This chapter will show you how the computer-adaptive sections of the GMAT really work. You will learn to pace yourself and to take advantage of the test’s limitations.

To understand how to beat the computer-adaptive sections (Math and Verbal) of the GMAT, you have to understand how they work.

Unlike paper-and-pencil standardized tests that begin with an easy question and then get progressively tougher, the computer-adaptive sections always begin by giving you a medium question. If you get it correct, the computer gives you a slightly harder question. If you get it wrong, the computer gives you a slightly easier question, and so on. The idea is that the computer will zero in on your exact level of ability very quickly, which allows you to answer fewer questions overall and allows the computer to make a more finely honed assessment of your abilities.

During the test itself, your screen will display the question you’re currently working on, with little circles next to the five answer choices. To answer the question, you use your mouse to click on the circle next to the answer choice you think is correct. Then you press a button at the bottom of the screen to verify that this is the answer you want to pick.

What you will never see is the process by which the computer keeps track of your progress. When you start each adaptive section, the computer assumes that your score is average. So, your starting score for each section is around a 30. As you go through the test, the computer will keep revising its assessment of your score based on your responses.

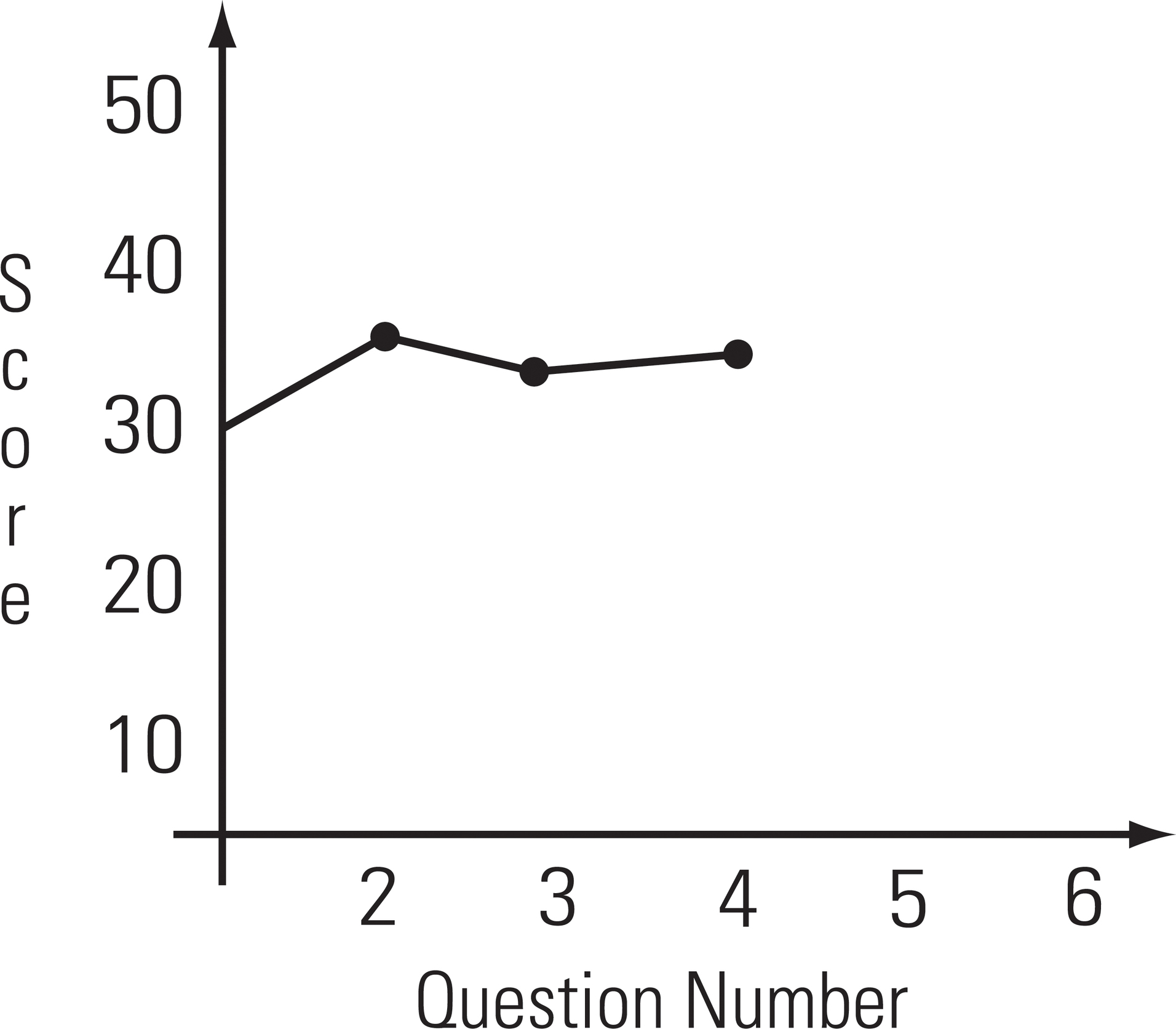

Let’s watch the process in action. In the left-hand column on the next page, you’ll see what a hypothetical test taker—let’s call her Jane—sees on her screen as she takes the test. In the right-hand column, we’ll show you how GMAC keeps track of how she’s doing. (We’ve simplified this example a bit in the interest of clarity.)

Note: The answer choices on the actual GMAT don’t have letters assigned to them. Instead, you select your response by clicking on an adjacent oval. For the sake of clarity and brevity, we’ll refer to the five answer choices as (A), (B), (C), (D), and (E).

To regard the overwhelming beauty of the Mojave Desert is understanding the great forces of nature that shape our planet.

understanding the great forces of

understanding the great forces of

to understand the great forces to

to understand the great forces to

to understand the great forces of

to understand the great forces of

understanding the greatest forces in

understanding the greatest forces in

