THERE IS SOMETHING BOTH strange and sublime about a great democracy conducting free elections in the midst of total war. Strange because at the very time a people is most unified over its goals and most determined to achieve them it divides into contending parties, mobilizes behind opposing doctrines, and pits gladiator against gladiator in the electoral arena. Sublime because in the act of holding an election a people reaffirms its faith in the democratic process despite all the compelling reasons to suspend it. Even Britain, a seedbed of democratic practice, postponed general elections during World War II, as in the first war.

Some doubted that the nation—or at least Roosevelt—could go through with a wartime presidential election. At a press conference early in February a reporter mentioned rumors in the anti-Roosevelt press that the election would be called off. Roosevelt pounced on him.

“How?”

“Well, I don’t know. That is what I want you to tell me.”

“Well, you see,” Roosevelt said, “you have come to the wrong place, because—gosh—all these people around town haven’t read the Constitution. Unfortunately, I have.”

An Englishman observing the American scene early in 1944 marveled at the differences in Roosevelt’s and Churchill’s situations. The Prime Minister had the backing of a united nation, S. K. Ratcliffe noted, while the President moved in an atmosphere of conflict—of political bitterness, industrial discord, racial tension, press opposition, Democratic party defections—and “of an enmity against him so intense and persistent that for a parallel in Britain we would have to go far back.”

The White House mail reflected the bitterness. “In conclusion candidate Roosevelt,” wrote a Californian, “you are a politician I would not trust; for you use men to promote your desire for power and more power and when their usefulness is at an end, they are cast aside, as you double-crossed Al Smith at the 1932 Chicago Convention in your deal with Hearst (whom you now revile), McAdoo and Garner. Both you and your wife, Eleanor Roosevelt, have done more during your incumbency to promote and stir up class, racial hatreds….May God pardon you.” From a New Jerseyite: “The people of the U.S. of America do not like any longer boss rule, nor dictated by a machine….” Of the several hundred persons who wrote in against a fourth term some had specific complaints, some general, but many simply hated Roosevelt.

Many still loved him, or needed him. “Please President Roosevelt don’t let us down now in this world of sorrow and trouble. If we ever needed you is now. I believe within my heart God put you here in this world to be our Guiding Star….” Some letters came from organized groups; 6,100 steelworkers signed a petition, “We know that you are weary—yet we cannot afford to permit you to step down….” Few letters dealt with issues, programs, specific goals; here again a gap yawned between great cloudy war aims and peoples’ specific needs.

An undercurrent of worry about Roosevelt’s health ran through many letters from both friend and foe. From San Diego: “I don’t believe in working a good horse to death—so don’t try to carry the whole world on your shoulders.” From a woman in Brooklyn: “…You did many fine and wonderful things for this country, no doubt….Resign, retire to your New York State home rest—and in time enjoy the fruits of your endeavours.” One or two advised him to step down and head the peace delegation.

Messages came from Berlin, too. Election year had hardly started when Douglas Chandler, a former Hearst newspaperman who broadcast regularly from Germany under the name Paul Revere, called on his fellow Americans to repudiate the traitor, the charlatan, the weakling in the White House. America, he said, was on the brink of a reign of terror—and, even worse, inflation. “Get that man out of the house that was once white!” Adolf Hitler had cast his ballot early.

It might seem that, in theory at least, the most ticklish role in wartime politics would be the opposition’s. To conduct a campaign at home against an administration conducting a campaign against the enemy overseas, to agitate and divide the country, to attack the Commander in Chief—politicians might be expected to recoil from such unpopular ventures. But not the pragmatic office seekers of America. By the inexorable calendar of American politics it was election year and hence it was time to smite the party in power, war or no war. By early 1944 the GOP was seething with hope and stratagems, and several men were seeking the Republican nomination.

The most active of these was Wendell Willkie. The 1940 nominee had refused to fade away after his defeat. His global travels, his writings, his calls for strong postwar world organization, his eloquent defense of Negroes and other minority groups, his double-barreled attacks on congressional Republicans and on the Roosevelt administration kept him in the public eye. But by 1944 he was a man without a party. He was still anathema to the congressional Republicans; he had never built a strong grass-roots organization within presidential Republican ranks, and what organized support he had mustered had partly melted away during the war.

Willkie was still a commanding figure, with his big burly frame, shaggy hair, muscular phrases, and blunt assaults on his enemies. But a note of desperate frustration was creeping into his speeches. He lambasted the reactionaries, bigots, and stand-patters in his own party even more bitterly than the racists and reactionaries in the Democratic. Introduced by an industrialist as “America’s leading ingrate” to those who had helped him in 1940, he burst out, “I don’t know whether you are going to support me or not and I don’t give a damn. You’re a bunch of political liabilities anyway.” He was forever telling Republicans that they could take him or leave him—and many left him. He said all the right things about the Democratic regime—one-man rule, confused administration, self-perpetuation in power—but his criticisms of presidential Democrats seemed to lack the bite and crunch of his attacks on congressional Republicans.

His only hope in 1944, in contrast to his last-minute blitz four years before, was to demonstrate his popularity in a string of primaries. He won a small victory in New Hampshire and then plunged into Wisconsin. He calculated that if he could carry this Midwestern state, with its big German-American population and isolationist tradition, he would have met the crucial test. Day after day before big crowds he lashed his foes—the Chicago Tribune, New Deal regimentation, trimmers and poll-takers in his own party—in an exhausting campaign through the cities and towns of Wisconsin. It was like punching air—no other candidate was there to face him. But his lieutenants hoped to win a clear-cut majority of delegates, perhaps even all of them.

The results were clear-cut enough. He won not a single delegate. His leading delegate candidate ran a poor fourth to the top Dewey, MacArthur, and Harold Stassen men. Appalled and played out, Willkie told a crowd that he was quitting the race. He had hoped, he told his startled listeners, that the Middle West, the matrix of so many moral causes, would help produce new leadership. “Perhaps the conscience of America is dulled. Perhaps the people are not willing to bear the sacrifices, and I feel a sense of sickening because I know how much my party could do to make it worthy of its tradition….”

Roosevelt read the results with mixed feelings. Not only did he admire his old adversary in certain ways, but also he had reason to feel uneasy about the two candidates left in the running.

The more notable of these was Douglas MacArthur, Roosevelt’s old acquaintance, onetime Chief of Staff, and present subordinate. The President no longer considered MacArthur, along with Huey Long, one of the two most dangerous men in the country, as he had ten years before, but he could not ignore the General. MacArthur was still the darling of the congressional Republicans and the Hearst-McCormick-Patterson press, with their Pacific First strategy, neoisolationist tendencies, and anti-New Deal feelings. While publicly aloof, the General privately was making known his willingness to be drafted. After Vandenberg had shown some interest in MacArthur, the General wrote him an effusive letter intimating that there was much he would like to tell Vandenberg “which circumstances prevent” and asking for the Senator’s “wise mentorship.” Encouraged and spurred by the General’s missionaries to Washington, a small group of conservative Republicans—Vandenberg, publisher Frank Gannett, General Robert E. Wood, of Chicago, former head of America First, among others—quietly fostered MacArthur sentiment. The General made clear that he would accept the nomination only if drafted; otherwise he stayed out of the struggle and communicated through intermediaries.

April 10, 1944, C. K. Berryman, courtesy of the Washington (D.C.) Star

The politicos in the White House watched the boomlet closely. It was clear that MacArthur, if nominated, would campaign for Pacific First; it was possible that he would charge Roosevelt with inadequately preparing the nation for war, with deserting the Philippines and starving the Southwest Pacific theater. The General had repeatedly put himself on record with the Pentagon and the White House about his grievances; his documented appeals would make good campaign material in the fall. But also on record in the White House, in the secret files of the President’s naval aide, was the transcript of a discussion between MacArthur and Navy chiefs the day before Pearl Harbor. During this discussion the General had said that he was sure he could defend the archipelago as a whole and that his greatest security was the “inability of our enemy to launch his air attack on our islands.” That, too, would make good campaign material in the fall.

