Problems as Opportunities

The ratio was telling.1 Just one safety check to two camera checks. It was spring 2016, and Franky Zapata was about to try a four-minute trip on the flying hoverboard he had built. It would dart thousands of feet above the ground at fifty-five kilometers per hour. Four engines, each with 250 horsepower, would give him flight, and Zapata wanted to be sure the cameras were ready. His team at Zapata Racing would later post the video to YouTube. They’d better get some good footage.

Beyond that, Zapata, a former champion Jet Ski racer turned entrepreneur, had not much of a plan. “You know when you decide to have a child, you decide to have a child because you want it. You don’t decide to have a child because it will become a surgeon or a lawyer,” he later explained by way of analogy to a reporter.2

It’s possible Zapata’s “child” was about to follow a decidedly different career path. A commander within one of the classified programs at the US Special Operations Command saw the clip on YouTube not long after. He forwarded it to James Geurts and Tambrein Bates along with the text, “Why aren’t we doing this?”

Geurts was in charge of equipping, training, and supplying the nation’s most elite warfighters: the Navy SEALs, the Army Special Forces, the Air Force Air Commandos. Bates was a former special operator himself. He had been deployed all over the globe: Somalia, South America, the Balkans, Afghanistan, and Iraq.3 He ran an outpost of the Special Operations Command, called SOFWERX, that Geurts had set up (in a former tattoo parlor) to be best in class “in the future.” And the two now found themselves intrigued by a 121-second video of a French thrill seeker on his flying board.

Geurts wasn’t sure the flyboard was real. Bates found the music kind of “campy,” but he cold-called Zapata Racing anyway. “I told them who we were and said I would love him to come talk to us . . . If it’s real, let’s see what you can do with it.”

And with that, Zapata flew to Florida to meet with Geurts, Bates, other SOFWERX affiliates, and special operators—though without his flyboard, because it couldn’t get through French export restrictions. Reporters had wondered whether the flyboard was “the coolest thing ever invented” or “a massive hoax.”4 Geurts and crew were about to find out.

After Geurts tipped me off to the video and I learned of his sincere interest in it, I wanted to uncover something else: Why?

Why were Geurts and Bates and the commander who had sent them the link trolling for ideas on YouTube? The US Department of Defense spends more than $600 billion a year.5 It employs more people than any other organization in the United States. Among them are the country’s bravest and most ingenious. The Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), the DoD’s research arm, is one of the most renowned in the world. Scientists there helped invent the internet, developed GPS, and built the ancestor to cloud computing.6 On top of that, American defense firms spend billions on research and development every single year to invent new solutions to the nation’s security challenges. So why was Geurts mining ideas for the most elite warfighters, who get sent on the most dangerous missions, in the same place you and I watch prank videos and clips of Colbert?

In chapter 2, we’ll address more directly the virtues of looking for ideas among so-called nonexperts. But I wanted to be sure as I took my own trip to Tampa that we really had to go looking for them at all. When I think of most of the public problems we face—from poor nutrition to low literacy rates to crumbling roads—the argument that “we know what to do, we just have to get people to agree to do it” sounds pretty darn compelling. Too little commitment. Too much politicking. Too much partisanship. Too much red tape. Those are the reasons, we’re told, why we don’t solve big problems anymore. It can’t really be from a lack of creativity, can it?

SOFWERX

With a few exceptions, the SOFWERX offices looked like every other startuppy “this is where new ideas are made” space I’d ever been in. It had the requisite open floor plan. Plenty of bricks, exposed beams, and cement. The cool swag. The digital monitors. Groups of young people, and some not-so-young ones, tinkered away. When I walked in, the only thing that stuck out—other than the fact that I’d just wandered into an outgrowth of the US Special Operations Command with a colleague and there were no military police, not even a gate, to stop us—was the fitness room. It was more metal plates than Peloton. Geurts had said he wanted to create a “mosh pit.” The office looked to me like Google’s, but with power drills and 3D-printed explosives.

