I joined 3rd Battalion / 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment (Airborne) in late March, 1990. The 160th is nicknamed “The Nightstalkers.” The unit provides special operations aviation for the various Special Forces and Ranger units of the different branches of the military. The unit motto is “Nightstalkers Don’t Quit,” NSDQ for short. We always had training activities going on, such as fast rope training (when a soldier slides down a rope out of a helicopter), shooting the different weapons at the ranges, or doing a 5-mile run on a Friday morning. The unit would deploy to locations both in the United States and overseas to provide special operations aviation support. As a medic in the unit, my job was primarily to provide medical care to the members of the unit. The role has evolved since Desert Storm, and now the medics provide care to other Nightstalkers, but as a secondary mission. We also provided emergency casualty evacuation care for our customers – the people that the unit provided air support for. The unit could also do emergency medical extractions and combat search and rescue missions. The other element of being a Nightstalker medic was the paratrooper side. We jumped out of airplanes to provide medical support for members of the Forward Area Refueling Point or FARP team. Originally, we had only one medic on jump status when I first joined the unit, so typically only our sergeant was on jump status. I went on jump status in January, 1992. We trained hard as a medical section; our sergeant made us go on many forced road marches and from time to time he would tie a rope to our military gear so we would stay together as a unit. We went on what we called “mud runs” – our section would go running in the woods through the swamps in our physical fitness uniform and boots.

My first training mission overseas with the 160th was to Panama in the fall of 1991. Part of the unit went to Honduras to train, and the other half went to Panama. We had a small aid station set up in case anyone got sick. I went up a few times with the Blackhawk helicopters to shoot the mini guns, and I also had the opportunity to go on a training mission with the refueling team. The refueling team was supposed to set up a landing zone so five helicopters could land and drop off soldiers. The sergeant in charge told me later that the whole mission brief was fictitious. We were really going on patrol that night in the jungle. The team would receive a call that the landing zone was “compromised,” so the team would have to escape and evade. We were going to walk around in the jungle for a while and then take boats back to the “safe area.” I was on the ground and watched the team parachute in. We started our patrol to where they were going to set up the landing zone. After the team set up the landing zone, a call came on the radio that we had to escape and evade. I knew this all the time, but I played along. We started our patrol in the jungle again. It was dark and hot, and we walked through warm swamp water about knee high. One of the soldiers slipped and fell into the swamp.

He was carrying the squad automatic weapon, or SAW. I had to keep a closer eye on this guy now, and we all took turns carrying the extra weapon. A few kilometers later, he slipped again. This time he passed out and he fell head first into the murky swamp water. I saw bubbles coming up as he was submerged in the water. We all ran to him to prevent him from drowning; he was completely out of it. We quickly found some dry land and I went to work. I checked his airway, breathing, and circulation. I started an IV and decided he needed to be evacuated. The team had to set up a landing zone for real now; helicopters don’t like landing in swamps. The helicopter took 30 minutes to arrive. I was going to go with the soldier on the helicopter, because our other medic had arrived. I had done everything I could for the guy; I was worried that he had swallowed swamp water and that some of it had gotten into his lungs. This could kill him; the jungle in Panama is wild and unforgiving. The medic in this helicopter was surprised to see that a ground medic was going on the flight to the hospital. Normally, the ground medic stays back. I explained to the medic the situation that had occurred earlier that evening. We both kept close watch on this soldier while we were en route to the Army hospital in Panama City. The helicopter had landed and my unit’s doctor greeted me. I explained to my doctor what had happened to the soldier and the actions that I took to save him. The patient was wheeled to the emergency room and then admitted to the intensive care unit. In the intensive care unit, his breathing status and heart status could be continuously monitored. It was more than I could have done for him on the ground. It turns out that when he passed out and went under in the swamps, he aspirated some of the swamp water. He was treated for several days and released. We made sure not to let him go out to the field for the rest of that training mission. I was happy; I had a chance to save one of my own people, even during a training exercise.

Most of my time in the 160th was spent staying at Hunter Army Airfield, Georgia, where we were based, going on temporary duty somewhere, or going to school to train. We had both specially modified Blackhawk and Chinook helicopters. Almost every time members of the battalion would go somewhere, a medic had to go along, so someone from our medical section was always away. Rarely did we travel as an entire unit. The one time we did was when we went to Camp Shelby, Mississippi. We drove in our military vehicles from our base to the camp in March, 1993. We were conducting training operations, doing the same thing that we did back at our base in Georgia.