understanding the greater forces on

understanding the greater forces on

When you start each adaptive section, the computer assumes that your score is average. So, your starting score for each section is around a 30. Jane gets the first question correct, (C), so her score goes up to a 35, and the computer selects a harder problem for her second question.

Hawks in a certain region depend heavily for their diet on a particular variety of field mouse. The killing of field mice by farmers will seriously endanger the survival of hawks in this region.

Which of the following, if true, casts the most doubt on the conclusion drawn above?

The number of mice killed by farmers has increased in recent years.

The number of mice killed by farmers has increased in recent years.

Farmers kill many other types of pests besides field mice without any adverse effect on hawks.

Farmers kill many other types of pests besides field mice without any adverse effect on hawks.

Hawks have been found in other areas besides this region.

Hawks have been found in other areas besides this region.

Killing field mice leaves more food for the remaining mice, who have larger broods the following season.

Killing field mice leaves more food for the remaining mice, who have larger broods the following season.

Hawks are also endangered because of pollution and deforestation.

Hawks are also endangered because of pollution and deforestation.

The computer happens to select a Critical Reasoning problem.

Oops. Jane gets the second question wrong (the correct answer is (D)), so her score goes down to a 32, and the computer gives her a slightly easier problem.

current score: 32

Nuclear weapons being invented, there was wide expectation in the scientific community that all war would end.

Nuclear weapons being invented, there was wide expectation in the scientific community that

Nuclear weapons being invented, there was wide expectation in the scientific community that

When nuclear weapons were invented, expectation was that

When nuclear weapons were invented, expectation was that

As nuclear weapons were invented, there was wide expectation that

As nuclear weapons were invented, there was wide expectation that

Insofar as nuclear weapons were invented, it was widely expected

Insofar as nuclear weapons were invented, it was widely expected

With the invention of nuclear weapons, there was wide expectation that

With the invention of nuclear weapons, there was wide expectation that

Jane has no idea what the correct answer is on this third question, but she guesses (E) and gets it correct. Her score goes up to a 33.