For the MacArthur backers everything depended on retaining control of their boom for the General, keeping his name out of the presidential primaries, and timing developments so that he would be summoned to higher duty by the Republican convention. But too many Republicans, desperate to find a candidate who could match Roosevelt’s glamour and appeal, crowded onto the small bandwagon. One of these was a Nebraska Congressman who rashly published an exchange of letters with MacArthur in which the Congressman had intemperately attacked the New Deal, and the General had expressed complete agreement with his views and had gone on to refer darkly to the “sinister drama of our present chaos and confusion.” The publicity and the ensuing furore pricked the MacArthur bubble; he announced that he did not “covet” the nomination and would not accept it because no high officer at the front should be considered for President.

And then there was one….Thomas E. Dewey had not had to lift a hand while his rivals ran into pitfalls and booby traps. Grandson of a founder of the Republican party in 1854, son of a Republican editor and postmaster in a small Michigan town, he had not only lived a Horatio Alger boyhood, but also at thirteen had nine other boys as his agents peddling the Saturday Evening Post and Ladies’ Home Journal. After graduating from the University of Michigan and from Columbia Law School, he joined a New York law firm in the mid-1920’s, practiced obscurely there for six years, then as a mob prosecutor and racket buster won almost instant fame by putting the likes of Legs Diamond and Lucky Luciano behind bars. Dewey was always in a hurry. Elected District Attorney for New York County on the La Guardia ticket in 1937, the next year he took on the redoubtable Herbert Lehman in a race for governor. He lost so narrowly that he was emboldened to seek the Republican presidential nomination in 1940. He led strongly on the early ballots at the Philadelphia convention, only to fall before the Willkie boom. Two years later, with Lehman out of the way, he captured the governorship in a smooth operation.

At forty-two Dewey was a seasoned young professional, with his share of wins and losses. Already he had acquired a reputation for being stiff, humorless, overbearing. With his waxworks mustache and features, his medium height, and his deep baritone he lent himself to cruel remarks: he was the bridegroom on the wedding cake, the only man who could strut sitting down, a man you really had to know to dislike, the Boy Orator of the Platitude. But his adversaries had learned not to underestimate him. He was the clear-cut choice of the Republican rank and file as well as the presidential-party leadership during the early months of 1944. He was running an expert noncampaign. He exuded energy, efficiency, purpose.

The New York Governor had done such a professional job in rounding up delegates, in fact, that he won easily on the first ballot in Chicago. It was a dull convention, enlivened only by Dewey’s choice of John W. Bricker, the popular, wavy-haired Governor of Ohio, as his running mate. Bricker was no savant—his mind had been compared to stellar space, a huge void filled with a few wandering clichés—but all agreed that the two men made a strong ticket. And when Dewey, in his acceptance speech, lambasted the Democrats for having grown old and tired and stubborn and quarrelsome in office, he made clear the grounds on which he would carry the attack to the Roosevelt administration.

May 18,1944, C. K. Berryman, courtesy of the Washington (D.C.) Star

There was little suspense about the Democratic nominee. The President told friends that he wanted to return to Hyde Park “just as soon as the Lord will let me,” but by early 1944 there was no doubt in the White House, and little outside, that he would run again, certainly if the war was not yet won. After sparring with reporters for some months, Roosevelt in July handed them copies of a letter to Robert E. Hannegan, now Chairman of the Democratic National Committee, stating that he did not want to continue in the White House after twelve years but that if the convention nominated him and if the people—“the Commander in Chief of us all”—ordered him, as a “good soldier” he would serve.

The big question was his running mate. It was clear that whether the President completed another term or not, the next Vice President would be in a commanding position in 1948. Who was Roosevelt’s choice? The President never—not even in 1940—pursued a more Byzantine course than in his handling of this question.

Relations within the top echelons of the Democratic party in early 1944 were reminiscent of the old description of the Massachusetts Democracy as the systematic organization of hatred. Congressional Democrats were threatening to bolt the party, or at least withhold Southern electoral-college votes from the President. Texas and Virginia Democrats were in open revolt. CIO unions and liberal journals, along with a number of people close to Roosevelt, including Eleanor Roosevelt, backed Wallace; most of them opposed Byrnes. A covey of Democratic politicians—Hannegan; Edwin Pauley, Treasurer of the Democratic National Committee; Postmaster General Frank Walker; George E. Allen, Secretary of the National Committee; Boss Ed Flynn of the Bronx—opposed Wallace; so did Pa Watson and Steve Early. Friends of Pauley boasted that the California oil man journeyed from city to city urging local leaders to send reports to the White House about Wallace’s unpopularity, and that Pauley had made a deal with Watson that Pa would clear the way into the oval office for anti-Wallace Democrats.

Roosevelt was pursuing his own line. While not discouraging Wallace, he subtly and openly encouraged others. His handling of vice-presidential ambitions in 1944 was much like his crafty, brilliant management of presidential rivalries four years before. At that time he had not only encouraged existing candidates to contend with one another but also had adroitly enlarged the field so that potential opposition would be fragmented and thus more manageable. So in 1944 he tempted Byrnes, who had earlier decided he would not try for the job; Hull, who flatly declined; and, by no indication he was out of favor, Vice President Wallace. Word leaked out at various times that the President looked with favor on Barkley, Rayburn, Truman, Winant, Justice Douglas, McNutt, Henry Kaiser, and several others. Wallace was leading in the polls; the President did not help his chances when in May he dispatched him on a mission to Asia, for Roosevelt sometimes sent abroad people he intended to let go.

May 16, 1944, C. K. Berryman, courtesy of the Washington (D.C.) Star

By early July, with the convention scheduled for Chicago at the end of the month, Roosevelt could not put the matter off much longer. The smoke-filled room of the 1944 Democratic convention took place two weeks early, in the President’s sweltering second-floor study, where he met on the evening of July 11 with Hannegan, Walker, Flynn, and others to canvass the field. One by one the names of front runners were lobbed up and smashed down. Byrnes, a Southerner and ex-Catholic, would alienate Negroes, Catholics, and liberals, according to the conventional wisdom of the canvassers. Barkley was too old. Wallace was so clearly anathema to the group that he was hardly discussed. Roosevelt trotted out Douglas’s name—he was young, dynamic, he said, and, besides, played a good game of poker—but the others were cool. The talk turned to Truman. Roosevelt liked him for his personal loyalty and legislative support even while running an effective war investigation committee. The others approved his strong partisan background and instincts. He was from the Midwest, from a politically doubtful border state. The President did seem worried about Truman’s age and sent someone out to check it, but he wandered away from the subject and it never came up again.

Everybody seemed to want Truman, Roosevelt said with an air of finality. The meeting broke up, but Hannegan, worried that the President might change his mind, got him to pencil a one-line note that Truman was the right man.

How to inform Wallace and Byrnes that Truman had the nod? As usual Roosevelt left this distasteful job to his subordinates. Rosenman and Ickes got hold of Wallace, who had just returned from China. The Vice President was calmly adamant. People were starving to death in Asia by the hundreds of thousands, he told the emissaries; he would talk politics only to the President. At the White House he showed Roosevelt his list of delegate support, his high standing in the polls. Roosevelt seemed to be surprised and impressed. He even discussed possible tactics. And he promised the Vice President a letter of personal endorsement. As he left, the President reached up and put his arm around him. “I hope it’s the same team again, Henry.”

Byrnes was equally obdurate. When Hannegan and Walker came with the bad news, he insisted on phoning the President at Hyde Park, and he took down the President’s answer in shorthand. Was the President allowing people to speak for him?

Roosevelt: “I am not favoring anybody. I told them so. No, I am not favoring anyone.”

Why were Hannegan and Walker quoting him as favoring Truman or Douglas?

