Genetically modified organisms (GMOs) have permeated our homes, our supermarkets, our fast-food joints, and our fine restaurants. Trying to avoid them is an important task, but it is practically a full-time job these days. This chapter will outline some ways you can lower your risk of consuming GMOs—and the risk of feeding them to your children.

Certain foods are more likely to be GMO than not. So be particularly careful when considering whether to buy or eat these items: soy products or soybeans, corn, canola, cottonseed, and sugar beets. Let’s take a look at each of these foods to see how they are affected by GMOs.

Soybeans: Soybean plants are genetically modified when a gene is taken from bacteria (Agrobacterium sp. strain CP4) and inserted into the soybean plant. This makes the plants more resistant to herbicides. The USDA says that 91 percent of soybeans grown in the United States are genetically modified. There are lots of products made from soybeans, including soy flour, soy isolates, soy lecithin, and soy protein. Also, be careful with soy-based products such as tofu, soy milk, and edamame. Most breads contain soy (in the form of lecithin or other dough conditioners). Fresh fruits and vegetables are sometimes sprayed with a waxy coating made of soy. When it comes to processed foods, including luncheon meats, keep an eye out for these terms, which are often code for GMO soy: natural flavor, vegetable oil, and vegetable broth. Oh— and the aspartame in your Diet Coke is made using a fermentation process that involves GMO soy and corn. But the pervasiveness of GMO soybeans doesn’t mean there are no organic soybean foods available; just keep reading those labels.

Com: About 73 percent of US corn is genetically modified. There are three basic varieties of GMO corn. Two types have been genetically modified to kill the insects that eat them, and the third variety was designed to tolerate Monsanto’s Roundup herbicide. GMO corn is typically present in high-fructose corn syrup, an ingredient in many processed foods, such as corn flakes and corn chips. Also watch out for corn starch, corn oil, and corn syrup. In addition, GMO corn is often fed to cattle and other livestock, so when you eat beef, pork, or poultry, you may be a secondhand consumer of GMO corn. So, think about opting for grass-fed or free-range livestock. Michael Pollan put it well in his 2006 book, Omnivore’s Dilemma:

Corn is in the coffee whitener and Cheez Whiz, the frozen yogurt and TV dinner, the canned fruit and ketchup and candies, the soups and snacks and cake mixes, the frosting and gravy and frozen waffles, the syrups and hot sauces, the mayonnaise and mustard, the hot dogs and bologna, the margarine and shortening, the salad dressings, and the relishes, and even the vitamins.

Canola and Cottonseed: Both of these food items have been modified to resist pests and are fairly prevalent in our food. About 87 percent of cotton (which is made into cottonseed) is GMO, and roughly 75 percent of canola is GMO. Cotton seeds are pressed into cottonseed oil, which is a common ingredient in vegetable oil and margarine; to play it safe, opt for extra virgin olive oil instead.

Sugar Beets: A new concern, GMO sugar beets are becoming more common. According to the USDA, only about 60 percent of sugar beets were GMO in 2008–2009, but the following year, GMO varieties accounted for about 95 percent of sugar beets. And food processors are finding that it’s cheaper to get their refined sugar from sugar beets than from cane sugar, so sugar beets are becoming more common. So, if an ingredient is listed as “sugar,” not “pure cane sugar,” it’s a good bet there’s some sugar beet in there. Again, check those labels and remember: if it’s not marked as “organic,” it isn’t.

Artificial Sweeteners: Be careful, especially, of aspartame (also known as NutraSweet and Equal or “the little pink or blue packets”), which is created in part by genetically modified microorganisms. And with today’s emphasis on weight loss, these sweeteners appear in more than six thousand products, including soft drinks, gum, candy, desserts and mixes, yogurt, tabletop sweeteners, and even some vitamins and sugar-free cough drops.

Some Other Vegetables: Certain vegetables are commonly GMO (unless labeled otherwise). These include Hawaiian papaya, zucchini, and yellow squash. Always check the labels.

And more: Also, keep an eye out for honey and bee pollen, which may have been gathered from GMO plants.