Not on the day we were there, but on many other ones, SOFWERX hosted a wide variety of activities to give life to Geurts’s pit. There were rapid-prototyping events and “collaboration and collision” events, which Geurts liked to call “rodeos.” At ThunderDrone, in 2017, the team had invited companies to demonstrate their drone technologies (officially, “unmanned aerial systems”), with a special focus of getting the drones to work together in swarms. A Game of Drones was scheduled for the next year, where top performers would compete for cash prizes. Earlier, SOFWERX had organized something called a Pirates Exercise, where the team worked to imagine how Special Operations Forces might be interrupted rescuing a captured tanker by the capturers using technologies they’d bought off the shelf. Spoofed GPS locations and jammed bulkhead doors were on the lists the team conjured up . . . and then published on the web. Pirates would be on Geurts’s mind when he saw Zapata flying for the first time7 (flying warfighters as counter-countermeasures to pirate countermeasures, perhaps).

The participants in these events were a motley crew. There were operators from many different Special Forces units. Government employees. Private entrepreneurs. College interns. High school students. I met some of University of South Florida’s young engineers working on shoebox-sized satellites that might capture battlefield intelligence. “People are bouncing in, people are bouncing out, some stay for a while, and some go,” Geurts explained. Clearly he hoped that this new generation would be among the some that stayed.

Geurts had conceived of what became SOFWERX three years before we walked in. He and a friend (a retired Air Force officer) had gone for burgers at a new restaurant in an old building in Tampa, Florida. Geurts left with an idea about how to “reinvent the way SOCOM invents.” What was wrong with the way Special Operations Command had been inventing?

Inventors from the Beginning

US special operators began as inventors. Forerunners to the Navy SEALs were the Naval Combat Demolition Units that were stood up during World War II. NCDUs raced into idea-making from the very start.8 Hitler’s army was relying on Belgian Gates along Omaha Beach and Utah Beach to thwart the Allies’ Normandy invasion. These German obstacles were “three tons of half-inch thick angle iron welded and bolted together into a ten foot wide by ten foot high barricade that would tear the bottom out of a landing craft at high tide and block them at low tide.” The trained warriors of the brand-new demolition units would have to figure out how to take down the gates, and in “such a way that they didn’t send shrapnel from the explosions whizzing around on a beach full of soldiers and demolitioneers.” More than fifty thousand troops would land at Omaha and Utah beaches, and the fate of the free world depended on inventing a means of getting through. So an NCDU Lieutenant, Carl Hagensen, did. He created a waterproof sack and filled it with C2 explosives, adding a cord and hook at each end of the sack so that it could be hooked to the gates and into other charges. He experimented with this “Hagensen Sack,” and then ten thousand of them were sewed and filled and used in the invasion. The NCDUs and Army combat engineers were able to blast open “five of the sixteen corridors assigned to them” and to create three more partial gaps, and “that was enough to allow the landings at Omaha beach and the Allied forces to pursue Hitler’s Army.”9

The special operators’ reputation for bravery was born on those beaches, and so was a legacy of ingenuity. It would continue via different units that also paved the way for the later SEALs, out in the Pacific Theater of the war. The Office of Strategic Services (OSS) Maritime Unit was known, “of all the forefathers of the SEAL teams . . . for pushing the limits of technology.” It adopted the first one-man submersible—calling it the “sleeping beauty”—used to propel an operator along the surface before submerging for an attack. It deployed the “floating mattress,” which could carry two people and was propelled by an electric drill drawing on a 12-volt battery. It hired Major Christian Lambertsen, who developed rebreathers in the 1940s for the Navy frogmen. The bubble-free diving apparatus initiated a new phase in underwater warfighting.10

From their inception these units attracted inventors, and that was still true—two generations later—as Geurts and his friend were brainstorming over burgers in Tampa. The special operators themselves were often inventing, and they had plenty of people inventing for them. The 2011 raid on Osama Bin Laden’s compound was aided by all manner of sophisticated technologies that had been developed for use by special operators, including drones that provided air support and stealth helicopters that ferried the operators into Pakistan. The team even included a military dog that had undergone sophisticated training to sniff out explosives and booby-trapped doors.11 In 2015, the Special Operations program under Geurts’s oversight forged ahead with a list of innovations that seemed to me like it had been swiped off of Tony Stark’s desk: low-cost/expendable satellites, advanced armor/materials, deployable rapid DNA analysis, unique night-vision devices, and even a Tactical Assault Light Operator Suit, a kind of armored warfighter exoskeleton nicknamed, yes, the “Iron Man suit.”12 So, what was wrong with the way SOCOM invented? Geurts and Bates were looking for ideas on YouTube, but Special Operations seemed, at least to my eye, chock-full of them.

