24. WAIATA WHAKAORIORI

As sung by Tuara Adams of Ngaati Maniapoto tribe

Apirana Ngata and Pei Te Hurinui record that the composer of this song was Tuaarae, a high-born woman of the Waikato tribe. Tuaarae was originally married to a man of Waikato, but after quarrelling with him over a catch of rats which he had not shared with her, she left him for a chief of Ngaati Maniapoto in the Taumarunui district. When she later had a daughter, her husband’s other wives gossiped about her, saying that the child was a bastard. The husband heard of this and told them that the child was his own, but he offended Tuaarae by naming his daughter Hine-kiore, ‘Rat-girl’, in memory of the rats which had been the cause of Tuaarae’s leaving her first husband and marrying him. It was because of these insults that Tuaarae composed her song.

A genealogy published by Ngata and Te Hurinui shows six generations following Hine-kiore.

A different explanation as to the origin of the song is given in a manuscript written in 1864. According to this account, ‘a certain woman married a man, but they had no children. So the wife told her husband to adze a piece of wood. When he had done this he carved it, and it became their child. After a while the woman died, leaving it to her younger sister. Later the wood rotted, and the woman wept over that wooden child. Then she composed this song’. (McGregor 1893:53, Passage quoted in translation.) It is true that such figures were made and songs were composed for them, but this is an unlikely story.

The song is described by Ngata and Te Hurinui as a waiata whakaoriori. Musically it is a waiata rather than an oriori, and the term whakaoriori must refer to the fact that the composer has made use of literary conventions which are usually associated with the oriori. Both the formulaic opening line and the device of sending a child on an imaginary journey to visit relatives are very common in oriori; see for example Song 44.

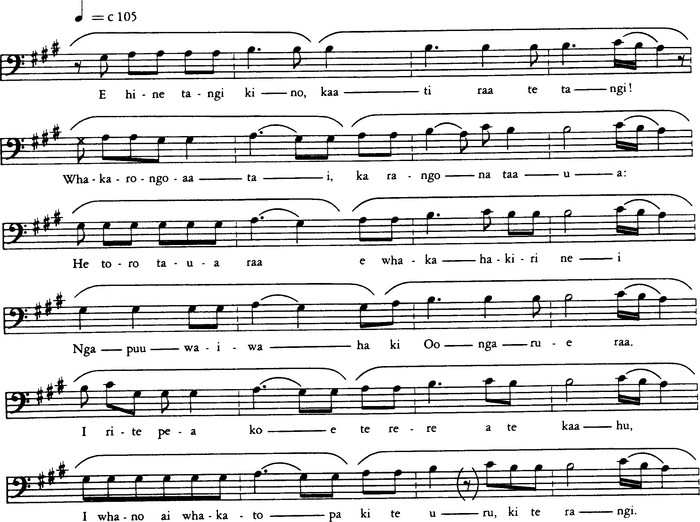

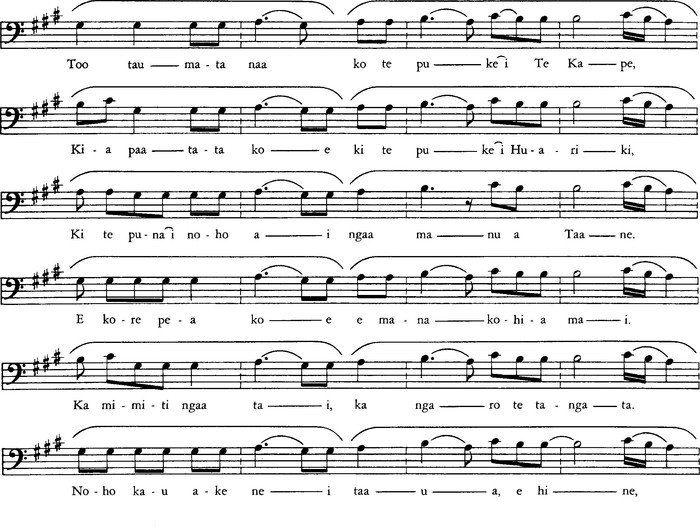

The melody sounds slightly Europeanised and is rhythmically almost  , with groupings of 6+7+7+7 = 27 quavers to each line emerging about half way through the song. A variant recorded by Kore Crown (McL 197) has a rather more elaborated melody, though with much the same overall pattern.

, with groupings of 6+7+7+7 = 27 quavers to each line emerging about half way through the song. A variant recorded by Kore Crown (McL 197) has a rather more elaborated melody, though with much the same overall pattern.