“Jimmy, that is all wrong. That is not what I told them. It is what they told me.” He had not expressed preference for anyone.

Again Byrnes pressed him on the matter.

Roosevelt: “We have to be damned careful about words. They asked if I would object to Truman and Douglas and I said no. That is different from using the word ‘prefer.’…” He ended by virtually urging Byrnes to run.

By the time the Democrats convened in Chicago they were in a delicious state of confusion. While vice-presidential fever was sweeping the leadership, the delegates milled about in more than the usual state of ignorance. Byrnes had lined up Truman’s support so solidly behind his own candidacy that the Missourian was not fulfilling his assigned role as number-one dark horse. Hannegan and his friends were trying to sidetrack Wallace without putting in Byrnes. Hillman was working hard for Wallace but keeping a line of retreat open to Truman. Ickes was working for either Douglas or Truman—some said just for Ickes. Before the convention started, the President had stopped his train in Chicago on his way to San Diego and complicated things further by reissuing his penciled chit to Hannegan to read as an endorsement of Truman and Douglas—either to show he was not trying to run the convention or just to keep things confused.

Wallace’s big weapon was a letter Roosevelt had written about him to the convention chairman: “I like him and I respect him and he is my personal friend. For these reasons I personally would vote for his renomination if I were a delegate to the convention.” But the letter ended by leaving the matter up to the convention. To some it looked like the kiss of death; others wondered if it might put the Vice President over the top. It might have if Hannegan and his cohorts had not finally broken Truman loose from his pledge to Byrnes. Roosevelt, by now in San Diego, had to do this job, too; after Hannegan had got Truman together with Walker, Flynn, and Chicago boss Edward J. Kelly in a room at the famous Blackstone Hotel and put a call through to the President, Roosevelt demanded: “Have you got that fellow lined up yet?”

The answer was no. Truman still could not believe that the President was supporting him over Byrnes and Wallace.

“Well, tell the Senator,” the President said, “that if he wants to break up the Democratic party by staying out, he can; but he knows as well as I what that might mean at this dangerous time in the world….” Convinced at last, Truman asked Byrnes to release him. Wallace led the pack strongly on the first ballot, with Truman, Bankhead, and Barkley following, but the city bosses and the Southern Bourbons converged on the next ballot to put Truman over. Earlier Roosevelt had been routinely renominated; Harry Byrd received eighty-nine votes, virtually all from Southerners, and Farley one. The President had asked for and got a short, mildly New Deal, internationalist platform. He gave his acceptance speech from San Diego over the radio to the delegates sitting in the Chicago Stadium.

“I have already indicated to you why I accept the nomination that you have offered me—in spite of my desire to retire to the quiet of private life….

“I shall not campaign, in the usual sense, for the office. In these days of tragic sorrow, I do not consider it fitting. And besides, in these days of global warfare, I shall not be able to find the time. I shall, however, feel free to report to the people the facts about matters of concern to them and especially to correct any misrepresentations….

“What is the job before us in 1944? First, to win the war—to win the war fast, to win it overpoweringly. Second, to form worldwide international organizations, and to arrange to use the armed forces of the sovereign Nations of the world to make another war impossible within the foreseeable future. And third, to build an economy for our returning veterans and for all Americans—which will provide employment and provide decent standards of living.”

The President rarely closed an address by quoting a famous speech, but the peroration of Lincoln’s Second Inaugural seemed apt for the occasion:

“With firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the Nation’s wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan—to do all which may achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace among ourselves, and with all Nations.”

After allowing a decent interval for Democratic convention oratory Dewey resumed his campaign against the tired administration and one-man government. The best way to counter this line of attack, Roosevelt knew, was through action rather than words. His long trip to California, Hawaii, and Alaska was to be testament to a Commander in Chief radiating energy and confidence. But Dewey had a point. So much did depend on that one man. And as the domestic battlelines were forming there were ominous signs that the pressure was too heavy, the body too fragile.

In his railway car in San Diego just before he was to leave to watch the landing exercise, the President was chatting with his son James. Suddenly his face turned white and agonized. “Jimmy, I don’t know if I can make it—I have horrible pains.” For minutes his father’s eyes were closed, his face drawn, his torso convulsed by waves of pain. He refused to let Jimmy cancel his appearance. Then he recovered and was able to leave for the exercise. However serious this episode may have been, it was not reported to Bruenn.

Rumors were spreading. A story circulated even in the White House that the President had had a secret operation at Hobcaw in May. In Hawaii, Roosevelt received word from Hopkins in Washington that an FBI agent in Honolulu had reported to J. Edgar Hoover that the Pacific trip had been canceled because of the President’s ill-health. He hoped the report was untrue, Hopkins wired, but if true that some other reason would be given. “The underground is working overtime here in regard to your health.” Leahy replied that the President had worked fourteen hours straight the day before and was never in better health, and that the FBI agent should be disciplined for making a false report.

The camera that had projected Roosevelt’s radiant face throughout the world could also be cruel. One widely used picture of Roosevelt making his acceptance speech showed a gaunt, shadowed face and a slack, open mouth; Rosenman lamented that Early was not there to prevent that kind of picture from going out, as Early had done in the past.

Perhaps the President missed the feeling of human contact in making his acceptance speech from San Diego; perhaps his mind went back to his dramatic flight to the Chicago convention in 1932 to pledge “a new deal for the American people”; or to the Philadelphia acceptance speech in 1936, when he proclaimed that “this generation of Americans has a rendevous with destiny.” Certainly he wanted a live audience for his first appearance back on the mainland after his Pacific trip. He asked Mike Reilly to make arrangements for a speech in the Seattle baseball stadium. Reilly, anxious about security, appealed to Rosenman and Hopkins, who cabled that the President should not be in the position of having crossed the country in one direction in secrecy and then making a speech to a civilian audience on the way back. Why not speak from the deck of his destroyer with its guns as background? The President liked the idea.

To thousands of Bremerton workers jamming the docks—and to a nationwide radio audience—the President gave a chatty travelogue about his Pacific journey. To his aides the talk seemed a near-disaster. The President spoke in the open, against the wind; on the curved deck his braces, which he had been wearing less and less during the war years, were ill-fitting and uncomfortable; his delivery was tepid and halting. Rosenman’s heart sank as he sat by the radio and heard the rambling speech.

What Rosenman did not know—and probably Roosevelt himself never knew—is that during the first part of this speech the President was suffering the first and only attack of angina pectoris he had ever had, or would have. Standing just behind him, even Bruenn could not tell what was happening. For about fifteen minutes the oppression gripped Roosevelt’s chest and radiated to both shoulders; then the severe pain slowly subsided. Roosevelt told Bruenn right after the talk that he had had some pain; within an hour a white blood count was taken and an electrocardiogram tracing made. No unusual abnormalities were found.

Once again tongues started wagging. Rosenman knew all about the chatter at Washington and New York cocktail parties, about the questions people were asking: Has the master lost his touch? Is he a setup for Dewey’s punches? Some of Roosevelt’s intimates worried less about this than about Roosevelt’s boredom with political detail. He had seemed curiously disengaged concerning the vice-presidential canvassing at the White House. At San Diego he told Jimmy that he didn’t give a damn whether the convention chose Douglas or Byrnes or Truman; the important thing was to get on with the war. The Bremerton speech—his first contact with the American people since his acceptance address over three weeks before—he prepared hastily on the destroyer without the help of speech writers. Still, he was not detached about the rumors of his bad health. When Reilly confessed to him that he had allowed reporters to glimpse the President at Hobcaw to counter their taunting claims that he was actually hospitalized in Boston or Chicago, Roosevelt’s lips tightened and his eyes glittered. “Mike, those newspapermen are a bunch of God-damned ghouls.”

The President’s most effective electioneering technique, at least early in the campaign, had always been that of maintaining his presidential posture, above the battle. While activists like Ickes chafed and fretted, while the Republican candidate sought to come to grips with his foe, Roosevelt continued just being President, offering as small a partisan flank as possible for the opposition to bombard.