New Ideas

“If we had a new idea around here, it would die of loneliness,” Mayor Menino used to tell us, and not happily. If he was right, I’d like to think we could be forgiven. Teams with people in their roles for a long time struggle to come up with new ideas. In government, people stay a while. We’ve learned since grade school the art of self-protection: We don’t want to look intrusive in our organizations, so we don’t offer ideas. We don’t want to look negative, so we don’t criticize the status quo.13 Rare is the organization designed to allow people to take the interpersonal risks of learning and sharing; these organizations do so by generating a sense of “psychological safety.”14 Public organizations conspire to provide not a lot of that. Moreover, even if we were brave enough to share new ideas, a kind of risk-aversion-induced unimagination takes hold (more on risk aversion in chapter 3). That is, if we won’t be allowed to try it anyway, why would we even bother to think it up? And on top of all this, an acute case of Not-Invented-Here Syndrome in government means that ideas from the outside, which might help generate new ideas on the inside, are rejected.15 In government, we even have our special idea frailties. Old bureaucracies get “ossified”; a buildup of programs leads to what one scholar has called “demosclerosis.”16 Furthermore if my mayor and others were expecting us to dream like Apple’s famed Steve Jobs, well, that was just expecting too much. We weren’t born Steve Jobs.

Some of these excuses would have withered under scrutiny if I had offered them to the boss. The truth is, you don’t have to be Steve Jobs to be entrepreneurial. There is scant evidence that entrepreneurs are born but not made. Entrepreneurship is a “what” and not mostly a “who.” You don’t have to be special. It can be learned and practiced, and designed into organizations, maybe even public ones. When Menino hectored us for new ideas, he wasn’t trying to get water out of a rock. He was trying to mold us into wells.

Opportunity Driven

In 1983, Howard Stevenson, a professor of entrepreneurship, described what that molding would take and foretold what was ailing—to the extent it was—Special Operations when I met Geurts. “Strengths have become weaknesses, and weaknesses strengths,” Stevenson noted while describing how resources wring the innovation out of us and how we might get it back.17

In the early 1980s, Stevenson set out to redefine entrepreneurship. Though the term had been defined many times over since being coined by French-Irish economist Richard Cantillon in the early eighteenth century, Stevenson found contemporary definitions wanting. He felt that by the 1980s the common understanding of entrepreneurship had come to rest too much on the notion of the entrepreneur as a risk-seeking, creative, brave (you can pick the adjective) individual.

In place of a “single model of the human being who is the entrepreneur,” Stevenson—later with colleague Bill Sahlman—laid out a range of six entrepreneurial behaviors.18 On one end of the range was the “trustee” and at the opposite end the “promoter.” In this conception, not all the way at the promoter end but close to it lie the entrepreneurs. Not because of some unique psychological makeup but because of the orientation they select along six different dimensions: Entrepreneurs in this formulation are driven more by the perception of opportunity than by the resources they have at hand. They commit to those opportunities often very quickly and for short time frames. They stage their commitment while maintaining minimal exposure throughout the process. They use resources only “episodically,” often renting (or the functional equivalent) instead of buying. They tend to organize with minimal hierarchy and avail themselves of informal networks. And they focus compensation toward value creation. “Trustees,” to an extreme, and “administrative managers,” in more moderation, take the opposite orientations along these six dimensions. They are strategically driven mostly by the resources they currently control. They take longer to commit to those opportunities and then stick with them for longer. They commit their resources for similarly long durations, often after a single decision up front. They own most of the required resources. They rely on more-formalized hierarchies. And they base compensation either on scope of responsibility or on meeting short-term targets.19

Entrepreneurs, Stevenson told us, are opportunity driven and not resource driven. He might as well have said “entrepreneurship is the opposite of what bureaucrats do,” and he and Sahlman said nearly that, but not pejoratively. Their focus, in fact, was more on private firms than on governmental organizations. Nonetheless, they identified the common features of many established organizations in which maintaining the status quo is what is tacitly and sometimes explicitly encouraged. Managers, responding rationally to what is encouraged (through compensation, promotion, etc.), happily oblige and steer clear of change. They described such managers as “classic bureaucrats,” not unlike public servants, who are trustees of public resources to which they’ve been . . . entrusted. What such managers can do best with what they have, the thinking goes, is what they should do.