(Ref.: Ngata and Te Hurinui 1961:130-3).

WAIATA WHAKAORIORI

1 E hine tangi kino, kaati raa te tangi!

Whakarongo-aa-tai, ka rangona taaua:

He toro taua raa e whakahakiri nei

Ngaapuuwaiwaha ki Oongarue raa.

5 I rite pea koe te rere a te kaahu,

I whano ai whakatopa ki te uru, ki te rangi.

Too taumata naa ko te puke i Te Kape,

Kia paatata koe ki te puke i Huariki,

Ki te puna i noho ai ngaa manu a Taane.

10 E kore pea koe e manakohia mai.

Ka mimiti ngaa tai, ka ngaro te tangata.

Noho kau ake nei taaua, e hine,

Te puru ki Tuuhua, ki te ara o te riri.

Te menenga o te kai kei oo whaea raa:

15 Me whakahoro koe te horo o Houmea

Me i kore te hoomai teenei too ingoa,

Ko Wahine-ata koe. E moe i too moenga!

Kei pikipiki koe i te paepae tapu

I te kaha noo Tuu! Kauaka ia nei

20 E tupu whakataane! E taea e koe

Te peehi ngaa hau kia aropiri mai.

He mata te whakamau te pae ki Tautari;

Kei raro iti iho te whare i a Rangi,

Kia uhia koe ki te remu pakipaki.

25 He koro kia tutuki, kaati ka hoki mai ee!

WAIATA WHAKAORIORI

1 Daughter crying bitterly, stop your crying!

Listening as though to the sea, they will hear us —

The enemy quietly advancing

To Ngaapuuwaiwaha over at Oongarue.

5 If you could fly like a hawk

You would swiftly soar through the sky to the west,

Resting on the summit of Te Kape hill

Then on towards Huariki hill,

The source of the birds of Taane.

10 I do not think you will be welcomed there.

The tides ebb, and men are lost.

We are left here alone, daughter,

At the obstruction of Tuuhua, the paths of war.

Your aunts have much food:

15 Perform ‘the swallowing of Houmea’

If you are not given your name!

You are Wahine-ata. Sleep in your bed!

Do not mount the sacred threshold

Following the trail of Tuu! Do not

20 Grow up like a man! You will

Calm the winds and make them blow gently.

My eyes are fastened on the hills at Tautari.

Below them there lies Rangi’s home,

Where you will be clothed in a fine bordered cloak.

25 Our desires satisfied, we return ee!

NOTES

LINE

2 The translation of whakarongo-aa-tai is uncertain. The second part of the line may be understood as ka rangona [e] taaua, ‘they will be heard by us’.

4 Ngaapuuwaiwaha was a village in the Taumarunui district, near the junction of the Ongarue and Wanganui rivers.

6 The translation should perhaps be ‘You would swiftly soar up, entering the heavens’. But the text published by Ngata and Te Hurinui has ki te uru, ki te tonga, ‘to the west and to the south’.

7-9 The home of Tuaarae’s second husband was at Te Kape in the Taumarunui district. Huariki, a nearby hill, was an important place for snaring birds. Taane is the mythical personage associated with birds.

13 Tuuhua is a mountain about 11 miles north-east of Taumarunui. Among its foothills there were ancient war-trails leading in many directions. The proverbial expression ‘the obstruction of Tuuhua’ refers to the district’s strategic position.

14-17 The child’s ‘aunts’, her mother’s co-wives, had called her a bastard, and her father had given her an offensive name. In this passage they are threatened with witchcraft unless the girl is given her proper name of Wahine-ata.

Houmea is a mythical personage, a woman who swallowed up food and men (Orbell 1968:xiv-vii). A spell known as the tipi a Houmea was believed to have the power of destroying an enemy’s food supply, and te horo o Houmea, ‘the swallowing of Houmea’, must have been a similar spell employed for the same purpose.

18-19 Tuu is a mythical personage associated with warfare. Paepae tapu, ‘sacred threshold’, refers to the doorstep of a house.

22-24 Tuaarae belonged to the Waikato district but was now living in the Taumarunui district. Tautari, or Maungatautari, is a mountain on the south side of the Waikato river, near her former home. Rangi, or Rangihoto, was Tuaarae’s parent; see the genealogy published by Ngata and Te Hurinui (1961:130). Tuaarae tells her daughter that if she visits her grandparent, she will be received with honour.

24. WAIATA WHAKAORIORI