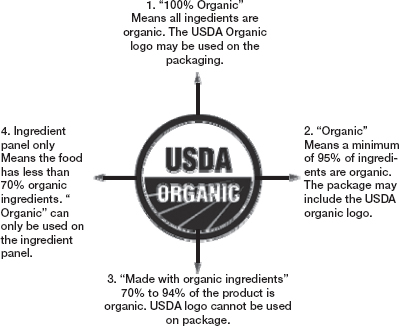

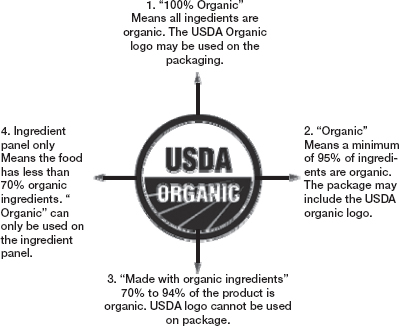

Reading the labels isn’t always as easy as it sounds. Labeling isn’t always as clear as youd like. Just remember that the USDA organic seal shows that the product is certified organic and has at least 95 percent organic content. For products with multiple ingredients, such as bread or soup, a USDA organic seal means that each of the ingredients listed has been certified as organic.

Basically, there are three types of organic labels:

1. When a label says “100% organic,” it means all ingredients are organic.

2. “Organic” means that at least 95 percent of the ingredients are organic. The other 5 percent, though, must also be non-GMO.

3. “Made with organic (ingredient name).” This label means that at least 70 percent of the ingredients are organic; the remaining 30 percent must be non-GMO.

If the term organic is only in the list of ingredients and not anywhere else on the package, then there is no required overall percentage for organic ingredients in the product, and any nonorganic ingredient may be GMO. Just to make things more complicated, the USDA allows several other voluntary labels for livestock products, such as meat and eggs. USDA’s Food Safety Inspection Service verifies the truthfulness of these claims:

• Free-range: This refers to cows that lived in a building, room, or area with unlimited access to food, fresh water, and continuous access to the outdoors during their production cycle. Sometimes the outdoors area is fenced-in or netted-in, sometimes not.

• Cage-free: Here, cows were allowed to freely roam a building, room, or enclosed area with unlimited access to food and fresh water during their production cycle.

• Natural: Beef, poultry, and egg products labeled as “natural” must be “minimally” processed and cannot contain artificial ingredi ents. But this label doesn’t say anything about farm practices, only about the processing of the meat or eggs.

• Lean or extra-lean: These terms, as defined by the USDA, specify how much fat is in each gram of beef. Specifically, “lean” means 100 grams (3.5 ounces) of beef must have fewer than 10 grams of fat, 4.5 grams or less of saturated fat, and fewer than 95 milligrams of cholesterol. “Extra lean” means that 100 grams of beef must have fewer than 5 grams of fat, fewer than 2 grams of saturated fat, and fewer than 95 milligrams of cholesterol.

• Hormone-free: There is no certification for this category, though beef labeled “organic” or “grass-fed” must be hormone-free, as certified by the USDA. But if it is just labeled “hormone-free” (and lacks the USDA organic seal), there’s no way to know what’s in the food.

If that wasn’t confusing enough, there are also some labels that don’t really provide any information beyond, perhaps, good intentions. Don’t be fooled by them. They include:

• Pasture-raised: There’s no USDA definition here; the meat industry can use it as it wishes, without government regulation.

• Natural: According to the USDA, a natural product contains “no artificial ingredient or added color and is only minimally processed.” Processing cannot fundamentally change the product, and the label must include a specific explanation such as “no artificial ingredients; minimally processed.” Incidentally, all fresh meat qualifies as natural; the term says nothing about open space, food (organic or otherwise), or added hormones or antibiotics.

• Humane: Again, this is an unregulated label.

• No added hormones: Federal regulations have never permitted hormones or steroids in poultry, pork, or goat, so this label simply means the producer followed the basic USDA regulations for sale in the United States.

In short: stick with grass-fed beef, though organic would also be fine.

Egg packaging also has its own language. Here are the most common terms:

• Cage-free: This term means that the hens don’t live in cages. But that doesn’t mean that they have the run of the yard. The American Humane Certified label identifies some, but not all, cage-free eggs.

• Free-range: The USDA certifies that the poultry has been “allowed access to the outside,” but does not specify the quality or size of the outside area, nor how much time a given hen gets out there in the open.