Stevenson envisioned a spectrum of management, with administrative styles of leadership on the right and entrepreneurial styles on the left. Resources—yes, among other things, but especially the availability of resources—dragged managers to the right. Stevenson wanted organizations to find ways to pull their members back to the left, where, undistracted and unpressured by bounteous resources, they would be forced to look beyond, at what they should do, not just at what they could. Menino wanted to drag us there.

Creating Choices

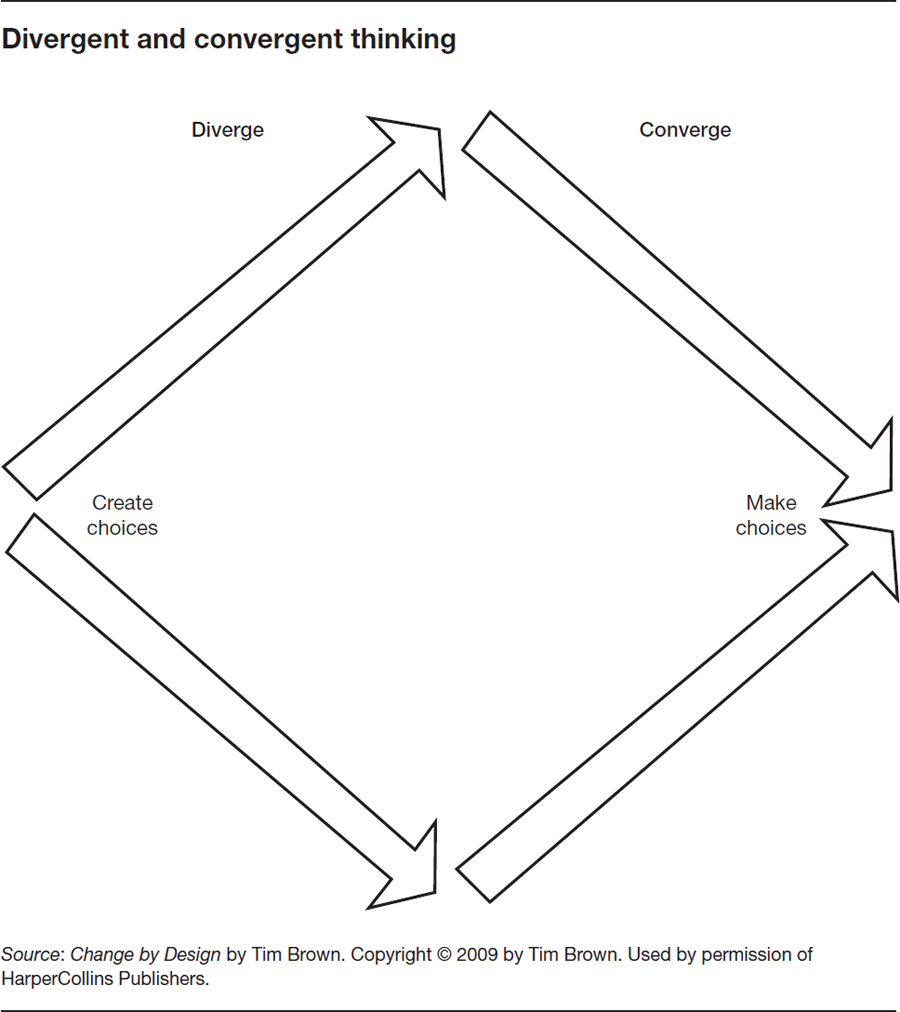

Design thinkers have a similar way of describing two alternate modes of thinking. Neither one is inherently better than the other, but one had come to dominate organizational thinking. Tim Brown, the CEO and president of IDEO, the innovation consultancy, described the difference between convergent thinking and divergent thinking, and the (great) need for both. “Convergent thinking is a practical way of deciding among existing alternatives,” he noted. It takes inputs and uses analysis and “drives us toward solutions.” Switching gears, he continued: “What convergent thinking is not so good at, however, is probing the future and creating new possibilities . . . The object of divergent thinking is to multiply options to create choices.” He quoted the two-time Nobel Prize–winning scientist Linus Pauling: “To have a good idea, you must first have lots of ideas.” He recognized the challenges of flooding organizations with more ideas but came out in favor of more ideas nonetheless, advocating a “dance” between the two approaches. “More choices means more complexity, which can make life difficult—especially for those whose job it is to control budgets and monitor timelines. The natural tendency of most companies is to constrain problems and restrict choices in favor of the obvious and the incremental. Though this tendency may be more efficient in the short run, in the long run it tends to make an organization conservative, inflexible, and vulnerable to game-changing ideas from outside.”20 Make choices, yes, but create them, too (see figure 1-1).