You get the idea. At the very beginning of the section, your score moves up or down in larger increments than it does at the end, when GMAC believes it is merely refining whether you deserve, say, a 42 or a 43. The questions you will see on your test come from a huge pool of questions held in the computer in what the test writers call “difficulty bins”—each bin with a different level of difficulty.

Unfortunately, approximately one-fourth of the questions in each adaptive section (Math and Verbal) won’t actually count toward your score; they are experimental questions being tested out on you. The difficulty of an experimental question does not depend on your answer to the previous question. You could get a question correct and then immediately see a fairly easy experimental question.

So, if you are answering mostly upper-medium questions and suddenly see a question that seems too easy, there are two possibilities: a) you are about to fall for a trap, or b) it’s an experimental question and really is easy. That means it can be very difficult for you to judge how you are doing on the section. Your best strategy is to simply try your best on every question.

Remembering that experimental questions are included throughout the adaptive sections can also help you use your time wisely. When you get stuck on a question—even one of the first ten questions—remember that it might be experimental. Spending an inordinate amount of time on one question could cause you to rush and make silly mistakes later. Would you really want to do that if the question turned out to be experimental?

In those situations, eliminate as many answer choices as you can, guess, and move on to the next question.

The GMAT keeps a running tally of your score as it goes, based on the number of questions you get correct and their levels of difficulty—but there are two other important factors that can affect your score:

Early questions count more than later questions.

Questions you leave unanswered will lower your score.

At the beginning of the test, your score moves up or down in larger increments as the computer hones in on what will turn out to be your ultimate score. If you make a mistake early on, the computer will choose a much easier question, and it will take you a while to work back to where you started from. Similarly, if you get an early problem correct, the computer will then give you a much harder question.

However, later in the test, a mistake is less costly—because the computer has decided your general place in the scoring ranks and is merely refining your exact score.

While it is not impossible to come back from behind, you can see that it is particularly important that you do well at the beginning of the test. Answering just a few questions correctly at the beginning will propel your interim score quite high.

Make sure that you get these early questions correct by starting slowly, checking your work on early problems, and then gradually picking up the pace so that you finish all the problems in the section.

Still, if you are running out of time at the end, it makes sense to spend a few moments guessing intelligently on the remaining questions using Process of Elimination (POE) rather than random guesses or (let’s hope it never comes to this) not answering at all. You will be pleased to know that it is possible to guess on several questions at the end and still end up with a 700.