Being President meant that he could propose and sign popular legislation. In early summer he approved the GI Bill of Rights, which revolutionized the whole approach to the returning soldier. The emphasis was less on a bonus or reward and more on education and individual achievement. Education or training at any level from primary grades to postgraduate would be allowed an ex-serviceman for one year plus the time served in the armed services, up to a total of four years. The bill also provided for a federal guarantee of half of the amount of loans made to veterans to buy or build homes, farms, and business properties; authorized substantial unemployment allowances for jobless veterans; set up machinery to help returning veterans find jobs; and authorized the building of more hospitals. The GI Bill was the capstone of a structure of veterans’ benefits fashioned during the war: dependency allowances; mustering-out pay; broad medical care; death and disability pensions; war-risk life insurance; re-employment rights for returning ex-servicemen, and more.

“It gives emphatic notice to the men and women in the armed forces,” Roosevelt said in signing the bill, “that the American people do not intend to let them down.” It was not the kind of action or statement that presented an inviting target to the Republicans.

Being President meant laying exciting plans for the postwar future. Roosevelt proposed perhaps the most dramatic of these at summer’s end when he called for a Missouri River development plan that would be based on the TVA concept that a big river basin contains one river and one set of interrelated problems and opportunities. In spurning a piecemeal legislative program for the basin, the President defied the innumerable groups that clustered around the existing power, recreation, irrigation, transportation, agricultural, and commercial interests in the basin. He called, too, for a study of the Arkansas and Columbia River basins, also with the TVA model in view.

Being President meant upholding the law. In the heat of August the Philadelphia transit system, serving almost a million war workers, came to a halt when motormen quit work because eight black employees had been upgraded to motormen. Strike leaders protested that motormen sat on the same wooden benches between runs and “the colored people have bedbugs.” As thousands trudged to work in ninety-seven-degree heat and tension rose in the black enclaves, the President intervened from far out in the Pacific. Under his proclamation the Army took control of the transit system, ordered strikers to return, vainly waited two days for compliance—then moved 8,000 armed soldiers into the city, arrested the strike leaders, warned younger strikers that their draft deferments would be canceled, put two soldier guards behind each complying motorman, got the trolleys rolling again—and protected the Negroes’ rights to their jobs.

During these summer months Roosevelt was conducting a curious venture in grand political strategy at home—curious because he ordinarily shunned broad political planning, curious, too, because years later it was still unclear whether he was seriously engaged in fundamental political reform or simply attempting an election ploy.

Certainly the political state of affairs cried out for a major confrontation. By 1944 Roosevelt and Willkie were both badgered and frustrated by the conservative wings of their parties; the presidential Democrats and the presidential Republicans were each under sharp challenge by the opposing congressional party. Roosevelt had been defeated on major legislation, such as taxes, and several of the Southern Democracies were openly defying him. Willkie was so impotent after Wisconsin that he was not even seated as a delegate in the Republican convention, much less invited to speak to the conclave or to testify before the platform committee. He felt more bitter than Roosevelt about his own congressional-party foes. He condemned the postwar international-security plank of the Republican party platform—actually a restatement of the Mackinac formula—as a betrayal of the youth of America. It was only natural under the four-party pattern of American politics during this period that Willkie seemed to have more friends at the Democratic convention than at the Republican and that there was even some scattered interest in making him Roosevelt’s running mate.

One day toward the end of June the President called Rosenman into his office. He said that former Governor Gifford Pinchot, of Pennsylvania—long a leader of presidential Republicans—had had a meeting with Willkie recently and then had come in to see the President. Willkie and Pinchot had talked about the possibility of a new setup in American politics. Roosevelt went on, as Rosenman recalled later, “It was Willkie’s idea. Willkie has just been beaten by the conservatives in his own party who lined up in back of Dewey. Now there is no doubt that the reactionaries in our own party are out for my scalp, too—as you can see by what’s going on in the South.

“Well, I think the time has come for the Democratic party to get rid of its reactionary elements in the South, and to attract to it the liberals in the Republican party. Willkie is the leader of those liberals. He talked to Pinchot about a coalition of the liberals in both parties, leaving the conservatives in each party to join together as they see fit. I agree with him one hundred per cent and the time is now—right after the election.

“We ought to have two real parties—one liberal and the other conservative. As it is now, each party is split by dissenters.

“Of course, I’m talking about long-range politics—something that we can’t accomplish this year. But we can do it in 1948, and we can start building it up right after the election this fall. From the liberals of both parties Willkie and I together can form a new, really liberal party in America.”

The President asked Rosenman to go to New York to see Willkie and sound him out on the idea. Rosenman warned his boss that Willkie might interpret the approach as a subterfuge to get him to come out for the President in the election. Roosevelt said that he should explain to Willkie in advance that the project had nothing to do with the coming election.

The two met secretly at the St. Regis—so secretly that Willkie stepped into the bedroom when the waiter served lunch. Willkie was wholly responsive to the idea of a postelection try at party realignment. Both parties were hybrids of liberals and reactionaries, he said. After the war there should be a clear confrontation of liberals and internationalists in one party against conservatives and isolationists in the other. “You tell the President that I’m ready to devote almost full time to this,” he told Rosenman. The two men spent most of two hours going over leaders and groups—labor, racial, and religious groups, small farmers, students, small businessmen, intellectuals, liberal Republicans—who could form the core of a cohesive liberal party. Willkie insisted only that he not see the President until after Election Day.

Roosevelt seemed elated by Rosenman’s report of the discussion. “Fine, fine,” he said; he would see Willkie at the proper time. But without waiting further, and without telling even Rosenman, he wrote to Willkie on July 13 that he would like to see him when he returned from his trip westward. Willkie did not answer the letter; he preferred to wait. He became even more cautious when word spread that the President had written to him; he suspected a deliberate leak by the White House in order to implicate him in Roosevelt’s campaign effort, though he himself had shown the letter to Henry Luce and at least one other friend.

Vast confusion followed as Roosevelt, returning from his Pacific trip, first denied and then admitted that he had asked to see the 1940 nominee. Willkie, backing off, then tried to use former Governor James M. Cox, of Ohio, the Democratic nominee of 1920, to serve as intermediary, but this only confused matters more. The whole question still hung fire when Willkie was hospitalized for heart trouble early in September.

What had happened? Here, Rosenman reflected, were the two most prestigious political leaders in America, two leaders of the world. They were aflame with a great cause—the consolidation of the liberal, internationalist forces in America—that they better than any other men could have conducted with hope of success. And they utterly failed even to begin.

One clue lay in the transformation of Willkie in the last years of his life. The onetime utility tycoon and man of practical affairs had become a passionate ideologue. He had painted his Republican enemies black, calling them reactionary, isolationist, narrow, pathological. He had become aroused not only about isolationism but also about racism at home and abroad. He had read Myrdal and agreed with him that the war was crucial for the future of the Negro, that the race problem was in truth the crisis of American democracy, that the most tragic indignities were those inflicted on Negroes in the armed forces. But above all the author of One World was heartsick over what was happening, in the cloying partisan politics of an election year, to the dream of an effective world organization.

And Roosevelt—what was Roosevelt? To Willkie he was the head of a party as unprincipled as the Republican. The New Deal administration he had often charged with tired and cynical expediency, sacrifice of moral principle, misuse of personal power. Toward Roosevelt he was ambivalent; he had criticized him sharply in his preconvention campaigning, partly to keep his Republican credentials; programatically he was much closer to the President than to the congressional Republican leadership. But Roosevelt’s opportunism put him off. He was so fed up with pragmatic politicians, he wrote to Gardner Cowles in mid-August, that nothing would induce him to serve under any of them. “I’ve been lied to for the last time.”