Geurts, in a similar vein, built SOFWERX to engineer a shift from a “scarcity” mindset to an “abundance” mindset. Scarcity is doing the best with what you have. Abundance is focusing on a problem and believing there are resources out there that can be brought to it, if you know how to marshal them. A scarcity mindset cuts ideas down before they even get thought up. An abundance mindset led Geurts to muse, “I want to create a giant bug light so people and ideas come to me.” Stevenson wrote, “The best administrative practices lead to immobility and to lack of ability to respond to opportunity. The best of administrative science has contributed to closed organizations.”21 Geurts believed that. He didn’t just want “new ideas.” He wanted a new orientation toward new ideas. Possibility and probability. Entrepreneurship and administration. Divergence and convergence. Abundance and scarcity. It’s a dance between the two, but in governments, we’ve forgotten half the steps. That’s why any new ideas are lonely.

That we’ve forgotten the steps is in some ways an outgrowth of our aging. It may not be political ossification per se—program on top of program, each with its own stakeholder—but it’s not not that. Asset on top of asset. Budget on top of budget. Resource on top of resource. Stevenson warned us it gets hard to do anything that’s not making the most of those. It gets hard to pursue any opportunity beyond them. Eighty years after the SEALs had been invented, by dint of all they’d invented, it’d gotten harder to do the same.

Best Isn’t Good Enough

There is a particular and much loved kind of administrative/convergent/scarcity thinking that appears so similar to its opposites that it’s hard to detect. But it is limiting our efforts at imagining new solutions to sticky problems and therefore our abilities to solve them. And that’s “best practices.” Too often in government, the search for a new solution begins and ends with a call for finding the best of what others are doing, and then doing that. I understand the appeal: replicate what works. And we should do that. We could lift up the lives of billions of people around the globe if solutions that had been developed and successfully implemented in some places made their way to all appropriate places. But we also must recognize that in many cases, best isn’t good enough. That “solutions” aren’t really solutions at all, but just the things that are being done. If you asked for best practices on what’s being done today to add affordable housing, reduce congestion, thwart climate change, narrow gaping inequalities, etc., you would get a list of very interesting and sometimes helpful practices. And if you, as a public leader, aren’t doing the things on that list, you should. And if you, the public, aren’t demanding them, you should. But the reality is, if you subjected the list to the test of “Will it be enough? Will it solve the problem?” the answer would likely be no. The best is only the best yet, so I think as possibilitists, we must beware best’s siren call.

Following the marathon attacks, the decision was made to cancel that night’s Boston Bruins hockey game, with a city in mourning and terrorists on the loose. Not long after that, Mayor Menino wanted to know if canceling had been my stupid idea, and I could honestly tell him it hadn’t been, because I hadn’t had an idea, stupid or otherwise, since those sobbing people had come streaming toward my home. (I think it was the right call, by the way, and I think eventually he did, too.)

An idea was forming in my head, though. And in his, and in a few others’. And the idea was that we needed to set up a brand-new fund to collect and distribute donations that were going to start coming in from around the world. The mayor was already taking the calls of people asking, “Where can we send help?”

The answer, in most US places affected by tragedy, was a local foundation. Best practices was to have an established, trusted organization collect donations and administer the funds. After the mass shootings in Columbine, Aurora, and Newtown, versions of this process had been put into practice in those locations. My mayor wasn’t inclined in that direction, however. He felt that when money went into foundations (which are the epitome of Stevenson’s “trustee”), it took too long to get out, and that when it ultimately did get out, it went in too many directions and not to those who most needed it. I agreed with that worry. I had, by pure chance, seen articles documenting some of the delays in disbursing funds to the Sandy Hook survivors. The shootings at Sandy Hook Elementary had happened 122 days before the marathon bombings, and still the major fund collecting donations hadn’t finalized a process for distributing those donations. In Columbine, it took years for donated funds to make it to victims, and even then they received only 58 percent of what had been collected. After Aurora, it took 259 days—almost a year—for the funds to make it to victims.22 The idea of best practices is beguiling, but it wasn’t going to be good enough. The mayor insisted, with the governor joining him, that we would start up our own new fund. “You can’t start something new,” we were told, a statement rooted in trusteeship that left unaddressed the matter of doing better. So, I had to tell the foundation head we were going to anyway.