Camp Shelby is a Reserve Army base that has excellent training facilities. We lived in open bay barracks for this two-week training mission. Our section’s job was the same – to provide medical support to the battalion. We crammed as much army training as we could into those two weeks. One day we parachuted out of the Chinook helicopters; the next day we went to the range to shoot our weapons. We did physical training every morning like we did back in Georgia. We tried to have a compass course one time, but we had a massive freak snow storm, and it was not worth the risk having our soldiers get hurt or injured in the snow. Once the weather cleared up, we went on a land navigation course. Anytime anyone got hurt or injured beyond what I was comfortable seeing, I would take them to the local emergency room off base.

The first time I met soldiers from the Army National Guard was in May, 1993. The 245th Aviation out of Oklahoma had a Special Operations Aviation unit associated with the 160th SOAR. They went to Fort Polk, Louisiana, to fly around with my battalion and to do their two-week annual training exercise. They didn’t have a medic with them, so I stayed in the same barracks as they did and assumed this role. I was ignorant and guilty of thinking that we were better than the National Guard. I was surprised to learn how dedicated these men were. From my perspective as a medic, they looked just like any of the active duty soldiers from my unit. Most of the enlisted soldiers had college degrees, and some even had master’s degrees.

My next training mission sent me to California, where I worked with the Downed Aircraft Recovery Team (DART). We stayed in the middle of the desert and trained every day. We were collocated with one of the Special Forces units. They were conducting border patrol activities and I worked with the medics on their teams when we went on a massive casualty exercise. I stayed on the ground to help with the wounded, but I was also the flight medic in the helicopter. Every few months I went to Fort Polk, Louisiana to provide medical support to members of my unit. All of the medics had to take turns going on different training missions. Fort Polk has a large training area and our unit would thus play the war games that were going on. One time the entire unit went to support training operations at Fort Polk, and a respiratory virus spread throughout the camp. We exhausted our supply of medical supplies in order to manage this.

One training mission that was significant to me was the last time I parachuted out of a plane. It was into Panama in December, 1994. We parachuted in and were going on patrol in the jungle. The jungle was hot, humid, and had a rotting smell to it. The flora was thick and had a multitude of colors. As the sun came up so did the temperature. They say the closer you are to the equator, the hotter it gets. This is the case in Panama. I stayed drenched in sweat all the time, which actually helped to cool me off. Once my body got used to being wet, the uneasiness of that sensation subsided.

We patrolled up and down small hills. In any other environment, this would not be a big deal, but dealing with the heat, humidity, and the dense jungle made our patrol very slow. It would only take a few minutes in a car to get to where the post was; on foot in the jungle it could take a few days. We covered only 3 kilometers after patrolling for eight hours. My heart pounded as I walked up those small hills; I was expecting relief on the way down, but my heart pounded just as fast and hard. The ground was muddy and my boots would get stuck in the mud if I stayed in one spot too long. I had to watch my footing, especially when going down a hill; I did not want to slip, not in the jungle. After a good day of patrolling, we found dry ground to sleep on for the night. Everyone had to take turns pulling guard duty though, not because we were afraid of being attacked by the enemy or anything, but because of the animals in the area. A group of monkeys did not appreciate it when we decided to sleep in their area one night and they screamed and threw rocks and their own feces at us. Those were some funny monkeys! I really didn’t care because I was totally exhausted. I pulled my poncho liner out of my rucksack, spread it over the ground and used my medic bag as a pillow to sleep. I sprayed on insect repellent and I crashed for the night, until it was my turn to stand guard. After patrolling for several days, we marched back to the fort and enjoyed our time in this tropical paradise.

My last mission with the 160th SOAR was onboard the USS Theodore Roosevelt. I had never been aboard a Navy ship before, so this was something new for me. Our unit was using this aircraft carrier as a base to fly in and pick up Special Forces and Navy SEAL teams. These forces were dropped off into different training areas along the coast. I went up with our Blackhawk helicopters; it was good to get off that ship for a few hours as I was getting seasick.

I went on so many training missions with the 160th. I traveled to Korea, Canada, Fort Campbell, Fort Bragg, California, Florida, and I even provided medical support as members of the unit walked the Appalachian Trail. I enjoyed my time with the 160th SOAR. I joined the unit as a wet-behind-the-ears medic. I went to war with the unit and served my time honorably with them. I left the unit as a seasoned combat medic. When I left the Army, I went back to college to train as a registered nurse. I was out for almost a year and I missed the Army. I wanted to be green, to be a soldier again, but only on a part-time basis. I swore into the Kentucky Army National Guard at Fort Knox. I was assigned to the Charlie Company, 103rd Support Battalion, which belonged to the 149th Mechanized Infantry Brigade. The unit was a part of the 35th Infantry Division.