Was Roosevelt in effect lying to him? Was the whole thing just an election stratagem? Willkie could not tell. On the one hand, the President had seemed willing to try party realignment only after the election. He would naturally want to win re-election as a step toward realizing a grand new party design afterward. And after all, the President had fought his foes in his own party—and in Willkie’s—openly enough; he had even tried to purge conservative Democrats in 1938. But there was a darker side. Roosevelt had put Stimson and Knox in his Cabinet in 1940 without making a sustained effort to win over presidential Republicans. He loved to divide and conquer the GOP at election time. He would be a hard man to work with in overcoming the almost insuperable problems of party realignment. He had put out feelers to Willkie to take other posts; perhaps all these acts were just election gimmicks.

It was hard to say. Better wait until after the election to get really involved, Willkie decided; meanwhile he could put pressure on both candidates and their parties. But on October 8 Wendell Willkie died.

The war would wait for no election, the President had said. Nor would peace. It was Roosevelt’s lot that explosive questions of war and peace dominated both his wartime campaigns. In 1940 the problem had been rearming America and aiding Britain but at the same time promising to keep America out of war. In 1944 the problem was America’s role in maintaining peace and security after the war was won. The President’s management of this problem in 1944—his success in winning a presidential campaign even while the foundations of a controversial postwar organization were being hammered out—was the climactic political feat of his career.

He was still pursuing his idea that nations would learn to work together only by actually working together. Oil, food, education, science, refugees, health—these and many other problems created bridges—and sometimes barriers—between the Allies. UNRRA continued its relief activities under the quiet, devoted leadership of Herbert Lehman; the President’s main role was to help win funds from Congress and to define the jurisdictional line between UNRRA and other relief activities, such as those of the Army and the Red Cross. He took a particular interest in the future of international civil aviation, holding that the air was free but that actual ownership or control of domestic airlines, especially in Latin America, should be in the hands of the governments or the nationals, not of American capital.

Roosevelt generally left the technical aspects of these matters to the corps of presidential advisers and of Civil Service professionals that had risen to peak numbers and talent during the war. But in this election year he kept a careful watch on political implications. No technical problem bristled with more complexities and political dynamite than did international monetary and financial policy.

Planning to prevent postwar monetary chaos had been going on at the Treasury since Pearl Harbor. The chief planner, Harry Dexter White, had long conceived of a United Nations stabilization fund that would enjoin its members both from restrictive exchange controls and from bilateral currency arrangements and would promote liberal tariff and trade policies in order to stabilize foreign-exchange rates; and of a Bank for Reconstruction and Development with enough funds and powers to provide capital for economic reconstruction and relief for stricken people. The British were thinking along somewhat the same lines, though John Maynard Keynes had a far bolder plan, for a Clearing Union that would have no assets of gold or securities but would establish an extensive system of debts and credits making for expansionist pressures on world trade. After endless preliminary discussions a distinguished group of Americans and British, including White and Keynes, in company with Russians, Frenchmen, and others, met amid the meadows and mountains of Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, in July to hammer out agreements.

“Commerce is the lifeblood of a free society,” the President wrote in a greeting to the conference. “We must see to it that the arteries which carry that blood stream are not clogged again.”

The toughest problems were not economic but political. The members of Congress in the American delegation had to be propitiated. The English feared the postwar supremacy of the American dollar even while having to come to terms with it. The Americans could not go along with the unorthodoxy of Keynes’s scheme even though they acknowledged the brilliance, subtlety, economic genius—and occasional insufferability—of the master. The Russians argued stubbornly about their quota of the fund, but Molotov agreed to ease the matter at the eleventh hour. The conference ended with the fund and the bank agreed on, though still needing congressional approval.

Molotov’s flexibility raised hopes about future Soviet collaboration with the West. “There are two kinds of people,” Morgenthau remarked to Roosevelt later, “one like Eden who believe we must cooperate with the Russians and that we must trust Russia for the peace of the world, and there is the school which is illustrated by the remark of Mr. Churchill who said, ‘What are we going to have between the white snows of Russia and the white cliffs of Dover?’ ”

“That’s very well put,” Roosevelt said. “I belong to the same school as Eden.”

The real test was collaboration in keeping the peace after the war was won. By late August, American, British, and Soviet delegates were hard at work, in the stately Harvard-owned Georgetown residence “Dumbarton Oaks,” on the structure of postwar security organization.

The concern of Americans about a new League of Nations had risen to a pitch of both enthusiasm and controversy in the summer of 1944. A host of organizations founded to support a new world order were conducting major publicity campaigns. Wilson, an evocative, highly favorable, and somewhat fictional film about the man who had fought for the League, was packing them in at select movie houses across the nation. Over two-thirds of the voters, according to polls, favored the creation of a new international organization and American membership in it. A cross-section of college students took this position by a ratio of almost fifty to one. Heavy majorities favored giving a world organization military power to preserve peace.

A spate of books on world organization appeared in bookshop windows. Sumner Welles, freed of his State Department responsibilities, argued in The Time for Decision against reliance on military alliances—none in all human history, he said, had lasted for more than a few short years—and for a United Nations that could enforce peace through an Executive Council of eleven members, including Britain, China, the Soviet Union, and the United States as permanent members. The Council, he said, could act only by unanimous agreement of the Big Four and only by a two-thirds vote of the whole Council. Welles’s volume, a Book-of-the-Month Club selection for August 1944, sold almost a half-million copies. Historians and political scientists, including James T. Shotwell, Dexter Perkins, and D. F. Fleming, helped revive the old Wilsonian issues and argued for a new and stronger League. Generally the pundits saw close Big Four unity—especially Soviet-American friendship—as the cornerstone of peace, but they did not always explore the complexity and Realpolitik of big-power relations.

“The intellectuals are nearly all with us,” Roosevelt wrote to a friend, just as they had been in 1920; he pleaded for a grass-roots effort. Actually the intellectuals were as divided as usual, especially between internationalists and “realists.” Theologian Reinhold Niebuhr warned the former against encasing their optimistic view of human nature in leagues and federations; progress could come only after decades of anarchy. Carl Becker wondered How New Will the Better World Be?, since national loyalties and power always had been, and always would be, the essence of international politics. William T. R. Fox, of Yale, contended that agreement among the great powers, especially between Russia and the West, was crucial, and that Soviet co-operation was neither to be assumed nor rejected, but achieved. In The Republic, Charles A. Beard left his fictional internationalist guests speechless after he derided the League of Nations as an effective body and love and morality as ways of running the world. Walter Lippmann’s U.S. War Aims argued that Wilsonian strictures against nationalism were useless, that “we are not gods,” that a world community must evolve slowly from existing nations and communities, that in the middle run the world would be not one but three, with Atlantic, Russian, and Chinese orbits, and that in the short run Washington must boldly co-operate with Moscow, or at least coexist with it.

The books and articles and editorials helped establish the context within which the peace planners worked; so did the presidential campaign. In mid-August Dewey declared that he was deeply disturbed by reports that the Dumbarton Oaks Conference would “subject the nations of the world, great and small, permanently to the coercive power” of the Big Four. A four-power alliance, he said, would be immoral and imperialistic. With Roosevelt’s approval, Hull put out a statement denying that any “superstate with its own police forces and other paraphernalia of coercive power” was being thought of; he denied that the Big Four could coerce other nations. Dewey designated his foreign-policy adviser, John Foster Dulles, to meet with Hull, and after three days of long discussion the two men worked out a statement designed to remove the more controversial aspects of postwar organization from the presidential campaign.

The issue that was cleaving the men at Dumbarton Oaks, however, was not the Big Four against the other nations of the world, but the Big Four against themselves. Early in the proceedings Ambassador Gromyko, head of the Soviet delegation, advanced the principle of Big Four unanimity, and he stuck to it all the days following with might and main. The innocuous word cloaked the momentous proposition that assuming the rule of unanimity an aggressive Big Four power could veto Council action intended to protect a smaller nation or—and this aspect was played down—another Big Four power. The Americans had shifted back and forth on the veto question—they could never forget the specter of Senate isolationism—but at Dumbarton Oaks they took the position that a party involved in a dispute, whether a great power or small, should not be allowed to vote on the question. Gromyko flatly opposed any limitation on the veto, as expected, but then he threw a bombshell into the sedate mansion by demanding that all sixteen of the Soviet republics be seated in the new organization.

