coast, outflanking 50,000 Japanese in between. Next he hopped another three hundred miles to seize Biak Island. Halsey’s forces captured New Georgia during the summer of 1943, gained naval control of the whole northern Solomons area, and he and MacArthur combined forces to seize the Admiralty Islands, bypassing the enemy bastion of Rabaul. Both ladders pointed directly at the Philippines.

In his map room the President studied the great blue charts of the Pacific showing the latest advances and dispositions. He knew that the British Chiefs of Staff were so impressed by his Navy’s Pacific operations that they were yearning for British fleet units to help out in the central Pacific and then take their place on MacArthur’s left flank. Though no less impressed, Churchill was urging his chiefs to put the main weight of the British effort against Japan not in the Pacific, and not even in Burma and China, but in Sumatra and Malaya, with an eye to the recapture of Singapore. In Asia, too, Churchill wanted an underbelly strategy, with postwar aspects in view. So strongly did he feel, indeed, that he denied even understanding the Pacific plan adopted at Cairo—though he did not deny having initialed it—and this difference between Churchill and his chiefs became so acute during the winter of 1944 that they hinted they might resign.

Roosevelt made his own position clear to Churchill. “My Chiefs of Staff are agreed that the primary intermediate objective of our advance across the Pacific lies in the Formosa—China coast—Luzon area. The success of recent operations in the Gilberts and Marshall indicates that we can accelerate our movements westward.…I have always advocated the development of China as a base for the support of our Pacific advances.” Every effort, he went on, must be made to increase the flow of supplies into China, and this could be done only by increasing the air tonnage or by opening a road through Burma. He urged Churchill to give Mountbatten his energetic encouragement in the campaign in Upper Burma.

Roosevelt’s letter reflected a continued lowering of earlier American hopes that southern China could become the main base for the final assault on the home islands. As both Stilwell’s forces and the British took the offensive in northern Burma during the late winter of 1944, Roosevelt hoped to boost the airlift of supplies over the “Hump” and to push roads and pipelines into China. In personal letters to Roosevelt and Hopkins, Chennault was pleading for more supplies and promising that with them his Fourteenth United States Air Force could sink 200,000 tons of Japanese shipping a month along China’s coast.

“To one with your war experience and special mastery of naval strategy,” Chennault wrote to Roosevelt, “I need hardly point out that the Japanese position in South-east Asia and the South-west Pacific must soon fall, if Japan has not the shipping and air power to support them.” He contended that air attacks on shipping in the months ahead would be far more conclusive than strategic bombing of the homeland.

Roosevelt wrote a warm—and noncommittal—answer. “You are the Doctor,” he ended, “and I approve your treatment. Nevertheless, as a matter perhaps of sentimentality, I have had a hope that we could get at least one bombing expedition against Tokyo before the second anniversary of Doolittle’s flight. I really believe that the morale effect would help!”

The President shared the high hopes of the time for American air power on both continents. From Britain hundreds of B-17’s and B-24’s had been striking German targets throughout 1943, focusing on high-priority objectives such as the ball-bearing plants at Schweinfurt and aircraft factories in Regensburg and Bremen. Some of the bombing had been brilliantly effective; other forays had been tragically expensive—as in the loss of sixty out of 228 bombers attacking Schweinfurt in mid-October—and often the Air Force estimates of damage inflicted and enemy planes shot down were grossly exaggerated. This was not merely a public-relations effort; unwittingly inflated reports and hopes reached the Air Force command and the President himself.

By January 1944, indeed, hard-nosed British Intelligence officers were indicating that Goering’s fighter force was still increasing. Factories were smashed, workers killed, but the vital machine tools were dragged back into place and made to run again. The Germans were now dispersing their key war plants. This situation boded ill both for deep penetration bombing and for OVERLORD, which would require almost absolute command of the air. “My personal message to you,” Arnold wrote to the commanders of the Eighth and Fifteenth Air Forces on New Year’s Day, “this is a MUST—is to, ‘Destroy the Enemy Air Force wherever you find them, in the air, on the ground and in the factories.’ ” The arrival of long-range fighters in early 1944 gave the bombers vitally needed protection over their targets. Late in February the skies cleared over Germany, and 3,300 bombers from the Eighth Air Force and five hundred from the Fifteenth dropped almost 10,000 tons of bombs, with the loss of 226 bombers. Early in March the Eighth bombed Berlin heavily, for the first time. But in the heart of Europe the Luftwaffe was still putting up fierce resistance.

Berlin, Anzio, Kwajalein, Burma—these were but pinpricks compared with the mighty thrusts in the east. In January 1944 the Russians broke the Leningrad blockade. In February and March Soviet troops outflanked several Nazi divisions in the Korsun salient on the Dnieper and in a “mud offensive” pushed toward Rumania. In April they liberated Odessa. The Russians now were killing and capturing Germans by the tens of thousands; their own losses were frightful as always. Stalin, who had politely seized every opportunity to congratulate Roosevelt on Allied successes during 1943, was silent during the early months of 1944. He, too, was waiting for OVERLORD.