Those little stickers on fruits and vegetables actually have a purpose, besides making it hard to wash the foods carefully. They are called price look-up (PLU) codes, and they contain numbers that cashiers use to ring you up at the register. These codes aren’t mandatory, but they’re pretty common, because it makes it easier at the check-out counter. In addition to pricing information, though, these codes provide important information about the product you are buying, at least within the United States. You just need to know what those little numbers mean. According to consumer reports, the first step is to count the number of digits in the code. Then you look at the first digit in the code. Here’s a cheat sheet:

• If there are five digits in the code and the first one is a 9, then the item is organic. For instance, small, organic lemons are coded 94033.

• If there are five digits in the code starting with an 8, the item is GMO.

• If there are four digits, starting with a 3 or 4, the product is probably conventionally grown. Small, “regular” lemons, for example, are labeled 4033.

Try to use mostly foods that you cook and prepare yourself. Avoid anything that comes in a box or a bag. If you’ve cooked it, you probably know what’s in it. (We hope.) And when you’re cooking, think about how you cook. Make sure you’re using a GMO-free cooking oil. Soy, cottonseed, canola, butter, and corn oils often contain genetically modified organisms, unless they’re labeled as organic. Extra virgin olive oil is probably safest, but— again—read the label.

Most GMO food comes from large, industrial farms, so smaller, local farmers might provide safer food. And there are plenty to choose from; according to Local Harvest, a nonprofit organization devoted to encouraging people to buy locally, there are almost two million farms in the United States, most of them small and family owned. Of course, there’s no clear definition of “local”; in densely populated areas, it’s pretty nearby, while rural people are often willing to travel a little farther to reach a “local farm.” Also, remember that imported produce often contains more pesticides than domestically grown. If you can’t find produce within the county, at least stick to the US borders.

Shopping locally may also allow you to speak to the farmer and find out how the farm operates, and whether it uses GMOs. (And maybe even encourage a change in their approach...) Studies show that more than half of the people (about 58 percent) who shop locally do so because they like to know where their food comes from. People also figure they’re getting improved quality and freshness of the food items (82 percent) and providing support for the local economy (75 percent).

Local food markets are a growing phenomenon. There are more farmers’ markets than ever before. The number of farmers’ markets hit 5,274 in 2009, up from 2,756 in 1998, according to the USDA. Sales are up, too. In fact, direct-to-consumer marketing represented about $1.2 billion in current dollar sales in 2007, according to the 2007 Census of Agriculture, compared with $551 million a decade earlier.

If you grow it, you know whether you used organic or GMO seeds, you know what fertilizer did—or did not—go on your plants. And you’d probably know if you sprayed the plant with an herbicide or pesticide. If you have more space, say a side or backyard, you can plant vegetables in seasonal rotation; there’s nothing like picking a tomato, then going inside to cut it up for a very fresh salad. It’s probably more of a challenge for city folks. If you only have a little space for “farming,” use a planter on the windowsill or balcony to grow herbs and fruit trees.

Children often like growing food, too. Even preschoolers can become quite proficient at knowing which vegetables to pick. Some easy-to-grow plants are radishes, herbs, and peas, and once you experience success, you might find you want to branch out to other beloved fruits and veggies. Most important, children who grow their own vegetables often have a good understanding about the connections between soil, food, and their own health. Role modeling is always the best way to teach. And if a child grew the veggies, he or she might be more apt to eat them when they appear on the dinner plate.

Start by picking restaurants that cook meals from scratch and don’t use packaged, processed mixes and sauces; these are more likely to have GMO ingredients. Fast-food and chain restaurants are more likely to be problematic than mom-and-pop places.

Don’t be afraid to ask questions, especially if it’s a restaurant you go to regularly. If there’s a knowledgeable server or chef, that person can guide you through the menu to help you avoid GMO foods. Ask about what type of cooking oil they use at the restaurant. Usually, when someone tells you they use vegetable oil or butter, they’re talking about soy, cottonseed, canola, or corn oil. These are often GMO—unless they are certified organic. Olive oil is probably safest, but be careful that it’s not a blend; some restaurants mix canola and olive oils.

The good news is that once you’ve been through a menu, you probably won’t need to ask a second time. Chances are the restaurant won’t suddenly switch from organic to GMO—especially if they know the customers are watching. And you told them that! Also, by showing the restaurant that you care about what is in the foods you order and eat, the owner or chef might be more likely to try to avoid genetically modified ingredients in the future.