A traditional soldier in the Army National Guard is a part-time soldier. Typically the soldier trains with the unit once a month and for two weeks in the summertime. The Army Reserve is another part-time branch of the Army, but typically Reserve units have training and support missions and not direct action missions. That does not mean that Reserve soldiers don’t go into combat; it’s just how the different branches are organized. My first drill with my Guard unit consisted of going to the field overnight at Fort Knox. I was in a medical company and assigned to the treatment platoon. We rode in tracked vehicles that weekend. One of the sergeants in the unit gave me a quick crash course on how to drive these vehicles. We drove around the woods just having a good time. I went to Ecuador with the National Guard in 1996 in a medical training exchange exercise. I was tasked to teach a class on controlling bleeding. I had insight on this because of my combat experience, and I learned some tricks of the trade from some of the Ecuadorian medics. We ate and slept in the same barracks as our fellow Ecuadorian medics did. These soldiers liked to cut-up just like American soldiers.

The next unit I belonged to was the 76th Infantry Brigade out of Indianapolis, Indiana. I joined Charlie Company, 113th Support Battalion. Again, I belonged to a medical company. The unit was relatively new and we had pretty decent equipment. The whole brigade was going to Fort Polk, Louisiana, in 2000, so the annual training in 1999 was geared toward preparing for this mission. We set up our tents out in the field. We had an ambulance platoon and a treatment platoon that the medics belonged to. They assigned me to work in the patient holding area because I was a registered nurse. I wasn’t too keen to work inside a tent, but I went along. It was a big deal for an Army National Guard Infantry Brigade to go to the Fort Polk training center – it was one of the best training sites in the world. We were inside the training area, otherwise known as the “box.” I spent the entire time working inside my patient holding tent, and I didn’t enjoy it at all. It was just like working in a hospital medical floor, but without the hospital. Some of the medics went on missions in the treatment platoon, setting up their treatment sections in direct support of the infantry units, but I was stuck in the silly tent. The only way I could get out of this deal was to get out of the military entirely. I finished my obligation with the Guard and took a few months off to relax. I had plans to rejoin the Guard – I just needed a break. I wanted to go to an infantry unit somewhere as a medic, but the only opening was with Headquarters Company, 76th Infantry Brigade. It was better than being in a medical company stuck in a patient holding tent.

I joined the unit in August, 2001, less than a month before the 9/11 attacks. At some point, I knew I would go to war again. After the attacks, National Guard soldiers took what we did on drill weekends more seriously. We prepared ourselves for combat because we knew we would all be called up eventually. I deployed to Afghanistan in 2004 with the 76th Infantry Brigade for one year. When we came home, everything seemed different. I didn’t feel like staying in the same unit any longer. The death of four members of my unit during the war was the main reason. I felt like I was stagnant having stayed with the same unit for such a long time. I wanted to experience a different type of unit. I transferred to the 138th Field Artillery Brigade out of Lexington, Kentucky. It was here I finished my 20 years in the military. The unit sent field artillery soldiers to Iraq and Afghanistan, but they did not do field artillery work. Many of the soldiers did jobs typically associated with the infantry. I hate it when active duty soldiers think of themselves as being better soldiers than Army National Guard soldiers. I was guilty of doing this myself until I met some National Guard soldiers and listened to their stories. Whether in the Guard or on active duty, a soldier is a soldier.

EIGHTY SECOND

Eighty-second Patch on my shoulder,

Pick up your chutes and jump with me I am the Infantry

One-oh-one Patch on my shoulder,

Pick up your weapons and follow me I am the Infantry

First Division Big Red One

Pick up your weapons and follow me I am the Infantry

Airborne Medic Cross on my shoulder,

Pick up your Aid Bag and follow me I am the Infantry

A MH-60 Blackhawk from the 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment. These are highly modified helicopters that perform special purpose missions. This photo was taken during Desert Storm in 1991.

Flying past the burning oil wells into Kuwait during Desert Storm in 1991.

Posing next to the MH-60 Blackhawk at Fort Sherman, Panama, in December 2004 before a training mission.