The Age of Surprise

Geurts had seen reasons to think government had been pulled too far in one direction, but when he looked outside of government, he saw why it was actually urgent to pull us back. In fact, it was what was going on beyond Special Operations Forces (SOF) that had him most preoccupied. In a PowerPoint presentation he made around the time he was thinking up SOFWERX, he quoted former General Electric executive Jack Welch: “If the rate of change on the outside exceeds the rate of change on the inside, the end is near.”23 He was concerned about the “exponential environment” US Special Operators were facing. The missions, he said, were becoming more dynamic. Rapid change was everywhere. SOF had more partners, and therefore more integrations to navigate. It was getting harder to provide command and control in that environment. And while it was good that they could avail themselves of incredible new technologies in the private marketplace, these advancements too were increasing the complexity of the job. The competition was more agile, and he needed his organization—made up of seventy thousand people—to be as well. And leaving aside that his competition included stateless terrorists and nefarious states, he might have been talking about the challenges we all face in our own organizations. “We are living in the age of surprise,” Geurts said.

And then he laid out the challenge of living amidst surprise while trying to solve public problems. “People in government value being experts . . . their value is in what they know. The problem is, if the rules are changing, their value is waning.” It was a problem made worse by a creeping division in the United States, a widening civilian–military divide. “The population that understands the military has shrunk,” he pointed out. He looked ahead and thought, “As the percentage of the American public who were military-experienced or knew the military shrank, there would be an unhealthy trend where the military was revered but not understood.” There were more and more people who could help defend their country and its values, but didn’t know it or know how. Absent any change, it would be left to insider “experts,” but their expertise was concentrated in the past, and this fostered even more concentration. “Ducks pick ducks,” Geurts said, flagging the issue. “And if the world is changing, but you keep picking the same people based on the same expertise, that doesn’t work.”

There were other challenges, too. SOF units were the most frequently deployed forces in the post-9/11 era. They were busy. They were constantly fighting battles. And Geurts didn’t buy the conventional wisdom that being pushed to the brink would force innovation. “When you are in a crisis situation, our experience tends to be that you rely on what you know best,” he said. “You just try and hustle your way out of it. I don’t think you think any harder because you’re at war.”

Geurts dug into the US Special Operations Command archives to try to find out how you could think harder. He wanted to know how his predecessors at the OSS—the ones who had ushered in the “sleeping beauty” and the “floating mattress” and the rebreathers and so much more—had achieved so many innovations so quickly during a global war. “What I came to realize was that war forced these organizations to take opinions and get perspectives from a much more diverse set of folks. Either because all of your operators were forward in the field, so you had to bring in other, new people, or since you had a burning platform, other people who would not normally think to help the military, say fashion designers and painters who invented our modern camouflage, were now incentivized to help.”

What was wrong with the way SOCOM was inventing was that it was too busy with the here and now, too focused on what it knew and had seen already, and it had become too cordoned off from outside ideas. In SOFWERX, Geurts wanted a place where ducks and not ducks could come together and work together to solve the problems of the future. It strikes me now that when I watched the video of Zapata, I saw a flying hoverboard, whereas Geurts saw a not duck.

We Don’t Have to Be Special to Be Agile

I hadn’t thought about the flyboard for several months when, in the summer of 2019, it was all over YouTube again.24 High above the Champs Élysées, a man was flying on a board, participating in—headlining, really—France’s Bastille Day parade. After the video of the flying board circling the famed avenue below, followed by French fighter jets trailing smoke in the tricolors, came the millions of views, and then the fawning press, and the flabbergasted tweets—even a celebratory one from France’s president, Emmanuel Macron: Fier de notre armée, moderne et innovante.25 “Proud of our army, modern and innovative.” And why wouldn’t he be?

Except that it wasn’t a French soldier on Zapata’s flying board—it was Zapata. And the French hadn’t yet bought any of the boards for their use. (Zapata told me he thought they would be the first in the near future.) Truth was, neither had the Americans. No government had. Zapata said when I talked to him a few months after, “Soon it will be 2020, and the only solution right now to climb on a captured boat is to go up to it with your own boat and climb it with a vacuum system or magnets or even with a ladder. To me, it’s something from the pirates, something from 1,000 years ago. Nothing’s changed.”26 What’s so modern and innovative about that?