February 4, 1944, C. K. Berryman, courtesy of the Washington (D.C.) Star

“My God!” exclaimed Roosevelt when Stettinius told him of the request. He asked the Undersecretary to inform Gromyko that such a proposal—labeled “X matter” to keep it from becoming known—would end the chances of the new United Nations being accepted by the Senate or the American people. Actually, the sixteen-vote proposition seemed so preposterous to Roosevelt that he expected to talk Stalin out of it. The veto was another matter. The more the Anglo-Americans opposed it, the more Gromyko insisted on it. Stettinius, convinced that solving the veto question was crucial to the whole enterprise, decided to bring out his “biggest and last remaining gun.” Would the President talk with Gromyko? Would Gromyko, the President asked the Undersecretary, be offended if he received him in his bedroom? Stettinius thought he would be impressed.

It was an odd encounter the next morning between the President in his old bathrobe and the dark, personable young Ambassador. After chatting breezily, Roosevelt turned to the main issue, noting that traditionally in his country husbands and wives in trouble could state their case but not vote on it. He dwelt at length on old American concepts of fair play. Gromyko was pleasant but unyielding. Roosevelt then proposed a cable to Stalin reiterating his argument. That was up to him, Gromyko said. The President sent a friendly but strongly worded cable to the Marshal. Almost a week later the reply came back. The basic understanding was the unanimity of the Big Four. That presupposed no room for suspicion among the major powers. He could not ignore, said Stalin, certain absurd prejudices hindering an objective attitude toward the Soviet Union.

So deadlock had been reached on preserving the peace even as Soviet and Anglo-American troops were winning it. The Russians were still insisting on their sixteen votes. The Dumbarton Oaks meeting adjourned with the shining structure of a new international organization agreed on, but with a dark cloud over the capacity of the great powers to order their own relationships.

In mid-September 1944 Roosevelt and Churchill and the Combined Chiefs met again in Quebec for another conference, this one essentially military. The scene was the same as before, with Roosevelt and Churchill quartered in the Citadel and their staffs in the Chateau Frontenac, perched high on the north bank of the St. Lawrence, but the situation was radically different. Churchill and Roosevelt met as victors. Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt greeting the Churchills at the station seemed more like the reunion of a happy family than a gathering of world leaders.

Out of ever-increasing solidarity and friendship, Roosevelt said at the start of the conference, had come prospering fortune. Though no one could yet forecast when the war with Germany would end, it was clear that the Germans were withdrawing from the Balkans, and it seemed likely in Italy that they would retire to the Alps. The Russians were at the point of invading Hungary. In the West the Germans probably would retire to the Rhine, which would be a formidable rampart. In Asia, the President went on, the American plan was to regain the Philippines and to control the mainland from there or Formosa, and from bridgeheads that would be seized in China. If forces could be established on the mainland of China, China could be saved.

“Everything we have touched has turned to gold,” Churchill summed it up in his own equally favorable review of the situation.

These heady successes helped the conferees debate some of the old issues in relaxed fashion. No longer was the Mediterranean a source of contention; the Americans were willing to leave their troops in Italy until the Germans were defeated or pushed out. Churchill now spoke more freely of Vienna as a key objective, after giving the Germans a “stab in the Adriatic armpit,” and the American Joint Chiefs were now less hostile to an amphibious landing on the Istrian Peninsula and even willing to bequeath landing craft to General Wilson for that possibility.

The sharpest turnabout was on Pacific strategy. Gone were the days of trying to limit the diversion of troops and ships to the amphibious attack against Japan; now the British wanted to play their full part. Japan, Churchill told the plenary session, was as much the bitter enemy of the British Empire as of the United States. He proceeded to offer the British main fleet to take part in the major operations in the central Pacific under American command. A detachment could operate under MacArthur if desired, and he also proffered RAF bombers. The Prime Minister knew that King and other admirals were cool to the idea, so he pressed for a showdown while Roosevelt was present. Could he have a definite undertaking about using the British fleet in the main operations against Japan?

“I should like,” Roosevelt said vaguely, “to see the British fleet wherever and whenever possible.” King said that the matter was being studied.

“The offer of the British fleet has been made,” Churchill persisted. “Is it accepted?”

“Yes,” the President said.

“Will you also let the British Air Force take part in the main operations?” Marshall answered that not so long ago “we were crying out for planes—now we have a glut.”

Evidently the British could not break into the American preserve in the Pacific without a bit of hazing. But Pacific planning still turned largely on the progress of the war in Europe. At the time of the Quebec meeting the Combined Chiefs had high hopes, based on Intelligence estimates, that the Germans would surrender within twelve weeks. Though the President was not so optimistic, it seemed high time to reach final agreement on occupation zones. Roosevelt had long opposed the earlier plan that the British occupy northwest Germany and the Low Countries and the Americans southern Germany, Austria, and France; “I am absolutely unwilling to police France,” he had exclaimed. But now at Quebec he changed his mind and approved the original plan, partly because the British agreed that the Americans could control Bremen and its port of Bremerhaven in order to supply their forces.

Long-run policy for Germany was a harsher problem. For weeks Morgenthau, Hull, and Stimson had been debating the treatment of Germany after its surrender. Stimson was willing to punish the Nazi leaders, destroy the German Army, and perhaps partition Germany into north and south sections and internationalize the Ruhr, but he did not want to destroy raw materials and industrial plant crucial to European recovery. Morgenthau was burning to diminish and fragmentize Germany, dismantle and move out all plants and equipment, close the mines in the industrial heartland, and take control of education and publishing. Hull at times seemed to favor a punitive policy, at other times a softer one, but always a State Department role. Roosevelt talked tough at times—he wrote to Stimson that the Germans should be fed from army soup kitchens for a while—but on policy he wavered among his contending advisers. His central guideline seemed to be that the German people as a whole were responsible for a lawless conspiracy and must be taught a lesson.

Summoning Morgenthau to Quebec, Roosevelt asked him to present his proposals on Germany. As the Secretary spoke, he could hear and see “low mutters and baleful looks” from the Prime Minister. Churchill had never been more irascible and vitriolic, Morgenthau remembered later, as, slumped in his chair, he let loose the full flood of his biting, sarcastic rhetoric. He looked on the Treasury plan, he said, as he would on chaining himself to a dead German. The President sat by saying little. The next day, in a less negative mood—because he wanted Morgenthau’s help on Lend-Lease matters, perhaps, or, even more, because he had been persuaded that Britain would gain economically from a deindustrialized Germany—Churchill dictated a statement which he and Roosevelt initialed. It went far in Morgenthau’s direction.

“The ease with which the metallurgical, chemical and electrical industries in Germany can be converted from peace to war has already been impressed upon us by bitter experience. It must also be remembered that the Germans have devastated a large portion of the industries of Russia and of other neighboring Allies, and it is only in accordance with justice that these injured countries should be entitled to remove the machinery they require in order to repair the losses they have suffered. The industries referred to in the Ruhr and in the Saar would therefore be necessarily put out of action and closed down….

“The program for eliminating the war-making industries in the Ruhr and in the Saar is looking forward to converting Germany into a country primarily agricultural and pastoral in its character.”

Eden, who had flown to Quebec from London, was shocked by the statement. “You can’t do this,” he exclaimed to Churchill. “You and I have said quite the opposite.” A testy quarrel broke out between the two while Roosevelt looked on silently. The Morgenthau plan, it was clear, had an aptitude for dividing people. Stimson had hotly opposed it, Hull would soon turn against it, Churchill eventually would repudiate it, and Roosevelt would quietly back away.