A patient in the back of the ambulance getting much-needed IV fluids during a training mission.

Inside of an Afghanistan National Army Hospital medical surgical ward.

An ambulance parked next to the medic aid station during a winter storm in Herat, Afghanistan.

Outside the Afghanistan Medical Aid Station. Both the Red Cross and crescent moon are symbols of medical care and non-combatants.

The combat medic repacking his medical bag after each and every mission.

Getting a chance to meet President Karzai when he came to visit in Herat, Afghanistan.

Discussing issues with the Afghan doctor that we were embedded with in Herat, Afghanistan.

Having fun with a soldier medic snowman we made.

Working with some Afghan combat medics in our medic aid station.

Captured enemy weapons depot in Herat, Afghanistan that will soon be exploded and destroyed.

Mortar infantry soldiers launching rounds in Herat, Afghanistan.

Inside our medic aid station with the medical chests.

Inside an Afghan pharmacy.

A young boy from Shindand, Afghanistan, where two warlords were fighting. This image was taken at a gas station where we set up an infantry checkpoint while embedded with the Afghan National Army. I treated the boy for an eye infection.

Afghan Army soldier getting needed IV fluids for acute sickness. The soldier is resting at the Afghan medical aid station.

Surgical operating room at a hospital in Shindand. The hospital was built by the Russians when they invaded Afghanistan in 1979 and is now run by local medical personnel.

Morphine auto injectors that are given for pain during combat. Each gives 10mg of morphine that is injected into the muscle. The injectors are used only once.

A CCP, or casualty collection point, where the wounded are collected after an attack. Litter teams will bring wounded to the collection point where the medics work on them.

IV training for combat infantry forces. I conducted a Combat Lifesaver Course during my deployment in Afghanistan. It is important for the infantry forces to have some basic lifesaving skills in case they go on a patrol without a medic or if the medic is injured.

Wishing an Afghan National Army soldier well on board a C-130 cargo plane. The picture was taken during combat operations in Shindand, Afghanistan. We had to tie the patient to the floor of the plane. We wrapped kerlex around the patient and the green Army blankets to secure the patient to the litter. Kerlex is a long roll of gauze that can be used as a dressing.

Taking care of a young Afghan girl in the back of the ambulance on the way to the Afghan hospital.

Mercedes Benz car made into an ambulance by the Afghan Army.

Inside the Italian trauma station in Herat, Afghanistan.

Posing in back of an Italian ambulance with one of the Italian doctors in Herat, Afghanistan.

The hand of a soldier who suffered from severe frostbite in Afghanistan.

Posing in front of the ambulance after a medical evacuation. We used the C-130 cargo plane for our medical evacuations.

The Five Pillars in Herat, Afghanistan.

Preparing to receive wounded outside the makeshift trauma station in Shindand, Afghanistan.

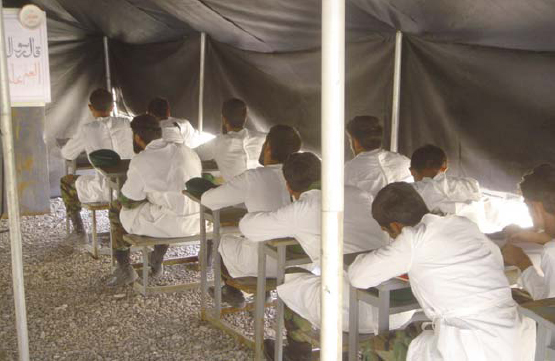

Afghan Army medics training in a classroom setting to become better medics.

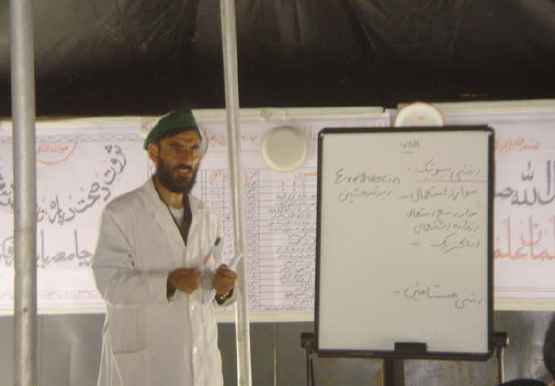

Afghan doctor training his medics in a classroom setting.

Afghan Army medics from Herat, Afghanistan, posing for the camera.

Memorial of four soldiers from Task Force Phoenix who belonged to 76th Infantry Brigade, Indiana Army National Guard.