Geurts saw the whole thing as part of planning for the unplanned. He said they might buy some of the flyboards when they showed added military utility. His experiments with Zapata weren’t so much about whether the device would fly or not but about whether he could train soldiers that weren’t world-class athletes like Zapata, and how quickly. And he said, “I have fifty products like that. I don’t need them right now. But if I need them for something unexpected, I already have a relationship. Because of the networks we built, I could call Franky up at his house right now.”

He sounded, at SOFWERX, every bit the part of Stevenson’s entrepreneur. Driven by opportunity and not resources. Willing to act quickly, but sometimes shortly. Staging his investments, and ideally borrowing instead of buying the capacity he would need. And comfortable operating across relationships instead of up and down reporting lines.

By the time Zapata was back in the news, Geurts was in a new role. He had been nominated and then confirmed to be Assistant Secretary of the US Navy for Research, Development, and Acquisition. It was a post with a much larger reach. There were more than half a million people in the Navy, funded by more than $200 billion for the entire department, which operated “from the sea floor to space,” as Geurts liked to say. “You’ve been outspoken that you don’t have to have special in your name to be innovative and agile,” he remembers a very senior official telling him, working to recruit him to the role. During his confirmation hearings, Senator Elizabeth Warren said to him, “You’ve been the acquisition executive at Special Operations Command for a number of years, and I appreciate how you have prioritized agility and innovation in that role. But let’s face it. Special Operations is near the top in the flexibility that it is given when it comes to acquisition, and you are about to move to a military department that, mmm, does not have that same flexibility . . . so here is what I want to ask: How does your experience at SOCOM inform your outlook as a service acquisition executive?”27 Geurts called it “an excellent question” and went on to say that SOCOM had a sense of urgency, that it leveraged lots of different tools, and that it fostered a close connection between operators and the people who bought stuff for them, and that all three things were possible at the Navy, too. After being confirmed, he went and ran the SOCOM and SOFWERX innovation playbook, adapted for a department that built nuclear submarines and billion-dollar ships. He started something called NavalX to “take brilliant ideas,” ones that somehow wouldn’t have had a hearing or a champion, and push them forward. I paid particular note to a deputy director who said one of the goals was to allow people to get beyond “dated best practices.”28 Geurts was still, always, out looking for some novel solution to scary problems. He worried a lot about the so-called December 8th problem: How would the United States mass mobilize after an event of Pearl Harbor proportions? “If something big and unexpected happens, how will we react quickly? I am way into possibility now, because I don’t want to think about it when it happens.” And who did he invite to talk about it? A baker’s dozen of US CEOs, only two of whom were in defense. “Lots of people want to help, but they don’t know how to connect. And for me, the only cost was making the phone call.” He hosted other gatherings, larger in number (thirty or so) and diverse in their composition. One was on how to completely rethink the way the Navy upgraded computers and software on its ships. Another, on the anniversary of D-Day, was to consider how to create the same level of deception that had led to the success of D-Day, given modern circumstances. He calls them “possibility sessions.”

Beyond Resources Controlled

Again, Mayor Menino used to tell us that “if we had a new idea around here, it would die of loneliness.” But we had ideas every day. And we were supported by an ecosystem of ideas that stretched from community organizations in Boston to global networks. The United States alone has almost two thousand think tanks thinking.29 How could any of us in public life be short on ideas? How could any of ours be lonely?

Somewhere at a former tattoo parlor in Tampa, there was an answer, and it was this: On the whole, the ideas we have are a product of the resources we have at hand, and not of the problems in the world. They are sourced from the agencies we work in, limited by the funding we’ve been allocated, proscribed by the mandate we’ve been given. They are designed for a past that won’t return and a present that isn’t good enough. I heard Geurts say, “You don’t want an organization to be so fragile that you have to predict the future precisely.” But that’s what we’ve become in governments all around the world. Stiff from competence, if not complacency. And fragile to whatever is coming next.

But we aren’t too far gone. The pursuit of opportunity beyond resources controlled is an invitation to all of us, inside government and out, to imagine how we might help. We, the abundance.