The Quebec Conference, which had opened in a “blaze of friendship,” in Churchill’s words, closed amicably because of agreed-on military matters. Soon after, Churchill visited Roosevelt at Hyde Park for final discussions. Leahy and others sat by enthralled at lunch the second day while Churchill and Eleanor Roosevelt debated long-run peace strategy—the First Lady contended that peace could best be established by improving living conditions throughout the world, Churchill that it would be kept best by an agreement between Britain and the United States to prevent war if necessary by using their combined forces. Roosevelt was largely silent. He was more interested in the military plans for the short-run than philosophical questions about the long-run.

But even as Roosevelt was bidding Churchill good-by, reports were coming in of German resistance that lowered hopes for victory by year’s end and vitiated some of the military planning of the second Quebec Conference.

The Presidential Room of the newly built Hotel Statler, in Washington, September 23, 1944. Hundreds of union men, Democratic politicos, and Washington officials pushed back their chairs from their dinner tables. At the head table sat Franklin Roosevelt, flanked by Daniel J. Tobin, of the Teamsters, AFL chief William Green, ship-maker Henry Kaiser. The President was framed by an array of microphones in front of him and a star-spangled curtain behind. Tobin introduced his guest. The room broke into a storm of applause, which died down only to erupt again and again as the President threw his head back and grinned.

Finally the room quieted. There was an air of expectancy. All had heard the rumors of Roosevelt’s illness—the pictures from San Diego, the sound of his voice from Bremerton, the long delay while Dewey had campaigned across the nation. Did the old campaigner still have it? During dinner, at a table of Roosevelt’s family and friends, Anna Roosevelt Boettiger leaned over and asked Rosenman: “Do you think that Pa will put it over?…If the delivery isn’t just right, it’ll be an awful flop.”

Roosevelt began to talk. Then a surprise—he was still sitting down. The first words seemed to come strangely, as though the President were mouthing them.

“Well, here we are—here we are again—after four years—and what years they have been! You know, I am actually four years older, which is a fact that seems to an-noy some people. In fact, in the mathematical field there are millions of Americans who are mo-o-o-re than eleven years older than when we started to clear up”—now his words quickened and sharpened—“the mess that was dumped into our laps in 1933.”

A burst of clapping, shouting, table pounding. Roosevelt proceeded to deride those who attacked labor for three and a half years in a row and then suddenly discovered they really loved labor and wanted to protect it from its friends. The Republicans who approved New Deal laws in their Chicago platform, he taunted, would not recognize those progressive laws if they met them in broad daylight.

“Now, imitation may be the sincerest form of flattery—but I am afraid—I am afraid—that in this case it is the most obvious common or garden variety of fraud.

“Of course, it is perfectly true that there are enlightened, liberal elements in the Republican Party, and they have fought hard and honorably to bring the Party up to date and to get it in step with the forward march of American progress. But these liberal elements were not able to drive the Old Guard Republicans from their entrenched positions.

“Can the Old Guard pass itself off as the New Deal?

“I think not.

“We have all seen many marvellous stunts in the circus but no performing elephant could turn a hand-spring without falling flat on its back.”

The President reviewed labor’s record, and his own. It was his old New Deal pitch given a new wartime sheen. He recited the statistics of progress, poked fun at the Republicans for trying to play general, denounced labor baiters, and stated that the occasional strikes that had occurred had been condemned by all responsible labor leaders but one. “And that one labor leader, incidentally, is certainly not conspicuous among my supporters.”

Roosevelt was in full stride now. Raising and lowering his voice, drawing out his words and sentences, chuckling over some of the more incredible charges of the opposition, he derided Republicans for hating to see workers give a dollar to “any wicked political party” while monopolists gave tens of thousands; chastised them for making it hard for soldiers and sailors overseas and for merchant seamen to vote; reminded his audience of the “Hoovervilles” of 1933; and accused his foes of imitating Hitler’s technique of the big lie—especially in the allegation that it was not a Republican but a Democratic depression from which the nation had been saved in 1933.

“Now, there is an old and somewhat lugubrious adage which says: ‘Never speak of rope in the house of a man who has been hanged.’ In the same way, if I were a Republican leader speaking to a mixed audience, the last word in the whole dictionary that I think I would use is that word ‘depression.’ ”

By now his listeners in the ballroom were not merely cheering—they were laughing. Anna’s fears were stilled. Not only were Roosevelt’s lines funny, but he was delivering them with such inflection, emphasis, alternation of deadpan innocence and rolled-up eyes of mock amazement, biting ridicule, and gentle sarcasm that the clapping was drowned in uncontrollable belly laughter.

Then the dagger thrust, planned by Roosevelt long before, the blade lovingly fashioned and honed, now delivered with a mock-serious face and in a quiet, sad tone of voice, rising briefly to indignation.

“These Republican leaders have not been content with attacks—on me, or my wife, or on my sons. No, not content with that, they now include my little dog, Fala. Well, of course, I don’t resent attacks, and my family doesn’t resent attacks, but”—a pause, and then quickly—“Fala does resent them.

“You know—you know—Fala’s Scotch, and being a Scottie, as soon as he learned that the Republican fiction writers in Congress and out had concocted a story that I had left him behind on an Aleutian Island and had sent a destroyer back to find him—at a cost to the taxpayers of two or three, or eight or twenty million dollars—his Scotch soul was furious. He has not been the same dog since. I am accustomed to hearing malicious falsehoods about myself—such as that old, worm-eaten chestnut that I have represented myself”—he chuckled—“as indispensable. But I think I have a right to resent, to object to libellous statements about my dog.”

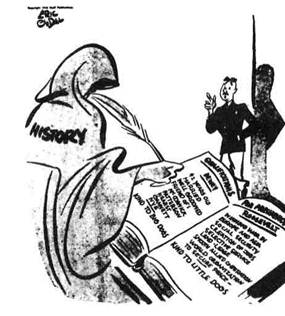

October 24, 1944, Eric Godal, PM, reprinted by courtesy of Field Enterprises, Inc.

The President went on for a bit, but he had already answered the big question in the minds of his listeners. In 1940 Roosevelt had said, “I am an old campaigner and I love a good fight.” Clearly four years later he still did. This was not one of those speeches that took on importance only in later perspective. It had immediate impact. Reporters traveling on Dewey’s campaign train in California heard the speech in the press car and instantly recognized its importance. Dewey felt that the “snide” speech was designed to anger him, and it did. He decided to campaign more aggressively.

After his opening strike the President returned to a stance of nonpartisan Chief Executive for four weeks. His only political speech was a fireside chat urging people to vote and rebutting charges that his administration was Communist-dominated. Meantime his political aides readied final plans. Roosevelt’s basic strategy had long been set. As in the past he would appeal to liberal and internationalist Republicans, accuse Dewey of being controlled by his congressional party, and seek to hold the support of his own congressional party, especially in the South, while mobilizing voting power in the big cities.

This strategy was standard and time-tested; more serious was the operational problem. Early in the year, Louis H. Bean, a statistician and political buff, had given to Hopkins, Hannegan, and Hillman a long analysis of voting turnout in relation to Democratic gains and losses. He found that Democratic setbacks in 1942 and 1943 were due not to Republican popularity but to a fall-off in participation. Almost invariably the Democratic percentage shrank with lower participation. This was true in big cities; it was true in less urban areas such as Roosevelt’s own Dutchess County. Bean’s verdict was conclusive: “Participation…is of crucial importance for the Democratic Party in 1944.”

The trouble was that the very people who tended to vote Democratic—low-income groups, young people, Negroes, women, ethnic elements—tended also to show the poorest turnout. If the year had been 1936 the President might wage a rousing and militant campaign that would draw at least some of the apathetic to the polls. But in 1944 many people, no matter how concerned, could not vote because they had crossed state lines and were not registered, or were in the service, or were working long hours in remote army bases and war plants. And Roosevelt had no thought of waging an inflammatory campaign during war.