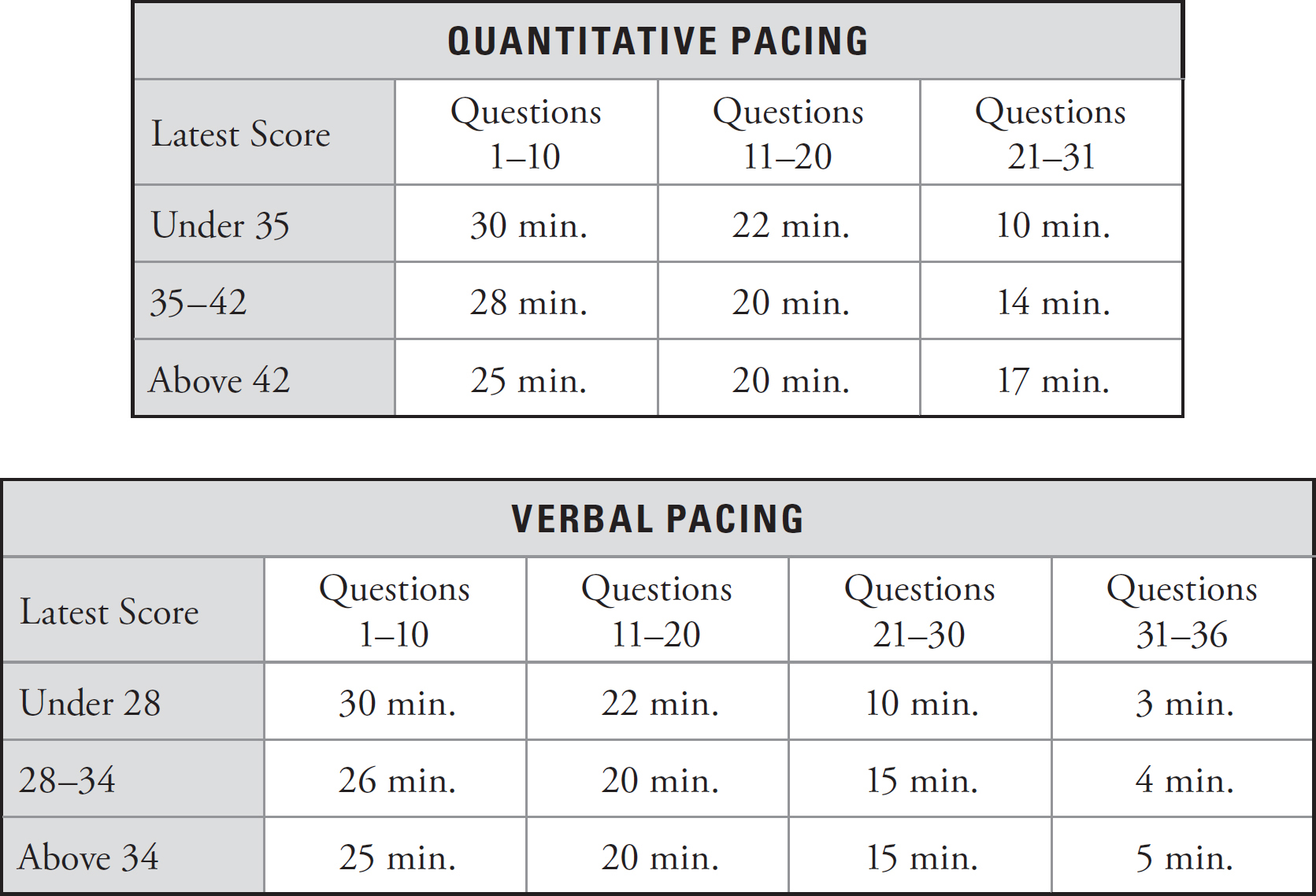

On the next page, you’ll find our pacing advice for Math and Verbal. The charts will tell you how much time you should spend for each block of ten questions based on a practice test score.

To help you ace the computer-adaptive sections of the GMAT, this book is going to provide you with

test-taking techniques that have made The Princeton Review famous and that will enable you to turn the inherent weaknesses of the computer-adaptive sections of the GMAT to your advantage

a thorough review of all the major topics covered on the GMAT

a short practice test to help you predict your current scoring level

practice questions to help you raise your scoring level

According to classic theory, the average test taker spends most of his or her time answering questions at his level of competency (which he gets correct) and questions that are just above his level of competency (which he gets wrong). In other words, most test takers will see questions from only a few difficulty “bins.”

This means that to raise your score, you must learn to answer questions from the bins immediately above your current scoring level. At the back of this book, you will find a short diagnostic test to determine your current scoring level and then bins filled with questions at various scoring levels. When combined with a thorough review of the topics covered on the GMAT, this should put you well on your way to the score you’re looking for.

But first, let’s learn with some test-taking strategies.

The computer-adaptive sections of the GMAT always start you off with a medium question. If you get it correct, you get a harder question; if you get it wrong, you get an easier question. The test assigns you a score after each answer and quickly (in theory) hones in on your level of ability.

Mixed in with the questions that count toward your score will be experimental questions that do not count toward your score. The testing company is using you as an unpaid guinea pig to try out new questions. Approximately one-fourth of the questions in each of the adaptive sections are experimental.

Because the test is taken on a computer, you must answer each question to get to the next question—you can’t skip a question or come back to it later.

Because of the scoring algorithms, early questions count more than later questions—so check your work carefully at the beginning of the test.

The GMAT computer-adaptive sections select questions for you from “bins” of questions at different levels of ability. The Princeton Review method consists of finding your current bin level through diagnostic tests and then practicing questions from that bin, gradually moving to higher bins as you become more proficient.