The alternative was to rely on organization, and here, too, the President faced a dilemma. Except in Albany and Chicago and a few other cities the Democratic party was fragmented, locally oriented, or even moribund. By far the strongest national political machine in the summer of 1944 was Sidney Hillman’s CIO Political Action Committee. The PAC was organized nationally and regionally and down to ward and precinct committees; it had gifted leadership in Hillman, political and propaganda talent, considerable money, ideas, energy, and conviction.

It was also the main target for Republican attack. Following the Democratic convention—where Roosevelt was said to have had Truman’s nomination checked out with the labor leader—“Clear It With Sidney” had become a Republican war cry. CLEAR EVERYTHING WITH SIDNEY was placarded across the nation. “Sidney Hillman and Earl Browder’s Communists have registered,” voters were told. “Have you?”

The big open Packard, its canvas top down despite the drizzle, drove out onto Ebbets Field and up a ramp. The President of the United States was helped out of the car. Locked in his braces, he stood before a small crowd, doffed his old gray campaign hat, let his blue-black Navy cape fall from his shoulders. He had never seen the Dodgers play, he told the crowd, but he had rooted for them. The rain plastered down his hair and splattered on his pince-nez. He paid a tribute to Senator Bob Wagner—“we were together in the legislature—I would hate to say how long ago”—and asked that he be returned to the Senate. It was pouring by the time he was eased back into the car. He was given a rubdown and dry clothes at a nearby Coast Guard motor pool. Then the ordeal resumed.

Its top still down by the President’s order, the limousine led a long cavalcade through Queens to the Bronx, then to Harlem and mid-Manhattan and down Broadway. La Guardia and Wagner sat on jump seats in front of the President; Eleanor Roosevelt was in the procession behind. The cold rain came down relentlessly, drenching the President’s upflung arm and sleeve, rolling off his fedora, circling the lines of the grin on his face, seeping into his coat and shirt. Sidecar motorcycles flanked the Packard; guards stood on its running boards; three limousines packed with Secret Service men followed. Hour after hour the procession continued in the downpour. People waited under umbrellas and soggy newspapers to catch a glimpse of the big smile. At his wife’s apartment in Washington Square he changed again and rested.

That evening the President spoke to the Foreign Policy Association in the grand ballroom of the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel on Park Avenue. It was a long catchall speech in which he again attacked the congressional Republicans for their isolationist voting, extolled liberal and internationalist Republicans—especially Henry Stimson, who was sitting on the dais—and warned that the likes of Joe Martin and Ham Fish would have controlling power in Congress if the Republicans won. But toward the end he took a stand on the crucial issue of the peace-keeping of the new United Nations.

“Peace, like war, can succeed only where there is a will to enforce it, and where there is available power to enforce it.

“The Council of the United Nations must have the power to act quickly and decisively to keep the peace by force, if necessary. A policeman would not be a very effective policeman if, when he saw a felon break into a house, he had to go to the Town Hall and call a town meeting to issue a warrant before the felon could be arrested.

“So to my simple mind it is clear that, if the world organization is to have any reality at all, our American representative must be endowed in advance by the people themselves, by constitutional means through their representatives in the Congress, with authority to act.

“If we do not catch the international felon when we have our hands on him, if we let him get away with his loot because the Town Council has not passed an ordinance authorizing his arrest, then we are not doing our share to prevent another world war….”

The day in New York was a double triumph for the President. His four-hour, fifty-mile drive through the city was his answer to charges of loss of health and stamina. To be sure, anti-Roosevelt newspapers, including the Daily News, could run pictures showing him looking tired and worn, with sallow, lined face, but perhaps two million people had seen that uplifted arm and radiant smile. And in his speech that evening he outflanked Dewey on the issue of peace-keeping. Republican Senator Joe Ball, protégé of Harold Stassen, who was still serving in the South Pacific, promptly endorsed Roosevelt on the ground that while Dewey had evaded the issue, Roosevelt had met squarely and unequivocally the central question on which the isolationists had kept America out of the League of Nations.

Six days later Roosevelt carried his campaign to Philadelphia. Once again he toured city blocks for hours in an open car and once again it rained. In the city of brotherly love he talked of war—of his efforts to rebuild the Navy before Pearl Harbor, of the obstruction of the Republicans, of the people who laughed at his call for 50,000 planes a year, of the strategy he had followed in the war, of war supply and logistics and personnel. For once he mentioned his four sons at war: “I can speak as one who knows something of the feelings of a parent with sons who are in the battle line overseas.” He promised categorically—in response to charges by Dewey—that servicemen would be returned to their homes promptly after the war—“And there are no strings attached to that pledge.”

Two years before, the successful invasion of Africa had not been launched until after the congressional elections. Now Roosevelt’s luck returned. On October 21 MacArthur had landed with his troops on Leyte, in the central Philippines, announced on the beach, “I have returned,” and asked Filipinos to rally to him and to “follow in His name to the Holy Grail of righteous victory.” Roosevelt could not let the opportunity pass. “I think it is a remarkable achievement,” he told the throng in Shibe Park, “that within less than five months we have been able to carry out major offensive operations in both Europe and the Philippines—thirteen thousand miles apart from each other.

“And speaking of the glorious operations in the Philippines—I wonder—whatever became of the suggestion made a few weeks ago, that I had failed for political reasons to send enough forces or supplies to General MacArthur?”

He quoted a “prominent Republican orator” as calling “your present Administration” the “most spectacular collection of incompetent people who ever held public office.” “Well,” said the President, “you know, that is pretty serious, because the only conclusion to be drawn from that is that we are losing this war. If so, that will be news to most of us—and it will certainly be news to the Nazis and the Japs.”

The following night Roosevelt spoke from his car in Soldier Field in Chicago. Nobody there that night would ever forget it, Rosenman said later. Over 100,000 people packed the stadium; another 100,000 or more waited outside. A cold wind was blowing in from the lake; Roosevelt’s words bounced off the far sides of the stadium and back; but somehow he held the crowd.

It was the strangest campaign he had ever seen, the President said. He quoted the Republicans as saying that the “incompetent blunderers and bunglers in Washington” had passed excellent laws for economic progress; that the “quarrelsome, tired old men” had built the greatest military machine the world had ever known—that none of this would be changed—and “Therefore it is time for a change.”

“They also say in effect, ‘Those inefficient and worn-out crackpots have really begun to lay the foundations of a lasting world peace. If you elect us, we will not change any of that, either.’ ‘But,’ they whisper, ‘we’ll do it in such a way that we won’t lose the support even of Gerald Nye or Gerald Smith—and this is very important—we won’t lose the support of any isolationist campaign contributor. Why, we will be able to satisfy even the Chicago Tribune.’ ”

The President spoke mainly about the economic past and future. He recited the entire economic bill of rights of the previous January. He promised “close to” sixty million productive jobs. He talked about homes, hospitals, highways, parkways, of thousands of new airports, of new cheap automobiles, new health clinics. He proposed that Congress make the FEPC permanent; that foreign trade be trebled after the war; that small business be aided; that the TVA principle be extended to the Missouri, Arkansas, and Columbia River basins. He expressed his belief in free enterprise and the profit system—in “exceptional rewards for innovation, skill, and risk-taking in business.”

For Dewey, too, it was a strange campaign. Like his predecessors Willkie and Landon and especially Hoover, he found it impossible to come to grips with his adversary. He had plenty of hard evidence for his charges of mismanagement and red tape and expediency—but words meant little in the face of MacArthur’s and Eisenhower’s triumphs abroad. He was infuriated by Roosevelt’s bringing up the question of enforcing the peace—a question he had understood to be barred from the campaign in the interest of bipartisan unity. He had occasional strokes of luck, such as Selective Service Director Hershey’s remark that the government could keep people in the Army about as cheaply as it could create an agency for them when they came out. But Roosevelt was quick to have Stimson shush up Hershey and to make clear his own plans for rapid demobilization.